Abstract

Objective:

Personalized normative feedback (PNF) has been used extensively to reduce alcohol consumption, particularly among heavy drinkers. However, the majority of PNF studies have used only descriptive norms (real or perceived pervasiveness of a given behavior). The purpose of the current study was to explore the efficacy of PNF both with and without an injunctive message indicating approval or disapproval based on the participants’ standing relative to other students’ drinking levels. This randomized trial evaluated two brief web-based alcohol intervention conditions (descriptive-norms-feedback–only condition versus a descriptive-plus-injunctive-message condition relative to an assessment-only control condition).

Method:

Participants included 176 students who had reported at least one heavy drinking episode in the past month. Participants completed baseline and follow-up assessments of perceived norms and drinking. Follow-up assessments were completed at 2 weeks post-intervention by 165 (94%) participants.

Results:

Analyses were conducted using zero-inflated negative binomial regression models. As expected, the descriptive-norms–only condition was effective in reducing drinking among heavier baseline drinkers at follow-up relative to the control condition. However, contrary to expectations, the descriptive-plus-injunctive-message condition did not predict less drinking at follow-up.

Conclusions:

This study was unique in using an injunctive message as an adjunct to descriptive-norms feedback within the context of drinking. Findings highlight the need for additional research into the role of defensiveness, which may serve as an impediment to using injunctive norms/messages in interventions for problematic substance use and other potentially stigmatizing behaviors.

Individuals are strongly influenced by their perceptions of others’ attitudes and behaviors (e.g., perceived social norms; Asch, 1956; Cialdini et al., 1990; Deutsch & Gerrard, 1955; Sherif, 1936). Thus, social norms interventions have been explored in domains including reuse of hotel towels (Schultz et al., 2008), promotion of taking the stairs versus the elevator (Burger & Shelton, 2011), and reduction of littering (Cialdini et al., 1990). Recently, studies have focused on how social norms affect health behaviors, including exercise, diet, and smoking cessation (Ball et al., 2010; Burger et al., 2010; Zaleski & Aloise-Young, 2013). The current research uses personalized descriptive normative feedback (PNF) with and without an injunctive message in an alcohol-related intervention.

Misperceived norms

Despite the potential for social norms to positively influence people, individuals often misperceive them. Individuals may avoid expressing negative attitudes about drinking because they incorrectly believe that they are in the minority. This pluralistic ignorance results in a silent majority incorrectly perceiving that others are drinking more than they actually are (Miller & McFarland, 1991; Prentice & Miller, 1993; Toch & Klofas, 1984). Conversely, with the false consensus effect (Marks & Miller, 1987; Ross et al., 1977), individuals overestimate the degree to which others agree with or engage in the behaviors that they themselves participate in. Thus, heavier drinkers may continue excessive consumption because they perceive their drinking to be “normal.” Both misperceptions have important implications for drinking.

College drinking and misperceived norms

Thirty-five percent of college students (Johnston et al., 2014) report having engaged in heavy episodic drinking at least once in the past 2 weeks (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009; Wechsler et al., 2002). Moreover, alcohol-related consequences can be severe (e.g., Hingson et al., 2009); thus, research is needed to better understand the social influences surrounding this at-risk group. Alcohol-related social norms interventions, which present accurate normative feedback to correct over-estimations of peer drinking, appear promising in combating misperceived norms (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003; Martens et al., 2013; Neighbors et al., 2004).

Descriptive and injunctive norms

Two distinct types of norms have often been considered (Cialdini, 2003; Cialdini et al., 1990, 2006). Descriptive norms refer to actual or perceived prevalence of a given behavior. For example, an individual might observe peers drinking and derive a perceived number of drinks consumed. Alternatively, injunctive norms refer to perceived degree of approval of a given behavior (e.g., the perception that peers condone or encourage drinking).

PNF is a commonly used paradigm within the alcohol-related social norms literature (e.g., Martens et al., 2013; Neighbors et al., 2010; Prince et al., 2014). PNF corrects misperceived norms by presenting participants with feedback based on (a) their self-reported drinking, (b) their perceptions of their peers’ drinking, and (c) actual descriptive norms. PNF highlights potential disparities between perceived and actual descriptive norms, thereby reducing consumption among heavy drinkers (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2004, 2010).

