Abstract

Background

Prematurity is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality amongst non-anomalous neonates in the United States. Intramuscular 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP-C) injections reduce the risk of recurrent prematurity by approximately one third. Unfortunately, prophylactic 17OHP-C is not always effective, and one-third of high-risk women will have a recurrent PTB despite 17OHP-C therapy. The reasons for this variability in response are unknown. Previous investigators have examined the influence of a variety of factors on 17OHP-C response, but have analyzed data used a fixed outcome of ‘term’ delivery to define progesterone response.

Objective

We hypothesized that the demographics, history, and pregnancy course among women who deliver at a similar gestational age with 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP-C) for recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) prevention differs when compared to those women who deliver later with 17OHP-C, and that these associations could be refined by using a contemporary definition of 17OHP-C ‘responder.’

Study Design

This was a planned secondary analysis of a prospective, multi-center, longitudinal study of women with ≥ 1 prior documented singleton SPTB <37 weeks gestation. Data were collected at 3 pre-specified gestational age epochs during pregnancy. All women included in this analysis received 17OHP-C during the studied pregnancy. We classified women as a 17OHP-C responder or non-responder by calculating the difference in delivery gestational age between the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy and her earliest SPTB. Responders were defined as those with pregnancy extending ≥3 weeks later with 17OHP-C compared to the delivery gestational age of their earliest prior SPTB. Data were analyzed using chi-square, t-test, and logistic regression.

Results

155 women met inclusion criteria. The 118 responders delivered later on average (37.7 weeks) than the 37 non-responders (33.5 weeks), p<0.001. Among responders, 32% (38/118) had a recurrent SPTB. Demographics (age, race/ethnicity, education, and parity) were similar between groups. In the regression model, the gestational age of the prior SPTB (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.56–0.82, p<0.001), vaginal bleeding/abruption in the current pregnancy (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.06–0.88, p=0.031), and first-degree family history of SPTB (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.88, p=0.024) were associated with response to 17OHP-C. Because women with a penultimate preterm pregnancy were more likely to be 17OHP-C non-responders, we performed an additional limited analysis examining only the 130 women whose penultimate pregnancy was preterm. In regression models, the results were similar to those in the main cohort.

Conclusions

Several historical and current pregnancy characteristics define women at risk for recurrent PTB at a similar gestational age despite 17OHP-C therapy. These data should be prospectively studied in larger cohorts and combined with genetic and environmental data to identify women most likely to benefit from this intervention.

Keywords: decidual hemorrhage, progesterone supplementation, recurrent preterm birth, spontaneous preterm labor

Introduction

Although the rate of preterm birth (PTB) in the United States has fallen slightly in recent years, the proportion of babies born preterm remains unacceptably high at 11.4% (2013).1 Whereas a portion of PTB are for medical and/or fetal indications, the majority fall in to the broad classification of spontaneous PTB (SPTB) and includes deliveries due to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), cervical insufficiency, and idiopathic preterm labor.2 SPTB recurs in 35–50% of women, and tends to recur at similar gestational ages.3–5 The probability of SPTB also increases with the number of prior SPTB a woman has experienced, with the most recent birth being the most predictive.4,6

When administered weekly beginning in the mid-trimester, intramuscular 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP-C) injections reduce the risk of recurrent prematurity by approximately one third.7 Unfortunately, prophylactic 17OHP-C is not always effective, and one-third of high-risk women will have a recurrent PTB despite 17OHP-C therapy. The reasons for this variability in response are unknown. It has been hypothesized that genetic factors may influence response, and limited studies have found associations between genetic variation in the progesterone receptor and nitric oxide genes and clinical response to 17OHP-C.8,9

Traditionally, prematurity prevention studies have defined ‘success’ as achieving a predetermined gestational age threshold. Typically, deliveries <37 weeks are regarded as ‘preterm,’ whereas those <34 or <32 weeks are regarded as ‘early preterm,’ and those <28 weeks defined as ‘very preterm.’ Given that SPTB tends to recur at similar gestational ages, the definition of successful treatment with 17OHP-C may be more appropriately defined by the difference in delivery gestational age in women receiving 17OHP-C, rather than using strict gestational age threshold cutoffs. There is a significant reduction in neonatal morbidity, mortality, and costs of care with pregnancy prolongation; ignoring this fact may result in an underestimation of the beneficial effect of 17OHP-C prophylaxis.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate maternal background, past pregnancy characteristics, and antenatal factors among a cohort of women followed longitudinally and receiving 17OHP-C for recurrent PTB prevention. We hypothesized that demographics, history, and pregnancy course differ between women who deliver at a similar gestational age with 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17OHP-C) for recurrent spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) prevention compared to those women who deliver later with 17OHP-C.

