In a phase III pancreatic cancer study, tumor response by positron emission tomography (PET) (exploratory end point) predicted treatment efficacy, including longer overall survival. nab-Paclitaxel/gemcitabine had a significantly higher rate of metabolic response versus gemcitabine. Overall, 5× more patients had a metabolic response by PET compared with RECIST. PET may be a more sensitive measure of response than radiographic modalities.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, positron emission tomography, nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, metabolic response

Abstract

Background

In the phase III MPACT trial, nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (nab-P + Gem) demonstrated superior efficacy versus Gem alone for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. We sought to examine the feasibility of positron emission tomography (PET) and to compare metabolic response rates and associated correlations with efficacy in the MPACT trial.

Patients and methods

Patients with previously untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas were randomized 1:1 to receive nab-P + Gem or Gem alone. Treatment continued until disease progression by RECIST or unacceptable toxicity.

Results

PET scans were carried out on the first 257 patients enrolled at PET-equipped centers (PET cohort). Most patients (252 of 257) had ≥2 PET-avid lesions, and median maximum standardized uptake values at baseline were 4.6 and 4.5 in the nab-P + Gem and Gem-alone arms, respectively. In a pooled treatment arm analysis, a metabolic response by PET (best response at any time during study) was associated with longer overall survival (OS) (median 11.3 versus 6.9 months; HR, 0.56; P < 0.001). Efficacy results within each treatment arm appeared better for patients with a metabolic response. The metabolic response rate (best response and week 8 response) was higher for nab-P + Gem (best response: 72% versus 53%, P = 0.002; week 8: 67% versus 51%; P = 0.014). Efficacy in the PET cohort was greater for nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone, including for OS (median 10.5 versus 8.4 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; P = 0.009) and ORR by RECIST (31% versus 11%; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Pancreatic lesions were PET avid at baseline, and the rate of metabolic response was significantly higher for nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone at week 8 and for best response during study. Having a metabolic response was associated with longer survival, and more patients experienced a metabolic response than a RECIST-defined response.

ClinicalTrials.gov

introduction

Pancreatic cancer bears an extremely poor prognosis as evidenced by the only 20% of patients who survive ≥1 year after diagnosis [1]. Thus, it is crucial to identify early markers of treatment efficacy. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, a technique that uses radioactively labeled glucose 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), has been used for the study of cancer, as both a diagnostic tool and, increasingly, as a measure of tumor response to treatment [2–8]. Compared with conventional radiographic means of gauging tumor response based on diameter, metabolic response by PET may represent a more functional measure of tumor response or progression by directly assessing the degree of metabolic activity [6, 9].

Tumor response measured by computed tomography (CT) scan has been shown to predict patient survival in metastatic solid tumors [10], and PET may serve as a complement or improvement in this regard or as a surrogate modality if CT is contraindicated. For example, a change from baseline in the tumor uptake of 18F-FDG during treatment may be a predictive marker of survival in gastric cancer [11]. Although PET imaging has been validated as a marker of therapeutic efficacy in some cancers, such as lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, and melanoma [3, 4, 11–14], the potential of PET as a marker of efficacy in pancreatic cancer is still under investigation. However, recent results confirm that pancreatic lesions do take up 18F-FDG (i.e. PET-avid) and can be imaged using PET technology [15].

The correlation between metabolic response and efficacy was evaluated in a phase I/II trial in which patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer were treated with nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) plus gemcitabine (Gem) [16]. Patients who were treated at the maximum tolerated dose of 125 mg/m2 (n = 44) demonstrated an overall response rate [ORR; by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0] of 48% and a median overall survival (OS) of 12.2 months [16]. All patients had a metabolic response by PET as defined by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; defined in methods of this report) [16]. Patients who experienced a complete metabolic response (31%) had a significantly longer OS compared with patients who experienced an incomplete metabolic response (median 20.1 versus 10.3 months; P = 0.01).

