Abstract

Lysine-specific demethylase 1A (KDM1A/LSD1) is a FAD-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative demethylation of histone H3K4me1/2 and H3K9me1/2 repressing and activating transcription, respectively. Although the active site is expanded compared to that of members of the greater amine oxidase superfamily, it is too sterically restricted to encompass the minimal 21-mer peptide substrate footprint. The remainder of the substrate/product is therefore expected to extend along the surface of KDM1A. We show that full-length histone H3, which lacks any posttranslational modifications, is a tight-binding, competitive inhibitor of KDM1A demethylation activity with a Ki of 18.9 ± 1.2 nM, a value that is approximately 100-fold higher than that of the 21-mer peptide product. The relative H3 affinity is independent of preincubation time, suggesting that H3 rapidly reaches equilibrium with KDM1A. Jump dilution experiments confirmed the increased binding affinity of full-length H3 was at least partially due to a slow off rate (koff) of 1.2 × 10−3 s−1, corresponding to a half-life (t1/2) of 9.63 min, and a residence time (τ) of 13.9 min. Independent affinity capture surface plasmon resonance experiments confirmed the tight-binding nature of the H3/KDM1A interaction, revealing a Kd of 9.02 ± 2.3 nM, a kon of (9.3 ± 1.5) × 104 M−1 s−1, and a koff of (8.4 ± 0.3) × 10−4 s−1. Additionally, no other core histones exhibited inhibition of KDM1A demethylation activity, which is consistent with H3 being the preferred histone substrate of KDM1A versus H2A, H2B, and H4. Together, these data suggest that KDM1A likely contains a histone H3 secondary specificity element on the enzyme surface that contributes significantly to its recognition of substrates and products.

Chromatin condensation and relaxation and the dynamic control of gene expression are regulated by posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of histone proteins by epigenetic enzyme complexes.1,2 Dysregulation of histone-modifying enzymes within these complexes underscores several disease pathologies, including cancers.3 As such, this class of enzymes has become the subject of intense inquiry for their potential role as targets for therapeutic intervention. Among these PTMs is histone lysine methylation, a mark that is intimately linked to both transcriptional activation and repression.4

Although evidence of enzymatic demethylation of histones would arise with the work of Paik and Kim in 1973,5 it would not be until almost four decades later that an enzyme directly responsible for this activity would be uncovered. The isolation and characterization of lysine-specific demethylase 1A (KDM1A, also known as LSD1/AOF2/BHC110/KIAA0601/p110b) by Shi and co-workers provided direct evidence that histone lysine methylation was, in fact, a reversible mark.6 KDM1A is a flavin-dependent amine oxidase that catalyzes the removal of methyl groups of mono- and dimethylated lysine residues at positions 4 and 9 on histone H3 (H3K4me1/2 and H3K9me1/2, respectively).6–8 From N- to C-terminus, KDM1A is composed of an unstructured region that contains the nuclear localization signal9,10 and three structured domains: a SWI3p, Rsc8p, and Moira (SWIRM) domain, an amine oxidase domain (AOD), and an unprecedented intervening domain within the AOD colloquially known as the tower (Figure 1A).11,12

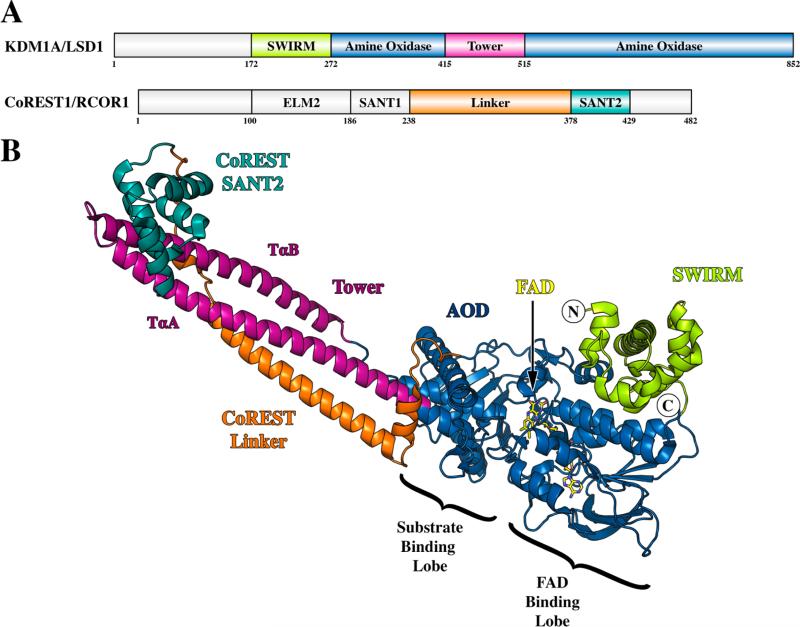

Figure 1.

Domain and structural overview of KDM1A and CoREST. (A) Domain maps of KDM1A and CoREST1. For KDM1A, the SWIRM domain is colored green, the AOD blue, and the tower domain magenta. For CoREST, the linker is colored orange and SANT2 cyan. The ELM1 and SANT1 domains are colored gray because of the lack structural information. (B) Structural overview of KDM1A in complex with CoREST-C (residues 286–482). The coloring scheme follows that of the domain maps above; FAD is colored yellow, and N- and C-termini are labeled (PDB entry 2IW5).

More specifically, the tower domain of KDM1A is composed of two antiparallel α-helices (termed TαA and TαB) that form a coiled coil and extend approximately 100 Å from the AOD (Figure 1B).11,12 Functionally, this domain is the site of association with the corepressor of the RE1-silencing transcription factor (CoREST, also known as CoREST1/RCOR1/KIAA0071) as well as several homologous proteins (Figure 1B).12–15 Interestingly, CoREST endows KDM1A with the ability to demethylate nucleosomal substrates as a noncatalytic domain donor with DNA binding ability bridging the gap between KDM1A and its substrates.15–19 On the other hand, the SWIRM domain of KDM1A, which is found in multiple chromatin-associated proteins,20 is a bundle of α-helices with a central helix that is joined by two smaller helix–turn–helix motifs (Figure 1B).11 Moreover, consistent with other flavin-dependent oxidoreductases, the AOD of KDM1A houses a noncovalently bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor and can be further subdivided into an expanded Rossman fold for cofactor binding and the substrate-binding lobe (Figure 1B).12,15 Although these characteristics group KDM1A into the larger family of flavoenzymes, the structure of the AOD does contain unique features because of the functional activity of the enzyme.

