Abstract

The aim of this study was to develop a novel microbially triggered and animal-sparing dissolution method for testing of nanorough polysaccharide-based micron granules for colonic drug delivery. In this method, probiotic cultures of bacteria present in the colonic region were prepared and added to the dissolution media and compared with the performance of conventional dissolution methodologies (such as media with rat cecal and human fecal media). In this study, the predominant species (such as Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus species, Eubacterium and Streptococcus) were cultured in 12% w/v skimmed milk powder and 5% w/v grade “A” honey. Approximately 1010–1011 colony forming units m/L of probiotic culture was added to the dissolution media to test the drug release of polysaccharide-based formulations. A USP dissolution apparatus I/II using a gradient pH dissolution method was used to evaluate drug release from formulations meant for colonic drug delivery. Drug release of guar gum/Eudragit FS30D coated 5-fluorouracil granules was assessed under gastric and small intestine conditions within a simulated colonic environment involving fermentation testing with the probiotic culture. The results with the probiotic system were comparable to those obtained from the rat cecal and human fecal-based fermentation model, thereby suggesting that a probiotic dissolution method can be successfully applied for drug release testing of any polysaccharide-based oral formulation meant for colonic delivery. As such, this study significantly adds to the nanostructured biomaterials’ community by elucidating an easier assay for colonic drug delivery.

Keywords: probiotic media, colon specific drug delivery, dissolution methodologies, simulated colonic media, microbially triggered drug delivery

Introduction

Colon specific drug delivery systems (CDDS) afford the most advantages for many local treatments of colonic disorders/diseases such as colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease (which is of two types, ie, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), and other local bacterial infections.1,2 The approaches which are commonly used for a drug to reach the colon include a prodrug design approach, a time-dependent system, a pH sensitive polymeric approach, and microflora-activated delivery systems.3,4 Among the aforementioned systems, the microflora-triggered delivery systems have been found to be the most promising because specific colonic enzymes degrade the polysaccharide coating for drug release.5–7 The main principle of action of microflora-activated systems is enzymatic degradation of polysaccharides (such as chitosan, inulin, guar gum, cellulose, xanthan gum, amylose, alginates, dextran, pectin, khaya, and albizia gum) present in the system by colonic bacteria.8,9

In vitro evaluation of these systems remains a challenge in dissolution studies inhibiting the further discovery of treatment regimes. Moreover, the anaerobic microflora that are highly specific to the colonic region are challenging to assimilate into USP dissolution methods. As a consequence, alternative dissolution approaches have been designed to better represent colonic conditions in vitro. A rationally developed dissolution method with a proper justification can be used to estimate drug release kinetics as well as the pH effect and hydrodynamic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract on drug release characteristics.

In order to fulfill these aforementioned requirements, it is essential that the dissolution method be discriminative, reproducible, biorelevant, and more importantly, scientifically justifiable. When a drug product application is sent to the regulatory agencies, the dissolution methodology and its use as a quality control tool are the essential parts of that application.10

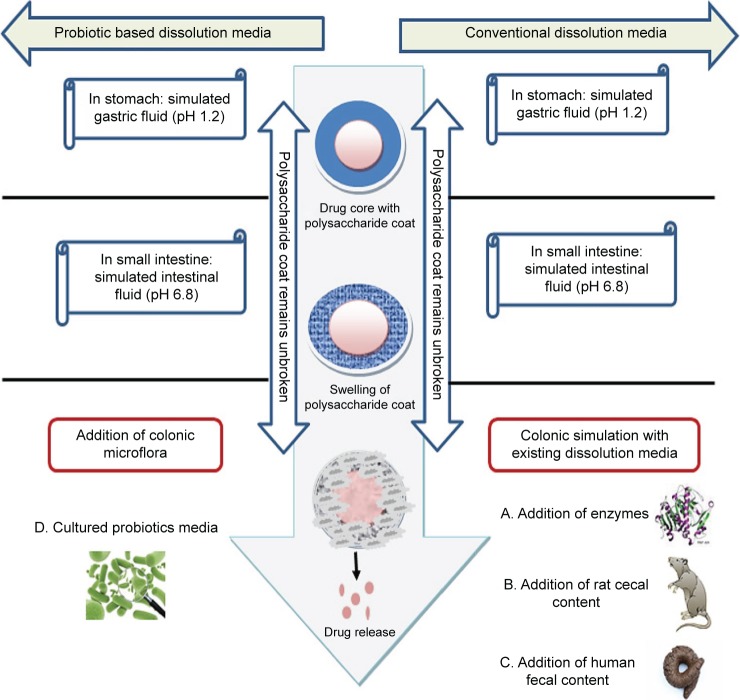

In the last decade, a number of biorelevant media have been developed to simulate conditions encountered by formulations designed for colon targeting (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Current dissolution methods to test the drug release of polysaccharide-based CDDS.

