Abstract

Background

Research supports an association between smoking and negative affect. Loneliness is a negative affective state experienced when a person perceives themselves as socially isolated and is associated with poor health behaviors and increased morbidity and early mortality.

Objectives

In this paper we systematically review the literature on loneliness and smoking and suggest potential theoretical and methodological implications.

Methods

PubMed and PsycINFO were systematically searched for articles that assessed the statistical association between loneliness and smoking. Articles that met study inclusion criteria were reviewed.

Results

Twenty-five studies met inclusion criteria. Ten studies were conducted with nationally representative samples. Twelve studies assessed loneliness using a version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale and nine used a one-item measure of loneliness. Seventeen studies assessed smoking with a binary smoking status variable. Fourteen of the studies were conducted with adults and 11 with adolescents. Half of the reviewed studies reported a statistically significant association between loneliness and smoking. Of the studies with significant results, all but one study found that higher loneliness scores were associated with being a smoker.

Conclusions/ Importance

Loneliness and smoking are likely associated, however half of the studies reviewed did not report significant associations. Studies conducted with larger sample sizes, such as those that used nationally representative samples, were more likely to have statistically significant findings. Future studies should focus on using large, longitudinal cohorts, using measures that capture different aspects of loneliness and smoking, and exploring mediators and moderators of the association between loneliness and smoking.

Keywords: loneliness, smoking, cigarette, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable disease and death globally (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2012; Samet, 2013). Smoking is a modifiable risk factor for cancer, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, poor reproductive outcomes, and other diseases (Office of the Surgeon General (US) & Office on Smoking and Health (US), 2004; Samet, 2013). Efforts to reduce cigarette smoking through cessation and initiation prevention have been successful, but many people continue to smoke (Samet, 2013). Examining correlates of smoking is necessary to improve understanding of smoking etiology and refine smoking reduction efforts.

Research supports that negative affect is associated with smoking (Hall, Muñoz, Reus, & Sees, 1993; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2012). One specific kind of negative affective state is loneliness, which is experienced when a person perceives themselves as socially isolated, or has insufficient quality and/or quantity of social connection as defined by their perspective of the social environment (Hays & DiMatteo, 1987; Laursen & Hartl, 2013). It is a long-recognized human experience which has been operationalized in the form of survey questions useful for empirical research in recent decades (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Focus on loneliness has increased in the public health field as studies have uncovered loneliness as an important, often unaddressed correlate of increased morbidity, early mortality, and poor health behaviors (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2014; Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2003; Noreen E. Mahon, Yarcheski, & Yarcheski, 1998; Perissinotto, Cenzer, & Covinsky, 2012). Mixed findings have been reported regarding the association between loneliness and smoking: some researchers have found that loneliness is associated with smoking, (Christopherson & Conner, 2012; Peltzer, 2009) yet others fail to find an association (Cacioppo et al., 2002; Grunbaum, Tortolero, Weller, & Gingiss, 2000). This review intends to clarify what is currently known about the association between loneliness and smoking, identify gaps in knowledge and evidence, and suggest future research directions.

While various theories explain the experience of loneliness, most research stems from cognitive and psychodynamic perspectives (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989; Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Sønderby & Wagoner, 2013). Psychodynamic and attachment theories led to the development of social needs perspective which suggests that there is a direct association between one’s actual social network and their experience of loneliness (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989). In contrast, cognitive perspectives led to development of self-discrepancy theory which suggests that when one’s ideal social environment does not reflect their actual social environment, loneliness may result (Laursen & Hartl, 2013).

Loneliness may be an evolutionarily selected trait: people who did not experience loneliness may have been less likely to successfully reproduce either due to the reduced motivation to socialize and mate and/or reduced motivation to care for their young (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Therefore, loneliness may serve as a signal to increase social connection and thus increase chances of survival (Cacioppo, Cacioppo, & Boomsma, 2014). This is in agreement with research suggesting loneliness may be experienced as a transient state when a person moves to a new city where they know few people or has a close companion pass away (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989; Peplau & Perlman, 1982). However, loneliness can also act as a social deterrent by causing lonely people to feel unsafe and to perceive their environments as socially threatening, leading lonely people into a loop of distancing themselves from their threatening environment and experiencing increased loneliness due to their lack of social contact (Cacioppo et al., 2006, 2014; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). This may result in loneliness manifesting as a trait, as people may continue to feel the aversive stimuli of loneliness signaling them to reconnect but they also attune to negative social cues in their environment which deter them from being able to act on their instinct to reconnect (Cacioppo et al., 2014; Marangoni & Ickes, 1989; Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Personal and behavioral traits such as poor social skills and low self-esteem may be related to the cycle of loneliness and cause people to be unsuccessful at improving their social environment and to blame themselves for their loneliness, leading to further withdrawal from their social contacts (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989). Variability in loneliness has environmental and genetic influences which affect its successfulness as a survival mechanism (Cacioppo et al., 2014), potentially also influencing its manifestation as a transient state or long-term trait.

Loneliness measures vary in both design and theoretical framework. Some scales separate loneliness into multiple sub-constructs, such as emotional loneliness (loneliness due to lack of close relationships) and social loneliness (loneliness due to lack of a larger social network), while other scales measure loneliness as a uni-dimensional construct (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989; Russell, Cutrona, Rose, & Yurko, 1984; Russell, Peplau, & Ferguson, 1978). Some loneliness scales assess loneliness in specific relationships or social networks while others do not specify which relationships are lacking (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989). Some loneliness scales contain the word lonely in survey items, while others were purposely designed to measure loneliness without the term lonely. Despite their face validity, there is some controversy regarding measures including the term lonely: some people may not recognize themselves as lonely and may not self-identify as lonely and other people may not wish to identify themselves as lonely due to the stigma associated with loneliness (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989). This is often seen in one-item measures of loneliness such as the item “I felt lonely” from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess loneliness (Radloff, 1977). Measurement and theoretical conceptualization of loneliness may alter the association between loneliness and smoking.

Rates of loneliness differ by population (Yang & Victor, 2011). Loneliness may be experienced at higher rates in both the elderly and adolescents, although some studies have found no difference in loneliness by age and others have only found age differences in certain populations (Peplau & Perlman, 1982; Victor & Yang, 2012; Yang & Victor, 2011). Higher rates of loneliness during adolescence may be of importance to smoking prevention because most adult smokers began smoking prior to the age of 18 (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2012). Nationality may affect loneliness as well: a recent paper focusing on differences in loneliness rates by age and nation in 25 European nations found nationality had a larger influence on loneliness in comparison to age (Yang & Victor, 2011). Women have been found to be lonelier than men, (Victor & Yang, 2012) although other studies report higher rates of loneliness in men (Mahon, Yarcheski, Yarcheski, Cannella, & Hanks, 2006). Gender differences are often noted when the word lonely is included in surveys as women may be more likely to identify themselves as lonely (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989; Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Loneliness rates vary by population due to methodological, cultural, and socio-demographic differences.

