Abstract

Inbreeding depression refers to lower fitness among offspring of genetic relatives (1). This reduced fitness is caused by the inheritance of two identical chromosomal segments (autozygosity) across the genome, which may expose the effects of (partially) recessive deleterious mutations. Even among outbred populations, autozygosity can occur to varying degrees due to cryptic relatedness between parents (2). Using dense genome-wide SNP data, we examined the degree to which autozygosity associated with measured cognitive ability in an unselected sample of 4,854 participants of European ancestry. We used runs of homozygosity—multiple homozygous SNPs in a row— to estimate autozygous tracts across the genome. We found that increased levels of autozygosity predicted lower general cognitive ability, and estimate a drop of 0.6 standard deviations among the offspring of first cousins (p = 0.003 - 0.02 depending on the model). This effect came predominantly from long and rare autozygous tracts, which theory predicts as more likely to be deleterious than short and common tracts. Association mapping of autozygous tracts did not reveal any specific regions that were predictive beyond chance after correcting for multiple testing genome-wide. The observed effect size is consistent with studies of cognitive decline among offspring of known consanguineous relationships (3). These findings suggest a role for multiple recessive or partially recessive alleles in general cognitive ability, and that alleles decreasing general cognitive ability have been selected against over evolutionary time.

INTRODUCTION

General cognitive ability, traditionally measured through IQ-type psychometric tests, is a composite measure of cognition across multiple domains (4-6). It reliably predicts many life outcomes, such as health, longevity, social mobility, and occupational success (7-10). Decades of behavioral genetic research on general cognitive ability have shown moderate to high heritability estimates across development (11, 12), (13, 14). Results from GWAS and mixed linear models estimating variance components from SNPs suggest that the genetic variation underlying general cognitive ability is highly polygenic and mostly additive in nature (15-17). Furthermore, family studies have shown that offspring of consanguineous marriages have lower cognitive performance than the general population, supporting a role for inbreeding depression on general cognitive ability (3, 18-22).

The hypothesized cause of inbreeding depression, directional dominance of alleles that affect fitness, is thought to occur because selection acts more efficiently on additive effects than on recessive effects, which tends to bias deleterious effects toward a recessive mode of action (23). Inbreeding increases the probability that recessive/partially recessive deleterious mutations are homozygous by increasing the proportion of the genome that is autozygous (stretches of two homologous chromosomes in the same individual that are identical by descent). It is important to recognize that traits influenced by inbreeding depression are not predicted to have high levels of non-additive genetic variation; if inbreeding depression occurs because of the effects of rare, partially recessive deleterious mutations, most of the genetic variation will be additive (24, 25). While highly inbred individuals are autozygous for a substantial proportion of their genome (e.g. first cousin inbreeding leads to 6.25% average autozygosity genome-wide), autozygosity still occurs in outbred populations, albeit at lower levels, due to shared distant common ancestors between mates of no known relationship. Using high-density SNP arrays, the existence of autozygosity arising from distant inbreeding can be inferred using runs of homozygosity (ROH)—multiple homozygous SNPs in a row (2, 26, 27). To the degree that ROHs accurately measure autozygosity, ROHs capture not only homozygosity at measured SNPs, but also homozygosity at rare, unmeasured variants that exist within ROHs (28, 29). Thus, inbreeding estimates based on SNP-by-SNP excess homozygosity (Fsnp) capture the effects of homozygosity at common variants, while inbreeding estimates based on the proportion of the genome in ROHs (Froh) capture the effects of homozygosity at both common and rare variants.

