Abstract

Breast cancer staging, in particular N-stage changed most significantly due to the advanced technique of sentinel lymph node biopsy two decades ago. Pathologists have more thoroughly examined and scrutinized sentinel lymph node and found increased number of small volume metastases. While pathologists use the strict criteria from the Tumor Lymph Node Metastasis (TNM) Classification, studies have shown poor reproducibility in the application of American Joint Committee on Cancer and International Union Against Cancer/TNM guidelines for sentinel lymph node classification in breast cancer. In this review article, a brief history of TNM with a focus on N-stage is described, followed by innate problems with the guidelines, and why pathologists may have difficulties in assessing lymph node metastases uniformly. Finally, clinical significance of isolated tumor cells, micrometastasis, and macrometastasis is described by reviewing historical retrospective data and significant prospective clinical trials.

Keywords: Sentinel lymph node, N-stage, Isolated tumor cells, Micrometastasis, Macrometastasis

The management and treatment of the axilla is moving towards conservatism since complete removal of axillary lymph nodes after sentinel lymph node (SLN) has not been affecting the overall survival and recurrence free survival. SLN biopsy has been as effective as axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in staging, locoregional control and survival without morbidity such as lymphedema and swelling. Along with the advancement of SLN biopsy, pathologists have been scrutinizing assessment of SLN findings. Finding metastatic carcinoma in lymph nodes is a statistical exercise of probability. With more levels of blocks with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical (IHC) stain sections we get, the probability of having positive lymph node increases. Pathologists have developed a robust way of detecting metastasis in SLN. In fact, with the application of IHC stain, negative SLN by a single level routine H&E slide can convert into positive SLN in 12%–29% [1-6], most of them with small volume metastases such as isolated tumor cells (ITC) and micrometastasis, which are staged as pN0(i+) and pN1mi.

With the advent of detecting increasing number of small volume metastases in SLN, the following questions arose: Is ITC a true metastasis? What is the chance of having positive metastatic lymph node when complete ALND is done with ITC in? Why is ITC considered pN0(i+) and not counted as a positive lymph node in Tumor Lymph Node Metastasis (TNM) staging? For that matter, is micrometastasis clinically significant metastasis? What is the chance of having positive metastatic lymph node when complete ALND is done? Why micrometastasis is considered pN1mi and counted as a positive lymph node in TNM staging? Is the volume or the number of tumor cells between ITC and micrometastasis so different that we should count as negative and positive in the N-stage respectively? Who should decide the cut-off number or size/volume of metastatic cells between pN0(i+) and pN1mi? Why was complete ALND recommend for pN1mi and macrometastasis in SLN but not for pN0 (i+) traditionally? Are we (pathologists) uniformly and correctly assigning pN0(i+), pN1mi and macrometastasis in SLN? And even if we have accomplished such tasks successfully, is it clinically meaningful, and helpful to breast cancer patients in understanding prognosis? Lymph node staging is the most important prognostic factor for breast cancer. Is this still true? With numerous clinical trials published in literature suggesting that conservative management is currently more appropriate regardless of the size of metastasis in SLN, do we still need to split our hairs dividing pN0(i+), pN1mi and pN1 in N-stage?

In this article, review of SLN in breast cancer is listed in the following order: Brief history of SLN staging, problems in determining metastatic SLN size in pathology, clinical significance of positive SLN, along with personal commentary and a plea to use evidence based practice to develop new and relevant standard criteria in SLN in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) staging systems.

BRIEF HISTORY OF SENTINEL LYMPH NODE STAGING

The TNM staging system was initially devised more than 50 years ago by Pierre Denoix in France [7]. From then on, many revisions were made in advent of changes in breast cancer management and treatment.

In 1987, the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and the AJCC staging systems were unified into a single TNM staging system to be able to communicate clinical information without ambiguity. “T is for the size or direct extent of the primary tumor, N is for the spread of regional lymph nodes and M is for the presence of distant metastasis.” Since the first publication in 1977, currently AJCC/UICC system revised and published the 7th edition [8,9].

It is arguable that N part of the staging changed most significantly since the SLN, biopsy first described by Giuliano et al. [10] in 1994 in breast cancer as a potential altering the role of ALND by using intraoperative lymphatic mapping.

