Abstract

Background/Objectives

Studies have demonstrated conflicting results about the association between anesthesia exposure and subsequent dementia risk. However, prior studies were retrospective, collecting anesthesia exposure after determining dementia status. We used prospectively collected data to evaluate the associations between anesthesia and dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk.

Design

Cohort study

Participants

Community-dwelling members of the Adult Changes in Thought cohort (N=3,988), age 65 or older, and free of dementia at baseline

Measurements

Participants self-reported all prior surgical procedures with general or neuraxial (spinal or epidural) anesthesia at baseline and reported new procedures every two years. We compared people with high-risk surgery with general anesthesia, other surgery with general anesthesia, and other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia exposures to those with no surgery and no anesthesia. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dementia and AD associated with time-varying lifetime and recent (past 5 years) anesthesia exposures.

Results

At baseline, 254 (6%) people reported never having anesthesia; 248 (6%) had ≥1 high-risk surgery with general anesthesia, 3,363 (84%) had ≥1 other surgery with general anesthesia, and 123 (3%) had ≥1 surgery with neuraxial anesthesia. High-risk surgery with general anesthesia was not associated with an increased risk of dementia (HR=0.86, 95%CI=0.58–1.28) or AD (HR=0.95, 95%CI=0.61–1.49) relative to no history of anesthesia. People with any history of other surgery with general anesthesia had a lower risk of dementia (HR=0.63, 95%CI=0.46–0.85) and AD (HR=0.65, 95%CI=0.46–0.93) than people with no history of anesthesia. There was no association between recent anesthesia exposure and dementia or AD.

Conclusion

Anesthesia exposure was not associated with an increased risk of dementia or AD in older adults.

Keywords: anesthesia, surgery, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, older adults

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 9.5 million people over age 65 undergo surgery with anesthesia every year in the U.S.(1) One concerning complication is post-operative cognitive decline (POCD),(2) which may occur in up to 80% of patients following cardiac surgeries and 26% of non-cardiac surgeries.(3) There is a perception that POCD may increase risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Animal and molecular studies support this perception by demonstrating associations between general anesthesia exposure and AD pathogenesis.(4–9) Surgery itself may also contribute to POCD and subsequent dementia or AD risk. High-risk surgery such as cardiac surgery may increase risk of post-operative delirium, although the exact mechanism is unclear.(10, 11)

Human studies of the association between anesthesia and dementia have not consistently confirmed findings from animal models. A meta-analysis of 15 studies found no association between general anesthesia exposure and risk of AD (pooled odds ratio=1.05, 95% CI=0.93, 1.19).(12) However, prior studies have used case-control designs which are prone to limitations including recall bias and the use of non-population-based controls.(2, 12, 13) Furthermore, no studies have been able to evaluate whether the stress of surgery itself was associated with dementia or AD, above and beyond anesthesia exposure. A more recent, high quality case-control study attempted to control biases noted in other studies and found an OR of 0.89 (95%CI=0.73, 1.10).(14) A second population-based case-control study with 5,345 dementia cases and 21,380 matched controls found an increased risk of dementia among people exposed to general anesthesia via endotracheal tube intubation (OR=1.34, 95%CI=1.25–1.44) or intravenous/intramuscular injection (OR=1.28, 95%CI=1.14–1.43).(15)

Using data from the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) cohort, we evaluated associations between anesthesia exposure and incident dementia and AD using prospectively collected data. In addition, we attempted to evaluate the associations with high-risk surgery separately from anesthesia.

METHODS

This study cohort was drawn from members of Group Health (GH), an integrated delivery system in Washington State that provides healthcare and/or health insurance to approximately 600,000 members. Study procedures were approved by GH’s Human Subjects Review Committee; all study participants provided written informed consent.