To date, a number of studies have examined the effect of Froh burden and individual ROH regions on case/control and quantitative phenotypes, with early studies showing mixed results (30), including a non-significant Froh-cognitive ability relationship among individuals of European ancestry (N=2329) (31). Given the low variation in Froh among outbred samples, it is likely that these studies were underpowered (29). Investigations with larger samples have been more successful, finding increased Froh burden associated with schizophrenia (32), height (33), and personality (34). Here, we present an analysis of Froh on general cognitive ability for 4854 individuals of European ancestry from eight samples, including five samples from the COGENT consortium (35). Understanding the contribution of autozygosity to individual differences in general cognitive ability can help elucidate the genetic architecture underlying this important and highly polygenic trait.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic and Sample quality control

Quality control (QC) procedures focused on properties that would be appropriate across a range of genotyping platforms that differed in SNP density. The main goal—analyzing runs of homozygosity to infer autozygosity—differed from the usual goal of finding associations between individuals SNPs and a phenotype, and so the procedures adopted were more stringent than those typically used in genome-wide association studies. Moreover, because so many SNPs (70-75% depending on the sample) were removed due to linkage disequilibrium pruning during ROH detection (see below), we could afford to use more stringent QC procedures, because dropped SNPs were likely to be in strong linkage disequilibrium with other nearby SNPs that were retained.

Table 1 lists the specific genotyping platforms used, with an average LD-pruned SNP density of 229K SNPs (range: 174K – 277K). The specific QC procedures and numbers of individuals or SNPs dropped at each step can be found in Table S4. Most steps are self-explanatory, so only those needing clarification are discussed. Individuals whose self-reported sex was discrepant from their genotypic sex were dropped, as these individuals might represent sample mix-ups. Individuals who self-identified as non-European ancestry were dropped, as both homozygosity and phenotypic measures might differ between ethnicities or across different levels of genetic admixture. We also merged the genotype data with HapMap2 reference samples (36), and removed anyone clearly outside of the European ancestry cluster. Finally, we did not remove individuals with excess genome-wide homozygosity as such individuals are more likely to be inbred and therefore informative for investigating the current hypothesis.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of genotyping SNPs and ROHs across datasets

| Dataset | N | Region | Platform | SNPs passing QC | LD pruned SNPs passing QC | avg Froh * 100 | SD Froh *100 | avg ROH length (kb) | SD ROH length (kb) | avg ROH count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBG | 301 | Colorado, USA | Affymetrix 6.0 | 577090 | 206772 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 1264 | 703 | 7.20 |

| GAIN NE | 357 | Northern Europe | Perlegen 600K | 280995 | 198218 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 1537 | 1875 | 5.50 |

| GAIN UK | 183 | United Kingdom | Perlegen 600K | 242867 | 174013 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 1550 | 1133 | 3.39 |

| GAIN SP | 68 | Spain | Perlegen 600K | 312730 | 174598 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 1522 | 887 | 1.99 |

| MANC | 763 | England | Illumina 610 | 470062 | 250351 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 1312 | 1480 | 9.91 |

| NEWC | 717 | England | Illumina 610 | 466613 | 247990 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 1286 | 1365 | 9.39 |

| LOGOS | 776 | Greece | Illumina OmniExpress | 393770 | 239923 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 1780 | 2982 | 5.92 |

| NCNG | 623 | Norway | Illumina 610 | 373975 | 195130 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 1682 | 1827 | 6.79 |

| ZHH | 175 | New York, USA | Illumina OmniExpress | 548508 | 274325 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 1540 | 1676 | 10.84 |

| TOP | 305 | Norway | Affymetrix 6.0 | 578177 | 237481 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 1273 | 956 | 9.76 |

| RUJ | 586 | Germany | Illumina OmniExpress | 560407 | 277024 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 1297 | 2148 | 10.32 |

| Total | 4854 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.41 | 0.42 | 1421 | 1829 | 8.02 |

Froh is calculated as proportion of an individual's genome captured in ROH.

