Abstract

Ethno-political conflict impacts thousands of youth globally and has been associated with a number of negative psychological outcomes. Extant literature has mostly addressed the adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes of exposure while failing to examine change over time in social-cognitive factors in contexts of ethno-political conflict. Using cohort-sequential longitudinal data, the present study examines ethnic variation in the development of negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups among Palestinian (n=600), Israeli Jewish (n=451), and Israeli Arab (n=450) youth over three years. Age and exposure to ethno-political violence were included as covariates for these trajectories. Findings indicate important ethnic differences in trajectories of negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups, as well as variation in how such trajectories are shaped by prolonged ethno-political conflict.

Ethno-political conflict impacts thousands of youth around the world every day and has been associated with a number of negative psychological outcomes (e.g., Boxer et al., 2013; Cummings et al., 2010; Dubow et al., 2012a, 2012b; UNICEF, 1996). Although literature on the impact of ethno-political violence on youth has been increasing (e.g., Barber, 2009; Boxer et al., 2013), it has mostly addressed the adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes of exposure while failing to examine changes over time in social-cognitive factors that also might be sensitive to ethno-political violence exposure (Barber, 2009; Barber & Olsen, 2009). This is surprising given the long line of social psychological research illustrating the tendency to differentiate between members of in-groups and out-groups and to subsequently negatively evaluate out-groups (see review by Brewer & Brown, 1998; Leyens, Yzerbyt, & Schadron, 1994), particularly in contexts of violence, threat and ostracism (Bar-Tal, 2000, 2004; Dixon, 2008; Stangor & Schaller, 1996). This tendency is often coupled with the development of negative and dehumanizing beliefs and stereotypes about the “other” (Schwartz & Struch, 1989), which is heightened in contexts of continuing and intractable ethno-political conflict (Oren & Bar-Tal, 2007). In contexts of ethno-political violence, negative and dehumanizing stereotypes of the “other” not only act as the outcomes of animosity between the involved groups, but also act to perpetuate the conflict by creating a cognitive basis for the hostility and mistrust between groups (Oren & Bar-Tal, 2007).

While the extant literature offers insight into how ethno-political violence may influence social-cognitive development, research is predominantly cross-sectional. Little research to date has examined the development of negative and dehumanizing stereotypes of ethnic out-groups longitudinally, particularly in a context of conflict that heightens and intensifies in-group and out-group status. We examine the development of negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups in a longitudinal study of Palestinian, Israeli Jewish, and Israeli Arab youth. In accordance with prior theory and research on the relation between ethno-political violence and social-cognitive beliefs and stereotypes (Dubow, Huesmann, & Boxer, 2009; Huesmann et al., 2012), we hypothesized that youths’ negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups would increase over time, especially in relation to exposure to ethno-political violence.

The Development of Stereotypes

The development of stereotypes, particularly in the context of intergroup relations and conflict, has long been explored (Allport, 1954/79). Stereotypes have been defined in myriad ways. At its most basic level, stereotypes are a socially shared set of beliefs about traits that are characteristic of members of social categories (e.g., ethnicity, nationality) (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Social stigma and negative stereotypes can have detrimental implications for those who are targets of stereotypes. They have been negatively associated with self-esteem, academic achievement, mental health, and physical health (Major & O'Brien, 2005). Further, stereotypes shape identity development, experiences of discrimination, and intergroup conflict (e.g., Niwa, 2012; Peguero, 2009; Way et al., 2008).

Stereotypes are learned at the nexus of social interactions and cognitive development. Social Cognitive Information-Processing Models (e.g., Bandura, 1986; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Huesmann, 1998) argue that observations of one's environment shape all domains of development. This literature emphasizes the inextricable link of the social and cognitive developmental domains, particularly as it relates to the categories and schemas within which we identify and categorize individuals into groups. From this perspective, stereotypes are an important component of a person's schema about social categories, such as ethnicity or nationality (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Whereas the cognitive capacity to categorize starts in early childhood, ethnic categories, and more abstract categories such as nationality, begin to increase during middle childhood and adolescence (e.g., Stangor & Schaller, 1996). In particular, youth develop increasingly complex schema, or abstract knowledge structures, that give meaning to social information and represent beliefs about characteristics of a social group (Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Markus & Zajonc, 1985). These schemas allow individuals to categorize and evaluate others and are expected to increase in complexity over time as adolescents gain a better understanding of social group membership and related biases (e.g., Erikson, 1968; Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Spencer et al., 1997). Further, while individuals use their beliefs about social groups to help them understand individual behavior, stereotypes also develop at the cultural level and confer meaning to social events, such as ethno-political violence (Bar-Tal, 2004; Hewstone, 1990; Stangor & Schaller, 1996; Tajfel & Forgas, 2000).

The development of stereotypes about others, which is shaped by changes in social-cognitive abilities (Quintana, Castaneda-English, & Ybarra, 1999), is particularly important during middle childhood and adolescence. During this period, adolescents understand and grapple with social categories (e.g., ethnicity) and the stereotypes associated with them (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Huesmann, Dubow, Boxer, Souweidane, & Ginges, 2012; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997). Consequently, they use their growing sense of group membership, and corresponding stereotypes, as a central lens through which they view and evaluate both the self and others (Erikson, 1968; Spencer et al., 1997; Way, Santos, Niwa, Kim-Gervey, 2008).

Beliefs About the “Other”

Categorization through stereotypes is a cognitive mechanism used by individuals to process information about others. It also offers self-evaluative benefits that emerge in the process of differentiating one's own group from others (Mackie, Hamilton, Susskind, & Rosselli, 1996; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). These include attributing positive qualities to the in-group and negative qualities to out-groups (Bar-Tal, 2000; Brewer & Brown, 1998; De Cremer, 2001; Hewstone, 1990; Schwartz & Struch, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Negative stereotypes can take many forms and fall on a continuum of intensity ranging from fairly mild to quite severe. Perhaps the most intense stereotypes are those that dehumanize out-groups. Negative stereotypes representing dehumanizing beliefs about out-groups are often viewed as both an important precondition and consequence of violence (for review, see Haslam, 2006) and thus may hold particular importance in contexts of ethno-political violence (Bar-Tal, 2000; Moore & Guy, 2012).