Abbreviation: CDDS, colon-based drug delivery system.

The most commonly used dissolution testing methods for these delivery systems (which have few limitations11) involve the addition of enzymes,11–17 rat cecal contents,18–21 and human fecal slurries.22–31

Under colonic conditions, enzymes are continuously replenished by the microbiota that secretes these enzymes. However, for the in vitro methods used, the concentration of the enzymes used in the media decreases. The second method using rat cecal content requires the sacrifice of a large number of animals and human fecal content usage is not pragmatic because it would not be practical to obtain fecal samples every time without significant batch-to-batch variations.10

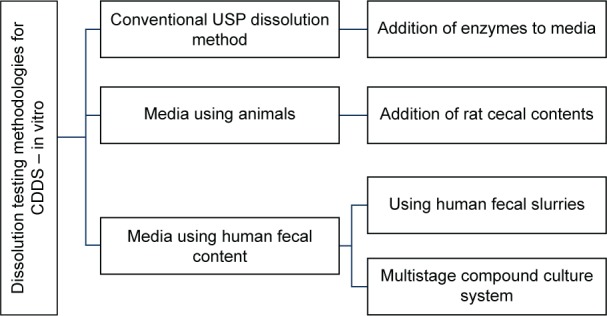

In this paper, therefore, an approach was made to develop an animal-sparing dissolution media using probiotics to test the drug release of guar gum/Eudragit FS30D coated 5-fluorouracil granules (5-FU) (Figure 2). Dissolution media with probiotics were compared with existing rat cecal and human fecal media. Moreover, an important part of this work was to create micron granules with nanostructured roughness, since numerous studies have demonstrated that nanoroughness can decrease inflammation and immune system recognition.32,33 This is because nanoroughness can alter the surface energy of granules and control initial protein adsorption (such as decreased IgG adsorption) to inhibit inflammatory cell responses. Such events would allow the drug capsule to be more effective at delivering drugs to targeted sites.

Figure 2.

Outline of drug release during in vitro dissolution testing of polysaccharide-based colon-targeted drug delivery system using (A) enzymes, (B) rat cecal contents, (C) human fecal contents, and (D) cultured probiotics media.

Materials and methods

Materials

5-FU was procured from Jackson Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Punjab, India. Guar gum and Xanthan gum were obtained from Molychem Manufacturers Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Eudragit FS30D was acquired from Evonik Industries, Essen, Germany. Probiotics were purchased from Eris Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd., Gujarat, India. Grade “A” honey was obtained from Dabur India Ltd., New Delhi, India. Dry milk powder was purchased from Everyday Milk Products, New Delhi, India.

Preparation of 5-FU drug-loaded granule core

The granules were prepared by mixing 5-FU, guar gum, and xanthan gum at a ratio of 1:1:1 (15 g each), (Table 1), in a V-cone blender. Wet granulation of the prepared mass was carried out using purified water. The damp mass was passed through sieve number 10 initially; a larger size fraction was obtained by using sieve number 30 with a mesh size of 0.59 mm. The prepared granules were dried for 30 minutes in a hot air oven at 40°C–50°C.

Table 1.

Composition of guar gum and Eudragit FS30D coated 5-fluorouracil granules

| Serial number | Composition | Quantity (g) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5-fluorouracil | 15 |

| 2 | Guar gum | 15 |

| 3 | Xanthan gum | 15 |

| 4 | Guar gum 20% dispersion | 9 |

| 5 | Eudragit FS30D 40% | 18 (ie, 60 mL) |

Coating of the prepared granules

The prepared granules were coated up to 20% (9 g guar gum in 900 mL water for 45 g granules bed) with guar gum in an accela cota coating pan (Thomas Engineering, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA). The process parameters were as follows: an inlet temperature of 40°C±2°C, product temperature of 37°C±2°C, and spray rate of 0.2 g/min. This gum layer acts as a triggering mechanism for the drug release in the colon by colonic microflora. Further, the granules were coated with 40% (ie, 18 g in 60 mL of Eudragit FS30D) Eudragit FS30D to retard the drug release in the stomach and small intestine.

