Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To systematically review the literature on the impact of patient navigators on cancer screening for limited English proficient (LEP) patients.

DATA SOURCES

Electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO via OVID, Web of Science, Cochrane, EMBASE, and Scopus) through 8 May 2015.

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

Articles in this review had: (1) a study population of LEP patients eligible for breast, cervical or colorectal cancer screenings, (2) a patient navigator intervention to provide services prior to or during cancer screening, (3) a comparison of the patient navigator intervention to either a control group or another intervention, and (4) language-specific outcomes related to the patient navigator intervention.

STUDY APPRAISAL

We assessed the quality of the articles using the Downs and Black Scale.

RESULTS

Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria and evaluated the screening rates for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer in 15 language populations. Fourteen studies resulted in improved screening rates for LEP patients between 7 and 60 %. There was great variability in the patient navigation interventions evaluated. Training received by navigators was not reported in nine of the studies and no studies assessed the language skills of the patient navigators in English or the target language.

LIMITATIONS

This study is limited by the variability in study designs and limited reporting on patient navigator interventions, which reduces the ability to draw conclusions on the full effect of patient navigators.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, we found evidence that navigators improved screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening for LEP patients. Future studies should systematically collect data on the training curricula for navigators and assess their English and non-English language skills in order to identify ways to reduce disparities for LEP patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3572-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: language, communication barriers, limited English proficiency, patient navigators

BACKGROUND

More than 58 million Americans, 20.3 % of the U.S. population, speak a language other than English at home,1 with Spanish, Chinese, French, Tagalog and Vietnamese being the most frequently spoken languages.2 Of these individuals, nearly 25 million reported that they speak English less than “very well” or are limited English proficient (LEP).1 LEP persons have difficulty reading, writing and understanding English,3 which creates obstacles to participation in the English-language dominant healthcare system. Language barriers play a significant role in poor health processes and outcomes,4–7 including reduced accessing of preventive services8,9 and cancer screening rates among LEP patients.10–13 These obstacles to cancer screenings for LEP patients can be reduced with language assistance. Patient navigation is a promising intervention to eliminate language as a barrier to cancer screening for LEP patients.

The purpose of patient navigation is to ameliorate barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment of cancer and other chronic illnesses.14 Patient navigation is defined as a “patient-centered healthcare service delivery model” that aims to assist the individual patient in maneuvering through the complex and disconnected healthcare system to eliminate barriers to timely care. Patient navigation has been proven to be an effective strategy to improve cancer screening rates in vulnerable populations in the US, such as those with low socioeconomic status. Two reviews have evaluated the impact of patient navigators on cancer screening and found that when patient navigators are provided, patients are significantly more likely to complete screenings for breast, cervical and/or colorectal cancer.15,16 Neither of these reviews specifically investigated the impact of patient navigation on cancer screening for LEP patients.

Patient navigation has been brought to greater prominence as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Enacted in October 2013, the ACA includes accessibility standards that require all information to be in plain language that is culturally and linguistically responsive to LEP persons.17 The ACA requires patient navigator programs to be established for each state with a health insurance exchange to assist individuals in making informed decisions regarding their healthcare coverage plans. To our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the impact of these services for LEP populations. With this review, we hope to define the best research strategy to evaluate this healthcare intervention.

While the patient navigator model has proven effective in improving care for underserved communities, its impact on the LEP population has yet to be explored. The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to understand the effect of patient navigators who work to both bridge language barriers and improve cancer screening rates for LEP patients. We provide a systematic review of the current literature, assessed the quality of studies, identified gaps in the literature for further exploration, and provided recommendations for research and clinical practice to reduce disparities in cancer screening rates for LEP patients. We hypothesize that patient navigators will positively impact the screening rates of LEP patients.

