Abstract

This study examined prospective associations between the family context and adolescents’ romantic relationships as moderated by adolescents’ gender and culture among Mexican American families (N = 189). Adolescents at Time 1 (early adolescence) were on average 12.29 years of age (SD = .50) and 54% female. Mothers and fathers reported on family structure and dynamics during early adolescence, and youth reported on their romantic relationship involvement and quality during middle and late adolescence. Results from path analyses indicated that family structure and dynamics (supportive parenting, consistent discipline, parent-adolescent, and interparental conflict) were associated with adolescents’ romantic involvement and quality, with differences by adolescents’ gender and culture. Findings highlight Mexican American family contexts that contribute uniquely to adolescents’ romantic relationships.

Romantic relationships become increasingly important across adolescence as they provide support for youth development and a foundation for later intimate relationships (Collins, Welsch & Furman, 2009). There is evidence that adolescent experiences within the family context are linked to the timing (Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Cauffman, & Spieker, 2009) and quality (Crockett & Randall, 2006) of romantic relationships. Despite calls for greater attention to cultural diversity (Bryant, 2006), research on romantic relationships is lacking for adolescents of Mexican origin (hereafter identified as Mexican American). A focus on Mexican Americans is warranted as this population is the largest U.S. ethnic subgroup (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013a) and one that is relatively young (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013b). The limited research with Mexican Americans suggests cultural factors (Azmitia & Brown, 2002) may intersect with family processes to influence romantic relationships in ways that may differ from other ethnic groups.

The present study addressed three goals. First, it described Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships (duration, partner’s age, ethnicity, and education level), thereby contributing to the scarce data on this subpopulation. Second, it examined prospective associations of the family context (early adolescence) on Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationship involvement (whether they are dating) and romantic relationship quality (perceived intimacy and attachment) two and five years later (roughly middle and late adolescence). Third, it examined the moderating role of adolescents’ gender and culture.

Theoretical and Developmental Frameworks for Examining Family Influences

An ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1986) emphasizes development within overlapping social contexts, including the immediate contexts in which socialization occurs (e.g., family and peer contexts) and the broader cultural forces that further shape youth development. Attachment and socialization theories specifically emphasize the family as a primary developmental context (Bryant & Conger, 2002). From an attachment perspective, relationships with primary caregivers provide the groundwork for later romantic relationships by shaping expectations about the self and others in relationships (Ainsworth, 1989). Socialization theory further specifies parent-child relationship dynamics that influence development through mechanisms such as parental control and supervision, emotional bonds that promote internalization of values and expectancies, and modeling skills that youth use in later romantic relationships (Collins et al., 2009). Drawing on these perspectives, the current study assessed family structure (single-versus two-parent households), parenting processes (supportive parenting and consistent discipline), and family conflict (parent-adolescent and interparental conflict) in early adolescence (7th grade).

Our assessment of romantic relationship outcomes spanned the high school years, a period in which romantic relationships evolve rapidly (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003). As such, a key question this study addressed was whether the family operates to influence romantic relationship outcomes at roughly ages 14 to 15 (9th grade) and at ages 18 to 19 (12th grade). Romantic involvement during these distinct periods tends to be dynamic rather than static for a sizeable majority of adolescents. Youth may also experience differing motivations and family influences. For example, there is evidence that earlier involvement in serious romantic relationships may be motivated by unstable or disrupted family contexts that have been linked to other precocious transitions (e.g., early drinking, pregnancy; Krohn, Lizotte, & Perez, 1997). Also, Scharf and Mayseless (2008) found that mothers played a more salient role in early adolescents’ relationships, whereas fathers’ relationships had stronger effects during later development. However, with the exception of Scharf and Mayseless, prior studies have not examined family influences on romantic relationships at distinct periods.

Describing Romantic Relationships in Adolescence

Evidence from a national sample indicates that 25% of 12 year olds are involved in romantic relationships. This number increases to 50% of 15 year olds and 70% of 18 year olds (Carver et al., 2003). The few studies examining Latinos indicate that they begin dating in groups between ages 14 and 15 and become involved in their first serious relationship between ages 16 and 18 (Raffaelli, 2005). Furthermore, although most Latino youth tend to date romantic partners within their own ethnic group, some research indicates they are more likely to date romantic partners outside their ethnic group as compared to African Americans and European Americans (Joyner & Kao, 2005), with male adolescents reporting higher rates of interracial dating than female adolescents (Raffaelli, 2005). Young men also tend to date younger partners and have relationships of shorter duration, whereas Latinas are more likely to date older partners and report longer lasting relationships (Carver et al., 2003). In this study we provided descriptive information specifically for Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships (duration, partner’s age, ethnicity, and education) and also examined gender differences in these variables.

Family Context and Romantic Relationship Involvement

Romantic involvement refers to whether an individual is dating or in a dyadic relationship with another person with whom they share romantic experiences (Collins et al., 2009). Previous studies support an association between the family context and romantic involvement. For example, studies with European American families found that adolescents were less likely to become involved in romantic relationships at age 15 if they had supportive and high quality interactions with their mothers (Roisman et al., 2009) and were from two-parent as compared to divorced families (Hetherington, 1999). These studies establish a link between adolescents’ family contexts and romantic relationships in early-to mid-adolescence. However, prior research has not examined whether the early adolescent family context also predicts involvement at later ages when most youth are expected to pursue romantic relationships.

Family Context and Romantic Relationship Quality

Scholars have operationalized romantic relationship quality with a variety of measures that typically capture overlapping dimensions of intimacy (e.g., the intensity and frequency of intimacy, closeness) and/or attachment (e.g., affection, connectedness, warmth, and emotional support; Crockett & Randall, 2006; Seiffge-Krenke, Shulman, & Kiessinger, 2001). There is a body of empirical work with primarily European American samples that has found links between the family context and adolescents’ romantic relationship quality. Findings have shown that adolescents are more likely to have higher quality romantic relationships in late adolescence if their earlier interactions with parents were supportive and accepting (Auslander, Short, Succop, & Rosenthal, 2009), their parents used more effective discipline strategies (e.g., lower levels of harsh and inconsistent discipline) to manage youth behavior (Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder, 2000), they experienced less conflict in their relationships with their parents (Reese-Weber & Kahn, 2005), their parents’ experienced less conflict with each other (Cui, Fincham, & Pasley, 2008), and their parents were married as compared to being single parents or divorced (Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2001). Together these findings illustrate that family influences can operate through direct socialization experiences, indirect observational learning, or the detrimental effects of family stress on youth development (Conger et al., 2000; Crockett & Randall, 2006).

Family Influences in Context: Gender and Culture

Consistent with an ecological framework, there are several reasons to expect that gender will play a significant role in the associations between family context and romantic relationships. Accumulating evidence within ethnic groups that value traditional gender roles has found that parents treat daughters and sons differently (Updegraff, Delgado, & Wheeler, 2009). Girls are more oriented toward dyadic relationships in general (Maccoby, 1998) and, in Mexican American families particularly, girls are expected to emphasize family responsibilities and obligations (Azmitia & Brown, 2002). Latinas also report stricter rules about dating and sex than male counterparts (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). Boys, in contrast, receive messages that encourage early dating and sexual involvement and less emphasis on commitment in adolescent romantic relationships. These patterns may promote gender differences in the timing and level of romantic relationship involvement and quality, as well as stronger effects of the family context for girls. The gender intensification hypothesis further emphasizes gender as being important in family socialization processes in early adolescence (Galambos, Almeida, & Petersen, 1990). According to this perspective, girls and boys may be more receptive to socialization efforts by their same-gender parent. Although evidence of gender intensification has been documented in European American (Crouter, Manke, & McHale, 1995) and Mexican American families (Updegraff et al., 2009), it has not been tested with respect to romantic relationships. Thus, we examined gender as a moderator of family context.

