UpToDate search activity is useful for detecting and monitoring outbreaks of Middle East respiratory syndrome in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords: digital disease detection, epidemic intelligence, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), UpToDate

Abstract

Background. UpToDate is an online clinical decision support resource that is used extensively by clinicians around the world. Digital surveillance techniques have shown promise to aid with the detection and monitoring of infectious disease outbreaks. We sought to determine whether UpToDate searches for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) could be used to detect and monitor MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia.

Methods. We analyzed daily searches related to MERS in Jeddah and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia during 3 outbreaks in these cities in 2014 and 2015 and compared them with reported cases during the same periods. We also compared UpToDate MERS searches in the affected cities to those in a composite of 4 negative control cities for the 2 outbreaks in 2014.

Results. UpToDate MERS searches during all 3 MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia showed a correlation to reported cases. In addition, UpToDate MERS search volume in Jeddah and Riyadh during the outbreak periods in 2014 was significantly higher than the concurrent search volume in the 4 negative control cities. In contrast, during the baseline periods, there was no difference between UpToDate searches for MERS in the affected cities compared with the negative control cities.

Conclusions. UpToDate search activity seems to be useful for detecting and monitoring outbreaks of MERS in Saudi Arabia.

Digital surveillance techniques have shown promise for aiding with the detection and monitoring of infectious disease outbreaks [1–6]. UpToDate is an online clinical decision support resource that is used extensively by clinicians worldwide. Analysis of UpToDate search data showed a strong correlation with influenza activity in the United States [3] and was also useful for monitoring drug safety [7, 8]. The extent to which UpToDate search data could be useful for monitoring infectious disease outbreaks in different regions of the world is unknown.

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) can cause severe and sometimes fatal pneumonia. It emerged in 2012 in Jordan and Saudi Arabia and has subsequently caused both sporadic cases and outbreaks. As of late January 2016, >1630 cases of MERS-CoV infection and >580 associated deaths had been reported worldwide, mostly in Saudi Arabia [9, 10].

There was a sharp increase in MERS cases in the spring of 2014 in Saudi Arabia, due largely to hospital-based outbreaks in Jeddah and Riyadh. These cases have been reported, which allowed us to compare UpToDate search query data with reported cases. The Jeddah outbreak in 2014 involved 255 patients [11], the Riyadh outbreak in 2014 involved 45 patients [12], and the Riyadh outbreak in 2015 involved 171 patients [13]. The Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia has provided access to UpToDate to all individuals in Saudi Arabia since January 1, 2014. As a result, UpToDate is used widely in Saudi Arabia. This has provided us with an opportunity to assess whether UpToDate search queries are able to detect MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia.

METHODS

We counted the number of daily searches that were related to MERS in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia from January 1, 2014 to May 16, 2014 and compared them with reported cases during the same period [11]. We also counted the number of daily searches related to MERS in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between March 29, 2014 and May 21, 2014 and compared them with reported cases during the same period [12]. These date ranges were chosen to correspond to the dates reported in published articles. For the outbreak in Jeddah in 2014, for symptomatic cases (191 of 255 cases; 75%), the date given for each case represents the date of onset of illness; for asymptomatic cases (64 of 255 cases; 25%), the date given represents the date of the test for MERS-CoV [11]. For the outbreak in Riyadh in 2014, for symptomatic cases (41 of 45 cases; 91%), the date given for each case represents the date of onset of illness; for asymptomatic cases (4 of 45 cases; 9%), the date given represents the date of virus detection [12]. In addition, we counted weekly searches related to MERS in Riyadh from June 20, 2015 to October 3, 2015 and compared them with cases reported by the World Health Organization [13]. We considered relevant search terms to be those related to MERS, coronaviruses, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or mechanical ventilation.

