Abstract

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients have not attained the same improvements in overall survival that either younger children or older adults have. One possible reason for this disparity may be that the AYA cancers exhibit unique biological characteristics resulting in differences in clinical and treatment resistance behaviors. This report from the biological component of the jointly sponsored NCI and Live Strong Foundation workshop entitled Next Steps in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology” meeting summarizes the current status of biological and translational research progress for five AYA cancers; colorectal cancer (CRC) breast cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), melanoma and sarcoma. Conclusions from this meeting included the need for basic biological, genomic and model development for AYA cancers, as well as translational research studies to elucidate any fundamental differences between pediatric, AYA and adult cancers. The biological questions for future research are whether there are mutational or signaling pathway differences for example between adult and AYA colorectal cancer that can be clinically exploited to develop novel therapies for treating AYA cancers and to develop companion diagnostics.

Keywords: ALL, breast, colorectal, melanoma, sarcoma

Introduction

While survival rates have improved significantly over time for patients with a diverse variety of cancers across the age spectrum, adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients, from 15 to 39 years of age, have not attained the same improvements in overall survival achieved in either younger children or older adults. One reason for the limited progress in overall outcomes for cancers arising in AYA patients compared to the same diseases in younger and older individuals may be that the AYA cancers exhibit unique biological characteristics.1–2 In 2006 the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Progress Review Group (PRG) on AYA oncology recommended investigating the potential biological basis of age-related differences in outcome for AYA cancers. As part of the ongoing efforts by the NCI to follow up on the recommendations of the PRG a comprehensive meeting on AYA cancers was sponsored by the NCI on September 16 and 17, 2013. This report from the biological component of the meeting summarizes the current status of biological and translational research progress for five AYA cancers for which there is the best evidence for a biological difference between AYA and adult cancers; colorectal cancer (CRC) breast cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), melanoma and sarcoma, and outlines a strategic plan for furthering our basic and clinical knowledge of AYA cancers.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

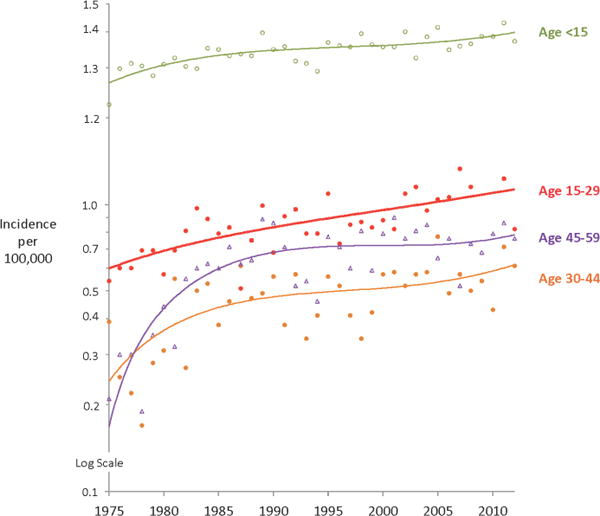

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common cancer in individuals from birth to 21 years of age and is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality in AYA patients.3–6 While the incidence of ALL in the United States in children from age 1 to 10 years has remained relatively constant over the past several decades, data from the NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (http://seer.cancer.gov) reveal a continual increase in the incidence of ALL in the AYA population (ranging in age from 15 to 29 years) from 1975 to 2010 (Figure 1). Whether this apparent increase in incidence is due to improved reporting or reflects a true increased incidence of disease remains to be determined. The difference may also reflect the changing ethnic composition of the US population as persons of self-described Hispanic ethnicity have the highest incidence rates of ALL and the incidence rate of ALL in this ethnic group is increasing compared to all other racial and ethnic groups (SEER.cancer.gov). Unfortunately, in contrast to pediatric ALL where scientific and clinical advances have led to impressive improvements in overall survival with more than 85% of children now achieving cure on contemporary chemotherapy regimens, overall survival in AYA ALL remains very poor. Less than 45% of AYA ALL patients currently achieve long-term remissions. While ALL is one of several cancers with a very poor outcome in the AYA population, ranked as fourth among the AYA cancers with the lowest overall survival rates it remains the most common cause of AYA cancer-related mortality due to its significantly higher incidence in this age group (http://seer.cancer.gov).

Figure 1.

Annual incidence of ALL in various age groups (SEER,cancer.gov).

The impact of age on relapse-free and overall survival in ALL is very striking, and age remains one of the most important prognostic factors for outcome.4 NCI SEER data as well as data from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) demonstrate that survival from ALL begins to decrease dramatically after about 15–16 years of age.4–5 Whether the differences in outcome observed in pediatric vs. AYA ALL patients are due to distinct genetic and biologic features of the disease at different ages, differences in therapeutic approach and therapeutic intensity, potential differences in compliance to therapy at different ages, and/or other social, behavioral or other factors is now under intensive investigation.3–4

In contrast to children, the impact of race and ethnicity on the incidence and mortality of ALL in the AYA population had been understudied and is an important area for future investigation. Consortium investigators involved in the NCI TARGET Project on High-Risk ALL (https://ocg.cancer.gov/), COG, and St. Jude Children’s Hospital have published a number of recent studies using comprehensive genomic approaches and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) which have identified specific germ-line genetic polymorphisms and genes, many of which are highly associated with race and ethnicity, that are associated with an increased incidence or mortality in pediatric ALL.7–16 In their most recent studies, these investigators focused on AYA ALL and performed a GWAS study to comprehensively identify inherited genetic variants associated with susceptibility to AYA ALL. In the discovery GWAS, these investigators compared the genotype frequency at 635,297 SNPs in 308 AYA ALL cases and 6,661 non-ALL controls by using a logistic regression model with European, African and Native American genetic ancestries as a covariates. SNPs that reached association P≤ 5×10−8 in the discovery GWAS were tested in an independent cohort of 162 AYA ALL cases and 5,755 non-ALL controls. A single susceptibility locus was identified on chromosome 10p14, signified by two SNPs within the GATA3 gene with genome-wide significant associations: rs3824662. These findings were validated in an independent replication cohort. The risk allele at rs3824662 was most frequent in Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-like ALL but also conferred susceptibility to non-Ph-like ALL in AYA patients. Interestingly, this GATA3 risk allele is more prevalent in patients with Hispanic ethnicity. In 1,827 non-selected ALL cases, the risk allele frequency at this SNP was positively correlated with age at diagnosis. As the first GWAS of ALL susceptibility in the AYA population, these results point to the unique biologic features that underlie ALL in this age group.

