Abstract

Summary: Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) lack tertiary structure and thus differ from globular proteins in terms of their sequence–structure–function relations. IDPs have lower sequence conservation, different types of active sites and a different distribution of functionally important regions, which altogether make their multiple sequence alignment (MSA) difficult. The KMAD MSA software has been written specifically for the alignment and annotation of IDPs. It augments the substitution matrix with knowledge about post-translational modifications, functional domains and short linear motifs.

Results: MSAs produced with KMAD describe well-conserved features among IDPs, tend to agree well with biological intuition, and are a good basis for designing new experiments to shed light on this large, understudied class of proteins.

Availability and implementation: KMAD web server is accessible at http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/kmad/. A standalone version is freely available.

Contact: vriend@cmbi.ru.nl

1 Introduction

More than 30% of all human proteins contain unfolded regions (Pentony and Jones, 2010). This stands in marked contrast to how little we know about them (Van der Lee et al., 2014). Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) lack a stable tertiary structure, and thus lack a hydrophobic core. They thus also lack an active site. IDPs often interact with other proteins by means of short linear motifs (SLiMs), which are very abundant in disordered regions. This is a fundamental component of cell signalling (Gibson, 2009). These IDP characteristics have many consequences for aligning their sequences and thus for their study in general. Algorithms underlying existing MSA software are directly or indirectly based on knowledge obtained from studying 3D protein structures. Aligning a hydrophobic residue in the protein core with a hydrophilic one is penalized heavily when aligning ordered proteins, but this is much less the case when aligning IDPs simply because IDPs do not have a hydrophobic core. In addition, folded proteins contain large protein–protein interaction surfaces, ion binding sites, active sites or other 3D motifs that MSA software capitalizes on, while IDPs generally consist of short motifs surrounded by stretches of highly variable length and composition. The main function determinants of IDPs are SLiMs, and posttranslational modifications (PTMs).

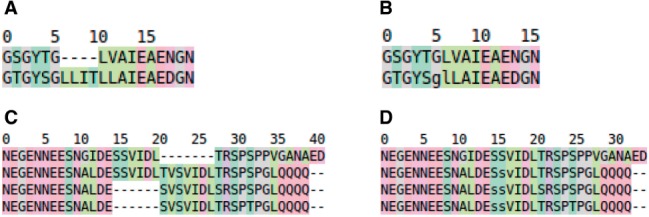

For the specific purpose of aligning IDPs, we introduce Knowledge-based multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for IDPs, or KMAD, that incorporates SLiM, domain and PTM annotations in the alignment procedure. Obviously, the inclusion of this knowledge will cause these motifs to line up in the final MSA without certainty that this reflects biological reality. This way, however, KMAD generates hypotheses that can be validated experimentally to progress, for example, protein engineering, drug design or the analysis of genetic disorders. In these research fields, scientists most often are interested in one single protein and want to gather information for this one protein. In the particular case of IDPs such information normally relates to SLiMS and PTMs and how conserved these are in an MSA. In the HSSP project (Sander and Schneider, 1991), the concept of the insertion-free MSA was introduced specifically for this purpose (see Fig. 1). Although KMAD can produce ‘normal’ MSAs (i.e. with insertions and deletions possible in all sequences), we tend to use it insertion-free when studying IDP MSAs.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical example of an insertion free alignment. (A) ‘normal’ MSA. (B) The same alignment, but with the insertions removed from the first sequence. Obviously the residues in the other sequence that aligned with the removed insertions were removed too. The residues g and l are in lower case characters to indicate that an insertion was removed between them. (C, D) Illustrating how the removal of insertions from the sequence of interest can increase the amount of information that can be extracted from the MSA. In (C), the SVIDL motif is duplicated in the second sequence. In the third and fourth sequences these motifs are more similar to the second instance of the motif in sequence two than to the first instance. By removing the insertion we learn that the SVIDL motif in the first sequence indeed is conserved, and any knowledge available for these residues in the bottom two sequences can be transferred to the first sequence