The promising efficacy results from the phase I/II trial led to a large phase III trial (MPACT; N = 861), which demonstrated superior efficacy for nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone for all efficacy end points including OS [median: 8.7 versus 6.6 months; hazard ratio (HR), 0.72; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62–0.83; P < 0.001] and independently assessed ORR (23% versus 7%; P < 0.001) [17, 18]. Evaluation of tumor response by PET was included as an exploratory objective in the MPACT protocol based on the positive findings from the phase I/II trial described above.

patients and methods

The study design was described previously [18].

patients

Patients were required to have measurable (RECIST version 1.0) metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Additional eligibility criteria included a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥70 and bilirubin ≤upper limit of normal. Prior chemotherapy in the adjuvant [except 5-fluorouracil or Gem as a radiation sensitizer] or metastatic setting was not allowed.

study design

Patients were randomized 1:1 (stratified by KPS, presence of liver metastases, and geographic region) to receive nab-P 125 mg/m2 plus Gem 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days for 56 days or Gem alone 1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 36, and 43 every 56 days (cycle 1) and then on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days (cycle ≥2). Treatment continued until disease progression by RECIST or unacceptable toxicity.

patient population

All patients who had a baseline PET measurement were included in the PET cohort. Some analyses were based on metabolic response at week 8 or 16 or best response during study.

assessments

Tumor response was evaluated every 8 weeks by spiral CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and graded according to RECIST version 1.0. PET/CT scans were carried out in a cohort of the first-enrolled patients at PET-equipped cancer centers at baseline, week 8, and week 16 (68 patients underwent PET imaging beyond week 16), and evaluated according to EORTC criteria [6]. A complete metabolic response was defined as complete resolution of 18F-FDG uptake; a partial metabolic response was defined as a reduction in 18F-FDG standardized uptake value (SUV) ≥15%–25% after 1 cycle of treatment or >25% after ≥2 cycles of treatment. Additional description of PET imaging, as well as the imaging charter for the MPACT study (supplementary Material S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), includes detailed information on imaging by CT, MRI, and PET.