METHODS

Data sources

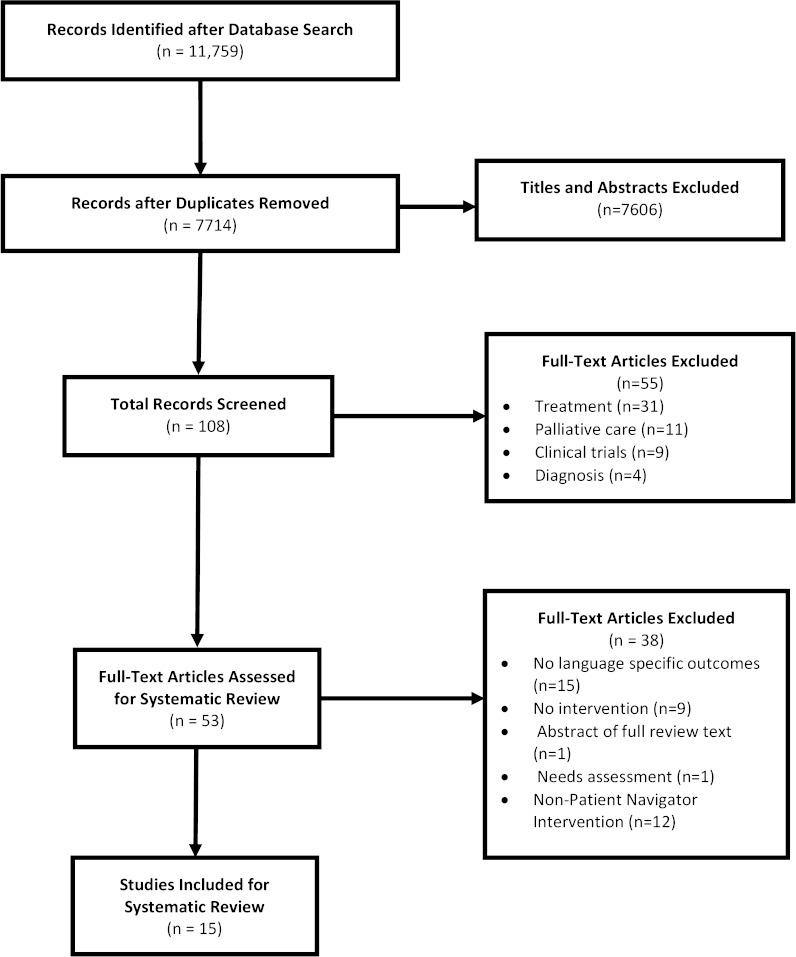

We searched six databases for this systematic review: PubMed (from 1945 to May, 2015), PsycINFO (Psychological Abstracts) via OVID (from 1860 to May, 2015), Web of Science (from 1966 to May, 2015), Cochrane (from 1898 to May, 2015), EMBASE (from 1966 to May, 2015), and Scopus (from 1960 to May, 2015). The literature search strategy had three main components, which were linked together with ‘AND’: (1) cancer; (2) medical interpretation; and (3) immigrant/minority status. For PubMed, the controlled vocabulary Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) was used. We searched for articles in any available language. After removing duplicates, this search provided 7714 articles. The online appendix represents the full strategy used to search the literature. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA Flow Diagram.18

Figure 1.

Prisma diagram of search and selection criteria.

