Abstract

In facing the daunting challenge of using human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (hESCs, hiPSCs) to study complex neural circuit disorders such as schizophrenia (SCZ), mood and anxiety disorders and autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), a 2012 National Institute of Mental Health workshop produced a set of recommendations to advance basic research and engage industry in cell-based studies of neuropsychiatric disorders. This review describes progress in meeting these recommendations, including the development of novel tools, strides in recapitulating relevant cell and tissue types, insights into the genetic basis of these disorders that permit integration of risk-associated gene regulatory networks with cell/circuit phenotypes, and promising findings of patient-control differences using cell-based assays. However, numerous challenges are still being addressed, requiring further technological development, approaches to resolve disease heterogeneity and collaborative structures for investigators of different disciplines. Additionally, since data obtained so far is on small sample sizes, replication in larger sample sets is needed. A number of individual success stories point to a path forward in developing assays to translate discovery science to therapeutics development.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, induced neuronal cells, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorders, genetics, drug discovery

Introduction

Since the initial reports of human pluripotent cell isolation from blastocysts 1 and transcription factor reprogramming of somatic cells 2–5, researchers have increasingly focused on using these cells for discovery-based analysis of human disease mechanisms and developing assays to screen candidate small molecule therapeutics. This technology is particularly significant for the study of tissues, such as brain, that are rarely if ever accessible as biopsies from living patients. As a result, human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and similar reprogrammed cells are becoming an important tool in the toolbox for studying complex brain disorders. Despite the huge burden of neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (SCZ), mood and anxiety disorders like bipolar disorder (BPD), and autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), progress has remained slow in developing new therapeutics to treat these disorders. Amidst concern that Large Pharma has scaled backed portfolios for complex brain disorders 6–9, a number of pharmaceutical companies are re-calibrating their investment in these disorders through new strategies, including the incorporation of patient-derived cells into assay development.

Early evidence for such a re-calibration included an April, 2012 workshop involving academic, industry and government scientists at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). This meeting allowed investigators to share their promising unpublished data from exploratory studies of hiPSC lines derived from patients with neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, researchers discussed the potential of public-private partnerships to push the envelope in developing a new generation of cell-based assays that are rigorously designed and more reliable predictors of pathophysiological mechanisms and patient response 10. More than three years later, a large increase in published work in this sphere attests to the growing progress in using these tools to obtain better understanding and treatment of these complex brain disorders.

Principal challenges continue to be in two forms of reliability. The first challenge is to reduce variability and increase efficiency and replicability in the protocols for generating the cell lines and their derivatives, but also to increase the robustness of the assays made from the cells (which relates to issues like scalability, durability of the cells to processing, and producing strong experimental signal relative to noise). The second challenge is to obtain assays that meaningfully relate to the mechanisms of pathophysiology (i.e., ‘construct validity’) and can distinguish important differences in disease state from patient to patient. These cell-based assays provide an interesting contrast to model organism studies, which permit a systems-level approach to systems-level disorders but have a limited history of predicting clinical response or adverse effects to drugs in patients 7, 11, 12. While human/patient-derived reprogrammed cell lines should provide molecular targets equivalent to those in actual patients, there remain significant hurdles to obtaining measures that relate to systems-level pathophysiology, that stratify patients adequately or predict pharmacological and toxicological response (efficacy, tolerability). However, many new approaches have been developed that raise confidence that these are soluble problems; additionally, a path has been blazed by progress in a neurodegenerative disorder, where consistent phenotypes using hiPSC-based assays, combined with a response to an existing drug, has led to a new approved clinical trial for Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 13.

The Relative Value of Collecting Patient-Derived Lines versus Making Isogenic Lines

The area where cell-based technologies have seen the most impressive advances is in reprogramming and derivation methods; in fact, derivation methods themselves have opened up new avenues in the study of pluripotency regulation and naïve versus primed states 14, 15. Whereas the initial reports of reprogramming human somatic cells to pluripotency involved four or more transcription factors delivered by an integrating virus, further studies have diversified the factor combinations (although Oct4 and Sox2 are nearly always used), the effector molecule form (e.g., DNA, RNA, protein), the delivery method (non-integrating viruses, episomal plasmids, other packaging and delivery methods) and the use of small molecules and other adjuvants to substitute for transcription factors or to modify the efficiency of reprogramming 16. There is as yet no agreed-upon standard for the reprogramming process; for larger scale production, the decision of which method to use may depend more on technology licensing issues, ease of use and scalability. A series of international workshops and panel sessions were held between 2013 and 2015 to further address the issues involved in standardizing derivation, quality control, banking and distribution methods, along with coordination and harmonization on many practical and ethical issues ranging from generation of reference standard lines, cell line databases, subject recruitment, informed consent, intellectual property/licensing and training. These sessions were held in the context of a growing number of initiatives aimed at generating collections of hiPSC lines 17.

There are currently a number of distinct patient-derived hiPSC collections available or being made to study various complex brain disorders through the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), the European Autism Initiative – a Multicentre Study (EU-AIMS, http://www.eu-aims.eu/), StemBANCC (http://stembancc.org/), the U.S. National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). In the case of NIMH, hundreds of lines have resulted from individual research initiatives focused on technology development, patient phenotyping or genomic analysis; these are being made available on a rolling basis through the NIMH Repository and Genomics Resource (RGR, www.nimhgenetics.org) 17.

The enthusiasm for making large collections of patient-derived hiPSCs is tempered by several hurdles. It remains prohibitively expensive and logistically challenging to make hiPSCs to match the number of subjects needed for statistical power in some of the larger gene association studies of complex brain disorders (e.g., many tens of thousands for SCZ), though automated cell line derivation methods developed by groups such as the New York Stem Cell Foundation 18 may provide a positive step in this direction. This is further dwarfed by the resources required to actually analyze them, where the rate-limiting steps for reprogrammed cell analysis include the lengthy duration of many differentiation protocols, the complexity of the procedures to generate cells of interest and the high cost of reagents such as specialty culture media. Automated methods are currently underway as one means of streamlining the process of analysis 19, though the application of these methods to hiPSC derivatives is currently limited.

Compounding these difficulties for neuropsychiatric disorders is the current symptom-based nosology for disorder classification and the significant overlap in symptoms among many neuropsychiatric disorders, resulting in substantial heterogeneity in the patients from which cell lines are made. While the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework promises to address these shortcomings by focusing on biological and behavioral dimensions rather than diagnoses 20, this remains a work in progress. The disorders most amenable to modeling with cell based methods are those in which the causal abnormality is: [1] highly heritable; [2] genetically simple and highly penetrant; [3] early-onset in development; [4] reducible to the actions of one or a few cell types rather than highly complex systems. None of the neuropsychiatric disorders fulfill all of these criteria, though the relative genetic simplicity of some monogenic ASDs fulfill criteria 1–3 and has made them among the wiser investments for initial investigation. The assumption underlying these most tractable disorder choices is that the number of subject-lines required for obtaining a sufficiently powered study is manageable in comparison with genetically complex disorders for any assay of a given sensitivity and effect size.

Additionally, monogenic disorders are best-suited for analysis of isogenic lines in which a disease-associated risk variant is engineered into a control line or repaired in a patient-derived line. The 2012 workshop recommendation to improve cell engineering and reporter methods has been most successfully addressed with the optimization and widespread adoption of more facile methods of gene editing such as CRISPR/Cas9 21, which permits the analysis of more complex disorders through introduction or rescue of risk variants at multiple loci. In the absence of systematic control of technical variation among cell lines from a single subject, along with the inherent biological variability between subjects, the analysis of isogenic lines differing only in defined loci (e.g., using an inducible conditional approach) remains the best way to validate the mechanistic basis of a difference suggested from case-control comparisons.