Materials and Methods

This is a planned analysis of a multicenter, prospectively collected longitudinal study of women enrolled in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Genomic and Proteomic Network for Preterm Birth Research. Briefly, women with a history of a prior documented singleton spontaneous preterm birth between 20 weeks 0 days gestation and 36 weeks 6 days gestation were recruited across eight clinical sites from November 2007 through January 2011 and followed prospectively. All women had an initial study visit between 10 weeks 0 days – 18 weeks 6 days gestation. Gestational age was determined by a combination of last menstrual period (if available) and ultrasound. As all patients enrolled less than 19 weeks, the gestational age was assigned by ultrasound if the ultrasound dating varied by +/− 7 days from the last menstrual period.

Clinical and demographic data were collected by trained research nurses. Data were collected at 2 additional pre-specified return visits (visit 2: 18 weeks 0 days – 23 weeks 6 days and visit 3: 28 weeks 0 days – 31 weeks 6 days) and at delivery. Additional data were collected if an enrolled participant was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of preterm labor or PPROM. Research nurses conducted in-person interviews with participants during study visits and abstracted additional clinical and demographic data from medical records. Data collected included demographics, medical, social, family, and obstetric histories, obstetric course and complications during the current pregnancy (including intrapartum course, mode of delivery, and neonatal outcomes). Obstetric management was per each woman’s primary obstetric provider. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

For the purposes of this analysis, we included only women who received at least one dose of 17OHP-C during pregnancy for the prevention of recurrent PTB. We classified women as a 17OHP-C responder or non-responder by calculating the difference in the gestational age at delivery between the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy and her earliest SPTB, as we have previously described.8 Specifically, the difference between the earliest delivery gestational age due to SPTB and the delivery gestational age with 17OHP-C was calculated, and termed the ‘17OHP-C effect.’ Women with a 17OHP-C effect of +3 weeks or greater (i.e., the individual’s pregnancy or pregnancies treated with 17OHP-C delivered at least 3 weeks later compared to the gestational age of the earliest SPTB without 17OHP-C treatment) were considered 17OHP-C responders. Women with a negative overall 17OHP-C effect and those with an overall 17OHP-C effect of <3 weeks were classified as non-responders. Women with a 17OHP-C effect of <3 weeks but delivering at term (e.g. if the ‘earliest’ prior SPTB was at 35 weeks, and the patient delivered during the 17OHP-C treated pregnancy at 37 weeks) were considered ‘equivocal’ 17OHP-C responders and were excluded from analysis.

Univariable analyses were conducted by using chi-square, t-test, and ANOVA as appropriate. Multivariable analysis performed by using stepwise backward elimination logistic regression, and factors with p<0.20 remained in final models. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1 (College Station, TX). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