Study Selection

The article review screened for studies that evaluated language assistance interventions to increase the cancer screening rates for LEP patients, which included patient navigators, bilingual staff, professional interpreters, health educators and family members. A systematic title and abstract review was conducted by two authors (AZ and MG) using the PICO framework (Fig. 1).19 The following inclusion criteria were applied to the 7714 articles: (1) the study population included LEP patients who needed cancer care, (2) there was an intervention to provide language services prior to or during cancer care, (3) there was a comparison of the language service intervention to either a control group or another intervention, and (4) there was an assessment of the outcomes of the language service intervention. Articles were eliminated without further review if they did not focus specifically on language service use and cancer care. These excluded articles that evaluated pharmaceuticals, radiology technologies, validity of translated scales, communication interventions for English speaking patients, covered acculturation and health care, or cross-cultural health care without a focus on language. Articles were also excluded if they assessed interventions with American Sign Language interpreters, because, while people who are deaf or hard of hearing also face communication barriers, sign language interpreters face different challenges than non-English language interpreters and the laws protecting a deaf or hard of hearing patient’s right to an interpreter are stricter than those for LEP patients. After the title and abstract review, 7605 articles were excluded, resulting in a full review of 108 articles. Articles were then excluded that were not directly related to cancer screening, including those focused on cancer treatment (n = 31), palliative care (n = 11), clinical trial participation (n = 9), and cancer diagnosis (n = 4). This left 53 articles that specifically addressed cancer screening. During full text review, 26 articles were eliminated because they were primarily descriptive studies of single-site programs to increase screening for LEP patients that did not focus the results on the effects of a language service use intervention. An additional 12 articles were excluded because the language service use intervention involved staff who were not patient navigators. A total of 15 articles were included in the review.

Data Abstraction

Three of the authors (AZ, MG. and LD) abstracted data from the remaining 15 articles. At least two authors abstracted 16 items from each article: study locations, sample sizes, type of cancers screened for, participants’ ages (including range, mean, and standard deviation), participants’ race and/or ethnicity, languages interpreted, type of patient navigators, study designs, recruitment methods, facility types, comparison groups, outcomes and results/major findings. One author (MG) reviewed all abstractions and registered any discrepancies between authors. These discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Quality Appraisal

The articles could not be combined to perform meta-analyses because of variations in the way the patient navigator interventions and outcomes were measured. All articles were systematically appraised.20–22 Randomized and nonrandomized quantitative studies were evaluated with the Downs and Black checklist. The Downs and Black checklist is a scoring algorithm which evaluates articles on reporting, external validity, bias, confounding, and power.23 For this review, the modified Downs and Black was used,24 which has a maximum score of 28. Previously defined categories from the literature were used to define the Downs and Black scores based on quality: 28–20: very good; 15–19: good; 11–14: fair; ≤10: poor).25,26

RESULTS

Figure 1 presents a PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating the systematic review process and the final 15 articles that were included in the narrative review. The 15 studies were subdivided according to type of cancer screening that was evaluated, including breast (combined with other cancers),27–31 colorectal cancer,32–44 and cervical cancer,45–47 represented in Table 1. Fifteen non-English languages were evaluated in these studies. Eight articles (53 %) were controlled trials; six of these were randomized28,33,35,37,41,44 and the remaining two were not.45,46 Seven (46 %) were cohort studies.27,29–31,39,43,47 . All the navigators in the studies assisted patients in navigating the cancer screening (e.g., setting up appointments and making reminder calls) along with providing language services.

Table 1.

Impact of Patient Navigators on Cancer Screenings.* Abbreviations: LEP Limited English Proficiency, RCT Randomized Control Trial, CT Control Trial, CS Cohort Study, w/ with, w/o without, PN Patient Navigator

| Author (Year), Location | N | Ethnicity and Language | Study Design | Intervention | Comparison Groups | Outcomes: Results Related to Patient Navigators Use (Statistical Analysis/Tests) | D&B Category (Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (and Other) Screening | |||||||

| Hoare (1994)28 | 527 | Pakistani and Bangladeshi; Punjabi and Bengali | RCT | Link worker (just educational aspect of PN services) | LEP persons w/PN vs. LEP persons w/o PN | No effect on screening There was no significant difference between the LEP women in the intervention group (49 %) and the control group (47 %) |

20 (very good) |

| Percac-Lima (2012)32 | 91 | Bosnian; Serbo-Croatian | CS | PN Services | Pre and Post Comparison of LEP Patients with PN | Increased screening rates At baseline, 44 % of Serbo-Croatian- speaking patients had received a mammogram. After one year follow-up, 67 % patients received mammograms while working with the PN (McNemar's Chi-square: p =0.001) |