Interestingly, although research has examined both norms in changing behaviors (e.g., Cialdini et al., 2006; Mollen et al., 2013; Panagopoulos et al., 2014), alcohol-focused interventions have almost exclusively used descriptive norms. A review examining drinking-related, feedback-based interventions found that 98% included descriptive norms (Miller et al., 2013). Furthermore, studies that have incorporated injunctive components in alcohol interventions have provided equivocal results. For example, Schroeder and Prentice (1998) found that group discussions about pluralistic ignorance of alcohol approval relative to a comparison group was associated with reduced drinking, but there were no differences in perceived injunctive norms. Moreover, because they are typically operationalized, perceived injunctive norms are inconsistently (and sometimes even negatively) associated with drinking, depending on the reference group or whether descriptive norms are controlled for (Collins & Spelman, 2013; LaBrie et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2008).

Outside of the alcohol domain, Schultz and colleagues (2007) found that a simple injunctive message of approval or disapproval (operationalized as an emoticon) enhanced the effects of descriptive norms feedback on energy consumption. Specifically, they found that presenting households with the descriptive norms alone yielded mixed results. House-holds that were above the descriptive norms lowered their energy consumption (the desired effect), whereas households below the descriptive norms increased their energy consumption (the undesired effect). However, when the injunctive message (conveyed through a happy or sad face) was added to the descriptive norms, households both above and below the descriptive norms exhibited the desired lower rate of energy consumption.

Current study

We randomly assigned heavy drinking participants to one of three conditions: descriptive-only, descriptive-plus-injunctive, and assessment-only (control). Specifically, we compared the descriptive-only and the descriptive-plus-injunctive conditions to the control condition. Based on previous studies (e.g., Lewis & Neighbors, 2007; Martens et al., 2013), we expected that the descriptive-only condition would predict less drinking at follow-up. Additionally, we hypothesized that the descriptive-plus-injunctive condition would predict less drinking at follow-up relative to the descriptive-only condition. The overarching goal was to explore the utility of an injunctive message as an adjunct to alcohol-related descriptive-norms feedback.

Method

Participants

Participants included 176 students who reported at least one heavy drinking episode in the past month. Participants were recruited via flyers and in-class announcements at a large southern university. Respondents were 18 years or older (Mage = 23.25 years, SD = 4.96). Only participants who reported at least one heavy drinking episode (4+ drinks for women/5+ drinks for men) in the past month during an online prescreen qualified. Participants were predominantly female (82%). The sample was racially (16% Asian/Pacific Islander, 14% Black, 46% White, 4% multiethnic, 20% other) and ethnically (42% Hispanic) diverse.

Procedure

The study consisted of an in-laboratory baseline assessment and a 2-week follow-up assessment. During the 45-minute baseline session, participants completed alcohol-related measures online. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: descriptive-only, descriptive-plus-injunctive, or assessment-only (control). In the descriptive-only condition, participants received gender-specific PNF (e.g., “According to a recent survey of over 1,000 [university acronym] students, the average MALE [university acronym] student drinks: 4.2 drinks per week, 1.2 days per week, and 3.2 drinks per occasion.”). They also received their percentage of alcoholic intake relative to same-sex students. Descriptive norms were based on a large 2011 survey assessing campus drinking norms. The descriptive-plus-injunctive condition received the same feedback as the descriptive-only condition, with the addition of an emoticon to represent an injunctive message (happy face if at or below average drinking of same-sex peers; sad face if above). The control condition received no feedback. Two weeks later, participants were e-mailed a link to the 15-minute follow-up. Ninety-four percent (165 of 176) of the participants completed both components.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants completed demographic information, including age, gender, ethnicity, and race.

Participants’ self-reported drinking.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) asked participants to report how many alcoholic beverages they were likely to have consumed on each day of a typical week during the past 3 months (baseline) and a typical week during the past 2 weeks (follow-up). Participants’ baseline DDQ responses were used to create PNF on drinks per week, times they drank per week, and drinks per occasion.

Peer drinking habits.

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer et al., 1991) is similar to the DDQ but assesses participants’ perceptions of same-sex students’ drinking. Participants’ DNRF responses were used to create PNF regarding their perceptions of their same-sex peers’ drinking (e.g., perceived drinks per week, times they drank per week, and drinks per occasion).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Respondents were distributed proportionally across the control (n = 57), descriptive-only (n = 55), and descriptive-plus-injunctive (n = 53) conditions, χ2(2) = 0.15, p = .93. DDQ scores exhibited a significant decrease, t(164) = 5.74, p < .01, d = .45, from baseline (M = 8.17, SD = 7.90) to follow-up (M = 5.84, SD = 6.79), and the distribution of DDQ scores (i.e., the typical number of drinks per week) was highly skewed and leptokurtic at both baseline (S = 3.06, K = 12.82) and follow-up (S = 3.46, K = 17.57).

