Abstract

Recent population-based studies indicate that sexual minorities aged 50 and older experience significantly higher rates of psychological distress than their heterosexual age-peers. The minority stress model has been useful in explaining disparately high rates of psychological distress among younger sexual minorities. The purpose of this study is to test a hypothesized structural relationship between two minority stressors—internalized heterosexism and concealment of sexual orientation—and consequent psychological distress among a sample of 2,349 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 to 95 years old. Structural equation modeling indicates that concealment has a nonsignificant direct effect on psychological distress but a significant indirect effect that is mediated through internalized heterosexism; the effect of concealment is itself concealed. This may explain divergent results regarding the role of concealment in psychological distress in other studies, and the implications will be discussed.

Keywords: Aging, bisexual, gay, lesbian, mental health, minority stress, older adults, psychological distress, sexual minorities

It is only recently that population studies have begun to examine lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) older adults as a group distinct from their older heterosexual counterparts or their younger LGB peers. Compared to their older heterosexual counterparts, LGB older adults have significantly higher rates of psychological distress (Wallace, Cochran, Durazo, & Ford, 2011), depression (Valanis et al., 2000), and poor mental health (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco, & Hoy-Ellis, 2013). LGB older adults also evidence lower rates of depressive symptomatology than their younger LGB peers (Cox, Vanden Berghe, Dewaele, & Vinke, 2009). Both older adults (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013) and LGB people (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011) are among targeted populations for the reduction of health disparities by Healthy People 2020. Accumulating research has documented disparate rates of psychological distress among LGB populations, yet before culturally appropriate interventions can be developed and implemented, underlying pathways that link risks to outcomes must be understood (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The purpose of this study is to identify one such underlying mechanism of risk for psychological distress among older LGB adults.

Depression is now considered a major public health issue (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, 2009). In addition to its toll on human wellbeing and more pragmatic economic costs, depression is significantly associated with higher rates of chronic disease, and it is projected to become a leading cause of worldwide disease burden by 2020, second only to heart disease (Chapman, Perry, & Strine, 2005). One of the specific objectives of the Healthy People 2020 initiative to reduce population health disparities and improve quality of life is to reduce the incidence of major depression (MHMD-4.2) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). In order to effectively intervene, understanding the correlates and etiology of depression (i.e., endogenous vs. exogenous) is crucial. One of the most widely measured correlates of undiagnosed depression is psychological distress (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), which has been associated with early onset of chronic illness, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and premature death (Russ et al., 2012).

The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) has been used increasingly in recent years to explain the disparately high rates of psychological distress among LGB populations (Herek & Garnets, 2007); it is also one of a handful of useful conceptual tools recommended for research studying LGB health disparities (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The primary assertion of the minority stress model is that although this “excess” psychological distress manifests at the individual level, it is rooted in societal heterosexism. Herek (2003) articulated heterosexism as “an ideological system that casts homosexuality as inferior to heterosexuality” (p. 158). From a cultural perspective, heterosexism stereotypes LGB people as deviant, abnormal, and unnatural. Cultural attitudes that privilege heterosexuality become enshrined in social institutions that through policies and practices marginalize and exclude LGB individuals. For example, employment discrimination based on sexual orientation is still legal in 29 states (Human Rights Campaign, 2014). It is important to recognize that heterosexism is not a static phenomenon, but one that has evolved over time. For example, from the early 20th century into the late 1960s, the dominant discourse of heterosexism was one that portrayed homosexuality as mental sickness and moral perversion, but as a consequence of the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and the ensuing modern gay rights movement, gay pride and liberation began to emerge as a counter-discourse to that of disease and criminality (Adam, 1987; Silverstein, 2009).

Minority stress model

The minority stress model articulates four minority stressors that are unique to LGB people’s sexual minority status; these stressors are additive, over and above general stressors experienced by most adults, such as involuntary unemployment or the loss of a close relationship, and they require additional adaptive responses (Meyer, 2003). The most distal of the stressors are actual experiences of discrimination and criminal victimization. More proximal to the individual are expectations of future experiences of discrimination and rejection, internalized heterosexism, and concealment of sexual orientation. Meyer (2003) also described community connectedness, being connected to LGB communities as a buffer against minority stressors. In this study, I focus on internalized heterosexism and concealment of sexual orientation as they relate to psychological distress among LGB adults aged 50 and older.