MSA validation is a hotly debated issue that seems mostly unsolved (Iantorno et al., 2014). Even worse, for the same set of sequences different MSAs can be produced that all seem correct (Iantorno et al., 2014). Alignments extracted from structure superpositions are generally considered the gold standard, but many examples exist in which a structure superposition-derived MSA does not reflect well the sequence family’s phylogeny (Iantorno et al., 2014). The MSA benchmark suites BAliBASE (Thompson et al., 2005; Perrodou et al., 2008) and PREFAB (Edgar, 2004) are mostly structure superposition based, albeit that superpositions used in these suites do not always agree (Edgar, 2010) with external sources such as CATH (Sillitoe et al., 2015) or SCOP (Andreeva et al., 2008). It is not clear how these discrepancies arose but it is known that the same structures sometimes can be superposed differently depending on the algorithm used and the parameter choices (Irving et al., 2001; Konagurthu et al., 2006). Edgar (2010) recently studied quality measures for protein alignment benchmarks and concluded that ‘protein alignment assessment is more challenging than generally realized’; he also concluded that BAliBASE block identifications do not correlate well with conserved protein secondary structures. We used BAliBASE and PREFAB to validate KMAD’s MSAs and the MSAs produced by a series of well-known alignment programs, and conclude that the differences in alignment validation score between the six methods are smaller than the ‘noise’ in BAliBASE (www.cmbi.ru.nl/kmad/balibase/). It should be noted that KMAD was designed to produce insertion-free alignments (see Fig. 1) that best allow for transfer of information from the whole alignment to the one sequence of interest while BAliBASE and PREFAB contain ‘complete’ alignments that better reflect the underlying phylogeny.

2 Methods

The DisProt database (Sickmeier et al., 2007) of experimentally validated IDPs holds a few hundred IDPs that are useful when designing or validating IDP-specific MSA software. We produced MSAs for DisProt families with ClustalW (Larkin et al., 2007), Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011), MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002), T-Coffee (Notredame et al., 2000) and MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). For each IDP a set of maximally 30 homologous sequences was extracted randomly from SwissProt (The Uniprot Consortium, 2014) using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) (cut-off E-value: ). The sequence sets were aligned with all aforementioned methods and with KMAD. Pfam (Bateman et al., 2004) domains, phosphorylations predicted by NetPhos (Blom et al., 1999) and SLiM and PTM data extracted from both ELM (Dinkel et al., 2013) and SwissProt were mapped onto the alignments. SLiMs were filtered using GO terms (Ashburner et al., 2000) whereby a SLiM was rejected if its set of GO terms and the set of GO terms for all sequences in the MSA were disjoint. The set of GO terms for the SLiM included the parents and all descendants in the GO term hierarchy. For the sequence set, the GO terms of all sequences in the alignment were combined.

The KMAD server can annotate IDPs in the MSA. IDPs are either obtained from the D2P2 database of disorder predictions (Oates et al., 2013), or by running the freely available disorder predictors: GlobPlot (Linding et al., 2003), DISOPRED (Ward et al., 2004), SPINE-D (Zhang et al., 2012), PSIPRED (Jones, 1999), PreDisorder (Cheng et al., 2005) and IUPred (Dosztányi et al., 2005).

KMAD was designed for the optimal alignment of IDPs. Proteins with a stable tertiary structure (non-IDPs) often also contain PTMs, SLiMs and domains. KMAD can be used for the alignment of non-IDPs too, but better results will be obtained if non-IDPs are first aligned with software optimized for that task (i.e. any software other than KMAD) followed by fine-tuning the resulting alignment with KMAD. We call this the refinement option of KMAD.

MSA quality was evaluated in two ways. First, MSAs made with Clustal Omega and KMAD were visually inspected in light of the known biology. Second, a quantitative analysis was performed with the protein linear motif benchmark for MSA tools from the BAliBASE suite, and with the PREFAB suite.