As compared to other amine oxidases, KDM1A contains a more expansive substrate-binding cavity (~1245 Å3) that is suggested to complement its broad substrate specificity, including non-histone proteins.12,21 Additionally, although KDM1A requires a peptide substrate of at least 21 residues representing the N-terminal portion of histone H3 for efficient catalysis,22 the active site cavity is too sterically restricted to accommodate this entire fragment.12 In efforts to decode substrate specificity, several groups have cocrystallized peptides with KDM1A that revealed two main conformations.23–25 Interestingly, the conformations result in the C-terminus of the peptide exiting the active site in different orientations. Further confounding these results, Luka and co-workers recently determined a structure of KDM1A in complex with tetrahydrofolate and suggested that the cofactor may sterically disrupt one of the observed binding conformations.26 Prior to this finding, several groups have suggested that KDM1A substrates exit the active site and extend along a conspicuous surface groove along the SWIRM/AOD interface aiding in substrate binding and recognition.11,15,27,28

Consistent with this hypothesis, mutations to residues that lie within this groove greatly reduce or abrogate the catalytic efficiency of KDM1A.11 Additionally, Tochio and co-workers demonstrated via surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies that an isolated SWIRM domain of KDM1A is able to bind the N-terminal tail of histone H3.29 Confounding these results, however, a 30-mer H3 peptide substrate showed no apparent change in catalytic efficiency when compared to that of a 21-mer.22 Additionally, none of the structural studies listed above revealed electron density in the cleft along the SWIRM/AOD interface, raising the question of whether this phenomenon exists and if so where the secondary binding site resides.

Herein, we describe the kinetic analysis of full-length histone products against KDM1A as a preliminary investigation to determine whether the enzyme recognizes additional residues of these species as compared to truncated peptide analogues. We now show by several different experimental approaches that histone H3 is a tight-binding, competitive inhibitor of KDM1A demethylation activity and has an affinity 100-fold higher than that of the 21-mer peptide product. We suggest that the potency of H3 inhibition is at least partially due to the slow off rate of the full-length product, as jump dilution experiments reveal a discernible half-life of the H3/KDM1A binary complex. As suspected, no other histone proteins inhibit KDM1A demethylation activity. Together, these results suggest that KDM1A contains a secondary histone H3-binding site on the enzyme surface that adds a perceived level of complexity to KDM1A product and substrate interactions. Additionally, our work further validates the suggested role of KDM1A as a contributor to the stabilization of associated multiprotein complexes within genetic loci.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Materials

The clone of Homo sapiens protein KDM1A (UniProtKB accession no. O60341; residues 151–852) was codon optimized for expression in Escherichia coli and synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The pDB-HisGST expression vector was obtained from the DNASU Plasmid Repository. Buffer salts were obtained from Sigma, EMD Millipore, and J. T. Baker. trans-2-Phenylcyclopropylamine hydrochloride salt (2-PCPA), 4-AAP, and 3,5-DCHBS were obtained from Sigma. Protein purification was conducted using an ÄKTA FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences).

Expression and Purification of nΔ150 KDM1A

The gene encoding nΔ150 KDM1A was subcloned into a pET-15b vector (Novagen) containing an N-terminal six-His tag with an intervening thrombin cleavage site, utilizing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The clone was expressed and purified as previously reported with minor modifications (see the Supporting Information for a detailed procedure).13,30 The final concentration of KDM1A was routinely determined by UV absorption spectroscopy using an extinction coefficient of 10790 M−1 cm−1 at 458 nm, which was determined after protein denaturation using 0.3% (w/v) SDS.22,31

Expression and Purification of His-GST-CoREST-C

The gene encoding CoREST-C (CoREST1/RCOR1; UniProtKB accession no. Q9UKL0; residues 286–482) from H. sapiens was subcloned into a pDB-HisGST expression vector, containing an N-terminal six-His tag and GST tag with an intervening tobacco etch virus protease (TEV) cleavage site, utilizing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The clone was expressed and purified as previously reported with minor modifications.32 Following IMAC, fractions containing His-GST-CoREST-C were extensively dialyzed against GST-PBS dialysis buffer [137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), and 5 mM βME] overnight in 3.5 kDa MWCO SnakeSkin dialysis tubing (Thermo Scientific) and applied at a rate of 0.1 mL/min to 10 mL of Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare). The column was washed at a rate of 2.0 mL/min with 5 column volumes (CV) of GST-PBS dialysis buffer followed by 10 CV of TEV cleavage buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)]. GST tag cleavage was performed by incubating column-bound protein in a 0.1:1 ratio of seven-His TEV (S219V), prepared by previously described methods,33 to column bound protein overnight. Eluted CoREST-C was pooled and supplemented with 5 mM imidazole and passed over IMAC resin equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole to remove TEV protease. Samples containing CoREST-C were pooled and concentrated using 5 kDa MWCO Vivaspin 20 centrifugal filters at 2000g. Samples were aliquoted, flash-frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C. This method routinely provides protein at >90% purity as assessed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and with typical yields of 1.5 mg/L of culture as determined by the Bradford method.

Expression and Purification of His-GST-CoREST-Linker

The coding sequence of the linker region of CoREST (residues 293–380) was extracted and amplified by using polymerase chain reaction with a forward primer (5′-GCGCATATGGTCAAAAAAGAAAAACATAGC-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GCGCTCGAGTTAATTACATTTCTGAATGACC-3′) under the following conditions: an initial denaturation step for 2 min at 95 °C, 30 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 95 °C, annealing for 30 s over a gradient from 54 to 65 °C, elongation for 1 min at 72 °C, and a final elongation step for 10 min at 72 °C. The primers were designed to contain NdeI and XhoI restriction sites at the N- and C-termini, respectively, to allow for facile ligation into the pDB-HisGST expression vector. The resulting His-GST-CoREST-Linker construct was expressed and purified as described above for His-GST-CoREST-C.

Purification of KDM1A/CoREST Complexes

Purified CoREST constructs were mixed with KDM1A in a 1.5:1 molar ratio and allowed to incubate for 1 h on ice. Incubated samples were then purified using a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with 25 mM HEPES-Na (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM βME and eluted at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. The elution peaks had retention volumes that corresponded to the molecular weight of the complexes. Formation was further verified by SDS–PAGE. Complexes were stored at −20 °C in gel filtration buffer with a final concentration of 40% glycerol.

Expression and Purification of Histone Proteins

Expression and purification of core histone proteins were conducted by combining two previously reported methods with minor modifications (see the Supporting Information for a detailed procedure).34,35 The concentration of the histone proteins was determined by the Bradford method incorporating a standard curve slope correction factor that took into account the relative content of His, Arg, and Lys residues versus the BSA standard.36 Additionally, protein concentration and standard curves were determined by analysis of the ratio of absorbance at 595 and 466 nm.37

Synthesis and Purification of Histone H3 Substrate and Product Peptides

A peptide corresponding to the first 21 amino acids of the N-terminal tail of histone H3 that incorporated a dimethylated lysine at residue 4 (H3K4me21–21) was synthesized and purified as previously described.30,38 The unmodified 21-mer histone H3 product peptide (H31–21) was synthesized and purified in a similar fashion. A C-terminal GYG was added to both the substrate and product peptides to allow for quantification of the peptide concentration at 280 nm, using an extinction coefficient of 1490 M−1 cm−1 for tyrosine.30,38,39

Steady-State Kinetic Assays

Steady-state kinetic assays employing continuous fluorescence or absorbance-based methods for detection of enzymatic peroxide production (Figure S1) were performed as previously described with slight modifications (see the Figures S2 and S3 for details).30,38

KDM1A tolerance for 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was assessed to confirm the usable range of additives (Figure S4). DMSO seemingly increases the initial velocity of KDM1A within 2-fold under 10% (v/v) DMSO. The CHAPS concentration for disruption of nonspecific aggregation effects was kept at 0.01% (w/v) in inhibitor analyses. For all IC50 titrations, unless otherwise noted, the substrate concentration was held at or near the apparent Km (Kmapp) to ensure an equal population of the free enzyme and ES complex was available for inhibitor interactions.40,41

Steady-State Kinetic Data Analysis

Steady-state kinetic data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) or Grafit 4.0 (Erithacus Software, London, U.K.). Briefly, the no enzyme control (n = 3) was subtracted from all data sets. Data were then forced through the origin by subtraction of the initial time point and responses converted to concentration units of H2O2 (micromolar). Initial velocities were calculated via linear regression, and responses were limited to within 10% total product conversion. Initial velocities were then plotted versus substrate concentrations and fit to the Henri–Michaelis–Menten equation (eq 1)42 utilizing nonlinear regression analysis:

| (1) |

where v0 is the experimental initial velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vmax is the maximal velocity at the utilized enzyme concentration, and Km is the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity.