Internalized heterosexism

Through early and ongoing socialization processes (Brehm, Kassin, & Fein, 1999), prior to awareness of sexual orientation, which generally occurs in adolescence (Corliss, Cochran, Mays, Greenland, & Seeman, 2009; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001), members of a given society internalize and incorporate the constellation of attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes regarding heterosexuality and non-heterosexuals into their worldview, resulting in internalized heterosexism (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Szymanski, Kashubeck-West, & Meyer, 2008). Heterosexuals target these attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes toward LGB persons; LGB persons direct their internalized heterosexism inward toward the self, or outward toward other LGB persons (Herek et al., 2009). This unremitting application of negative regard toward the self is stressful (Meyer, 2003). Research has consistently found a significant positive association between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet et al., 2013; Frost & Meyer, 2009; Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011).

Concealment of minority identity

According to the minority stress model, concealing one’s sexual minority identity is both a protective factor and a source of stress. In the short term, concealment may be a protective factor, making the individual a less visible target for victimization and discrimination; over the long run, continuing to conceal that identity becomes stressful, ultimately “costing” the individual in terms of increased levels of psychological distress (Meyer, 2003). The model also postulates that disclosing one’s sexual minority identity (i.e., “coming out”) offers long-term “benefits” by reducing the levels of internalized heterosexism and consequent psychological distress. This benefit accrues in part through externalizing, to various degrees, internalized heterosexism. Individuals reevaluate and “normalize” their stigmatized identity by making more favorable comparisons of self with “like” others (i.e., other LGB persons), supplanting previous negative comparisons to heterosexuals. Through disclosure of sexual orientation and consequent normalizing via more positive comparisons of one’s marginalized sexual identity, the pernicious effects of early socialization related to internalized heterosexism may gradually diminish over the course of individuals’ lives (Meyer, 2003). Studies examining the relationship between concealment of sexual orientation and psychological distress have produced conflicting results. Concealment of LGB identities has been found to be a significant predictor of psychological distress by gender (Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011) and age (Rawls, 2004), yet other research has found no significant relationship between concealment and psychological distress (Balsam & Mohr, 2007). A similar nonsignificant relationship was found after controlling for age, income, and education (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim et al., 2013).

Rationale for current study

The age of 50 is a turning point for both physical and mental health. Many chronic conditions typically associated with older age begin to manifest around the age of 50, such as menopause (National Institute on Aging, 2010); 50 is also the age at which many recommended preventive screenings should begin, such as colorectal cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Psychological distress in the general population begins to decline around the age of 50 (Byers, Yaffe, Covinsky, Friedman, & Bruce, 2010), yet rates remain significantly higher among LGB adults aged 50 and older than those in the general population (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2011). At best, the underlying mechanisms of risk in psychological distress and depression among older LGB adults are only partially understood. In its original conceptualization, the “boxes” representing general, distal, and proximal minority stressors are portrayed as overlapping to denote their interdependency (cf. Meyer, 2003, p. 679). Furthermore, proximal minority stressors are placed in the same “box,” which obscures how each is structurally related to the others. However, the directional relationship between internalized heterosexism and concealment of sexual orientation (i.e., which “leads” to the other) is inferred through (Meyer, 2003) discussion of minority stress processes and related socialization processes. First, as previously noted, the internalization of heterosexism takes place early in life, prior to awareness of sexual orientation. Yet for LGB individuals, nascent awareness of sexual orientation leads to a recalibration of negative heterosexist attitudes, values, and beliefs toward the self, necessitating concealment of one’s non-heterosexual orientation, at least in the short term to protect the self from prospective harm. It is only in the long term that concealment becomes stressful and consequently contributes to psychological distress. Meyer (2003) posited that “internalized homophobia [i.e., heterosexism] signifies the failure of the coming out process to ward off stigma and thoroughly overcome negative self-perceptions and attitudes” (p. 682). In other words, from a theoretical perspective, disclosure of LGB identity leads to decreased levels of internalized heterosexism, which in turn is associated with lower levels of psychological distress. Thus I hypothesize that among older LGB adults, (1) concealment has a nonsignificant direct effect on psychological distress, and (2) concealment has a significant indirect effect on psychological distress that is at least partially mediated through internalized heterosexism.

Methods

Sampling and Recruitment

This study is a secondary data analysis of cross-sectional data from the Caring and Aging with Pride (CAP) project (N = 2,560). The university institutional review board (IRB) determined that this study and the secondary data utilized are exempt from human subjects review. The original CAP project was the first federally funded national study to examine the health and aging needs of sexual and gender minority older adults. The CAP project was a partnership between the Institute for Multigenerational Health at the University of Washington and 11 agencies across the nation serving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) older adults. These agencies were located primarily on the East and West Coasts and in the Midwest. In addition to full human subjects review by the hosting university’s IRB, several of the participating agencies conducted their own internal reviews. Paper and electronic survey packets, including standard project descriptions and informed consent materials, were distributed to potential participants via these agencies’ mailing lists and were returned between June and November 2010. To be included in the project, potential participants had to self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) and be 50 years old or older. In addition, respondents could choose to be entered into a raffle and selected for one of three $500 gift cards, regardless of whether the surveys they returned were completed or not. The response rate was 63%. For more complete information regarding the CAP project and methodology, see Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet, and colleagues (2013).