Various theories and hypotheses explain the potential association between loneliness and smoking. Lonely people may be drawn to the psychopharmacological properties of cigarettes in order to reduce their negative emotions or increase their positive emotions, as suggested by the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1985). DeWall and Pond suggest that motivational processes to increase social acceptance, belonging, and connection may drive lonely people to smoke (DeWall & Pond, 2011). Their theory is based on evidence that lonely people exhibit low impulse control and irrational decision making, both which reduce lonely people’s ability to abstain from unhealthy, yet potentially pleasurable activities such as smoking, and high sensitivity to cues of social affiliation, which may include the presentation of smoking as pro-social behavior (DeWall & Pond, 2011). Borges and Simoes-Barbosa suggest that smokers may anthropomorphize cigarettes and view them as their companions in response to loneliness, using them to fulfill their social needs rather than a tool to instigate actual social connection (Borges & Simões-Barbosa, 2008). Furthermore, the association between loneliness and smoking may differ by population and/or motivation for cigarette use. An association between loneliness and smoking found in adolescents experimenting with smoking or in social smokers may be due to the use of cigarettes to increase social acceptance and connection to peers. An association between smoking and loneliness in established heavy smokers may be attributed to the mood-altering effects of nicotine.

In this paper we systematically review the literature on loneliness and smoking and suggest potential theoretical and methodological implications. Questions addressed include: (1) Is loneliness associated with cigarette smoking?; (2) Does the measurement of loneliness and/or smoking affect the association between loneliness and smoking?; and (3) Is smoking and loneliness only associated in certain populations? Relevance to public health interventions is discussed.

METHODS

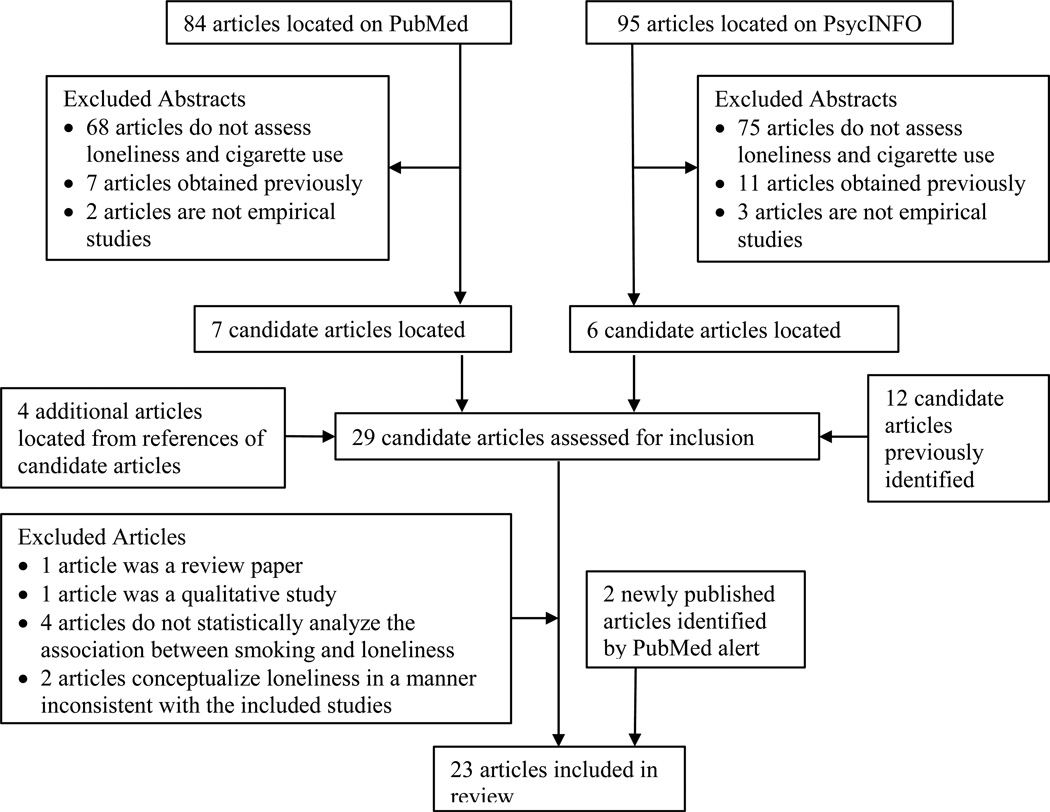

Search engines PubMed and PsycINFO were used to find articles assessing loneliness and smoking. PubMed was searched using the term (lonel* AND (smok* OR cig*)) on January 28th, 2014 and PsycINFO was searched using the term (lone* AND (smok* OR cig*)) on January 29th, 2014. Use of lone* as the search term for loneliness did not appear to pull any additional relevant articles in comparison to the term lonel*. Key words could appear anywhere in the article. Both searches were conducted with filters to include only articles written in English; a filter to include only peer-reviewed articles was also included for the PsycINFO query. No limits on year of publication were included: interest in loneliness and smoking has piqued in recent decades and the majority of articles found were published recently. Reference sections of relevant publications were scanned for additional candidate articles. Articles previously obtained from prior research were also included. A new publication alert was place on PubMed to notify the authors of any newly published literature of relevance. The most recent article included was located by a PubMed alert received on July 24th, 2014.

We included studies that met the criteria of: (1) Loneliness was measured using a quantitative format; (2) Cigarette use or other smoking variable was measured quantitatively; and (3) The association between cigarette use and loneliness was assessed statistically.

RESULTS

There were 23 articles which met the inclusion criteria for the review. Detailed information concerning search results and article exclusion are included in Figure 1. Two articles contained multiple studies that used different methodology (Cacioppo et al., 2002; DeWall & Pond, 2011): these studies will be assessed separately for the remainder of the analysis. Note that only two studies from DeWall & Pond (2011) are reviewed, the third study assessed the association between retrospective childhood rejection and cigarette use and is not included here (DeWall & Pond, 2011). Three articles contained analyses from multiple countries included in the same study but not analyzed as one sample, a consistent methodology was used across the countries included in each study and therefore these studies are reported as one study each (Page et al., 2008; Page, Dennis, Lindsay, & Merrill, 2010; Stickley et al., 2013; Stickley, Koyanagi, Koposov, Schwab-Stone, & Ruchkin, 2014). Therefore, the total study count is 25. In studies with analyses stratified by gender and/or nationality, an overall effect was determined present if at least half of the analyses had statistically significant results.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for article inclusion

Review findings are summarized in Table 1 and descriptions of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Table 1 lists study descriptors, citations for studies within each descriptor category separately for studies with significant and non-significant results, the number of studies in each category, the percentage of studies in each category out of all reviewed studies, the number of studies in each category with significant results for the association between loneliness and smoking, and the percentage of studies with significant findings out of the number of studies in each category.