Dose–response curves were prepared by comparing initial rate data at specified inhibitor concentrations to a no inhibitor control and fit directly to eq 2:

| (2) |

where v0 is the initial velocity of the control, vi is the inhibited initial velocity, [I] is the inhibitor concentration, IC50 is the inhibitor concentration at which the rate of demethylation is half that of the control, and h is the Hill coefficient of the curve (slope factor).

The Ki of reversible, competitive inhibitors was determined by a titration of inhibitor versus substrate followed by global fitting of the data to eq 3:

| (3) |

where Ki is the equilibrium inhibitory constant.

As a secondary determination of Ki, we used the Cheng–Prusoff relationship for competitive inhibition:43

| (4) |

where IC50 is the inhibitor concentration at which the rate of demethylation is half that of the control as defined above in eq 2.

To define the apparent Ki (Kiapp) value of inhibitors that fall in the tight-binding regime (i.e., ≤10[E]T), dose–response data were fit to Morrison's quadratic equation for tight-binding inhibition:44

| (5) |

where [I]T is the total inhibitor concentration, Kiapp is the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant for the enzyme/inhibitor complex, and [E]T is the total enzyme concentration.

As a secondary determination of Kiapp, data were transformed for analysis via a Henderson plot45 and fit to the following linear expression:

| (6) |

The IC50 dependence on enzyme concentration for confirmation of the tight-binding nature of the inhibitor and as an additional means to determine Kiapp was fit to the following equation:

| (7) |

where m is the linear slope.

To determine the equilibrium inhibitory constant (Ki) of tight-binding competitive inhibitors, data were fit to the following equation:

| (8) |

Determination of Rates of Dissociation of H3 from KDM1A

Rates of dissociation for the H3/KDM1A binary complex were determined by monitoring the recovery of activity following a 1 h preincubation that included 50Kiapp of histone H3 (3.0 μM) and 100[E] (2.5 μM KDM1A) to ensure saturation of enzyme46 (note that H31–21 and 2-PCPA were incubated at 10IC50 because they do not display tight-binding characteristics, 50 and 200 μM, respectively). Preincubated samples were diluted 100-fold into assay buffer containing 5Km of H3K4me21–21 peptide substrate (25 μM), 50 μM Amplex Red, and 1 unit/mL HRP. Product was monitored continuously using an absorbance maximum at 572 nm for resorufin. Progress curve data were fit to eq 9 to generate kobs:

| (9) |

where vi and vs represent the initial and steady-state velocities, respectively, kobs is the apparent first-order rate constant for the transition from vi to vs, and t is time. Under the experimental conditions used, kobs approximates the dissociation rate constant (koff) of the enzyme/inhibitor complex. The enzyme/inhibitor dissociation half-life (t1/2) was calculated using the formula t1/2 = 0.693/koff, and the residence time (τ) was calculated using the equation τ = 1/koff.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Measurements

All SPR measurements were taken using a BIAcore 3000 instrument, and data analyses were performed using BIAevaluation version 4.1 (BIAcore). An anti-histone H3 antibody (Abcam, ab1791) was immobilized [<3000 response units (RU)] on a research grade BIAcore CM5 chip using EDC-sNHS coupling chemistry with reagents obtained from BIAcore according to the manufacturer's protocol. In a parallel flow cell, an anti-lysozyme antibody (Abcam, ab2408) was immobilized (<2800 RU). During the screening experiments with degassed 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) and 1 mM DTT as a running buffer, H3 and lysozyme were injected over immobilized antibodies in respective flow cells for 2 min at a flow rate of 30 μL/min and washed with running buffer until sensograms equilibrated. KDM1A was then injected for 2 min at a flow rate of 30 μL/min to monitor the binding interaction. The surfaces were regenerated via injection of 10 μL of glycine (pH 2.0) at a flow rate of 50 μL/min. The response from the KDM1A/lysozyme/anti-lysozyme antibody surface was used to subtract out the background (nonspecific) signal. The Kd value of the H3/KDM1A interaction was measured via injection of KDM1A for 2 min at various concentrations ranging from 5.0 to 50.0 nM. Global curve fitting to the 1:1 Langmuir binding model was used to determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates and the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd).

RESULTS

CoREST (CoREST1/RCOR1) Does Not Alter the Catalytic Efficiency of KDM1A toward Minimal Peptide Substrates

KDM1A requires a minimal substrate corresponding to the first 21 residues of the N-terminal histone H3 tail for efficient demethylation activity.22 Although the enzyme itself is sufficient for demethylation of peptide and histone substrates, activity toward nucleosomes in vitro is regulated by its interaction with CoREST, the minimal portion of which contains the linker and SANT2 domain or possibly the SANT1 domain.15,16,18 As such, we wanted to evaluate KDM1A activity toward a peptide substrate in the presence and absence of various CoREST constructs to determine the degree to which the partner influenced its catalytic activity and/or affinity for its substrates. Kinetic parameters and representative data for KDM1A activity in the presence of equimolar CoREST are listed in Table 1. Of the complexes tested, KDM1A/CoREST-Linker (residues 293–380) and KDM1A/CoREST-C (residues 286–452) showed only a very modest 1.5-fold increase in the initial velocity as compared to that of KDM1A. Despite this enhanced velocity, the complexes maintained nearly identical catalytic efficiencies because of a proportional increase in the apparent Km. We should note that our derived kinetic values are in reasonable agreement with previously reported values with and without CoREST.13,22,23,30

Table 1.

Representative Steady-State Kinetic Parameters of KDM1A and Differential KDM1A/CoREST Complexes Using an H3K4me21–21 Peptide Substrate

| Kmapp (μM) | kcatapp (min−1) | kcatapp/Kmapp (μM−1 min−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| nΔ150 KDM1Aa | 4.46 ± 0.27 | 6.00 ± 0.07 | 1.35 ± 0.25 |

| nΔ150 KDM1A/CoREST-Linkera | 8.89 ± 0.65 | 9.42 ± 0.10 | 1.06 ± 0.37 |

| nΔ150 KDM1A/CoREST-Ca | 8.14 ± 0.52 | 9.54 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.30 |

In 50 mM HEPES-Na (pH 7.5), 125 μM 4-AAP, 1.0 mM 3,5-DCHBS, 300 nM E, and 1 unit/mL HRP at 25 °C in air-saturated buffer; peptide titrated from 50 μM to 0 in a 2-fold dilution series (n = 3).