Participants

I excluded the 174 participants from the original CAP study who indicated that they were transgender, leaving a sample size of 2,349 self-identified non-transgender LGB adults aged 50 in this secondary analysis of CAP data. Although gender identity and sexual orientation are inextricably linked, they are nonetheless distinct constructs (Bao & Swaab, 2011; Diamond, 2002); the focus of this study is proximal minority stressors and psychological distress among self-identified LGB non-transgender older adults. The participants in the sample from the current study ranged in age from 50 to 95 years old (M = 66.9, SD = 9.0); 94.6% identified as lesbian or gay, and the remainder as bisexual. Slightly more than one third (35.4%) were women; 64.6% were men. Very few (7.7%) had only a high school education or less; the majority (92.3%) had at least some college education. Most (91.3%) identified as non-Hispanic White; the remaining 8.7% identified as Hispanic and/or non-White. Nearly one third (29.5%) had annual household incomes at or below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL); the remaining 70.5% had annual household incomes above 200% of the FPL.

Measures and Covariates

Internalized heterosexism was assessed by asking respondents to indicate their level of agreement on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree; 2 = agree; 3 = disagree; 4 = strongly disagree) to five statements adapted from Bruce (2006) that assessed internalized stigma related to sexual orientation. Example statements include: “I wish I weren’t lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender” and “I feel that being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender is a personal shortcoming for me.” Responses were then reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated higher levels of internalized heterosexism. Factor analyses indicated that all five items loaded well onto a single latent factor, with factor loadings ranging from .48–.79 (Cronbach’s α = .78).

Concealment was measured via a modified version of the Outness Inventory (OI) scale (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). The 12 items, covering three primary domains—family members, best friend, and community—ask participants whether specific people in these groupings were aware of their sexual orientation. Responses were coded on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = definitely do not know; 2 = probably do not know; 3 = probably know; 4 = definitely know), with lower scores indicating higher levels of concealment. Factor analyses indicated that all items loaded well onto a single latent factor, with factor loadings ranging from .63 to .91 (Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

Psychological distress was measured using the 10-item short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D 10 has valid and reliable psychometric properties (Zhang et al., 2012); Cronbach’s α = 0.88. The scale asks respondents to indicate how many days during the past week (0 = <1 day, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, 3 = 5–7 days) they had felt or behaved in certain ways. Examples include “I felt depressed,” and “I could not get going.” Possible scores ranged from 0–30, with scores of 10 or greater indicating clinically significant depressive symptomatology. Because of its previously established validity and reliability in capturing the latent variable psychological distress, the variable was treated as an observed indicator.

Age was determined by participants’ year of birth, which was dichotomized as 50 to 64 years old (coded 0) and 65 years old and older (coded 1). The demarcation of these age groups was based on the fortunate happenstance that CAP participants who were aged 50 to 64 years old when the original data were collected were members of the Baby Boom Generation (b. 1946–1964), while those aged 65 and older were members of the Greatest and Silent Generations (b. 1901–1945), who experienced very different social worlds when they were growing up and coming of age. This distinction is further supported by research that has documented a significant downward trend in psychological distress that begins around age 50, a trend that becomes even more pronounced beginning at age 65 (Byers et al., 2010).

Gender was determined by participants’ response to whether they considered themselves to be female (coded 1), male (coded 2), or other; those who endorsed other were excluded from this study.

Sexual orientation was assessed by respondents’ self-identification as lesbian, gay (coded 1), or bisexual (coded 0); those who indicated that they were heterosexual, straight, or other were not included.

Race/ethnicity was determined by participants’ response to whether they considered themselves to be White, Black or African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Other. They were also asked if they were Hispanic or Latino. For this study, race/ethnicity was dichotomized as non-Hispanic White (coded 1) and non-Hispanic other (coded 0) due to the small proportion of the sample who did not identify as non-Hispanic White.

Level of education was derived from the following categories with the highest level of education completed that respondents endorsed: 1st through 8th grade; 9th through 11th grade; completed high school, or obtained a GED; 1 to 3 years of college; or four or more years of college. In this study, education was dichotomized as ≤ high school or less (coded 1), or some college or more (coded 0).