Analysis strategy

A nontrivial number of zeros (13%; n = 21) were observed for follow-up DDQ. Thus, zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB; Atkins & Gallop, 2007), which models the structured-zero and count portions of the distribution independently, was used. The intervention conditions were represented by a pair of dummy-coded vectors designating membership in the descriptive-only (Descriptive) and descriptive-plus-injunctive (Descript + Injunct) conditions, with the control as the reference group. Baseline DDQ scores were centered around the median (Mdn = 6) and were included as a moderator variable to examine whether the treatment effect varied as a function of baseline drinking (Royston & Sauerbrei, 2008; Sauerbrei et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2014).

Primary analysis

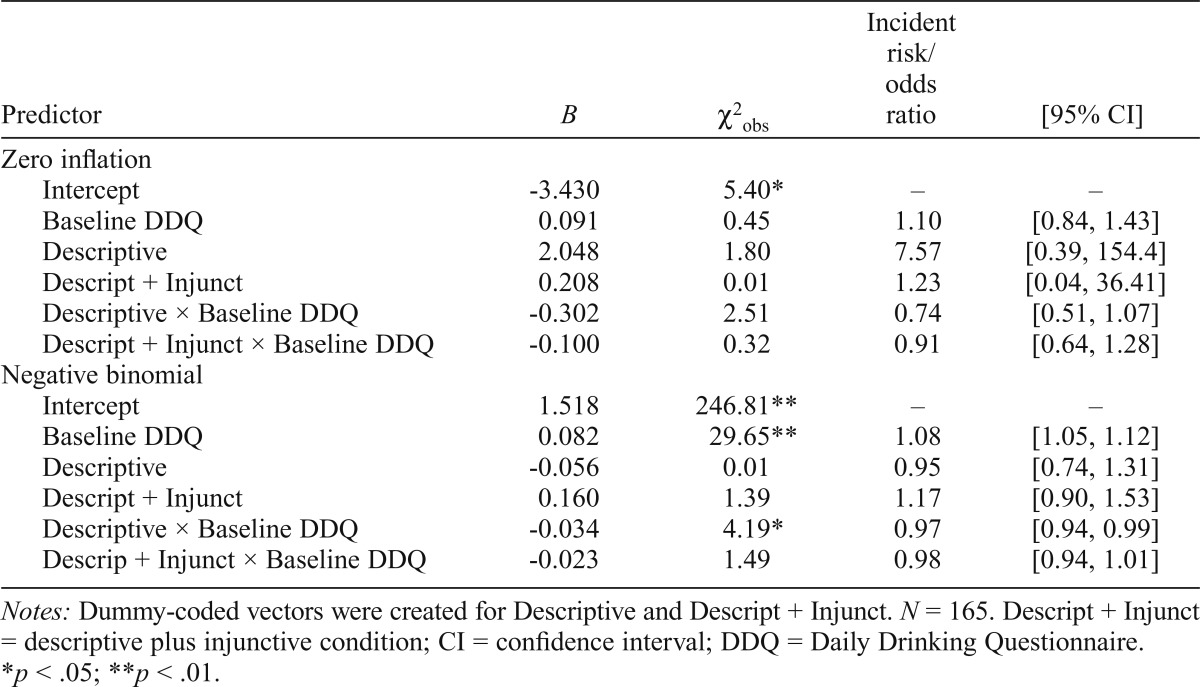

Parameter estimates for the structured-zero component are provided at the top of Table 1; estimates for the negative binomial (NB) portion of the model are presented in the bottom. Including the Descriptive × Baseline DDQ and Descript + Injunct × Baseline DDQ interactions means that the observed intercept and first-order effects for Descriptive and Descript + Injunct conditions represent simple effects for individuals reporting a median level of baseline drinking (i.e., 6 drinks). It is important to note that this coding scheme means that the first-order coefficient for Baseline DDQ represents the simple effect of this predictor in the control condition.

Table 1.