H31–21 Is a Competitive Inhibitor of KDM1A Demethylation Activity

To provide a basis for comparison of full-length products, we first reconfirmed the inhibition modality and potency of the peptide products of the enzymatic reaction (Figure S5). The unmodified peptide product representing the first 21 residues of histone H3 (H31–21) has previously been reported to be a competitive inhibitor of KDM1A activity with a Ki of 1.8 ± 0.6 μM.22 To eliminate any potential deleterious nonspecific aggregation effects, we utilized 0.01% (w/v) CHAPS in our assay buffers.47 Dose–response curves of H31–21 showed an average IC50 of 4.84 ± 0.16 μM for KDM1A. The potency and mechanism of inhibition of H31–21 toward KDM1A were determined through a double titration of inhibitor ([I] that gives 30–75% activity as determined by eq 2) versus the substrate followed by global fitting of the data. The data were fit to models of competitive, uncompetitive, and noncompetitive inhibition and were best described by a competitive model, as determined by F-test analysis. The double titration revealed a Ki of 1.77 ± 0.08 μM. Subsequent reciprocal transformation and Lineweaver–Burk plot analysis of the data also fit the pattern to competitive inhibition, resulting in a series of nested lines intersecting at a single y-intercept. Additionally, a secondary plot of apparent Km versus [I] also revealed a Ki of 1.84 ± 0.14 μM, while the Cheng–Prusoff relationship for competitive inhibition yielded a value of 2.07 ± 0.07 μM.43 In our hands, the competitive nature of the product peptide and potency is nearly identical to that previously reported.

The H3/KDM1A Interaction Reaches Rapid Equilibrium

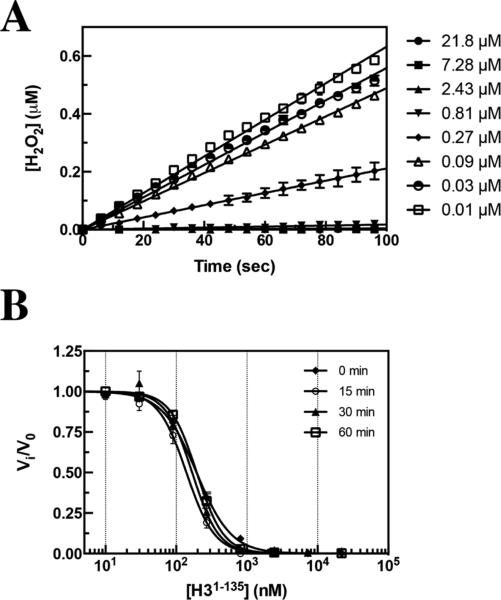

With the relative affinity and competitive nature of the unmodified peptide product reassessed, we looked to investigate the full-length H3 product (H31–135). As an initial test of potency, we assessed the dose–response curve of H3 inhibition of KDM1A-mediated demethylation of a peptide substrate. The initial rates as a function of H3 do not appear to be curvilinear in nature and are best fit by linear regression (Figure 2A). This suggests that the degree of inhibition at a fixed concentration of H3 does not vary over time and the interaction is not slow binding in nature. However, in some cases, the establishment of the enzyme–inhibitor equilibrium is much slower than the course of the assay.

Figure 2.

Investigation of the time dependence of inhibition of full-length histone H3 against KDM1A as monitored in a fluorescence-based HRP coupled assay. (A) Linear fit of the initial velocity of KDM1A in the presence of increasing concentrations of histone H3 with no preincubation prior to assay initiation and H3K4me21–21 substrate held at the apparent Km. (B) Investigation of IC50 values with preincubation of KDM1A in the presence of full-length H3 prior to assay initiation into a substrate solution showing no apparent time dependence with an average of 153 ± 26 nM ([E]T = 175 nM).

To assess this potential explanation for the increase in the observed binding affinity, we preincubated KDM1A with H3 for specified times and then initiated the assay. We observed no significant change in IC50 as a function of time even with long preincubation times of up to 1 h. Analysis of the dose–response curves resulted in an average IC50 of 153 ± 26 nM ([E]T = 175 nM) (Figure 2B), a value within the theoretical tight-binding limit of the assay. As there was no change in the average IC50 as a function of time, and the initial velocities as a function of [I] appear to be linear, we suggest that H3 and KDM1A reach rapid equilibrium under the assay parameters utilized. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that the time-dependent transition occurs at a rate that is faster than the detection limits of the assay used.

We should note that as controls we tested the activity of HRP in the presence of increasing concentrations of full-length histone H3. Hydrogen peroxide (2.5 μM) and HRP (1 unit/mL) were set at fixed concentrations and titrated against H3. In this assay, HRP retained all of its activity even at the highest concentrations tested (Figure S6A). Additionally, H3 was tested for its ability to quench resorufin-derived fluorescence and absorbance as well as quinoneimine dye-derived absorbance (Figure S6B,C). In this assay, peroxide was titrated against fixed HRP and H3 to establish standard curves of responses versus peroxide concentration. Even at the highest concentrations of H3 tested, these assays showed no statistical difference between standard curves prepared in the presence and absence of H3. These controls strongly suggest that the inhibitory activity realized in the demethylation assays was solely due to the H3/KDM1A interaction.

Full-Length Histone H3 Is a Tight-Binding, Competitive Inhibitor of KDM1A

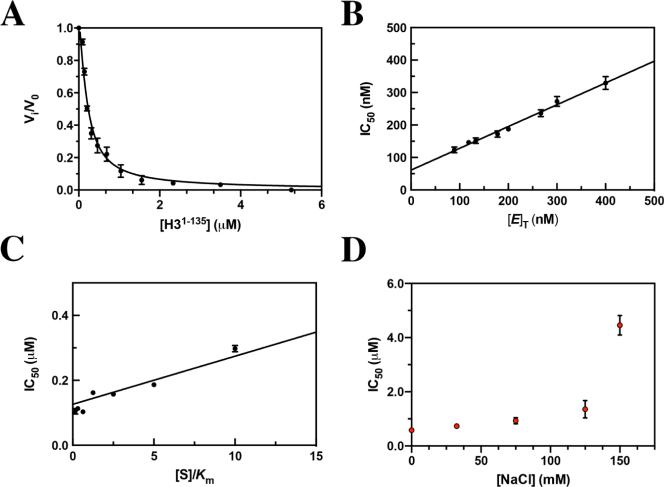

As noted above, the average IC50 of full-length H3 toward KDM1A appears to be within the theoretical tight-binding limit (i.e., ≤10-fold [E]T). Therefore, to assess the apparent affinity of H3 for KDM1A, we first conducted a titration of H3 at a starting point of 30-fold [E]T in a 1.5-fold dilution series.48 Data were fit to the Morrision quadratic equation for concentration–response data for tight-binding inhibitors (eq 5), resulting in a Kiapp of 59.1 ± 6.0 nM (Figure 3A). Data were additionally analyzed via a Henderson plot revealing a Kiapp of 103.4 ± 4.47 nM that was consistent with the tight-binding nature of the H3 interaction (Figure S7).45

Figure 3.