Income was based on the household income category that was checked for the year the survey was completed. Income categories were less than $20,000; $20,000 to $24,999; $25,000 to $34,999; $35,000 to $49,999; $50,000 to $74,999; or $75,000 or more. Using this information, in addition to household size and calculation guidelines provided by the federal government (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009), income was dichotomized as ≤200% of the federal poverty level (FPL; coded 1) or >200% of the FPL (coded 0).

Procedure

Stata version 12 was used for all statistical analyses. Initial analyses provided descriptive statistics. I constructed a structural equation model (SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships between the latent variables concealment and internalized heterosexism and the observed variable psychological distress, controlling for the standard sociodemographic covariates of age, income, and education. Because significant differences in degrees of concealment by race/ethnicity (Moradi et al., 2010) and sexual orientation (Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt, 2009) and levels of internalized heterosexism by gender (Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011) have been noted, I also controlled for these.

SEM combines both factor analysis and multiple regression techniques, allowing for the use of both discrete and continuous observed indicators, such as items on a questionnaire as proxies for underlying latent variables, while accounting for measurement error. In addition, it also has the capability to decompose total effects into their direct and indirect components, which allows for interpretation of mediation effects (Duncan, 1975; StataCorp, 2011). Post-estimation tests provide insights as to how well the data fit the specified, a priori theoretical model; different tests examine different facets of goodness-of-fit (GOF) of the data to the model (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is considered to be among the most informative of model fit indices because it reports how well the sample parameters fit the population covariance matrix; RMSEA < .06 suggests a good fit. The comparative fit index (CFI) compares the sample covariance matrix to the null model, assuming uncorrelated latent variables. This statistic ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a good fit; CFI > .90 indicates that a misspecified model is not accepted as a “good” model. This index is least influenced by sample size. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) standardizes the square root difference of the residuals of the hypothetical population covariance matrix and the observed sample covariance matrix. These values also range from 0 to 1, unlike the CFI; values closer to 0 are indicative of good model fit. SRMR < .05 indicates a good model fit, although SRMR < .08 is considered acceptable.

I used the maximum likelihood (ML) method of estimation. Cases with missing data (n = 502) were excluded from analysis; inspection revealed that data were entirely at random. Both latent and measurement variables were skewed. However, with sufficiently large sample sizes (≥ 200), this is not an issue for SEM (Matsueda, 2012).

Results

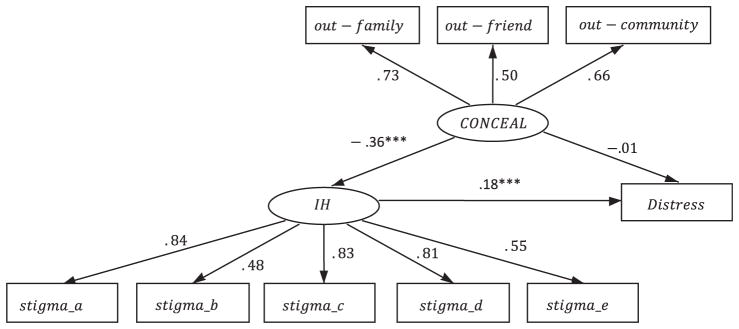

The path diagram for the structural equation model (SEM) is shown in Figure 1. Correlations of observed measures are shown in Table 1. Post-estimation goodness-of-fit (GOF) tests of Model 1 indicated a moderately good fit to the data. Post-estimation inspection of modification indices suggested correlated error terms in the indicators of internalized heterosexism and concealment; including these additional paths is theoretically sound, as the indicators were drawn from a single source (i.e., individuals’ self-reports) rather than from separate sources (e.g., self-reported income vs. income tax return (Bollen, 1989). Error-term correlations were included in Model 2; results indicated an even closer fit of the data to the model shown in Table 2. The coefficient of determination (CD) was 0.70, indicating that the variables in the model accounted for 70% of the variance in psychological distress. The total effect of concealment on psychological distress was significant (b★ =−.19, p = .027). Decomposition of total effects revealed that the direct effect of concealment on psychological distress was nonsignificant (b★ =−.01, p = .986), while the indirect effect through internalized heterosexism was significant (b★ = −.18, p < .001). To determine the proportion of the total effect that is mediated, the coefficient of the indirect effect is divided by the coefficient of the total effect (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). In this case, the indirect effect of concealment (−.18), divided by its total effect (−.19) = .947, indicates that nearly 95% of the effect of concealment on psychological distress is mediated by internalized heterosexism.

Figure 1.