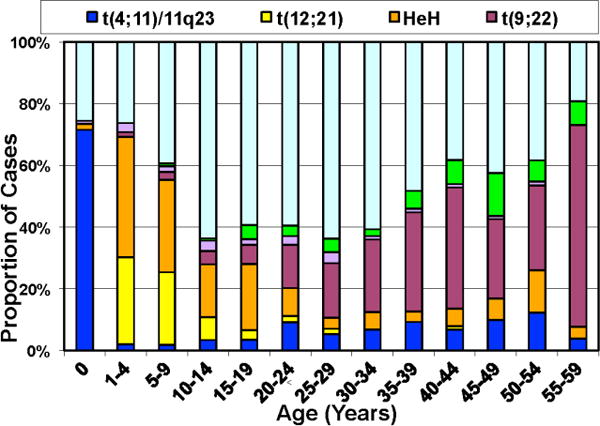

While the genetics of pediatric ALL have been studied in great detail, the biologic determinants of treatment failure in ALL patients of any age remain poorly understood. ALL may be of B- or T-cell lineage and have recurring characteristic chromosomal alterations and somatic sequence alterations. These alterations include aneuploidy (e.g., high hyperdiploidy (HeH) or hypodiploidy) and chromosomal rearrangements that commonly disrupt hematopoietic regulators or aberrantly active oncogenes and tyrosine kinases (e.g., ETV6-RUNX - t(12;21); TCF3-PBX1 - t(1;19); BCR-ABL1 – t(9;22), and translocation of the 11q23 gene MLL – frequently t(4;11) and other variants) in B-ALL and rearrangement of TAL1, TLX1, and TLX3 in T-ALL.17–18 Several of these genetic alterations are typically associated with a significantly increased risk of treatment failure and relapse on current treatment regimens (e.g., MLL rearrangements, BCR-ABL1, and low hypo-diploidy). Importantly, as shown in Figure 2, the frequency of genomic rearrangements is associated with a superior outcome (e.g., ETV6-RUNX1- t(12;21) and high hyper-diploidy in pediatric ALL decrease in AYA ALL patients, while those genetic abnormalities associated with a poorer outcome (BCR- ABL1 – t(9;22), MLL rearrangements) and Ph-like ALL increase.17 Importantly, a substantial number of children with ALL, particularly those who are older than 10 years of age, and AYA ALL patients, including many who relapse, lacked one of these sentinel, well-known chromosomal alterations. To discover the underlying genetic abnormalities in these forms of high-risk pediatric ALL and AYA ALL, the NCI TARGET Project in High Risk ALL (https://ocg.cancer.gov/) was formed with a consortium of investigators from COG, University of New Mexico, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. This team of investigators used several integrated genomic approaches including gene expression profiling and next generation sequencing methods including whole exome, whole genome, and transcriptomic (RNAseq) sequencing to uncover novel underlying genetic abnormalities in high risk pediatric and AYA ALL.7–8,19–28 These investigators were able to perform comprehensive genomic analysis on leukemic samples from >1300 pediatric ALL patients accrued to COG or St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Clinical Trials, including >800 high risk ALL patients with a mean age of 13.5 years. In addition, they have generated more than 50 new human-murine xenograft and primagraft models of ALL to further dissect the biologic and functional consequences of novel mutations being discovered in this disease and to serve as pre-clinical animal models to test potential therapeutic interventions. Using gene expression profiling (GEP) and other genomic methods, this group first discovered pediatric ALL cases with a “BCR-ABL1-like” or “Philadelphia chromosome-like, (Ph-like)” gene expression signature6–7,18,21 that was described simultaneously by a group from the Netherlands and is associated with a significantly increased risk of treatment failure and death. These different names for the same phenotype or GEP each reflect the similarity of this novel GEP to that of ALL cases containing the classic Philadelphia (“Ph”) chromosome translocation (t(9;22) or BCR-ABL1). However, while Ph- like ALL cases lack the classic Ph chromosome translocation, they contain one or more of a complex array of novel genomic mutations in genes encoding tyrosine kinases or genes which regulating tyrosine kinase signaling pathways.20–21,23,26,28–29 Nearly 50% of pediatric Ph-like ALL cases are characterized by novel genomic rearrangements of CRLF2 such as IGH-CRLF2, P2RY8-CRLF2 and about half of CRLF2-rearranged cases also have mutations of the JAK family of tyrosine kinases, which cooperate to promote leukemogenesis. Using transcriptomic sequencing methods, these investigators have recently also discovered that Ph-like ALL cases lacking CRLF2 genomic rearrangements or JAK mutations have a complex and heterogeneous spectrum of mutations in the SH2B3, IL7R genes or cryptic translocations and gene fusions involving a number of unique partner genes fused to several different tyrosine kinases including ABL1, ABL2, PDGFRB1/2, JAK2, EPOR, and CSF1R.26,29 Thus, the underlying genomic/genetic heterogeneity in Ph-like ALL is very complex. A recently published study of a large cohort of pediatric and AYA ALL cases showed that the incidence of Ph-like ALL increases across this age spectrum, from 10–13% among children, to 21% among adolescents, and to 27% among young adults 21–39 years old with ALL. In addition to the discovery of the Ph-like ALL subgroup, this team of investigators have also discovered a large spectrum of additional novel, and potentially targetable, mutations in high-risk ALL including NRAS and KRAS.23,28

Figure 2.

Variable frequency of recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in B-ALL with patient age.

The recent publication by Roberts et al.29 is part of an effort to characterize the genomics of ALL across the age range from birth to 39 years of age. This group has assembled a cohort of over 2000 patients with ALL including over 350 adolescents 16 to 20 years old and over 150 young adults 21 to 39 years old from the COG, St. Jude, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and the Alliance - CALGB trials. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray analysis and gene expression profiling was performed to identify copy number alterations and distinct genetic subgroups. As expected, ETV6-RUNX1 (2–4% in AYA) and hyperdiploid (11% in adolescents) ALL were less frequent than in childhood ALL (<16 years; 25%). The outcome of BCR-ABL1 and Ph-like ALL was markedly inferior to other ALL subtypes. IKZF1 alterations, a marker of poor outcome in childhood ALL, were enriched in BCR-ABL1 and Ph-like ALL (70% and 77%, respectively) compared to non Ph-like patients (26%), and correlated with inferior 5 year EFS in adolescents and young adults. Interestingly, different genetic abnormalities were observed in children vs. AYA Ph-like ALL cases with a higher frequency of fusions involving ABL class genes such as ABL1, ABL2, CSF1R, and PDGFRB in children and a higher frequency of JAK2 translocations in AYA patients. Collectively, the kinase-activating BCR-ABL1 and Ph-like subtypes confer a poor prognosis and make up ~60% of AYA and young adult ALL patients29. The identification of these patients at diagnosis will provide an opportunity to incorporate tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment into current chemotherapeutic regimens, and will hopefully significantly improve the treatment outcome for AYA ALL.