Study population

The ACT study has been described previously.(16) Briefly, in 1994, the ACT study began enrolling randomly-selected, community-dwelling adults who were members of GH and lived in or near Seattle, Washington. Participants had to be 65 years or older and dementia-free at enrollment. In-person visits occur every two years until the participant dies, develops dementia, or withdraws from ACT. Follow-up is still ongoing as of June 2015.

The analyses for this paper include data collected through September 30, 2012. We limited analyses to people with at least one follow-up visit to ascertain possible incident dementia. Our analytic sample included 3,988 people.

Exposure

Self-reported surgery and anesthesia data were collected via interview at baseline and follow-up study visits. Participants were asked, “Have you had any surgery which involved either a general or spinal anesthetic?” If yes, participants reported detailed information including the type of surgery, age at surgery, and type of anesthetic (general, spinal, or unknown). Study interviewers did not distinguish between neuraxial anesthesia types such as epidural vs. spinal anesthesia; therefore, we refer to all spinal anesthesia as neuraxial. Participants reported all prior procedures at baseline; new procedures since the prior study visit were reported at each follow-up visit. To reduce potential reporting errors by participants, all participant-reported procedures and anesthesia combinations were reviewed by an anesthesiologist (RPP). Any procedure/anesthesia combinations that were highly improbable, such as neuraxial anesthesia for coronary artery bypass grafting, were recoded assuming the reported surgery was accurate and the anesthesia was more prone to error.

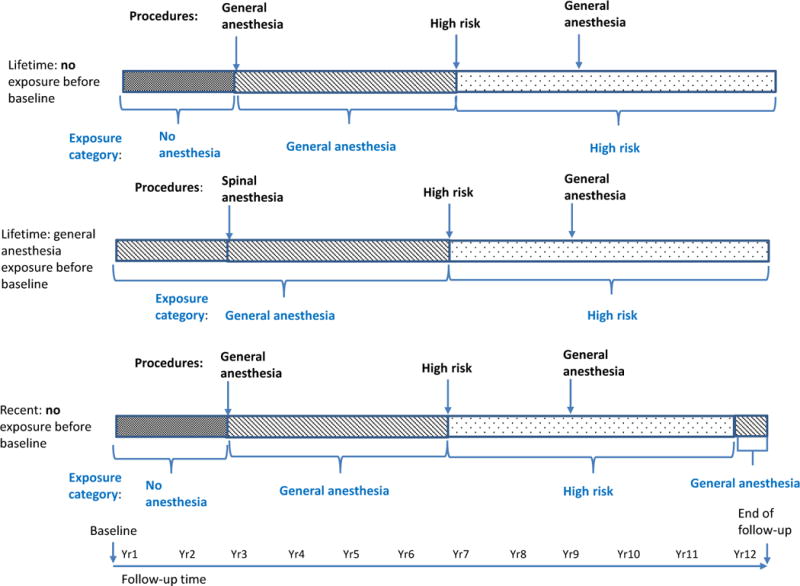

We classified each participant’s lifetime and recent (within the past 5 years) anesthesia exposure (Figure 1). We defined high-risk procedures as those having greater than average risk of mortality or non-fatal myocardial infarction, as determined by an anesthesiologist (RPP). High-risk procedures included skull or brain procedures, cardiovascular procedures, and liver transplants, all of which are performed under general anesthesia. Using a hierarchy to define anesthesia exposure groups, participants with any history of high-risk surgery were classified as “high-risk surgery with general anesthesia.” Participants with no high-risk surgery but any history of other procedures with general anesthesia were classified as “other surgery with general anesthesia.” Participants with only neuraxial anesthesia procedures were classified as “other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia”. Participants with no surgical procedures requiring anesthesia were classified as “no anesthesia”.

Figure 1. Hierarchical classification methods for lifetime and recent anesthesia exposures.

Each of the 3 examples below illustrates the hierarchy we used to classify participants’ lifetime and recent exposures to anesthesia as time-varying exposures.