3 Implementation

KMAD uses a progressive iterative alignment method similar to the MaxHom algorithm (Sander and Schneider, 1991) that is also used in WHAT IF (Vriend, 1990) and the 3DM suite (Joosten, 2007). In this protocol, the starting sequence remains the first sequence in the alignment, and insertions and deletions only occur relative to this first sequence (see Fig. 1). This protocol is particularly useful when studying just one protein as is often done in, for example, DNA diagnostics (Venselaar et al., 2010) or protein engineering. Pairwise alignments are performed using the Gotoh (1982) modification of the Needleman–Wunsch algorithm (Needleman and Wunsch, 1970) that allows for affine gap penalties. KMAD uses an IDP-specific substitution matrix (Midic et al., 2009) and augments the substitution matrix scores with metadata as shown in Figure 2. These metadata include SLiMs, domains and PTMs as listed in the ‘Method’ section. Elements in KMAD’s alignment matrix thus get a similarity score augmented with feature scores. When aligning a sequence to the profile, a serine, for example, gets a score based on the profile, augmented with scores for observed or predicted phosphorylations, for being part of a SLiM, or for being located in a PFAM domain.

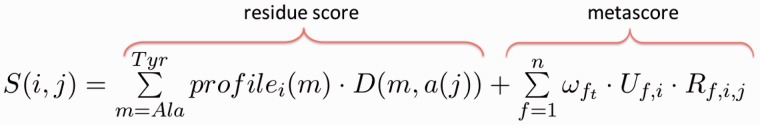

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of KMAD’s scoring function; i and j are positions in the profile and in the sequence, respectively; profilei is a vector of length 20 that contains the frequencies of the 20 amino acid types m at position i in the alignment that resulted from the previous iteration (in the first iteration all profile values are 0 or 1, according to the first sequence). D is an IDP-specific 20 × 20 substitution matrix (Midic et al., 2009). The residue score is the convolution of the profile vector for i and the D column for j. are weights for the three feature types ft ( weights optionally can be set by the user). values for PTMs and SLiMs are determined from the conservation of that feature at i. values for domains are the conservation of the domain at position i minus the conservation of all other domains at that position. The terms R relate to the perceived reliability (PR) of the feature; experimentally determined PTMs, for example, weigh three times higher than predicted ones. is the product of the average PR of the feature f at position i in the profile and the PR of this feature at position j in the sequence. The metascore for j is the weighted sum of scores for all observed features

KMAD uses higher Rf for observed features than for predicted ones. For example, features that SwissProt annotates with an experimental evidence code get , while SwissProt’s automatically assigned evidence code results in , and NetPhos predictions get . The Rf for ELMs SLiMs are derived from ELMs probability values, and range from 0 to 1. Default values were determined from manual inspection of a large number of KMAD MSAs produced with a wide variety of parameter combinations. These weights presently are 10.0, 4.0 and 4.0 for PTMs, SLiMs and domains, respectively, and small modifications of these weights seem to not influence the final results very much. All scores, weights and factors are explained in detail at the KMAD website.