Runs of Homozygosity (ROHs) calling procedures

ROH were called in PLINK using the --homozyg command (37), which has been found to outperform other programs in accurately identifying autozygous segments (38). The current analysis incorporated the ROH tuning parameters recommended in Howrigan et al. (38). In particular, each dataset was pruned for either moderate LD (removing any SNP with R2 > 0.5 with other SNP in a 50 SNP window) or strong LD (removing any SNP with R2 > 0.9 with other SNP in a 50 SNP window). For moderate LD-pruned SNPs, the minimum SNP length threshold was set to 35, 45, or 50 SNPs. For strong LD-pruned SNPs, the minimum SNP length threshold was set to 65 SNPs. We did not allow for heterozygote SNPs, used a window size equal to the minimum SNP threshold, and allowed for 5% of SNPs to be missing within the window (38). In addition, PLINK's --homozyg-group and --homozyg-match commands were used to find allelically matching ROH that overlapped at least 95% of physical distance of the smaller ROH. We chose the 65 SNP minimum pruned for strong LD, as this parameter setting has been used in previous analyses (32). Primary Froh burden results, however, were similar for all four tuning parameters used (Table S1).

Froh genotype

Genome-wide ROH burden, or Froh, represents the percent of the autosome in ROHs. Froh was derived by summing the total length of autosomal ROHs in an individual and dividing this by the total SNP-mappable autosomal distance (2.77 × 109). The distribution of Froh in the sample is listed in Figure S1. Froh can be affected by population stratification (e.g., if background levels of homozygosity or autozygosity differ across ethnicities), low quality DNA leading to bad SNP calls, and heterozygosity levels that differ depending on, for example, genotype plate, DNA sources, SNP calling algorithm, or sample collection site. We controlled for covariates in two steps – within dataset and across the combined datasets. Within each dataset, we controlled for the first ten principal components generated from an identity-by-state matrix derived from a subset of SNPs (~50,000) within each dataset. We also controlled for age and age-squared within dataset when provided, as age information was not available in four of the eleven studies (Table 2). We used the linear model residuals from within each dataset as our Froh genotype moving forward. Across the combined samples, we controlled for gender, dataset, the percentage of missing calls - which has been shown to track the quality of SNP calls (39), and excess SNP-by-SNP homozygosity (Fsnp, from PLINK's --het command) - which can be used to test the effects of homozygosity at common but not rare variants.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of general cognitive ability, age, and sex across datasets

| Dataset | N | Region | Cognitive ability measures | Mean Age (SD or range) | Male (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBG | 301 | Colorado, USA | WAIS-III: 2 subtests (Ages 16+) WISC-III: 2 subtests (Ages 8-16) |

15.91 (1.53) | 232 (77%) | 69 (23%) |

| GAIN NE | 357 | Northern Europe | WAIS-III: 4 subtests (Ages 16+) WISC-III: 4 subtests (Ages 5-16) |

10.95 (2.57) | 305 (85%) | 52 (15%) |

| GAIN UK | 183 | United Kingdom | WAIS-III: 4 subtests (Ages 16+) WISC-III: 4 subtests (Ages 5-16) |

11.67 (2.83) | 165 (90%) | 18 (10%) |

| GAIN SP | 68 | Spain | WAIS-III: 4 subtests (Ages 16+) WISC-III: 4 subtests (Ages 5-16) |

9.40 (2.53) | 62 (91%) | 6 (9%) |

| MANC | 763 | England | Cattell Culture Fair Test | 64.9 (6.14) | 226 (30%) | 537 (70%) |

| NEWC | 717 | England | Cattell Culture Fair Test | 65.71 (6.10) | 206 (29%) | 511 (71%) |

| LOGOS | 776 | Greece | Cambridge NTAB: 3 subtests N-Back task Wisconsin card sort Stroop Gambling task Wechsler memory scale |

22.13 (18-29) | 776 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| NCNG | 623 | Norway | California Verbal Learning Test-II D-KEFS Color Word interference WAIS-III Matrix Reasoning subscale Multiple choice reaction time task |

NA | 200 (32%) | 423 (68%) |

| ZHH | 175 | New York, USA | MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery | NA | 85 (49%) | 90 (51%) |

| TOP | 305 | Norway | WASI: 4 subtests National Adult Reading Test |

NA | 165 (54%) | 140 (46%) |

| RUJ | 586 | Germany | WAIS-R | NA | 293 (50%) | 293 (50%) |

| Total | 4854 | --- | --- | --- (---) | 2715 (56%) | 2139 (44%) |

Datasets where age information was unavailable were not included in the regression model.