Along with SLN biopsy advancement by surgical oncologists, pathology assessment of SLN biopsy sample led to significant changes in N-stage by the AJCC Staging Manual. Starting from the 5th edition in 1997 when the first SLN was reported, the 6th edition in 2003 and the 7th edition in 2010 had some changes regarding SLN reporting. As SLN biopsy became more a standard treatment in the management of breast cancer, the AJCC Staging Manual needed revision to reflect the continual development and knowledge in this field. The 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual when compared to the previous one contains some of the most extensive and significant revisions pertaining to SLN related to the growing knowledge of new technology such as IHC staining and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The principal changes are related to the size, number, location, and method of detection of regional metastases to the lymph nodes. A Breast Task Force was constituted to serve in an advisory role to the AJCC in the fall of 2001 and the 6th edition reflected the significant changes. The Breast Task Force used the guideline to recommend changes and additions based on evidence-based findings in published clinical outcome data, reflecting a wide-spread clinical consensus and changes in nomenclature and coding system which support the uniform accrual of outcome information in national databanks [11,12].

In the AJCC 5th edition, micrometastases were defined as metastatic lesions no larger than 2 mm in greatest dimension and classified as pN1. The terminology “occult metastases” was interchangeably used to describe a small metastatic carcinoma in the lymph node in the literature. The upper limit of 2 mm cut-off for separating micro- and macrometastases was determined by two studies 30 years ago [13,14].

The major change in the AJCC 6th edition was to define the lower limit for micrometastasis defined as a metastatic lesion larger than 0.2 mm in diameter and the upper limit was kept in 2 mm and ITC (single cells or cell deposits) no larger than 0.2 mm and classified as pN0. This lower limit of >0.2 mm (10 times smaller than the upper limit) had been tested in only one retrospective study [15].

With the advent of more sensitive technique, such as IHC stains, it was easier to detect ITC that were not readily visible from the H&E stain slides which was the gold standard for detection of metastatic carcinoma in the axillary lymph nodes. For example, when H&E stain shows no metastatic carcinoma but IHC stain with ITC, then the classifier became pN0(i+) for positive IHC, no cluster >0.2 mm. The designation of pN1mi (i+) was used when H&E stain negative but IHC stain detected micrometastasis. So, “i” stands for IHC stain in the 6th edition AJCC [16].

Separating the upper and lower limits of cutoff for ITC and micrometastatic lymph node is not an easy task since there is no “pure” study that has evaluated differences in overall survival compounding factors such as with or without tumor size, chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

The pN0(mol-) and pN0(mol+) classifiers were also added in the 6th edition of AJCC based on the molecular findings using RT-PCR.

The additional designation of (sn) for “sentinel node” was used in the classification of TNM staging system when only the SLN was excised without the full ALND. See Table 1.

Table 1.

AJCC 6th edition

| pN0 (sn) | No metastasis-sentinel lymph node |

| pN0 (i+) | Isolated tumor cells (single cells or cell deposits) no larger than 0.2 mm |

| pN1mi | Metastatic lesion larger than 0.2–2.0 mm |

| pN1mi (i+) | H&E stain negative but IHC stain detected micrometastasis |

| pN0 (mol-) | Negative molecular findings using RT-PCR |

| pN0 (mol+) | Positive molecular findings using RT-PCR |

AJCC, American Joint Committee of Cancer; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immunohistochemical; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

With the advent of SLN biopsy, knowing sentinel nodes are more likely to contain metastases than non-SLNs, pathologists began to perform much more thorough and comprehensive examinations which included grossing by submitting the entire node by sectioning 2.0 mm thickness in a longest axis, serial sections for H&E stains instead of just one section, and adding IHC stains which deviated from the reference population assay in which lymph node examination was much simpler- one H&E section per node for pathologic examination before 1990s. Previously, grossly negative large lymph nodes were not necessarily entirely submitted for histologic examination.

Introduction of ITC was to prevent overtreatment of low-volume nodal involvement since some of the ITC is caused by passive tumor cell transport to the SLN after pre-operative fine needle aspiration (FNA) and/or core needle biopsy procedures and iatrogenic displacement due to breast massage causing benign epithelial elements in lymph node resulting false positive especially in papillary lesions [17].