The role of culture has rarely been examined in research on adolescents’ romantic relationships (Raffaelli & Iturbide, 2009) and varied and even contradictory hypotheses have been advanced (Raffaelli, Kang, & Guarini, 2012; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). Some prior research indicates that adolescents may experience lower levels of romantic relationship involvement and intimacy in cultures that emphasize strong bonds with family, more frequent interactions with extended relatives, and attachment and loyalty to parents (Ha, Overbeek, de Greef, Scholte, & Engels, 2010). Supportive family bonds and strong expectations regarding family loyalty are hallmark characteristics of traditional Mexican family values (familismo or familism values; Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). Thus, youth with strong ties to their traditional culture may be less likely to become involved romantically or develop strong romantic attachments, particularly in middle adolescence (ages 14–15) when Latino parents are more likely to restrict adolescents’ romantic involvement (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). In retrospective interviews, nearly three-quarters of Latinas reported that their parents did not want them to date before about age 16 (Raffaelli, 2005).

On the other hand, there also is evidence that adolescents’ stronger familism values are associated with positive relationships in general, not only with family but also with peers (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999). Thus, it is possible that adolescents with a strong connection to familism values and culturally-based expectations for interpersonal relationships (e.g., simpatía) may be more likely to replicate positive relationship qualities (high levels of support, low conflict) when they do seek romantic relationships. The interaction of these family and cultural influences may operate to strengthen romantic relationships. It is conceivable that these effects may be most likely to emerge in late adolescence when romantic relationships are more likely to be supported by Latino parents (Raffaelli, 2005). We included measures of adolescents’ Mexican cultural orientation and familism values to test which of these hypotheses was supported in middle and late adolescence, including hypothesized main and moderating effects.

We also examined the role of an Anglo orientation, consistent with integrative models that highlight both “traditional” and “mainstream” cultural orientations as being important, independent dimensions of heterogeneity within U.S. Latino populations (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Research has shown that Latino youth who are more oriented toward mainstream culture may hold liberal attitudes about dating, including the tendency to become romantically and sexually involved at earlier ages (Raffaelli & Iturbide, 2009). Acculturated youth are also more integrated within peer social networks (Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2005), and thus have more opportunities for dating and progression toward serious romantic involvement. Thus, adolescents’ Anglo orientation may influence romantic relationships directly and by moderating family influences. For example, single parent family status and family conflict may be more likely to propel acculturated youth (those high on mainstream Anglo cultural orientation) toward earlier romantic involvement, compared to those low on Anglo orientation, because these youth have more opportunities and models for early romantic and sexual exploration (Raffaelli et al., 2012).

Current Study and Hypotheses

This study first provided descriptive information on romantic relationships for an understudied group, Mexican American adolescents. Second, we examined the family context in early adolescence as linked with romantic relationship involvement and quality two and five years later controlling for family socioeconomic status (SES; Bryant & Conger, 2002). For romantic involvement in middle adolescence, we hypothesized a negative association for two-parent family structure, consistent discipline, and supportive parenting, and a positive association for parent-adolescent conflict and interparental conflict. Prior research has provided a limited basis for predicting relationship involvement at later ages, thus we did not offer directional hypotheses. For romantic relationship quality in middle and late adolescence, we hypothesized a positive association for two-parent family structure, supportive parenting, and consistent discipline, and a negative association for parent-adolescent and interparental conflict. Third, we explored moderation by adolescents’ gender, familism values, and cultural orientations. We proposed alternative hypotheses by which Mexican orientation and familism values may relate to romantic relationship involvement and quality in middle versus late adolescence. We hypothesized negative associations with involvement and quality during middle adolescence, positive associations in late adolescence, and amplification of positive family relationship dynamics (i.e., high levels of parental support, low levels of parent-child and interparental conflict) on romantic relationship quality in late adolescence. For Anglo orientation, we hypothesized positive associations with romantic relationship involvement and quality, and amplification of negative family influences (i.e., single-parent status, parent-adolescent and interparental conflict) on romantic relationship involvement in middle adolescence. For gender, we hypothesized family context effects would be stronger overall for girls, with the exception of stronger effects of the father relationship for boys.

Method

Participants

Data came from a larger longitudinal intervention trial designed to develop competencies for a successful transition from middle to high school among Mexican American youth (N = 516; Gonzales et al., 2012). Students were recruited from four urban schools in the Southwest that served families primarily of Mexican origin (82%) and low income (80% enrolled in free or reduced lunch programs). To be eligible, both a seventh grader and at least one parental figure had to identify as Mexican or Mexican American and be able to participate in the intervention in the same preferred language (English or Spanish). Of eligible families, 62% completed the initial interview, 3% were lost due to mobility, and 35% refused.

The current study used a subset of families from the overall study and included only those families who were randomly assigned to the control group (n = 189). Of these families, 51% had two parental figures participate in the study, and 49% had one parental figure participate (93.5% a maternal caregiver, 6.5% a paternal caregiver). For 97% (n = 183) of families, a maternal caregiver (97% biological mother, here referred to as mothers) participated in the study, and for 54% (n = 102) of families, a paternal caregiver (82% biological father, here referred to as fathers) participated. Most families participated in Spanish (61%).

At the initial interview (referred to as baseline or Time 1; T1), median annual family income was $30,400. Parents had completed an average of 10 years of education (mothers: M = 9.60 years, SD = 3.80; fathers: M = 10.18 years, SD = 4.04). Mothers were on average 37.36 years of age (SD = 6.08) and fathers were 39.36 years (SD = 7.10). Parents were primarily born in Mexico (65.6% mothers; 71.6% fathers) and lived in the U.S. for an average of 16.5 years (mothers: M = 14.83, SD = 7.51; fathers: M = 19.32, SD = 10.14). Most parents were married or in a consensual union as if married (mothers: 84%, fathers: 99%), with the remaining 16% of mothers (3% separated, 7% divorced, 6% single/never married) and 1% of fathers (divorced) in other arrangements. Adolescents were an average of 12.29 years of age (SD = .50), 54% female, 85.7% in two-parent families, and 80.4% born in the U.S.

The second set of interviews (referred to as Time 2 or T2) were conducted two years after T1 when adolescents (Mage = 14.65, SD = .31) were in the 9th grade; 85% of families participated (n = 160). The third set of interviews (referred to as Time 3 or T3) were conducted five years after T1 when most adolescents (Mage = 17.49, SD = .58) were in the 12th grade (23.6% not in school); 77% of T1 families participated (n = 146). T2 non-participating families (n = 29), compared to participating families, reported more paternal years living in the U.S. (M = 28.55, SD = 11.60 vs. M = 17.95, SD = 9.23) with no other differences on T1 demographic variables. T3 non-participating families (n = 43), compared to participating families, reported lower maternal education (M = 8.38, SD = 4.17 vs. M = 9.95, SD = 3.64) and more household members (M = 6.28, SD = 2.28 vs. M = 5.52, SD = 1.99) at T1. Based on these differences, paternal years in the U.S. and household members were included as auxiliary variables in all analyses.