General cognitive ability phenotype

Table 2 lists the sample characteristics and various measures of general cognitive ability employed (additional description in Supplementary information). Measures of general cognitive ability were standardized within each dataset (Figure S2). We controlled for potential confounds in same manner as the Froh genotype, regressing out the first ten principal components, age, and age-squared within each dataset, and dataset, gender, SNP missingness, and Fsnp across the combined dataset.

Froh burden analysis

To test the effect of Froh burden on general cognitive ability, we examined both fixed-effects modeling (i.e. lm() in R) and mixed-effects modeling treating dataset as a random effect (i.e. lmer() from the lme4 package in R). Both analyses showed very consistent results, and we used fixed-effects modeling approach for all analyses hereafter. For our primary analysis, we tested the effects of Froh after controlling for Fsnp as we have done previously (32), not only because this analysis provides information on the importance of rare recessive variants in particular, which are thought to be the primary cause of inbreeding depression (23), but also because controlling for Fsnp can increase power to detect Froh relationships in the presence of genotyping errors (29). We also report the effects of Froh not controlling for Fsnp. In follow up analyses, Froh burden was partitioned into short and long ROH as well as common and uncommon ROH according to median splits of both variables. Due to the variation in SNP density across dataset platforms (ranging from 300k to over 1 million SNPs), median splits for both length and frequency were calculated within each dataset (see Table S2). Across all datasets, 34% of the total length of ROHs was composed of short ROHs and 66% was composed of long ROHs, whereas 38% of the total ROH length was composed of common and 62% was composed of uncommon ROHs.

ROH mapping analysis

To investigate whether specific genomic regions predicted general cognitive ability, we co-opted the rare CNV commands used in PLINK, whereby each ROH segment was tested at the two SNPs defining the start and end position. At each position, all individuals with ROH overlapping the tested SNP were included as ROH carriers. General cognitive ability residuals, after controlling for all covariates, were used as the dependent variable. We restricted ROH mapping to positions where five or more ROHs existed across the sample, and derived statistical significance at each position from one million permutations in PLINK.

To derive a genome-wide significance threshold for multiple testing, we estimated the family-wise error rate directly from permutation. To do so, we ran 1000 permutations on the general cognitive ability phenotype and obtained empirical p-values in the same manner as above. We then extracted the most significant p-value from each permutation, and used the 95th percentile (or 50th most significant p-value among the set) as our genome-wide significance threshold (p = 4e−6). Thus, under the null hypothesis, we had a 5% chance of observing a single genome-wide significant hit.