These studies identify several critical molecular targets in AYA ALL. As discussed above, ongoing studies in ALL xenograft/primagraft models and in human patients have demonstrated that some of the gene fusions in Ph-like ALL involving tyrosine kinases are exquisitely sensitive to various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as imatinib or dasatinib.20,25,27–29

While detailed genomic characterization and next generation sequencing are being used to discover novel underlying genetic abnormalities in AYA ALL cohorts29, as described herein, funds supporting the next generation sequencing studies in these cohorts have either been restricted to Ph-like ALL cases or to genes which have been known to be frequently mutated in pediatric ALL. As a number of the AYA ALL cases in the cohort of more than 800 cases have yet to have an underlying genomic lesion identified, the availability of this cohort provides an important opportunity for further unbiased whole genome, exomic, or transcriptomic sequencing to continue critical discovery efforts in AYA ALL that may lead to improved therapies and outcomes.

Melanoma

The rate of melanoma in children and adolescents is rising yearly and increases with age and incidence is rising over the past two decades. Melanoma accounts for only about 1% of all malignancies in patients less than 15 years of age compared with 7% in those between the ages of 15 and 19 years and 12% in those between the ages of 20 and 24 years. The risk of diagnosis of melanoma is greater in females compared with males among adolescence and young adults.30 Genetic susceptibility is a risk factor for developing a melanoma. In addition, factors such as the presence of giant congenital melanocytic nevi, Xeroderma pigmentosum, dysplastic nevus syndrome and immunosuppression and treatment for another childhood cancer are are all associated with a greater risk for developing a melanoma.30 Important prognostic criteria for adult melanoma are Breslow’s thickness, ulceration, sentinel lymph nodes (SNL) status, and presence of metastases; however comprehensive staging guidelines have not been established for children and adolescents with melanoma. High mitotic rate and younger age are also considered to be important predictors of outcome.31 The histologic types of melanoma vary significantly between young patients and adults. Many benign skin lesions commonly seen in the young age group such as blue nevi, proliferating congenital nevi, melanocytic tumors with ambiguous histology and especially Spitz nevus share histopathological features with adult melanomas. Therefore, diagnosis of melanoma in children and AYA group can be difficult because it frequently presents as melanoma with spitzoid features such as little or no asymmetry, wedge-shaped morphology, Kamino bodies, epidermal hyperplasia and others. Molecular techniques such as comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), PCR-based LOH study, next generation sequencing analysis, mutational analysis and immunohistochemical markers could potentially improve criteria to differentiate between these benign and malignant melanocytic lesions.32

Melanoma in pediatric and AYA patients is distinct from adult melanoma with respect not only to histologic characteristics but also clinical behavior that together, suggest that a different biology may contribute to the development of melanoma in young individuals. Prognosis and overall survival rates in the pediatric and AYA groups is generally believed to be similar to that in adults, however melanoma lesions appear to be thicker in young patients at the time of presentation.33 Metastases to SNL are found more frequently in children and AYA groups than would be expected in adults with the same stage of disease although some studies might have been adjusted for melanoma thickness in these two groups.34 Also, melanoma in young patients is less likely to recur in distant organs. These data suggest that melanoma in young is more prone to progression and subsequent metastasis reflecting differences in time to diagnosis or in the biology of the disease.35

Most melanoma patients (>80%) present with localized disease at diagnosis; the remainder either have regional lymph node disease (10% to 15%) or distant metastasis (1% to 3%).36 Melanoma that has spread to distant sites is rarely curable with standard therapy, including chemotherapy or biological agents such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) or interferon (IFN-α2b).37 At present, AYA group patients, including melanoma, are treated under guidelines developed for older adults without validated outcome analysis for this population. In fact, AYA patients are more similar to pediatric than adults patients as they can withstand more intensive treatments. For example, adolescents with lymphoblastic leukemia had a better outcome when treated as high-risk patients in a pediatric protocol suggesting that they may tolerate higher doses and toxicity than older patients, and thus they are under-treated.38 These observations suggest that the outcome for younger patients may be improved over those of adults but it needs to be studied in clinical trials of adequate size and maturity, with stratification for age.

Different biology might underlie differences in clinical behavior of melanoma in adolescent patients as compared to adult melanoma. Adult melanoma typically contains complex genotypic abnormalities including frequent deletions of chromosomes 9p (the most common aberration in melanoma harboring p16), 6q, 10q and 8p and gains of chromosomes 1q, 6p, 7q, 8q, 6p, 17q and 20q. In contrast, Spitz nevus, blue nevi, proliferating congenital nevi or other benign melanocytic lesions are characterized by absence of chromosomal aberrations or have a restricted set of aberrations with no overlap with adult melanoma. The majority of Spitz nevi have a normal karyotype when analyzed by CGH with exception of gains of chromosome 11p locus corresponding to the location of HRAS that are a recurrent in a subset of Spitz nevi.39 Thus, CGH and FISH represent promising diagnostic tests ancillary to histological evaluation for problematic melanocytic lesions. Pediatric melanoma cases also show higher levels of microsatellite instability than adults with melanoma.40

Somatic mutations in proto-oncogenes BRAF, RAS, KIT and tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A, TP53, and PTEN have been implicated in melanoma development. Somatic mutations in BRAF are the most common genetic alterations occurring in up to 60% of adult cutaneous malignant melanomas and common benign melanocytic nevi (80%).41–42 Smaller series of pediatric melanomas show 87% pediatric/AYA conventional melanoma harbor activating BRAF mutations.43 Similarly, spitzoid melanomas show BRAF and NRAS mutations in majority of the cases whereas no HRAS mutations were detected. In contrast, Spitz nevi frequently harbor HRAS mutations, but completely lack BRAF and NRAS mutations. Thus, the presence of HRAS mutations would favor the diagnosis of Spitz nevus and the combined BRAF and NRAS mutational analysis would strongly argue for the diagnosis of spitzoid melanoma. However, studies examining BRAF/NRAS mutations in a large series of spitzoid melanocytic lesions are needed to confirm these data and to clarify the inconsistencies between published studies. For those lesions that do not have mutation of any of these three genes, mutation analysis in other genes such as PTEN, CDKN2A, and TP53 may increase the sensitivity of mutation analysis to enable the diagnosis. Gain of KIT may also be associated with metastasis of pediatric melanoma.44

Copy number loss at the 9p21 chromosomal locus containing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A tumor suppressor gene (CDKN2A) is frequently seen in melanoma, but not in conventional Spitz nevi. Consequently, spitzoid melanomas demonstrate more frequent loss of the CDKN2A gene product p16 whereas high levels of p16 expression are detected in Spitz nevi.45 Loss of functional p16 results in dysregulation of the cell cycle and is indicative of a poorer prognosis in patients with melanoma. CDKN2A gene is a melanoma susceptibility gene that is also postulated to have a particular relevance to early-onset familial melanoma.46 Greater expression of cyclins-CDK-D1, D4 and D6 in spitzoid tumors could also be explored to identify melanoma specimens in young age groups.