Procedure

Bilingual interviewers conducted in-home computer-assisted interviews with mothers, fathers, and adolescents in their preferred language (English or Spanish). Each family member received $30 for each assessment. The Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Bilingual staff forward and back translated all measures into and from Spanish. All measures met requirements for strong measurement invariance for language of interview (Spanish, English). Thus, we report measure reliability for the full sample across language. Higher scores represent higher levels of each study construct.

Family background characteristics (T1)

Parents were asked their current marital status with responses combined to represent family structure (0 = separated, divorced, or never married, single-parent families; 1 = married or living together as married, two-parent families). Parents reported on total years of education (e.g., 0 = no schooling, 12 = high school diploma, 21 = MD, JD, DO, DDS, or Ph.D.), occupation (e.g., 1 = professional or technical, 13 = student; U. S. Census Bureau, 1992), and household income (parents reported on all sources of income, with sources being summed separately by parent). To create a measure of household income per capita, household income was divided by the number of household members. The highest occupational and educational levels within the family and the log of household income per capita (corrected for skew) were standardized and summed to form a family SES composite variable.

Parenting processes (T1)

Two dimensions of parenting processes (supportive parenting and consistent discipline) were assessed using separate self-reports by mothers and fathers. Supportive parenting was a composite variable created by averaging each parent’s mean scores (1 = almost never or never to 5 = almost always or always) on four separate scales. Parental acceptance (6 items; e.g., “I saw target child’s good points more than his/her faults”), was adapted from the Acceptance subscale of the original Children’s Reports of Parents’ Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Schaefer, 1965). Parent-adolescent attachment (7 items; e.g., “I respected target child’s feelings”) was adapted from parent items of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Parental positive reinforcement (11 items; e.g., “I complimented target child for doing something well”) was developed for the larger study from which this sample was drawn to assess verbal expressions of appreciation, affection, encouragement, and giving tangible rewards (Dumka, Gonzales, Bonds, & Millsap, 2009). Parental personal involvement (four items; “I spent time with target child or did things with him/her alone”), was adapted from the Parent Solicitation subscale developed by Stattin and Kerr (2000). Support for the supportive parenting composite included the high correlations between these scales among mothers (r = .63 to .80) and fathers (r = .64 to .80). Confirmatory factor analyses with the full sample at T1 that included these four scales showed that a one-factor model provided a good fit to the data for mothers, χ2(2) = 11.64, p < .01, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .01, CFI = .99, and fathers, χ2(2) = 4.86, p = .09, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .01, CFI = 1.0. Reliabilities were good (mothers’ α = .90, fathers’ α = .90).

We assessed consistent discipline with four items adapted from the Inconsistent Discipline subscale of the CRPBI (Schaefer, 1965) with items added to assess rule enforcement (e.g., “When I made a rule for my child, I made sure it was followed”). Mothers and fathers reported on their discipline practices on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never or never, 5 = almost always or always), and reliability was acceptable (mothers’ α = .69, fathers’ α = .75).

Conflict domains (T1)

Using an adapted version of measures by Smetana (1988) and Harris (1992), mothers and fathers each reported on the frequency of parent-adolescent conflict on 11 topics (e.g., “How often did you and child disagree or get upset with each other about money”). Parents reported on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never or never, 5 = almost always or always). Reliabilities were good (mothers’ α = .88, fathers’ α = .87). Mothers and fathers also reported on the frequency of interparental conflict on a 6-item scale adapted from Tschann, Flores, Pasch, and Marin’s (1999) Multidimensional Assessment of Interparental Conflict scale and Spanier’s (1976) Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Items (e.g., “How often did the two of you disagree or get upset about money?”) were on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = almost every day) with acceptable reliability (mothers’ α = .71, fathers’ α = .80).

Adolescents’ cultural values and orientations (T1)

We measured adolescents’ familism values (16 items; “It is always important to be united as a family”) with the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010). Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; α =.86). Adolescents rated their Mexican (17 items) and Anglo (13 items) cultural orientations using the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II; Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). Items (e.g., “I enjoy Spanish language TV” and “I think in English”) were rated from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely often or almost always (α = .88, .80 for Mexican and Anglo orientations, respectively).

Adolescents’ romantic relationships (T2, T3)

Adolescents reported on the relationship characteristics of duration in number of months and age of partner at T2, and the duration in months, partners’ ethnicity, and education level at T3. Age of partner was not asked at T3 because we did not want to become aware of potential instances of statutory rape (youth dating partners older than 18). Adolescents reported on relationship involvement by responding to the following questions at T2: “Do you currently have a boyfrie nd or girlfriend?”; “Have you had a boyfriend or girlfriend in the past six months?” and at T3: “Do you currently have a romantic partner?”; “Have you had a romantic partner in the past year?” If adolescents reported dating more than one person, interviewers instructed them to think about the person with whom they were the most serious. The two questions were combined to indicate relationship involvement (0 = no relationship, 1 = in a relationship). We assessed adolescents’ romantic relationship quality with two different but related measures at T2 and T3: intimacy and attachment, respectively. At T2, adolescents reported on their intimacy with partners on a 7-item (e.g., “How much do you go to romantic partner for advice or support”) measure with a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much; Blyth, Hill, & Thiel, 1982; α = .88). At T3, romantic relationship attachment was measured with 9 items (e.g., “You told romantic partner about your worries and problems”) adapted from the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment, included dimensions of trust, communication, and alienation (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), and is highly similar to the T2 intimacy measure. Adolescents reported on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never or never to 5 = almost always or always; α = .88).

Plan of Analysis

First, to describe adolescents romantic experiences during middle and late adolescence, we used a series of one-way ANOVAs examining gender difference in rates of involvement, relationship duration, partner’s age, ethnicity, and education. Second, to examine the proposed study hypotheses, we conducted prospective analyses to examine family predictors of adolescents’ romantic relationship involvement and quality. We also tested for variation in these associations by adolescents’ gender and culture.

We used Mplus 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008–2010) to conduct a series of path analyses including multiple and probit regressions with full information maximum likelihood estimation. We used an analysis strategy (Enders, 2010) that used all available data (N = 189) and included auxiliary variables that were correlated with missingness in an attempt to satisfy the missing at random (MAR) assumption (missingness is dependent on other observed variables). The auxiliary variables included study participation of the respective parent (e.g., mother study participation included in the mother report models), paternal years living in the US, number of household members, relationship involvement in the relationship quality models. We tested the hypothesized models separately for mothers’ and fathers’ reports of family context to determine their independent contributions on adolescents’ romantic relationships. We also estimated separate models for the dependent variables, relationship involvement (0 = no relationship, 1 = in a relationship) and quality (intimacy and attachment) reported 2 and 5 years after baseline (9th and 12th grades, respectively). The independent variables in all models were parents’ reports of family context (T1 family structure, supportive parenting, consistent discipline, interparental conflict, and parent-adolescent conflict). T1 family SES was included as a covariate.