Treatment-related adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

results

characteristics of the PET cohort

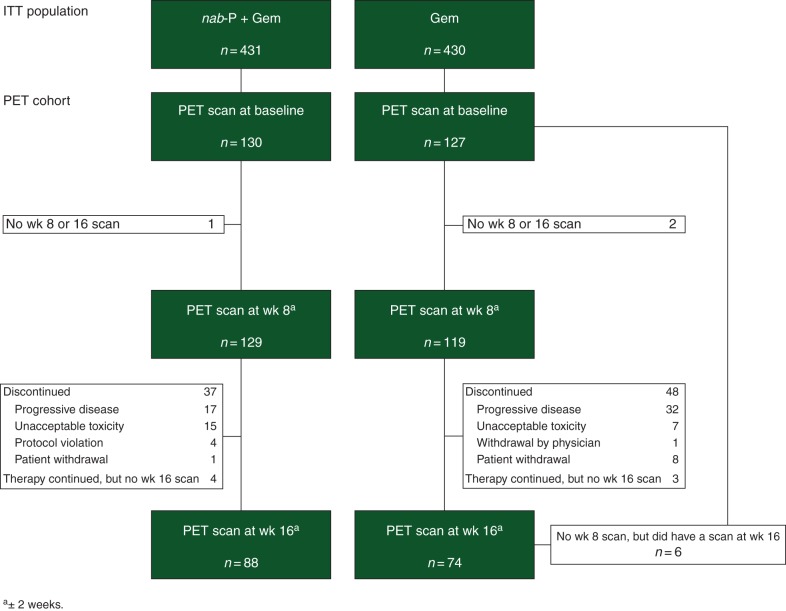

PET/CT scans were carried out in 79 study sites in 257 patients at baseline (1–8 patients per center; 165 in North America, 49 in Australia, and 43 in Eastern Europe), 248 at week 8, and 162 at week 16 (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics between the two treatment arms were balanced within the PET cohort and similar to the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Forty-five percent of patients were 65 years of age or older, two thirds of patients had a KPS of 90 or 100, and 41% of patients had ≥3 sites of metastasis (identified by radiologic imaging). Within the PET cohort, the rates of secondary therapy for patients whose disease progressed during treatment were 52% for nab-P + Gem and 56% for Gem alone. At baseline, 74% of patients had ≥3 PET-avid tumors [(primary or metastatic) median, 5.0 lesions per patient in each treatment arm]. The baseline median maximum SUV (SUVmax) was 4.6 for the nab-P + Gem arm and 4.5 for the Gem-alone arm (mean ± standard deviation: 4.8 ± 1.9 for nab-P + Gem and 5.2 ± 2.9 for Gem alone).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients who received PET scans. Gem, gemcitabine; ITT, intent-to-treat; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel; PET, positron emission tomography.

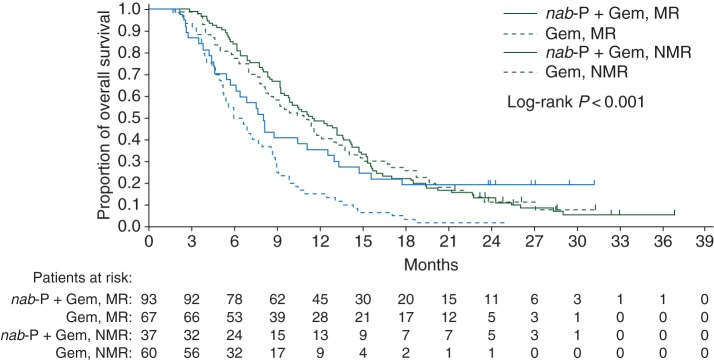

efficacy analyses based on best PET response throughout study

In a pooled analysis of both treatment arms, patients with a metabolic response [complete (CMR) or partial (PMR)] at any time during the study had a significantly longer OS than patients without one (median 11.3 versus 6.9 months; HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.42–0.74; P < 0.001). Note that analyses throughout this report are based on grouping CMR and PMR because of the small number of patients with a CMR [11/130 (8%) in the nab-P + Gem arm and 3/127 (2%) in the Gem arm]. In the nab-P + Gem arm, ORR by RECIST was significantly better for patients who experienced a metabolic response compared with patients who did not; the effects on progression-free survival (PFS) and OS did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.110 and 0.464, respectively; Table 1). The association of metabolic response with efficacy was similar for the Gem-alone arm with significant differences observed for ORR, PFS, and OS (Table 1). Kaplan–Meier curves of survival within each treatment arm based on metabolic response are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Efficacy as a function of best PET response

| Efficacy |

nab-P + Gem |

Gem |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET response |

RRR or HRa (95% CI) | P value | PET response |

RRR or HRa (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Yes (N = 93) | No (N = 37) | Yes (N = 67) | No (N = 60) | |||||

| ORR by RECIST | 37% | 16% | 2.3 (1.03–4.92) | 0.023 | 18% | 3% | 5.4 (1.25–23.04) | 0.009 |

| Median PFS | 7.5 months | 5.3 months | 0.63 (0.36–1.11) | 0.110 | 5.6 months | 3.6 months | 0.39 (0.24–0.66) | <0.001 |

| Median OS | 11.5 months | 8.0 months | 0.85 (0.54–1.32) | 0.464 | 10.9 months | 6.3 months | 0.43 (0.29–0.65) | <0.001 |

aRRR = ORRPET response/ORRno PET response; HR = HRPET response/no PET response.

Gem, gemcitabine; HR, hazard ratio; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; RRR, response rate ratio.

Figure 2.

Overall survival in each treatment arm based on metabolic response. Gem, gemcitabine; MR, metabolic response; nab-P, nab-paclitaxel; NMR, no metabolic response.

landmark efficacy analyses based on PET response at week 8 or 16

In a week-8 pooled analysis of the PET cohort, the metabolic response rate was 60% (146/245), whereas the ORR by RECIST (measured by CT) was 11% (27/245). Of the 146 patients with a metabolic response by PET, 14% had an objective response, 81% had stable disease, and 5% had progressive disease by RECIST (Table 2). The longest median OS was observed in patients (n = 20) with both a metabolic response and an objective response by RECIST (13.5 months; Table 3). However, the median OS for the 126 patients with a metabolic response in the absence of a response by RECIST was >3 months longer than in patients with neither type of tumor response (n = 92; 10.2 versus 6.9 months, respectively). The small set of patients (n = 7) who did not experience a metabolic response by PET but did have a response by RECIST had a median OS of 10.4 months.