Filling of coated granules in hard gelatin transparent capsules

The weight equivalent to 50 mg of coated granules of 5-FU were filled in hard gelatin capsules manually.

Determination of drug content

The weight equivalent to 50 mg of 5-FU was transferred to a volumetric flask containing about 50 mL of pH 6.8 phosphate buffer and mixed thoroughly. The remainder of the volume to 100 mL was made up with a pH 6.8 buffer. The solutions were filtered through 0.22 μm membrane filters. The drug content was measured using reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC; LC-20AD; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 265 nm.

Preparation of dissolution media

Preparation of fresh human fecal content media

Fresh human fecal slurries were generally used to study the fermentation of nonstarch polysaccharides.24 The solution was prepared by homogenizing fresh feces (5% w/v) obtained from healthy humans. Content was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) under anaerobic conditions with carbon dioxide purging. These solutions were finally added to the dissolution vessel to mimic the colonic environment for drug release.

Preparation of rat cecal media

Thirty minutes prior to the fifth hour of the dissolution study, rats were anesthetized and killed. The abdomens were opened, ceca were traced, ligated at both the ends, dissected, and contents were pooled and added to the pH 6.8 phosphate buffer continuously bubbled with carbon dioxide. These solutions were finally added to the dissolution media to give a final cecal dilution of 4% w/v.31

Preparation of probiotic culture media

In order to conduct dissolution testing in the probiotic culture media, the probiotic culture needs to be activated and cultured in a suitable media. A composition of probiotics (total 5 billion; Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Saccharomyces boulardi) and prebiotics (Fructooligosaccharide-100 mg) were used for developing the probiotic dissolution media.

A 5% w/v solution of tempered Grade “A” honey was added to 12% w/v reconstituted nonfat dry milk (NDM) in a 100 mL volumetric flask, and the remaining volume to 100 mL was made up with sterile water. The sample was pasteurized at 70°C for 30 minutes and cooled to 37°C. A single capsule of probiotic powder was slurried in sterile water and was inoculated into the pasteurized milk media and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours under anaerobic conditions.34 The cultured media was counted for total bacteria, which was found to be 9.8×1010 colony forming units (CFU)/mL (1011–1012 CFU/mL normal microbiota count in colon). The prepared probiotic media was added to the dissolution chamber.

Dissolution studies

In vitro drug release of 5-FU granules using human fecal slurries

The drug release experiments were carried out in six 250 mL beakers which were immersed into the dissolution vessels (DS 8000; LAB INDIA, Mumbai, India).27 Six 5-FU capsules were placed in a solution containing 150 mL of pH 1.2 HCl buffer at 37°C±0.5°C for 2 hours at 100 rpm. After 4 hours, the pH was adjusted to 6.8–7.5 using 50 mL of phosphate buffer and sodium hydroxide.

At the end of the fourth hour, the media was degassed using CO2 to remove undissolved oxygen and anaerobic conditions were maintained in the media for 15 minutes. A 5% w/v solution of freshly prepared fecal content was added to the dissolution media, and the study was continued for up to 24 hours with continuous purging of CO2 throughout the study.

About 1.0 mL of each sample was withdrawn at regular time intervals and was replaced by the fresh media which was maintained under anaerobic conditions. The volume of the sample was adjusted to 10 mL and solutions were filtered by using 0.22 μm membrane filters. Twenty μL of this solution was injected into an HPLC (LC-20AD; Shimadzu). All the studies were repeated six times and the mean data were recorded. The stationary phase used was a Kinetex 5U C-18 Column (250×4.6 mm2 ID: particle size 5 μm), with a mobile phase [Isocratic mode] of 40 mM monobasic potassium phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 7.0. The flow rate was kept at 0.5 mL/min and the retention time was found to be 5.5 minutes at 265 nm. The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional animal ethical committee of Lovely Professional University, Punjab (letter number- 954/ac/06/CPCSEA/12/8).

In vitro drug release of 5-FU granules using rat cecal media

The drug release experiments were carried out in six 250 mL beakers which were immersed into the dissolution vessels (DS 8000; LAB INDIA). Six 5-FU capsules were placed in a solution containing 150 mL of pH 1.2 HCl buffer at 37°C±0.5°C for 2 hours at 100 rpm. After 4 hours, the pH was adjusted to 6.8 using 50 mL of phosphate buffer and sodium hydroxide. A 4% w/v solution of rat cecal content was added to the dissolution media and the study was continued for up to 24 hours with continuous purging of CO2. About 1.0 mL of each sample was withdrawn at regular time intervals and replaced by fresh media which was maintained under anaerobic conditions. The volume of the sample was adjusted to 10 mL and solutions were filtered using 0.22 μm membrane filters and analyzed using RP-HPLC.