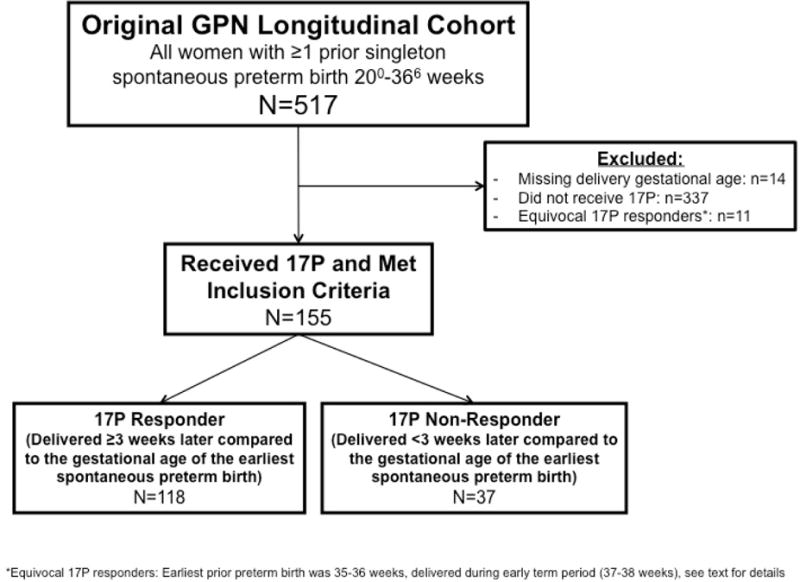

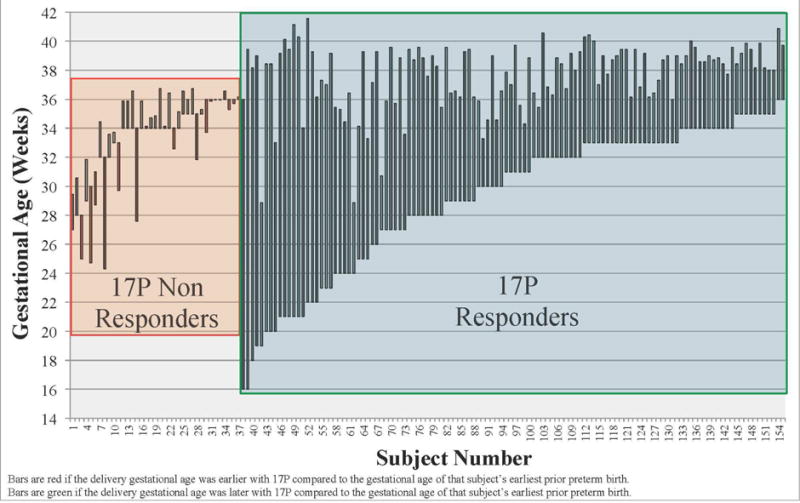

From the original cohort of 517 women, 166 (33.0%) received at least one dose of 17OHP-C and met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Eleven women had a 17OHP-C effect <3 yet delivered at term because their earliest prior PTB was more than 34 weeks gestation; these women were considered ‘equivocal’ responders and were excluded. Of the remaining women, 118/155 (76%) delivered at least 3 weeks later compared to the delivery gestational age of their previous earliest PTB and were considered 17OHP-C responders, and 37 (24%) had a 17OHP-C effect <3 and were considered non-responders. The 118 responders delivered later on average (37.7 weeks) than the 37 non-responders (33.5 weeks), p<0.001. Although 32% of responders (38/118) had a recurrent SPTB, they were considered responders because they delivered ≥3 weeks later compared to their earliest SPTB. The gestational age of the earliest prior PTB and the delivery gestational age of the current studied pregnancy with 17OHP-C are plotted for each subject in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Study enrollment.

Figure 2.

The gestational age of the earliest prior PTB and the delivery gestational age of the current studied pregnancy with 17OHP-C are plotted for each subject.

Demographic characteristics were similar between responders and non-responders (Table 1). Characteristics of the prior pregnancy were also similar, with some notable differences. Although the gestational age of their earliest prior SPTB was later, and a similar proportion had a history of a prior term delivery, non-responders were more likely to have delivered their penultimate pregnancy preterm (Table 1). They were also more likely to have either a mother or sister with a history of a preterm birth less than 37 weeks gestation (Table 1). Women who did not respond to 17OHP-C were more likely to have one or more episodes of vaginal bleeding during pregnancy or be diagnosed with a clinical abruption (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic factors and prior pregnancy history by 17OHP-C responder status.