RESULTS

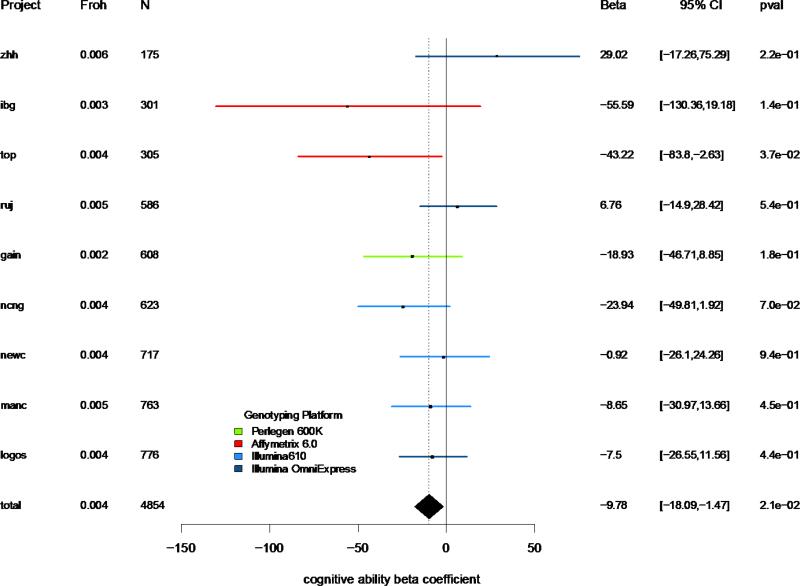

Figure 1 shows the parameter estimates of Froh predicting general cognitive ability within each dataset and combined across the full sample. In the combined sample, higher levels of Froh were associated, albeit modestly, with lower general cognitive ability (β = −9.8, t(4852) = −2.31, p = 0.02). This estimate suggests that every one percentage point increase in Froh corresponds to a ~0.1 standard deviation reduction in general cognitive ability, extrapolating to an expected ~0.6 standard deviation reduction among the offspring of first cousins. Our estimate was not driven by potential outliers in Froh, as it increased when we removed the 33 individuals with no ROH calls and 5 individuals with > 6% Froh (β = −12.8, t(4814) = −2.68, p = 0.007), and was insensitive to ROH calling thresholds ≥ 50 consecutive homozygous SNPs (Figure S3). The relationship between Froh and general cognitive ability remained stable across models where covariates were removed in step-wise fashion or split by age groups or sex. In particular, the estimate for Froh on general cognitive ability was more significant when SNP-by-SNP homozygosity, Fsnp, was removed as a covariate (β = −9.9, t(4852) = −2.92, p = 0.003), whereas Fsnp did not itself predict general cognitive ability (β = −0.1, t(4852) = −0.04, p = 0.97), and suggests that homozygosity at rare variants drove the observed Froh effect. Finally, contrary to a previous report (31), we found no evidence for increased assortative mating or inbreeding at the upper tail of the cognitive ability distribution.

Figure 1. Forest plot of slope estimates and 95% confidence intervals of Froh predicting general cognitive ability.

Points represent slope estimates and bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Datasets are color coded by the genotyping platform used. The three GAIN datasets were combined for clarity.

Additional analyses found that Froh from long ROH (β = −9.2, t(4852) = −2.15, p = 0.03), and rare ROH (β = −15.4, t(4852) = −2.56, p = 0.01) remain significant, whereas Froh estimates from short or common ROH did not (p > 0.30 for both, see Supplementary Information for full analysis). Both short autozygous haplotypes, which arise from more distant common ancestry, and common autozygous haplotypes, which arise from chance pairing of common haplotypes segregating in the population, have had more opportunities to be subject to natural selection when autozygous. This may bias them to be less deleterious when autozygous than long or rare haplotypes.