Inhibition profiling of full-length histone H3 against KDM1A as monitored in fluorescence-based HRP-coupled assay reveals the tight-binding nature of the interaction. (A) Concentration–response plot of H3 (1.5-fold dilution series from 30-fold [E]T) against KDM1A fit to Morrison's equation revealing a Kiapp of 59.1 ± 6.0 nM. (B) Plot of IC50 as a function of [E]T measured over a range of KDM1A concentrations from 88.9 to 400 nM generating a Kiapp of 61.2 ± 5.8 nM. (C) A plot of IC50 as a function of [S]/Km over a range of concentrations from 0.156Km to 10.0Km is best fit to a competitive model generating a Ki of 18.9 ± 1.2 nM. (D) A plot of IC50 as a function of NaCl concentration from 0 to 150 mM suggests that the H3/KDM1A interaction is ionic in nature.

One of the hallmarks of tight-binding ligands is the dependence of IC50 on enzyme concentration (eq 7).49 Therefore, to further confirm the tight-binding nature of full-length H3, we assessed the effect of enzyme concentration on IC50. Here, the enzyme at differential concentrations was titrated against histone H3 with a fixed concentration of peptide substrate held at the apparent Km (Figure 3B). Linear regression of the data resulted in a Kiapp of 61.2 ± 5.8 nM. This analysis again confirmed the tight-binding nature of the H3/KDM1A interaction that leads to complications upon assessment of ligand modality.

Because the potency of H3 is near the concentration of KDM1A used in the assays, standard mechanism of inhibition determination through double titration of the inhibitor followed by global fitting of the data is precluded. Instead, the IC50 values determined at several substrate concentrations were plotted against the [S]/Km ratio (0.156Km to 10Km) (Figure 3C). The data were fit to models of competitive, uncompetitive, and noncompetitive inhibition and were best fit by a competitive model as determined by F-test analysis. A Ki of 18.9 ± 1.2 nM was observed. This Ki is a nearly 100-fold increase in binding affinity toward the free enzyme as compared to that of the peptide product described above.

To determine if the binding affinity of H31–135 was primarily either electrostatic or hydrophobic in nature, an IC50 shift assay was completed with increasing NaCl concentrations. At higher ionic strengths, the potency of H31–135 toward KDM1A in the demethylation assay decreased (Figure 3D). On the basis of these data, we suggest that the interaction of H31–135 with KDM1A is likely to be mostly electrostatic in nature. It is interesting to note that KDM1A showed negligible activity over background at 300 mM NaCl (data not shown). Therefore, as a control experiment, we repeated the titration of H31–135 against HRP in the presence of H2O2 and 300 mM NaCl, and activity was unaffected (data not shown). We can therefore conclude that the binding of KDM1A to the peptide substrate H3K4me1/21–21 is also electrostatic in nature, which was also postulated by Forneris and co-workers.22

The Histone H3/KDM1A Binary Complex Has an Observable Residence Time

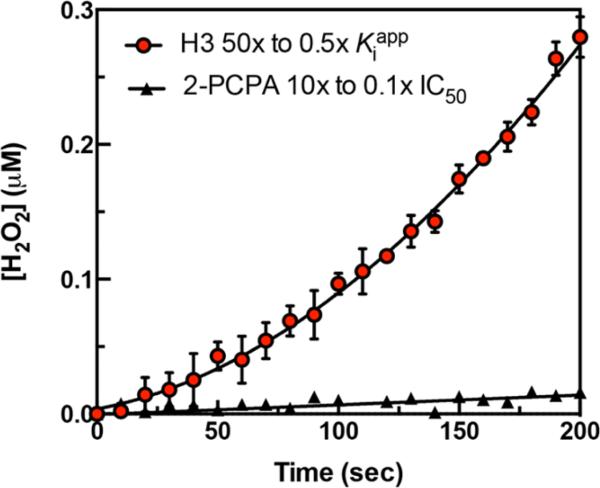

To confirm the reversibility of inhibition and to determine the off rate (koff) of full-length H3 binding, rapid dilution experiments in which the enzyme and inhibitor were preincubated for 1 h were conducted. The enzyme/inhibitor complex was then diluted 100-fold into assay buffer containing the peptide substrate, coupling enzyme, and chromophore. Reaction progress curve data show that KDM1A activity slowly recovers over time (t1/2 = 9.63 min) (Figure 4). In control experiments using the H3 product peptide (H31–21), the progress curve appears to be linear, as there is no distinguishable delay in the recovery of activity (Figure S8). Additionally, t1/2 could not be defined by the data, suggesting that this interaction is rapidly reversible (Table 2). We also used 2-PCPA as a mechanism-based irreversible inhibitor control,38 in the presence of which KDM1A did not recover activity as expected (Figure 4). The jump dilution experiment confirms the long residence time and reversibility of the H3/KDM1A interaction.

Figure 4.

H3/KDM1A binary complex with an observable residence time. KDM1A (2.5 μM) and H3 (3.0 μM, 50Kiapp) or 2-PCPA (200 μM, 10IC50) were incubated for 1 h followed by 100-fold dilution into assay buffer containing 25 μM peptide substrate, 50 μM Amplex Red, and 1 unit/mL HRP. The recovery of enzyme activity was monitored over time by monitoring the resorufin-derived absorbance at 572 nm. Histone H3's inhibition of KDM1A is slowly reversible with an off rate of 1.2 × 10−3 s−1 as compared to that of 2-PCPA, for which the activity was not recovered.

Table 2.

Inhibition Constants for Full-Length Histones and Histone Peptides against KDM1Aa

| entry | IC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | koff (s−1) | residence time (τ) (min) | half-life (t1/2) (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H31–21 | 4840 | 1770 | ND | ND | ND |

| H3 | 153 | 18.9 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 13.9 | 9.63 |

| H4 | N/A | – | – | – | – |

| H2A | N/A | – | – | – | – |

| H2B | N/A | – | – | – | – |

N/A means not applicable; therefore, entry did not effectively inhibit KDM1A. IC50 values were determined at 5.0 μM(~Kmapp) KDM1A and 175 nM KDM1A. ND means not determined; therefore, inhibition was rapidly reversible. Residence time was calculated with the formula τ = 1/koff, assuming that the dilution is large enough that the rate of compound rebinding is assumed to be insignificant. Half-life was calculated with the formula t1/2 = 0.693/koff.