Recent findings implicate that the differential biology of melanoma at different ages is driven, in part, by deregulation of microRNA expression that target proliferation including MAP3K5, the RAS-related gene RAB32, SOC1, inflammation related genes, EMT-transition, stroma and TNF related proteins.47 Several miRNA species have been identified to be up-regulated or down-regulated in these different age groups. miRNA profiles in the primary melanomas potentially are associated with the clinical parameters of stage and nodal involvement that differ in adult and young populations suggesting that adult melanoma patients rely on different pathways of invasion than young adult melanomas.

In summary, diagnosis and treatment of melanoma in AYA population requires new approaches, since at present our knowledge is based on data extrapolated from the adult population. The lack of objective histological criteria in Spitz tumors illustrates the need for additional parameters to properly classify challenging melanocytic lesions. The molecular data strongly indicate genetic underlying between Spitz nevi and spitzoid melanomas that can be exploited as markers to distinguish between benign and malignant spitzoid lesions. Molecular markers may be useful as additional diagnostic tools to identify subgroups with more predictable outcome. It is likely that the use of CGH, FISH, and PCR- based LOH assessing chromosomal aberrations, mutations in the BRAF, NRAS, and HRAS genes, next generation sequencing and immunohistochemical approaches (e.g. p16) could prove diagnostically useful and improve molecular pathology of primary tumor and SLN biopsy provided they are validated in large cohorts with clinical follow-up.42

To improve the outcome for younger patients’ specific AYA cohorts on melanoma trials should be included in order to obtain prospective data for this population. Extrapolating data from adult trials with a mean age of 50 and applying the results to the young adult and the adolescent population will likely miss some unique factors in the younger groups. Also unknown is whether the extremely high number of somatic mutations found in adult melanomas secondary to ultraviolet light damage will also be seen in AYA melanomas. Improved knowledge of the biology of tumors in this population could successfully segregate patients with melanoma into subpopulations for specific treatments with improved outcome. Again, formal testing of novel treatment modalities such as targeted therapies and immunotherapy approaches is required in AYA age group. If specific targets could be found and clinically validated blocking mutated gene products using specific inhibitors offers a potential therapeutic approach for spitzoid melanomas. This is similar to adult melanoma in which targeting mutated BRAF and MEK demonstrates dramatic responses. At present, it is unknown whether specific inhibitors are effective in NRAS mutated melanomas in children, or HRAS mutated spitzoid tumors. The clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors has been shown in adults with melanoma, and the efficacy of anti-Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA-4) monoclonal antibody ipilimumab is being tested in adolescent patients in an ongoing phase II study opened in 2012 (NCT01696045).

Sarcoma

Fusion positive sarcomas (FPS) are a heterogeneous group comprising of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS), Ewing sarcoma, synovial sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, myxoid liposarcoma angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, myxoid chondrosarcoma, liposarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, endometrial stromal sarcoma, congenital fibrosarcoma, mesoblastic nephroma, and small round-cell sarcoma (Table 1).48 The exact incidence of these types of cancers with respect to age varies with diagnosis. The total incidence of non-Kaposi soft tissue sarcomas increases steadily with age, mostly for non-fusion gene related FPS.49

Table 1.

Associated gene fusions in sarcoma.

| Sarcoma type | Cytogenetics | Fusion genes | Gene | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiomatoid fibrous Histiocytoma | t(2;16)(q34;p11) | FUS-CREB1 | bZIP | 89% |

| Angiomatoid fibrous Histiocytoma | t(12;16)(q13;p11) | FUS-ATF1 | bZIP | 11% |

| Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma | t(X;17)(p11;q25) | ASPSCR1-TFE3 | microphthalmia-TFE, basic helix-loop helix, leucine zipper | 100% |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | t(2;2)(q35;p23) | PAX3–NCOA1 | Paired box/homeodomain | Rare |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | t(2;13)(q35;q14) | PAX3-FKHR | Paired box/homeodomain | 95% |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | t(1;13)(p36;q14) | PAX7-FKHR | Paired box/homeodomain | 5% |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | EWSR1-FLI1 | Ets-like | 85% |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(21;22)(q22;q12) | EWSR1-ERG | Ets-like | 10% |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(7;22)(p22;q12) | EWSR1-ETV1 | Ets-like | rare |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(17;22)(q12;q12) | EWSR1-ETV4 | Ets-like | rare |

| Ewing sarcoma | t(2;22)(q33;q12) | EWSR1-FEV | Ets-like | rare |

| Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor | t(11;22)(p13;q12) | EWSR1-WT1 | Zinc finger | 95% |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | t(1;2)(q25;p23) | ALK-TPM3 | Tyrosine kinase | not known |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | t(2;19)(p23;p13) | ALK-TPM4 | Tyrosine kinase | not known |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | t(2;17)(p23;q23) | ALK-CLTC | Tyrosine kinase | not known |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | t(12;16)(q13;p11) | FUS-DDIT3 | bZIP | 95% |

| Myxoid liposarcoma | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | EWSR1-ATF1 | bZIP | 5% |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | t(9;22)(q22;q12) | EWSR1-NR4A3 | bZIP | 75% |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | t(9;15)(q22;q21) | TFC12-NR4A3 | basic helix-loop helix | not known |

| Myxoid chondrosarcoma | t(9;17)(q22;q11) | TAF15-NR4A3 | bZIP | not known |

| Clear Cell Sarcoma | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | EWSR1-ATF1 | bZIP | not known |

| Liposarcoma | t(12;16)(q13,p11) | FUS-ATF1 | bZIP | not known |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;18)(p11;q11) | SYT-SSX1 | Kruppel-associated Box | 65% |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;18)(p11;q11) | SYT-SSX2 | Kruppel-associated Box | 35% |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;18)(p11;q11) | SYT-SSX4 | Kruppel-associated Box | rare |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;20) | SS18L1-SSX1 | Kruppel-associated Box | rare |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X;20) | SS18L1-SSX2 | Kruppel-associated Box | rare |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans | t(17;22)(q22;q13) | COL1A1-PDGFB | Tyrosine kinase | not known |

| Endometrial stromal sarcoma | t(7;17)(p15;q21) | JAZF1-JJAZ1 | Polycomb group Complexes | not known |

| Congenital fibrosarcoma and mesoblastic nephroma | t(12;15)(p13;q25) | EVT6-NTRK3 | HLH, Tyrosine Kinase | not known |