Changes in drinking at follow-up as a function of intervention conditions

| Predictor | B | χ2obs | Incident risk/odds ratio | [95% CI] |

| Zero inflation | ||||

| Intercept | -3.430 | 5.40* | – | – |

| Baseline DDQ | 0.091 | 0.45 | 1.10 | [0.84, 1.43] |

| Descriptive | 2.048 | 1.80 | 7.57 | [0.39, 154.4] |

| Descript + Injunct | 0.208 | 0.01 | 1.23 | [0.04, 36.41] |

| Descriptive × Baseline DDQ | -0.302 | 2.51 | 0.74 | [0.51, 1.07] |

| Descript + Injunct × Baseline DDQ | -0.100 | 0.32 | 0.91 | [0.64, 1.28] |

| Negative binomial | ||||

| Intercept | 1.518 | 246.81** | – | – |

| Baseline DDQ | 0.082 | 29.65** | 1.08 | [1.05, 1.12] |

| Descriptive | -0.056 | 0.01 | 0.95 | [0.74, 1.31] |

| Descript + Injunct | 0.160 | 1.39 | 1.17 | [0.90, 1.53] |

| Descriptive × Baseline DDQ | -0.034 | 4.19* | 0.97 | [0.94, 0.99] |

| Descrip + Injunct × Baseline DDQ | -0.023 | 1.49 | 0.98 | [0.94, 1.01] |

Notes: Dummy-coded vectors were created for Descriptive and Descript + Injunct. N = 165. Descript + Injunct = descriptive plus injunctive condition; CI = confidence interval; DDQ = Daily Drinking Questionnaire.

p < .05;

p < .01.

None of the coefficients emerged as significant in the zero-inflation analysis (all ps >.11). Turning to the NB analysis, a significant simple effect of Baseline DDQ emerged, B = 0.082, χ2(1) = 29.65, p < .01, incident risk ratio (IRR) = 1.08, suggesting that, for participants in the control condition, greater baseline drinking was associated with more drinking at follow-up. The first-order effects for Descriptive and Descript + Injunct failed to reach significance (both ps > .23), suggesting that the descriptive-only or descriptive-plus-injunctive feedback did not influence follow-up drinking (relative to the control condition) for participants reporting typical levels of baseline consumption (i.e., 6 drinks/week). However, a significant Descriptive × Baseline DDQ, B = -0.034, χ2(1) = 4.19, p < .05, emerged, suggesting that the effect of the condition was dependent on the participants’ baseline drinking. To examine this interaction more precisely, conditional effects of the Descriptive condition were estimated using the simple-slopes approach (Aiken & West, 1991). Given the skewed distribution of the moderating variable (Baseline DDQ), a value of 2 drinks (reported by 12% of the sample) was chosen for the lower value, and 15 drinks or fewer (92% of the sample) was chosen for the higher value.

For participants reporting lower levels of baseline drinking (i.e., 2 drinks/week), the effect of the Descriptive condition failed to reach significance (p = .45), suggesting that providing lighter drinkers with descriptive-only feedback had no effect on the number of drinks consumed at follow-up; however, among heavy baseline drinkers, the simple effect of the Descriptive condition was negative and just shy of the critical p value. The direction of this simple effect, B = -0.319, χ2(1) = 3.70, p = .054, IRR = 0.73, suggests that receiving the descriptive feedback lowered levels of follow-up drinking among participants who reported greater baseline drinking.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of a descriptive-only and a descriptive-plus-injunctive condition against a control condition among a group of heavy drinkers. It is one of the first of its kind to explore the effect of combining descriptive norms with an injunctive message as a web-based intervention. For the structured-zero portion of the ZINB (the probability of reporting zero drinks), neither the descriptive-only nor the descriptive-plus-injunctive condition had an effect. However, in the NB model (nonzero drinks), a significant conditional effect of the descriptive-only condition emerged, suggesting lower levels of drinking at follow-up. Simple-slopes analysis further split heavy drinkers into “low” and “high” groups, thus isolating the heaviest drinkers. Results revealed that the heaviest drinkers in the descriptive-only condition drank less at follow-up. Thus, more extreme norms feedback given to the heaviest drinkers (i.e., “You drink more than 95% of students” vs. “…35% of students”) may have influenced them to drink less. This finding is particularly important, as descriptive norms could be a cost-effective way of reducing drinking among those most at risk.