Figure 1 provides examples of how we classified lifetime and recent anesthesia exposure. Each line represents the time from baseline to end of follow-up. For example, the first bar shows a person who reported no anesthesia exposure before baseline. In year 3, he reported a general anesthesia procedure and had his exposure classified as such. In year 7, he reported a high-risk surgery and had his exposure classified as such. His exposure remained “high-risk surgery” until the end of follow-up, even though he reported a general anesthesia procedure in year 9, because high-risk surgery trumped general surgery in our exposure hierarchy. Similarly, in example 2, the general anesthesia procedure reported before baseline trumped the neuraxial anesthesia procedure reported in year 3; and the general anesthesia procedure was trumped by the high-risk procedure in year 7. In the third example looking at recent anesthesia exposure, exposures only last for 5 years unless they are trumped by another procedure in the hierarchy. So the first general anesthesia procedure exposure defined exposure status for 4 years until it was trumped by a high-risk surgery procedure. The high-risk procedure defined exposure status for 5 years even though another general anesthesia procedure occurred in year 9. Once 5 years had elapsed after the high-risk exposure, the person would be classified as exposed to the prior general anesthesia procedure for 2 more years or until the end of follow-up, whichever came first.

We considered the number of procedures requiring general anesthesia to evaluate any dose-response effect between general anesthesia and risk of incident dementia or AD. For these analyses we combined high-risk and other surgeries with general anesthesia.

Outcomes

Procedures used to identify incident dementia and AD have been described previously.(16) We used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria to define dementia,(17) and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria to define possible or probable AD.(18) We defined the onset dates for dementia and AD as the date midway between the visit that triggered the evaluation leading to a positive diagnosis and the preceding study visit.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics including age, sex, education level, and self-reported race were collected at baseline. Self-reported comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, and Parkinson’s disease), smoking, regular exercise (15 minutes or more at least 3 times per week), self-rated health, and level of difficulty with activities of daily living (walking around the house, getting out of a bed/chair, feeding oneself, dressing oneself, bathing/showering oneself, and getting to or using the toilet) were collected at baseline and each follow-up visit. Depression was assessed at each visit using a modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CESD) scale, and a score of ≥10 represented depression.(19, 20) We calculated body mass index (BMI) from measured height and weight at each study visit. We calculated Charlson comorbidity scores using diagnosis, procedure, and surgical codes in automated data, excluding codes for dementia.(21) We treated all of these characteristics as time-varying in our analyses.

Analysis

We described participants’ demographic and health characteristics by lifetime exposure status at baseline. We conducted three analyses: lifetime exposure, recent exposure (limited to the past 5 years), and lifetime cumulative exposure to general anesthesia (categorized as 0 through 7 or more procedures). We calculated follow-up time (in person-years), and number of dementia and AD outcomes, stratified by exposure status. We used Cox proportional hazards regression with participant age as the time axis to evaluate the associations between each time-varying exposure group and the two outcomes. For each outcome, we calculated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing each anesthesia exposure group to the reference group of “no anesthesia”. Individuals without a dementia diagnosis were censored at their last ACT study visit. For the AD analyses, subjects were censored at the time of dementia diagnosis if they developed dementia of a type other than AD.