| Small round-cell sarcoma | inv 22q | EWSR1-ZSG | Zinc finger | not known |

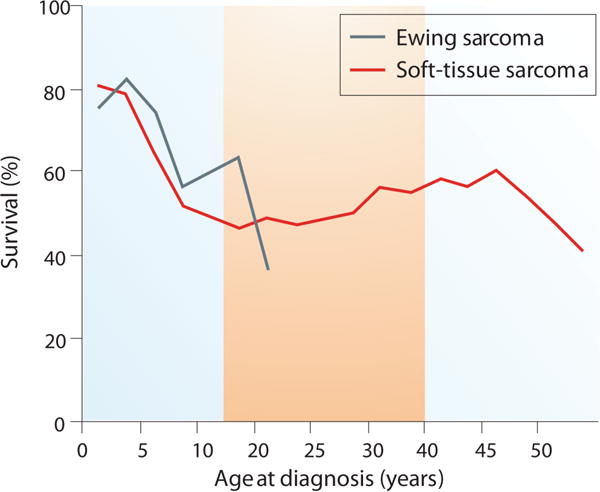

The prognosis for AYA patients with STS is generally poorer than when the disease is seen in younger patients and Figure 3 modified from previously published data50. In one of the first multivariate analyses of prognostic factors in Ewing sarcoma, survival was found to be inversely proportional to age and size of tumor at presentation. In a large randomized trial of 518 patients with Ewing sarcoma, conducted by COG, older patients were noted to have a worse outcome.51 Host age, biology of tumor, enrollment on clinical trials, and treatment intensity may all play a role in the poor prognosis of AYA patients with FPS. Until recently there have been very few systematic attempts to perform comprehensive genomic investigations of these cancers. The NCI is launching a screen for a direct inhibitor of the PAX3-FOXO1 transcription factor, and a recent study evaluating the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitor, cediranib, in patients with advanced un-resectable ASPS demonstrated an overall response rate of 35% with a disease control rate of 84% at 24 weeks. A total of 46 patients were treated with the median age of 27 years (range 19–58 years). Paired tumor biopsies were obtained from 8 AYA patients, prior to initiating therapy with cediranib and during the first week. Microarray analysis and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) were performed to demonstrate baseline expression of genes and their modulation with therapy. Primary microarray data is available at Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE32569). Twenty-nine of the top-100 differentially expressed genes were significantly modulated following treatment with cediranib. Of these, genes involved in vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and the inflammatory response, such as ANGPT2, FLT1, FOLH1, and CXCR7 were significantly down- regulated.52 There is a need for both basic biological and translational research studies to elucidate any fundamental differences between adult and AYA fusion positive cancers. Most of the fusion oncogenes involve transcription factors so biological questions include what pathways are disrupted by the fusion oncogenes, how do they lead to cancers, and how can these be targeted? For example, the exact function of the TFE3 protein in ASPS is not known, however, the tumor- specific ASPL-TFE-3 fusion transcription factor is known to directly up-regulate MET.53 Similarly FGFR4, MET, and other tyrosine kinase genes are known downstream targets of the PAX3/7-FOXO1 found in ARMS.54–56 Good animal models need to be developed for these FPSs. In most cases the fusion oncogene is diagnostic of the cancer regardless of the age of the patients, however there is a need to systematically determine incidence, and outcome of FPS with age. In most cases studies so far the tumors are dependent for survival on these fusion genes. Recently through a drug screening approach mithramycin was found to directly inhibit the EWS-FLI1 is a transcription factor.57 A tumor-specific fusion protein is an ideal target that is not expressed in normal cells and appears to be required for the oncogenesis of most fusion positive FPS; however, the ability to target these fusions has remained a challenge. Unlike the commonly targeted receptor tyrosine kinases, fusion protein transcription factors have been more difficult to target. Peptides spanning the unique fusions in Ewing sarcoma and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma have been used as part of vaccine strategies in consolidative immunotherapy58, but did not result in robust immune responses. The Ewing sarcoma translocation EWS-FLI1 results in a transcription factor that requires binding to RNA helicase A for oncogenic function. Strategies to inhibit interaction with RNA helicase A are underway.59 Since anti-VEGFR therapy has shown activity in ASPS and MET is overexpressed in this disease, an NCI clinical trial is evaluating the agent, caboxantinib, a dual inhibitor of VEGFR and MET, is being evaluated [NCT01755195]. A sarcoma cell line screen has been conducted generating concentration response data to 100 FDA approved anticancer drugs and about 350 investigational agents. Twenty-two out of the 63 sarcoma cell lines screened were from patients in the AYA age-group.60–61 Comprehensive genomic analysis including whole genome, whole exome, transcriptome, and the epigenetic landscape are required for these tumors. Investigating the downstream impact of the fusion genes using RNA-Seq, and chromatin immunoprecipitate sequencing (ChIPseq) will reveal important insights into the biology of these cancers.

Figure 3.

Poor prognosis for AYA patients compared younger patients with soft tissue sarcomas.

Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

The incidence of AYA CRC is low compared to that of older adults, comprising 2% to 6% of cases. However, AYA CRC is the fourth leading cause of AYA cancer deaths resulting in approximately 800 deaths annually.62 It is known that AYA CRC patients have a poorer prognosis and exhibit a more aggressive disease phenotype than CRC in older adults.50,63 AYA CRC exhibits a greater frequency of mucinous histology, signet ring cells, high microsatellite instability (MSI- H), and a higher incidence of mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes.64–69 The current studies investigating the molecular characterization of this tumor include those summarized in a publication from an NCI workshop that focused on several AYA cancers.1 However, relatively few molecular genetic studies of CRC have been conducted in this age group, perhaps due to the fact that these cases are few in number and tissue samples may be difficult to procure. Recent work by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has provided data on genes that are frequently mutated in adult CRC.70 This and other studies have also identified several genes that exhibit amplification and elevated expression in adult CRC, including IGF2.71 There are also consensus gene sets that exhibit mutations in adult CRC.62,72–73 These data provide a baseline for pathway analysis that could direct us toward novel signaling pathways in AYA CRC tumors. There is a need for both basic biological and translational research studies to elucidate any fundamental differences between adult and AYA CRC. The biological questions include whether there are signaling pathway differences between the two types of CRC, and if so how unique are they to each form of the disease, and how dependent are the tumor cells on these pathways for their proliferation and survival? The only molecular marker that could be considered a predictor in AYA CRC is MSI, which is also associated with Lynch Syndrome. However, MSI and mucinous histology are more descriptive than predictive. True diagnostic markers that are specific to AYA CRC have yet to be identified. While AYA CRC tends to have a more mucinous phenotype, and appears to have a higher frequency of MSI even in the absence of a hereditary component, molecular targets that would make the AYA CRC more vulnerable to a specific therapeutic target have yet to be identified. High throughput methodologies for gene expression and mutational analysis would provide initial clues to whether there are unique molecular characteristics associated with AYA CRC compared to that found in adults. These analyses could include microarray analysis or transcriptomic (RNAseq) for mRNA, and miRNA expression signatures and exome sequencing studies for identification of unique somatic mutation patterns. Studies could also include single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), methylation, and proteomic analyses to compare adult and AYA forms of the disease. The results from these studies will provide a foundation from which novel diagnostic, prognostic and predictive markers can be identified in this population, and perhaps reveal preferred signaling pathways that can be used as targets for therapy.