However, the addition of an injunctive message did not lead to lower levels of drinking. These findings are a departure from research in other domains (e.g., Burger & Shelton, 2011; Cialdini et al., 1990), which shows a unique additive effect when an injunctive message is combined with a descriptive norm.

The present work provides an important conceptual replication and extension of Schultz et al.’s (2007) energy-consumption study, which found the addition of the injunctive message to the descriptive norm to be efficacious. Although we generally replicated their procedures, some notable differences may account for the differential results. First, Schultz et al. used a two-group pretest–posttest design and analyzed a continuous outcome variable. Our study used a three-group pretest–posttest design using a smaller (albeit sufficient) sample, with a count outcome variable. This combination of factors may have led to lower power in our study. Second, participants in our study received feedback at only one time point (rather than two), which may not be as effective in influencing behavior, especially for heavier drinkers who may be more accustomed to higher drinking levels. Third, Schultz et al. (2007) provided information about how to reduce energy consumption along with the feedback. Although our procedure is consistent with those of other alcohol-related social norms interventions (e.g., Martens et al., 2013; Neighbors et al., 2010), it is possible that providing strategies to reduce drinking along with the feedback might result in lower drinking levels.

Furthermore, for heavier drinkers, the sad face emoticon may have provoked defensiveness in that participants felt judged. This may have been because they viewed it as a form of negative evaluation, which, in turn, may have posed an ego threat. Similar drinking intervention studies have found that more threatening messages may increase intentions to drink, especially among heavy drinkers (Bensley & Wu, 1991). However, participants may become less defensive over time. Repeated exposure of injunctive messages has been found to be effective in reducing smoking (Kessels et al., 2010), drinking (Brown & Locker, 2009), and risky sexual behavior (Earl et al., 2009).

Previous studies that used injunctive-plus-descriptive norms successfully had targeted socially acceptable behavior (e.g., Schultz et al., 2008; promoting environmental conservation), rather than stigmatized behaviors (e.g., drinking). In addition, heavier drinkers might have peer groups that support (or accommodate) their drinking, and this may have been a more direct and personal influence than the injunctive message. In fact, it is possible that participants may have understood the injunctive message as being the investigators’ feelings about their drinking rather than the perception of their peers. Thus, a limitation of this study is that the emoticon may not have been perceived as disapproval by other students. However, our study highlights the need for additional research on understanding the role of defensiveness and for additional research into the effect of an injunctive message. This may help to inform future injunctive norms/messages interventions involving stigmatized behaviors.

Limitations and future directions

The strengths of the present research should be considered in light of its limitations. The present study had a relatively low number of men; thus, the results may not be representative of heavy-drinking men. In addition, some participants reported minimal drinking after initially qualifying for the study. Finally, the 2-week follow-up does not allow for evaluation of longer-term effects of the PNF, and the differential assessment time frame (past 3 months at baseline vs. 2 weeks at follow-up) precludes conclusive interpretation of within-group drinking reductions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Rodriguez and Ela Karacevic for their hard work in contributing to the data collection and the recruitment of participants for this study. In addition, the authors acknowledge Ela Karacevic for her contribution in helping to edit and proofread the article.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant R01AA014576. The NIAAA had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asch S. E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied. 1956;70:1–70. doi:10.1037/h0093718. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins D. C., Gallop R. J. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer J. S., Stacy A., Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. doi:10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K., Jeffery R. W., Abbott G., McNaughton S. A., Crawford D. Is healthy behavior contagious: Associations of social norms with physical activity and healthy eating. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7:86. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-86. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley L. S., Wu R. The role of psychological reactance in drinking following alcohol prevention messages. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1991;21:1111–1124. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1991.tb00461.x. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Carey K. B. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Locker E. Defensive responses to an emotive anti-alcohol message. Psychology & Health. 2009;24:517–528. doi: 10.1080/08870440801911130. doi:10.1080/08870440801911130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. M., Bell H., Harvey K., Johnson J., Stewart C., Dorian K., Swedroe M. Nutritious or delicious? The effect of descriptive norm information on food choice. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:228–242. doi:10.1521/jscp.2010.29.2.228. [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. M., Shelton M. Changing everyday health behaviors through descriptive norm manipulations. Social Influence. 2011;6:69–77. doi:10.1080/15534510.2010.542305. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:105–109. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01242. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Demaine L. J., Sagarin B. J., Barrett D. W., Rhoads K., Winter P. L. Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence. 2006;1:3–15. doi:10.1080/15534510500181459. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Reno R. R., Kallgren C. A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Parks G. A., Marlatt G. A. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. E., Spelman P. J. Associations of descriptive and reflective injunctive norms with risky college drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:1175–1181. doi: 10.1037/a0032828. doi:10.1037/a0032828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M., Gerard H. B. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1955;51:629–636. doi: 10.1037/h0046408. doi:10.1037/h0046408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl A., Albarracín D., Durantini M. R., Gunnoe J. B., Leeper J., Levitt J. H. Participation in counseling programs: High-risk participants are reluctant to accept HIV-prevention counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:668–679. doi: 10.1037/a0015763. doi:10.1037/a0015763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R. W., Zha W., Weitzman E. R. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;(Supplement 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. doi:10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E., Miech R. A. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2013: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19-55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels L. T. E., Ruiter R. A. C., Jansma B. M. Increased attention but more efficient disengagement: Neuroscientific evidence for defensive processing of threatening health information. Health Psychology. 2010;29:346–354. doi: 10.1037/a0019372. doi:10.1037/a0019372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J. W., Hummer J. F., Neighbors C., Larimer M. E. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. A., Neighbors C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:228–237. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G., Miller N. Ten years of research on the false-consensus effect: An empirical and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:72–90. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.1.72. [Google Scholar]