In vitro drug release of 5-FU granules using probiotic culture

The drug release experiments were carried out in six 250 mL beakers which were immersed into the dissolution vessels (DS 8000; LAB INDIA). Six 5-FU capsules were placed in a solution containing 150 mL of pH 1.2 HCl buffer at 37°C±0.5°C for 2 hours at 100 rpm. Afterwards, the pH of the dissolution media was adjusted to 6.8–7.5 with 50 mL of pH 6.8 buffer and sodium hydroxide, and the study continued for another 1 hour. At the end of the third hour, the media was degassed using carbon dioxide gas to remove the undissolved oxygen and to maintain anaerobic conditions inside the media for 10 minutes. Then, the entire volume of the prepared probiotic culture (9.8×1010 CFU/mL) was added to the dissolution media and the study was continued up to 24 hours with continuous purging of CO2 throughout the study. About 1.0 mL of each sample was withdrawn at regular time intervals and replaced by the fresh media. The volume of the sample was adjusted to 10 mL and solutions were filtered by using 0.22 μm membrane filters and analyzed using RP-HPLC. The studies on the aforementioned 5-FU multiparticulate granules were also carried out in the same manner but without adding the probiotic culture, rat cecal content, and/or human fecal contents (ie, pH buffer media).

Results and discussion

Drug content in 5-FU granules and characterization

Results showed that the present granules were approximately 500–600 μm in diameter and showed nanoscale roughness (Figure 3). Again, implementing nanoscale roughness on the granules was important because numerous studies have indicated that nanoscale roughness can decrease inflammation and immune system recognition allowing the granules to reach their destination and release drugs.32,33 Of course, more testing is necessary to confirm this. Moreover, the drug content of the guar gum and Eudragit FS30D coated granules for 5-FU was found to be 96.5%.

Figure 3.

SEM image of the granules of interest to the present study.

Note: Magnification, 100 microns.

Abbreviation: SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

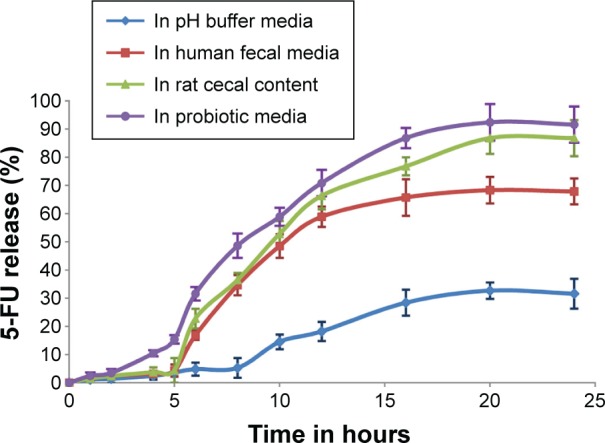

Drug release comparison in different media

The in vitro release profile of guar gum and Eudragit FS30D coated 5-FU granules containing capsules in different dissolution media is shown in Figure 4. The study revealed that in all cases, the 5-FU release was less than 10% in upper gastric tract and had a tendency to accelerate in the presence of the probiotic media when compared to human fecal media as well as rat cecal media.

Figure 4.

Dissolution profile of 5-FU granules in buffer, fecal, rat cecal, and probiotic media.

Note: Values represents mean of three determinations and bars represent ± SEM.

Abbreviations: SEM, standard error of the mean; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

After 24 hours, the capsules subjected to media containing probiotic cultures showed a release rate of 91.61% as compared to media containing fecal slurries (67.88%) and rat cecal content (86.81%). The obtained results showed superior dissolution potential of the developed probiotic media over human fecal slurries and rat cecal content. Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus species and Bacteroids were the most predominant bacteria in the media which degraded the guar gum and xanthan gum coating, triggering effective drug release in both the probiotic and rat cecal media compared to human fecal media. The results with the probiotic system were comparable to those obtained from rat cecal- and human fecal-based fermentation model, thereby suggesting that the probiotic dissolution method can be successfully applied.