The Continuing Importance of Improving Cell and Tissue Differentiation Protocols

hESCs/hiPSCs as a Tool for Functional Genomics

As discussed at the 2012 workshop, any cell-based disease assay requires that the abnormality be [1] intrinsic to and retained in the specific cells being studied; [2] resolved in the assay being used in a robust, reproducible and predictive manner. While predictive value doesn’t equate with pathophysiological causality (e.g., a diagnostic biomarker can be strictly correlative), most efforts have been focused on identifying causal mechanisms and, by extension, therapeutic targets. Relatedly, there is appreciation of the importance of using hiPSCs as a tool for follow-up functional analysis of data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS). A substantial proportion of common variation associated with neuropsychiatric disorder risk is in non-coding regulatory regions of the genome, as was demonstrated for SCZ 22. Thus, a logical next step is to perform transcriptomic and open chromatin analysis on patient post-mortem tissue and patient-derived hiPSCs as a means to identify the causal variants and global unbiased case-control differences in gene expression 23. An important caveat to this approach is the still rudimentary state of most cell differentiation protocols, as important functional genomic signal could be lost in heterogeneous tissue or cultures, while spurious artifacts could be generated from hiPSC derivatives that are not adequately optimized.

Optimizing the Fidelity of hESC/hiPSC-Derived Cell Types

A recent comparative analysis of different sources of human neural progenitor cells (NPCs) illustrated the need for protocol improvements, as monolayer cultured primary human NPCs showed a gene expression profile that was more faithful to that of NPCs in human brain tissue than did hiPSC-derived NPCs 24. In addition to providing a computational approach to standardizing and refining in vitro protocols, this study exemplified the current challenges for hiPSC differentiation protocols in achieving adequate fidelity and maturation to match that seen in the human brain. With the possible exception of midbrain A9 nigral dopaminergic neurons 25 and limb innervating spinal motor neurons 26–29, current protocols do not have adequate control over regional or cell-type identity and maturation. Not coincidentally, the optimization of nigral and motor neuron protocols was preceded by an extensive body of literature regarding the mechanisms controlling fate specification of those cell types; other cell-type differentiation protocols remain a work in progress (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assay improvements and their application to neuropsychiatric disorder research.

| Monolayer-Based Methods, Screens | Organoid, Spheroid, Tissue Chip | Human-Nonhuman Chimera | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology advance * | 41–53, 55–61, 69, 71 | 31, 65, 83–89, 92 | 47, 66, 67, 79–82 |

| Rett syndrome | 97–103, 120 | - | - |

| Fragile X syndrome | 104–112 | - | - |

| Timothy syndrome | 114–116 | - | - |

| PMDS # | 117 | - | - |

| Non-syndromic autism | 120 | 90 | - |

| Schizophrenia | 43, 123–132 | - | - |

| Bipolar disorder | 71, 134–138 | - | - |

includes small molecule and transcription factor-directed differentiation and maturation methods which are mainly utilized in monolayer format; single cell analytic methods are not included in this table as they can be applied to multiple platforms.

PMDS, Phelan McDermid syndrome.

Most protocols typically involve a proof-of-concept using mouse ESCs or iPSCs before moving to human. However, cross-species comparisons have yielded unique features of human brain development that may diverge from those identified in rodents, such as with the spatiotemporal domain of the critical interneuron fate specification factor NKX2-1 in the developing ganglionic eminence 30 and the identification of a human-specific astrocyte gene expression signature 31. Thus, the characterization of phenotypic trajectories of human brain development is important for ensuring that hESC and hiPSC derived neurons and glia cells have phenotypic fidelity to their in vivo human brain counterparts. Human brain reference datasets 32–36, many incorporated into the Brainspan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain (http://www.brainspan.org/) or the Genotype Tissue Expression Project (http://www.gtexportal.org/), are critical resources to provide detailed spatiotemporal maps of gene expression and anatomical data that can be used for both optimizing cell type generation and for generating hypotheses about disease trajectories, including the role of sex differences 37. The PsychENCODE consortium (http://psychencode.org/) goals include the comparison and validation of non-coding genetic element usage between human post-mortem brain and hiPSC derivatives 38. Among its many aims, the BRAIN Initiative Census of Cell Types (RFA-MH-14-215) (http://braininitiative.nih.gov/nih-brain-awards.htm) will provide detailed single cell characterization of individual human cell types in the brain and facilitate the generation of enhancer constructs for marking and purifying hiPSC-derived cell types 39.

As a number of neuropsychiatric disorders are thought to involve cortical imbalances in excitation-inhibition 40, a major focus has been on developing protocols for generating forebrain excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) neurons. The two protocols most commonly used for high efficiency generation of forebrain NPCs (commonly measured by Foxg1+Pax6+Otx2+ co-expression) in monolayer are [1] embryoid body formation with neural rosette selection and [2] dual-SMAD inhibition method, reviewed in 41; glutamatergic neurons appear to be a default differentiation state by these methods, but these are a mixture with respect to cortical laminar identity when such identity is actually measured. Recently, a method was reported for synchronizing differentiation to superficial cortical layer neurons for high throughput compound screening 42, raising confidence that enriched populations of excitatory neuron subtypes can be assayed.

A protocol for making hippocampal dentate granule cells, excitatory neurons produced in vivo by continuous postnatal neurogenesis and implicated in both contextual learning and neuropsychiatric disorders, was developed for hESCs using Wnt3a and BDNF at the embryoid body stage (or alternatively at the post-rosette NPC stage). Validation experiments showed these to have multiple properties consistent with granule neurons 43.

GABAergic neurons are considerably more challenging to generate because of the inherent diversity of GABAergic subtypes in the brain, the requirement for additional instructive steps related to their origin in the ganglionic eminence and evidence of unique trajectories of GABA neuron development in primates versus rodents 44, 45. However, several methods have been developed using factor-induction, reporter lines and FACS-purification to obtain enriched populations of GABAergic interneurons 46–52 and GABAergic medium spiny projection neurons representative of those in the striatum 53. Directed differentiation of parvalbumin versus somatostatin GABA interneuron subtypes have been reported for mouse ESCs 54 but not yet in human.

Directed Fate Choice by Epigenetic Reprogramming

Transcription factor-mediated direct reprogramming methods (e.g., from fibroblast or hiPSC to excitatory neuron, serotonergic neuron, cholinergic neuron, NPC or oligodendrocyte progenitor cell) have made enormous strides, both as a means of bypassing the pluripotent state in somatic cells and by increasing the speed and efficiency of generating cell of interest from pluripotent cells 55–60. More recently, direct conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons has been accomplished with a small molecule cocktail of valproate, CHIR99021, Repsox, forskolin, and inhibitors of JNK, PKC and ROCK 61, albeit with lower efficiency than with transcription factors. A potential disadvantage of this class of methods is the possibility that the direct reprogramming drivers may confound a disease-relevant phenotype (e.g., a neurogenic driver would bypass potentially important NPC phenotypes or neuronal regulatory pathways in which that factor participates). However, the speed and efficiency of generating synaptically active neurons in two-dimensional monolayer culture by this method makes it attractive for scalable assays such as compound library screens.

A modified direct differentiation protocol uses the gene SOX2 alone or with PAX6 to reprogram human or mouse fibroblasts to become induced neural progenitor cells (iNPCs), an intermediate precursor state between hiPSCs and neurons. This is in contrast to protocols using mouse fibroblasts, where other factors such as FOXG1 and BRN2 were utilized to maximize the reprogramming to iNPCs 57. Like iPSCs, iNPCs have the advantage of being a renewable resource; hiNPCs could potentially be grown in bulk and more readily differentiated for brain-related drug discovery or cell therapy purposes.