Delegitimizing beliefs are an extreme form of dehumanization in which extremely negative characteristics are attributed to another group, with the explicit purpose of excluding them from “acceptable” human groups and thus denying their humanity (Bar-Tal, 1996, 2000). These delegitimizing beliefs are theorized to be products of interethnic conflict, such as in the Middle East, and serve multiple functions. These functions include the ability to explain the conflict, justify the in-group's aggression against the out-group, and provide individuals from the in-group with a sense of superiority (Bandura, 2002; Bar-Tal, 2000; Haslam, 2006). In Bar-Tal's extensive work with Israeli youth, he has noted the powerful role of delegitimizing beliefs. For example, in one study, Bar-Tal (1996) found that Israeli Jewish children characterized Arabs using delegitimizing categories (e.g., “killers,” “murderers”). These categories not only reflected outcasting, but was based on their exposure to delegitimizing information about terrorist attacks and negative cultural stereotypes transmitted through parents, teachers, peers, and the media. Ultimately, protracted ethno-political violence can end up strengthening unity related to the in-group, as well as delegitimizing beliefs regarding the out-group. Such beliefs lead to increased negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups and may further prolong the conflict (Moore & Guy, 2012; Oren & Bar-Tal, 2007).

Negative Stereotypes in the Context of Ethno-political Violence

Individual development, including the development of stereotypes, does not occur in a vacuum, but rather is embedded in the multiple contexts of youths’ lives (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). These contexts extend from proximal (microsystem) to distal (macrosystem) levels. Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) argues that cognitions about both the self and the “other” are inextricably linked to an individual's contexts, including ethno-political violence (Boxer et al., 2013). The macrosystem, which includes the beliefs and ideologies in a given culture, is believed to influence development through the instantiation of “consistencies” and acts as the backdrop to interactions in proximal contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, p.26). It is particularly important in contexts of violence, political exclusion, and oppression (Moane, 2003).

Stereotypes about ethnic groups exist across all levels of context and are part of the “social heritage of society” (Mackie et al., 1996, p.35). They are passed down both directly (e.g., through interactions with others) and indirectly (e.g., through media, political/religious leaders) (Stangor & Schaller, 1996). The acquisition of stereotypes more generally is expected across all contexts. Tthe acquisition of negative stereotypes in particular, however, is expected to increase under conditions in which conformity pressures are highest, such as in intergroup conflict, which requires loyalty, solidarity, and adherence to group norms. These conformity pressures are expected to be associated with widespread endorsement of negative stereotypes about out-groups (e.g., Mackie et al., 1996). Further, the need to simplify and structure understanding of others through stereotypes may be heightened during times of crisis (e.g., protracted exposure to ethno-political violence) when leaders purposefully use stereotypes to stifle dissent, clarify behavioral and cultural norms, justify aggressive behavior, and reduce potential ambiguity about one's “side” (Stangor & Schaller, 1996). In fact, when national or racial groups are engaged in recurring cycles of violence, neither group is likely to see their own role in the cycle, but rather will view the “others” as more irrational, stubborn, or aggressive (Mackie et al., 1996).

The development of negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups may be especially profound in contexts of “intractable” ethno-political violence, such as in the case of Israelis and Palestinians (Bar-Tal, Raviv, Raviv, & Dgani-Hirsh, 2009; Oren & Bar-Tal, 2007). For example, studies indicate that negative stereotyping of Palestinians by Israelis increased after the failure of the Camp David Peace Summit (Bar-Tal, 2004). Prior to the Peace Summit, 39% of Israelis described Palestinians as violent and 42% described them as dishonest. After the failure of the peace talks, when it was widely portrayed in the Israeli media as being the Palestinians’ fault (Bar-Tal, 2004), these percentages changed to 68% and 51% for perceiving Palestinians as violent and dishonest, respectively (Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research, 2000).

The Present Study

We utilized data drawn from a cohort-sequential longitudinal study of children's psycho-social development in the context of persistent ethno-political violence (Boxer et al., 2013; Dubow et al., 2012a, 2012b; Landau et al., 2010). Children were sampled from Israel and Palestine and data were collected from three cohorts, with starting ages of 8, 11, and 14 years. We hypothesized that, due to increasing social-cognitive skills including the development of cognitive schema, negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups would increase over time as youth get older. Further, we expected that there would be significant ethnic differences in the levels and changes over time of negative stereotypes as the three different ethnic groups experience the conflict in varying ways. In particular, while Israeli Jews maintain a position of political power, they face the perceived existential threat to Israel by outsiders (Bar-Tal, 2004). Palestinians are Arabs who were displaced after the formation of Israel and Israeli political control affects their social, economic, and daily realities (Moore & Guy, 2012; Ugland & Tamari, 1993). Finally, Israeli Arabs are citizens of Israel who also identify as Arabs or Palestinians (Shikaki, 1999; Shtendal, 1992). Based on these complex ethnic-national categories, we hypothesized that Palestinians and Israeli Jews would report higher levels and steeper increases in negative stereotypes than their Israeli Arab counterparts, as Israeli Arabs share a national identity with their ethnic out-group (Israeli Jews). We also predicted that higher levels of exposure to ethno-political violence would be associated with steeper increases over time in negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups across all three ethnic groups.

Method

Sampling Procedures

Data are from three waves of a larger longitudinal study on the effects of exposure to violence on behavioral and mental health in three cohorts of youth (8, 11, 14 years at Wave 1) growing up in Palestine (N = 600) and Israel (N = 901; 451 Israeli Jewish, 450 Israeli Arab).

Palestinian sample

At wave 1, the Palestinian sample is a representative sample (N = 600), which included 200 8-year olds (101 girls, 99 boys), 200 11-year olds (100 girls, 100 boys), and 200 14-year olds (100 girls, 100 boys), along with one of their parents (98% were mothers). Residential areas were sampled proportionally to achieve a representative sample of the general Palestinian population with the use of census maps of the West Bank and Gaza as provided by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Our sampling procedure included the following process. Palestine was divided into two areas: West Bank (64% of the sample) and Gaza Strip (36% of the sample), and counting areas were divided according to size. One hundred counting areas were selected randomly. In each counting area, a sample was selected whereby six children would be interviewed, three boys and three girls divided equally over the three targeted ages. Houses in each counting area were divided to allow random selection of six homes. In the first home, an interview could be conducted with any one of the six types of children needed; if there were more children who fit the description, one was selected using Kish Household Tables. In the second home, the age and gender type of child selected in the previous home would be excluded and so the choices would become five, rather than six, and so on. Sixty-one families declined to be part of the sample (rejection rate = 10%). Staff from the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research conducted the sampling and interviews. Almost 100% (599 of 600) of the parents reported being Muslim and 99% were married.