All models adjusted for ACT study cohort, baseline age, sex, education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, stroke, coronary heart disease, regular exercise, self-rated health, BMI, depression, Parkinson’s disease, Charlson comorbidity score, and # of activities of daily living that a person had difficulty with. For the recent exposure analyses, we also included a variable in our models indicating whether a person had any history of surgery prior to the 5 year exposure window. We assessed whether proportional hazards assumptions were met by evaluating plots and tests of Schoenfeld residuals; all models had p-values >0.05 suggesting proportional hazards assumptions were met.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we limited the analysis to anesthesia and surgeries reported before age 65 to reduce healthy user bias, which could occur if people with early or impending cognitive impairment were less likely to undergo surgery than those without impairment. We chose age 65 because this was the earliest age someone could enroll in the ACT study, and at time of study entry they were evaluated as cognitively healthy. Second, after noting women were more likely to report a history of anesthesia, we excluded all labor and delivery-related procedures to evaluate whether these procedures overly influenced results. Third, we excluded 22 subjects that had high-risk surgical procedures on the brain because these procedures might be directly related to the risk of developing cognitive dysfunction. All analyses were conducted in Stata/MP 13.1 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Among 3,988 participants, at baseline 248 (6%) had at least one high-risk surgery with general anesthesia, 3,363 (84%) had no history of high-risk surgery but at least one other surgery with general anesthesia, 123 (3%) had only other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia, and 254 (6%) had no history of surgery or anesthesia (Table 1). A lower proportion of people who had other surgery with general anesthesia were male compared with other exposure groups. People who had high-risk surgery with general anesthesia had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease compared with other exposure groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study Participants at Baseline by Surgery and Anesthesia Exposureb

| All subjects | No anesthesia or surgery before study entry | ≥1 high-risk surgery with general anesthesia | ≥1 other surgery with general anesthesia | ≥1 other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | N | %a | |

| Total (row %) | 3,988 | (100) | 254 | (6.4) | 248 | (6.2) | 3363 | (84) | 123 | (3.1) |

| Cohort | ||||||||||

| Original | 2327 | (58) | 129 | (51) | 147 | (59) | 1972 | (59) | 79 | (64) |

| Expansion | 740 | (19) | 68 | (27) | 52 | (21) | 590 | (18) | 30 | (24) |

| Replacement | 921 | (23) | 57 | (22) | 49 | (20) | 801 | (24) | 14 | (11) |

| Age, median (25th, 75th) | 73 (69, 79) | 74 (70, 79) | 74 (70, 78) | 73 (69, 79) | 73 (69, 79) | |||||

| Male | 1621 | (41) | 177 | (70) | 174 | (70) | 1195 | (36) | 75 | (61) |

| At least some college | 2682 | (67) | 176 | (69) | 170 | (69) | 2247 | (69) | 89 | (72) |

| White | 3627 | (91) | 210 | (83) | 226 | (91) | 3088 | (92) | 103 | (84) |

| Hypertension (based on self-report) | ||||||||||

| Treated (yes and current meds) | 1,411 | (35) | 69 | (27) | 118 | (48) | 1192 | (35) | 32 | (26) |

| Untreated (yes but never/past meds) | 209 | (5.2) | 14 | (6) | 18 | (7.3) | 172 | (5.1) | 5 | (4.1) |

| None | 2,333 | (59) | 168 | (66) | 108 | (44) | 1971 | (59) | 86 | (70) |

| Missing | 35 | 3 | 4 | 28 | 0 | |||||

| Diabetes (based on self-report) | 412 | (10) | 27 | (11) | 45 | (18) | 330 | (10) | 10 | (8.1) |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Never | 1926 | (48) | 112 | (45) | 110 | (44) | 1644 | (49) | 60 | (49) |

| Former | 1847 | (46) | 129 | (52) | 128 | (52) | 1536 | (46) | 54 | (44) |

| Current | 207 | (5.2) | 8 | (3.2) | 10 | (4.0) | 180 | (5.4) | 9 | (7.3) |

| Missing | 8 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |||||

| History of stroke (based on self-report) | 126 | (3.2) | 10 | (4.0) | 15 | (6.0) | 100 | (3.0) | 1 | (1) |

| Coronary heart disease (based on self-report) | 715 | (18) | 33 | (13) | 203 | (82) | 456 | (14) | 23 | (19) |

| Body mass index | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 40 | (1.0) | 3 | (1.2) | 2 | (1) | 34 | (1.0) | 1 | (1) |