Approaches to Improve Physiological Maturation of Cells

A major practical barrier to generating cortical neurons and glia is the lengthy time required for differentiation, typically more than 3 months for upper layer cortical neurons and longer for interneurons, astrocytes or oligodendrocytes (reviewed in 62). Full differentiation of neurons does not occur in the absence of astrocytes, which provide signals to promote synaptic maturation and themselves are a key component of the tripartite synapse (pre-synaptic neuron, post-synaptic neuron, astrocyte) 43, 63, 64. As a result, neurons prepared for electrophysiological analysis are typically grown in an astrocyte co-culture. The prevalent use of rodent rather than human astrocytes in co-culture is due to the extended duration of differentiation required for hESC/hiPSC-derived astrocytes.

An important drawback of many current astrocyte differentiation protocols is the tendency to generate cells with flattened, reactive astrocyte features (consistent with a stress response to injury), which will likely confound case-control studies of neuronal homeostasis and synaptic function. NIH initiatives to improve tools for studying glial biology have also solicited improved methods for obtaining and assaying hESC/hiPSC-derived astrocytes (RFA-MH-13-010, RFA-HD-12-211) and a number technical improvements and discovery-based datasets have resulted 36, 65–68. In particular, the use of a serum-free, three dimensional culture protocol generates in vitro astrocytes with the highest fidelity thus far to non-reactive astrocytes in the intact human brain 31, 65. Protocols to generate microglia, a brain cell of non-CNS origin involved in synaptic pruning, are still under development. A parallel direction is improving medium formulation, such as the recently developed ‘BrainPhys basal + serum-free supplements’ medium that facilitates synaptic maturation and supports excitatory and inhibitory activity far better than the currently used DMEM/F12 or Neurobasal-based media 69.

The immaturity of neurons in most current differentiation protocols presents a challenge in the study of late-onset disorders (e.g., neurodegeneration), prompting efforts to accelerate the ‘aging’ process in vitro through such methods as induced stressors or through forced expression of factors such as progerin 62, 70. The bypassing of the pluripotent state during reprogramming may be a key step in retaining important age and disease state-specific epigenetic features. There is evidence that direct fate conversion of fibroblasts to neurons via transcription factors like Ngn2 and/or small molecules can preserve some age-specific features of tissue; one identified mechanism for this phenomenon is compromised nucleocytoplasmic compartmentalization, mediated in part by the age-dependent down-regulation of RanBP17, a nuclear transport receptor 71.

Single Cell Analysis in Protocol Optimization and Disease Assays

A number of single cell analysis tools embrace heterogeneity in order to resolve distinct phenotypic trajectories and stochastic variation in a population, rather than a trend toward the mean, which can create averaging artifacts 72. One example is the analysis of single cell RNAseq data using Monocle, a computational method that is especially suited to identifying branchpoints in lineage determination as well as intermediate phenotypic states, and so can generate pseudo-temporal fate maps 73. Similar phenotypic landscapes can be analyzed using proteomic data 74. Among the many potential uses of single cell analysis are to optimize cell protocols by measuring the effects of different culture variables on cell phenotypes 75 or to identify changes in phenotypic trajectories due to genetic or environmental factors associated with disease. Automated time lapse image analysis allows patterns of phenotypic change to be resolved even when there is asynchrony in the time course of phenotypic response, since it measures patterns of change in each cell longitudinally 76–78. The automation is currently limited in the number of features that can be measured, but this is compensated by an increase in throughput 19. Further advances in single cell analytic methods have been fostered by the NIH Common Fund Single Cell Analysis Program (SCAP, http://commonfund.nih.gov/Singlecell/index), which has supported both technology development and its application to basic and translational biology questions.

Human-Nonhuman Chimeras

A drawback of reductionist assays like monolayer cultures is that they cannot resolve many critical developmental features and circuit level complexities that are relevant to complex brain disorders. Transplantation paradigms, once used mainly for demonstrating functional recovery in pre-clinical lesion and cell therapy models, are now increasingly used as way to study case-control differences in how hiPSC derivatives function at a systems level. While in previous years the functional integration of hESC and hiPSC neural derivatives into non-human hosts has been inefficient, there have been recent improvements in obtaining functional integration of hESC-derived excitatory and inhibitory neurons into mice 47, 79, 80. In particular, interneuron-fated NPCs appear to show more extensive dispersion in the brain parenchyma upon engraftment than other neuron types, consistent with their migratory behavior during development 80. Engraftment of primary human glial progenitors into neonatal wild type mice result in the competitive replacement of host astrocytes with those of the donor, resulting in a mouse brain where essentially all astrocytes are of human origin 66–68. The functional measures assayed in these mice could potentially be applied to quantifying higher order case-control differences.

This group also found that the same glial progenitors would preferentially generate oligodendrocytes only when grafted into a non-myelinated host 81. While these results need to be replicated with hiPSC-derived glial progenitors, this interesting feature provides a second paradigm for looking at glial contributions to a disease phenotype. A recent demonstration of optogenetic manipulation of engrafted hESC-derived dopaminergic neurons, while focused on functional recovery in a Parkinson’s disease model 82, provides a proof of concept that the circuit and behavioral consequences of integrated derivatives from control and patient hiPSCs can be precisely controlled. However, these methods are technically difficult and time consuming, such that only a limited number of laboratories have the expertise and resources to perform them (Table 1). While these paradigms are important for establishing construct validity of a disease relevant paradigm, widespread adoption will require that the methods become greatly streamlined.

Microphysiological Systems (MPS): Organoids and Tissue Chips

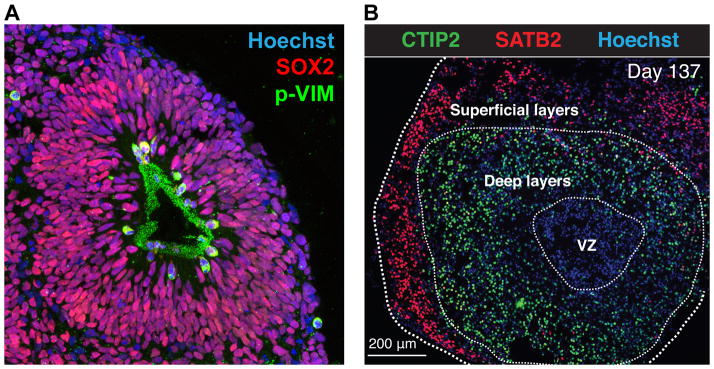

Alternative paradigms that embrace cell heterogeneity in the service of more physiologically relevant organization include microphysiological systems (MPS), which are human-only three dimensional culture systems. One version is a non-adherent suspension culture variously called SFEBq, organoid or spheroid culture (Table 1 and Figure 1). It was first developed by the Sasai laboratory 83 and further adapted by his and other labs 65, 84–89. The procedure typically involves embryoid body formation followed by disaggregation and reaggregation, which yields a suspended three dimensional structure that approximates aspects of in vivo brain organization. The most consistent features to date are distinct proliferative and post-mitotic mantle zones surrounding a ‘ventricular’ lumen, with evidence of layer-specific neuron identities within the mantle zone that suggest a cortical structure. Neuronal subtypes (e.g., GABA) consistent with subcortical structures have also been reported in organoids. Protocol optimization has yielded organoids with reported differences in proliferation rate from patients with microcephaly and migration in patients with macrocephaly, when compared with controls 86, 90. Furthermore, directed differentiation of cortical spheroids has yielded more consistent laminar organization, physiologically relevant neuron-astrocyte morphology and evidence of spontaneous network activity in these structures 65. A future growth area may be improving the maturation state of organoids and enhancing self-organization of non-cortical regions, such that long distance connectivity (e.g., thalamocortical) and emergence of complex circuit activity can be measured. Additionally, organoids/spheroids could be adapted to high throughput screening provided appropriate reporters or readouts can be incorporated. Importantly, there is a continuing need for improvement in reproducibility of organoid size, shape and organization.