Table 1.

Summary of review findings on the association between loneliness and smoking

Note.

N*=Number of studies with statistically significant findings

= Percent of studies in category out of all studies included in review.

= Percent of studies in category with significant findings out of all studies included in the category. Percentages rounded to the nearest whole percent.

Table 2.

Summaries of studies included in review

| Publication Information |

Location and year |

Sample description |

Loneliness Measure |

Prevalence loneliness† |

Smoking Measure | Prevalence smoking† |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Allen et al. (1994) Gender differences in selected psychosocial characteristics of adolescent smokers and nonsmokers |

Central Mississippi County, USA |

1679 adolescents sampled from 9th– 12th grades |

ULS-R | Males: M=39.55, Females: M=36.76 |

“How many cigarettes do you smoke during an average day?” Smokers defined as those who report smoking 1+ cigs on an average day. |

Males: 19.2%, Females: 15.8%, Overall: 17.5% |

Smokers scored higher on loneliness than nonsmokers, F(1, 1678) = 7.73, p = .0055. Gender interaction found, male smokers more lonely than all other groups. No difference in loneliness for female nonsmokers and female smokers. |

|

Alwan et al. (2011) Association between substance use and psychosocial characteristics among adolescents of the Seychelles |

Seychelles, 2007 |

1417 nationally representative students aged 11– 17 participating in GSHS |

“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” |

Males: 10.4% Females: 15.2% |

“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Current smokers were defined as having smoked on 1 or more days. |

Males: 22%, Females: 10.6% |

Loneliness was positively associated with smoking for males only in age- adjusted analyses [Males; OR=2.4, 95%CI=(1.3,4.5) p=.008, Females: OR=1.7, 95%CI =(1.0,3.2) p=.065]. The association does not reach significance in multivariate analyses. |

|

Backović et al. (2006) Differences in substance use patterns among youths living in foster care institutions and in birth families |

Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro 2003–2004 |

303 adolescents aged 14–17 living in foster homes (n=58) and with birth family (n=245) |

“Feelings of loneliness”, unspecified measure |

Foster care: 32.8%, Birth family: 16.3% |

Current Smoking, unspecified definition |

Foster care: 55.2%, Birth home: 20.8% |

Loneliness was positively associated with smoking for children in foster care, OR=4.85, 95%CI = (1.36, 17.31), p =.0149. No association for children living with birth families (p =.4773). |

|

Cacioppo et al. (2002) Loneliness and Health: Potential Mechanisms |

Ohio, USA | 89 undergraduate students aged 18– 24 participating in an experimental study |

ULS-R; pts included in analyses if they scored low or high on loneliness |

M = 37.8 | Average # of packs of cigarettes consumed weekly |

Nonlonely= .4 packs/week Lonely= .3 packs/week |

No association between smoking and loneliness (F< 1). |

| Chicago, Illinois, USA |

25 healthy adults aged 53–78 participating in experimental study |

ULS-R, pts included in analyses if they scored low or high on loneliness |

M = 35.1 | Average # of cigarettes consumed daily |

Nonlonely = 2.5 cigs/day, Lonely = 1.07 cigs/day |

No association between smoking and loneliness (F< 1). |

|

|

Christopherson & Conner (2012) Mediation of late adolescent health- risk behaviors and gender influences |

California, USA |

437 students attending a junior college, mean age = 19 |

Revised ULS version 3 |

M = 39.95 | Composite of YRBS measures: How old were you when you smoked a whole cigarette for the first time?”; “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?”; “During the past 30 days, on the days you smoked, how many cigarettes did you smoke per day?” |

M=2.63 (TOB1), M=1.89 (TOB2), M=1.73 (TOB 3) |

SEM indicates higher loneliness was significantly associated with higher scores on the smoking latent factor (Females: B=.28, Males: B=.21)] |

|

Dewall & Pond (2011) Loneliness and smoking: The costs of the desire to reconnect |

USA 1977– 2007 |

89,348 nationally representative high school seniors from MTF |

“Alot of times I feel lonely.” |

NR | “How frequently have you smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days?”, “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?’ |

NR | Loneliness associated with past 30 day cig use (b=0.04, p=.001), and ever having smoked cigarettes (b=0.05, p=.001). Year of administration, gender, and ethnicity included as covariates. |

| USA, 2001– 2003 |

5692 nationally representative adults aged 18–99 from NCS-R |

“Over the past month, how lonely did you feel?” |

NR | “Have you ever smoked a cigarette, cigar, or pipe, even a single puff?”, “Was there ever a period in your life lasting at least two months when you smoked at least once per week?”, “Was there ever a year in your life when you smoked more than you did in the past 12 months?”, “Have you chain smoked for several days or more?” |

NR | Loneliness was associated with having ever smoked[OR=1.17, 95% CI=(1.08,1.28), p<.001], increased likelihood of smoking once per week for at least two months[OR=1.37, 95% CI=(1.18, 1.59), p<.001], smoking more in a past year than in the past 12 months[OR=1.15, 95% CI=(1.05,1.25), p<.002], and chain smoking [OR=1.25, 95%CI=(1.13, 1.37), p<.001], Age, gender, and ethnicity included as covariates. |

|

|

Grunbaum et al. (2000) Cultural, social, and intrapersonal factors associated with substance use among alternative high school students |

Texas, USA, 1997 |

441 Alternative high school students |

ULS, Roberts Version |

NR | YRBS measure: Cigarette use in past month and alcohol use in past month combined. |

60.7% | Loneliness was not associated with combined cigarette/alcohol use, OR=.98, 95% CI=(.94, 1.04). |

|

Hays & DiMatteo (1987) A Short-form measure of loneliness |

California, USA, 1981 |

199 college students aged 17– 48 |

ULS-20, ULS-8, ULS-4 |

ULS-20: M=32.6 |

Composite of quantity of cigarettes smoked (1 ½, 1, ½ less than ½ pack daily, or nonsmoker) and frequency (number of days smoked in past 6 months) |

NR | Smoking was not correlated with any of the loneliness scales; r ranged from −.02 to −.03. |

|

Lauder et al (2006) A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non- lonely populations |

Queensland, Australia 2003 |

1278 nationally representative adults, mean age= 46.25 |

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale |

35% | Participants were asked if they smoke. |

22.3% | Loneliness was associated with smoking [OR=1.55, 95% CI=(1.14, 2.09)]. Marital status, age, employment, gender, and overweight/ obese status included as covariates. |

|

Leung et al. (2008) Validation of the Chinese translation of the 6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in elderly Chinese |