4 Results

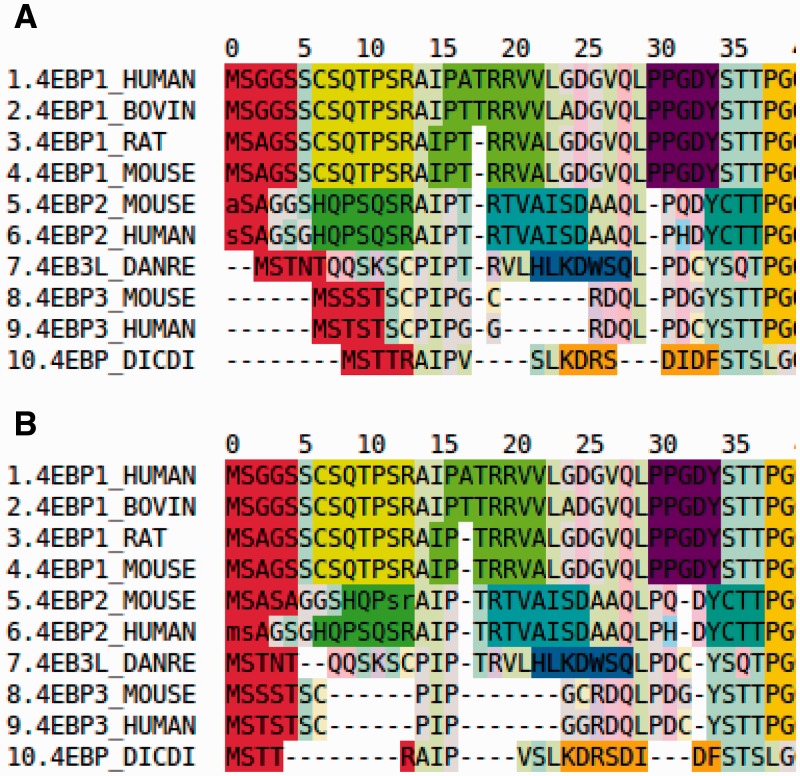

KMAD overcomes several problems encountered with other methods when aligning IDPs. Two examples are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The first example (Fig. 3) illustrates the advantage of KMAD’s use of SLiMs. Clustal Omega spreads out the LIG_BIR_II_1 motif. In the KMAD alignment, the motif is lined up nicely in all sequences but 2. Even if this predicted SLiM should not be aligned as in the B panel of Figure 3, the bioscientist will still benefit from awareness of the presence of this conserved motif in the N-terminal segment.

Fig. 3.

Excerpts from Clustal Omega and KMAD alignments of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1. (A) Clustal Omega alignment annotated with motifs; (B) KMAD alignment annotated with motifs. Each of the bright colours represents a different motif (a bright red background indicates the LIG_BIR_II_1 motif; further colour details are given at the project website)

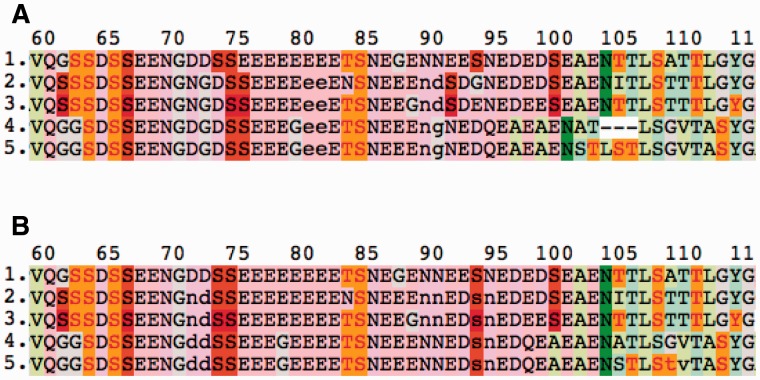

Fig. 4.

Excerpts from Clustal Omega and KMAD alignments of human sialoprotein (SIAL_HUMAN) with four homologues. (A) Clustal Omega alignment annotated with PTMs; (B) KMAD alignment annotated with PTMs. PTM sites are highlighted with bright colours (red is annotated phosphorylation, orange is predicted phosphorylation, green is N-linked glycosylation; further colour details are given on the project website). The two serines that seem to appear in the sequences 4 and 5 around position 93 in the KMAD alignment are located in the gap (indicated with lowercase characters) around position 90 in the Clustal Omega alignment. In DNA analysis, protein engineering, etc, this software feature is used frequently. The gapped alignment that provides a more phylogeny-oriented view on this sequence family is available at the KMAD website

The second example (Fig. 4) illustrates the use of PTMs. The phosphorylated serines at positions 74 and 75 in the first sequence are shifted to the left relative to the columns of phosphorylated serines at positions 75 and 76 in the other four sequences. A gap at position 73 in the query sequence would be a better solution in this case, but because we want to keep the first sequence indel-free, an insertion is introduced in all other sequences. The phosphorylated serine at position 94 in the first sequence seems better aligned with the serines at position 92 in sequences 2 and 3, and indeed, KMAD finds this solution.

Eventually, glycosylated asparagines at position 102 in sequences 4 and 5 should most probably be aligned to asparagines at position 105 from sequences 1–3. All problems mentioned above are solved by KMAD with no harm to the rest of the alignment. The problem that the predicted threonine phosphorylation sites around position 106 cannot be lined up is beyond KMAD’s reach.