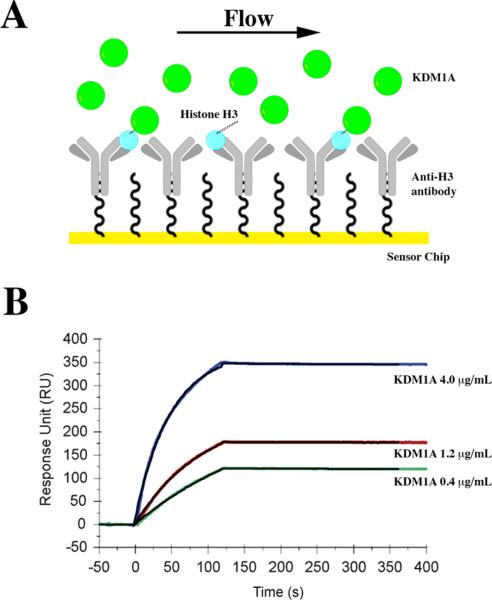

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Measurements

To confirm the tight-binding interaction between KDM1A and full-length H3 independent of catalysis, we turned to SPR measurements. Here, an antibody specific to the C-terminus of histone H3 was covalently immobilized on the chip surface as the capturing antibody to which H3 was immobilized. This experimental setup allowed subsequent analysis of the H3/KDM1A binding interaction (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, the increase in response units over time represents the amount of KDM1A bound to the antibody-immobilized histone H3. This response is proportional to the association rate constant (kon) of (9.3 ± 1.5) × 104 M–1 s–1. After the association of KDM1A and immobilized H3, additional buffer was injected over the flow cell to dissociate the bound enzyme. This analysis yielded a dissociation rate constant (koff) of (8.4 ± 0.3) × 10–4 s–1. These calculated rate constants result in an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 9.02 ± 2.3 nM that is within approximately 2-fold of that calculated in the continuous assay. This technique independently confirmed that the interaction between KDM1A and H3 has a Kd in the low nanomolar, tight-binding range and is suggestive of a 1:1 stoichiometry. Additionally, the off rate determined from this experiment is in good agreement with the results of the rapid dilution experiment. We also suggest that the presence of DTT in the running buffers strongly precludes the formation of disulfide bonds as a contributing factor of the tight-binding nature of the H3/KDM1A interaction.

Figure 5.

Surface plasmon resonance experiments independently confirm the tight-binding nature of the H3/KDM1A interaction. (A) Diagram of the experimental setup in which the anti-H3 antibody was covalently immobilized to the chip surface to capture histone H3. KDM1A was subsequently injected over the chip surface to monitor binding. (B) Response curves obtained during and after injection of KDM1A over the antibody-immobilized H3 chip surface. Global curve fitting of sensograms reveals an association rate constant (kon) of (9.3 ± 0.3) × 104 M–1 s–1 and a dissociation rate constant (koff) of (8.4 ± 0.3) × 10−4 s−1 that were used to calculate a dissociation constant (Kd) of 9.02 ± 2.3 nM.

Additional Core Histone Proteins Have No Effect on KDM1A

Several groups have illustrated that KDM1A catalyzes the oxidative demethylation of histone H3K4me1/2 and H3K9me1/2 as well as non-histone substrates.6–8,21 Despite a broad substrate specificity profile, the demethylase has never been reported to recognize PTMs on the additional core histone proteins. To confirm this observation in terms of inhibition of demethylation activity, dose–response titrations were completed for each of the other core histone proteins, H2A, H2B, and H4, against KDM1A. Consistent with these reports, none of the other core histone proteins inhibited KDM1A activity (Figure S9). We can safely conclude that the demethylase specifically recognizes histone H3 and is not negatively regulated by the other core histones. However, this analysis does not prove or disprove that KDM1A may contain surface recognition elements that bind these other core histones.

DISCUSSION

Many groups have suggested that the substrates and products of KDM1A exit the expanded yet restricted active site pocket and interact with a secondary binding site on the enzyme surface.11,15,27,28 This secondary surface element is expected to facilitate substrate/product binding and recognition. To assess this hypothesis, we investigated the ability of unmodified, full-length histone proteins to inhibit KDM1A-dependent demethylation activity. We chose longer, “native-like” products to determine whether the enzyme could potentially recognize a larger portion of these species, thereby increasing the apparent binding affinity.

Before we began this study, we chose to assess whether differential CoREST constructs (CoREST1/RCOR1) altered KDM1A catalytic efficiency toward peptide substrates. Using various truncated CoREST constructs, we observed no statistical difference in catalytic efficiency, suggesting that this binding partner does not control activity toward the minimal substrate footprint. This result supports the idea that KDM1A catalytic activity is modular in nature, as it often exists as a member of multiprotein complexes that dictate function.19 We should note that KDM1A catalytic efficiency and substrate specificity might be further altered if chromatin or nucleosomes are utilized as substrates.22 In fact, Tan and co-workers recently illustrated that the KDM1A/CoREST-C complex has a >25-fold increase in catalytic efficiency when site-specifically methylated nucleosomes with extranucleosomal DNA are used as substrates, a phenomenon driven by Kmapp.19 Despite this evidence, there appears to be further confounding aspects to the regulation of KDM1A activity. For example, CoREST paralogs (CoREST2/RCOR2 and CoREST3/RCOR3) were recently shown to alter KDM1A activity toward nucleosomal substrates as assessed by their DNA binding ability and also affected catalytic efficiency toward peptide substrates.17,50,51 Because we are utilizing the minimal peptide substrate (H3K4me21–21) in these studies, and inhibitor potency seems to be unaffected by the presence of CoREST in vitro,23,52 we moved forward with our investigation using isolated KDM1A.

In line with our hypothesis, initial dose–response analysis of full-length H3 versus KDM1A demethylation activity suggested that the interaction was in the theoretical tight-binding limit of the assay (i.e., IC50 ≤10-fold [E]T). If we consider the basic definition of the equilibrium dissociation constant for competitive inhibitors, where Ki = koff/kon, it is easy to see that affinity is driven by either rapid association of the binary EI complex or a slow rate of release of the ligand from the target enzyme.53 To assess the onset of inhibition, we examined the initial rate data upon assay initiation. These initial rates appeared to be linear, suggesting that H3 and KDM1A reach rapid equilibrium under the specified assay conditions. Additional support for this observation came from preincubation of H3 with KDM1A. Even with extended incubation times of up to 1 h, the average IC50 did not change significantly. To assign the modality of full-length H3, we next determined the IC50 of H3 over a wide range of substrate concentrations.53

Our data support the possibility that the binding of full-length histone H3 to KDM1A is competitive in nature and displayed a nearly 100-fold increase in binding affinity (Ki = 18.9 ± 1.2 nM) as compared to that of the 21-mer product peptide. This value of magnitude increase strongly suggests some form of additional product recognition with the full-length histone and time dependence of the binding interaction. We therefore looked to investigate the source of this increase in observed binding affinity as low Ki values typical of tight-binding inhibitors are driven mainly by very slow rates of complex dissociation (i.e., low values of koff) and by the related large target residence times.53

We note that the increase in binding affinity of the H3/KDM1A interaction may be at least be partially attributed to the long residence time, as the t1/2 of the interaction was determined to be 9.63 min, corresponding to a koff of 1.2 × 10−3 s−1. Additionally, we independently confirmed the tight-binding nature of the interaction and slow rate of dissociation of the binary complex with SPR experiments in which histone H3 was immobilized to the chip surface via interaction with a C-terminus-specific antibody. Importantly, our assessment that an increasing ionic strength results in an increase in the relative IC50 suggests that the interaction of full-length histone H3 with both the flavin-containing active site and secondary exosite is electrostatic in nature. Notably, there are several regions on the surface of KDM1A that are electronegative in nature and could thereby provide the secondary binding site for histone H3.