Figure 1. Example of a complex cell-based assay to study complex brain disorders.

In vitro-grown human cortical spheroids viewed in cross-section. (A) Organization of a proliferative zone inside a spheroid, where all NPCs are recognized by an anti-SOX2 antibody (red) and those dividing NPCs are shown in green by the expression of the radial glia-specific mitotic marker phospho-vimentin (p-VIM). (B) Spheroids after 137 days of differentiation and staining with anti-CTIP2 and anti-SATB2 antibodies, indicative of layer-specific neurons, and Hoechst dye, marking nuclei. Used with permission from Sergiu Pasca, unpublished data and 65.

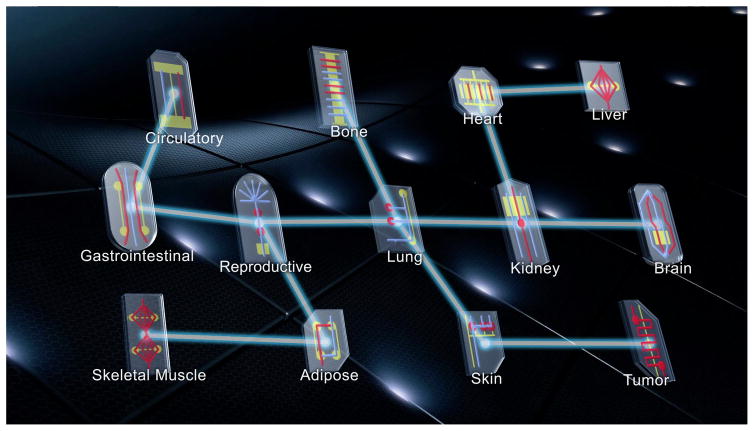

A related MPS technology is the tissue chip, which is a multicellular structure that mimics minimal units of organ function and is embedded in a non-living microfluidic platform that allows both efficient exposure to test compounds and efficient physiological readout. The NIH Common Fund Tissue Chip Program, established in 2011, is a collaboration with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to design modular tissue chips representing the function of multiple organs and ultimately to integrate them into a platform that allows pre-clinical pharmacokinetic and toxicological testing of candidate compounds (Figure 2 and 91). Among the tissue chips are those representing the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and vascularized neural tissue. As recently reported, the group developing the neural tissue chip had successfully created a structure consisting of neurons, astrocytes, microglia and rudimentary vascular structures made of endothelial cells and pericytes. The chip was used to measure the transcriptional response to 60 training compounds and a machine learning paradigm was applied to accurately classify 9 of 10 additional compounds as toxic or non-toxic 92. As noted in the report, these neural structures are still at an early maturational stage and do not have a functional BBB or evidence of synaptic/circuit activity, which are limitations in the chip’s utility in its present state. However, these findings are an important milestone in the development of reagents for testing the effect of compounds in a biomimetic human brain-like structure. In principle, a chip sufficiently validated for pathophysiological relevance could also be used to study compound efficacy in a ‘virtual phase II clinical trial’ performed entirely in vitro.

Figure 2. Integrating tissue chips into a multi-organ system for toxicology and efficacy studies.

The basic paradigm involves mimicking minimal units of organ function, using biocompatible matrices that allow introduced cells to organize in ways that closely approximate organ structures in vivo (e.g., intestinal crypt, kidney proximal tubule, blood brain barrier, neural circuit). A modular design and connectivity via a microfluidic platform (ideally approximating a circulatory system) allow tissue chips to be integrated into a system that allows compound pharmacokinetics to be measured, as well as toxicity and efficacy (if an adequate disease-relevant assay is incorporated). Used with permission from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Latest Findings in Cell-Based Analysis of Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorder Overview

Where the 2012 workshop provided some early hints at cell-based phenotypes from patient-control comparisons of ASDs, recent progress has shown some phenotypic commonalities emerging, albeit in studies with small sample sizes. ASDs are characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication, restricted interests and repetitive behavior, emerging within the first few years after birth and varying in severity. The genetics of most cases are complex and likely involve a combination of inherited and/or de novo mutations 93. However, a sizable number of syndromic ASDs associated with highly penetrant variants in single genetic loci include Rett (Mecp2 loss of function mutations), Fragile X (CGG repeat expansion in Fmr1 gene), Timothy (CACNA1C missense mutation) and Phelan McDermid (varying sized deletions in the 22q13 chromosomal locus) syndromes, and it is here where some of the most intensive initial cell-based research into complex brain disorders has been performed. While there remains an incomplete understanding of the cell types and circuit dynamics involved with these disorders, there is evidence that ASDs involve excitatory-inhibitory imbalances 94, 95 and functional hyperconnectivity during childhood, particularly in the cortex 96.

Rett Syndrome (RTT)

Analysis of hiPSC lines from subjects with RTT, or hESCs with engineered Mecp2 loss of function mutations, showed that derived neurons (primarily cortical glutamatergic neurons were tested) have reproducibly decreased cell soma and nucleus size, neurite complexity 97–99, spine density and synapse number 100, dysfunction in action potential generation, voltage-gated Na+ currents, and miniature excitatory synaptic current frequency and amplitude 98. Additionally, the loss of Mecp2 in hESCs leads to a global decrease in transcription and Akt-mediated translation, along with mitochondrial dysfunction 99. Interestingly, some of these defects were rescued by treatment with insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) in a manner similar to that seen in Mecp2 mutant mice 100–102, which is consistent with a role for IGF1 in cell growth; this IGF1 rescue has since been identified for other hiPSC and mouse-based assays for ASDs (see below). In contrast, duplication of the Mecp2 locus yields neurons with increased synaptogenesis, dendritic complexity and synchronized burst activity, which could be returned to control levels by treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors 103.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS)

This disorder is due to a CGG repeat expansion in the 5′-untranslated region of the FMR1 gene, which leads to hypermethylation and transcriptional silencing of the gene encoding the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) 104. FMRP functions to broadly repress translation, including in the context of activity-dependent neural plasticity. Comparison of human pluripotent cells have shown that, while hESCs express FMRP and are silenced only upon differentiation, hiPSCs tend to retain or even produce a silenced locus where there is a FMR1 CGG repeat expansion, 104–106. The mechanisms underlying this difference are unclear and may vary from line to line, making it difficult to characterize the developmental trajectory of the deficits with certainty. Studies have shown that fibroblasts from FXS patients are often mosaic with differing levels of CGG repeat length per cell 107, 108, which allows comparison of quasi-‘isogenic’ lines from the same subject. Similar to Rett syndrome, FXS hiPSC-derived neurons show deficits in neurite complexity compared to controls 107. While a detailed cellular phenotyping of FXS neurons remains to be reported, expression profiling shows that these neurons (generated by dual-Smad inhibition) are down-regulated in genes involved in neuronal differentiation and axon guidance compared to controls. In particular, loss and gain-of-function experiments supported a model whereby FMRP promotes neuronal maturation in part through the microRNA hsa-mir-383 mediated repression of REST, which itself is a global repressor of the neuronal differentiation program 109.