To test the moderating role of adolescents’ gender and culture (T1 familism values, Anglo and Mexican orientations), interaction terms including the moderator of interest and the family context variables (e.g., maternal support X gender) were included in the path models. Adolescents’ gender (0 = girls, 1 = boys) and family structure (0 = single-parent families, 1 = two-parent families) were dummy coded. All other variables were centered prior to the creation of the interaction terms to reduce multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991). The models presented include only significant interaction terms as retaining interactions that are not significant contributes to an increase in standard errors (Aiken & West, 1991). We conducted follow-up analyses for significant interactions as outlined by Aiken and West (1991), including plotting and testing for significant simple slopes either by group for gender or +1SD above and −1SD below the mean on continuous culture moderators.

Results

We first present descriptive information about adolescents’ romantic relationships during middle and late adolescence with tests for gender differences. Then we present prospective analyses examining family predictors of adolescents’ romantic relationship involvement and quality and moderation analyses for adolescents’ gender and culture. Correlations, means, and standard deviations for study variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 family SES | - | .03 | .37* | −.11 | .03 | .06 | −.02 | .07 | .33* | −.18* | .09 | .29* | .02 | .10 |

| 2. T1 family structure (two-parent) | .03 | - | −.23* | .13 | .00 | −.10 | −.06 | .00 | −.15* | .28* | .09 | −.18 | −.09 | .23* |

| 3. T1 P interparental conflict | .03 | −.18* | - | −.07 | .03 | .34* | .03 | −.04 | .27* | −.22* | −.02 | .06 | .14 | −.25† |

| 4. T1 P supportive parenting | .14* | .02 | −.04 | - | .51* | −.04 | .03 | −.01 | .08 | .11 | .16 | .09 | .04 | .25† |

| 5. T1 P consistent discipline | .24* | −.07 | −.08 | .46* | - | .05 | −.03 | −.02 | .12 | −.05 | .12 | .01 | .13 | −.03 |

| 6. T1 P parent-adolescent conflict | −.11 | −.25* | .27* | −.44* | −.12 | - | −.00 | −.14 | .18† | .05 | .14 | −.11 | .20† | −.15 |

| 7. T1 A gender (boys) | −.02 | −.06 | −.08 | −.05 | .03 | .08 | - | .05 | −.07 | .04 | .23* | −.33* | .03 | −.22* |

| 8. T1 A familism values | .07 | .00 | .05 | .01 | .08 | .00 | .05 | - | .17* | .06 | .10 | .27* | −.07 | .08 |

| 9. T1 A AOS | .33* | −.15* | .09 | .08 | −.05 | .01 | −.07 | .17* | - | −.06 | .05 | .28* | −.01 | .05 |

| 10. T1 A MOS | −.18* | .28* | −.24* | −.02 | −.08 | −.03 | .04 | .06 | −.06 | - | .23* | −.17 | −.09 | .10 |

| 11. T2 A relationship involvement | .09 | .09 | −.10 | −.00 | .08 | .18* | .23* | .10 | .05 | .23* | - | .88* | .24* | .03 |

| 12. T2 A partner intimacy | .29* | −.18 | .02 | .17 | −.10 | .01 | −.33* | .27* | .28* | −.17 | .89* | - | .09 | .17 |

| 13. T3 A relationship involvement | .02 | −.09 | −.11 | −.05 | −.07 | .14 | .03 | −.07 | −.01 | −.09 | .24* | .09 | - | .89* |

| 14. T3 A partner attachment | .10 | .23* | −.01 | .12 | .06 | −.10 | −.22* | .08 | .05 | .10 | .03 | .17 | .64* | - |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Father sample | ||||||||||||||

| Full sample M | −.01 | .76 | 1.63 | 3.94 | 3.52 | 1.08 | .46 | 4.50 | 3.90 | 3.35 | .51 | 3.80 | .79 | 4.37 |

| SD | .78 | .43 | .66 | .64 | .92 | .70 | .50 | .43 | .56 | .68 | .50 | .78 | .41 | .65 |

| Boys M | −.02 | .74 | 1.66 | 3.96 | 3.49 | 1.08 | - | 4.52 | 3.86 | 3.38 | .63 | 3.59 | .81 | 4.22 |

| SD | .81 | .44 | .62 | .68 | .96 | .77 | - | .41 | .56 | .71 | .49 | .69 | .40 | .64 |

| Girls M | .01 | .78 | 1.61 | 3.93 | 3.54 | 1.09 | - | 4.48 | 3.93 | 3.33 | .40 | 4.10 | .78 | 4.51 |

| SD | .76 | .41 | .69 | .60 | .88 | .63 | - | .45 | .56 | .66 | .49 | .81 | .42 | .63 |

| Mother sample | ||||||||||||||

| Full sample M | −.01 | .76 | 1.68 | 4.05 | 3.67 | 1.19 | .46 | 4.50 | 3.90 | 3.35 | .51 | 3.80 | .79 | 4.37 |

| SD | .78 | .43 | .63 | .64 | .85 | .77 | .50 | .43 | .56 | .68 | .50 | .78 | .41 | .65 |

| Boys M | −.02 | .74 | 1.63 | 4.01 | 3.70 | 1.25 | - | 4.52 | 3.86 | 3.38 | .63 | 3.59 | .81 | 4.22 |

| SD | .81 | .44 | .56 | .67 | .78 | .73 | - | .41 | .56 | .71 | .49 | .69 | .40 | .64 |

| Girls M | .01 | .78 | 1.73 | 4.08 | 3.65 | 1.13 | - | 4.48 | 3.93 | 3.33 | .40 | 4.10 | .78 | 4.50 |

| SD | .76 | .41 | .70 | .62 | .92 | .80 | - | .45 | .56 | .66 | .49 | .81 | .42 | .63 |

Note. Fathers’ reports presented above the diagonal (n = 102); mothers’ reports presented below the diagonal (n = 183). SES = socioeconomic status. T1 = Time 1 (7th grade; early adolescence), T2 = Time 2 (9th grade; middle adolescence), T3 = Time 3 (12th grade; late adolescence). AOS = Anglo orientation. MOS = Mexican orientation. P = parent report. A = adolescent report. Family structure coded 0 = single-parent families, 1 = two-parent families. Adolescent gender coded 0 = girls, 1 = boys. Involvement coded 0 = not in a relationship, 1 = in a relationship.

p < .10.

p .≤05.

Describing Mexican American Adolescents’ Romantic Relationships

In middle adolescence, 51% of adolescents reported being involved in romantic relationships. Results of the one-way ANOVAs (Table 2) for relationship characteristics suggested that boys (63%) were more likely to be involved in romantic relationships than were girls (40%). Girls were more likely to date older partners than were boys. There was a difference in relationship duration (trend level), with girls reporting longer relationship duration than boys. Turning to late adolescence, 79% of adolescents were involved in romantic relationships, with no significant gender differences. Girls reported longer relationship duration than boys. Although 78% of Mexican American adolescents dated individuals from Latino ethnic backgrounds, girls (85%) were more likely to date romantic partners from their own ethnicity than were boys (70%). Girls’ partner education levels were higher than boys’.

Table 2.