| Normal | 1247 | (32) | 78 | (32) | 57 | (24) | 1068 | (33) | 44 | (36) |

| Overweight | 1616 | (41) | 106 | (43) | 115 | (48) | 1341 | (41) | 54 | (45) |

| Obese | 997 | (26) | 60 | (24) | 67 | (28) | 848 | (26) | 22 | (18) |

| Missing | 88 | 7 | 7 | 72 | 2 | |||||

| Regular exercise | 1843 | (72) | 184 | (73) | 188 | (76) | 2379 | (71) | 92 | (75) |

| Missing | 10 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |||||

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 599 | (15) | 27 | (11) | 60 | (24) | 499 | (15) | 13 | (11) |

| Missing | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |||||

| Depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression score ≥ 10) | 393 | (10) | 17 | (6.9) | 34 | (14) | 332 | (11) | 10 | (8.3) |

| Missing | 74 | 6 | 5 | 61 | 2 | |||||

| History of Parkinson’s disease | 26 | (1) | 2 | (1) | 3 | (1) | 21 | (1) | 0 | (0) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 2666 | (67) | 182 | (72) | 130 | (52) | 2265 | (68) | 89 | (73) |

| 1 | 680 | (17) | 42 | (17) | 56 | (23) | 567 | (17) | 15 | (12) |

| 2 | 408 | (10) | 22 | (9) | 29 | (12) | 345 | (10) | 12 | (10) |

| 3+ | 212 | (5) | 7 | (3) | 33 | (13) | 166 | (5) | 6 | (5) |

| Number of activities of daily living a person has difficulty withc | ||||||||||

| 0 | 3130 | (79) | 215 | (86) | 203 | (83) | 2612 | (78) | 100 | (82) |

| 1 | 553 | (14) | 25 | (10) | 29 | (12) | 486 | (15) | 13 | (11) |

| 2+ | 285 | (7) | 10 | (4) | 14 | (6) | 252 | (8) | 9 | (8) |

Column percentages based on non-missing data. Missing data is <1% for each covariate except body mass index (2.2%) and depression (1.6%).

Anesthesia/surgery categories are hierarchical and mutually exclusive

Activities of daily living include: walking around the house, getting out of a bed/chair, feeding oneself, dressing oneself, bathing/showering oneself, and getting to or using the toilet

On average, people were followed for 7 years. During follow-up, 946 (24%) people were diagnosed with dementia, including 752 (19%) with AD; additionally, 26% died, 9% disenrolled, and 42% reached the current end of study follow-up before a diagnosis of dementia. The adjusted hazard for dementia or AD was not increased among people with high-risk surgery with general anesthesia compared to the reference group (no anesthesia) (HR=0.86, 95%CI=0.58–1.28 for dementia; HR=0.95, 95%CI=0.61–1.49 for AD) (Table 2). The adjusted HRs for other surgery with general anesthesia and their confidence intervals were below 1, suggesting a reduced risk of dementia. None of the HRs suggested strong evidence for associations between recent anesthesia exposure and risk of dementia or AD. When comparing the results for high-risk surgery with general anesthesia directly to other surgery with general anesthesia (to explore for an association with high-risk surgery above and beyond that of general anesthesia), the HRs were 1.37 (95%CI=1.04–1.80) for dementia and 1.46 (95%CI=1.07–1.99) for AD. When we evaluated the cumulative number of surgeries with general anesthesia (data not shown) results we did not note any dose-response.

Table 2.

Risks of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Associated with Surgery and Anesthesia Exposuresa

| Ever exposed | Follow-up time (person-years) |

Dementia | Alzheimer’s disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events | Adjusted hazard ratiob (95% confidence interval) |