In spite of the challenges in characterizing the phenotype of FXS patient-derived cells, the nature of the genetic defect provides at least one straightforward readout for high throughput compound screening, which is Fmr1 expression levels 110. Two recent reports highlight the use of this readout. In one, a team from Novartis optimized a platform for high-content and -throughput analysis of FMRP re-expression in response to 50,000 compounds, obtaining a hit rate of 1.1–2.8% of 790 compounds selected for dose-response assays in hiPSC-derived NPCs 111. Another team from NIH developed a platform using novel anti-FMRP antibodies with time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (trFRET) detection in a 1,536 well plate format; using this to screen a 5,000 compound collection, they identified 6 compounds that yielded a small increase in FMR1 expression in FXS patient hiPSC-derived NPCs 112. While neither study identified a compound with strong expression-inducing activity, the reports provide a proof-of-concept that such straightforward assays for FXS are possible.

Timothy syndrome (TS)

This disorder is caused by a missense mutation in the CACNA1C gene, encoding the L-type calcium channel Cav1.2, which prevents voltage-dependent channel inactivation and leads to increased calcium permeability. This gain-of-function mutation is highly penetrant for autism; interestingly, polymorphisms of the CACNA1C gene have been associated more generally with ASDs, SCZ and BPD 22, 113. Initial analysis of hiPSC-derived neurons from two TS patients and two controls found evidence of cortical laminar fate changes, suggesting increased numbers of subcortical projection neurons at the expense of callosal projection neurons 114. Follow-up analysis showed that the mutated Cav1.2 channel resulted in activity-dependent retraction of dendrites similarly in rat, mouse and human neurons; interestingly, this did not depend on calcium influx but may involve calcium-independent actions of GTPases, as Rho expression increased in mutant neurons and the dendrite retraction phenotype was blocked by forced over-expression of the Rho-inhibiting GTPase Gem, which acts as one mediator of Cav1.2 responses 115. However, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) on TS-derived NPCs and neurons found a substantial activity-dependent co-regulation of calcium-dependent transcriptional regulators, suggesting that multiple pathways are affected downstream of the mutant Cav1.2 channel, some consistent with differentiation deficits and others involving genes associated with intellectual disability 116.

Phelan McDermid Syndrome (PMDS)

Deletions of varying lengths in the 22q13 locus have been found in subjects with PMDS and these deletions typically include SHANK3, which encodes a post-synaptic density protein and is a strong candidate for the autistic features of the syndrome. Initial analysis of PMDS hiPSC lines indicated reduced SHANK3 expression and a specific defect in excitatory rather than inhibitory transmission, as measured by decreased numbers of synaptic puncta, increased input resistance and decreased frequency and amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). This defect was substantially rescued by forced expression of SHANK3, supporting its causal role in the phenotype, and was partially rescued with treatment with IGF1 117. This supported analogous studies showing a rescue of phenotypic deficits by IGF1 in rodents with Shank3 mutation 118. Indeed, the ability of IGF1 to rescue phenotypes in multiple ASDs suggests at least one common mechanism underlying these syndromes 119, though the possibility remains that the pro-growth actions of IGF1 are epiphenomenal to the causal mechanisms of the defect.

Non-syndromic and idiopathic autism

While forms of autism associated with highly penetrant single gene variants are referred to as syndromic (because autism is usually only one of several clinical features), a non-syndromic form of autism was linked to de novo translocations involving the gene for TRPC6, a voltage-independent, calcium-permeable cation channel associated with dendritic spine growth and synaptogenesis. A comparison of mutant mice and a patient hiPSC-derived mixed GABA and glutamate neuronal assay showed a reduction in dendritic arborization and spine density selectively in glutamatergic neurons, consistent with its preferential expression in these neurons; this phenotype could be reproduced by TRPC6 knockdown in control lines and in mouse brain. Parallel analysis of RTT hiPSC lines indicated that TRPC6 is a downstream target of Mecp2, suggesting that they act in a common pathway. Finally, analysis of nearly 2000 subjects (autism cases and controls) found an over-representation of TRPC6 in the autism cases, providing evidence that cell-based assays can yield phenotypes for risk variants associated with non-syndromic autism 120.

Recent analysis of hiPSCs from subjects with severe idiopathic autism with macrocephaly, using an organoid assay, found an upregulation of genes involved in cell proliferation, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic assembly. More detailed analysis of the ASD-derived organoids found an accelerated cell cycle and overproduction of GABAergic inhibitory neurons. The transcription factor FOXG1 was found to be overexpressed in NPCs, and knockdown of FOXG1 normalized interneuron numbers to control levels. Based on this, the authors proposed that FOXG1-mediated over-production of interneurons may be an early causal feature in ASD pathophysiology 90. While these results suggesting abnormally high inhibitory contributions may appear at odds with the high incidence of seizures in children with ASDs and evidence of hyper-excitability in non-human experimental paradigms, it highlights the importance of characterizing the developmental trajectory and cell-type, synapse and circuit-level specificity of defects, rather than expecting any assay to represent the totality of a disorder. Furthermore, since each of the aforementioned studies used a small number of patient lines, the results require replication in a larger sample set.

In some cases parallel analysis of hiPSCs alongside genetic mutant mice, or use of a mouse with a human disease variant, can provide independent measures of construct validity. One such example is the substitution of an arginine with cysteine at residue 704 (R704C) in the human neuroligin-4 (NL4) gene that is associated with autism; when introduced into the NL3 gene in mice (used because NL4 is poorly conserved and weakly expressed in mice), the mutation caused decreased AMPA receptor-mediated postsynaptic responses due to due to increased AMPA receptor endocytosis. Further analysis indicated that the mutation generated a non-functional protein that acts as a dominant-negative by enhanced interaction with AMPA receptors. Surprisingly, exogenous expression of the disease-associated human variant NL4 (R704C) caused the opposite effect in enhancing AMPA receptor mediated responses; analysis of the wild type NL4 suggests it may normally act as a dominant-negative by decreasing excitatory responses, such that the disease-associated R704C mutation actually allows excitatory responses to occur. This work implies that different NL proteins have unique functions and that misregulated expression of NL4 specifically may have a pathogenic effect by enhancing excitation 121. Further work is required to characterize this mechanism and determine if it works similarly in hiPSC-derived neurons.

Schizophrenia

SCZ affects approximately 1% of the population and involves a variety of deficits in cognition including working memory and sensory gating; while it usually manifests in adolescence or early adulthood, onset during childhood can occur and there is strong evidence of atypical developmental trajectories early in life 122. Like ASDs, SCZ is thought to involve excitatory-inhibitory imbalances, though the disease specificity of such imbalances is likely dependent on the kinds of synapses and circuits involved 40. Progress in studying SCZ has been somewhat slower than for ASDs, in large part because there are not yet any highly penetrant single gene variants reproducibly associated with SCZ; genome-wide examination of common variation has thus far identified over 100 loci of common variation associated with SCZ, each of which contribute only minutely to the overall high heritability (~80%). While analysis has been done on idiopathic SCZ patient hiPSC lines, the predominant genomic selection criteria have been based on rare genomic copy number variants of larger effect (e.g., 22q11.2, 15q11.2 deletions 123, 124 and selected rare single gene variants (e.g., DISC1, NRXN1 125, 126).