Table 2.

Tumor response by RECIST versus metabolic response by PET at week 8: pooled treatment arm analysis

| Outcome | CMR or PMR by PET (N = 146) | SD by PET (N = 24) | PD by PET (N = 66) | PET response unevaluable (N = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR or PR by RECIST, n (%) | 20 (8) | 1 (<1) | 5 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| SD by RECIST, n (%) | 118 (48) | 21 (9) | 48 (20) | 6 (2) |

| PD by RECIST, n (%) | 8 (3) | 2 (<1) | 12 (5) | 2 (<1) |

| RECIST response unevaluable, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 |

CR, complete response; CMR, complete metabolic response; PD, progressive disease; PET, positron emission tomography; PMR, partial metabolic response; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease.

Table 3.

Survival as a function of RECIST and PET response at week 8

| Complete or partial response by RECIST |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes |

No |

||||

| N | Median OS (months) | N | Median OS (months) | ||

| Complete or partial MR | Yes | 20 | 13.5 | 126 | 10.2 |

| No | 7 | 10.4 | 92 | 6.9 | |

MR, metabolic response; OS, overall survival; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors.

At week 8, 86 of 129 patients (67%) in the nab-P + Gem arm had a metabolic response versus 61 of 119 patients (51%) in the Gem-alone arm (P = 0.014). A pooled analysis revealed that patients with a metabolic response at week 8 had a significantly longer OS than those without a metabolic response at week 8 (median 10.5 versus 7.3 months; HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.51–0.91; P = 0.008). Patients with a metabolic response also appeared to have longer OS than patients without a metabolic response within each treatment arm (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

At week 16, 54 of 88 patients (61%) in the nab-P + Gem arm had a metabolic response versus 26 of 74 patients (35%) in the Gem-alone arm (P < 0.001). OS benefits were also revealed for patients with a metabolic response versus those without one at week 16 in the pooled group (median 14.2 versus 9.2 months; HR 0.55; 95% CI 0.39–0.78; P < 0.001) and within treatment arms (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Findings for PFS and ORR at weeks 8 and 16 based on PET response were consistent with OS findings (supplementary Tables S2–S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

results by treatment arm in the PET cohort

The median percent reductions in SUVmax from baseline at weeks 8 and 16 were both greater for nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone (39.7% versus 27.6% and 44.1% versus 23.2%, respectively; supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). These reductions translated to significantly higher metabolic response rates for nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone (best response during study: 72% versus 53%, P = 0.002; week 8: 67% versus 51%, P = 0.014; week 16: 61% versus 35%; P < 0.001).

The median follow-up times in the PET cohort for nab-P + Gem and Gem-alone arms were 9.2 and 9.1 months, respectively, for PFS and 28.6 and 26.2 months for OS. nab-P + Gem demonstrated a higher ORR (31% versus 11%; response rate ratio, 2.79; 95% CI 1.60–4.87; P < 0.001) and longer PFS (median, 6.7 versus 4.3 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI 0.44–0.86; P = 0.004) and OS (median, 10.5 versus 8.4 months; HR, 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.92; P = 0.004) versus Gem alone in the PET cohort. No new safety signals were observed in the PET cohort.

discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of patients (n = 257) with pancreatic cancer to be evaluated by PET in a single prospective trial. The median SUVmax (4.6 and 4.5 in the nab-P + Gem and Gem-alone arms, respectively) and high percentage of patients with ≥3 PET-avid lesions at baseline (74%) demonstrate that PET imaging is feasible for response evaluation in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, metabolic response was associated with longer survival regardless of treatment, and the rate of metabolic response by PET was significantly higher for patients who received nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone: ∼30% more patients achieved a metabolic response at any time during the study (similar difference at week 8), and twice as many patients had a metabolic response at week 16. In addition, the treatment difference favoring nab-P + Gem for OS, PFS, and ORR in the ITT population [17, 18] was also evident in the PET cohort.

