The worst form of inequality is to try to make unequal things equal.

— Aristotle

Biomedical research of human disease in the United States has focused predominantly on populations of European descent (1–3). These findings are frequently used to inform disease risk, progression, and treatment for other racial/ethnic groups. Implicit in this approach is the assumption that racial/ethnic groups have similar disease etiology or burden. Generalizing results from research performed in one racial/ethnic group to another can work reasonably well, or it can have fatal consequences (4, 5). The lack of diversity in large-scale biomedical studies hinders our understanding of human disease and severely limits our ability to develop optimal therapeutic interventions and treatments.

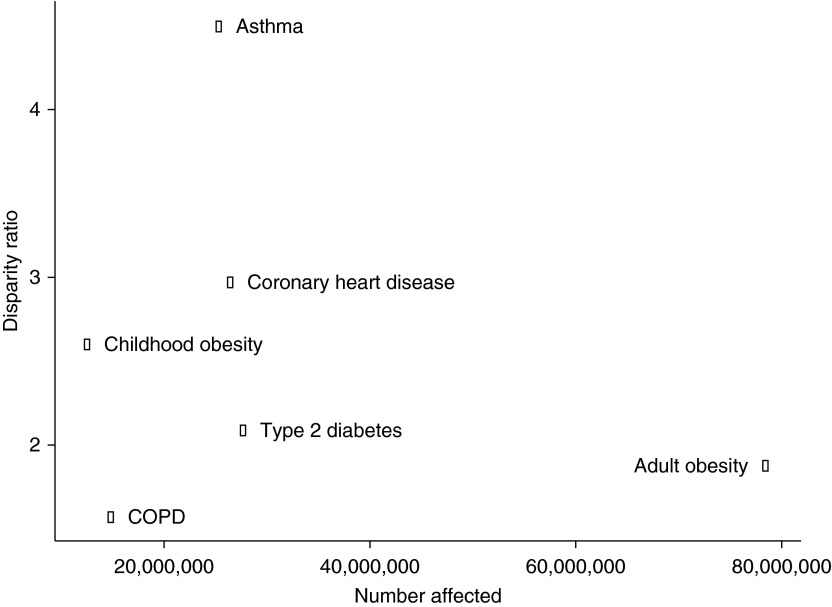

This fact is strikingly apparent in the context of asthma, the most common chronic disease among children, which affects more than 330 million people worldwide (6). Asthma is the most disparate health condition among common diseases in the United States (Figure 1). Asthma mortality is fourfold higher in Puerto Ricans and African Americans than in European Americans (7). A similar but attenuated trend is observed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), where prevalence is highest among Puerto Ricans and lowest among Mexican Americans (8). Clearly, pulmonary diseases such as asthma and COPD are affected by social, cultural, and genetic factors that vary across populations.

Figure 1.

Asthma is the most racially disparate common disease. Selected common diseases are plotted along the x-axis according to the number of people afflicted in the United States. The disparity ratio represents the ratio of the highest and lowest prevalence (or incidence) observed for a given disease across race/ethnicity. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The proportion of Latinos represented in National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded pulmonary disease studies has grown by more than fivefold since the passage of the NIH Revitalization Act in 1993, but still represented less than 2% of NIH-funded respiratory studies in 2013 (3). To address the lack of large, well-designed studies to assess the health of Latinos, in 2006, the NIH made a bold and ambitious move by funding the Hispanic Community Health Study (HCHS)/Study of Latinos (SOL). HCHS/SOL is a multicenter epidemiological study of more than 16,400 Hispanic/Latino adults designed to describe the prevalence and protective or harmful factors of selected chronic diseases, including pulmonary conditions such as asthma and COPD; in essence, to document the health of Latinos in the United States.

In this issue of the Journal, Barr and colleagues (pp. 386–395) leverage the large-scale census-based sampling of HCHS/SOL and report on significant and consistent differences in lifetime and current asthma prevalence between Latino subgroups (9). In this definitive study of asthma among Latinos, the authors report that current asthma was most prevalent among Puerto Ricans (15.3%), intermediate among Cubans (8.6%) and Dominicans (6.7%), and least prevalent among Mexicans (3.4%). The variation in lifetime prevalence is even more striking: Puerto Ricans, 36.5%; Cubans, 21.8%; Dominicans, 15.4%; Central Americans, 11.2%; and Mexicans, 3.4%. In MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis), which used a different sampling methodology, lifetime asthma prevalence estimates were 13.0% for African Americans and 12.1% for whites (9). Differences in COPD prevalence also varied significantly between Latino subgroups, but asthma and tobacco smoking explained this. The authors also found that asthma was more prevalent among Latinos born in the mainland United States and those who had moved to the United States as children compared with those who were born abroad.