Biospecimens obtained from a group of four idiopathic SCZ patients have been subjected to analysis in several reports 127–130. Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of hiPSC-derived NPCs showed alterations in expression modules for cytoskeletal remodeling, oxidative stress 128, along with WNT pathway gene expression enrichment and signaling elevation 130, which were validated in follow-up tests showing migratory and oxidative stress defects 128. Mixed neuronal cultures generated from both control and SCZ hiPSCs showed activity-dependent release of multiple catecholamine and neuropeptide neurotransmitters which, along with numbers of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-expressing neurons, were higher in SCZ; it was unclear whether this reflected differential survival, stress response or some other mechanism 129. Based on evidence suggesting that SCZ involves perturbations in hippocampal neurogenesis, the dentate gyrus neuron differentiation protocol was used to analyze idiopathic SCZ versus control hiPSC lines. Results showed decreased granule neurogenesis and, in those dentate granule neurons that were generated, a decreased spontaneous neurotransmitter release compared to controls, reflected in decreased frequency and amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic currents 43. An analysis of a different set of patients showed diminished mitochondrial function in hiPSC-derived glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurons from two SCZ subjects compared to controls 131. While caution is warranted based on the small sample size, variable clinical assessment and unknown genetics, the results do suggest that dysregulation of oxidative stress response is one feature of the SCZ cellular phenotype.

A detailed analysis of hiPSC-derived NPCs from three childhood onset SCZ patients with microdeletion in the 15q11.2 chromosomal locus showed deficits in adherens junctions and apical polarity in radial glia, the mid-gestation neural stem cells. Among the four genes in the deleted region, CYFIP1 haploinsufficiency was identified as responsible for the phenotype, though dysregulation of the cytoskeletal modulating WAVE complex. By comparison, NPCs from two SCZ patients with DISC1 point mutations did not show these deficits 124, supporting the idea that SCZ can arise through multiple developmental and cellular pathways and/or is heterogeneous in nature.

Different DISC1 variants have been associated with schizoaffective disorders in a Scottish family and in an American cohort, though the strength of the association is hotly debated. The same DISC1 variant patient hiPSC lines studied in Yoon 124 were compared with engineered isogenic hiPSC lines (i.e., DISC1 mutation edited into control lines or DISC1 mutation corrected in a patient line) and analyzed via differentiation into predominantly (90%) forebrain glutamatergic neurons. While no obvious persistent differences in NPC or cortical laminar identity were observed, neurons from SCZ showed presynaptic transmission deficits, including depolarization-induced vesicle release compared to controls. Furthermore, transcriptomic analysis showed changes in gene modules for neural development, synaptic transmission and DISC1 interacting proteins 125. By comparison, analysis of isogenic hiPSC lines where a DISC1 truncation was engineered near the site of the balanced translocation found in a Scottish pedigree found a similar pattern of transcriptomic dysregulation but did not find evidence of pre-synaptic neuronal deficits. Instead, increased WNT signaling in both NPCs and neurons was observed and accompanied by decreased numbers of Tbr2-expressing cells, suggesting a subtle delay in early phases of neuronal differentiation. It was noted that the phenotypic differences may have been due to technical differences in the neural differentiation protocols or to functional differences in the DISC1 variants being studied 132.

Mutations in NRXN1 have been strongly associated with both autism and SCZ, prompting an analysis of hESCs with different engineered heterozygous mutations in NRXN1; Ngn2-induced neurons derived from these mutant hESCs showed a decreased initial probability of neurotransmitter release, but not the size of the readily releasable pool; the authors interpreted this pre-synaptic impairment as consistent with dysfunctional calcium influx during action potentials 126. While there are differences in the differentiation protocols and the details of the phenotypes reported, the finding of a presynaptic deficit in glutamatergic neurons based on three different paradigm selection criteria (idiopathic SCZ, DISC1 variant and SCZ, NRXN1 variants in isogenic hESC background 43, 125, 126) suggests this methodology can identify mechanisms contributing to shared pathophysiology. As with ASD studies, reported sample sizes are small and require extensive replication to ensure the robustness of the results.

Bipolar Disorder

Formerly known as Manic-Depressive disorder, BPD is characterized by severe, extended and alternating periods of elevated and depressed mood, energy and activity. BPD is highly heritable and shares a number of genomic risk loci with SCZ and ASDs, although the contribution of any individual locus to overall risk is low 133. The responsiveness of patients to lithium (among the most common first line drug interventions for BPD) remains the most common way to stratify patient populations for analysis. To date, only a limited number of studies are underway to investigate hiPSC-derived phenotypes for BPD.

Analysis of hiPSC-derived and FACS-purified NPCs from two BPD-affected brothers and their unaffected parents showed that BPD NPCs exhibited decreased proliferation and gene expression changes associated with lineage specification, neuronal maturation and calcium ion conductance. Application of CHIR-99021 to inhibit glycogen synthase kinase 3, itself an endogenous inhibitor of WNT signaling, rescued the proliferation defect in the BPD NPCs 134. This lends support to lithium’s activation of WNT signaling as a potential therapeutic mechanism of action for BPD. In a similar vein, a WNT/beta-catenin reporter system was developed and tested for high throughput screening of hiPSC-derived NPCs, identifying a number of hits out of 1500 test compounds and demonstrating proof-of-principle as a primary screen for novel probes and potential therapeutics 135.

The microRNA miR-34a, known to be down-regulated by the drug lithium, was found to be elevated in both post-mortem brain from BPD patients and in cultured neurons directly induced from fibroblasts or differentiated from hiPSCs obtained from BPD patients, compared to controls; further analysis showed that miR-34a targets two genes with variants associated with BPD, ANK3 and CACNB3, blocking miR-34a enhances dendritic arborization while increasing miR-34a expression limits neuronal differentiation 136.

Analysis of 20 subjects based on homozygosity or heterozygosity for the risk genotype at the locus rs1006737 of CACNA1C, associated with BPD and SCZ, found that homozygosity for the risk genotype correlated with increased CACNA1C expression and voltage gated calcium currents compared to the non-risk controls 137. This is consistent with a separate study showing that lithium pretreatment of mixed hiPSC-derived glutamatergic and GABAergic forebrain neurons from BPD patients resulted in decreased calcium transients compared with controls 138.

As part of the phase III NIH Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN, http://www.pgrn.org/), an international collaborative team reported that hiPSC-derived hippocampal neurons from six patients with type I BPD were hyper-excitable, as measured by higher frequency and amplitude of action potentials, compared with those from four unaffected subjects. Furthermore, BPD-derived neurons showed increased mitochondrial gene expression and membrane potential, factors that may in part contribute to hyper-excitability. Furthermore, this hyper-excitability appeared to be specific to BPD and was not found in neurons from patients with SCZ. Interestingly, lithium treatment could restore normal neuronal function but only in those neurons from BPD patients who also responded well to lithium in a clinical setting 139.

While analysis is still in the early stages and requires characterization of cell-type specificity of actions and replication in larger cohorts, the most common findings thus far are abnormalities in WNT signaling and calcium ion conductance, the latter being consistent with findings in other, non-hiPSC-based cell assays 140. For the large subset of BPD patients who do not respond to lithium as a first line treatment, identification of mechanisms, targets and novel therapeutics remain an important goal. Even for lithium responding patients, hiPSC-based approaches could be used to identify potential drug agents that have a broader safety window than lithium.

Breaking through to mechanism, screening and intervention: examples from Neurodegeneration and ASDs

While the cell-based analysis of neuropsychiatric disorders faces the enormous challenge of deconstructing and reconstructing the complex circuitry and heterogeneity of disease pathophysiology, investigators can take heart in some recent hiPSC research success in neurodegenerative disorders. First, by using well-defined hESC/hiPSC and animal assays, the anti-mycotic miconazole and the steroid clobetasol were found to enhance oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro and in demyelination paradigms 141, suggesting that these drugs or their congeners may be further developed for treating demyelinating disorders. Second, while ALS research appeared disadvantaged by the relatively lower overall heritability of the disorder, progress has been facilitated by clear genetic risk loci and the ability to focus on a causal and well characterized cell type, motor neurons, for which hiPSC differentiation protocols are well-advanced 142–145. Recent analysis of motor neurons from ALS patients with different genomic risk variants consistently identified hyperexcitability due to reduced delayed rectifier potassium channel activity as a defect, which could be corrected by modulating the Kv7.2/3 class of potassium channels 146. In a fortunate convergence, a clinical biomarker of motor hyperexcitability and an FDA-approved drug (ezogabine) for this target were already available, facilitating the initiation of a clinical trial for this new indication 13. This is among the first clinical trials based mainly on data from hiPSCs to make the case for clinical efficacy.