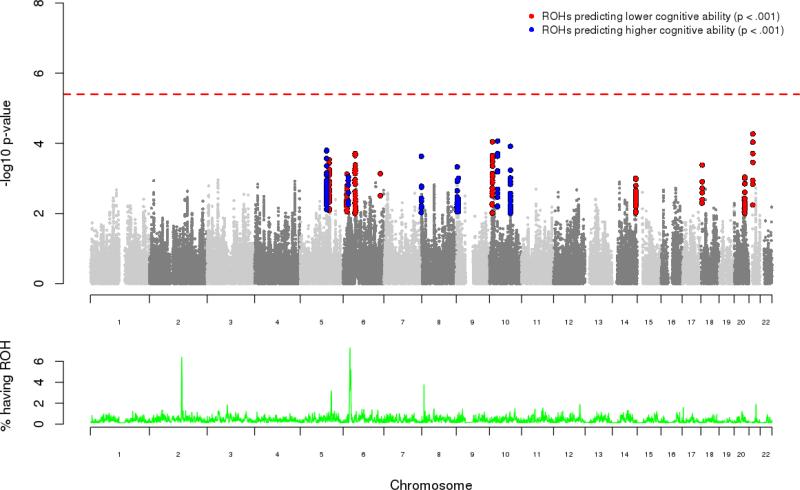

In addition to Froh burden, we mapped individual ROH along the autosome to assess whether specific regions associate with general cognitive ability. Using PLINK, we mapped and analyzed ROH segments at their respective ends (i.e. the first and last SNP in the ROH), counting all overlapping ROH incorporating that SNP as ROH carriers. We observed minimal test statistic inflation across the genome (λGC = 1.02; QQ plot shown in Figure S5), suggesting that the integration of various sub-populations within the full sample were adequately controlled and did not inflate ROH mapping test statistics. Although we did not identify any specific ROH regions that surpassed strict genome-wide correction (Figure 2), we highlight sixteen regions with p < 0.001 as potential areas of interest (Table S3). Our top association, located on chromosome 21q21.1 (p = 5.4e−5, Figure S6), predicts lower general cognitive ability and has a distinct peak over USP25, a ubiquitin specific peptidase gene expressed across a variety tissues types, including brain (40).

Figure 2. ROH mapping manhattan plot predicting general cognitive ability.

Top panel: −log10 p-values for ROH breakpoint regions predicting general cognitive ability. Regions with p-values below 0.001 are flagged for predicting lower cognitive ability (red) and higher cognitive ability (blue). The red dotted line is the genome-wide correction estimate, set at 4e−6, which is the top 5% of minimum p-values observed across 1000 permutations. Bottom panel: ROH frequencies for each region across the autosome, with the highest frequency of ROH due to balancing selection in the MHC (chr6) and recent positive selection in lactase persistence gene region (chr2).

DISCUSSION

After stringent quality control and the application of preferred methods for detecting autozygosity, we observe a significant, albeit modest, trend of autozygosity burden (Froh) lowering cognitive ability among outbred populations of European ancestry. Inbreeding among first cousins leads to an average Froh burden of 6.25%, and corresponds to a predicted drop of 9.19 IQ points in the current study, an effect consistent with previously detected effects from pedigree-based consanguineous inbreeding (3). In addition, we find that long and rare ROH are driving Froh association to general cognitive ability, as the relationship of Froh to general cognitive ability disappear when restricting to either short or common ROH, but remain when considering either long or rare ROH. At the level of individual ROH, however, we do not identify any specific autozygous loci that significantly predicted general cognitive ability after genome-wide correction.

There were several limitations to the current study that were largely a consequence of combining multiple datasets together. First, the operational construct of general cognitive ability differed somewhat between datasets (see Table 2 and Supplementary Information), and statistical power can be lost as a function of the degree of phenotypic heterogeneity in measured cognitive ability across samples. Second, the autozygosity – cognitive ability relationship might be mediated differentially across sites/datasets. For example, analysis of the Netherlands Twin Registry found that increased religiosity was associated with both higher autozygosity and lower rates of major depression in the Netherlands, which if unaccounted for, would have obscured the true relationship between major depression and autozygosity (41). More recent evidence in the same dataset found that increased parental migration mediated the relationship of education attainment to autozygosity (42). Unfortunately, these potential confounds are often unmeasured and were unavailable in the current study. Third, despite following strict QC procedures, the use of different genotyping platforms affects ROH calls across datasets. Although dataset was included as a covariate, such differences add noise and reduce statistical power, and it is impossible to rule out all biases that could arise from such differences between datasets. Finally, we did not measure copy number deletions in our dataset, and hemizygosity due to deletions could be included in the Froh estimates. Previous studies, however, using deletions called from intensity data found that fewer than 0.3% of the total lengths of ROHs in their samples were actually hemizygous, suggesting that deletions had a minimal effect on the present results (2, 32).