16 (good) |

| Bell (1999)27 | 369 | Indian, Bengali; Arabic, Somali, Gujarati, Urdu, Bengali | CS | Letter from general practitioner, transportation, and language support from link worker | Pre and Post Comparison of LEP Patients with PN | Increased screening rates Mammography screening increased from 35.2 % to 50.7 % (15.5 % increase with CI 8.2–22.5). Language support was highly utilized and appreciated by the women. In the Somali Community, a Somali linker worker visited the community and of the 31 women visited, 12 (41 %) were screened |

11 (fair) |

| Percac-Lima, (2010)30 | 87,916 | Not reported | CS | PN Services for Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Scre ening | LEP persons w/PN vs. LEP persons w/o PN vs. English-speaking persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates Rates of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening were significantly higher among LEP patients in the Community Health Centers (CHC) with PN compared to CHCs without PN and non-CHC practices (p < 0.001) and compared to English speaking patients from non-CHCs (p < 0.05) |

18 (good) |

| Percac-Lima (2013)31 | 4274 | Black, Latino, Asian, Other/ Unknown White, Portuguese, Somali, Spanish, Russian, Farsi, Serbo-Croatian | CS | PN Services | Non-Spanish Speaking LEP persons w/PN vs. Spanish- and English-Speaking persons w/PN | Increased screening rates Over the four years of the intervention, non-Spanish speaking LEP persons’ screening rates increased from 64.1 % to 81.2 %, which was comparable to the Spanish-speaking patients (87.6 %, p = 0.07) and English-speaking patients (80.0 %; p = 66) |

19 (good) |

| Colorectal Cancer Screening | |||||||

| Lasser (2011)36 | 465 | Black, Latino; Creole, Portuguese, Spanish | RCT | PN Services | Intervention with LEP persons w/PN vs. control w/LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates One year after study entry, 33.6 % of intervention patients had been screened vs. 20.0 % of control patients (p = 0.001). Intervention patients contacted by PN were more likely to be screened than those who were unable to be contacted (39.9 % vs. 18.6 %, p < 0.001). Intervention patients received more colonoscopy procedures relative to controls (26.4 % vs. 13.0 %, p < 0.001). LEP patients in the intervention group were more likely to be screened that those in the control group (39.8 % vs. 18.6 %, p = < 0.001) |

25 (very good) |

| Percac-Lima, (2009)38 | 1223 | Black, Latino, Asian, Other not reported; Arabic, Portuguese, Somali, Spanish, Russian, Farsi, Serbo-Croatian | RCT | PN Services | Intervention w/ LEP persons w/PN vs. Control w/ LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates Intervention patients were more likely to undergo CRC screening than control patients (27 % vs. 12 %) for any CRC screening, p < 0.001; 21 % vs. 10 % for colonoscopy completion, p < 0.001). The PN intervention was more effective in English speakers. Overall screening rates (intervention and control) were higher for non-English speakers (19.5 % vs. 15.2 % (p = 0.05). |

24 (very good) |

| Christie (2008);34 | 21 | Black, Latino; Spanish | RCT | PN Services | Intervention w/LEP persons w/PN vs. Control w/ LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates Patients with navigators completed colonoscopies at higher rates that those without navigators (53.8 % vs. 13 %; p = 0.083). More patients in the control group refused colonoscopies than those in the intervention group (63 % vs. 23 %) |

13 (fair) |

| Spiegel (2009);40 | 779 | Latino; Spanish | CS | PN services and educational brochure | Pre and Post Comparison of LEP Patients with PN | Increased screening rates Prior to the intervention,, 457 patients were referred and 297 patients completed colonoscopy (completion rate 64.99 %, p < 0.001). After intervention, 322 patients were referred and 262 completed colonoscopy (completion rate 81.37 %, p < 0.001). After the intervention, increase in polyp detection, excellent and good bowl prep, and understanding of the procedure |