Figures 3 and 4 provide two examples in which knowledge of the presence of sequence motifs is used to better align those motifs. This method is of course highly cyclic and we therefore compared the performance of KMAD with five other MSA methods using the BAliBASE and PREFAB suites. Most proteins in these benchmarks have a stable 3D structure, while KMAD was designed for the alignment of IDPs. We therefore used KMAD in refinement mode starting with Clustal Omega alignments. To avoid circularity when testing KMAD on the BAliBASE motif reference set we performed a leave-one-out validation, i.e. in each alignment the motif annotated by BAliBASE was excluded from the KMAD annotations.

The score differences in Table 1 are all within the margin of error, given that noise in the benchmarks (www.cmbi.ru.nl/kmad/balibase/) contributes a few percent to the scores.

Table 1.

Results from the BAliBASE motif reference set, subset RV913 containing sequences with 40–80% sequence identity

| Method | Mean general alignment score | Mean motif score |

|---|---|---|

| T-Coffee | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| Clustal Omega | 0.93 | 0.86 |

| Clustal Omega refined with KMAD | 0.93 | 0.90 |

| KMAD | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| MAFFT | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| MUSCLE | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| ClustalW2 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

More BAliBASE results and also PREFAB benchmarking results are available at the KMAD website.

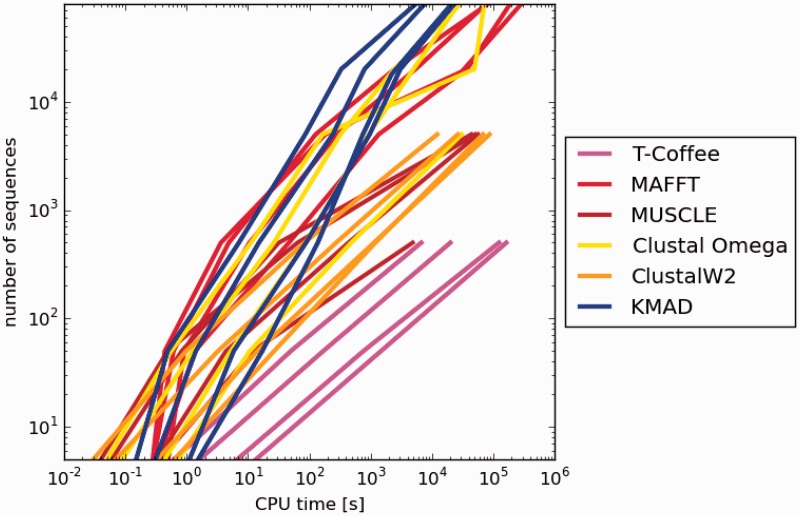

We chose four sequence families for testing the CPU performance of the six methods. The sequences in these families on average are about 150, 250, 550 and 750 amino acids long, respectively. From each family subsets of 5, 50, 500, 5 K, 20 K and 80 K were selected and these 24 groups of sequences were aligned with each of the six methods using each time one core on the same computer that had more than adequate RAM, so that the wall-time of each calculation provided a good measure for the CPU performance of the method. The results are visualized in Figure 5. In this plot, some points are missing because we stopped each alignment when after 1 week no result had been returned yet. Clearly, KMAD outperforms the other methods for large alignments.

Fig. 5.

Log–log plot of CPU performance. The abscissa and ordinate are logarithmic scales for the CPU time and the number of sequences, respectively. For every method there are four curves each representing a different protein family

5 Discussion

In the field of sequence alignment research it is common practice to compare the sequence alignments obtained with MSA software with those that are obtained from structure superpositions (Nguyen and Pan, 2013). IDPs do not possess a static 3D structure so that this method is not applicable here. We have discussed several examples in which KMAD produces IDP alignments that intuitively feel correct, and several more examples are worked out in detail at the associated website. It should be noted, however, that the features used for alignment quality determination are the same as those used for producing the MSA. This is not a very elegant method, but given the nature of IDPs probably the best that can be done. KMAD certainly will emphasize functionally important IDP residues and regions, and thus will provide a basis for subsequent experiments needed to shed light on the sequence structure function relation of this intriguing branch of the protein kingdom.