One-third of the parents reported having at least a high school degree, and 47% reported their incomes as below the Palestinian average (33% = average, 20% = above average). Parents reported that on average, there were 4.89 (SD = 1.86) children in the home. These statistics are representative of the general Palestinian population based on the 2007 census (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008). At Waves 2 and 3, 590 and 572 Palestinian children and their parents were re-interviewed (resampling rates of 98% and 95% respectively). Interviewing at Wave 3 was briefly interrupted by the 2009 incursion of Israeli troops into Gaza (Operation Cast Lead), but the disruption in interviewing only lasted 2 weeks. T-tests of Wave 1 study variables revealed that attrition was not associated with any of the study variables.

Israeli sample

The Israeli sample included 901 children and their parents who were either identified as Israeli Arab or Israeli Jewish. Israeli Arabs are Arabs who are citizens of and reside within Israel. They therefore share an ethnicity with Palestinians, while sharing a nationality with Israeli Jews. The Israeli Arab group consisted of 450 children: 150 8-year olds (66 girls, 84 boys), 149 11-year olds (69 girls, 80 boys) and 151 14-year olds (79 girls, 72 boys) and one of their parents (68% were mothers). The Israeli Jewish group consisted of 451 children: 151 8-year-olds (79 girls, 72 boys), 150 11-year-olds (73 girls, 77 boys), and 15014-year-olds (94 girls, 56 boys), and one of their parents (87% were mothers).

In comparison to the level of conflict and violence in Palestine, the level of conflict and violence is relatively low in the major population centers of Israel; thus high-risk areas were oversampled. Of the Arab sample, 7% live in Jerusalem, 70% live in the north (near the Lebanese border), and 23% live in central Israel (low conflict area). Of the Jewish sample, 15% live in Jerusalem, 25% live in the north, 23% live in the south (around the Gaza Strip), 24% live in the occupied West Bank, and 14% live in central Israel.

Families were approached in one of three ways: (a) recruitment by phone—random phone calls were made to households in the designated area, and the respondents were asked to participate if they had children in one of the age cohorts, (b) recruitment by cluster sampling—we randomly selected neighborhoods and streets in the designated area, and then interviewers went door-to-door locating families with children fitting the sample criteria and asked them to participate, and (c) non-probability sampling—interviewees were allowed to recommend families who fit the sample criteria. Each family's census data were verified, and if they were demographically eligible, the family was included in the sample. Face-to-face interviews were scheduled for those who agreed to participate (55% of Jewish sample and 65% of Arab sample). Staff from the Mahshov Survey Research Institute conducted the sampling and interviews.

Among the Israeli Jewish sample, 91% of the parents were married, over 80% had graduated from high school, and 42% reported their incomes as below the Israeli average (28% = average, 30% = above average). Parents reported that on average, there were 3.59 (SD = 1.83) children in the home. Among the Israeli Arab sample, 92% of the parents were married, 55–60% did not graduate from high school, and 43% reported their incomes as below the Israeli average (37% = average, 21% = above average). Parents reported that on average, there were 3.17 (SD = 1.39) children in the home. At Waves 2 and 3, 305 and 282 Israeli Jewish children and their parents were re-interviewed (resampling rates of 68% and 63% respectively). The decrement in the number of participants interviewed among Israeli Jews was mostly due to “refusals.” The refusing participants reported that they did not feel the monetary reimbursement was sufficient to justify their time. In fact, due to significant exchange rate changes, the amount of money offered to each participant was significantly less in waves 2 and 3. Because Israeli Arabs had much lower average incomes, the amount was perceived as sufficient by most of them. For Israeli Jews, t-tests revealed that attrition was generally not associated with the study variables, except that Israeli Jewish youth who were resampled reported higher levels of ethnic stereotypes (p < .05). At Waves 2 and 3, 386 and 385 Israeli Arab children and their parents were re-interviewed (resampling rates of 86% for both waves). For Israeli Arabs, attrition in Waves 2 and 3 was associated with exposure to ethno-political violence, such that Israeli Arabs who were resampled reported lower mean levels of exposure to ethno-political violence (p < .01).

Procedures

The research protocol for this study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan (Behavioral Sciences) and Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In both Palestine and Israel, potential participants were told that the study concerned the effects of ethno-political conflict on children and their families, assessments would take approximately one hour, and one parent and one child would be asked to participate. Written parent consent and child assent were obtained. The family was compensated $25 for the 1-hour interview. Interviews of the parent and child were conducted in the families’ homes separately and privately; interviewers read surveys to the respondents, who indicated answers that were then recorded by the interviewer. Interviewers worked in pairs, with one interviewing the parent and the other interviewing the child.

The study was conducted in three yearly waves of assessment. Although the timing of waves in Palestine and Israel were similar, they did not overlap precisely. Wave 1 was conducted from May 2007 through September 2007 in Palestine, and from May 2007 through October 2007 in Israel. Wave 2 was conducted from May 2008 through September 2008 in Palestine, and from May 2008 through December 2008 in Israel. Wave 3 was conducted from May 2009 through August 2009 in Palestine, and from May 2009 through April 2010 in Israel.

Measures

Demographic information

Parents and youth responded to standard questions to assess demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnic group, national group).

Negative stereotypes

Negative stereotypes, or negative beliefs about one's ethnic out-group, were assessed using a self-report measure designed to measure the degree to which individuals perceived ethnic out-groups as sentient humans. This 4-item Likert-type scale was developed based on existing measures of explicit ethnic stereotypes (Huesmann et al., 2012) and was modified for this sample by the research team, which included American, Israeli, and Palestinian scholars. This scale ranged from 0 (Not at all true of [out-group]) to 2 (Very true of [out-group]) with higher scores indicating more negative and dehumanized beliefs about ethnic out-groups (e.g., “How true is this of [ethnic out-group]... care about and love their family...feel sad if someone they love dies...are peaceful...are mean”). The ethnic out-group for Israeli Jewish youth was Palestinians, while the ethnic out-group for both Palestinian and Israeli Arab youth was Israeli Jews. These ethnic out-groups were chosen based on extant literature from this region which identifies the key ethnic distinction in the region as that between Jews and Arabs (e.g., Bar-Tal, 1996). For example, Landau et al. (2010) noted that because of the complex history of the Israeli-Palestinian and Israeli-Arab conflict, Israeli Arabs have a “sense of loyalty to their brethren” in the West Bank and Gaza, and that the “Jewish-Arab rift within Israel (is) the potentially most dangerous and violent internal social conflict in Israel” (p. 326). Coefficient alphas ranged from 0.69 to 0.79 across the three time points.