Metabolic response rates at week 8 were similar to best metabolic response rates during the study, indicating that PET is a useful early predictor of the treatment outcome. Determining that a given treatment is ineffective at an early time point may allow either optimization of an existing regimen or a switch to a different, potentially more effective treatment. Thus, sensitive markers of tumor response are of great value. In the PET cohort of the MPACT study, the rate of metabolic response by EORTC criteria at week 8 was substantially higher than the ORR by RECIST (67% versus 30% for nab-P + Gem and 51% versus 10% for Gem alone), suggesting that metabolic response by PET may be the more sensitive measure of tumor response. PET may more effectively measure subtle changes in tumors. For example, an effective treatment might induce a necrotic core in the interior of a large tumor, which would be apparent by PET, but not necessarily by a CT scan. Although it is beyond the scope of the current analysis, understanding the association between tumor biology and likelihood of achieving a metabolic response may warrant further study.

PET imaging may provide useful information to supplement radiologic findings in guiding treatment decisions in pancreatic cancer. Evaluation of OS based on response by RECIST and metabolic response by PET at week 8 revealed that patients with both types of response experienced the longest OS, and patients with neither type of response had the worst OS. Patients with only one type of response had similar median OS values; however, 126 patients had a metabolic response only versus 7 patients with a RECIST response only. The median OS was >3 months longer for patients with a metabolic response only than for patients who did not experience a response by either measure, suggesting that metabolic response may predict a degree of treatment benefit, even in the absence of a tumor response by RECIST (Table 3). Importantly, this study confirms the overall association of a PET metabolic response with OS as observed in the phase I/II study [16].

The metabolic response rate in this study was based primarily on follow-up scans at week 8 (end of cycle 1) or 16. Whether metabolic responses might have been observed at an earlier time point is an interesting question. In gastrointestinal stromal tumor studies, a metabolic response 4 weeks after the initiation of therapy was predictive of tumor response [13, 19]; in some forms of gastric cancer, a metabolic response as early as 2 weeks into treatment was predictive of the clinical outcome [13, 19]. Recent methods for PET imaging that were optimized for early prediction of clinical outcomes should be tested to augment the promising findings of this study [10, 20].

In summary, patients who achieve a metabolic response appear to have good clinical outcomes, regardless of treatment. PET imaging for measuring tumor response in this setting was feasible early (week 8) and predicted treatment efficacy, including longer survival. In addition, the PET response data were consistent with other efficacy data in MPACT; significantly more patients receiving nab-P + Gem versus Gem alone had a metabolic response. Patients without a metabolic response receiving nab-P + Gem had better outcomes than patients without a metabolic response who received Gem alone. Furthermore, at week 8, metabolic response by PET was observed in a 5× higher proportion of patients than RECIST-defined response, indicating that it may be a more sensitive measure of tumor response than radiographic modalities. If validated in other studies, its use may help optimize patient care by allowing a more rapid identification of potentially efficacious treatments and facilitates in treatment decision.

additional quality assurance metrics

The mean duration of FDG uptake before scanning was 67.4 min at baseline, 68.6 min at week 8, and 67.3 min at week 16. The mean difference per patient from baseline to week 8 was 1 min (standard deviation = 12.4), and the mean difference from baseline to week 16 was 0.3 min (standard deviation = 12.5).

statistical methods

Efficacy analyses in the overall population were based on the ITT population (all randomized patients). The primary end point was OS, which was defined as the duration from randomization in the trial to the time of death. Secondary end points included PFS, defined as the duration from randomization to disease progression by RECIST or death, and ORR by independent evaluation.