| 17OHP – C – non-responder (n=37) | 17OHP – C responder (n=118) | P – value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age (mean, +/− SD) | 27.0 +/− 4.9 | 27.7 +/− 5.1 | 0.470 |

|

| |||

| Maternal race | |||

| Caucasian | 24 (64.9) | 72 (61.0) | 0.803 |

| African-American | 12 (32.4) | 39 (33.1) | |

| Other | 1 (2.7) | 7 (5.9) | |

|

| |||

| Maternal Hispanic ethnicity | 3 (8.1) | 18 (15.3) | 0.268 |

|

| |||

| High school education or higher | 29 (78.4) | 89 (75.4) | 0.713 |

|

| |||

| Insurance status | |||

| Public | 16 (43.2) | 62 (52.5) | 0.070 |

| Private | 20 (54.1) | 46 (39.0) | |

| Self-pay | 1 (2.7) | 10 (8.5) | |

|

| |||

| Gestational age of earliest prior spontaneous preterm birth (mean, +/− SD) | 33.5 +/− 2.4 | 29.2 +/− 5.0 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Number of prior spontaneous preterm births (mean, +/− SD) | 1.5 +/− 0.7 | 1.6 +/− 1.0 | 0.531 |

|

| |||

| More than one prior spontaneous preterm birth | 19 (51.4) | 42 (35.6) | 0.087 |

|

| |||

| History of a spontaneous preterm birth in the penultimate pregnancy reaching at least 20 weeks gestation | 35 (94.6) | 95 (80.5) | 0.042 |

|

| |||

| One or more previous term birth(s) | 14 (37.8) | 39 (33.1) | 0.590 |

|

| |||

| History of abruption | 3 (8.1) | 2 (1.7) | 0.054 |

|

| |||

| History of preterm premature rupture of membranes in one or more prior pregnancies, 20–37 weeks gestation | 5 (13.5) | 13 (11.0) | 0.679 |

|

| |||

| Sister and/or mother with preterm birth | 19 (51.4) | 38 (32.2) | 0.035 |

Data are n(%) unless specified.

Table 2.

Current pregnancy factors by 17OHP-C responder status. Data are n(%) unless specified.

| 17OHP – C – non responder (n=37) | 17OHP – C responder (n=118) | P – value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2), mean +/− SD | 25.9 +/− 6.3 | 27.5 +/− 7.3 | 0.251 |

|

| |||

| Smoked during pregnancy | 3 (8.1) | 8 (6.7) | 0.784 |

|

| |||

| One or more episode(s) of vaginal bleeding or diagnosis of clinical abruption | 7 (18.9) | 9 (7.6) | 0.049 |

|

| |||

| Bacterial vaginosis | 4 (10.8) | 17 (14.4) | 0.577 |

|

| |||

| Gonorrhea and/or chlamydia | 2 (5.4) | 10 (8.5) | 0.542 |

|

| |||

| Short cervix <2.50cm* | 3 (8.1) | 9 (7.6) | 0.924 |

|

| |||

| Patient reported regular contractions at time of routine outpatient followup appointment | 17 (46.0) | 35 (30.2) | 0.078 |

|

| |||

| Received any tocolysis | 16 (43.2) | 34 (28.8) | 0.101 |

| Received indomethacin | 4 (10.8) | 7 (5.9) | 0.313 |

| Received magnesium sulfate | 3 (8.1) | 13 (11.0) | 0.612 |

| Received nifedipine | 14 (37.8) | 21 (17.8) | 0.011 |

|

| |||

| Received antenatal corticosteroids | 19 (51.4) | 26 (22.0) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Male fetus | 23 (62.2) | 58 (49.2) | 0.167 |

among 95 women with transvaginal cervical length assessment

Of note, women with a prophylactic cervical cerclage were excluded from enrollment in the main study. However, six women underwent cerclage placement because of cervical shortening or cervical dilation, identified by either physical or ultrasound examination, and all were classified as 17OHP-C responders. These 6 women delivered at a mean 35.5 weeks gestation (range 28.9–39.6 weeks). No study participant was noted to also be taking vaginal progesterone in the second trimester, although 7 women (3 non-responders and 4 responders, p=0.196) were prescribed first trimester supplementation at the discretion of their primary obstetric care provider.