Exposure to ethno-political conflict and violence

The exposure to political conflict and violence scale was used to assess exposure to ethno-political conflict and violence at time 1 and includes 15 items adapted from Slone, Lobel, and Gilat (1999); αs = .86 self-report and .87 for parent report. Respondents indicated the extent to which the child experienced the event in the past year along a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = many times). The 15 items comprised three domains of political conflict and violence events: loss of, or injury to, a friend or family member (five items, α = .65 for parent report, α = .60 for self-report; e.g., “Has a friend or acquaintance of yours been injured as a result of political or military violence?”); experiencing security checks or threats (six items, α = .55 for parent report, α = .50 for self-report; e.g., “How often have you spent a prolonged period of time in a security shelter or under curfew?”); and witnessing actual violence (four items, α = .60 for parent report, α = .66 for self-report; e.g., “How often have you seen right in front of you [members of your ethnic group] being held hostage, tortured, or abused by [members of the opposing ethnic group]?”).

Parents of 8-year-olds reported on their children's exposure to ethno-political conflict and violence, whereas 11- and 14-year-old children provided self-reports of their exposure to ethno-political conflict and violence. This approach was utilized for the following reasons. First, our Institutional Review Board had concerns about the 8-year-olds’ emotional reactions to reporting on their exposure to this type of conflict and violence. Second, given the time constraints of the interviews with young children, parent reporting decreased the length of the interview for 8-year-olds. In a subsample of our youngest age cohort at Wave 3 (age: 10; N = 408), children's self-reports of exposure to ethno-political conflict and violence were significantly related to parents’ reports of the child's exposure (r = .68).

All measures were presented with no variation between waves of data collection. Measures were presented in appropriate native languages by region and ethnicity (Hebrew for Israeli Jews, Arabic for Palestinians, Hebrew or Arabic for Israeli Arabs). Original English measures were back-translated for accuracy by native-speaking research teams at the two data collection sites. Two rounds of pilot testing were conducted on our survey with nine parent–child dyads (three from each age group) in each region. The pilot testing included asking participants to discuss any items or response formatting that caused confusion. Item content and response formatting of the measures were found to be understandable across age groups in the pilot testing.

Data Analysis

We examined linear trajectories of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups across the three ethnic groups using multiple group analysis within a structural equation framework (McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003; Meredith & Tisak, 1990). Analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.11 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010). To investigate ethnic differences, we used multi-group procedures to test whether parameters differed by ethnicity. This involved testing the fit of a series of models in which we progressively constrained parameters to equality across ethnic groups (Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006). For each path, we started with a model in which we freely estimated all parameters within each group. We conducted a systematic and iterative process of constraining the parameters of the model to be equal across the three groups. If the constrained models did not provide a significantly worse fit to the data, as indexed by the change in the χ2 values between the two models, we concluded that the parameter did not significantly differ across the three ethnic groups. We then constrained the next most similar parameter to be equal across the three groups, using the same criteria. We repeated this procedure in testing for group differences in all parameter estimates. After arriving at the best fitting model, key time-invariant predictors (age, exposure to ethno-political violence) were included in the models when they increased the fit of the model. We report the fit statistics for the best fitting unconditional models, and the best fitting model including the time-invariant predictors.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for all major study variables in the full sample and by ethnic group. Table 2 presents bivariate correlations for all continuous study variables in the full sample (ethnic group differences are discussed in the context of the unconditional latent growth models). Mean levels of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups at each time point illustrate potential instability of stereotypes over time, as well as mean differences across ethnic groups. Further, as expected, exposure to ethno-political violence at time 1 is significantly correlated with negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups at all time points.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables

| Full Sample | Palestinian | Israeli Jewish | Israeli Arab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Exposure to ethno-political violence | 0.73 (0.47) | 1.07 (0.37) | 0.60 (0.36) | 0.39 (0.34) |

| Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T1 | 0.87 (0.53) | 0.98 (0.45) | 1.03 (0.57) | 0.57 (0.45) |

| Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T2 | 0.89 (0.59) | 0.99 (0.53) | 1.17 (0.58) | 0.51 (0.50) |

| Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T3 | 0.84 (0.63) | 1.05 (0.56) | 1.12 (0.59) | 0.35 (0.42) |

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Exposure to ethno-political violence | - | - | - | - |

| 2 Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T1 | 0.21** | - | - | |

| 3 Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T2 | 0.15** | 0.44** | - | - |

| 4 Negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups T3 | 0.25** | 0.38** | 0.46** | - |