Structural relationship of concealment, internalized heterosexism, and psychological distress. (This figure illustrates the structural relationship in the final model).

Note: Coefficients are standardized. CONCEAL = concealment of LGB identity; IH = internalized heterosexism; Distress = psychological distress. ***p < .001.

Table 1.

Correlations of latent variables and observed measures.

| Concealment (C)

|

Internalized heterosexism (IH)

|

CESD

|

Sociodemographics

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| 1 C—Friend | – | ||||||||||||||

| 2 C—Family | .36 | – | |||||||||||||

| 3 C—Community | .42 | .47 | – | ||||||||||||

| 4 IH Stigma—a | −.12 | −.19 | −.25 | – | |||||||||||

| 5 IH Stigma—b | −.05 | −.11 | −.09 | .39 | – | ||||||||||

| 6 IH Stigma—c | −.13 | −.18 | −.23 | .71 | .40 | – | |||||||||

| 7 IH Stigma—d | −.14 | −.18 | −.24 | .62 | .37 | .60 | – | ||||||||

| 8 IH Stigma—e | −.09 | −.13 | −.15 | .38 | .24 | .42 | .52 | – | |||||||

| 9 CESD (distress) | −.07 | −.04 | −.05 | .17 | .09 | .12 | .20 | .09 | – | ||||||

| 10 Age | −.09 | −.25 | −.12 | .06 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .03 | −.04 | – | |||||

| 11 Income | −.05 | −.05 | −.06 | .06 | −.02 | .02 | .09 | .03 | .24 | .09 | – | ||||

| 12 Education | −.10 | −.08 | −.06 | .04 | −.02 | .02 | .06 | .07 | .11 | .05 | .22 | – | |||

| 13 Gender | −.09 | −.12 | −.02 | .16 | .12 | .17 | .15 | .08 | .02 | .13 | −.01 | .05 | – | ||

| 14 Race/Ethnicity | .04 | −.03 | .04 | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | −.04 | −.02 | −.05 | .06 | −.10 | .00 | .01 | – | |

| 15 Sexual orientation | .02 | .10 | .13 | −.08 | −.06 | −.08 | −.04 | −.05 | −.02 | .01 | −.07 | −.01 | .06 | −.03 | – |

Table 2.

Post-estimation goodness-of-fit statistics.

| Statistic | Model 1 | df | p | Model 2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 208.62 | 25 | < .001 | 156.89 | 54 | < .001 |

| RMSEA | .06 | – | — | .03 | – | — |

| CI (90%) | [.05, .07] | – | — | [.03, .04] | – | — |

| CFI | .96 | – | — | .98 | – | — |

| SRMR | .03 | – | — | .02 | – | — |

Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine the nature of the structural relationship between internalized heterosexism, concealment, and psychological distress among LGB older adults. The results support the hypotheses that concealment has a nonsignificant direct effect on psychological distress among LGB older adults but does have a significant indirect effect that is nearly completely mediated through internalized heterosexism. Nearly all (95%) of the effect of concealment on psychological distress is mediated through internalized heterosexism. Because of nearly total mediation, the effect of concealment in psychological distress is itself concealed by internalized heterosexism.

The results of this study may also help explain disparate findings of other studies regarding the association between concealment and psychological distress. Balsam and Mohr (2007) found no significant association between psychological distress and concealment for LGB women or men, nor did Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet, and colleagues (2013), after controlling for age, income, and education. Both of these studies tested a direct effect of concealment and internalized heterosexism on psychological distress; both also found a significant relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress. If the effect of concealment is, in fact, fully mediated by internalized heterosexism, it would stand to reason that a significant relationship for concealment would not be detected. It is also important to note that the strength of the relationship between concealment and internalized heterosexism is twice that of the relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress.

Kuyper and Fokkema (2011) found that concealment is significantly associated with psychological wellbeing among LB women but not GB men. One possibility is that in this particular study, participants’ sexual orientation was assigned based on their response to a question about sexual attraction rather than self-identified sexual orientation; it is not clear whether the participants self-identified as LGB as in other studies. Sexual identity has been associated with psychological wellbeing among Flemish LB women but not GB men (Cox et al., 2009). It is possible that there are cultural differences between LB women and GB men in Europe and the United States, even though there are cultural similarities (Kuyper & Vanwesenbeeck, 2011). Kuyper and Fokkema (2011) also noted a significantly lower response rate than the CAP study (28% vs. 63%), which may indicate that the respective samples differ in important ways, at least one of which is age. The Dutch sample had a significantly younger mean age (36 years) than the sample in this study (67 years). In the general population, younger adults evidence significantly higher rates of psychological distress (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008, 2009) and depression (Byers et al., 2010) than older adults. This possibility is further supported by evidence that younger LGB adults evidence significantly higher rates of psychological distress than their older LGB peers (Cox et al., 2009). Thus age may have confounded Kuyper and Fokkema’s (2011) results and may explain other conflicting findings.