Consistent with our proposal of a secondary binding site on the enzyme surface of KDM1A, the paralog KDM1B contains such a site that was identified through crystallographic efforts.54 Additionally, we envision that this secondary binding site may play a role in the “stick-and-catch” model recently proposed by Mattevi and co-workers.17 Here, KDM1A can probe a nucleosomal substrate using both its active site and secondary recognition element and lock the complex into a competent binding mode. On the other hand, after demethylation, the secondary binding site is expected to contribute to the stability of the nucleosome/demethylase complex. Importantly, KDM1A can remain bound to genetic loci on time scales that are in line with large-scale chromatin rearrangement.2 Upon formation of this stable product complex, KDM1A can “lie in wait” and serve as a docking element for protein, transcription factor, or repressor recruitment as first suggested by Forneris and co-workers.22,55 These proteins can then cause concomitant gene expression or repression or facilitate the dissociation of KDM1A from the product complex. The role of KDM1A as a docking module is also consistent with the observation that demethylation activity at specific estrogen responsive elements (EREs) is required for ERα recruitment and concomitant target gene expression.56,57 Our observations of an increased binding affinity for full-length products and target residence time have implications not only in the role of KDM1A as a docking element but also in the kinetic mechanism of the enzyme.

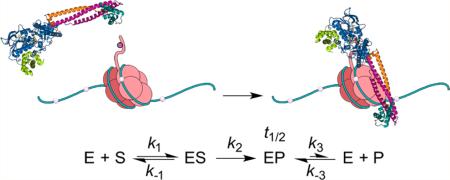

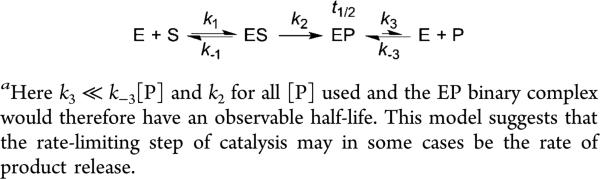

Because of the time scale of dissociation of the H3/KDM1A binary complex, we also suspect that the overall demethylation reaction in vivo and in vitro may be either partially or wholly rate-limited by product release with full-length histones or nucleosomes (Scheme 1). In this model, the rate of product release, k3, is much smaller than the rate of catalysis and product rebinding (k2 and k−3[P] for all [P] used, respectively), resulting in an EP binary complex with an observable half-life. Well in line with this hypothesis, there was a >5-fold reduction in kcatapp values observed when nucleosomal substrates were utilized.19 Additionally, the observation that KDM1A completely demethylates p53 (K370) in vitro but removes only a single methyl mark when this activity is probed in cell culture further supports our claim. Together, our results and those of others suggest that the product dissociation rate of KDM1A may be “tuned” by several factors, including substrate, binding partners, or splice variations to the enzyme itself.

Scheme 1.

Overview of a Simplified Model of KDM1A Substrate Turnover and Product Releasea

In summary, our kinetic study has verified the tight-binding interaction between full-length histone H3 and KDM1A, suggesting the existence of a secondary binding site on the demethylase surface. The contact between the H3 and KDM1A likely occurs through an extensive interaction interface with broad implications for enzyme function and control. As the complex also has a measurable residence time, the presence of KDM1A on specific genetic loci may be further investigated to provide insights into the order of partner protein recruitment, complex nucleation, or dissociation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Nate Nicely and Charles W. Pemble IV in the Duke Human Vaccine Institute X-ray Crystallography Shared Resource for their assistance with protein purification and preparation. We also thank Professor Karolin Luger from Colorado State University (Colorado Springs, CO) for providing expression plasmids of Xenopus laevis core histones. SPR measurement services were kindly provided by the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Biomolecular Interaction Analysis Facility under the direction of Dr. S. Munir Alam. We also thank Jennifer E. Link and members of the McCafferty laboratory for their thoughtful insight during the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was kindly supported by U.S. Department of Defense CDMRP Grant W81XWH-13-1-0400 to D.G.M., National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Training Grant T32-GM008487-19 in Structural Biology and Biophysics to J.M.B., and National Science Foundation Predoctoral Graduate Research Fellowship NSF GRFP 2011121201 to K.R.M.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 3,5-DCHBS

sodium 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxybenzenesulfonate

- 4-AAP

4-aminoantipyrine

- AOD

amine oxidase domain

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- HRP

horse-radish peroxidase

- IMAC

immobilized metal affinity chromatography

- IPTG

isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside

- KDM1A

lysine-specific demethylase 1A

- KDM1B

lysine-specific demethylase 1B

- LB

lysogeny broth

- LSD1

lysine-specific demethylase 1A

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PMT

photomultiplier tube

- PTM

posttranslational modification

- RU

response units

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SWIRM

SWI3p, Rsc8p, and Moira

- TB

Terrific Broth

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.M.B. and D.G.M. conceived this study. J.M.B. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.J.G. performed experiments. K.R.M. designed experiments. J.J.G. and K.R.M. helped analyze the data and revised the manuscript. D.G.M. designed the research, analyzed the data, revised the manuscript, and supervised all aspects of this study.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01135.