15 (good) |

| Jandorf (2005);42 | 78 | Latino; Spanish | RCT | PN Services | Intervention w/ LEP persons w/PN vs. Control group w/ LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates At the end of 3 months, 42 % of the intervention group had completed FOBT in comparison to 25 % in the control group (p = 0.086). At 3 months, 18.4 % in the intervention group had a colonoscopy appointment in comparison to none in the control group (p = 0.005) |

17 (good) |

| Percac-Lima (2014)44 | 47020 | Black, Latino, Asian, White, Other/ Unknown; Spanish, Serbo-Croatian, Others | CS | PN Services | LEP persons w/PN vs. LEP persons w/o PN; LEP persons w/PN vs. English-speaking person w/PN | Increased screening rates Over a 5-year period (2006–2010), LEP patients with PN increased screening rates at 7 % per year (p < 0.001). Before PN intervention LEP patients at both healthcare facilities had comparable screening rates (44.3 % vs. 44.7 %, p = 0.79), but after the implementation of the PN intervention LEP patients with PN had higher screening rates (70.6 % vs. 58.6 %, p = < 0.001). Prior to the intervention, LEP patients had lower screening rates compared to English-speaking patients (44.3 % vs. 52.6 %, p = < 0.001) but by 2010, there were no differences between the screening rates of LEP patients compared to English-speaking patients (70.6 % vs. 68 %, p = 0.09) |

17 (good) |

| Braschi (2014)45 | 392 | Latinos; Spanish | RCT | PN Services (Standard and Culturally Tailored) | English-speaking and LEP persons w/ Standard PN vs. English-speaking and LEP persons with Culturally Tailored Navigation | Increased screening rates In a comparison of two interventions, Culturally Tailored Navigation vs. Standard Navigation, there was no variability between interventions. In both interventions, participants with Spanish-speaking PN were more likely to complete screening than those navigated in either English or English and Spanish (86.1 % vs. 72.2 %, p = 0.001) |

21 (very good) |

| Cervical Cancer Screening | |||||||

| Wang (2010)47 | 134 | Chinese; Mandarin and Cantonese | CT | 2-hour education session and PN Services | Intervention w/LEP persons w/PN vs. control w/ LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates A greater percentage of LEP women with PNs (70 %) received screening compared to the control group (11.1 %), Χ2 = 59.46, p < 0.001 |

19 (good) |

| Fang (2007)46 | 102 | Korean; Korean | CT | 2-hour education session and PN Services | Intervention w/LEP persons w/PN vs. Control w/LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates Screening rates were significantly higher in the intervention group (83 %) compared with the control group (22 %), Χ2 = 41.22, p < 0.001. Seventy-five percent of the intervention group utilized the navigation services |

21 (very good) |

| Wasserman (2006)48 | 223 | Latino, Spanish | CS | PN Services | LEP persons w/PN vs. LEP persons w/o PN | Increased screening rates In a multivariate analysis, PNs, referred to as “promotoras”, were most effective in increasing probability of screening by 12.9 percentage points (p < 0.05) |

16 (good) |

Fourteen of the 15 quantitative studies demonstrated an increase in cancer screening rates for LEP patients. For breast cancer screening studies, there was a 17–25 % increase in screening services utilized in each study’s specific navigator interventions.27,30 Similarly, studies evaluating colorectal cancer screening saw a similar range in increase in screening services with LEP patients being 13–40 % more likely to utilized these preventive methods.33,35 Cervical cancer screening had the largest increase in service accesses, with one study showing a nearly 60 % difference between cervical cancer screening rates of Mandarin-and Cantonese-speaking patients with patient navigators and LEP patients without patient navigators.46 Only one study demonstrated no impact of navigation on breast cancer screening rates for Bengali or Pakistani women.28