As we all know, finding metastatic carcinoma in lymph nodes is a statistical exercise of probability. With more H&E and IHC stain sections we get from the block, the probability of having positive node increases. We have the capability to detect even one cell in the SLN if this is clinically meaningful but first, we need to figure out whether this effort is paid off by clinical significance.

Also, there are differences in terminology in literature. Prior to AJCC 2003 and 2006, the term “isolated tumor cells” and “micrometastasis” were not clearly defined. Some studies referred to these as “occult metastasis.”

Later on the AJCC definition of SLN tumor deposits were measured using a micrometer and placed in one of three categories [9]: macrometastasis, micrometastasis, or ITC. A macrometastasis was classified as “one or more tumor deposits greater than 2 mm.” A micrometastasis was classified as a tumor deposit “greater than 0.2 mm but not greater than 2.0 mm in largest dimension.” ITC were “defined as single cells or small cluster of cells not greater than 0.2 mm in largest dimension.” A cluster was defined as “a confluent focus of tumor cells touching other tumor cells.” The single largest cluster was measured by micrometer. Single dispersed cells throughout the lymph node were regarded as ITC if the largest cluster measured less than or equal to 0.2 mm [9]. The presence of metastatic disease is measured by the size of the largest contiguous metastasis for multiple foci in SLN. The main differences between the AJCC 6th edition to the AJCC 7th edition in regards to SLN is to count the number of metastatic cells; if it is less than 200 cells versus over 200 cells for ITC and micrometastasis respectively. The label “i” stands for isolated tumor cells and not IHC stain for the 7th edition AJCC.

The main reason for a 200 cell cutoff was to have better reproducibility between pathologists. The arbitrary cutoff of the exact size and number was listed for improvement of agreement between pathologists without any clinical trial of the significance in prognosis and clinical validation. In fact, this was incorporated into the 7th edition for large dishesive, non-confluent tumor cells throughout the lymph node typically seen in metastatic lobular carcinoma. In addition, the 7th edition of AJCC states “these thresholds are meant to be guidelines, and not absolute cutoffs, to help pathologists determine if the tumor burden in a given lymph nodes is likely to be clinically important or not. The pathologist should use judgment and not an absolute cut-off of 0.2 mm or exact 200 cells, in determining the likelihood of whether the cluster of cells is an ITC or a true micrometastasis”. See Table 2.

Table 2.

AJCC 7th edition

| pN0 (i+) | Isolated tumor cells (single cells or cell deposits) no larger than 0.2 mm or fewer than 200 cells |

| pN1mi | Metastasis greater than 0.2 mm and/or more than 200 cells, but none greater than 2.0 mm |

| pN1a | Macrometastasis in 1 to 3 axillary lymph nodes, at least 1 metastasis greater than 2.0 mm |

| pN2a | Metastases in 4 to 9 axillary lymph nodes (at least 1 tumor deposit greater than 2.0 mm) |

| pN3a | Metastases in 10 or more axillary lymph nodes (at least 1 tumor deposit greater than 2.0 mm) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee of Cancer.

According to the 7th edition AJCC, a positive node is defined as a metastasis measuring at least 0.2 mm, or >200 tumor cells (pN1mi). Whenever there is a positive lymph node, the pathologist also needs to describe the following: the size of metastasis (or number of tumor cells), the anatomical node involved such as axilla, internal mammary, intramammary, infraclavicular or supraclavicular lymph node, the total number of positive nodes, and the method of detection such as clinical, FNA or tissue biopsy.

Positive intramammary lymph nodes are count in the total axillary lymph node count. Positive internal mammary SLN affects pN stage depending on status of other nodes (metastasis in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary lymph nodes in the presence of 1 or more positive axillary lymph nodes; or in more than 3 axillary lymph nodes and in internal mammary nodes with microscopic disease detected by SLN dissection but not clinically apparent). Positive infraclavicular node is staged as pN3a and supraclavicular node is staged as pN3c.

In addition, there is a troubling statement in the AJCC 2010 “Data elements with asterisks (small clusters of cells not greater than 0.2 mm or single tumor cells, or a cluster of fewer than 200 cells in a single histologic cross-section) are not required. However, these elements may be clinically important but are not yet validated or regularly used in patient management.”