Rawls (2004) found that concealing sexual orientation was associated with psychological distress among gay and bisexual men aged 50 to 59 years old, but not among those aged 60 and older. The finding that age is inversely related to psychological distress may be reflective of the general population wherein psychological distress begins to decrease and psychological wellbeing tends to increase around the age of 50 (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008, 2009), a trend that becomes much more pronounced after the age of 65 (Byers et al., 2010). In addition to age, it is also plausible that there is a cohort effect (Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Meyer, 2003). At the time that Rawls’ (2004) study was conducted, those aged 60 and older would have been part of the Silent Generation (b. 1927–1945) and would have come of age during the McCarthy/pre-Stonewall era when LGB people were highly stigmatized and pathologized, and disclosing a non-heterosexual identity could result in the direst of consequences. Those aged 50–59 would have been part of the Baby Boom Generation (b. 1946–1964) and would have come of age post-Stonewall, during the era of the modern gay rights movement, when it was relatively safer to disclose a non-heterosexual identity. Whatever the case may be, LGB older adults still experience unacceptably high levels of psychological distress.

Implications

As the most proximal and chronic of the minority stressors, the role of internalized heterosexism is central to the production of “excess” psychological distress. Its centrality is suggested by both the consistency of findings across studies, samples, differing LGB demographics (i.e., significant association of internalized heterosexism with psychological distress), and the fact that LGB older adults continue to experience disparate rates of psychological distress. Longitudinal, prospective studies suggest that even at low levels, psychological distress significantly increases the risk of early onset of chronic stress-related conditions (e.g., CVD) and consequent mortality (Russ et al., 2012). It is possible that preliminary indications of higher risk of CVD found among lesbian and bisexual older women compared to heterosexual older women (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013) may be related to minority stress–related psychological distress (Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013). At the same time, this study suggests that concealment of sexual identity is a driving force behind internalized stigma, as theorized by Meyer (2003) and Pachankis (2007). It has become generally accepted that disclosing one’s minority sexual identity eventually decreases internalized heterosexism and consequent psychological distress (Herek & Garnets, 2007). However, this may be especially contraindicated among older LGB adults. As individuals age, the need for community-based supports (e.g., senior services) increases, yet heterosexist attitudes and behaviors in such agencies and programs remains the rule rather than the exception (Brotman, Ryan, & Cormier, 2003). Many LGB older adults believe they will need to conceal their sexual identities to access such community supports and to avoid possible discriminatory behaviors and attitudes (National Senior Citizens Law Center, 2011), which places them at risk for increased psychological distress. Discrimination based on sexual identity is a significant predictor of poor physical and mental health outcomes (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Emlet et al., 2013; Herek, 2009). This effectively places LGB older adults between the proverbial rock and hard place.

There are also important ethical implications to consider when the onus is placed on the individual to disclose a marginalized identity to reduce psychological distress, as opposed to addressing the social structures that are the “causes of the cause” (i.e., societal heterosexism) of disparate rates of psychological distress (Meyer, 2003). Because societal heterosexism is a “fundamental cause” of internalized heterosexism and consequent health disparities among LGB populations (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013), both “upstream” (i.e., macro) and “downstream” (i.e., micro) interventions (Gehlert et al., 2008; Williams, Costa, Odunlami, & Mohammed, 2008) are needed to address the goals of Healthy People 2020 in reducing the incidence of depression and health disparities among LGB populations. Policy is one example of an upstream intervention. Recent prospective longitudinal studies have found that in states that have passed pro-LGB legislation, LGB populations experience significant decreases in psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity, while the opposite has been found in states that have passed anti-LGB legislation (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010; Riggle, Rostosky, & Horne, 2010; Rostosky, Riggle, Horne, & Miller, 2009). The mechanism by which these reductions operate remains unclear. It is possible that the concurrent political climate made it more or less safe, respectively, to disclose an LGB identity (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010), although it is also possible that some other mechanism is at work. Yet it stands to reason that whatever the mechanism, ensuring that mainstream, community-based aging services have pro-LGB policies and practices may well have a significant, positive impact on the underlying mechanisms of risk between concealment, internalized heterosexism, and psychological distress among LGB older adults.