6 Usage

KMAD is available as a standalone version and as a web-server. The standalone version consists of three parts to (1) obtain information about the features (IDPs, PTMs, SLiMs and domains) and map them onto the sequences; (2) KMAD itself to use all information to align the sequences; and (3) the output scripts. These programs are available with installer, documentation, etc., from the projects website. KMAD accepts a query sequence and runs its whole pipeline automatically to predict disordered regions, align sequences or annotate alignments. The standalone version and the web-server both allow user to change parameters, including user-defined features. A REST API is available, so that users can access KMAD programmatically without the need to install the standalone version.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NewProt project that is funded by the European Commission within its FP7 Programme, under the thematic area KBBE-2011-5 with contract number 289350. Toby Gibson, Des Higgins and David Jones carefully read the manuscript and provided advice.

Funding

National Science Centre HARMONIA 3 [grant no. DEC-2012/06/M/NZ2/00112].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Altschul S., et al. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A., et al. (2008) Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucleic Acids Res., 36(Suppl 1), D419–D425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., et al. (2000) Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet., 25, 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., et al. (2004) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res., 32(Suppl 1), D138–D141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N., et al. (1999) Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol., 294, 1351–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., et al. (2005) Accurate prediction of protein disordered regions by mining protein structure data. Data Min. Knowl. Disc., 11, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkel H., et al. (2013) The eukaryotic linear motif resource ELM: 10 years and counting. Nucleic Acids Res., 42(Database issue), D259–D266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z., et al. (2005) IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics, 21, 3433–3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.C. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.C. (2010) Quality measures for protein alignment benchmarks. Nucleic Acids Res., 38, 2145–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson T.J. (2009) Cell regulation: determined to signal discrete cooperation. Trends Biochem. Sci., 34, 471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. (1982) An improved algorithm for matching biological sequences. J. Mol. Biol., 162, 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iantorno S., et al. (2014) Who watches the watchmen? An appraisal of benchmarks for multiple sequence alignment. Multiple Seq. Align. Methods, 1079, 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving J.A., et al. (2001) Protein structural alignments and functional genomics. Proteins, 42, 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.T. (1999) Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 292, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten H.-J. (2007) 3DM: from data to medicine. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., et al. (2002) MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konagurthu A.S., et al. (2006) MUSTANG: a multiple structural alignment algorithm. Proteins, 64, 559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M.A., et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics, 23, 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linding R., et al. (2003) GlobPlot: exploring protein sequences for globularity and disordery. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 3701–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midic U., et al. (2009) Protein sequence alignment and structural disorder: a substitution matrix for an extended alphabet. In Proceedings of the KDD-09 Workshop on Statistical and Relational Learning in Bioinformatics, ACM, pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Needleman S.B., Wunsch C.D. (1970) A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol., 48, 443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K., Pan Y. (2013) A knowledge-based multiple-sequence alignment algorithm. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform., 10, 884–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C., et al. (2000) T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M.E., et al. (2013) D2P2: database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res., 41(D1), D508–D516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentony M.M., Jones D.T. (2010) Modularity of intrinsic disorder in the human proteome. Proteins, 78, 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrodou E., et al. (2008) A new protein linear motif benchmark for multiple sequence alignment software. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander C., Schneider R. (1991) Database of homology-derived protein structures and the structural meaning of sequence alignment. Proteins, 9, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmeier M., et al. (2007) DisProt: the database of disordered proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 35(Database issue), D786–D793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F., et al. (2011) Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol., 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe I., et al. (2015) CATH: comprehensive structural and functional annotations for genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 43(D1), D376–D381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Uniprot Consortium (2014) Activities at the universal protein resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res., 42(Database issue), D191–D198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., et al. (2005) BAliBASE 3.0: latest developments of the multiple sequence alignment benchmark. Proteins, 61, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lee R., et al. (2014) Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem. Rev., 114, 6589–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venselaar H., et al. (2010) Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics, 11, 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriend G. (1990) WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J. Mol. Graph., 8, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J.J., et al. (2004) Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J. Mol. Biol., 337, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., et al. (2012) SPINE-D: accurate prediction of short and long disordered regions by a single neural-network based method. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 29, 799–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]