ANOVA Analyses Examining Gender Differences for Mexican American Adolescents’ Romantic Relationship Descriptive Information

| Variables | Total | Boys | Girls | F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| T2 romantic involvement (in a relationship) | .51 | .50 | .63 | .49 | .40 | .49 | 8.64** |

| T2 romantic partners’ age (years) | 15.42 | 1.23 | 15.00 | .77 | 16.03 | 1.51 | 16.24*** |

| T2 relationship duration (months) | 5.63 | 8.58 | 4.26 | 4.86 | 7.59 | 11.87 | 3.01† |

| T3 romantic involvement (in a relationship) | .79 | .41 | .81 | .40 | .78 | .42 | .15 |

| T3 romantic partners’ ethnicity (Latino) | .78 | .42 | .70 | .46 | .85 | .36 | 3.60† |

| T3 romantic partners’ education level (years) | 11.14 | .95 | 10.96 | .99 | 11.31 | .89 | 3.86* |

| T3 relationship duration (months) | 14.79 | 13.71 | 11.76 | 11.93 | 17.51 | 14.70 | 5.19* |

Note. N = 189. T2 = time 2 – 9th grade. T3 = time 3 – 12th grade. Involvement coded as 0 = not in a relationship, 1 = in a relationship. Partners’ ethnicity coded as 0 = non-Latino, 1 = Latino.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Family Context and Romantic Relationships: Prospective and Moderating Associations

Romantic relationship involvement

We first present the consistent results across the maternal and paternal models, prospective main effects, and then moderation findings. Beginning with middle adolescents’ relationship involvement (upper half of Table 3), boys had a higher likelihood of romantic involvement than girls. Higher levels of adolescents’ Mexican orientation were associated with a higher probability of relationship involvement two years later. In the maternal model, there was an interaction between mother-adolescent conflict and adolescents’ gender, indicating for girls (b = .65, SE = .18, p < .001), but not boys (b = .01, SE = .25, ns), higher levels of mother-adolescent conflict were associated with a higher probability of relationship involvement. In the paternal model, there were no other effects.

Table 3.

Summary of Path Models Predicting Adolescent Romantic Relationship Involvement

| Variables | Maternal Report Model | Paternal Report Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | SE b | B | b | SE b | β | |

| Middle Adolescents’ Involvement (T2) | ||||||

| Predictor Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Family structure (two-parent) | .23 | .25 | .10 | .07 | .27 | .03 |

| Supportive parenting | .12 | .19 | .08 | .22 | .18 | .14 |

| Consistent discipline | .06 | .14 | .05 | .09 | .15 | .08 |

| Interparental conflict | −.21 | .18 | −.13 | −.16 | .23 | −.10 |

| Parent-adolescent conflict | .68*** | .19 | .52 | .30 | .18 | .21 |

| Moderator Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Adolescents’ gender (boys) | .50** | .18 | .25 | .54** | .18 | .27 |

| Adolescents’ familism | .10 | .23 | .04 | .27 | .23 | .11 |

| Adolescents’ Anglo orientation | .12 | .19 | .07 | −.05 | .19 | −.03 |

| Adolescents’ Mexican orientation | .42** | .14 | .29 | .37* | .14 | .25 |

| Control Variable (T1) | ||||||

| Family SES | .19 | .16 | .15 | .27 | .17 | .21 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Parent-adolescent conflict X gender | −.60* | .26 | −.30 | |||

| R2 | .33** | .26** | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Late Adolescents’ Involvement (T3) | ||||||

| Predictor Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Family structure (two-parent) | −.22 | .31 | −.09 | −.17 | .35 | −.07 |

| Supportive parenting | .27 | .18 | .17 | .04 | .44 | .03 |

| Consistent discipline | −.22 | .17 | −.19 | .18 | .28 | .17 |

| Interparental conflict | −.27** | .18 | −.30 | .16 | .29 | .11 |

| Parent-adolescent conflict | .40* | .19 | .31 | .40 | .25 | .27 |

| Moderator Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Adolescents’ gender (boys) | .10 | .24 | .05 | .08 | .24 | .04 |

| Adolescents’ familism | −.11 | .28 | −.05 | −.09 | .29 | −.04 |

| Adolescents’ Anglo orientation | −.09 | .26 | −.05 | −.22 | .28 | −.12 |

| Adolescents’ Mexican orientation | −.28 | .18 | −.19 | −.15 | .19 | −.10 |

| Control Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Family SES | .18 | .18 | .14 | −.02 | .20 | −.01 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Supportive parenting X familism | −1.30* | .59 | −.32 | |||

| R2 | .26* | .17 | ||||

Note. Final models include only significant interaction terms. T1 = Time 1 (7th grade), T2 = Time 2 (9th grade), T3 = Time 3 (12th grade). SES = socioeconomic status. Gender coded 0 = girls, 1 = boys. Family structure coded 0 = single-parent families, 1 = two-parent families.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

(N = 189 families)

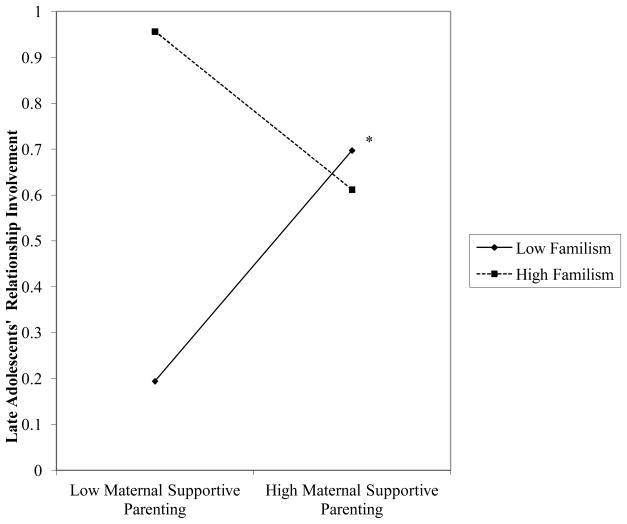

Turning to late adolescents’ relationship involvement (lower half of Table 3), we start with the maternal model. Higher levels of interparental conflict were associated with a lower probability of adolescents’ relationship involvement five years later. Higher levels of mother-adolescent conflict were associated with a higher probability of adolescents’ relationship involvement. There was one moderated effect, maternal supportive parenting by adolescents’ familism values (Figure 1). Under conditions of low levels of adolescents’ familism values (b = 1.48, SE = .66, p < .05), but not high levels of familism values (b = −.88, SE = .80, ns), higher levels of supportive parenting were linked to a higher likelihood of romantic involvement. In the paternal model, there were no significant effects.

Figure 1.

Association between maternal supportive parenting during early adolescence (T1-7th grade) and late adolescence romantic relationship intimacy (T3-12th grade) as moderated by early adolescents’ familism values (T1-7th grade).

Note. Tests of significant simple slopes were used to follow-up the significant interaction. *p < .05.

Romantic relationship quality

For middle adolescents’ intimacy (upper half of Table 4), boys had lower levels of intimacy than girls. Higher levels of adolescents’ familism values were associated with higher levels of romantic intimacy two years later. In the maternal model, higher levels of supportive parenting were associated with higher levels of romantic intimacy. Higher levels of consistent discipline were associated with lower levels of romantic intimacy. There were no significant moderation effects. Turning to the paternal model, higher levels of adolescents’ Anglo orientation were associated with higher levels of relationship intimacy. There was an interaction between paternal consistent discipline and adolescents’ Mexican orientation. Follow-up analyses indicated that under conditions of low levels of adolescents’ Mexican orientation, higher levels of paternal consistent discipline were associated with lower levels of relationship intimacy (b = −.50, SE = .16, p < .01). Under conditions of high levels of adolescents’ Mexican orientation, higher levels of paternal consistent discipline were associated with higher levels of relationship intimacy (b = .31, SE = .14, p < .05). There was also an interaction between fathers’ reports of interparental conflict and adolescents’ gender, but neither simple slope was significant in follow-up analyses.