For the 2 outbreaks in 2014, we compared the results graphically by showing the 7-day rolling mean for the number of UpToDate MERS searches together with the 7-day rolling mean for the number of reported cases. The 7-day rolling mean for the date of interest was determined by calculating the average of the sum of the daily case counts for the date of interest and for 3 days before and 3 days after the date of interest. In contrast to the analyses of the earlier outbreaks, for the 2015 outbreak in Riyadh, we reported weekly cases and did not calculate the 7-day rolling mean because we only had access to weekly data for reported cases. We calculated the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for each daily (Figures 1 and 2) or weekly (Figure 3) comparison of UpToDate MERS searches to reported cases.

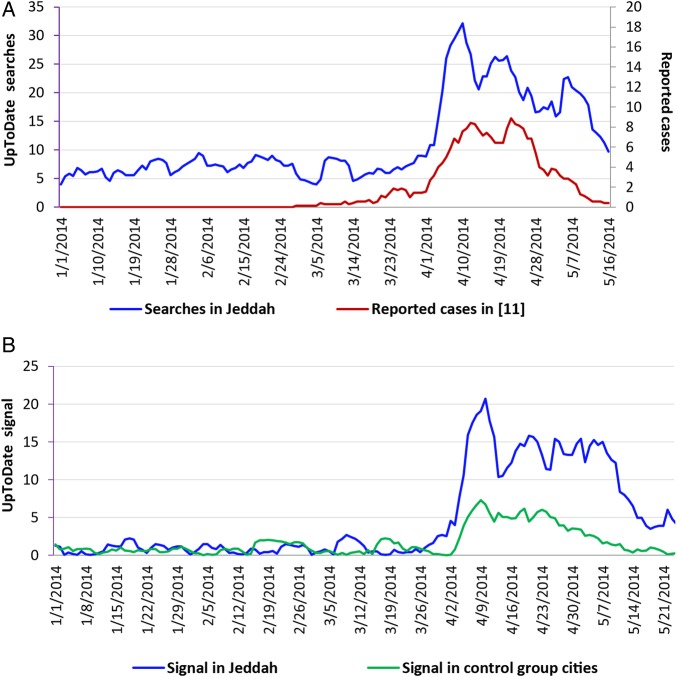

Figure 1.

Number of UpToDate Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) searches compared with number of reported cases in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (7-day rolling means for each) from January 1, 2014 through May 16, 2014 (A). UpToDate MERS signals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia and in the composite of 4 control cities in Saudi Arabia, January 1, 2014 through May 21, 2014 (B).

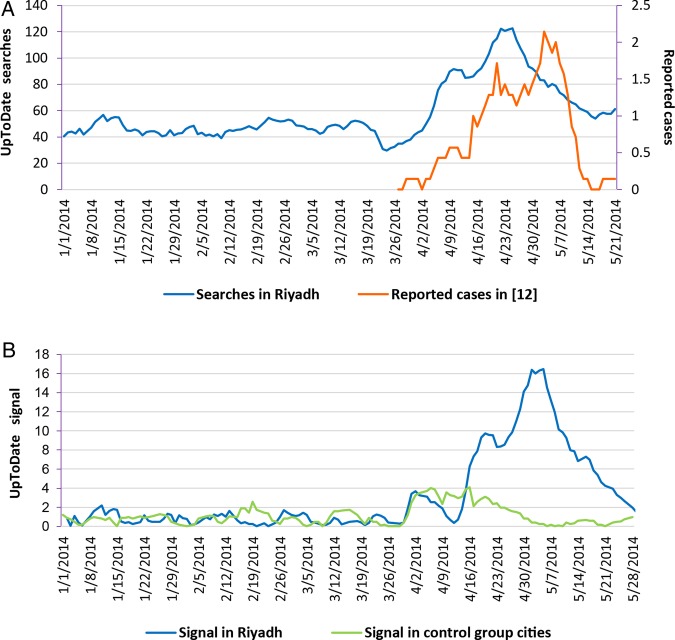

Figure 2.

Number of UpToDate Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) searches in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from January 1, 2014 through May 21, 2014 compared with the number of reported cases (7-day rolling means for each) from March 29, 2014 through May 21, 2014 (A). UpToDate MERS signals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and in the composite of 4 control cities in Saudi Arabia, January 1, 2014 through May 28, 2014 (B).