Autozygosity is the most direct measure of inbreeding at the genetic level. It can help elucidate the genetic architecture underlying heritable traits like general cognitive ability and provide clues to the evolutionary forces that acted on alleles affecting the trait. Our results suggest that alleles that decrease cognitive ability are more recessive than otherwise expected, and are consistent with the hypothesis that alleles that lead to lower cognitive ability have, on average, been under negative selection ancestrally.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Bruce Walsh, Robin Corley, Ken Krauter, and Brian Browning for their helpful comments and suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding sources

This work has been supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health:

R01 MH079800 and P50 MH080173 to Anil K Malhotra

RC2 MH089964 to Todd Lencz

R01 MH080912 to David C Glahn

K23 MH077807 to Katherine E Burdick

K01 MH085812 and R01 MH100141 to Matthew C Keller

LOGOS

The LOGOS study was supported by the University of Crete Research Funds Account (E.L.K.E.1348)

TOP

The TOP Study Group was supported by the Research Council of Norway grants 213837 and 223273, South-East Norway Health Authority grants 2013-123, and K.G. Jebsen Foundation.

NCNG

The NCNG study was supported by Research Council of Norway grants 154313/V50 and 177458/V50. The NCNG GWAS was financed by grants from the Bergen Research Foundation, the University of Bergen, the Research Council of Norway (FUGE, Psykisk Helse), Helse Vest RHF and Dr Einar Martens Fund.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Bibliography