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most frequent form of cancer in women in this age group (15- 39yrs) throughout the world.50,74–76 Interestingly, the incidence with distant involvement associated with a significantly poorer prognosis, has shown a statistically significant increase in the AYA age group in recent years.77 Age of onset is an independent risk factor for breast cancer, and cumulative evidence has suggested that AYA breast cancer exhibits differences in type, grade and aggressiveness, in comparison to the disease in older women.75,78 However the hypothesis that this was due to a unique biology has been the subject of debate.79 Breast cancer in the AYA population is rare, representing less than 1% of all cases, but when they do occur AYA breast tumors are frequently larger in size and of a higher grade. More AYA patients exhibit a triple negative subtype, which is generally more aggressive and has a poorer prognosis than other subtypes80, while the incidence of less aggressive luminal A tumors is lower.81–82 Current studies continue to utilize gene expression profiling in order to identify specific genes and molecular profiles that could identify unique factors involved in younger women with breast cancer.83–88 The results of these studies suggest that there are some expression pattern differences between tumors in young and older women, but re-analysis of some earlier studies has led to questions about some of these conclusions.75 Ongoing studies have also focused on specific genes such as BRCA1, TP53, and others that have been linked to the early incidence of aggressive breast cancer.89–90 There is also a growing interest in the role of apparent age-related differences in tumor-associated stroma.91 Studies of the molecular mechanisms of different breast cancer subgroups identified in adults are likely to be informative for AYA breast cancer as well, since no consistently unique molecular or biological factors have been definitively identified.92 Detailed studies of triple-negative/basal subgroups93 are particularly relevant since these have been more frequently associated with breast cancers in AYA population. Studies on the role of the microenvironment and stroma in initiation and progression of AYA tumors should be investigated. More extensive, carefully controlled analysis of gene expression signatures in AYA tumors and stroma relative to the same subtypes in older patients is needed to definitively determine if a specific pattern is linked to AYA breast cancers.94 Whole genome analysis with deep sequencing could also help to identify mutations or polymorphic patterns that could be linked to susceptibility to early onset breast cancer.95–96 Although no definitive markers are known to exist that would differentiate tumors in AYA patients, suggested possible linkage to ectopic BRCA1 expression, tenascin – C variants, along with other potential markers, need to be explored in more detail.91,97–99 While no specific molecular targets are known at this time, few studies of AYA breast cancer therapeutic responses have been performed100. There are currently several clinical trials specifically addressing issues in this population101–102 and whether the therapeutic response of AYA breast cancer is intrinsically different from that found in older women.103–104 Studies of factors linking obesity and other stress-inducers that could trigger molecular events contributing to the etiology of AYA breast cancer need to be studied further. Development of animal or other models of the changes occurring in breast tissue in the AYA population as the result of development, pregnancy and other factors, and how carcinogens or specific gene expression patterns contribute to the etiology of breast cancer are needed.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In order for sustained progress to take place in understanding the biology of AYA cancers, and how an understanding of that biology can be utilized for better patient treatment will require efforts in multiple directions. There is an urgent need to centrally register all patients with AYA cancers and develop a tissue repository of normal (germ-line) and malignant tissues, and develop patient derived xenografts from the most aggressive subtypes. There is also a need for basic biological, genomic and model development for these cancers, as well as translational research studies to elucidate any fundamental differences between pediatric, AYA and adult cancers. The biological questions include whether there are mutational or signaling pathway differences for example between adult and AYA colorectal cancer that can be clinically exploited. If we are able to elucidate such differences we can then begin to utilize this information to develop novel therapies for treating AYA cancers, and companion diagnostics to accompany these treatments.

Acknowledgments

Funding Disclosures: Research in this publication was supported by the NCI ARRA Challenge Grant CA145707 (C. Willman), NCI K23157728 (C. Anders)

