Summary

With the current emphasizing primary care specialty, the number of the applicants for anesthesiology residency has declined. In consequence, the medical students’ interest in taking the elective anesthesia clerkship was decreased. Through the program redesign, we have improved our anesthesiology clerkship. In order to attract the best and brightest medical students to choose anesthesiology as a career, continuing efforts to improve both quantity and quality of medical students’ education in anesthesiology are crucial.

Keywords: education, medical; students, medical; anesthesiology, education

Introduction

Recently, the number of medical students applying for anesthesiology residencies has decreased, probably related to declining practice opportunities and current emphasis on primary care specialties. We should encourage medical students to consider anesthesiology as a career by providing a positive learning experience during the anesthesiology clerkship. Recognizing the importance of medical student education, we have improved our anesthesiology clerkship through program redesign and generated increased interest in the clerkship.

Methods

Beginning with the 1993-1994 academic year, we designed a comprehensive new curriculum for our two-week elective basic anesthesiology clerkship for the third- and fourth-year medical students at Stanford University School of Medicine. Whereas the prior program accommodated only one student per two-week period, our restructured program accepted up to five students per two-week period. Lectures were initiated specifically for the medical students with emphasis on preoperative patient preparation, airway management, management of fluid, electrolytes, and acid-base balance, pharmacology and toxicity of local anesthetics, and acute and chronic pain management. In addition, students attended weekly resident-oriented lectures and anesthesia grand rounds. Problem-based learning cases were distributed and discussed throughout the clerkship. Weekly sessions utilizing anesthesia simulators provided interactive, hands-on instruction by faculty members. Each student was assigned for one-week duration to a specific senior resident, who supervised the student in conjunction with a faculty member. The student actively participated in preoperative patient preparation, operating room patient management, and postoperative patient follow up. Each student received a syllabus containing an outline of the clerkship schedule, lecture note, discussion of basic anesthesia principles, and problem-based learning discussion cases.

The anesthesiology clerkship coordinator closely monitored the students’ daily progress. Through exit interviews and questionnaires, feedback was obtained from the students. Through their comments, students contributed significantly to our constant efforts to improve the clerkship. To promote residents’ participation in the education process, an annual resident teaching award was introduced. Based on evaluation by the medical students, a special teaching award was initiated in our department. Interested students were encouraged to elect advanced clerkships in critical care medicine, cardiac anesthesia, obstetric anesthesia, pediatric anesthesia, and pain management and to participate in anesthesia research activities.

Results

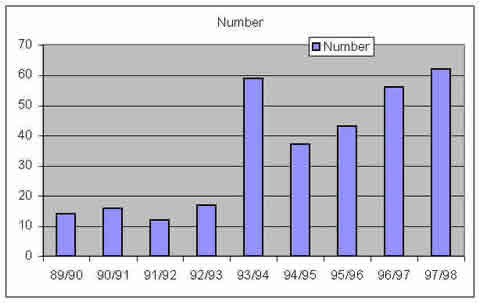

Since our curriculum redesigned at the beginning of the 1993-1994 academic year, the number of medical students in our basic anesthesiology clerkship has increased dramatically (Figure 1). The students have been uniformly enthusiastic about the redesigned program. Many students requested the clerkship because of the positive recommendations of classmates who have completed the rotation. Recently, our clerkship was chosen by a committee of medical students to receive the “High Five Award,” which is given to five top clerkships best demonstrating excellence in medical student education at the School of Medicine.

Figure 1.

Number of students took the anesthesia clerkship at Stanford University Medical Center and Palo Alto Veteran Administration Hospital 1990-1998.

Discussion

Beginning with the 1993-1994 academic year, the marked increase in the number of medical students participating in our elective basic anesthesiology clerkship probably originates from several reasons. One factor is the expansion of our program to accommodate potentially more students. Another factor is our revised curriculum, which is similar to the guidelines for medical student education published by the Society for Education in Anesthesiology (SEA) in 1995.1 Our new redesigned program has generated enthusiastic interest among the medical students. Students have specifically requested our clerkship because of the positive recommendations of classmates. Consequently, our clerkship received the “High Five Award” for excellence in medical student education.

Compared with the 1993-1994 academic year, the number of medical students in our elective anesthesiology clerkship during the 1994-1995 and 1995-1996 academic years demonstrates a relative decrease, which reflects the nationwide trend of declining interest in anesthesiology.2 Reduced practice opportunities for anesthesiologists and prevailing emphasis on primary care specialties have discouraged recruitment, especially since market forces dominate decision-making for graduate medical education.3 With our continuing efforts in improving anesthesiology teaching curriculum, the number of students taking our clerkship have been steadily increased for the past four years. Watts et al further indicated that the positive role model influenced the career choice in anesthesia.4 It is necessary for us to improve the quality of education of trainees and continue attract the highest and best medical students into our specialty.

The elective status of our rotation is not unusual: anesthesiology is a required clerkship in only 21 out of 126 (17%) medical schools in the United States.5 Therefore. It is essential for us to provide a positive educational experience during the anesthesiology clerkships and to promote interest in anesthesiology as a career choice. It is vital to the future of anesthesiology that we increase our efforts to recruit exceptional students into our specialty and optimize the educational process for both medical students and residents.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Ms. Sharon Finnecy for her administrative assistance for the medical students clerkship program and for preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cohen I. Tome J. Teller L. Schwartz J. Society for education in anesthesiology subcommittee report on curriculum guidelines for medical students. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1049. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grogono A. National residency matching program (NRMP) 1998. American Society of Anesthesiologists NEWSLETTER. 1998;62:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longnecker D. Planning the future of anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:495–497. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts R. Marley J. Worley P. Undergraduate education in anaesthesia: the influence of role models on skills learnt and career choice. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1998;26:201–203. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9802600213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varner K. 1997-1998 Curriculum directory. Washington DC: Association of Medical College; 1997. [Google Scholar]