In the regression model, each additional week gestation of the earliest prior SPTB (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.56–0.82, p<0.001), vaginal bleeding/abruption in the current pregnancy (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.06–0.88, p=0.031), and first-degree family history of SPTB (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.88, p=0.024) were associated with response to 17OHP-C (Table 3). Other factors considered in the initial model but removed from final models due to p>0.20 included a history of abruption in a prior pregnancy, insurance status, and a male fetus.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Shown are factors associated with 17OHP-C response in the overall cohort of 155 women.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p – value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age of earliest prior spontaneous preterm birth, week | 0.68 | 0.56–0.82 | <0.001 |

| First degree family history of spontaneous preterm birth | 0.37 | 0.15–0.88 | 0.024 |

| Vaginal bleeding or abruption in current pregnancy | 0.24 | 0.06–0.88 | 0.031 |

| Immediately antecedent pregnancy delivered preterm <37 weeks | 0.21 | 0.03–1.19 | 0.079 |

Because women with a penultimate preterm pregnancy were more likely to be 17OHP-C non-responders, we performed an additional limited analysis examining only the 130 women whose penultimate pregnancy was preterm. Using the definition of 17OHP-C responder as described above, 95/130 (73.1%) women were considered 17OHP-C responders, and 35/130 (26.9%) were non-responders. The antecedent delivery gestational age remained earlier among the group classified as responders (30.6 +/− 4.5 vs. 33.9 +/− 2.4, p<0.001); other baseline and demographic characteristics were also similar between groups (data not shown). In regression models, the results were similar to those in the main cohort (Table 4)., In order to further assess the impact of the delivery gestational age of the penultimate pregnancy, we used the gestational age of the penultimate pregnancy (instead of the gestational age of the earliest PTB) to calculate the 17OHP-C effect as described in the methods. This classified 86/130 women (66.2%) as 17OHP-C responders, 41/130 (31.5%) as 17OHP-C non-responders, and 3/130 (2.3%) as equivocal 17OHP-C responders. Again, the gestational age of the earliest prior PTB was earlier among 17OHP-C responders (29.6 +/− 2.9 vs. 32.5 +/− 3.8, p=0.001). Overall regression models remained similar using this modified definition of 17OHP-C responder, with later gestational age of the earliest prior PTB and positive family history both reducing the odds of 17OHP-C response, although the presence of vaginal bleeding or abruption did not remain associated with 17OHP-C response in this final model.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model. Shown are factors associated with 17OHP-C response among the 130 women with a penultimate preterm birth.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p – value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age of earliest prior spontaneous preterm birth, week | 0.68 | 0.56–0.83 | <0.001 |

| First degree family history of spontaneous preterm birth | 0.49 | 0.20–1.23 | 0.130 |

| Vaginal bleeding or abruption in current pregnancy | 0.39 | 0.09–1.57 | 0.183 |

| History of abruption in one or more prior pregnancies | 0.11 | 0.01–1.46 | 0.094 |

Finally, in order to assess whether women with very early prior PTB had different factors associated with significant pregnancy prolongation, a second limited subgroup analysis was performed. Of 69 women with an earliest prior PTB <32 weeks gestation, 63 (91.3%) delivered at least 3 weeks later when administered 17OHP-C. All 6 women who did not experience significant pregnancy prolongation had an antecedent PTB; 2/6 had vaginal bleeding or abruption in the current pregnancy, and 2/6 had a first-degree family history of SPTB. Unfortunately, the small number of non-responders in this subgroup precluded additional regression analyses.

Comment

We have utilized a novel approach to define clinical response to 17OHP-C and have identified several risk factors for non-response to 17OHP-C for the prevention of recurrent SPTB that include the earliest gestational age of previous SPTB(s), vaginal bleeding or abruption in the current pregnancy, and a first-degree family history of SPTB. All of the factors we have identified are known risk factors for SPTB, and given the observational study design, we unable to conclude causality between 17OHP-C treatment and these risk factors.

Vaginal bleeding was one factor we identified as being associated with non-response to 17OHP-C. Prior research has identified decidual hemorrhage, which broadly defined includes both subchorionic hemorrhage and placental abruption as independent risk factors for both SPTB and PPROM.10–12 We also noted a trend towards a greater proportion of non-responders having a history of a placental abruption in a prior pregnancy, but this did not reach statistical significance. These findings together, however, may suggest that women with SPTB and vaginal bleeding or a component of decidual hemorrhage may be less likely to benefit from 17OHP-C compared to women with other SPTB phenotypes.