p< .01

Ethnic Differences in Trajectories of Negative Stereotypes

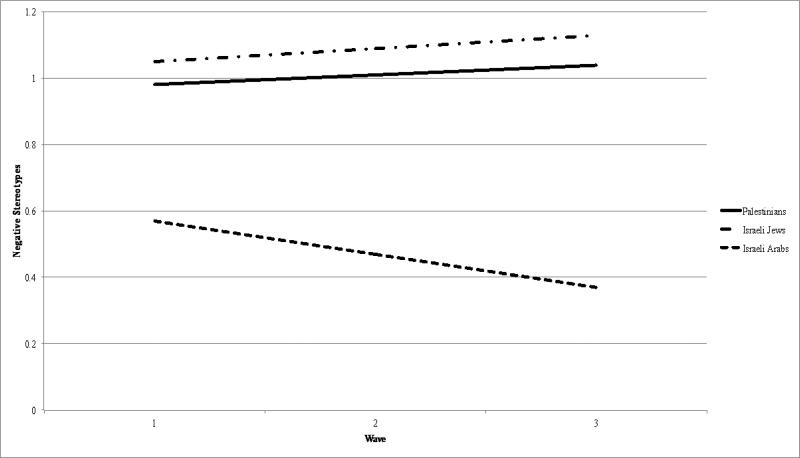

After a series of iterative tests to examine the appropriateness of constraining certain parameter estimates, the final, best-fitting model (Table 3) was one in which the slope variance was constrained across all three groups (Palestinian, Israeli Jewish, Israeli Arab), while all other parameters were allowed to be unconstrained across groups. This model retained 2 additional degrees of freedom and provided a better fit to the data compared to our baseline model which allowed all parameter estimates to vary freely across all groups, χ2(5) = 13.63, χ2/df = 2.73, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = .0.06 (.02, .10). In this model, there were significant ethnic differences at intercept, such that Israeli Arabs had significantly lower negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups and Israeli Jews had significantly higher negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups at Time 1. Palestinians’ starting point for negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups was significantly higher than that of Israeli Arabs, but significantly lower than that of Israeli Jewish youth. Both Palestinians and Israeli Jews showed significant increases in negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups over time, with Israeli Jews having a steeper incline of negative stereotypes. While these changes over time were significant, our parameter estimates illustrate that these increases over time were relatively small in comparison to Israeli Arabs who showed the opposite trend, a significant decline in negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups over time. See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of ethnic differences in the levels and changes over time in negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups.

Table 3.

Unstandardized Parameter Estimates (Standard Errors) of Unconditional Latent Growth Models of Negative Stereotypes of Ethnic Out-group by Ethnic Group

| Palestinians Est. (S.E.) | Israeli Jews Est. (S.E.) | Israeli Arabs Est. (S.E.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Means | |||

| Intercept | 0.98(0.02)*** | 1.05(0.03)*** | 0.57(0.02)*** |

| Slope | 0.03 (0.02)* | 0.04(0.02)* | −0.10(0.02)*** |

| Variance | |||

| Intercept | 0.08(0.02)*** | 0.16(0.03)*** | 0.11(0.02)*** |

| Slope | 0.03(0.01)*** | 0.03(0.01)*** | 0.03(0.01)*** |

| Correlation (I,S) | −0.02(0.01)+ | −0.01(0.01) | −0.06(0.01)*** |

| Model Fit | χ2(5) = 13.63, χ2/df = 2.73, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06 (.02, .10) | ||

Parameter estimates are presented for the final unconditional model.

p < .10

p< .05

p< .001

Figure 1.

Multi-Group Latent Growth Curve Model for Negative Stereotypes of Ethnic Out-Groups

Table 3 presents the results of the multi-group unconditional latent growth model for negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. The table provides estimates for means and variances for the latent intercepts and the latent slopes, as well as correlations between the latent intercepts and latent slopes. Fit statistics for the baseline and best-fitting final models, including chi-square values, chi-square by degrees of freedom ratios, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI) are reported in the text. Parameter estimates shown in the tables that differ across groups could not be constrained to equality without a significant decrement in model fit.

The Role of Age and Exposure to Ethno-Political Violence

Table 4 presents the results of the multi-group linear latent growth models of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups with the inclusion of two key time-invariant predictors – age and exposure to ethno-political violence. The final multi-group latent growth model for negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups in which we constrained slope variance while allowing all other parameter estimates to vary freely across the groups provided a marginally acceptable fit to the data. However, the model was further examined with the inclusion of time-invariant predictors that we hypothesized were key predictors of the development of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. Including both age (which accounts for potential age cohort effects), as well as exposure to ethno-political violence as time-invariant predictors helped to increase the fit of the final model. After a series of iterative tests to examine the appropriateness of constraining the parameter estimates of regressing age and exposure to ethno-political violence on the latent intercept and slope of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups, the best-fitting model was one in which all the parameters were unconstrained across groups. Thus, age and exposure to ethno-political violence were allowed to vary freely across the three ethnic groups as there were significant ethnic differences in the estimates of how they predicted both the latent intercept and slope of negative stereotypes. The final model retained 6 additional degrees of freedom and provided a better fit to the data, χ2(11) = 20.95, χ2/df = 1.90, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = .0.04 (.01, .07) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Unstandardized Parameter Estimates (Standard Errors) for Models of Age and Exposure to Ethno-political Violence Predicting Negative Stereotypes of Ethnic Out-group by Ethnic Group

| Palestinians Est. (S.E.) | Israeli Jews Est. (S.E.) | Israeli Arabs Est. (S.E.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age predicting | |||

| Intercept | −0.03 (0.01)*** | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.001 (0.01) |

| Slope | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.07 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.01)* |

| PEV predicting | |||

| Intercept | 0.08 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.06)*** |

| Slope | −0.10 (0.04)** | 0.04 (0.05) | −0.09(0.05)* |

| Model Fit | χ2(11) = 20.95, χ2/df = 1.90, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .04 (.01, .07) | ||

Note. N = 1499; PEV = Exposure to political and ethnic violence.

Parameter estimates are presented for the final predictive model.

p< .05

p ≤ .01

p< .001

As shown in Table 4, parameter estimates indicate significant ethnic differences in whether age and exposure to ethno-political violence predicts both the latent intercept and slope of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. Neither age nor exposure to ethno-political violence predicted the latent intercept or slope of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups for Israeli Jewish youth. This was not the case, however, for their Palestinian and Israeli Arab counterparts. In particular, our results indicate that age significantly predicted the latent intercept of ethnic stereotypes only for the Palestinian youth, such that older Palestinian youth had lower levels of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups at intercept (time 1) compared to their younger counterparts. Age positively predicted the latent slope in negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups, but only for Israeli Arabs. Thus, older Israeli Arab youth decline more steeply in their negative stereotypes than their younger peers.

Exposure to ethno-political violence also played an important role as a predictor for Palestinian and Israeli Arab youth. Specifically, exposure to ethno-political violence was positively associated with the latent intercept of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. In other words, Israeli Arabs who were exposed to higher levels of ethno-political violence had higher negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups at time 1. Interestingly, higher exposure to ethno-political violence was negatively associated with the latent slope of negative stereotypes for both Palestinians and Israeli Arabs. Palestinians who were exposed to higher ethno-political violence had a slower rate of increase in their negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups, while Israeli Arabs who were exposed to higher ethno-political violence had a slower rate of decline in their negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups.