Five of the studies described the level of training received by the patient navigators,30,31,35,37,43 which ranged from 6-hour trainings37 to 2-day workshops with an additional follow up training one year later.42 Two studies described their intervention personnel as “link workers” who primarily provided interpreting services and education on screening procedures.27,28 Educational interventions for LEP patients were coupled with navigation services in four studies,35,39,45,46 which included the use of translated materials, educational videos, workshops, and one-on-one educational sessions

The average Downs and Black score for quantitative articles was 17 (range 11–25, fair to very good), which has been categorized in previous literature as “good.”25,26 The range in scores was due to studies not controlling for confounders, study populations not being generalizable, not reporting adverse events, or small sample sizes. The spoken non-English language skills of the patient navigators were minimally reported in seven, as navigators were described as “bilingual,” either noted to be originally from a country where the target language was spoken, or the navigator’s ethnicity was used as an additional descriptor (i.e., “bilingual Hispanic woman”).27,31,35,37,39,41,43 None of the studies formally assessed the language skills of the patient navigators in English or the target language.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this systematic review of 15 studies suggest that patient navigators improve rates of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening for LEP patients. These findings align with previous systematic reviews that examined the impact of patient navigators on cancer screening rates in disadvantaged English-speaking patients.15,16 Patient navigators facilitated access to healthcare by identifying barriers and working with available resources to improve compliance with screening recommendations by clinicians.49 Since the enactment of the ACA, bilingual patient navigators are increasingly assisting newly insured LEP patients in navigating the healthcare system.17,49 Navigators played a dual role, not only navigating the newly reformed healthcare system, but also acting as interpreters of information. Future studies should investigate the impact of the ACA and bilingual patient navigators on access to care and cancer screening for previously uninsured LEP patients.

Despite the overall positive impact patient navigators have on screening rates, the variability of the study designs (e.g., cohort study verses randomized control trials) and quality of the studies made evaluating the true effect of patient navigators challenging. Many studies did not control for confounders, use study participants and study sites representative of the population of interest, report adverse events, or record actual p values. Of the eight controlled trials, two did not randomize participants and none were blinded. With regard to the interventions, most of the studies lacked information on the duration and content of the patient navigators’ training. Furthermore, there was great heterogeneity amongst the patient navigators’ trainings for the limited number of studies that reported them. It is possible that the screening rates were affected by the variability in the trainings, weakening the impact that the interventions had on cancer screening in the included studies.

An example of a model patient navigator training is the Integrated Cancer Care Access Network (ICCAN). ICCAN is a nationally recognized training program for linguistically and culturally diverse patient populations that have been diagnosed with cancer, and it has been using an extensive curriculum to train patient navigators since 2006. The patient navigator training includes modules on health care interpretation, and all patient navigators receive a certificate of completion for an intensive medical interpreter training.50 With the enactment of the ACA, the program has refined its curriculum to address the aspects of health care reform relevant to patient navigators. This program was not included in this review, as it is directed at patients already diagnosed with cancer and has not been extended to healthy populations receiving cancer screening. For the purposes of combining or reproducing data, it would be important for future studies to include a detailed description of patient navigator trainings used.

In addition to the lack of information on patient navigator training, none of the articles assessed the language skills of patient navigators who provided language assistance in the interventions. Appraisal of the language skills of patient navigators is important to ensure that they are fluent not only in the target language of the LEP population, but also in English,51 given that they are functioning as interpreters and need to provide accurate information to health care personnel. Although bilingual patient navigators are often from the same community as the LEP patients they work with and play many roles in the healthcare sphere, proficiency in English and the target language should not be assumed based on country of origin or ethnicity. Making this assumption is problematic because the term “native speaker” may have a different definition for people and language proficiency can be affected by many factors, including education in a non-English language and immigration history.52 The Clinician Cultural and Linguistic Assessment is the gold standard for testing clinicians’ non-English language skills.53 This exam is administered over the telephone and takes roughly one hour, is available 24 hours a day, and costs $100. A cheaper and more time-effective option is the clinically adapted Interagency Round Table (ILR). This self-report scale is free and has been shown to be highly reliable when comparing primary care physicians’ self-reported non-English language skills to their CCLA score.54 Trainings for patient navigators who will be working with LEP patients should include language skill assessments, such as the ILR, in both English and the target language, similar to what is done in well-designed training programs for professional interpreters.55 These trainings should be reported in future studies that look to evaluate the impact of patient navigators.