Our finding that women with a first degree family history of SPTB were more likely to be non-responders may suggest that some women may have ‘inherited’ SPTB that may be less responsive to 17OHP-C. Genetic factors may influence gestational age at delivery in these individuals, but this determination is outside of the scope of the current study. However, all women with a previous SPTB should be queried about the obstetric histories of their first-degree female relatives.

We noted trends towards increased tocolytic use, and specifically, greater use of nifedipine, among 17OHP-C non-responders. We speculate that since non-responders (by definition) were more likely to deliver preterm, they were also more likely to receive treatment to attempt to delay delivery. Although an interaction between 17OHP-C and nifeipine cannot be excluded, it appears unlikely, but cannot be addressed by the current study design.

Our definition of a 17OHP-C responder is innovative and clinically relevant. For example, a woman delivering her first pregnancy at 24 weeks, treated with 17OHP-C in her second pregnancy, and delivering at 32 weeks would have been regarded as having a recurrent preterm birth and a treatment failure using the traditional definition of 17OHP-C response. However, the woman and fetus in this example have gained significant gestational time with 17OHP-C, and small improvements in gestational age (particularly at the earliest gestational ages) translate to substantial decreases in neonatal morbidity and mortality and healthcare costs.13–15 We chose 3 weeks as a ‘cutoff’ to redefine 17OHP-C response in order to increase the generalizability of this definition. The majority of women suffering a SPTB will, either by standard obstetric gestational age criteria or by neonatal physical examination criteria, know within a narrow range the gestational age(s) of their previous SPTB(s). Thus, this reduces the likelihood that a woman would be a 17OHP-C responder or non-responder due to a pregnancy dating error or gestational age recall error. Further, Bloom, et al reported that 70% of women (prior to the era of widespread 17OHP-C use) with a recurrent PTB will deliver within 2 weeks of the delivery gestational age of their first preterm birth, so the majority of women destined to have a recurrent PTB would be considered a non-responder by our definition.16 Importantly, our results were consistent when we limited the cohort to those women at highest risk for recurrent PTB, those with a penultimate PTB. Lastly, results were also consistent regardless of whether the gestational age of the penultimate pregnancy or the gestational age of the earliest prior PTB was used to calculate the 17OHP-C effect and assign 17OHP-C responder status.

Previous investigators have examined the influence of a variety of factors on 17OHP-C response, but in contrast to our study, have analyzed the data used a fixed outcome of ‘term’ delivery to define progesterone response. Two separate retrospective cohort studies have found – paradoxically – that those with a prior PTB due to PPROM (historically at highest risk for recurrent PTB) had lower rates of recurrent prematurity when treated with 17OHP-C compared to those women receiving prophylaxis due to a history of idiopathic preterm labor. In this cohort, we had a small number of women (18, 11.6%) with a history of PPROM, and were unable to confirm this association.17,18 Spong et al, in a secondary analysis of data from the original NICHD randomized controlled trial of 17OHP-C, examined the impact of the gestational age of the prior PTB on the success of 17OHP-C, and found that women with the earliest prior PTB were most likely to deliver at term with 17OHP-C.19 Our findings, despite using a different definition of 17OHP-C treatment ‘success,’ were consistent with those of Spong, et al.

This study should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. Because this was an observational cohort, we were unable to directly compare factors associated with prolongation of pregnancy for a minimum of 3 weeks between individuals who did and did not receive 17OHP-C. Although some portion of women in the original cohort did not receive 17OHP-C, they differed significantly on key demographic and clinical variables from those women who did receive 17OHP-C, precluding a direct comparison. Cervical length screening data were available for only 61% of individuals, limiting our conclusions regarding the relationship between 17OHP-C response and short cervix due to small numbers. Additionally, due to the inclusion criteria of the original study, we were unable to assess the effectiveness of 17OHP-C in the setting of a prophylactic cerclage. Some factors, including family history, are subject to, and limited by, recall bias. Unfortunately, we do not have data regarding the gestational age at initiation of 17OHP-C treatment, the number of doses of 17OHP-C, or 17OHP-C compliance. Prior studies have reported a reduced incidence of SPTB among women initiating 17OHP-C early and an increased incidence of SPTB among women with early cessation of 17OHP-C; unfortunately we were unable to address these issues in the current analysis.20,21 However, all participants were compliant with study visits as described in the methods, and 17OHP-C use is likely to reflect ‘real world’ use. Lastly, we had insufficient numbers to evaluate those delivering significantly earlier with 17OHP-C (a ‘potential harm’ group) as a subgroup.