Discussion

In this study, we examined changes over three years in negative and dehumanizing stereotypes of ethnic out-groups among Israeli Jewish, Israeli Arab, and Palestinian youth, as well as the role of age and exposure to ethno-political violence as covariates of those trajectories. We hypothesized that negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups would increase as youth got older. Based on the nature of the conflict and extant literature, we expected that Palestinians and Israeli Jews would have higher levels and steeper increases over time than Israeli Arabs. We also expected that age and exposure to ethno-political violence would be positively associated with higher levels and steeper increases in negative stereotypes.

Our findings offer partial support for our hypotheses and highlight the developmental shifts that occur in negative and dehumanizing beliefs about ethnic out-groups during middle childhood and adolescence. At the same time, these findings support Bronfenbrenner's (1979) assertion that how ethnicity is constructed in macro-contexts (e.g., through ethno-political violence) has critical implications for individual developmental processes, in this case in the development of negative stereotypes. In particular, the results of this investigation offer insight into how we view contexts of prolonged ethno-political conflict and how such experiences ultimately shape youths’ beliefs about others.

Ethnic Differences in the Development of Negative Stereotypes

Developmental patterns of negative and dehumanizing stereotypes about ethnic out-groups highlight how context shapes individual developmental processes. First, Israeli Jewish youth reported the highest levels of negative stereotypes at time 1, followed by Palestinian youth, whereas Israeli Arabs reported the lowest levels of negative stereotypes. As expected, both Israeli Jews and Palestinians showed increases over time in negative stereotypes, with Israeli Jews having slightly steeper inclines in these stereotypes. The high levels and inclines in negative stereotypes for Israeli Jewish and Palestinian youth mirrors our expectations that youth will increasingly see members of ethnic out-groups negatively, particularly in a context of ethno-political conflict. This might be due to the fact that ethno-political violence exacerbates perceptions of in- versus out-groups (Bar-Tal, 2004; Dixon, 2008; Dubow et al., 2009; Huesmann et al., 2012; Mackie et al., 1996). While both groups display significant increases over time, they are at a low rate which indicates the slow but steady process by which youth growing up in contexts of ethno-political violence come to see the “other” in more negative ways and as less human.

Surprisingly, Israeli Arabs showed the opposite pattern, displaying decreases over time in negative stereotypes. These findings suggest that, despite increasing social-cognitive abilities, Israeli Arab youth did not develop increasingly negative stereotypes of Israeli Jews over time. This key difference, which is particularly stark when compared to Palestinians with whom they share an ethnicity, sheds light on the critical role of context in shaping the development of individual perceptions (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Such differences in context are evident from both a macro-level, such as the institutional distinctions that Israeli citizenship bears, to the micro-level, such as the opportunity to interact with Israeli Jews. Our findings might reflect such contextual differences in the experiences of different ethnic groups. For example, whereas Israeli Arabs often report feeling segregated from aspects of Israeli society (Moore & Guy, 2012), they have contact with Israeli Jews in everyday activities (such as shopping, going to school). The role of contact between groups has often been touted as a “panacea” for prejudice and discrimination (Hewstone, 1990). Being witness to such activities might allow Israeli Arabs to separate acts of discrimination or ethno-political violence from the capacity of Israeli Jews to simply be human. This might be less possible, however, for Palestinians who mainly interact with Israeli Jews in military uniform, such as at checkpoints.

Another possible explanation for our findings with Israeli Arabs is that, despite inequality in Israeli society (see Moore & Guy, 2012), Israeli Arabs share citizenship with Israeli Jews and therefore include their Israeli nationality as an aspect of their personal identity (Moore & Guy, 2012). In fact, scholars have noted the struggle that Israeli Arabs face in identifying both as Arab and as Israeli (Moore & Guy, 2012; Shikaki, 1999; Shtendal, 1992). In this situation, the lines between in-group and out-group are blurred, which might make it more difficult for Israeli Arabs to roundly view Israeli Jews in purely negative ways and as less human.

Age and Exposure to Ethno-Political Violence

Age is a key component of our developmental model, as social-cognitive development more broadly forms the foundation for why we expect youth to exhibit changes over time in negative and dehumanizing stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. Based on that assumption, we hypothesized that perceptions and developmental patterns of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups should be heightened based on the age of the participants. Surprisingly, our findings indicate that there does not appear to be an overall impact of age on either the intercept or slope of negative stereotypes.

While age did not uniformly influence the levels or change over time in negative stereotypes, interesting ethnic differences emerged. First, age had no influence on the intercept or slope of negative stereotypes for Israeli Jews. This finding might be an artifact of the overwhelming sense of the existential threat to Israel as a homeland for Jews (Dor, 2004; Feldman, 2002). This heightened sense of threat might act to intensify messages and perceptions about the “other” (Bar-Tal, 2004), particularly for Israeli Jews (Bar-Tal, 1996).

While age was not a significant predictor for Israeli Jews, this was not the case for the Palestinian youth in our sample. Contrary to our expectations, we found that older Palestinians had lower negative stereotypes at Time 1. This finding may reflect that older Palestinians might have a more complex understanding of the conflict and, therefore, might be more likely to distinguish between actions of the Israeli government and military and the intentions of Israeli Jewish citizens. In other words, the social-cognitive capacity that allows Palestinian youth to increasingly perceive stereotypes overall might simultaneously allow them to understand and see beyond the complexities that undergird such differences. Age also played a different role for older Israeli Arabs who declined more steeply in their negative stereotypes of Israeli Jews. It is possible that this finding might reflect the growing tension that they feel between identifying as both Israeli and Arab (Moore & Guy, 2012; Shikaki, 1999; Shtendal, 1992). In other words, decreases in negative stereotypes might be intensified as Israeli Arabs develop more nuanced identities over time (Erikson, 1968).

Beyond age, ethno-political violence shapes the present experiences of Israeli and Palestinian youth, while creating the foundation for the cultural forces that inform their development. We hypothesized that exposure to ethno-political violence would heighten negative and dehumanizing perceptions of ethnic out-groups by exacerbating the distinctions between in- and out-groups (Bar-Tal, 2004; Dixon, 2008; Stangor & Schaller, 1996). Our findings, however, surprised us by illustrating that exposure to ethno-political violence does not uniformly exacerbate the levels and slopes of negative stereotypes across ethnic groups.