Similar promise has been shown for monogenic ASDs, based on a convergence of animal and hiPSC-based studies, showing that insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) ameliorates phenotypic deficits 101, 117–119. This has led to ongoing clinical trials of IGF1 in subjects with Rett, Fragile X and Phelan McDermid syndromes. While it’s unclear whether any of these trials will be the magic bullet for treatment of these disorders, they raise hope in a potential ‘win’ to spur additional investment by industry in advancing cell-based assays for therapeutics development and help establish a cell-based evidentiary framework for FDA review. Additionally, these suggest that cell-based assays can be used for developing more selective agents with an improved therapeutic index.

Strategic Directions for Accelerating Progress

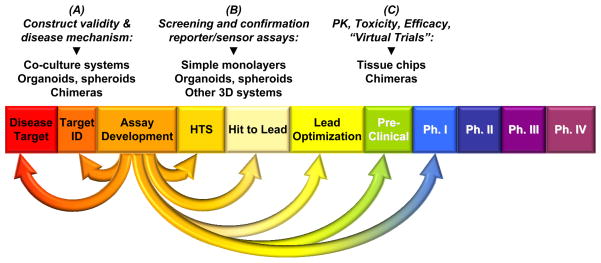

Bringing similar success stories more broadly to neuropsychiatric disorders will require a coordinated effort linking improved hiPSC differentiation protocols and assays with functional genomic analysis of the large number of common and rare risk variants associated with complex brain disorders, in order to integrate the gene networks involved in disease risk with defined cell and circuit phenotypes. These common pathways must likewise be reduced to scalable, fit-for-purpose assays for compound screening and validation (Figure 3). Examples of such scalable assays include those reporting specific signal transduction pathways (e.g., WNT signaling 135), cell differentiation states (e.g., superficial layer cortical neurons 42, oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination 141, 147) and synaptic function 148. Such a coordinated effort requires the interdisciplinary and collaborative efforts of investigators in genomics, stem cell and neurobiology, biotechnology and the pharmaceutical industry, as recommended in the 2012 workshop.

Figure 3. Integrating multiple reprogrammed cell-based platforms into the drug discovery pipeline.

The flexibility of cell reprogramming and differentiation protocols allow for a variety of fit-for-purpose assays for different steps in drug development, including (A) understanding disease mechanisms and identifying druggable targets, (B) high throughput screening (HTS) of compounds and follow-up confirmation, or (C) assessment of pharmacokinetics (PK), toxicity and efficacy at the pre-clinical or ‘virtual clinical trial’ phase. The listed assay types are examples and are not meant to be exhaustive.

A major step in this direction came in 2013, when NIMH began an academic-industry partnership initiative, the National Cooperative Reprogrammed Cell Research Groups (NCRCRG) to study Mental Illness, to develop assays that are robust, highly reproducible and predictive for pathophysiology. This was among the first NIH initiatives to make multi-site reproducibility and control of experimental bias a central feature of the research goals, consistent with the increasing recognition of these needs 149. A major part of the effort is in cross-paradigm validation (e.g., comparing results against non-cell-based methods), evaluation of statistical power and replication of promising findings to improve confidence that results meaningfully and causally relate to disease mechanisms. Another major feature is scaling protocols and assays for utility in high-throughput and high-content screening. Biotechnology and pharma involvement is viewed as critical at this stage for industrialization of key elements and for decision-making on a panel of assays best-suited for the drug development pipeline (Figure 3). Two major collaborations have begun thus far from this initiative, with a focus on SCZ and ASDs (funding opportunity announcement PAR-13-225, queried through https://projectreporter.nih.gov/). Relatedly, the EU-AIMS academic-industry partnership integrates a wide variety of assessments of ASD subjects, matched with hiPSC and animal-based assays in order to identify mechanisms and potential therapeutics.

While simple monolayer designs will remain a mainstay for their ease of use (Table 1), efforts in complex assay design including chimeras, organoids and tissue chip design may play important roles throughout the pipeline, for early target identification, initial compound screening and confirmation, as well as for pharmacokinetic characterization and late pre-clinical and early ‘virtual’ clinical trials of candidate therapeutics (Figure 3). An important advantage of such tools is the ability to account for heterogeneity in the relevant patient population, including genetic variation and patient history (e.g., clinical assessments, known drug response) in the design of precision assays. Supporting this goal are efforts to integrate data from a variety of sources, of which there are several ongoing examples like genomic data through the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap), hiPSC cell line data through biorepositories like the NIMH RGR, clinical phenotyping data through the NIMH Data Archive (http://rdocdb.nimh.nih.gov/), and electronic medical records via i2b2/SHRINE (https://www.i2b2.org/work/shrine.html). A major remaining challenge is integrating these data into a seamless federated structure; disease-focused efforts like EU-AIMS are providing a proof of concept for such an integrated approach. This will allow assay developers to make more informed and selective choices about which hiPSC lines to generate for case-control comparisons and more readily identify a precision assay set that is a best fit for representing the patient population. The ultimate bet is that this infrastructure raises the probability of developing a more comprehensive and effective set of treatments for these devastating disorders.

Acknowledgments

Support for and clearance of this manuscript was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health. The author thanks Margaret Grabb, Douglas Meinecke and Lois Winsky at NIMH and Kristen Fabre at NCATS for thoughtful advice and Sergiu Pasca for the use of primary data images. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Author’s contribution(s): David M. Panchision: manuscript writing, final approval of the manuscript