Table 4.

Summary of Path Models Predicting Adolescent Grade Romantic Relationship Quality

| Variables | Maternal Report Model | Paternal Report Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | SE b | B | b | SE b | β | |

| Middle Adolescents’ Romantic Relationship Intimacy (T2) | ||||||

| Predictor Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Family structure (two-parent) | −.26 | .20 | −.14 | −.18 | .22 | −.09 |

| Supportive parenting | .47** | .14 | .38 | .12 | .14 | .10 |

| Consistent discipline | −.28** | .10 | −.31 | −.10 | .10 | −.11 |

| Interparental conflict | −.11 | .15 | −.09 | .37† | .20 | .29 |

| Parent-adolescent conflict | .16 | .12 | .16 | −.16 | .12 | −.14 |

| Moderator Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Adolescents’ gender (boys) | −.40** | .15 | −.26 | −.39* | .16 | −.24 |

| Adolescents’ familism values | .63** | .19 | .35 | .46* | .19 | .25 |

| Adolescents’ Anglo orientation | .11 | .13 | .08 | .30* | .14 | .21 |

| Adolescents’ Mexican orientation | −.15 | .13 | −.13 | −.15 | .15 | −.13 |

| Control Variable (T1) | ||||||

| Family SES | .15 | .10 | .15 | .12 | .11 | .11 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Consistent discipline X Mexican orientation | .50** | .18 | .35 | |||

| Interparental conflict X gender | −.61* | .26 | −.27 | |||

| R2 | .37*** | .35*** | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Late Adolescents’ Romantic Relationship Attachment (T3) | ||||||

| Predictor Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Family structure (two-parent) | .29* | .14 | .19 | .05 | .15 | .04 |

| Supportive parenting | .12 | .11 | .12 | .35* | .15 | .35 |

| Consistent discipline | .13 | .10 | .17 | −.20* | .10 | −.29 |

| Interparental conflict | .04 | .11 | .04 | −.15 | .11 | −.16 |

| Parent-adolescent conflict | −.06 | .08 | −.07 | −.06 | .10 | −.07 |

| Moderator Variables (T1) | ||||||

| Adolescents’ gender (boys) | −.22* | .11 | −.17 | −.22* | .11 | −.17 |

| Adolescents’ familism values | .15 | .12 | .10 | .08 | .12 | .06 |

| Adolescents’ Anglo orientation | .02 | .11 | .02 | .04 | .11 | .03 |

| Adolescents’ Mexican orientation | .06 | .09 | .06 | .02 | .09 | .02 |

| Control Variable (T1) | ||||||

| Family SES | .10 | .08 | .12 | .06 | .10 | .07 |

| Interactions | ||||||

| Consistent discipline X gender | −.38** | .14 | −.30 | |||

| Supportive parenting X Anglo orientation | .59** | .21 | .35 | |||

| Supportive parenting X Mexican orientation | .31* | .14 | .21 | |||

| R2 | .22** | .34*** | ||||

Note. Final models include only significant interaction terms. T1 = Time 1 (7th grade), T2 = Time 2 (9th grade), T3 = Time 3 (12th grade). SES = socioeconomic status. Gender coded 0 = girls, 1 = boys. Family structure coded 0 = single-parent families, 1 = two-parent families.

p < .10.

p .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

(N = 189 families)

For late adolescents’ attachment (lower half of Table 4), boys had lower levels of romantic attachment than girls. In the maternal model, adolescents in two-parent families, as compared to single-parent families, had higher levels of romantic attachment five years later. There were also two interactions, maternal consistent discipline by adolescent gender, and mothers’ supportive parenting by adolescents’ Mexican orientation. Follow-up analyses revealed that for boys (b = −.28, SE = .11, p < .05), but not girls (b = .15, SE = .13, ns), higher levels of maternal consistent discipline were associated with lower levels of attachment. For mothers’ supportive parenting, under conditions of high levels of adolescents’ Mexican orientation (b = .31, SE = .15, p < .05), but not low levels of Mexican orientation (b = −.05, SE = .13, ns), higher levels of maternal supportive parenting were associated with higher levels of attachment. Turning to the paternal model, higher levels of consistent discipline were associated with lower levels of attachment five years later. There was an interaction between supportive parenting and adolescents’ Anglo orientation, indicating that under conditions of mean (b = .35, SE = .15, p < .05) to high (b = .68, SE = .16, p < .001) levels of adolescents’ Anglo orientation, higher levels of fathers’ supportive parenting were associated with higher levels of attachment.

We performed post-hoc analyses to understand why contrary to our hypotheses high levels of consistent discipline were associated with low levels of relationship attachment. We utilized t-tests to compare the means of adolescents +1 standard deviation above the mean on consistent discipline (n = 29) to all other adolescents on T1 culture variables, externalizing, internalizing, deviant peers, deviant romantic partners, future expectations, academic self-efficacy, GPA, number of partners, substance use, and late adolescents’ attachment. The high group did not differ from the rest of the sample on these variables. Next, because we found an interaction between maternal consistent discipline and adolescents’ gender for late adolescents’ romantic attachment, we examined these differences in the male subsample. Young men high on maternal consistent discipline, compared to the rest of the subsample, were higher on deviant peers’ substance related delinquency, t(20) = 2.21, p < .05; M = 1.80 vs. M = 1.44, and Anglo orientation, t(85) = 2.66, p < .01; M = 3.92 vs. M = 3.45.

Discussion

This study examined multiple domains of the family context during early adolescence in predicting Mexican American adolescents’ later romantic relationships. It is one of the few prospective studies, irrespective of sample ethnicity, to investigate how family context is linked to adolescents’ romantic relationships across a significant period (from early to middle and late adolescence). Overall, study findings supported the hypothesis that adolescents’ earlier experiences within their families prospectively relate to their romantic relationships in high school, similar to prior research with non-Latino samples. However, several unexpected findings also emerged, and hypotheses related to the role of culture and gender received minimal support.

Romantic Relationship Involvement: Descriptive and Family Context Effects

Consistent with previous research with European American adolescents (Crockett & Randall, 2006), a greater percentage of adolescents were involved in romantic relationships in late adolescence as compared to middle adolescence. Similar to findings of Raffaelli (2005) with Latinos, Mexican American girls were more likely to date older partners when compared to Mexican American boys, and boys were more likely to date non-Latino partners. It is possible that boys are more flexible in their dating choices because their parents place fewer restrictions on their dating activities and preferences (Raffaelli, 2005). Also consistent with prior research (Carver et al., 2003), females reported longer relationship durations than males in both middle and late adolescence.

Only one dimension of family context predicted adolescents’ romantic relationship involvement, and this was only in middle adolescence. Mother-adolescent conflict was positively associated with romantic involvement, but only for girls. These findings are consistent with prior research showing conflictual relationships with parents may propel youth toward romantic relationships, potentially prematurely when it occurs at earlier ages (Heifetz, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 2010). This effect may be shown for girls because they are more likely to experience prohibitions and stringent rules against early dating (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). Thus, conflicts or opposition toward mothers may manifest in a tendency for girls to challenge or reject rules and restrictions regarding dating as well. Daughters in Mexican American families also spend more time with their mothers than sons (Updegraff et al., 2009) and experience greater family responsibilities (Azmitia, & Brown, 2002), potentially contributing to greater conflict and stronger effects for girls than boys However, another plausible explanation is that early adolescents girls who engage in more frequent conflicts with parents may be more precocious due to earlier pubertal timing, and this may account for their earlier romantic involvement. Unfortunately, we did not collect information about pubertal timing to examine its potential contribution to parent-child and romantic relationship dynamics.