Hong Kong 2007–2008 |

103 Chinese elders aged 62–89 |

Formal Chinese translation of 6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale |

M= 1.5 (range=0–6) |

Current smoking status in comparison to non or ex- smoker. |

NR | Loneliness was correlated positively with current smoking status (r = 0.24; p = 0.014). |

|

Malta et al. (2014) Psychoactive substance use, family context and mental health among Brazilian adolescents, National Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE 2012) |

Brazil 2012 | 9th grade, 109,104 students from PeNSA, sampled using stratified sampling methods |

“In the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” Dichotomized to never sometimes vs. most of the time, always |

NR | Current smoking: “In the past 30 days, how many days did you smoke cigarettes?”, dichotomized to never smoked on any day or one or more days. |

5.1% | Loneliness was associated with smoking [OR=1.27, 95% CI =(1.19, 1.37)], adjusted for all other significant variables in model including age, race, school type, living with parent(s), having meals with parents, family supervision, missing classes w/o permission, insomnia, and having no friends. |

|

Moadel et al. (2012) A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers |

New York, USA |

145 smokers living with HIV age 29–70 participating in a randomized controlled trial |

Revised ULS version 3 |

Abstinent: M= 20.1, Non- abstinent: M=25.4 |

From CDC QIT inventory: “Now, think carefully about the last 7 days. Did you smoke cigarettes, even a puff, on any of those days?” |

14.5% abstinent at end of study |

Loneliness was associated with lower abstinence rates at 3 months [OR=.92, 95% CI=(.85,1.00), p=.04] (reported from intention-to-treat analyses, association retained significance in complete case analysis. Intervention condition, age, ethnicity, quit attempts in past year, positive affect, social situations score, and decisional balance pros score included as covariates. |

|

Page et al. (2008) Cigarette Smoking and Indicators of Psychosocial Distress in Southeast Asian and Central- Eastern European Adolescents |

Thailand, Taiwan, Philippines, |

4518 Southeast Asian adolescent females |

ULS-R | Smoker: M=40.26, Nonsmoker: M=38.59 |

“How often do you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Taiwan=7.6% Thailand=1.8% Philippines=3.2% |

Loneliness was associated with increased smoking, F=9.06 (6, 3753), p = .0026a. |

| Hungary, Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Romania, Czech Republic |

1705 Central- Eastern European adolescent females |

ULS-R | Smoker: M=35.67, Nonsmoker: M=37.22 |

“How often do you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Hungary=36.9% Ukraine=21.3% Slovakia=28.8% Romania=36.5% Poland=35.2% Czech Republic=37.6% |

Loneliness was associated with decreased smoking, F=9.35 (4, 1602), p = .0023a. |

|

| Thailand, Taiwan, Philippines, |

4122 Southeast Asian adolescent males |

ULS-R | Smoker: M=40.39, Nonsmoker: M=40.37 |

“How often do you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Taiwan=15.5% Thailand=5.4% Philippines=5.3% |

Loneliness was not associated with smoking, F=0.00 (6, 3149), p = .9676a. |

|

| Hungary, Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Romania, Czech Republic |

1392 Central- Eastern European adolescent males |

ULS-R | Smoker: M=36.98, Nonsmoker: M=37.55 |

“How often do you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Hungary=31.4% Ukraine=32.6 % Slovakia=23.4% Romania=33.8% Poland=15.3% Czech Republic=34.8% |

Loneliness was not associated with smoking, F=2.13 (3, 1061), p = .1452a |

|

|

Page et al. (2010) Psychosocial Distress and Substance Use Among Adolescents in Four Countries: Phillippines, China, Chile, and Namibia |

Philippines, China, Chile, and Namibia 2003–2004 |

14370 adolescent males from GSHS. Data from Philippines and Namibia are nationally representative. |

“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” |

Smoker= 11.9%, Nonsmoker= 7.6% |

“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Philippines=37. 2%, China=18.2%, Chile=28.1%, Namibia=34.6% |

Loneliness was associated with smoking for the overall sample [OR=1.46, 95% CI=(1.26,1.70)]and all country-specific subgroups with the exception of Filipino males. |

| Philippines, China, Chile, and Namibia 2003–2004 |

16196 adolescent females from GSHS. Data from Philippines and Namibia are nationally representative. |

“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” |

Smoker= 25.4%, Nonsmoker= 11.2% |

“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Current smoking defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Philippines=19. 7%, China=10.1%, Chile=29.1%, Namibia=30.2% |

Loneliness was associated with smoking for the overall sample [OR=2.01, 95% CI=(1.76, 2.29)] and country-specific subgroups with the exception of Chinese females. |

|

|

Peltzer (2009) Prevalence and correlates of substance use among school children in six African countries |

Kenya, Namibia, Uganda, Zimbabwe* 2003–2004 |

12740 students in grades 6–10 from GSHS. Data are nationally representative with exception of Zimbabwe sample. |

“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” |

16.1% | Participants were asked if they smoked cigarettes and/or used any other form of tobacco in the past 30 days. Current tobacco use defined as using any tobacco product in the past 30 days. |

Tobacco use aggregate= 12.6% Smoking= 11.7% |

Loneliness was associated with tobacco use [OR=1.92, 95% CI = (1.89, 1.94), p<.001] in adjusted and unadjusted analyses. |

|

Qualter et al. (2013) Trajectories of loneliness during childhood and adolescence: Predictors and health outcomes |

England, UK | 361 students surveyed from age 7 to 17 |

Peer-related loneliness subscale from the Loneliness and Aloneness Scale for Children and Adolescents |

22% followed a high stable loneliness trajectory |

“Do you smoke cigarettes everyday (1), somedays (2), or not at all (3)?” |

Ranges between 1.43–1.60, reported by loneliness subgroup |

Loneliness latent class not associated with smoking status. The high stable lonely group could not be differentiated from the non-lonely groups in terms of whether they were currently smokers (ORs ≤ 2.21, 95% CI = [.34 –14.51]). The group who increased on loneliness could also not be differentiated from the non-lonely groups (ORs ≤ 1.40, 95% CI = [.70 – 3.44])d. |

|

Shankar et al. (2011) Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults |

England, UK 2004 |

8688 nationally representative older adults from ELSA |

Three-Item Loneliness Scale |

M=4.2 (range 3–9) |

Participants classified as current smokers if they stated they currently smoke. |

Current smoker and physically active:15.9%, Current smoker and physically inactive:6.0% |