Number of events | Adjusted hazard ratiob (95% confidence interval) |

||

| No anesthesia | 1,384 | 54 | 1 | 43 | 1 |

| High-risk surgery with general anesthesia | 2,230 | 97 | 0.86 (0.58, 1.28) | 80 | 0.95 (0.61, 1.49) |

| Other surgery with general anesthesia | 25,178 | 778 | 0.63 (0.46, 0.85) | 614 | 0.65 (0.46, 0.93) |

| Other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia | 783 | 17 | 0.49 (0.26, 0.90) | 15 | 0.62 (0.32, 1.19) |

| Recent exposure in past 5 years | |||||

| No anesthesia | 19,815 | 644 | 1 | 525 | 1 |

| High-risk surgery with general anesthesia | 799 | 23 | 0.80 (0.48, 1.34) | 17 | 0.64(0.34, 1.22) |

| Other surgery with general anesthesia | 7860 | 255 | 0.87(0.74, 1.03) | 196 | 0.82(0.68, 1.00) |

| Other surgery with neuraxial anesthesia | 1101 | 24 | 0.83 (0.54, 1.28) | 14 | 0.66 (0.38, 1.14) |

Anesthesia/surgery categories are hierarchical and mutually exclusive although people could contribute person-time to more than one group during follow-up; reference group for each hazard ratio is no anesthesia

Adjusted for ACT study cohort, age (via the time axis), age at ACT study entry, gender, education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, stroke, coronary heart disease, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health, depression, Parkinson’s disease, Charlson comorbidity score, and difficulty with activities of daily living. Analyses for recent exposure in past 5 years also adjusted for prior surgery more than 5 years ago.

In sensitivity analyses limited to surgeries before age 65 or excluding labor-related procedures, the associations between anesthesia exposures and dementia or AD outcomes were attenuated toward the null. Excluding high risk surgeries on the brain did not change our results.

DISCUSSION

Our primary results do not support an increased risk of dementia or AD following lifetime or recent anesthesia exposure in older adults. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest population-based studies with data on anesthesia exposure to evaluate this association.(13) These results may help quell the perception that anesthesia exposure increases risk of dementia and AD.

Our results were similar to those from previous case-control studies, which have demonstrated no association between anesthesia and AD. Authors of a recent review and meta-analysis used Newcastle-Ottawa criteria (22) to identify “high quality” case-control studies.(12) Two of the four high quality studies they identified had non-significant odds ratios below 1.0. (23) (24) Recall bias in prior studies may help explain results from two prior studies that show anesthesia exposure increases dementia and AD risk.(9, 15)

Exposure to general anesthesia within the last 5 years was not associated with subsequent risk of dementia or AD in our study. This result should be reassuring to older patients, their families, and providers when considering surgery late in life. We are unaware of any other studies that have examined recent anesthesia exposure. Sprung et al. (14) limited analyses to general anesthesia exposure after age 45 and found a non-significant association with dementia (OR=0.89, 95%CI=0.73–1.10) similar to our results for recent exposure.

We attempted to explore whether the stress of surgery was associated with dementia or AD, above and beyond general anesthesia exposure, by directly comparing high-risk surgeries to all other procedures involving general anesthesia. The risks of dementia and AD associated with high-risk surgery relative to other surgery with general anesthesia were statistically significantly increased. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that high-risk surgery adds additional stress that often leads to post-operative delirium, and subsequently dementia or AD.(10, 11) Additional studies are needed to confirm this observation. It is also possible that there are underlying medical conditions that contribute to the need for high-risk surgery and are also risk factors for dementia, confounding this association.

A major strength of our study is that all surgical procedures with anesthesia were recorded before the onset of dementia or AD. Our outcomes of dementia and AD were also assessed prospectively and defined using standard criteria. Finally, our analysis takes advantage of a large, population-based community cohort of older adults; with nearly 4000 study participants, this is one of the largest studies on anesthesia use and dementia outcomes to date.

Limitations include that exposure data were collected via self-report and were not confirmed by medical record review. In addition, exposures collected at baseline may be subject to recall limitations. We did not have information on the specific medications used or the duration of anesthesia. Although we attempted to disentangle surgery and anesthesia exposures, such efforts are inherently limited because of the strong correlation between the two: typically, no patients undergo anesthesia without undergoing surgery – and no one undergoes surgery without anesthesia. Finally, as with all observational studies, our results may be limited by residual confounding.

CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that anesthesia is not associated with an increased risk of dementia or AD in older adults. Future studies should continue to explore whether there is truly an increased risk of dementia and AD following high-risk surgery.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant U01AG006781 and by the Branta Foundation.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Larson receives royalties from UpToDate. Rod Walker has received funding as a biostatistician from a research grant awarded to Group Health Research Institute from Pfizer. Onchee Yu has received funding as a biostatistician from research grants awarded to Group Health Research Institute from Amgen and Bayer. Dr. Dublin received a Merck/American Geriatrics Society New Investigator Award.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design (Erin J. Aiello Bowles, SD), acquisition of subjects and/or data (Eric B. Larson, PKC), analysis and interpretation of data (Erin J. Aiello Bowles, Ryan P. Pong, Rod L. Walker, Melissa L. Anderson, Onchee Yu, Shelly L. Gray, Sascha Dublin), preparation of manuscript (Erin J. Aiello Bowles, Eric B. Larson, Ryan P. Pong, Rod L. Walker, Melissa L. Anderson, Onchee Yu, Shelly L. Gray, Paul K. Crane, Sascha Dublin), obtaining funding (Sascha Dublin, Eric B. Larson, Paul K. Crane)

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of this paper.

References

- 1.Buie VC, Owings MF, DeFrances CJ, et al. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2006 summary. Vital Health Stat: National Center for Health Statistics. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avidan MS, Evers AS, Planel E, et al. Review of clinical evidence for persistent cognitive decline or incident dementia attributable to surgery or general anesthesia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:201–216. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong HK, Sands LP, Leung JM. The role of postoperative analgesia in delirium and cognitive decline in elderly patients: A systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1255–1266. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000198602.29716.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craddock TJ, St George M, Freedman H, et al. Computational predictions of volatile anesthetic interactions with the microtubule cytoskeleton: Implications for side effects of general anesthesia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papon MA, Whittington RA, El-Khoury NB, et al. Alzheimer’s disease and anesthesia. Front Neurosci. 2011;4:272. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Planel E, Krishnamurthy P, Miyasaka T, et al. Anesthesia-induced hyperphosphorylation detaches 3-repeat tau from microtubules without affecting their stability in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12798–12807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4101-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planel E, Richter KE, Nolan CE, et al. Anesthesia leads to tau hyperphosphorylation through inhibition of phosphatase activity by hypothermia. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3090–3097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4854-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittington RA, Bretteville A, Dickler MF, et al. Anesthesia and tau pathology. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain M, Berger M, Eckenhoff RG, et al. General anesthetic and the risk of dementia in elderly patients: Current insights. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1619–1628. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S49680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerejeira J, Batista P, Nogueira V, et al. The stress response to surgery and postoperative delirium: Evidence of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperresponsiveness and decreased suppression of the GH/IGF-1 Axis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2013;26:185–194. doi: 10.1177/0891988713495449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deiner S, Silverstein JH. Postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103(Suppl 1):41–46. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seitz DP, Shah PS, Herrmann N, et al. Exposure to general anesthesia and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seitz DP, Reimer CL, Siddiqui N. A review of epidemiological evidence for general anesthesia as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sprung J, Jankowski CJ, Roberts RO, et al. Anesthesia and incident dementia: A population-based, nested, case-control study. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2013;88:552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CW, Lin CC, Chen KB, et al. Increased risk of dementia in people with previous exposure to general anesthesia: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: A prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1737–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells GAS, Shea D, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 23.Tyas SL, Manfreda J, Strain LA, et al. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based, longitudinal study in Manitoba, Canada. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:590–597. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yip AG, Brayne C, Matthews FE, et al. Risk factors for incident dementia in England and Wales: The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. A population-based nested case-control study. Age Ageing. 2006;35:154–160. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]