Although we did not offer hypotheses about the prospective association of family context with late adolescents’ romantic involvement, several associations emerged. Adolescents were more likely to be involved in romantic relationships if they reported greater conflict with mothers in early adolescence, providing further support that romantic relationship formation might be a reaction against struggles with parents or adolescents’ earlier moves toward autonomy. In contrast, adolescents whose mothers reported high levels of marital conflict were less likely to be involved in romantic relationships during late adolescence. This pattern confirms the importance of teasing out the effects of conflict within different family subsystems as they may operate in different ways to influence romantic relationships. Rather than pushing adolescents toward romantic relationships, conflict between parents may dissuade youth from romantic relationships or it may leave them ill-prepared to sustain a committed relationship due to the negative impact of marital conflict on youth emotion regulation and relationship skills (Davies & Lindsay, 2004).

Maternal supportive parenting was associated with relationship involvement in late adolescence, but only for those youth who reported low levels of familism values. Perhaps maternal support is only influential for youth who are less able or inclined to rely on the immediate or extended family for support. Supportive parenting was not associated with early romantic involvement in middle adolescence. Thus, our findings did not support prior research with primarily European American youth that reported a negative association between maternal support and romantic involvement in middle adolescence (Roisman et al., 2009). Instead, we found maternal and paternal support had no effect on romantic relationship involvement in middle adolescence (9th grade), and maternal support was associated with greater likelihood of romantic involvement in late adolescence (12th grade) for a subset of Latino youth. The latter finding may be due to the positive developmental benefits of maternal support that may enable these youth to negotiate the normative task of romantic relationship formation in late adolescence (Collins et al., 2009).

Family Context Effects on Romantic Relationship Quality

Results supported several study hypotheses of family context effects on romantic relationship quality. Consistent with several prior studies with non-Latino samples, adolescents with mothers in two-parent households reported higher levels of relationship attachment during late adolescence (Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2001). It is not surprising that fathers’ family structure did not predict relationship outcomes given the lack of variability in our sample (most fathers were in two-parent families). Also consistent with prior studies, adolescents reported higher quality relationships during both middle and late adolescence if they reported higher levels of maternal support in early adolescence (Auslander et al., 2009; Conger et al., 2000; Seiffge-Krenke et al., 2001). However, effects on late adolescents’ attachment varied as a function of adolescents’ Mexican orientation, with stronger effects at higher levels of Mexican orientation (discussed later). Paternal support also showed a positive association with romantic relationship attachment in late adolescence, but only at mean and high levels of adolescents’ Anglo orientation. Although results varied as a function of culture, the consistent positive impact of supportive parenting on adolescents’ romantic relationship quality was one of the most robust findings shown across time and across gender of parent and adolescent. As a whole, these findings support the basic premise of both attachment and socialization theories that the early family context, particularly supportive and responsive parenting, is a critical determinant of adolescents’ later romantic relationship dynamics.

Although consistent discipline emerged as a predictor of romantic relationship quality, effects were complex and varied by parent gender, relationship timing, adolescent gender, and culture. Maternal consistent discipline was associated with less intimate relationships in middle adolescence, and paternal consistent discipline related to lower romantic relationship attachment in late adolescence, irrespective of adolescent gender and culture. These findings support the conclusion that parents’ strict enforcement of rules and restrictions may hinder youth from developing high quality relationships among Mexican American adolescents. However, maternal consistent discipline interacted with adolescent gender to predict higher levels of romantic relationship attachment in late adolescence, and paternal consistent discipline interacted with Mexican cultural orientation to predict greater intimacy in middle adolescence. For boys only, maternal consistent discipline related to lower levels of relationship attachment in late adolescence, further supporting a negative association. In only one case was the opposite effect shown. Although paternal consistent discipline was associated with less intimacy in middle adolescence for youth less oriented toward Mexican culture, it was associated with greater intimacy for those highly oriented toward Mexican culture.

Notwithstanding this exception (discussed later), the predominantly negative association shown across analyses may indicate that parents’ strict adherence to rules and restrictions largely impede adolescents’ efforts to seek out and establish greater intimacy in romantic relationships. Adolescents in more restrictive families may have less freedom to spend time with romantic partners and to negotiate the give and take required to achieve intimacy within these relationships. Although our findings are opposite to prior findings reported by Conger and colleagues (2000) who found that inconsistent discipline (reverse of consistent discipline) combined with other parenting dimensions such as harsh parenting and low monitoring to predict lower quality relationships, these findings are not directly comparable due to significant measurement differences. Thus, the current findings are novel for the field and will require replication and further efforts to better account for them. Toward this goal, we note that mothers’ reports of consistent discipline were associated concurrently with boys being more oriented toward Anglo culture and associating with substance-using peers (based on post-hoc analyses). The link with peer delinquency might be a third variable implicated in these findings. Another possibility is that parenting dynamics interact to predict relationship quality, such that high consistent discipline and low supportive parenting are associated with lower relationship quality, whereas high consistent discipline and high support are related to higher quality.

The Role of Gender and Culture

We found support for hypotheses involving gender, such that girls reported greater intimacy and attachment, and boys were more likely to be involved in earlier romantic relationships. However, there was only partial support for hypotheses related to gender as a moderator, with evidence of stronger effects of family context only for female middle adolescents’ relationship involvement. Further, there was mixed support for gender intensification theory, suggesting that results may be more congruent with the idea that Mexican American mothers spend more time with children, and thus have more opportunities for socializing both daughters and sons (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). There were more effects for mothers than fathers on adolescents’ romantic relationships overall.

The main effects associated with culture were not as expected, thus warranting further investigation. Adolescents’ orientation toward Mexican culture predicted greater likelihood of a romantic relationship involvement, and familism predicted greater intimacy, both during middle adolescence. Thus, the expectation that a traditional cultural orientation would delay or deemphasize romantic relationship intimacy was countered. These findings suggest, instead, that youth who report involvement with Mexican culture achieved greater intimacy and stronger attachments in their romantic relationships, potentially because close interpersonal connections are more highly valued by these youth. Although there is empirical evidence to suggest that a traditional cultural orientation may delay sexual initiation for Latino youth (Raffaelli et al., 2012), this might not reflect their involvement in romantic relationships. Adolescents may start dating at an early age under strict parental supervision, thus delaying early sexual experiences. It is important for future research to examine both dating and sexual experiences to understand differential connections of these experiences with culture.