Loneliness was significantly associated with smoking in unadjusted analyses. When adjusted for social isolation loneliness was no longer a predictor of being a smoker [OR=1.04, 95% CI=(0.98, 1.09)] but did continue to be a predictor of being both a smoker and having low physical activity [OR=1.08, 95% CI =(1.02, 1.15)]. |

|

Siconolfiet al. (2013) Psychosocial and Demographic correlates of drug use in a sample of HIV-positive adults ages 50 and older |

New York City, NY, USA 2005– 2006 |

811 HIV-positive adults age 50 and older |

Revised ULS version 3 |

M=43.81 | Self-reported if they used cigarettes in the prior 3 months. |

57.2 % | Loneliness was not associated with cigarette use r=.01. |

|

Steptoe et al. (2004) Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle- aged men and women |

London, England, UK |

240 civil servants age 47–59 from Whitehall II prospective cohort |

ULS-R | M=36.3 | Current smoking measured with yes/no question. |

9.7% | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR= 0.98, 95% CI=( 0.93,1.02), p = 0.33]d. |

|

Stickley et al. (2014) Loneliness and health risk behaviours among Russian and U.S. adolescents: a cross- sectional study |

Russia 2003 | 1995 Russian adolescents age 13–15 from SAHA |

Adapted CESD, “I felt lonely.” |

Females= 14.4%, Males= 8.9% |

“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke?” Current tobacco use defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Females= 31.1%, Males=37.1% |

Loneliness was associated with smoking for males and females, the association did not retain significance in females after controlling for depression[Females: OR= 1.10, 95% CI=(.79,1.52), Males: OR=1.87, 95% CI =(1.08,3.24)]c. |

| USA 2003 | 2050 U.S. adolescents age 13–15 from SAHA |

Adapted CESD, “I felt lonely.” |

Females= 14.7%, Males= 6.7% |

“During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke?” Current tobacco use defined as smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. |

Females= 11.2%, Males=7.0% |

Loneliness was not associated with smoking for males; loneliness was associated with smoking for females, the association did not retain significance after controlling for depression [Females: OR=1.86, 95% CI=(.88, 3.94), Males: OR=.72, 95% CI=(.17, 2.97)]c. |

|

|

Stickley et al. (2013) Loneliness: Its Correlates and associations with Health behaviours and outcomes in nine countries of the Former Soviet Union |

Armenia, 2010–2011 |

1605 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

10.7% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi , pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking, OR=1.02, 95% CI=(0.60, 1.75)b. |

| Azerbaijan 2010–2011 |

1650 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

4.4% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=1.03, 95% CI=(0.39, 2.77)]b. |

|

| Belarus, 2010–2011 |

1677 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

8.9% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=0.99, 95% CI=(0.60, 1.66)]b. |

|

| Georgia, 2010–2011 |

1998 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

12.3% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=1.34, 95% CI=(0.81, 2.21)]b. |

|

| Kazakhstan 2010–2011 |

1694 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

5.4% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=1.32, 95% CI=(0.73, 2.39)]b. |

|

| Kyrgyzstan 2010–2011 |

1723 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

7.9% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was associated with smoking [OR=2.29, 95% CI=(1.36, 3.86) p<.01]b. |

|

| Moldova 2010–2011 |

1667 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

17.9% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=0.64, 95% CI=(0.40, 1.03)]b. |

|

| Russia 2010– 2011 |

2549 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

8.1% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=1.10, 95% CI=(0.72, 1.69)]b. |

|

| Ukraine 2010–2011 |

1768 nationally representative adults from HITT |

“How often do you feel lonely?” |

10.8% | “Do you smoke at least one cigarette (papirossi, pipe, cigar) per day?” |

NR | Loneliness was not associated with smoking [OR=1.13, 95% CI=(0.68, 1.87)]b. |

|

|

Thurston et al. (2009) Women, Loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease |

USA 1971– 1975 |

2616 nationally representative adults age 25–74 from NHANES |

CESD, “I felt lonely.” |

9.2% | Smoking status (current versus never/former) |

Low loneliness: 38.8%, Medium=39.1%, High=45.6% |

Loneliness was not associated with smoking (p=.12). Among women only, loneliness was associated with smoking (statistics not reported in paper). |

|

Whisman (2010) Loneliness and the metabolic syndrome in a population- based sample of middle-aged and older adults |

England, UK 2004–2005 |

3211 nationally representative adults age 50+ from ELSA |

Three-Item Loneliness Scale |

M=4.01 (range 3–9) |

Current smoking status (smoker or nonsmoker) |

NR | Loneliness was associated with smoking [OR =1.1, 95% CI=(1.0, 1.2), p< .01]. |

Note. NR=Not reported. GSHS= Global School-Based Health Survey, HITT= Health in Times of Transition, NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Survey, ELSA=English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, MTF=Monitoring the Future, NCS-R=National Comorbidity Survey-Replication, PeNSA=Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde dos Escolares (National Adolescent School-based Health Survey), SAHA=Social and Health Assessment, YRBS= Youth risk behavior survey. Sample sizes reported are the sample sizes used in analyses for the association of loneliness and smoking when data available.

= The overall study included Swaziland and Zambia, however, no data was available on tobacco use in either country and therefore their data was not included in analyses.

= Percentages in column indicate the percent of participants who scored high on the loneliness measure/ indicated that they were lonely or the percent of participants who smoke. Prevalence may be reported only for subsamples in the reviewed article and therefore are presented by subsample here.

=Adjusted for country, age, grade, alcohol use in past week, marijuana or hashish use in past month, and illegal drug use other than marijuana or hashish in the past month.

= Adjusted for sex, age, marital status, education, location, household size, physical activity difficulty, locus of control, wealth, social support, and death of close relative.

=Adjusted for age, family structure, and parental education.

=Statistics not reported in paper. Authors were contacted for the statistical association.

Most studies were conducted within English-speaking countries. Of the studies that indicated when data were collected, all data were collected after 1970. Eleven studies were conducted among adolescents as defined by a mean age of 18 or lower or sampling from schools. The other 14 studies were conducted in adult populations. Ten studies were conducted using nationally representative samples. All study samples were roughly half female with the exception of one composed of adults aged 50 and over living with HIV/AIDS, which was 25.6% female (Siconolfi et al., 2013). Almost all of the studies used cross-sectional survey data, even though some studies pull from longitudinal samples these studies used loneliness and smoking status data collected during only one wave. There were two exceptions: a randomized controlled trial for smoking cessation (Moadel et al., 2012) and a longitudinal study which assessed loneliness trajectories from childhood to adolescence (Qualter et al., 2013).