Our study had several strengths. This was a large, multicenter cohort, with demographic characteristics reflective of the ‘at-risk’ gravida in the United States. This population represented a group at very high risk for SPTB, with the majority experiencing a SPTB in the penultimate pregnancy. SPTB was strictly defined prior to patient enrollment. The prospective study design which incorporated data collection serially throughout pregnancy and standardized data collection reduce the likelihood of recall bias, particularly important for factors such as vaginal bleeding. These data provide important information for the clinician, who may stratify the risk of individuals treated with 17OHP-C, and counsel them accordingly.

In conclusion, several historical and current pregnancy characteristics define women at risk for suboptimal response to 17OHP-C, used for the prevention of recurrent SPTB. These data should be prospectively studied in larger cohorts, and when combined with genetic and environmental data may serve to identify individuals who are candidates for intervention trials of alternative therapies to prevent recurrent SPTB.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences provided grant support for the NICHD Genomics and Proteomics Network for Preterm Birth (GPN). While NICHD staff had input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent the views of the NICHD.

Data collected at participating sites of the GPN were transmitted to Yale University, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the GPN, Dr. Heping Zhang (DCC Principal Investigator) had full access to the clinical data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

Steering Committee Chair: Yoel Sadovsky, MD, Magee-Womens Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development – Uma M. Reddy, MD MPH; John V. Ilekis, PhD; Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System (U01 HD50094, UL1 TR165) – Rachel L. Copper, MSN CRNP; Pamela B. Files, MSN CRNP; Stacy L. Harris, BSN RN.

University of Pennsylvania (U01 HD5088) – Don A. Baldwin, PhD; Rita Leite, MD.

University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (U01 HD50078) – Margaret L. Zimmerle, BSN; Janet L. Brandon, RN MSN; Sonia Jordan, RN BSN; Angela Jones, RN BSN.

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, McKay-Dee Hospital, and Utah Valley Regional Medical Center (U01 HD50080) – Kelly Vorwaller, RN BSN; Sharon Quinn, RN; Valerie S. Morby, RN CCRP; Kathleen N. Jolley, RN BSN; Julie A. Postma, RN BSN CCRP.

Yale University School of Public Health, Collaborative Center for Statistics in Science (U01 HD50062) – Kei-Hoi Cheung, PhD; Donna Losi DelBasso; Buqu Hu, MS; Hao Huang, MD MPH; Lina Jin, PhD; Analisa L. Lin, MPH; Charles C. Lu, MS; Lauren Perley, MA; Laura Jeanne Simone, BA; Chi Song, PhD; Feifei Xiao, PhD; Yaji Xu, PhD.

Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island – Dwight J. Rouse, MD MSPH; Donna Allard, RNC.

Columbia University Hospital, Drexel University, Christiana Care Health Systems, and St. Peter’s University Hospital – Ronald Wapner, MD; Michelle Divito, RN MSN; Sabine Bousleiman, RN MSN MsPH; Vilmarie Carmona, MA; Rosely Alcon, RN BSN; Katty Saravia, MA; Luiza Kalemi, MA; Mary Talucci, RN MSN; Lauren Plante, MD MPH; Zandra Reid, RN BSN; Cheryl Tocci, RN BSN; Marge Sherwood; Matthew Hoffman, MD; Stephanie Lynch, RN; Angela Bayless, RN; Jenny Benson, RN; Jennifer Mann, RN; Tina Grossman, RN; Stephanie Lort, RN; Ashley Vanneman; Elisha Lockhart; Carrie Kitto; Edwin Guzman, MD; Marian Lake, RN; Shoan Davis; Michele Falk; Clara Perez, RN.

Northwestern University – Alan M Peaceman MD, Lara Stein RN, Katura Arego, Mercedes Ramos-Brinson B.S., Gail Mallett RN BSN.