Limitations and Next Steps

This study is limited by its cross-sectional nature. Because the sample is not representative, generalizations to the larger population cannot be made. Study participants were drawn from mailing lists of agencies serving the needs of LGBT older adults across the nation. It is possible that participants who are on these mailing lists systematically differ in important ways from LGB older adults who are not associated with such agencies; for example, they may differ in levels of psychological distress, internalized heterosexism, concealment, and other variables. Older LGB adults who remain closeted may be less likely to be connected to such agencies or to allow their names to be on such mailing lists. Similarly, there may be geographic differences, as the agencies are located primarily in major metropolitan areas and may not be accessible to LGB older adults living in rural areas. The majority of study participants were concentrated on the West Coast, in the upper Midwest, and on the East Coast and may differ from those living in the South and Southwest. It is also conceivable that individuals with higher levels of psychological distress may be more likely to conceal their sexual orientation.

While my findings may reflect some of the realities of older LGB adults’ lives, they may also be confounded by measures used to assess concealment and internalized heterosexism; studies that have examined these constructs vary widely in the manner in which these variables have been operationalized. Concealment is likely to be a more complex, dynamic process than simple disclosure or nondisclosure or the relative degree of disclosure. Thus instruments that ask whether and to whom one has disclosed a sexual minority identity may miss important factors that influence the relationship between concealment, internalized heterosexism, and psychological distress. Furthermore, although I controlled for age, there may be unrecognized cohort and period effects in play. It is also likely that other factors influence psychological distress among older LGB adults. Indeed, the minority stress model theorizes several. For example, identity variables such as the centrality of a sexual minority identity relative to other social identities are thought to play a role in minority stress processes. However, the purpose of this study was to focus specifically on the relationship between concealment, internalized heterosexism, and psychological distress.

That internalized heterosexism mediates the relationship between concealment and psychological distress is a preliminary result; replication studies with other samples will help determine the validity of this finding, as well as studies that can capture the full range of minority stressors and buffers. Nonetheless, researchers using the minority stress model to examine health and mental health disparities among sexual minority populations should consider the mediating role concealment. Because the incidence and prevalence of behavioral factors associated with health outcomes such as higher rates of tobacco and alcohol use among LGB groups have also been documented, it will be critical to assess these in models that attempt to explain the associations between minority stress processes and psychological distress. Fredriksen-Goldsen and colleagues (2014) Health Equity Promotion model is an exemplar of such.

Our knowledge of the dynamic interplay of internalized heterosexism and concealment of sexual orientation relative to psychological distress would greatly benefit from longitudinal and prospective study designs using population-based samples. This will require a two-pronged approach. First, the development and implementation of research projects and databases centered on LGB samples can provide unique insights into LGB experience; the incorporation of biomarkers and other measures of physical health would allow researchers to examine whether minority stress processes also affect physical health. Second, the incorporation of questions assessing sexual orientation in extant studies, such as the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the General Social Survey (GSS), and the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), will allow for more robust comparisons between LGB and heterosexual subpopulations across the life course on many variables, such as psychological distress. In addition to helping disentangle age and cohort effects, this knowledge will help to inform culturally relevant and effective interventions, both downstream at the individual level, especially those that target individuals’ management of concealment strategies and consequent internalized heterosexism, and upstream, such as policies to address heterosexism at the societal level.

In conducting research that will lead to culturally relevant and tailored interventions, it will be important to examine both similarities and differences between subpopulations. Possible differences include not only age, cohort, gender, and sexual orientation but also race/ethnicity, nativity, class, and ability. A better understanding of the intersection of multiple social identities will also contribute to knowledge of minority stress processes, while illuminating heterogeneity within the older LGB population. Research would also benefit from the development, validation, and subsequent application of standardized scales of concealment and internalized heterosexism, so that more meaningful and reliable comparisons of results from multiple studies can be made. The validation and uniform application of such measures will be a significant step forward in assuring that that constructs under consideration are, in fact, comparable.