The most common measure of loneliness was the UCLA loneliness scale (ULS), a full or shortened version of the ULS was used in 12 studies. ULS versions included the revised ULS (ULS-R; Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980), the four-item ULS (ULS-4; Russell et al., 1980), the eight-item ULS (ULS-8; Hays & DiMatteo, 1987), the revised ULS version 3 (Russell, 1996), the ULS Roberts Version---an eight-item version developed for adolescents (Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1993), and the Three-Item Loneliness Scale---a shortened version of the ULS specifically developed for studies conducted on telephone (Hughes, 2004). The other most common measure of loneliness was a one-item likert measure that included the word lonely. Current smoking status was measured in various ways in 13 studies. Four additional articles measured smoking status using the GSHS (Global School-based Health Survey) tobacco measures (Alwan, Viswanathan, Rousson, Paccaud, & Bovet, 2011; Malta et al., 2014; Page et al., 2010; Peltzer, 2009).

Of the 25 studies assessed, 13 (52%) found associations between loneliness and smoking behavior for the main sample. Of the ten nationally representative studies, seven found overall associations between smoking and loneliness. Of the nine studies that measured loneliness using a one-item measure including the word lonely, six had significant findings. Of the 12 studies which used the ULS, five had significant findings.

Some studies contained subgroup analyses and found associations between loneliness and smoking for specific subgroups of participants, including studies which did not find a significant association for the total sample. Seven studies contained analyses stratified by gender (Allen, Page, Moore, & Hewitt, 1994; Alwan et al., 2011; Christopherson & Conner, 2012; Page et al., 2008, 2010; Stickley et al., 2014; Thurston & Kubzansky, 2009) and four studies contained analyses stratified by country (Page et al., 2008, 2010; Stickley et al., 2013, 2014). One study found positive associations between smoking and loneliness for both genders, (Christopherson & Conner, 2012) two studies found a positive association among males but not females (Allen et al., 1994; Alwan et al., 2011) while another study found a positive association for females only (Thurston & Kubzansky, 2009). In a study of four countries, all country-gender subgroups exhibited associations between loneliness and smoking with the exception of Filipino males and Chinese females (Page et al., 2010). A study comparing Russian and American adolescents found that Russian males exhibited a positive association between loneliness and smoking and American males had no significant association (Stickley et al., 2014). The same study had significant results for both Russian females and American females, although the association between loneliness and smoking did not retain significance for either subgroup after controlling for depression (Stickley et al., 2014). Another study exhibited mixed findings in country-gender subgroup analyses: this study reported a notable negative association between loneliness and smoking for Central-Eastern European females, a positive association for Southeast Asian females, and no association for males of either geographic region (Page et al., 2008). Of nine countries from the former Soviet Union, only one country, Kyrgyzstan, exhibited an association between smoking and loneliness (Stickley et al., 2013). In a study of children in Serbia and Montenegro, an association between loneliness and smoking was found only in a subsample of foster children (Backović, Marinković, Grujičić-Šipetić, & Maksimović, 2006).

Studies of smoking during adolescence may be particularly important to focus on because most adult smokers began smoking prior to the age of 18, highlighting adolescence as a prime developmental period for smoking prevention programs (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, 2012). The percentage of studies with significant findings did not differ much between adults (50%) and adolescents (55%). However, the methodology of the adolescent studies did differ somewhat. The adolescent studies were conducted in a greater variety of countries: only 36% of the adolescent studies were conducted in English-speaking nations. Additionally, studies with significant findings in adolescents mostly used a one-item measure of loneliness. Of the 11 studies in adolescents, six used a one-item measure and of these six, five, or 83% had significant findings. Lastly, we highlight that one of the adolescent studies used a longitudinal sample to assess loneliness trajectories, allowing for differentiation between transient and stable loneliness (Qualter et al., 2013). This study did not find a significant association between loneliness trajectories and smoking (Qualter et al., 2013).

DISCUSSION

Overall, half of the studies reported an association between loneliness and smoking. This did not differ when considering the population in which the study was conducted. While not all of the reviewed studies reported a significant association between smoking and loneliness, those that did consistently found that lonely people were more likely to be smokers. Only one study found a negative association between loneliness and smoking, and only for one subsample (Page et al., 2008). Almost three-fourths of the studies that used large, nationally representative samples found significant associations between loneliness and smoking, while less than half of the other studies found a significant association, suggesting that studies need large sample sizes in order to be adequately powered to find an effect. This supports a statement by DeWall and Pond that the association between smoking and loneliness likely has a small effect size and that large samples are necessary to achieve statistical significance (DeWall & Pond, 2011). Due to the variety of populations, measurement instruments, and prevalence of loneliness and smoking in the reviewed studies we do not report an overall effect size for the association between loneliness and smoking. Sample sizes of future studies may be determined using effect sizes available in Table 2 from studies with populations and methodologies similar to proposed studies to adequately power analyses assessing the association between loneliness and smoking.

Over 60% of the studies which measured loneliness using a one-item measure including the word lonely had significant findings while just over 40% of the studies which used the ULS had significant findings. This may suggest that methodological differences account for some of the variability in research findings concerning loneliness and smoking. However, seven of the nine studies which used a single item measure of loneliness also had large, nationally representative samples. It is probable that the large sample size accounts for the higher rate of statistical significance rather than the use of a single item. More research is needed to clarify this. We also note that those studies using one-item measures had higher rates of statistical significance despite concerns of underreporting on these measures due to stigma associated with the endorsement of loneliness (Marangoni & Ickes, 1989). People who self-identify as lonely could potentially be more likely to smoke in comparison to those people who experience loneliness and do not identify themselves as lonely. We also consider that one-item measures may assess a sub-dimension or variant of loneliness which is associated with smoking. Potentially people who identify as lonely are more likely to be chronically lonely or experience a variant of loneliness such as social or emotional loneliness.

Of the nine studies which assessed loneliness using a one-item measure, six were conducted in adolescents. Of these six studies, five (83%) had significant findings, suggesting that one-item measures of loneliness may be particularly useful in adolescent populations. To reconcile the suggestion that one-item measures may assess chronic loneliness with the finding that the longitudinal study conducted in adolescents did not have significant findings we note that the longitudinal study used a measure which assessed peer-related loneliness specifically (Qualter et al., 2013). More longitudinal studies of loneliness and potential loneliness sub-dimensions are necessary to clarify these findings. Endorsement of loneliness may have a different meaning for adolescents and adults. Furthermore, the importance of different kinds of social contacts changes throughout the lifespan (Carstensen, 1992; Fredrickson & Carstensen, 1990). In order to understand the association between loneliness and smoking throughout the lifespan, longitudinal studies conducted with diverse populations and multi-dimensional measures of loneliness are needed.