- Martens M. P., Smith A. E., Murphy J. G. The efficacy of single-component brief motivational interventions among at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:691–701. doi: 10.1037/a0032235. doi:10.1037/a0032235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. B., Leffingwell T., Claborn K., Meier E., Walters S., Neighbors C. Personalized feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: An update of Walters & Neighbors (2005) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:909–920. doi: 10.1037/a0031174. doi:10.1037/a0031174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. T., McFarland C. When social comparison goes awry: The case of pluralistic ignorance. In: Suls J., Wills T. A., editors. Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- Mollen S., Rimal R. N., Ruiter R. A. C., Kok G. Healthy and unhealthy social norms and food selection: Findings from a field-experiment. Appetite. 2013;65:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.020. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Larimer M. E., Lewis M. A. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., Lewis M. A., Atkins D. C., Jensen M. M., Walter T., Fossos N., Larimer M. E. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. doi:10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C., O’Connor R. M., Lewis M. A., Chawla N., Lee C. M., Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. doi:10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos C., Larimer C. W., Condon M. Social pressure, descriptive norms, and voter mobilization. Political Behavior. 2014;36:451–469. doi:10.1007/s11109-013-9234-4. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice D. A., Miller D. T. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. A., Reid A., Carey K. B., Neighbors C. Effects of normative feedback for drinkers who consume less than the norm: Dodging the boomerang. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:538–544. doi: 10.1037/a0036402. doi:10.1037/a0036402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L., Greene D., House P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13:279–301. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P., Sauerbrei W. Interactions between treatment and continuous covariates: A step toward individualizing therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:1397–1399. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8981. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbrei W., Royston P., Zapien K. Detecting an interaction between treatment and a continuous covariate: A comparison of two approaches. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2007;51:4054–4063. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2006.12.041. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder C. M., Prentice D. A. Exposing pluralistic ignorance to reduce alcohol use among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:2150–2180. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01365.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P. W., Khazian A. M., Zaleski A. C. Using normative social influence to promote conservation among hotel guests. Social Influence. 2008;3:4–23. doi:10.1080/15534510701755614. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P. W., Nolan J. M., Cialdini R. B., Goldstein N. J., Griskevicius V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychological Science. 2007;18:429–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. The psychology of social norms. New York, NY: Harper; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. 2009 Retrieved from http://archive.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/2k9Results.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Alizadeh A. A., Gentles A. J., Tibshirani R. A simple method for estimating interactions between a treatment and a large number of covariates. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2014;109:1517–1532. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2014.951443. doi:10.1080/01621459.2014.951443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toch H., Klofas J. Pluralistic ignorance, revisited. In: Stephenson G. M., Davis J. H., editors. Progress in applied social psychology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 1984. pp. 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Lee J. E., Kuo M., Seibring M., Nelson T. F., Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. doi:10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski A. C., Aloise-Young P. A. Using peer injunctive norms to predict early adolescent cigarette smoking intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013;43(Supplement 1):E124–E131. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12080. doi:10.1111/jasp.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]