A detailed description of Materials and Methods and Figures S1–S9 (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voss TC, Hager GL. Dynamic regulation of transcriptional states by chromatin and transcription factors. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;15:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nrg3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler JS, Koutelou E, Schibler AC, Dent SY. Histone-modifying enzymes: regulators of developmental decisions and drivers of human disease. Epigenomics. 2012;4:163–177. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gozani OS. Histone Methylation in Chromatin Signaling. In: Workman JL, Abmayr SM, editors. Fundamentals of Chromatin. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 213–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paik WK, Kim S. Enzymatic demethylation of calf thymus histones. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973;51:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA, Shi Y. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature. 2005;437:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent B, Ruitu L, Murn J, Hempel K, Ferrao R, Xiang Y, Liu S, Garcia BA, Wu H, Wu F, Steen H, Shi Y. A specific LSD1/KDM1A isoform regulates neuronal differentiation through H3K9 demethylation. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubicek S, Jenuwein T. A crack in histone lysine methylation. Cell. 2004;119:903–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Y, Kim TY, Kim MS, Kim MA, Park SH, Jang YK. Nuclear import of human histone lysine-specific demethylase LSD1. J. Biochem. 2014;156:305–313. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvu042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavropoulos P, Blobel G, Hoelz A. Crystal structure and mechanism of human lysine-specific demethylase-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:626–632. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Wan K, Yamane K, Zhang Y, Lei M. Crystal structure of human histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13956–13961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606381103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang S, Schmitt AA, Luteran AE, Toone EJ, McCafferty DG. Thermodynamic characterization of the binding interaction between the histone demethylase LSD1/KDM1 and CoREST. Biochemistry. 2011;50:546–557. doi: 10.1021/bi101776t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Zhang H, Chen Y, Sun Y, Yang F, Yu W, Liang J, Sun L, Yang X, Shi L, Li R, Li Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Yi X, Shang Y. LSD1 is a subunit of the NuRD complex and targets the metastasis programs in breast cancer. Cell. 2009;138:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang M, Gocke CB, Luo X, Borek D, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Otwinowski Z, Yu H. Structural basis for CoREST-dependent demethylation of nucleosomes by the human LSD1 histone demethylase. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi YJ, Matson C, Lan F, Iwase S, Baba T, Shi Y. Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilotto S, Speranzini V, Tortorici M, Durand D, Fish A, Valente S, Forneris F, Mai A, Sixma TK, Vachette P, Mattevi A. Interplay among nucleosomal DNA, histone tails, and corepressor CoREST underlies LSD1-mediated H3 demethylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:2752–2757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419468112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MG, Wynder C, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature. 2005;437:432–435. doi: 10.1038/nature04021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SA, Chatterjee N, Jennings MJ, Bartholomew B, Tan S. Extranucleosomal DNA enhances the activity of the LSD1/CoREST histone demethylase complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:4868–4880. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Da G, Lenkart J, Zhao K, Shiekhattar R, Cairns BR, Marmorstein R. Structure and function of the SWIRM domain, a conserved protein module found in chromatin regulatory complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:2057–2062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510949103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burg JM, Link JE, Morgan BS, Heller FJ, Hargrove AE, McCafferty DG. KDM1 class flavin-dependent protein lysine demethylases. Biopolymers. 2015;104:213–246. doi: 10.1002/bip.22643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forneris F, Binda C, Vanoni MA, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A. Human histone demethylase LSD1 reads the histone code. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41360–41365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forneris F, Binda C, Adamo A, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A. Structural basis of LSD1-CoREST selectivity in histone H3 recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20070–20074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700100200. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron R, Binda C, Tortorici M, McCammon JA, Mattevi A. Molecular mimicry and ligand recognition in binding and catalysis by the histone demethylase LSD1-CoREST complex. Structure. 2011;19:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang M, Culhane JC, Szewczuk LM, Gocke CB, Brautigam CA, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Cole PA, Yu H. Structural basis of histone demethylation by LSD1 revealed by suicide inactivation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:535–539. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luka Z, Pakhomova S, Loukachevitch LV, Calcutt MW, Newcomer ME, Wagner C. Crystal structure of the histone lysine specific demethylase LSD1 complexed with tetrahydrofolate. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society. 2014;23:993–998. doi: 10.1002/pro.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culhane JC, Cole PA. LSD1 and the chemistry of histone demethylation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou H, Yu H. Structural insights into histone lysine demethylation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010;20:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tochio N, Umehara T, Koshiba S, Inoue M, Yabuki T, Aoki M, Seki E, Watanabe S, Tomo Y, Hanada M, Ikari M, Sato M, Terada T, Nagase T, Ohara O, Shirouzu M, Tanaka A, Kigawa T, Yokoyama S. Solution structure of the SWIRM domain of human histone demethylase LSD1. Structure. 2006;14:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaweska H, Henderson Pozzi M, Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG, Fitzpatrick PF. Use of pH and kinetic isotope effects to establish chemistry as rate-limiting in oxidation of a peptide substrate by LSD1. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5440–5445. doi: 10.1021/bi900499w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aliverti A, Curti B, Vanoni MA. Identifying and quantitating FAD and FMN in simple and in iron-sulfur-containing flavoproteins. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1999;131:9–23. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-266-X:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burg JM, Makhoul AT, Pemble C. W. t., Link JE, Heller FJ, McCafferty DG. A rationally-designed chimeric KDM1A/KDM1B histone demethylase tower domain deletion mutant retaining enzymatic activity. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:2340–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tropea JE, Cherry S, Waugh DS. Expression and purification of soluble His(6)-tagged TEV protease. Methods Mol. Biol. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2009;498:297–307. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loyola A, He S, Oh S, McCafferty DG, Rinberg D. Techniques used to study transcription on chromatin templates. Methods Enzymol. 2003;377:474–499. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)77031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Flaus AJ, Waye MM, Richmond TJ. Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:301–311. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tal M, Silberstein A, Nusser E. Why does Coomassie Brilliant Blue R interact differently with different proteins? A partial answer. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:9976–9980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zor T, Selinger Z. Linearization of the Bradford protein assay increases its sensitivity: theoretical and experimental studies. Anal. Biochem. 1996;236:302–308. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt DM, McCafferty DG. trans-2-Phenylcyclopropylamine is a mechanism-based inactivator of the histone demethylase LSD1. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4408–4416. doi: 10.1021/bi0618621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Copeland RA. Mechanistic considerations in high-throughput screening. Anal. Biochem. 2003;320:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acker MG, Auld DS. Considerations for the design and reporting of enzyme assays in high-throughput screening applications. Perspectives in Science. 2014;1:56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaelis L, Menten ML, Johnson KA, Goody RS. The original Michaelis constant: translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten paper. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8264–8269. doi: 10.1021/bi201284u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrison JF. Kinetics of the reversible inhibition of enzyme-catalysed reactions by tight-binding inhibitors. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1969;185:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson PJ. A linear equation that describes the steady-state kinetics of enzymes and subcellular particles interacting with tightly bound inhibitors. Biochem. J. 1972;127:321–333. doi: 10.1042/bj1270321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Copeland RA, Basavapathruni A, Moyer M, Scott MP. Impact of enzyme concentration and residence time on apparent activity recovery in jump dilution analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2011;416:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. A high-throughput screen for aggregation-based inhibition in a large compound library. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2385–2390. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy DJ. Determination of accurate KI values for tight-binding enzyme inhibitors: an in silico study of experimental error and assay design. Anal. Biochem. 2004;327:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Straus OH, Goldstein A. ZONE BEHAVIOR OF ENZYMES: ILLUSTRATED BY THE EFFECT OF DISSOCIATION CONSTANT AND DILUTION ON THE SYSTEM CHOLINESTERASE-PHYSOSTIGMINE. J. Gen. Physiol. 1943;26:559–585. doi: 10.1085/jgp.26.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Upadhyay G, Chowdhury AH, Vaidyanathan B, Kim D, Saleque S. Antagonistic actions of Rcor proteins regulate LSD1 activity and cellular differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404292111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrios AP, Gomez AV, Saez JE, Ciossani G, Toffolo E, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A, Andres ME. Differential properties of transcriptional complexes formed by the CoREST family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:2760–2770. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00083-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mould DP, McGonagle AE, Wiseman DH, Williams EL, Jordan AM. Reversible inhibitors of LSD1 as therapeutic agents in acute myeloid leukemia: clinical significance and progress to date. Med. Res. Rev. 2015;35:586–618. doi: 10.1002/med.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Copeland RA. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. A guide for medicinal chemists and pharmacologists. Methods Biochem. Anal. 2005;46:1–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen F, Yang H, Dong Z, Fang J, Wang P, Zhu T, Gong W, Fang R, Shi YG, Li Z, Xu Y. tructural insight into substrate recognition by histone demethylase LSD2/KDM1b. Cell Res. 2013;23:306–309. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forneris F, Binda C, Dall'Aglio A, Fraaije MW, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A. A highly specific mechanism of histone H3-K4 recognition by histone demethylase LSD1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35289–35295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pollock JA, Larrea MD, Jasper JS, McDonnell DP, McCafferty DG. Lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 inhibitors control breast cancer proliferation in ERalpha-dependent and -independent manners. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:1221–1231. doi: 10.1021/cb300108c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia-Bassets I, Kwon YS, Telese F, Prefontaine GG, Hutt KR, Cheng CS, Ju BG, Ohgi KA, Wang J, Escoubet-Lozach L, Rose DW, Glass CK, Fu XD, Rosenfeld MG. Histone methylation-dependent mechanisms impose ligand dependency for gene activation by nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;128:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.