A variety of smoking measures were used in the studies, however, most of the studies dichotomized their measures to indicate which participants were current smokers. Current smoking was operationalized in different ways throughout the studies. Some studies defined current smokers as those who smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days and other studies defined current smokers as those who smoked daily in the past 30 days. Many studies did not report how current smoking status was defined. The association between loneliness and smoking could potentially be different for established daily smokers and non-daily smokers. The one study that assessed smoking abstinence following a cessation intervention found loneliness to be a predictor of relapse (Moadel et al., 2012). Few other measures of smoking have been assessed for association with loneliness: future studies should include additional measures such as a nicotine dependence scale and describe how variables such as smoking status were assessed.

Ten of the 25 studies were conducted with nationally representative samples: the first of these was published in 2006. This represents a trend of assessing affective states and substance use in the larger population using epidemiological methodology as opposed to smaller studies of psychiatric populations or laboratory studies of healthy participants. In their 2006 study, Lauder and others argue that many studies up to that time had not found an association between smoking and loneliness and that this was due to the use of non-representative, healthy samples in research (Lauder, Mummery, Jones, & Caperchione, 2006). Laboratory-based studies designed to assess physiological correlates of loneliness, like some included here, generally have small sample sizes and low rates of smoking. Without research in larger, representative samples, this review would uncover very different findings. Seven of the 13 studies with significant findings used nationally representative samples. Without those studies there would be little evidence for an association between smoking and loneliness.

Understanding how loneliness induces vulnerability to tobacco use may help program developers design interventions to attenuate the propensity to smoke while experiencing loneliness. Prevention programs may need to address strategies to combat feelings of loneliness other than smoking and to reframe smoking activities from their current position as a potential social bonding activity. Smoking cessation programs may be improved by adding in components to reduce loneliness experienced when quitting smoking. Interventions aimed at reducing loneliness could include a component to reduce negative health behaviors including smoking which may isolate persons and prevent social interaction with the larger population.

There are limitations of this study. Dissertations and theses were not included in the analysis. Many of the studies assessed were cross-sectional and we cannot hypothesize if loneliness is a cause of smoking or if smoking causes loneliness. The association between loneliness and cigarette smoking is likely bidirectional. One study assessed cigarette use and use of other tobacco products together, and one study assessed alcohol use and cigarette use concurrently. Findings reported for these studies may differ if smoking was examined separate from other variables. Many studies used one-item measures of loneliness which do not have preferred psychometric properties and may not have detected more subtle variations in loneliness. While ten of the reviewed studies used nationally representative samples, some studies were conducted with small, non-representative samples such as university students which may not be generalizable to the larger population. Eight reviewed studies did not include data on the sample prevalence of loneliness and/or smoking. Researchers are encouraged to report sample descriptive statistics including prevalence in future studies because lack of variability in loneliness and/or smoking may contribute to null findings. Studies with particularly low or high smoking rates and/or loneliness prevalence may need larger sample sizes and/or stratified sampling methodologies in order to survey enough participants to satisfy statistical requirements to accurately estimate an odds ratio.

Just under half of the studies did not find an association between loneliness and smoking. While this is likely due to these studies being underpowered, there are other potential reasons for this. The association between loneliness and smoking may be population specific or moderated by the prevalence of smoking and/or loneliness, and/or the social context of smoking in a given population. Future studies that include additional measures of demographic variables, nicotine dependence or smoking heaviness, reasons for smoking, and/or coping skills may help explain why loneliness and smoking are associated in some studies, yet no association is found in other studies.

Furthermore, much of the work concerning negative affect and smoking has focused on the bidirectional association of and shared risk factors for depressive symptomatology and smoking (Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2010; Munafò, Hitsman, Rende, Metcalfe, & Niaura, 2008; Steuber & Danner, 2006). Few of the reviewed studies included depression as a covariate in analyses. We note that loneliness was not a significant correlate of smoking in studies that included depression as a covariate. However, given that few studies have examined the associations among loneliness, depression, and smoking, we cannot come to a conclusion concerning their combined associations. Past research suggests that loneliness is predictive of depression in longitudinal studies (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010; Ladd & Ettekal, 2013; Qualter, Brown, Munn, & Rotenberg, 2010). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders includes social impairment as a functional impairment associated with depression, and loneliness is often included in measures of depression such as the CESD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Radloff, 1977). The association between loneliness and smoking may be mediated by depression, or may be spurious due to confounding by depression.

The studies examined do not explain why people who report higher loneliness are more likely to smoke. Various theories provide potential pathways through which loneliness and smoking may impact each other, however, to our knowledge these theories have not yet been tested in the specific association between loneliness and smoking. Loneliness may cause people to smoke either due to self-medication reasons or use of cigarettes to increase social connection (DeWall & Pond, 2011; Khantzian, 1985). Smoking may induce loneliness either through neuro-pharmacological effects of nicotine or social isolation experienced as a smoker. Studies of theoretical models linking smoking and loneliness may provide health promotion program designers with moderating and mediating variables to address during intervention design.

Little research was located examining the association among loneliness and smoking measures within a sample of smokers. Only one study was located which assessed a sample of smokers, and that study only assessed cessation outcomes. A follow-up article on that same sample found that self-efficacy to quit smoking was also significantly associated with loneliness (Shuter, Moadel, Kim, Weinberger, & Stanton, 2014). Future studies conducted within samples of smokers are warranted. Future research should focus on comparing measures of loneliness and studying if single item measures of loneliness which contain the word lonely produce the same association with smoking as multi-item and/or multidimensional measures, given that higher rates of significant findings were found with single item measures in comparison to other measures in the articles located. None of the reviewed studies addressed the difference in the association between loneliness and smoking for loneliness experienced as a transient state or experienced as a prolonged trait. We do not have evidence to suggest if state and trait loneliness operate in different ways. There has been recent emphasis on trajectories of loneliness, (Qualter et al., 2013; van Dulmen & Goossens, 2013). However, research with other measures of loneliness, smoking measures which assess a range of smoking behaviors, and a varied population is still needed to clarify how loneliness is experienced through the lifespan in conjunction with cigarette smoking. Longitudinal studies may contribute to understanding of the directionality of the loneliness/smoking association. It is unclear how motivations to smoke due to loneliness may differ or how the association between smoking and loneliness may change through developmental stages. Our research supports that loneliness and smoking is associated in both adolescent and adult samples. However, little is known concerning the nature of and theoretical reasons for this association. Future research is needed to clarify methodological and theoretical questions and to guide program developers to address loneliness as a component of smoking prevention and cessation interventions.

GLOSSARY

- Loneliness

A negative affective state which is experienced when a person perceives themselves as socially isolated

- UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS)

Measure of loneliness with 20 questions answered on a likert scale. Does not contain the word lonely in any item

Biographies

Stephanie R. Dyal, B.S., is a doctoral candidate in health behavior research at the University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine. She is currently working on her dissertation titled “Adolescent social networks, loneliness, and smoking.” Her research focuses on substance use, social networks, and associated socioemotional factors.