Further disclaimer statements in the 7th edition of AJCC are as follows: “Approximately 1,000 tumor cells are contained in a 3-dimensional 0.2-mm cluster. Thus, if more than 200 individual tumor cells are identified as single dispersed tumor cells or as a nearly confluent elliptical or spherical focus in a single histologic section of a lymph node, there is a high probability that more than 1,000 cells are present in the node. In these situations, the node should be classified as containing a micrometastasis (pN1mi). Cells in different lymph node cross sections or longitudinal sections or levels of the block are not added together; the 200 cells must be in a single node profile even if the node has been thinly sectioned into multiple slices. It is recognized that there is substantial overlap between the upper limit of the ITC and the lower limit of the micrometastasis categories because of inherent limitations in pathologic nodal evaluation and detection of minimal tumor burden in lymph nodes. Thus, the threshold of 200 cells in a single cross-section is a guideline to help pathologists distinguish between these 2 categories [9].” And final statement is as follows: “The pathologist should use judgment regarding whether it is likely that the cluster of cells represents a true micrometastasis or is simply a small group of isolated tumor cells.”

In 2010, both the UICC and TNM joined in the provision in guidelines for SLN classification, however, studies have shown poor reproducibility in the application of in both invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinomas.

Furthermore, previous studies have shown that application of IHC stain on H&E negative lymph node can detect small volume metastatic carcinoma in 12%–29% of cases. However, all the previous data of prognosis based on lymph node status has been from one H&E section evaluation. Therefore due to more thorough examination of SLN, more cases of ITC have been reported [1-6].

For this reason, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) published a consensus statement in July 2000 recommending a single H&E slide section from each lymph node block without gross evidence of metastasis without routine cytokeratin IHC stain or routine serial sectioning based on the preliminary study from John Wayne Cancer Center which found no differences in five-year disease-free survival rate between node negative by H&E negative, IHC negative versus H&E negative, IHC positive groups [18-20].

Although CAP guidelines and recommendations for SLN biopsy for pathologists did not include serial sectioning with multiple H&E slides and IHC stains, many pathologists reported and continued to perform comprehensive evaluation on SLN including our institution to this date. With the advent of the comprehensive SLN evaluation, probability of finding small metastasis increased and the natural question is whether to perform completion ALND on these cases. It is reported that among patients with a positive SLN by H&E stain were found to have additional nodal metastasis in ALND in 48.3% of cases [21]. In addition, metastatic carcinoma is found in non-sentinel nodes during ALND in 9%–15% and 15%–35% of patients with ITC and micrometastasis in the SLN respectively [22-25].

Traditionally, complete ALND was done for SLN with pN1mi and macrometastasis but not for pN0(i+). Also adjuvant chemotherapy may have been added to pN1mi and macrometastasis. This was true in many practices including our institution. And therefore, it would be important to distinguish an accurate size of metastatic tumor deposits in the SLN.

PROBLEMS IN DETERMINING METASTATIC SENTINEL LYMPH NODE SIZE IN PATHOLOGY

Grossing axillary SLN

How best to gross SLN is not stated in the AJCC Staging Manuals. Most pathologists submit clinically negative SLN entirely for microscopic examination by slicing lymph node in a longest axis into 0.2 cm thickness based on CAP guideline. CAP states that a single H&E section from each block is sufficient and multiple level sections and IHC stain for keratin are not necessary. However, there are many institutions performing multiple levels and IHC stains for each block for SLN. The “correct” method is still a matter of debate. In our institution, we get 3 multiple levels for H&E stain and 2 intervening keratin IHC stains for entirely submitted each SLN blocks. The reason for this is that IHC stain highlights small metastatic cells easier than H&E stain, especially for the metastatic lobular carcinoma cases.

Microscopic examination of SLN

While the 7th edition AJCC criteria and definition are fairly straightforward, its’ application may be difficult in reality for pathologists to uniformly classify N-stage correctly. Initially, in 2006, Dr. Connolly [26] described some of the most practical challenges in the classification in the assessment of SLN biopsy separating ITC, micrometastases, and macrometastases.

Cserni et al. [27] reported that there is 24% discordance in their review of 512 cases of low-volume nodal metastasis and a plea for better formulated supplemented TNM definition.