Conclusion

The results of this study offer additional support for the minority stress model in general, and its applicability to older LGB adults in particular. It also provides preliminary evidence for the structural relationship between concealment of sexual identity, internalized heterosexism, and psychological distress, thereby shedding light on a possible “underlying mechanism of risk” (Institute of Medicine, 2011). The important finding that internalized heterosexism mediates the relationship between concealment and psychological distress among sexual minority older adults may also help explain the divergent findings of other studies regarding the association between concealment and psychological distress. The results also suggest that for all the commonalities that LGB older adults share with their younger counterparts, they should also be studied as a distinct population. As such, the results of this study make a contribution to the larger goals of Healthy People 2020, improving the quality of life and reducing health disparities among LGB populations, and the particular objective of reducing the incidence of depression and consequent disease burden.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Karen Fredriksen-Goldsen, Nancy Hooyman, and Taryn Lindhorst for their invaluable input on this article.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was based on Caring and Aging with Pride (CAP) data, which was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG026526 (Fredriksen-Goldsen, PI).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adam B. The rise of a gay and lesbian movement. Boston, MA: Twayne; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Mohr JJ. Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:306–319. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao AM, Swaab DF. Sexual differentiation of the human brain: Relation to gender identity, sexual orientation and neuropsychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2011;32:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1733–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. The U-shape without controls: A response to Glenn. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm SS, Kassin SM, Fein S. Social psychology. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. Gerontologist. 2003;43:192–202. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D. Dissertation. University of Illinois; Chicago, Chicago, IL: 2006. Associations of racial and homosexual stigmas with risk behaviors among Latino men who have sex with men. [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:489–496. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2011;60(Suppl 3):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening guidelines. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/guidelines.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. The state of mental health and aging in America: Issue brief 2: Addressing depression in older adults: Selected evidence-based programs. Atlanta, GA: National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2005;2(1):A14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE. Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0017163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N, Vanden Berghe W, Dewaele A, Vinke J. General and minority stress in an LGB population in Flanders. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2009;4:181–194. doi: 10.1080/15574090802657168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1008–1027. doi: 10.1177/088626001016010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M. Sex and gender are different: Sexual identity and gender identity are different. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:320–334. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007003002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan OD. Recursive models. Introduction to structural equation models. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1975. pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Kim HJ, Muraco A, Erosheva EA, Goldsen J, Hoy-Ellis CP. The physical and mental health of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual (LGB) older adults: The role of key health indicators and risk and protective factors. Gerontologist. 2013;53:664–675. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim HJ, Lehavot K, Walters KL, Yang JP, … Muraco A. The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:653–663. doi: 10.1037/ort0000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:97–10J. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. ATS-14249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: A model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Affairs. 2008;27:339–349. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. The psychology of sexual prejudice. In: Garnets LD, Kimmel DC, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2003. pp. 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:54–74. doi: 10.1177/0886260508316477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:32–43. doi: 10.1037/a0014672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. Employment non-discrimination act. Issue: Federal advocacy. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.hrc.org/laws-and-legislation/federal-legislation/employment-non-discrimination-act.

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L, Fokkema T. Minority stress and mental health among Dutch LGBs: Examination of differences between sex and sexual orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:222–233. doi: 10.1037/a0022688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L, Vanwesenbeeck I. Examining sexual health differences between lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual adults: The role of sociodemographics, sexual behavior characteristics, and minority stress. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:263–274. doi: 10.1080/00224491003654473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simoni JM. The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:159–170. doi: 10.1037/a0022839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda RL. Key advances in the history of structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford; 2012. pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr J, Fassinger R. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000;33:66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Wiseman MC, DeBlaere C, Goodman MB, Sarkees A, Brewster ME, Huang YP. LGB of color and white individuals’ perceptions of heterosexist stigma, internalized homophobia, and outness: Comparisons of levels and links. Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38:397–424. doi: 10.1177/0011000009335263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. Menopause. AgePage. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/healthinformation/publications/menopause.htm.

- National Senior Citizens Law Center. LGBT older adults in long-term care facilities: Stories from the field. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.lgbtlongtermcare.org/authors/

- Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls TW. Disclosure and depression among older gay and homosexual men: Findings from the urban men’s health study. In: Herdt G, de Vries B, editors. Gay and lesbian aging: Research and future directions. New York, NY: Springer; 2004. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Horne S. Does it matter where you live? Nondiscrimination laws and the experiences of LGB residents. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2010;7:168–175. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0016-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Horne SG, Miller AD. Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Starr JM, Kivimaki M, Batty GD. Association between psychological distress and mortality: Individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. British Medical Journal. 2012;345:e4933–e4933. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein C. The implications of removing homosexuality from the DSM as a mental disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:161–163. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9442-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Kashubeck-West S, Meyer J. Internalized Heterosexism: A Historical and theoretical overview. Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:510–524. doi: 10.1177/0011000007309488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Computations for the 2009 annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines for the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia. 2009 Nov 16; Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/09computations.shtml.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020 objectives: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=25.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020 topics & objectives: Older adults. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=31.

- Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, Whitlock E, Charney P, Carter RA. Sexual orientation and health: Comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:843–853. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, Ford CL. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. Journal of Public Health Management. 2008;14(Suppl):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, … Lima VD. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 Item CES-D) among HIV-Positive people in British Columbia, Canad. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]