Thomas W. Valente, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Preventive Medicine, Institute for Prevention Research, Keck School of Medicine, at the University of Southern California. He is author of Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications (2010, Oxford University Press); Evaluating Health Promotion Programs (2002, Oxford University Press); Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations (1995, Hampton Press); and over 140 articles and chapters on social networks, behavior change, and program evaluation. Valente uses social network analysis, health communication, and mathematical models to implement and evaluate health promotion programs designed to prevent tobacco and substance abuse, unintended fertility, and STD/HIV infections. He is currently working on specification for diffusion network models and implementing network interventions.

REFERENCES

- Allen O, Page RM, Moore L, Hewitt C. Gender differences in selected psychosocial characteristics of adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Health Values: The Journal of Health Behavior, Education & Promotion. 1994;18(2):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alwan H, Viswanathan B, Rousson V, Paccaud F, Bovet P. Association between substance use and psychosocial characteristics among adolescents of the Seychelles. BMC Pediatrics. 2011;11(1):85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Backović D, Marinković JA, Grujičić-Šipetić S, Maksimović M. Differences in substance use patterns among youths living in foster care institutions and in birth families. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;13(4):341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196(6):440–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges MTT, Simões-Barbosa RH. Cigarro “companheiro”: o tabagismo feminino em uma abordagem crítica de gênero. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2008;24(12):2834–2842. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation: Social Relationships and Health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2014;8(2):58–72. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Boomsma DI. Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition and Emotion. 2014;28(1):3–21. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.837379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3 Suppl):S39–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, Kowalewski RB, Berntson GG. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(3):407–417. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, Spiegel D. Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40(6):1054–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(2):453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7(3):331–338. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson TM, Conner BT. Mediation of Late Adolescent Health-Risk Behaviors and Gender Influences. Public Health Nursing. 2012;29(6):510–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Pond RS. Loneliness and smoking: The costs of the desire to reconnect. Self and Identity. 2011;10(3):375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Carstensen LL. Choosing social partners: how old age and anticipated endings make people more selective. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5(3):335–347. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Tortolero S, Weller N, Gingiss P. Cultural, social, and intrapersonal factors associated with substance use among alternative high school students. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Muñoz RF, Reus VI, Sees KL. Nicotine, negative affect, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(5):761–767. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and pathways to disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S98–S105. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1987;51(1):69–81. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Research on Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142(11):1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Ettekal I. Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder W, Mummery K, Jones M, Caperchione C. A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2006;11(2):233–245. doi: 10.1080/13548500500266607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Hartl AC. Understanding loneliness during adolescence: Developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung GTY, de Jong Gierveld J, Lam LCW. Validation of the Chinese translation of the 6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in elderly Chinese. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(06):1262. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski A, Yarcheski TJ. Social Support and Positive Health Practices in Young Adults: Loneliness as a Mediating Variable. Clinical Nursing Research. 1998;7(3):292–308. doi: 10.1177/105477389800700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski A, Yarcheski TJ, Cannella BL, Hanks MM. A meta-analytic study of predictors for loneliness during adolescence. Nursing Research. 2006;55(5):308–315. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malta DC, Oliveira-Campos M, Prado RR, do Andrade SSC, Mello FCM, de Dias AJR, Bomtempo DB. Psychoactive substance use, family context and mental health among Brazilian adolescents, National Adolescent School-based Health Survey (PeNSE 2012) Revista Brasileira De Epidemiologia = Brazilian Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;17(Suppl 1):46–61. doi: 10.1590/1809-4503201400050005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni C, Ickes W. Loneliness: A Theoretical Review with Implications for Measurement. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1989;6(1):93–128. [Google Scholar]

- Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2012;61(2):208–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafò MR, Hitsman B, Rende R, Metcalfe C, Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103(1):162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2012. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General (US), & Office on Smoking and Health (US) Atlanta (GA): Centers for. Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2004. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44695/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, Dennis M, Lindsay GB, Merrill RM. Psychosocial Distress and Substance Use Among Adolescents in Four Countries: Philippines, China, Chile, and Namibia. Youth & Society. 2010;43(3):900–930. [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, Zarco EPT, Ihasz F, Suwanteerangkul J, Uvacsek M, Mei-Lee C, Kalabiska I. Cigarette Smoking and Indicators of Psychosocial Distress in Southeast Asian and Central-Eastern European Adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38(4):307–328. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.4.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among school children in six African countries. International Journal of Psychology. 2009;44(5):378–386. doi: 10.1080/00207590802511742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. New York: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in Older Persons: A Predictor of Functional Decline and Death. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(14) doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualter P, Brown SL, Munn P, Rotenberg KJ. Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: an 8-year longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19(6):493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualter P, Brown SL, Rotenberg KJ, Vanhalst J, Harris RA, Goossens L, Munn P. Trajectories of loneliness during childhood and adolescence: Predictors and. health outcomes. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. A brief measure of loneliness suitable for use with adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1993;72(3 Pt 2):1379–1391. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Cutrona CE, Rose J, Yurko K. Social and emotional loneliness: an examination of Weiss’s typology of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46(6):1313–1321. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.6.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(3):472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1978;42(3):290–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JM. Tobacco smoking: the leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thoracic Surgery Clinics. 2013;23(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychology. 2011;30(4):377–385. doi: 10.1037/a0022826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuter J, Moadel AB, Kim RS, Weinberger AH, Stanton CA. Self-Efficacy to Quit in HIV-Infected Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siconolfi DE, Halkitis PN, Barton SC, Kingdon MJ, Perez-Figueroa RE, Arias-Martinez V, Brennan-Ing M. Psychosocial and Demographic Correlates of Drug Use in a Sample of HIV-Positive Adults Ages 50 and Older. Prevention Science. 2013;14(6):618–627. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderby LC, Wagoner B. Loneliness: An integrative approach. The Journal of Integrated Social Sciences. 2013;3(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(5):593–611. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuber TL, Danner F. Adolescent smoking and depression: Which comes first? Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(1):133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Koposov R, Schwab-Stone M, Ruchkin V. Loneliness and health risk behaviours among Russian and U.S. adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Roberts B, Richardson E, Abbott P, Tumanov S, McKee M. Loneliness: its correlates and association with health behaviours and outcomes in nine countries of the former Soviet Union. PloS One. 2013;8(7):e67978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(8):836–842. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dulmen MHM, Goossens L. Loneliness trajectories. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1247–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. The Journal of Psychology. 2012;146(1–2):85–104. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.613875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Loneliness and the metabolic syndrome in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older adults. Health Psychology. 2010;29(5):550–554. doi: 10.1037/a0020760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Victor C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing and Society. 2011;31(08):1368–1388. [Google Scholar]