Figure 3.

Number of UpToDate Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) searches in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from June 20, 2015 through October 3, 2015 compared with the number of reported cases per week in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia during the same period.

For a control group, we analyzed UpToDate searches in 4 control cities in Saudi Arabia that were not having MERS outbreaks at the time that the Jeddah and Riyadh outbreaks were occurring in 2014; the control cities were Abha, Buraydah, Medina, and Tabuk. We selected these cities to be the 4 control cities because they did not have MERS outbreaks at the time of 2014 outbreaks in Jeddah and Riyadh and because the combined search volume of UpToDate searches in these cities was similar to the search volume in Jeddah during the same period. To establish a baseline for the Jeddah and Riyadh outbreaks in 2014, data were selected from January 1, 2014 to February 28, 2014 (considered an outbreak-free period). We calculated the mean and standard deviation for the baseline periods.

We used the following formula to calculate the signal (increased UpToDate MERS search activity in terms of number of fold increase over the standard deviation) for both the study groups and the control group:

Daily Searches indicate UpToDate daily MERS searches during the outbreak period; AVGbaseline indicates the average of UpToDate MERS searches during the baseline period; and σbaseline indicates the standard deviation of UpToDate MERS searches during the baseline period.

The Student's unpaired t test was used to compare the UpToDate MERS signals in Jeddah and Riyadh during the 2014 outbreaks with the signal in the composite of the 4 negative control cities. A P value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

To provide background information about overall UpToDate search volume in Jeddah and Riyadh, we calculated the average number of daily UpToDate searches (for the 2 outbreaks in 2014) or weekly UpToDate searches (for the outbreak in 2015) in the relevant city both before and during the outbreak period of interest.

RESULTS

During the outbreak period in 2014, UpToDate MERS searches in Jeddah showed a correlation to the reported MERS cases; the correlation coefficient was 0.886 (P < .00001) (Figure 1A). In addition, UpToDate MERS searches in Jeddah during the outbreak period were significantly higher than those in the composite of the 4 negative control cities (P < .0001) (Figure 1B). In contrast, during the baseline period (January 1, 2014 through February 28, 2014), there was no difference between UpToDate MERS searches in Jeddah compared with those in the composite of the control cities (P = .936). Likewise, during the outbreak period in 2014, UpToDate MERS searches in Riyadh showed a correlation to the reported MERS cases; the correlation coefficient was 0.651 (P < .00001) (Figure 2A). UpToDate MERS searches in Riyadh during the outbreak period were significantly higher than those in the composite of the 4 control cities (P < .0001) (Figure 2B). In contrast, during the baseline period (January 1, 2014 through February 28, 2014), there was no difference between UpToDate MERS searches in Riyadh compared with the composite of the 4 control cities (P = .904). During the outbreak in 2015 in Riyadh, UpToDate MERS searches in Riyadh also showed a correlation to the reported MERS cases (Figure 3); the correlation coefficient was 0.860 (P < .0001).

From January 1 to February 28, 2014 (before the first outbreak analyzed), the average daily number of UpToDate searches on any subject in Jeddah was 548. From March 3 to May 16, 2014 (during the first outbreak analyzed), the average daily number of UpToDate searches in Jeddah was 620. From January 1 to February 28, 2014 (before the second outbreak analyzed), the average daily number of UpToDate searches in Riyadh was 5561. From March 29 to May 21, 2014 (during the second outbreak analyzed), the average daily number of UpToDate searches in Riyadh was 5269. From April 11 to June 13, 2015 (before the third outbreak analyzed), the average weekly number of UpToDate searches in Riyadh was 22 526. From June 20 to October 3, 2015 (during the third outbreak analyzed), the average weekly number of UpToDate searches in Riyadh was 15 370.