Although several findings varied as a function of culture, overall the evidence for cultural moderation was minimal. In only one case did familism emerge as a significant moderator; the positive role of maternal support on late adolescents’ involvement was only for youth who endorsed low levels of familism, as previously discussed. Mexican orientation moderated the effects of paternal consistent discipline on middle adolescents’ intimacy, and moderated the effects of maternal support on late adolescents’ attachment such that maternal support showed stronger effects for youth oriented toward Mexican culture. Conversely, for fathers, an Anglo orientation moderated the effects of support on late adolescents’ romantic attachment, with stronger effects for youth oriented toward mainstream culture. In general, these findings provide some evidence that adolescents’ cultural orientations (both Anglo and Mexican orientation) may amplify family context effects. Given the limited evidence and lack of a clear pattern to these findings, strong conclusions about the moderating role of culture are not yet possible. To gain a better understanding of the role of culture on youth’s romantic relationships, future research should consider using person-centered approaches to examine the variability in cultural orientations and values as related to Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships. Moving beyond a variable-oriented approach to a person-oriented approach would allow for the examination of cultural profiles including biculturalism. Furthermore, there may be additional culturally relevant variables (e.g., traditional gender roles) not available in this study that might further clarify the role of culture in Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationships.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the face of its contributions, the limitations of this study point to important directions for future research. First, we used a specific sample of Mexican American families that agreed to participate together in a family-focused intervention, and thus, may be biased toward cohesive families. It will be important for future research to replicate. Second, prior levels of romantic relationship involvement and quality were not included in our analyses because we did not collect these data. Thus, we were not able to make causal inferences. Also related to our ability to make strong causal inferences, this study tested the effects of earlier family context on later romantic relationship outcomes, but did not examine patterns of change to capture the dynamic nature of these effects across adolescence. We also did not assess whether participants were in their first relationship. This transition may be relevant as parent-adolescent dynamics may influence first dating experiences differently than other types of experiences. Third, not all families had both parents participate, limiting the sample of families with both mothers and fathers. Our small sample size, especially for fathers, may not have provided us with sufficient power to detect small effects. Further, to retain sample size and power, we examined mothers and fathers in separate models, limiting comparisons and the potential to examine combined family effects. Future research should examine independent and reciprocal relations of both mothers’ and fathers’ experiences as family systems theory has emphasized the consideration of mutual influences among family members (Cox & Paley, 2003). Fourth, our study only examined parental influences on romantic relationship development. Future research should examine how other family members, such as siblings and extended kin, influence romantic relationship experiences. There is evidence that siblings, in particular, play an important role (Reese-Weber & Kahn, 2005; Doughty, McHale, & Feinberg, 2013).

Conclusions

This study responds to the call of researchers interested in normative romantic relationship processes among ethnic minority families (Bryant, 2006). Findings emphasize the significant role of mothers and, to some extent, fathers in Mexican American adolescents’ romantic relationship experiences. Some of our findings were similar to prior empirical evidence with European Americans, including the influence of family conflict processes, parental support, and family structural characteristics on romantic relationship development. However, findings also differed for this sample. Thus, we provide insights into how Mexican American family contexts and processes may contribute uniquely to the adolescent developmental task of romantic relationship formation and dating and raise new questions for future research to pursue.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant, R01 MH64707. We are grateful to the families who participated in this project and to the following districts and schools that collaborated: Cartwright School District, Phoenix Elementary District #1, Marc T. Atkinson Middle School, Desert Sands Middle School, Frank Borman Middle School, Estrella Middle School, and Phoenix Preparatory Academy.

Footnotes

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the Biennial Meeting for the Society for Research on Adolescence, Vancouver, Canada, March, 2012.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auslander BA, Short MB, Succop PA, Rosenthal SL. Associations between parenting behaviors and adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia A, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth D, Hill J, Thiel K. Early adolescents’ significant others: Grade and gender differences in perceived relationships with familial and non-familial adults and young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1982;11:425–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01538805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.22.6.723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM. Pathways linking early experiences and later relationship functioning. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Romance and sex in adolescence and early adulthood: Risks and opportunities. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Conger RD. An intergenerational model of romantic relationship development. In: Vangelisti AL, Reis HT, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Stability and change in relationships. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:157–174. doi: 10.1002/jcp20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GH. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Paley B. Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:193–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Manke BA, McHale SM. The family context of gender intensification. Child Development. 1995;66:317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA. Linking adolescent family and peer relationships to the quality of young adult romantic relationships: The mediating role of conflict tactics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:761–780. doi: 10.1177/0265407506068262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans - II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Fincham FD, Pasley BK. Young adult romantic relationships: The role of parents’ marital problems and relationship efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1226–1235. doi: 10.1177/0146167208319693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: Why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:160–170. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty SE, McHale SM, Feinberg ME. Sibling experiences as predictors of romantic relationship quality in adolescence. Journal of Family Issues. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0192513X13495397. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, Millsap RE. Academic success of mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles. 2009;60:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Almeida DM, Petersen AC. Masculinity, femininity, and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development. 1990;61:1905–1914. doi: 10.2307/1130846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap RE, Gottschall A, McClain DB, Wong JJ, Germán M, Mauricio AM, Wheeler LA, Carpentier FD, Kim SY. Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0026063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Overbeek G, de Greef M, Scholte RH, Engels RC. The importance of relationships with parents and best friends for adolescent romantic relationship quality: Differences between indigenous and ethnic Dutch adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:121–127. doi: 10.1177/0165025409360293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris VS. But dad said I could: Within-family differences in parental control in early adolescence. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1992;52:4104. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz M, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W. Family divorce and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 2010;51:366–378. doi: 10.1080/10502551003652157.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM. Social capital and the development of youth from nondivorced, divorced, and remarried families. In: Collins WA, Laursen B, editors. Relationships as developmental contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1999. pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Kao G. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:563–581. doi: 10.1177/000312240507000402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Perez CM. The interrelationship between substance use and precocious transitions to adult statuses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:87–103. doi: 10.2307/2955363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide: Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M. Adolescent dating experiences by Latino college students. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Iturbide MI. Sexuality and sexual risk behaviors among Latino adolescents and young adults. In: Villarruel FA, Carlo G, et al., editors. Handbook of US Latino psychology: Developmental and community based perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Kang H, Guarini T. Exploring the immigrant paradox in adolescent sexuality: An ecological perspective. In: Garcia Coll C, Marks A, editors. Is becoming an American a developmental risk? Washington, DC: APA Books; 2012. pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50:287–299. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018886.58945.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reese-Weber M, Kahn JH. Familial predictors of sibling and romantic-partner conflict resolution: comparing late adolescents from intact and divorce families. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.09.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Cauffman E, Spieker S. The developmental significance of adolescent romantic relationships: Parent and peer predictors of engagement and quality at age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1294–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9378-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. doi: 10.2307/1126465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf M, Mayseless O. Late adolescent girls’ relationships with parents and romantic partner: The distinct roles of mothers and fathers. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:835–855. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Shulman S, Kiessinger N. Adolescent precursors of romantic relationships in young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2001;18:327–346. doi: 10.1177/0265407501183002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents’ and parents’ conceptions of parental authority. Child Development. 1988;59:321–335. doi: 10.2307/1130313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child-Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:242–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Flores E, Pasch LA, Marin BV. Assessing interparental conflict: Reports of parents and adolescents in European American and Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:269–283. doi: 10.2307/353747.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Delgado MY, Wheeler LA. Exploring mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with sons versus daughters: Links to adolescent adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Sex Roles. 2009;60:559–574. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 1990 Census of population and housing, alphabetical index of industries and occupations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1992. 1990 CPH-R-3. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic Heritage Month 2013. 2013a Retrieved July 7, 2014 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/cb13ff-19_hispanicheritage.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Facts for Features: Cinco de Mayo. 2013b Retrieved July 7, 2014 from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb12-ff10.html.