OS and PFS were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier methods. OS and PFS data were censored in cases of ongoing follow-up at study closure or lost follow-up. PFS data were also censored for the following reasons: scanning discontinued on disease progression per investigator, no postbaseline assessment, initiation of subsequent therapy, or two or more consecutive missing scans followed by a PFS event.

Analysis of PET findings was a predefined exploratory end point; as an exploratory end point, the sample size was not specifically planned to allow statistical comparisons of PET data. All patients enrolled at PET-equipped centers were to be evaluated by PET until a protocol amendment specified that subsequently enrolled patients would not undergo PET imaging due to logistical constraints and cost considerations. The PET cohort was defined as the set of patients who received a PET/CT scan at baseline. Analyses were based on best PET response at week 8 or 16 (±2 weeks) or best PET response throughout treatment.

SAS version 9.1 software was used for all statistical comparisons. All P values were two-sided, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

funding

Funding for this study was provided by Celgene Corporation (no grant number).

disclosure

RKR: consultant or advisory role, honoraria, and research funding, Celgene Corporation; DG: consultant or advisory role and research funding, Celgene Corporation; RLK: research funding, Celgene Corporation; FPA: research funding Clinical Research Alliance and Celgene Corporation; MM, SS, and LT: research funding, Celgene Corporation; JT: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Celgene Corporation; J-LVL: research funding, Celgene Corporation; HL, DM, and BL: employment and stock ownership, Celgene Corporation; DDVH: consultant or advisory role, honoraria, and research funding, Celgene Corporation.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

Writing assistance was provided by John R. McGuire, MediTech Media, LLC and funded by Celgene Corporation. Biostatistical support was provided by Peng Chen, Celgene Corporation. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions for this manuscript.

references

- 1.American Cancer Society, ed. Cancer Facts and Figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015; No. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood KA, Hoskin PJ, Saunders MI. Positron emission tomography in oncology: a review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007; 19(4): 237–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selzner M, Hany TF, Wildbrett P et al. Does the novel PET/CT imaging modality impact on the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer of the liver? Ann Surg 2004; 240(6): 1027–1034; discussion 1035–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borst GR, Belderbos JS, Boellaard R et al. Standardised FDG uptake: a prognostic factor for inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41(11): 1533–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reske SN, Grillenberger KG, Glatting G et al. Overexpression of glucose transporter 1 and increased FDG uptake in pancreatic carcinoma. J Nucl Med 1997; 38(9): 1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET study group. Eur J Cancer 1999; 35(13): 1773–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, ed. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Pancreatic Adeocarcinoma, Version 2.2014. 1.2014th edition The National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2014. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, ed. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; No. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eschmann SM, Friedel G, Paulsen F et al. Is standardised (18)F-FDG uptake value an outcome predictor in patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006; 33(3): 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piessevaux H, Buyse M, Schlichting M et al. Use of early tumor shrinkage to predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(30): 3764–3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott K, Herrmann K, Lordick F et al. Early metabolic response evaluation by fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography allows in vivo testing of chemosensitivity in gastric cancer: long-term results of a prospective study. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(7): 2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haioun C, Itti E, Rahmouni A et al. [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in aggressive lymphoma: an early prognostic tool for predicting patient outcome. Blood 2005; 106(4): 1376–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoch G, Kanja J, Bauer S et al. Comparison of PET, CT, and dual-modality PET/CT imaging for monitoring of imatinib (STI571) therapy in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Nucl Med 2004; 45(3): 357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, de Castro Faria S et al. CT evaluation of the response of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after imatinib mesylate treatment: a quantitative analysis correlated with FDG PET findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(6): 1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi HJ, Kang CM, Lee WJ et al. Prognostic value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Yonsei Med J 2013; 54(6): 1377–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(34): 4548–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107(2): doi:10.1093/jnci/dju413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(18): 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prior JO, Montemurro M, Orcurto MV et al. Early prediction of response to sunitinib after imatinib failure by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(3): 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu AJ, Goodman KA. Positron emission tomography imaging for gastroesophageal junction tumors. Semin Radiat Oncol 2013; 23(1): 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.