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tricoli JV, Seibel NL, Blair DG, et al. Unique characteristics of adolescent and young adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia, breast cancer, and colon cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2011;103:628–635. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sender L, Zabokrtsky KB. Adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a milieu of unique features. Nature Reviews Clin Oncol. 2015;12:465–480. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advani AS, Hunger SP, Burnett AK. Acute leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:213–226. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stock W. Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:21–29. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullighan CG, Willman CL. Advances in the biology of acute lymphoblastic leukemia–from genomics to the clinic. J Adolesc and Young Adult Onc. 2011;1:77–86. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleyer A, Siegel SE, Coccia PF, Stock W, Seibel NL. Children, adolescents, and young adults with leukemia: the empty half of the glass is growing. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4037–4038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Chen IM, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:5312–5321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey RC, Wang X, Dobbin KK, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling: Correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116:4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang JJ, Cheng C, Devidas M, et al. Ancestry and pharmacogenomics of relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:237–241. doi: 10.1038/ng.763. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, Cheng C, Devidas D, et al. ARID5B genetic polymorphisms contribute to racial disparities in the incidence and treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:751–757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H, Yang W, Perez-Andreu V, et al. Novel susceptibility variants at 10p12.31-12.2 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in ethnically diverse populations. JNCI. 2013;105:733–742. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Cheng C, Yang W, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of germline genetic variation associated with treatment response in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2009;301:393–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treviño LR, Yang W, French D, et al. Germline genomic variations associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/ng.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JJ, Cheng C, Devidas M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies germline polymorphisms associated with relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:4197–4204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-440107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez-Andreu V, Roberts KG, Harvey RC, et al. Inherited GATA3 Genetic Variants are Associated with Ph-like Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Risk of Relapse. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:1494–1498. doi: 10.1038/ng.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Andreu V, Roberts KG, Xu H, et al. A genome wide association study of susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Blood. 2015;125:680–686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-595744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison CJ. Cytogenetics of paediatric and adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aifantis I, Raetz E, Buonamici S. Molecular pathogenesis of T-cell leukaemia and lymphoma. Nature Rev in Immunology. 2008;8:380–390. doi: 10.1038/nri2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 (IKAROS) is associated with poor prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Harvey RC, et al. JAK mutations in high risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9414–9418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullighan CG, Phillips LA, Collins-Underwood R, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 in B-progenitor and Down Syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1243–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang H, Chen IM, Wilson CS, et al. Gene expression classifiers for relapse free survival and minimal residual disease improve risk classification and outcome prediction in pediatric B- precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:1394–1405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-218560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Mullighan CG, Harvey RC, et al. Key pathways are frequently mutated in high risk B- precursor childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group NCI TARGET Project. Blood. 2011;118:3080–3087. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen IM, Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, et al. Outcome Modeling with CRLF2, IKZF1, JAK and Minimal Residual Disease in Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2012;119:3512–3522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tasian SK, Doral MY, Mullighan CG, et al. Aberrant JAK/STAT and PI3K/mTOR pathway signaling occurs in human CRLF2-rearranged B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Blood. 2012;120:833–842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-389932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts KG, Morin R, Zhang J, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maude SL, Tasian SK, Vincent T, et al. Targeting Jak1/2 and mTOR in murine xenograft models of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:3510–3518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh ML, Zhang J, Mullighan CG, et al. Tyrosine kinome sequencing of high risk pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Report from The Children’s Oncology Group TARGET Project. Blood. 2013;121:485–488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts KG, Payne-Turner D, Pei D, Becksfort J, et al. The Childrens Oncology Group ALL TARGET Project and the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital-Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Targetable kinase activating lesions in Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Eng J Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappo AS. Melanoma in children and adolescents. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2651–2661. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange JR, Palis BE, Chang DC, et al. Melanoma in children and teenagers: an analysis of patients from the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1363–1368. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dadras SS. Molecular diagnostics in melanoma: current status and perspectives. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:860–869. doi: 10.5858/2009-0623-RAR1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari A, Bono A, Baldi M, et al. Does melanoma behave differently in younger children than in adults? A retrospective study of 33 cases of childhood melanoma from a single institution. Pediatrics. 2005;115:649–654. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sondak VK, Taylor JM, Sabel MS, et al. Mitotic rate and younger age are predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity: lessons learned from the generation of a probabilistic model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:247–258. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livestro DP, Kaine EM, Michaelson JS, et al. Melanoma in the young: differences and similarities with adult melanoma: a case-matched controlled analysis. Cancer. 2007;110:614–624. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krug B, Crott R, Lonneux M, et al. Role of PET in the initial staging of cutaneous malignant melanoma: systematic review. Radiology. 2008;249:836–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2493080240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkwood JM, Jukic DM, Averbook BJ, Sender LS. Melanoma in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:419–431. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boissel N, Auclerc MF, Lheritier V, et al. Should adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia be treated as old children or young adults? Comparison of the French FRALLE-93 and LALA-94 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:774–780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastian BC, Wesselmann U, Pinkel D, Leboit PE. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of Spitz nevi shows clear differences to melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1065–1069. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uribe P, Wistuba II, Solar A, et al. Comparative analysis of loss of heterozygosity and microsatellite instability in adult and pediatric melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:279–285. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000171599.40562.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Dijk MC, Bernsen MR, Ruiter DJ. Analysis of mutations in B-RAF, N-RAS, and H-RAS genes in the differential diagnosis of Spitz nevus and spitzoid melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1145–1151. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000157749.18591.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fullen DR, Poynter JN, Lowe L, et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations in spitzoid melanocytic lesions. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu C, Zhang J, Nagahawatte P, et al. Pediatric cancer genome project: the genetic landscape of childhood and adolescent melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:816–823. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daniotti M, Ferrari A, Frigerio S, et al. Cutaneous melanoma in childhood and adolescence shows frequent loss of INK4A and gain of KIT. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1759–1768. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al Dhaybi R, Agoumi M, Gagne I, et al. p16 expression: a marker of differentiation between childhood malignant melanomas and Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansson J. Familial melanoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:897–916. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jukic DM, Rao UN, Kelly L, et al. Micro RNA profiling analysis of differences between the melanoma of young adults and older adults. J Transl Med. 2010;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aplan P, Khan J. Molecular and Genetic Basis of Chilhood Cancer. Lippinccott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. p. 1531. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casillas J, Ross J, Keohan ML, Bleyer A, Malogolowkin M. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975–2000. In: Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, editors. Soft Tissue Sarcomas. National Cancer Institute, NIH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bleyer A, Barr R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. The distinctive biology of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrc2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:694–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kummar S, Allen D, Monks A, et al. Cediranib for Metastatic Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2296–2302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P, Shukla N, McGill GG, Nagai M, Saito T, Lae M, Fisher DE, Ladanyi M. TFE3 fusions activate MET signaling by transcriptional up- regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:919–929. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor JG, Cheuk AT, Tsang PS, et al. Identification of FGFR4-activating mutations in human rhabdomyosarcomas that promote metastasis in xenotransplanted models. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3395–3407. doi: 10.1172/JCI39703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao L, Yu Y, Bilke S, Walker RL, Mayeenuddin LH, Azorsa DO, Yang F, Pineda M, Helman LJ, Meltzer PS. Genome-wide identification of PAX3-FKHR binding sites in rhabdomyosarcoma reveals candidate target genes important for development and cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6497–6508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taulli R, Scuoppo C, Bersani F, et al. Validation of met as a therapeutic target in alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4742–4749. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grohar PJ, Woldemichael GM, Griffin, et al. Identification of an inhibitor of the EWS-FLI1 oncogenic transcription factor by high-throughput screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:962–978. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dagher R, Long LM, Read EJ, et al. Pilot trial of tumor-specific peptide vaccination and continuous infusion interleukin-2 in patients with recurrent Ewing sarcoma and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: an inter-institute NIH study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:158–164. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erkizan HV, Kong Y, Merchant M, et al. A small molecule blocking oncogenic protein EWS-FLI1 interaction with RNA helicase A inhibits growth of Ewing’s sarcoma. Nat Med. 2009;15:750–756. doi: 10.1038/nm.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.August EM, Delosh R, Laudeman J, Ogle C, Reinhart R, Selby M, Silvers T, Morris J, Teicher BA. Screening of pediatric and adult sarcoma cell lines reveals novel patterns of sensitivity toward approved oncology drugs and investigational agents. Proc AACR. 2013 Abstract 5590. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monks A, Rapisarda A, Wrzeszczynski KO, August EM, Polley EC, Kondapaka SB, Kaur G, Dianne Newton D, Teicher BA. Target and drug discovery for recalcitrant, rare and neglected cancers. Proc AACR. 2013 Abstract 436. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted in the SEER web site, April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hubbard JM, Grothey A. Adolescent and young adult colorectal cancer. J Natl Comp Cancer Network. 2013;11:1219–1225. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liang JT, Huang KC, Cheng AL, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular biological features of colorectal cancer in patients less than 40 years of age. Br J Surgery. 2003;90:205–214. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu B, Farrington SM, Petersen GM, et al. Genetic instability occurs in the majority of young patients with colorectal cancer. Nature Med. 1995;1:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kakar S, Aksoy S, Burgart LJ, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the colon: correlation of loss of mismatch repair enzymes with clinicopathologic features and survival. Modern Path. 2004;17:696–700. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Durno C, Aronson M, Bapat B, Cohen Z, Gallinger S. Family history and molecular features of children, adolescents, and young adults with colorectal carcinoma. Gut. 2005;54:1146–1150. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sultan I, Rodriguez-Galindo C, El-Taani H, et al. Distinct features of colorectal cancer in children and adolescents: a population-based study of 159 cases. Cancer. 2010;116:758–765. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hill DA, Furman WL, Billups CA, et al. Colorectal carcinoma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5808–5814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tricoli JV, Rall LB, Karakousis CP, et al. Enhanced levels of insulin-like growth factor messenger RNA in human colon carcinomas and liposarcomas. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6169–6173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, et al. The consensus coding sequence of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Go RS, Gundrum JD. Cancer in the adolescent and young adult (AYA) population in the United States: Current statistics and projections. J Clin Onc. 2011;(suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anders CK, Fan C, Parker JS, Carey LA, Blackwell KL, Klauber-DeMore N, et al. Breast carcinomas arising at a young age: unique biology or a surrogate for aggressive intrinsic subtypes? J Clin Onc. 2011;29:e18–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Narod SA. Breast cancer in young women. Nature Rev Clin Onc. 2012;8:460–470. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnson RH, Chien FL, Bleyer A. Incidence of breast cancer with distant involvement among women in the United States, 1976 to 2009. JAMA. 2013;309:800–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gewefel H, Salhia B. Breast cancer in adolescent and young adult women. Clin Breast Canc. 2014;14:390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Colleoni M, Anders CK. Debate: the biology of breast cancer in young women is unique. The Oncologist. 2013;18:e13–5. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peng R, Wang S, Shi Y, Liu D, Teng X, Qin T, et al. Patients 35 years old or younger with operable breast cancer are more at risk for relapse and survival: a retrospective matched case- control study. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2011;20:568–573. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cancello G, Maisonneuve P, Rotmensz N, Viale G, Mastropasqua MG, Pruneri G, et al. Prognosis and adjuvant treatment effects in selected breast cancer subtypes of very young women (<35 years) with operable breast cancer. Annals of Onc. 2010;21:1974–1981. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keegan TH, DeRouen MC, Press DJ, Kurian AW, Clarke CA. Occurrence of breast cancer subtypes in adolescent and young adult women. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Anders CK, Acharya CR, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, Garman K, Foekens JA, et al. Age-specific differences in oncogenic pathway deregulation seen in human breast tumors. PloS One. 2008;3:e1373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anders CK, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, Acharya CR, Foekens JA, Zhang Y, et al. Young age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expression. J Clin Onc. 2008;26:3324–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Azim HA, Jr, Michiels S, Bedard PL, Singhal SK, Criscitiello C, Ignatiadis M, et al. Elucidating prognosis and biology of breast cancer arising in young women using gene expression profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1341–1351. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carvalho LV, Pereira EM, Frappart L, Boniol M, Bernardo WM, Tarricone V, et al. Molecular characterization of breast cancer in young Brazilian women. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 2010;56:278–287. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Collins LC, Marotti JD, Gelber S, Cole K, Ruddy K, Kereakoglow S, et al. Pathologic features and molecular phenotype by patient age in a large cohort of young women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res and Treat. 2012;131:1061–1066. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Azim HA, Partridge AH. Biology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Canc Res. 2014;16:427–435. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0427-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Young SR, Pilarski RT, Donenberg T, Shapiro C, Hammond LS, Miller J, et al. The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations among young women with triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:86–91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Cong H, Zhang X. The ectopic expression of BRCA1 is associated with genesis, progression, and prognosis of breast cancer in young patients. Diagnostic Path. 2012;7:181–188. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guttery DS, Hancox RA, Mulligan KT, Hughes S, Lambe SM, Pringle JH, et al. Association of invasion-promoting tenascin-C additional domains with breast cancers in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R57–R71. doi: 10.1186/bcr2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prat A, Adamo B, Cheang MC, Anders CK, Carey LA, Perou CM. Molecular characterization of basal-like and non-basal-like triple-negative breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2013;18:123–133. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Servant N, Bollet MA, Halfwerk H, Bleakley K, Kreike B, Jacob L, et al. Search for a gene expression signature of breast cancer local recurrence in young women. Clin Canc Res. 2012;18:1704–1715. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loo LW, Wang Y, Flynn EM, Lund MJ, Bowles EJ, Buist DS, et al. Genome-wide copy number alterations in subtypes of invasive breast cancers in young white and African American women. Breast Canc Res and Treat. 2011;127:297–308. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1297-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stevens KN, Vachon CM, Lee AM, Slager S, Lesnick T, Olswold C, et al. Common breast cancer susceptibility loci are associated with triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6240–6249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Phuah SY, Looi LM, Hassan N, Rhodes A, Dean S, Taib NA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) loss are predictors of BRCA1 germ-line mutations in women with early-onset and familial breast cancer, but not in women with isolated late-onset breast cancer. Breast Canc Res. 2012;14:R142–R151. doi: 10.1186/bcr3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Evans DG, Moran A, Hartley R, Dawson J, Bulman B, Knox F, et al. Long-term outcomes of breast cancer in women aged 30 years or younger, based on family history, pathology and BRCA1/BRCA2/TP53 status. British J of Canc. 2010;102:1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rath MG, Masciari S, Gelman R, Miron A, Miron P, Foley K, et al. Prevalence of germline TP53 mutations in HER2+ breast cancer patients. Breast Canc Res and Treat. 2013;139:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2375-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Freedman RA, Partridge AH. Adjuvant therapies for very young women with early stage breast cancer. Breast (Edinburgh Scotland) 2011;(Suppl 3):S146–149. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(11)70313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.NCT01468246 The Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (HOHO)- longitudinal cohort study of young women with breast cancer evaluating clinical as well as tumor biology endpoints.

- 102.NCT01503190 Immune System’s Response to Young Women’s Breast Cancer

- 103.NCT00276120 Young Women’s Breast Cancer Research Program- The purpose of this study is to identify novel genetic factors which distinguish breast cancer in younger women compared to older women.

- 104.NCT01320488 Breast Cancer in Young Women: Is it Different? Longitudinal cohort study is specifically studying genetics of breast cancer in young Saudi women.