Literature reported the kappa values for pathologist’s agreement is at best moderate to substantial reproducibility [28-32]. The kappa value for interobserver agreement was reported moderate (0.55 and 0.56) for pN0(i+) and substantial (0.62) for pN1mi. This is an improvement from the previous interobserver agreement amongst expert breast pathologists (kappa: 0.49) and community hospital-based pathologists (kappa: 0.47) based on European Working Group for Breast Screening Pathology (EWGBSP). Despite the intent for the better interpretation of metastatic tumor cells in lymph node in the 7th edition AJCC, many issues have not been resolved. In 2012, Netherlands group published the discrepancy rate between central to local pathologists in which changed pN status in 24% with kappa value of 0.69 [33].

This is stating that one of four cases in breast cancer, pathologists do not agree with N-stage even though the descriptor for N-stage is easily understandable in the AJCC Staging Manual. There are still some circumstances pathologists have difficulties knowing how to accurately assign N- stage based on the 7th edition AJCC. Here are some of the examples:

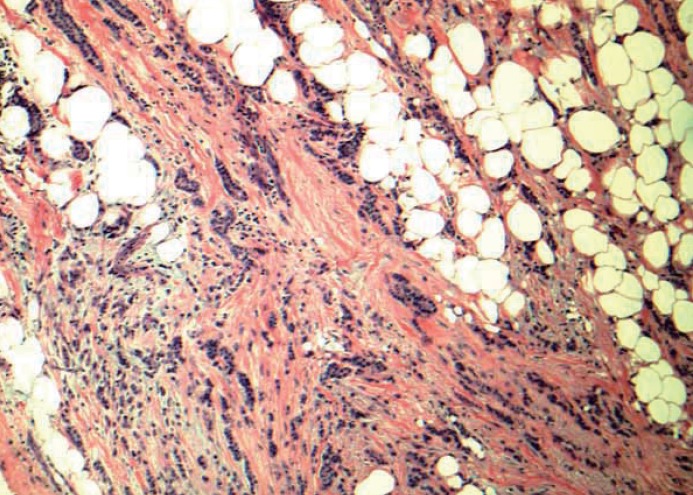

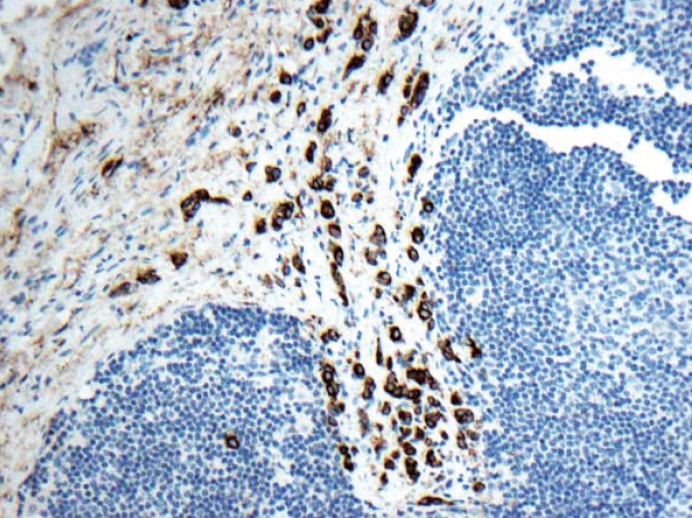

1. Multiple discontinuous foci of metastatic carcinoma as seen in Figs. 1 and 2. The entire area of metastatic carcinoma is >2 mm but the largest contiguous metastatic carcinoma measures <0.2 mm. Is this macrometastasis or micrometastasis? The AJCC staging criteria states that we should not add these noncontiguous metastatic foci but shouldn’t there be an upper limit to number of foci of micrometastases to upgrade to macrometastasis based on the sheer volume of tumor deposits? Does this actually make a common sense to classify as pN1mi? All the other organs in pathology staging would classify this kind of scenario as “metastatic carcinoma.” Using the best pathologist’s “judgment,” macrometastasis may be best for this case although by strict criteria, it is pN1mi.