Further limitations aside from the identified evidence base described above include: all but two studies were conducted in the U.S., and the grey literature was not reviewed. With the studies under review all being conducted in Westernized cultures, there is a limit to the generalizability of the findings to other countries. Lastly, there is a potential for publication bias in our review, as we did not search the grey literature or unpublished studies.

Despite these limitations, this review has shown the importance of patient navigators for improving the cancer screening rates for LEP patients and has illuminated the gaps in the current research for future studies to fill. In the clinical setting, patient navigators should receive language-specific training and have their language skills evaluated to ensure they are prepared to assist patients. The cost of these trainings should be accounted for with grants and insurance companies, as the healthcare system has a legal (i.e., Civil Rights Act of 1964) and ethical obligation to provide LEP patients with quality care.56 Further, with the Affordable Care Act going into its third year of services, it is important that the navigation provided is evaluated to ensure LEP patients receive equal quality to their English-speaking counterparts.

CONCLUSIONS

The LEP population is increasing rapidly in the United States. Individuals with LEP face disparities in access to care and completion of cancer screening due to language barriers. While there was great variability in the interventions and how these patient navigators were evaluated, there was a 7–60 % increase in screening rates for LEP patients. These findings suggest that patient navigators may help reduce disparities in breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening faced by LEP patients. In order to collect useable data on the impact of language barriers and reduce disparities in care, it is essential to collect data on patient language needs and patient navigator language abilities in a systematic way.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 13 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the librarians at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for their assistance with this review, specifically Donna Gibson and Konstantina Matsoukas, and Marina Bluveshteyn for assisting with copy editing this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, A. FactFinder, Editor. U.S. Census Bureau 2011, US Census Bureau: American FactFinder.

- 2.Ryan, C., Languages in the United States: 2011, in American Community Survey Report. 2013, US Census Bureau.

- 3.LEP.gov. Commonly Asked Questions and Answers Regarding Limited English Proficient (LEP) Individuals. 2011; [cited 2015 Nov 23]; Available from: http://www.lep.gov/faqs/faqs.html#One_LEP_FAQ.