As with age, ethnic differences emerged in the role that ethno-political violence plays in the intercepts and slopes of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups. In line with our hypotheses, Israeli Arab youth who were exposed to more ethno-political violence had higher negative stereotypes of Israeli Jews at Time 1. But surprisingly, Palestinian youth who were exposed to higher levels of ethno-political violence displayed less steep increases in negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups, while Israeli Arab youth who were exposed to higher levels of ethno-political violence displayed less steep declines in negative stereotypes of Israeli Jews. Although speculative, perhaps exposure to ethno-political violence might have the unexpected impact of promoting more complex thinking. For example, youth might increasingly reconcile the reality of ethno-political conflict between Israeli Jews and Palestinians while recognizing that such tensions might not reflect on the underlying humanity of Israeli Jewish citizens. This could be particularly true for Palestinians and Israeli Arabs, who experience clearer social differentiation between “official” actions and average citizens, compared to Israeli Jews. This finding also might illustrate post-traumatic growth, or the capacity to show positive changes in functioning beyond merely coping (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995), even in a context of ethno-political violence.

As with age, exposure to ethno-political violence had no influence on the level or patterns of negative stereotypes for Israeli Jewish youth. Thus, Israeli Jews consistently displayed high and increasing negative stereotypes of Palestinians. Exposure to ethno-political violence might have no impact on the latent intercept or slope of negative stereotypes of Israeli Jews due to a number of differences in their experiences. First, Israeli Jews are exposed to less ethno-political violence overall than Palestinians and Israeli Arabs (Boxer et al., 2013). Second, Israeli political control affects the social and economic trends and daily life of Palestinians (Ugland & Tamari, 1993), while Palestinians do not have equivalent political control over Israeli Jews (Moore & Guy, 2012). Third, Israeli Jewish identity is framed around the perception that Israel is engaged in an existential battle (Dor, 2004; Feldman, 2002), whereas Palestinian identity is centered around political resistance (Barber & Olsen, 2009). Thus, perceptions of threat to the mere existence of Israel by Palestinians (Bar-Tal, 2004; Dor, 2004; Feldman, 2002) might heighten the need for Israelis to justify their acts and differentiate between themselves and Palestinians (Bar-Tal, 1996, 2004; Bar-Tal & Teichman, 2005).

Overall, increases in negative stereotypes about ethnic out-groups by both Israeli Jews and Palestinians gives credence to the development of delegitimizing beliefs, or the process of attributing extremely negative characteristics to out-groups with the purpose of denying their humanity. As noted earlier, delegitimizing beliefs might serve to explain the conflict, justify aggression against the out-group, and provide in-group members with a sense of superiority (Bandura, 2002; Bar-Tal, 2000; Haslam, 2006).

Limitations and Implications

This longitudinal study offers a number of important contributions, but is also marked by key limitations. First, our data on negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups and exposure to ethno-political violence are based on child- and parent-report. Although this method allows the opportunity to assess perceptions of lived experience, it may also be limited by the reporters’ ability to recall events and their biases in such recollections. Despite this limitation, self-reports may be optimal in the context of understanding individual perceptions. Future studies should include other indicators of negative stereotypes of ethnic out-groups, as well as stereotypes of one's in-group to frame how perceptions of the self and other are interrelated (Huesmann et al., 2012). Second, we recognize that integrating parent- and child-reports of exposure to ethno-political violence may not be optimal, although reporter bias did not appear to affect our data (see also Dubow et al., 2009). Future studies should utilize multiple converging sources of information, perhaps including place-based indicators, regarding exposure to violence (Boxer, Sloan-Power, Schappell, & Piza, in press).

Despite the emergence of important ethnic differences in the intercepts and slopes of negative stereotypes, it is important to not assume homogeneity in the beliefs of Palestinians, Israeli Arabs, and Israeli Jews (Moore & Guy, 2012). While they share similar experiences and cultural narratives, there is a wide range of variation in individual experiences. Including age and ethno-political violence in our models, however, offers new insight into what may account for variability in these trajectories. Future studies should examine intra-group variations in these developmental processes. Further, while the ethnic differences found in this study are unique to the Israel-Palestine conflict, our findings also offer a perspective that may be meaningful for any youth who are growing up surrounded by ethno-political violence. Specifically, when youth are exposed to prolonged ethno-political violence, it shapes how those youth not only come to see themselves, but how they view the “other.”

Practically speaking, our study contributes three lessons that may be useful for how we structure and implement interventions for youth growing up besieged by ethno-political conflict. First, youth are aware of stereotypes and the value assigned to different ethnic groups both in their micro- and macro-contexts. In order to address the development of perceptions of the “other,” youth would benefit from frank discussions about ethnic groups and their linked stereotypes. Second, adolescents display normative social-cognitive development, which allows them to not only comprehend (and sometimes endorse) negative stereotypes of others, but to also unpack complexities and contradictions in those stereotypes. Future interventions would benefit from actively fostering resistance to stereotypes and resilience from exposure to ethno-political violence. Finally, opportunities for authentic interactions with the “other” can create a framework for teaching youth the shared humanity among us all.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD047814; L.R. Huesmann, PI).

The lead author, Erika Y. Niwa, was affiliated with Rutgers University at the time that this paper was written, but is now affiliated with the Department of Psychology at the City University of New York's Brooklyn College.

Contributor Information

Erika Y. Niwa, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University (see acknowledgements for additional information regarding current academic affiliation)

Paul Boxer, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University; Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Eric F. Dubow, Department of Psychology, Bowling Green State University; Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan

L. Rowell Huesmann, Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Simha Landau, Institute of Criminology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Department of Criminology, Emek Yezreel Academic College.

Khalil Shikaki, Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research.

Shira Dvir Gvirsman, Department of Communication, Netanya Academic College.