University of North Carolina – John M. Thorp, Jr, MD MPH; Karen Dorman, RN MS; Seth Brody, MD MPH.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District – Sean C. Blackwell, MD; Maria Hutchinson, MPH.

GPN Advisory Board – Anthony Gregg (chair), MD, University of South Carolina School of Medicine; Reverend Phillip Cato, PhD; Traci Clemons, PhD, The EMMES Corporation; Alessandro Ghidini, MD, Inova Alexandria Hospital; Emmet Hirsch, MD, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; Jeff Murray, MD, University of Iowa; Emanuel Petricoin, PhD, George Mason University; Caroline Signore, MD MPH, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Charles F. Sing, PhD, University of Michigan; Xiaobin Wang, MD, Children Memorial Hospital.

Funding: This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Genomic and Proteomic Network for Preterm Birth Research (U01-HD-050062; U01-HD-050078; U01-HD-050080; U01-HD-050088; U01-HD-050094), all authors. This study was also funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development 5K23HD067224 (Dr. Manuck).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement: Dr. Sean Esplin serves on the scientific advisory board and holds stock in Sera Prognostics, a private company that was established to create a commercial test to predict preterm birth and other obstetric complications. Dr. Tracy Manuck is also on the scientific advisory board for Sera Prognostics. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Presentation: This study was presented in part at the 35th Annual Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine Meeting (February 2015, San Diego, CA) as a poster presentation (final abstract ID # 560).

References

- 1.Schoen CN, Tabbah S, Iams JD, Caughey AB, Berghella V. Why the United States preterm birth rate is declining. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson JJ, McWilliam OA, Newnham JP, Pennell CE. Preterm birth aetiology 2004–2008. Maternal factors associated with three phenotypes: spontaneous preterm labour, preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes and medically indicated preterm birth. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2012;25:642–7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.597899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MM, Elam-Evans LD, Wilson HG, Gilbertz DA. Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2000;283:1591–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esplin MS, O’Brien E, Fraser A, et al. Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:516–23. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184181a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonsen SE, Lyon JL, Stanford JB, Porucznik CA, Esplin MS, Varner MW. Risk factors for recurrent preterm birth in multiparous Utah women: a historical cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:863–72. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManemy J, Cooke E, Amon E, Leet T. Recurrence risk for preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:576 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.039. discussion e6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:2379–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manuck TA, Watkins WS, Moore B, et al. Pharmacogenomics of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for recurrent preterm birth prevention. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;210:321 e1–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manuck TA, Lai Y, Meis PJ, et al. Progesterone receptor polymorphisms and clinical response to 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;205:135 e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramaeker DM, Simhan HN. Sonographic cervical length, vaginal bleeding, and the risk of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:224 e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson JA, Odibo AO, Shanks AL, Roehl KA, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Adverse outcomes in twin pregnancies complicated by early vaginal bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:56 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lykke JA, Dideriksen KL, Lidegaard O, Langhoff-Roos J. First-trimester vaginal bleeding and complications later in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:935–44. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da8d38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity–moving beyond gestational age. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:1672–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikkola K, Ritari N, Tommiska V, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age of a national cohort of extremely low birth weight infants who were born in 1996–1997. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1391–400. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phibbs CS, Schmitt SK. Estimates of the cost and length of stay changes that can be attributed to one-week increases in gestational age for premature infants. Early human development. 2006;82:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloom SL, Yost NP, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Recurrence of preterm birth in singleton and twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:379–85. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Cordova YC, Istwan NB, et al. Influence of gestational age and reason for prior preterm birth on rates of recurrent preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:275 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman S, Wallace L, Alexander J, Istwan N. Recurrent preterm birth in women treated with 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate: the contribution of risk factors in the penultimate pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:1034–8. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.614657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spong CY, Meis PJ, Thom EA, et al. Progesterone for prevention of recurrent preterm birth: impact of gestational age at previous delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rebarber A, Ferrara LA, Hanley ML, et al. Increased recurrence of preterm delivery with early cessation of 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196:224 e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markham KB, Walker H, Lynch CD, Iams JD. Preterm birth rates in a prematurity prevention clinic after adoption of progestin prophylaxis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;123:34–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]