Asthma prevalence was consistently highest among Puerto Ricans, regardless of place of birth or age of migration. This observation is consistent with the concept that asthma is a product of a complex interaction between environmental and genetic factors. Moreover, the distribution of these factors varies between and within racial/ethnic groups. The unique characteristics about the island of Puerto Rico and the high asthma prevalence relative to other Hispanic Caribbean countries present a scientific opportunity to better understand gene–environment interactions for asthma and merit further investigation.

The obvious strength of this study is the large and well-characterized HCHS/SOL cohort and the authors’ incorporation of clinical, demographic, and sociocultural data to obtain and compare asthma and COPD prevalence within and between Latino subgroups. Never before has a study of this size, quality, and scope been performed with such granularity. The authors have efficiently and definitively addressed several inconsistencies concerning asthma and COPD prevalence within the Latino/Hispanic population. Previous findings from smaller studies, such as the higher prevalence of asthma in Puerto Ricans and the contrasting low prevalence in Mexicans (10), were confirmed and further characterized across several Latino subgroups to provide a more complete picture of asthma prevalence within the larger Latino population. This study also addresses the question of varying COPD prevalence among Latinos and suggests that the variations reported in smaller studies were likely driven by differences in tobacco exposure and asthma history.

Analyses integrating diverse populations have been rare, although the pulmonary field has been on the forefront. The NHLBI-sponsored EVE Asthma Genetics Consortium was assembled around this idea in 2009. Current NIH-funded initiatives moving toward precision medicine in all populations have made diversity a priority, including the NHLBI-funded Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine and National Human Genome Research Institute-funded Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology studies. The proposed Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program promises to be truly transformational in this regard, standing up a national research cohort of 1 million or more U.S. volunteers, representing the rich diversity of the United States (11). Not only will studies similar to these provide a more comprehensive understanding of biomedicine, but ethnically diverse studies will likely result in increased buy-in from communities feeling historically marginalized.

There are dramatic demographic shifts occurring in the United States: For the first time, racial/ethnic minorities make up more than half of all the children born in the United States, of which Latinos are the largest and fastest growing group. These facts have significant medical, public health, economic, and political implications. However, the biomedical community has largely adopted the classification and study of Latinos as a single homogenous racial/ethnic group. The results from HCHS/SOL, along with previous studies, provide strong support that environmental and genetic factors for asthma differ by race/ethnicity. The changing U.S. demographics further underscore the significant disease burden asthma carries for the nation, as well as the need to investigate the etiology of the disease in patient cohorts that are more representative of the current, and future, U.S. population.

President Obama made history by announcing the Precision Medicine Initiative during his State of the Union address (12). He proposed a revolutionary shift in patient care that highlighted the necessity of promoting research considering social, environmental, and genetic factors to ensure that all individuals receive the right diagnoses and treatments at the right time. The recognition that many patterns of disease risk are population-specific, and in the case of U.S. Latinos, ethnic-specific, presents a significant gain in our knowledge of complex disease. This recognition is likely to be mirrored by an increase in targeted therapies as the growing biotech industry recognizes the “untapped” market potential of tailored therapies. Applied correctly, the Precision Medicine Initiative edict encourages the application of medical care and research efforts in a socially just manner, such that the rising tide of precision medicine lifts all boats, including groups disproportionately affected by disease. The study by Barr and colleagues is a step in the right direction.

Footnotes

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bustamante CD, Burchard EG, De la Vega FM. Genomics for the world. Nature. 2011;475:163–165. doi: 10.1038/475163a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen MS, Jr, Lara PN, Dang JHT, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual: renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2014;120:1091–1096. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burchard EG, Oh SS, Foreman MG, Celedón JC. Moving toward true inclusion of racial/ethnic minorities in federally funded studies: a key step for achieving respiratory health equality in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:514–521. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1944PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasan MS, Basri HB, Hin LP, Stanslas J. Genetic polymorphisms and drug interactions leading to clopidogrel resistance: why the Asian population requires special attention. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123:143–154. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.744308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P, Lin J-J, Lu C-S, Ong C-T, Hsieh PF, Yang C-C, Tai C-T, Wu S-L, Lu C-H, Hsu Y-C, et al. Taiwan SJS Consortium. Carbamazepine-induced toxic effects and HLA-B*1502 screening in Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1126–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Asthma Network The global asthma report 2014 Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network; 2014. [accessed 2015 Oct 17]. Available from: http://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. Health, United States, 2010: with special feature on death and dying. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akinbami LJ, Liu X. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998-2009. NCHS Data Brief. 2011:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr RG, Avilés-Santa L, Davis SM, Aldrich TK, Gonzalez F, II, Henderson AG, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Liu K, Loredo JS, et al. Pulmonary disease and age at immigration among Hispanics: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016193386–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117:43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program: building a research foundation for 21st century medicine [accessed 2015 Oct 16]. Available from: http://acd.od.nih.gov/reports/DRAFT-PMI-WG-Report-9-11-2015-508.pdf

- 12.Remarks by the President in State of the Union Address. Washington, DC: The White House; 2015 [accessed 2015 Sept 15]. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/20/remarks-president-state-union-address-january-20-2015