Microbially triggering CDDS are based on the manipulation of the specific enzymatic degradation of the colon microflora (Bifidobacterium, Bacteroids, Lactobacillus, and enterobacteria). These colonic bacterial milieu are predominately anaerobic in nature and secrete enzymes that are capable of metabolizing various polysaccharides that escape digestion in the upper gastric tract. Colon microflora have the capability of fermenting innumerable types of substrates that have been left undigested in the small intestine, eg, di- and trisaccharides, polysaccharides, etc. For this fermentation, the microflora produce various enzymes like glucoronidase, xylosidase, arabinosidase, galactosidase, and azo reductazes. Because of the presence of the biodegradable enzymes only in the colon, the use of biodegradable polymers for colon-specific drug delivery seems to be more site-specific compared to pH- and time-dependent approaches.

Conclusion

Pharmaceutical approaches commonly used in CDDS include triggering by changes in pH or enzymatic conditions or activation by microbial flora of the gastrointestinal tract. An efficacious colon drug-delivery system needs an in-built mechanism in the delivery system to only respond to the physiological surroundings specific to the colon. Due to the lack of similarities in the upper and lower gastrointestinal physiological conditions, strategies which are generally used to achieve colonic drug delivery, comprise a timed releasing system, coating with pH sensitive polymer layers, prodrug methodology, and colonic microflora-activated delivery systems. Among all the systems, the microflora activated delivery systems have been found to be the most effective scaffold systems since the abrupt escalation of the bacteria population and associated enzymatic activities in the ascending colon signifies a noncontinuous event independent of gastrointestinal transit time and pH conditions. The foremost principle in microflora-activated systems is a series of polysaccharides which evade enzymatic degradation in the small intestine and that are predominantly metabolized by colon bacteria to release the therapeutic agents.

To date, in vitro characterization specific to in vitro dissolution of these systems remains a challenge in drug release studies. Moreover, the resident microbiota that are highly specific to the colon are difficult to incorporate into the USP dissolution methodologies. As a consequence, alternative dissolution approaches have been designed to better represent the colonic conditions. A rationally developed dissolution method with a proper justification can be used to estimate drug release kinetics as well as the impact of pH and hydrodynamic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract on drug release characteristics.

This study was aimed at developing an animal-sparing, cost-effective dissolution media to test the drug release of polysaccharide-based formulations meant for the colon, by using probiotics. Probiotic culture was used in dissolution media to mimic the colonic microflora conditions. This approach shows that the dissolution media used for evaluating the drug release of pharmaceuticals meant for colon-specific drug delivery is possible. The dissolution profiles in the current test media (probiotic media) were found to be very similar to those acquired with the rat cecal content and fecal slurries media. More specifically, the current technique shows the development of animal sparing dissolution media for testing the drug release of microgranules of nanorough polysaccharide-based formulations used for colon-specific drug delivery. Of course, the current system needs to be validated and tested with various other drug-polysaccharide-based delivery systems before widespread implementation should occur.

Acknowledgments

The financial assistance and facilities provided by the Dean and Chancellor of Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India, are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure

NGK declares that this work was from his MS dissertation work, supported by the Lovely Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Watts P, Illum L. Colonic drug delivery. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1997;23:893–913. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinget R, Kalala W, Vervoort L, Mooter GU. Colonic drug targeting. J Drug Target. 1998;6:129–149. doi: 10.3109/10611869808997888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubinstein A. Approaches and opportunities in colon-specific drug delivery. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1995;12:101–149. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v12.i2-3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang LB, Chu JS, Fix JA. Colon – specific drug delivery: new approaches and in vitro/in vivo evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2002;235:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saffran M, Kumar GS, Savariar C, Burnham JC, Williams F, Neckers DC. A new approach to the oral administration of insulin and other peptide drugs. Science. 1986;233:1081–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.3526553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonin KH, Saano V, Bieck P, et al. Colonic absorption of human calcitonin in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;83:627–631. doi: 10.1042/cs0830627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotz U, Schwab M. Topical delivery of therapeutic agents in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basit AW. Advances in colonic drug delivery. Drugs. 2005;65:1991–2007. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565140-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hovgaard L, Brøndsted H. Current applications of polysaccharides in colon targeting. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1996;13:185–223. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v13.i3-4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotla NG, Gulati M, Singh SK, Shivapooja A. Facts, fallacies and future of dissolution testing of polysaccharide based colon specific drug delivery. J Control Release. 2014;178:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siewert M, Dressman J, Brown CK, Shah VP, FIP. AAPS FIP/AAPS guidelines to dissolution/in vitro release testing of novel/special dosage forms. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2003;4:E7. doi: 10.1208/pt040107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong D, Larrabee S, Clifford K, Tremblay J, Friend DR. USP dissolution apparatus III (reciprocating cylinder) for screening of guarbased colonic delivery formulations. J Control Release. 1997;47:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang LB, Watanabe S, Li J, et al. Effect of colonic lactulose availability on the timing of drug release onset in vivo from a unique colon-specific drug delivery system (CODES™) Pharm Res. 2003;20:429–434. doi: 10.1023/a:1022660305931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takemura S, Watanabe S, Katsuma M, Fukui M. Human gastrointestinal transit study of a novel colon delivery system (CODES™) using γ-scintigraphy. Paper presented at: 27th International Symposium on Controlled Release of Bioactive Material; 2000; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji C, Xu H, Wu W. In vitro evaluation and pharmacokinetics in dogs of guar gum and Eudragit FS30D-coated colon-targeted pellets of indomethacin. J Drug Target. 2007;15(2):123–131. doi: 10.1080/10611860601143727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fetzner A, Böhm S, Schreder S, Schubert R. Degradation of raw or film incorporated β-cyclodextrin by enzymes and colonic bacteria. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;58(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karrout Y, Neut C, Wils D, et al. Enzymatically activated coated multiparticulates containing theophylline for colon targeting. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2010;20:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karrout Y, Neut C, Wils D, et al. Novel polymeric film coatings for colon targeting: drug release from coated pellets. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;37:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinstein A, Radai R, Ezra M, Pathak S, Rokem JS. In vitro evaluation of calcium pectinate: a potential colon-specific drug delivery carrier. Pharm Res. 1993;10:258–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1018995029167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain A, Gupta Y, Jain SK. Potential of calcium pectinate beads for target specific drug release to colon. J Drug Target. 2007;15:285–294. doi: 10.1080/10611860601146134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha VR, Mittal BR, Bhutani KK, Kumria R. Colonic drug delivery of 5-fluorouracil: an in vitro evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2004;269:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore WE, Cato EP, Holdeman LV. Some current concepts in intestinal bacteriology. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:S33–S42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.10.S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephen AM, Cummings HJ. The microbial contribution to human faecal mass. J Med Microbiol. 1980;13:45–56. doi: 10.1099/00222615-13-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milojevic S, Newton JM, Cummings JH, et al. Amylose as a coating for drug delivery to the colon: preparation and in vitro evaluation using 5-aminosalicylic acid pellets. J Control Release. 1996;38:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molly K, Vande Woestyne M, Verstraete W. Development of a 5-step multi-chamber reactor as a simulation of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;39:254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00228615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schacht E, Gevaert A, Kenawy ER, et al. Polymers for colon specific drug deliver. J Control Release. 1996;39:327–338. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niranjan K, Ashwini S, Jagadish M, Pinakin P. Effect of guar gum and xanthan gum coating on release studies of metronidazole in human fecal media for colon targeted drug delivery systems. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6(2):315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH, Macfarlane S, Gibson GR. Influence of retention time on degradation of pancreatic enzymes by human colonic bacteria grown in a 3-stage continuous culture system. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;67(5):520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitarresi G, Casadei MA, Mandracchia D, Paolicelli P, Palumbo FS, Giammoxna G. Photo crosslinking of dextran and polyaspartamide derivatives: a combination suitable for colon-specific drug delivery. J Control Release. 2007;119(3):328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugurlu T, Turkoglu M, Gurer US, Akarsu BG. Colonic delivery of compression coated nisin tablets using pectin/HPMC polymer mixture. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67(1):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnaiah YS, Bhaskar Rheddy PR, Satyanarayana V, Karthikeyan RS. Studies on the development of oral colon targeted drug delivery systems for metronidazole in the treatment of amoebiasis. Int J Pharm. 2002;236:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S, Chio J, Shin S, et al. Analysis on migration and activation of live macrophages on transparent flat and nanostructured titanium. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(5):2337–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amancherla R, Ercan B, Balasubramanian K, Webster TJ. Reduced adhesion of macrophages on anodized titanium with select nanotube surface features. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1765–1771. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S22763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ustunol Z. The effect of honey on the growth of Bifidobacteria. National Honey Board. [Accessed September 25, 2012]. Available from: http://www.honey.com/images/uploads/general/bifidobacteria.pdf.