- 4.Fernandez A, et al. LLanguage barriers, physician-patient language concordance, and glycemic control among insured Latinos with diabetes: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Flores G, Abreu M, Tomany-Korman SC. Limited English proficiency, primary language at home, and disparities in children's health care: how language barriers are measured matters. Public Health Reports. 2005;120(4):418. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kandula NR, Lauderdale DS, Baker DW. Differences in self-reported health among Asians, Latinos, and non-Hispanic Whites: the role of language and nativity. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(3):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2002;47(2):80–96. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derose KP, Baker DW. Limited English proficiency and Latinos’ use of physician services. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57(1):76–91. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021–2028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiscella K, et al. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Medical Care. 2002;40(1):52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs EA, et al. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–1416. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandula NR, et al. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites. Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson E, et al. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3537–3540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paskett ED, Harrop J, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(4):237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells KJ, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Natale-Pereira A, et al. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3541–3550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schardt C, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2007;7(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review. 2005;62(3):255–299. doi: 10.1177/1077558705275416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs E, et al. The need for more research on language barriers in health care: a proposed research agenda. Milbank Quarterly. 2006;84(1):111–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karliner LS, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Services Research. 2007;42(2):727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehin R, Burnett R, Brasher P. Does the new generation of high-flex knee prostheses improve the post-operative range of movement? A meta-analysis. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume. 2010;92(10):1429–1434. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.23199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 suppl):101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell TS, et al. Interventions to improve uptake of breast screening in inner city Cardiff general practices with ethnic minority lists. Ethn Health. 1999;4(4):277–284. doi: 10.1080/13557859998056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoare T, et al. Can the uptake of breast screening by Asian women be increased? A randomized controlled trial of a linkworker intervention. J Public Health Med. 1994;16(2):179–185. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Percac-Lima S, et al. The impact of patient navigation on decreasing disparities in cancer screening in a large primary care network. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:S406–S407. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1450-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Percac-Lima S, et al. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1463–1468. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2491-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Percac-Lima S, et al. Patient navigation to improve breast cancer screening in Bosnian refugees and immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):727–730. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang JT, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening among culturally and linguistically diverse low-income patients—Does patient-provider language concordance matter? Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):S21. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christie J, et al. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inadomi JM, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening varies by race/ethnicity and screening strategy. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):S152. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lasser KE, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among ethnically diverse, low-income patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):906–912. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linsky A, et al. Patient-provider language concordance and colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):142–147. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1512-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Percac-Lima S, et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):211–217. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Stable EJ, Napoles A, Santoyo-Olsson J. Physician-patient communication and colorectal cancer screening among latino patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:S245. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1514-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiegel A, et al. Effect of a combined educational brochure and patient navigator on colonoscopy completion, polyp detection, bowel preparation, and patient education at an urban public hospital. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(5):A497. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu SP, et al. Promoting culturally appropriate colorectal cancer screening through a health educator - A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2006;107(5):959–966. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jandorf L, et al. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lasser K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of patient navigation to promote colorectal cancer screening in community health centers. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:S213. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Percac-Lima S, et al. The longitudinal impact of patient navigation on equity in colorectal cancer screening in a large primary care network. Cancer. 2014;120(13):2025–2031. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braschi CD, et al. Increasing colonoscopy screening for Latino Americans through a patient navigation model: a randomized clinical trial. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(5):934–940. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9848-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang CY, et al. A multifaceted intervention to increase cervical cancer screening among underserved Korean women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(6):1298–1302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, et al. Evidence-based intervention to reduce access barriers to cervical cancer screening among underserved Chinese American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(3):463–469. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasserman MR, et al. Social support among Latina immigrant women: bridge persons as mediators of cervical cancer screening. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(1):67–84. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-6343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen TU, et al. A qualitative assessment of community-based breast health navigation services for Southeast Asian women in Southern California: recommendations for developing a navigator training curriculum. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):87–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moy B, Chabner BA. Patient navigator programs, cancer disparities, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The Oncologist. 2011;16(7):926–929. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gany F, et al. Cancer portal project: a multidisciplinary approach to cancer care among Hispanic patients. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2011;7(1):31–38. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortier, J.P., H. AB, G., and C.G. Jacobs, Final Report: National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. . Washington, DC.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, OPHS, Office of Minority Health., 2001.

- 52.GROVE, E., et al. The importance of language assessment for bilingual staff in health services. in Conference Proceedings of Culture, Race and Community Making it work in the New Millennium. 1999.

- 53.Gayle Tang MSN, R., et al., The Kaiser Permanente Clinician Cultural and Linguistic Assessment Initiative: research and development in patient-provider language concordance. American journal of public health, 2011. 101(2): p. 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Diamond LC, et al. Does This Doctor Speak My Language?” Improving the Characterization of Physician Non‐English Language Skills. Health services research. 2012;47(1pt2):p. 556–p. 569. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez, J.a.F.G. PROMISE, Program for Medical Interpreting Services and Education in Eighth National Conference on Quality Health Care for Culturally Diverse Populations. 2013. Oakland, California.

- 56.Limited English Proficiency (LEP). Office of Civil Rights [cited 2015 Nov 23]; Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/civilrights/resources/specialtopics/lep/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)