DISCUSSION

Several studies support the utility of using internet-based searches for detecting infectious disease outbreaks, but most of these studies have used search engines that are used by the general public [1–6]. Digital infectious disease surveillance techniques using large search engines such as Google Flu Trends show promise [2], but, in some cases, they have underestimated (during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic) or overestimated (during the 2012–2013 influenza season) disease prevalence [14–17].

Our findings suggest that analysis of UpToDate search activity could be useful for detecting and monitoring MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia. Although some of the UpToDate MERS searches may have been prompted by media reports, one study suggested that UpToDate searches related to influenza-like illness are less likely to be impacted by public anxiety and media reports and appear to have improved signal-to-noise ratios compared with internet searches by Google Flu Trends [3]. This may be because the majority of UpToDate users are clinicians.

Additional studies are needed to determine whether UpToDate search queries can be used to detect and monitor MERS outbreaks in other regions or to detect and monitor other infectious disease outbreaks around the world. If additional investigation further validates our approach, then UpToDate searches could be used to augment the existing surveillance techniques used by public health authorities. This could be especially valuable in regions of the world that have weak public health infrastructure [5].

Limitations of this study are that we analyzed only a small number of MERS outbreaks in specific cities and that we evaluated these outbreaks retrospectively. However, this approach was required to compare our search query results with cases that have been reported in the literature. In addition, we compared the timing of UpToDate MERS searches with the timing of onset of illness because the majority of cases reported in the literature were classified by date of onset of illness rather than by date of laboratory diagnosis [11, 12]. Using these dates, it was not possible to determine whether UpToDate searches were able to detect a signal before the reporting of cases to public health authorities.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis suggests that UpToDate search activity is useful for detecting and monitoring outbreaks of MERS in Saudi Arabia. This report is consistent with the findings of a previous study that demonstrated the utility of UpToDate searches for tracking influenza-like illnesses in the United States. Further studies are warranted to determine whether UpToDate searches can be used to detect and monitor outbreaks caused by other pathogens and whether it can be used in other geographic regions.

Acknowledgments

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors are employees of UpToDate, Wolters Kluwer Health.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Polgreen PM, Chen Y, Pennock DM, Nelson FD. Using internet searches for influenza surveillance. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:1443–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsberg J, Mohebbi MH, Patel RS et al. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 2009; 457:1012–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santillana M, Nsoesie EO, Mekaru SR et al. Using clinicians' search query data to monitor influenza epidemics. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1446–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahk GJ, Kim YS, Park MS. Use of internet search queries to enhance surveillance of foodborne illness. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1906–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milinovich GJ, Williams GM, Clements AC, Hu W. Internet-based surveillance systems for monitoring emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson SH, Benedum CM, Mekaru SR et al. Drivers of emerging infectious disease events as a framework for digital detection. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odgers DJ, Harpaz R, Callahan A et al. Analyzing search behavior of healthcare professionals for drug safety surveillance. Pac Symp Biocomput 2015; 306–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callahan A, Pernek I, Stiglic G et al. Analyzing information seeking and drug-safety alert response by health care professionals as new methods for surveillance. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17:e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Thailand. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/29-january-2016-mers-thailand/en/ Accessed 3 February 2016.

- 10.Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015; 386:995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oboho IK, Tomczyk SM, Al-Asmari AM et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah--a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagbo SF, Skakni L, Chu DK et al. Molecular epidemiology of hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1981–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean. MERS-CoV situation update - 30 November 2015. Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/csr/documents/MERS-CoV_30_November.pdf Accessed 4 February 2016.

- 14.Butler D. When Google got flu wrong. Nature 2013; 494:155–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazer D, Kennedy R, King G, Vespignani A. Big data. The parable of Google Flu: traps in big data analysis. Science 2014; 343:1203–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin LJ, Xu B, Yasui Y. Improving Google Flu Trends estimates for the United States through transformation. PLoS One 2014; 9:e109209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson DR, Konty KJ, Paladini M et al. Reassessing Google Flu Trends data for detection of seasonal and pandemic influenza: a comparative epidemiological study at three geographic scales. PLoS Comput Biol 2013; 9:e1003256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]