References

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Perseus Books; Cambridge, MA: 1954/1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education. 2002;31:101–119. doi:10.1080/030572402201322. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Glimpsing the complexity of youth and political violence. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and War: How Youth Deal with Political Violence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 3–32. Ch. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Positive and negative psychosocial functioning after political conflict: Examining adolescents of the first Palestinian Intifada. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and War: How Youth Deal with Political Violence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 207–237. Ch. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. Development of social categories and stereotypes in early childhood: The case of “the Arab” concept formation, stereotype, and attitudes by Jewish children in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1996;20(3/4):341–370. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00023-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. Shared Beliefs in a Society: Social Psychological Analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. The necessity of observing real life situations: Palestinian-Israeli violence as a laboratory for learning about social behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2004;34:677–701. doi:10.1002/ejsp.224. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D, Raviv A, Raviv A, Dgani-Hirsh A. The influence of the ethos of conflict on Israeli Jews’ interpretation of Jewish-Palestinian encounters. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2009;53(1):94–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D, Teichman Y. Stereotypes and prejudice in conflict: Representations of Arabs in Israeli Jewish society. Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Landau SF, Gvirmsman SD, Shikaki K, Ginges J. Exposure to violence across the social ecosystem and the development of aggression: A test of ecological theory in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Child Development. 2013;84(1):163–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01848.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Sloan-Power E, Schappell A, Piza E. Using Police Data to Measure Children's Exposure to Neighborhood Violence: A New Method for Evaluating Relations between Exposure and Mental Health. To appear in Violence and Victims. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00155. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, Brown RJ. Intergroup relations. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill; Boston, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in children's adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Testing a social ecological model for relations between political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:405–418. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000143. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cremer D. Relations of self-esteeem concerns, group identification and self-stereotyping to in-group favoritism. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;141(3):389–400. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon TL. Network news and racial beliefs: Exploring the connection between national television news exposure and stereotypical perceptions of African Americans. Journal of Communication. 2008;58:321–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00387.x. [Google Scholar]

- Dor D. Intifada hits the headlines. Indiana University Press; Bloomington: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P. A social-cognitive framework for understanding the impact of exposure to persistent ethno-political violence on children's psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 2009;12:113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0050-7. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P, Landau S, Dvir S, Shikaki K, Ginges J. Exposure to political conflict and violence and posttraumatic stress in Middle East youth: Protective factors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012a;41(4):402–416. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.684274. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.684274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Landau S, Dvir S, Shikaki K, Ginges J. Cumulative effects of exposure to violence on posttraumatic stress in Palestinian and Israeli youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012b;41(6):837–844. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.675571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W. Norton & Company; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S. Managing the conflict with the Palestinians: Israeli's strategic options. Strategic Assessment. 2002;5(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social cognition. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Waski BH, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR. A cognitive-ecological model of aggression. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale. 2004;17:177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N. Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10(3):252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M. The ‘ultimate attribution error’? A review of the literature on intergroup causal attribution. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;20:311–335. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. The role of social information processing and cognitive schemas in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein E, editors. Human aggression: Theories, research, and implications for policy. Academic Press; New York: 1998. pp. 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Boxer P, Souweidane V, Ginges J. Foreign wars and domestic prejudice: How media exposure to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict predicts ethnic stereotyping by Jewish and Arab American Adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22(3):556–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00785.x. doi:0.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyens J, Yzerbyt VY, Schadron G. Stereotypes and Social Cognition. Sage; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie DM, Hamilton DL, Susskind J, Rosselli F. Social psychological foundations of stereotype formation. In: Macrae CN, Stagnor C, Hewstone M, editors. Stereotypes and stereotyping. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 41–78. Ch. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O'Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Zajonc RB. The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Random House; New York: 1985. pp. 137–230. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Growth curve analysis in contemporary psychological research. In: Schinka J, Velicer W, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2003. pp. 447–480. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Tisak J. Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika. 1990;55:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Moane G. Bridging the personal and the political: Practices for a liberation psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1-2):91–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1023026704576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D, Guy A. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict: The socio-historical context and the identities it creates. In: Landis D, Albert RD, editors. Handbook of Ethnic Conflict. Springer; US: 2012. pp. 199–240. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide. Sixth edition. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niwa EY. Ethnic-racial discrimination from adults and peers and its psychological and social correlates during early adolescence: A mixed-method, longitudinal examination. 2012 (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Oren N, Bar-Tal D. The detrimental dynamics of delegitimization in intractable conflicts: The Israeli-Palestinian case. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2007;31(1):111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Ramallah [June 25, 2013];Census final results in the West Bank: Summary (Population and Housing) 2008 Aug; from http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1487.pdf.

- Peguero AA. Victimizing the children of immigrants: Latino and Asian American student victimization. Youth & Society. 2009;41(2):186–208. doi:10.1177/0044118X09333646. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Castaneda-English P, Ybarra VC. Role of perspective-taking ability and ethnic socialization in the development of adolescent ethnic identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:161–184. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0902_3. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, Struch N. Values, stereotypes, and intergroup antagonism. In: Bar Tal D, Grauman CF, Kruglanski A, Stroebe W, editors. Stereotyping and Prejudice: Changing Conceptions. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shikaki H. Beyond democracy in Palestine: The peace process, national rehabilitation and elections. In: Manna A, editor. The Palestinians in the Twentieth Century: An Inside Look. The Cener for the Study of Arab Society in Israel (Hebrew); Haifa: 1999. pp. 63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shtendal U. Israeli Arabs – Between the Rock and the Hard Place. Academon, The Hebrew University; Jerusalem: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Slone M, Lobel T, Gilat I. Dimensions of the political environment affecting children's mental health. The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 1999;43:78–91. doi:10.1177/0022002799043001005. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartmann T. A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST); A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:817–833. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001454. doi:10.1017/S0954579497001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangor C, Schaller M. Stereotypes as individual and collective representations. In: Macrae CN, Stagnor C, Hewstone M, editors. Stereotypes and stereotyping. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1996. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Forgas JP. Social categorization: Cognitions, values, and groups. In: Stangor C, editor. Stereotypes and Prejudice: Essential Readings. Psychology Press; New York: 2000. pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research, Tel-Aviv University The Peace Index Project. 2000 Nov; Retrieved from http://www.tau.ac.il/peace (in Hebrew)

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and Transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ugland O, Tamari S. Aspects of Social Stratification. In: Heiberg M, Ovensen G, editors. Palestinian Society. FAFO; Oslo: 1993. pp. 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . The state of the world's children – Children in War. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Way N, Santos C, Niwa EY, Kim-Gervey C. To be or not to be: A contextualized understanding of ethnic identity development. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;120:61–79. doi: 10.1002/cd.216. Summer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]