- 1.Charlesworth D, Willis JH. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nature reviews Genetics. 2009;10(11):783–96. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuillan R, Leutenegger A- L, Abdel-Rahman R, Franklin CS, Pericic M, Barac-Lauc L, et al. Runs of Homozygosity in European Populations. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;83:359–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afzal M. Consequences of Consanguinity on Cognitive Behavior. Behavioral Genetics. 1988;18(5):12. doi: 10.1007/BF01082310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll JB. Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson W, Bouchard TJ, Krueger RF, McGue M, Gottesman II. Just one g: consistent results from three test batteries. Intelligence. 2004;32(1):95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson W, Nijenhuis Jt, Bouchard TJ. Still just 1 g: Consistent results from five test batteries. Intelligence. 2008;36(1):81–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batty GD, Deary IJ, Gottfredson LS. Premorbid (early life) IQ and later mortality risk: Systematic review. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(4):11. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deary IJ, Weiss A, Batty GD. Intelligence and personality as predictors of illness and death: How researchers in differential psychology and chronic disease epidemiology are collaborating to understand and address health inequalities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2010;11:53–79. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottfredson LS, Deary IJ. Intelligence Predicts Health and Longevity, but Why? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strenze T. Intelligence and socio-economic success: a meta-analytic view of longitudinal research. Intelligence. 2007;35:401–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Jarvik LF. Genetics and Intelligence: A Review. Science. 1963;142(3598):3. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3598.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchard TJ, McGue M. Familial Studies of Intelligence: A Review. Science. 1981;212:5. doi: 10.1126/science.7195071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deary IJ, Johnson W, Houlihan LM. Genetic foundations of human intelligence. Human Genetics. 2009;126:18. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deary IJ, Yang J, Davies G, Harris SE, Tenesa A, Liewald D, et al. Genetic contributions to stability and change in intelligence from childhood to old age. Nature. 2012;482(7384):212–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benyamin B, Pourcain BS, Davis OS, Davies G, Hansell NK, Brion M- JA, et al. Childhood intelligence is heritable, highly polygenic and associated with FNBP1L. Molecular Psychiatry. 2014;19:6. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D, et al. Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011:11. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marioni RE, Davies G, Hayward C, Liewald D, Kerr SM, Campbell A, et al. Molecular genetic contributions to socioeconomic status and intelligence. Intelligence. 2014;44:7. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal N, Sinha SN, Jensen AR. Effects of Inbreeding on Raven Matrices. Behavior Genetics. 1984;14(6):7. doi: 10.1007/BF01068128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badaruddoza, Afzal M. Inbreeding depression and intelligence quotient among north Indian children. Behavior Genetics. 1993;23(4):343–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01067435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bashi J. Effects of inbreeding on cognitive performance. Nature. 1977;266:3. doi: 10.1038/266440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton NE. Effect of inbreeding on IQ and mental retardation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 1978;75(8):3906–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodley MA. Inbreeding depression and IQ in a study of 72 countries. Intelligence. 2009;37:268–76. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlesworth D, Willis JH. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:8. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukai T, Cardellino RA, Watanabe TK, Crow JF. The genetic variance for viability and its components in a local population of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1974;78(4):1195–208. doi: 10.1093/genetics/78.4.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houle D, Hoffmaster DK, Assimacopoulos S, Charlesworth B. The genomic mutation rate for fitness in Drosophila. Nature. 1992;359(6390):58–60. doi: 10.1038/359058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nothnagel M, Lu TT, Kayser M, Krawczak M. Genomic and geographic distribution of SNP-defined runs of homozygosity in Europeans. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19(15):2927–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirin M, McQuillan R, Franklin CS, Campbell H, McKeigue PM, Wilson JF. Genomic Runs of Homozygosity Record Population History and Consanguinity. PloS one. 2010;5(11):e13996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carothers AD, Rudan I, Kolcic I, Polasek O, Hayward C, Wright AF, et al. Estimating Human Inbreeding Coefficients: Comparison of Genealogical and Marker Heterozygosity Approaches. Annals of Human Genetics. 2006;70:11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller MC, Visscher PM, Goddard ME. Quantification of Inbreeding Due to Distant Ancestors and Its Detection Using Dense Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Data. Genetics. 2011;189:13. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ku CS, Naidoo N, Teo SM, Pawitan Y. Regions of homozygosity and their impact on complex diseases and traits. Human Genetics. 2011;129:15. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Power RA, Nagoshi C, DeFries JC, Consortium WTCC. Plomin R. Genome-wide estimates of inbreeding in unrelated individuals and their association with cognitive ability. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2014;22:386–90. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller MC, Simonson MA, Ripke S, Neale BM, Gejman PV, Howrigan DP, et al. Runs of Homozygosity Implicate Autozygosity as a Schizophrenia Risk Factor. PLoS genetics. 2012;8(4):e1002656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McQuillan R, Eklund N, Pirastu N, Kuningas M, McEvoy BP, Esko T, et al. Evidence of inbreeding depression on human height. PLoS genetics. 2012;8(7):e1002655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verweij KJH, Yang J, Lahti J, Veijola J, Hintsanen M, Pulkki-Raback L, et al. Maintenance of genetic variation in human personality: testing evolutionary models by estimating heritability due to common causal variants and investigating the effect of distant inbreeding. Evolution; international journal of organic evolution. 2012;66(10):3238–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lencz T, Knowles E, Davies G, Guha S, Liewald DC, Starr JM, et al. Molecular genetic evidence for overlap between general cognitive ability and risk for schizophrenia: a report from the Cognitive Genomics consorTium (COGENT). Molecular psychiatry. 2014;19(2):168–74. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.International HapMap C, Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449(7164):851–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howrigan DP, Simonson MA, Keller MC. Detecting autozygosity through runs of homozygosity: a comparison of three autozygosity detection algorithms. BMC genomics. 2011;12:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurie CC, Doheny KF, Mirel DB, Pugh EW, Bierut LJ, Bhangale T, et al. Quality Control and Quality Assurance in Genotypic Data for Genome-Wide Association Studies. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34:12. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valero R, Marfany G, Gonzalez-Angulo O, Gonzalez-Gonzalez G, Puelles L, Gonzalez-Duarte R. USP25, a Novel Gene Encoding a Deubiqiutinating Enzyme, is Located in the Gene-Poor Region of 21q11.2. Genomics. 1999;62:395–405. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdellaoui A, Hottenga J- J, Xiao X, Scheet P, Ehli EA, Davies GE, et al. Association Between Autozygosity and Major Depression: Stratification Due to Religious Assortment. Behavioral Genetics. 2013;43:13. doi: 10.1007/s10519-013-9610-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdellaoui A, Hottenga J- J, Willemsen G, Bartels M, Beijsterveldt Tv, Ehli EA, et al. Educational attainment influences genetic variation through migration and assortative mating. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.