Disclosure: The author indicates no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trist DG, Cohen A, Bye A. Clinical pharmacology in neuroscience drug discovery: quo vadis? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;14:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyman SE. Revitalizing psychiatric therapeutics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:220–229. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizzo SJ, Edgerton JR, Hughes ZA, et al. Future viable models of psychiatry drug discovery in pharma. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18:509–521. doi: 10.1177/1087057113475871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pankevich DE, Altevogt BM, Dunlop J, et al. Improving and accelerating drug development for nervous system disorders. Neuron. 2014;84:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panchision DM. Meeting report: using stem cells for biological and therapeutics discovery in mental illness, April 2012. Stem cells translational medicine. 2013;2:217–222. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Insel TR. From animal models to model animals. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1337–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeish J, Gardner JP, Wainger BJ, et al. From Dish to Bedside: Lessons Learned While Translating Findings from a Stem Cell Model of Disease to a Clinical Trial. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-David U, Nissenbaum J, Benvenisty N. New balance in pluripotency: reprogramming with lineage specifiers. Cell. 2013;153:939–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissbein U, Benvenisty N. rsPSCs: A new type of pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res. 2015;25:889–890. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alateeq S, Fortuna PR, Wolvetang E. Advances in reprogramming to pluripotency. Current stem cell research & therapy. 2015;10:193–207. doi: 10.2174/1574888x10666150220154820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soares FA, Sheldon M, Rao M, et al. International coordination of large-scale human induced pluripotent stem cell initiatives: Wellcome Trust and ISSCR workshops white paper. Stem cell reports. 2014;3:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paull D, Sevilla A, Zhou H, et al. Automated, high-throughput derivation, characterization and differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Methods. 2015;12:885–892. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkbeiner S, Frumkin M, Kassner PD. Cell-based screening: extracting meaning from complex data. Neuron. 2015;86:160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC medicine. 2013;11:126. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Zhang F. High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nature reviews Genetics. 2015;16:299–311. doi: 10.1038/nrg3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roussos P, Mitchell AC, Voloudakis G, et al. A role for noncoding variation in schizophrenia. Cell reports. 2014;9:1417–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan J. Path from schizophrenia genomics to biology: gene regulation and perturbation in neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells and genome editing. Neuroscience bulletin. 2015;31:113–127. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein JL, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Tian Y, et al. A quantitative framework to evaluate modeling of cortical development by neural stem cells. Neuron. 2014;83:69–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arenas E, Denham M, Villaescusa JC. How to make a midbrain dopaminergic neuron. Development. 2015;142:1918–1936. doi: 10.1242/dev.097394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stockmann M, Linta L, Fohr KJ, et al. Developmental and functional nature of human iPSC derived motoneurons. Stem Cell Rev. 2013;9:475–492. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demestre M, Orth M, Fohr KJ, et al. Formation and characterisation of neuromuscular junctions between hiPSC derived motoneurons and myotubes. Stem Cell Res. 2015;15:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams KL, Rousso DL, Umbach JA, et al. Foxp1-mediated programming of limb-innervating motor neurons from mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6778. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amoroso MW, Croft GF, Williams DJ, et al. Accelerated high-yield generation of limb-innervating motor neurons from human stem cells. J Neurosci. 2013;33:574–586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0906-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onorati M, Castiglioni V, Biasci D, et al. Molecular and functional definition of the developing human striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1804–1815. doi: 10.1038/nn.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang HJ, Kawasawa YI, Cheng F, et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature. 2011;478:483–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller JA, Ding SL, Sunkin SM, et al. Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain. Nature. 2014;508:199–206. doi: 10.1038/nature13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pletikos M, Sousa AM, Sedmak G, et al. Temporal specification and bilaterality of human neocortical topographic gene expression. Neuron. 2014;81:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tebbenkamp AT, Willsey AJ, State MW, et al. The developmental transcriptome of the human brain: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Current opinion in neurology. 2014;27:149–156. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darmanis S, Sloan SA, Zhang Y, et al. A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:7285–7290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507125112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trabzuni D, Ramasamy A, Imran S, et al. Widespread sex differences in gene expression and splicing in the adult human brain. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2771. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akbarian S, Liu C, Knowles JA, et al. The PsychENCODE project. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1707–1712. doi: 10.1038/nn.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YJ, Vogt D, Wang Y, et al. Use of “MGE enhancers” for labeling and selection of embryonic stem cell-derived medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) progenitors and neurons. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao R, Penzes P. Common mechanisms of excitatory and inhibitory imbalance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Current molecular medicine. 2015;15:146–167. doi: 10.2174/1566524015666150303003028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DS, Ross PJ, Zaslavsky K, et al. Optimizing neuronal differentiation from induced pluripotent stem cells to model ASD. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2014;8:109. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boissart C, Poulet A, Georges P, et al. Differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells of cortical neurons of the superficial layers amenable to psychiatric disease modeling and high-throughput drug screening. Translational psychiatry. 2013;3:e294. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu DX, Di Giorgio FP, Yao J, et al. Modeling hippocampal neurogenesis using human pluripotent stem cells. Stem cell reports. 2014;2:295–310. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sultan KT, Brown KN, Shi SH. Production and organization of neocortical interneurons. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2013;7:221. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petanjek Z, Dujmovic A, Kostovic I, et al. Distinct origin of GABA-ergic neurons in forebrain of man, nonhuman primates and lower mammals. Collegium antropologicum. 2008;32(Suppl 1):9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maroof AM, Keros S, Tyson JA, et al. Directed differentiation and functional maturation of cortical interneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicholas CR, Chen J, Tang Y, et al. Functional maturation of hPSC-derived forebrain interneurons requires an extended timeline and mimics human neural development. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeRosa BA, Belle KC, Thomas BJ, et al. hVGAT-mCherry: A novel molecular tool for analysis of GABAergic neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2015;68:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim TG, Yao R, Monnell T, et al. Efficient specification of interneurons from human pluripotent stem cells by dorsoventral and rostrocaudal modulation. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1789–1804. doi: 10.1002/stem.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham M, Cho JH, Leung A, et al. hPSC-derived maturing GABAergic interneurons ameliorate seizures and abnormal behavior in epileptic mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:559–573. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Liu H, Sauvey C, et al. Directed differentiation of forebrain GABA interneurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1670–1679. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nestor MW, Jacob S, Sun B, et al. Characterization of a subpopulation of developing cortical interneurons from human iPSCs within serum-free embryoid bodies. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;308:C209–219. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00263.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delli Carri A, Onorati M, Lelos MJ, et al. Developmentally coordinated extrinsic signals drive human pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward authentic DARPP-32+ medium-sized spiny neurons. Development. 2013;140:301–312. doi: 10.1242/dev.084608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyson JA, Goldberg EM, Maroof AM, et al. Duration of culture and sonic hedgehog signaling differentially specify PV versus SST cortical interneuron fates from embryonic stem cells. Development. 2015;142:1267–1278. doi: 10.1242/dev.111526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ang CE, Wernig M. Induced neuronal reprogramming. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:2877–2886. doi: 10.1002/cne.23620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J, Pol SU, Haberman AK, et al. Transcription factor induction of human oligodendrocyte progenitor fate and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2885–2894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408295111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maucksch C, Jones KS, Connor B. Concise review: the involvement of SOX2 in direct reprogramming of induced neural stem/precursor cells. Stem cells translational medicine. 2013;2:579–583. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Z, Jiang H, Zhong P, et al. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to induced serotonergic neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.101. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu ML, Zang T, Zou Y, et al. Small molecules enable neurogenin 2 to efficiently convert human fibroblasts into cholinergic neurons. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2183. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ladewig J, Mertens J, Kesavan J, et al. Small molecules enable highly efficient neuronal conversion of human fibroblasts. Nat Methods. 2012;9:575–578. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu W, Qiu B, Guan W, et al. Direct Conversion of Normal and Alzheimer’s Disease Human Fibroblasts into Neuronal Cells by Small Molecules. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Studer L, Vera E, Cornacchia D. Programming and Reprogramming Cellular Age in the Era of Induced Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang X, Zhou L, Wagner AM, et al. Astroglial cells regulate the developmental timeline of human neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11:743–757. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halassa MM, Haydon PG. Integrated brain circuits: astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:335–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pasca AM, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, et al. Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods. 2015;12:671–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han X, Chen M, Wang F, et al. Forebrain engraftment by human glial progenitor cells enhances synaptic plasticity and learning in adult mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen H, Qian K, Chen W, et al. Human-derived neural progenitors functionally replace astrocytes in adult mice. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1033–1042. doi: 10.1172/JCI69097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Windrem MS, Schanz SJ, Morrow C, et al. A competitive advantage by neonatally engrafted human glial progenitors yields mice whose brains are chimeric for human glia. J Neurosci. 2014;34:16153–16161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1510-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bardy C, van den Hurk M, Eames T, et al. Neuronal medium that supports basic synaptic functions and activity of human neurons in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E2725–2734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller JD, Ganat YM, Kishinevsky S, et al. Human iPSC-based modeling of late-onset disease via progerin-induced aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mertens J, Paquola AC, Ku M, et al. Directly Reprogrammed Human Neurons Retain Aging-Associated Transcriptomic Signatures and Reveal Age-Related Nucleocytoplasmic Defects. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:705–718. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]