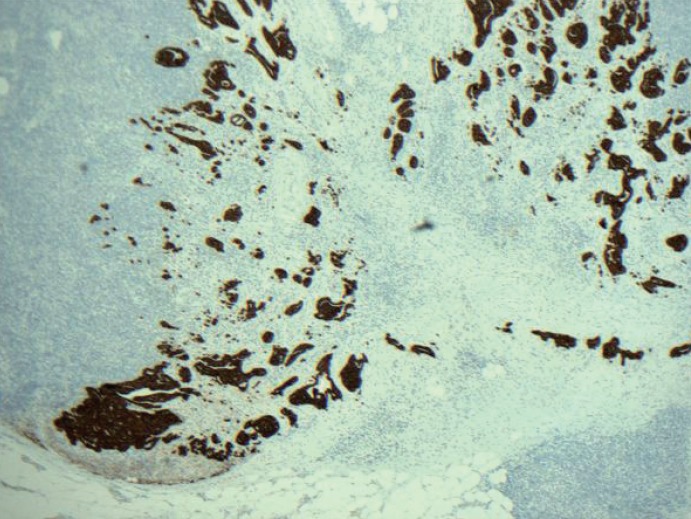

Fig. 1.

Keratin immunohistochemical stain. Multiple discontinuous foci of keratin positive metastatic tumor deposits are noted. The largest cluster seen on the lower left corner is < 2 mm. Is this macrometastasis or micrometastasis? The American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria states that we should not add these non-contiguous metastatic foci but shouldn’t there be an upper limit to number of foci of micrometastases to upgrade to macrometastasis based on the sheer volume of tumor deposits? Does this actually make common sense to classify as pN1mi as the criteria written in the 7th edition AJCC? All the other organs in pathological N staging would classify this kind of scenario as “metastatic carcinoma.”

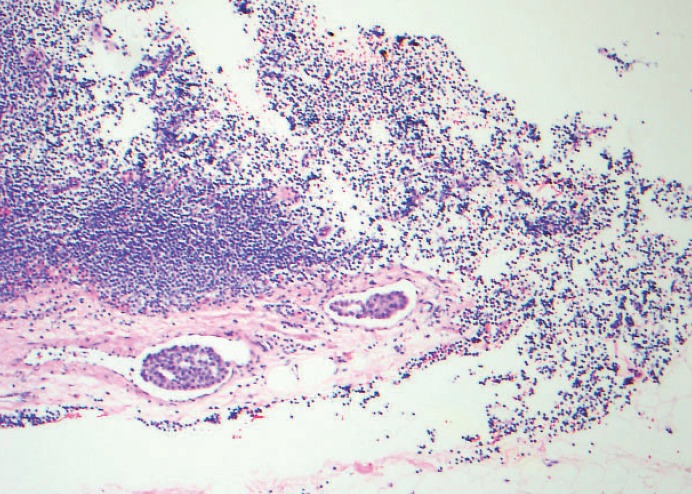

Fig. 2.

Keratin immunohistochemical stain. Most pathologists would classify this image as macrometastatic lymph node but technically each cluster or group of cells are not touching each other in a confluent or contiguously, and therefore, each cluster should be considered independent and measured independently.

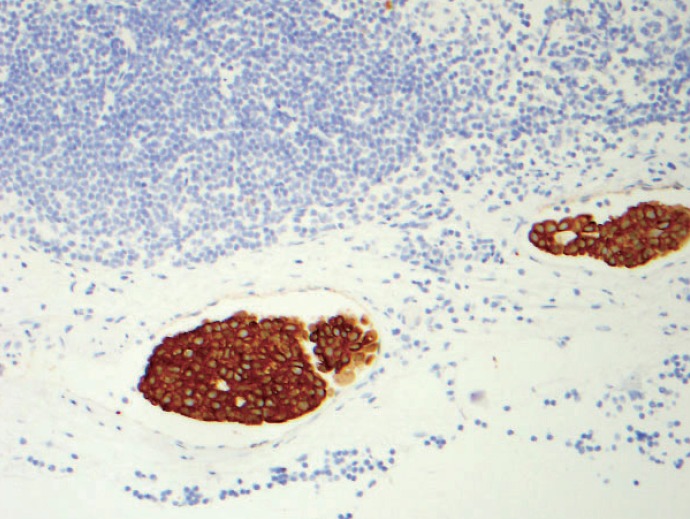

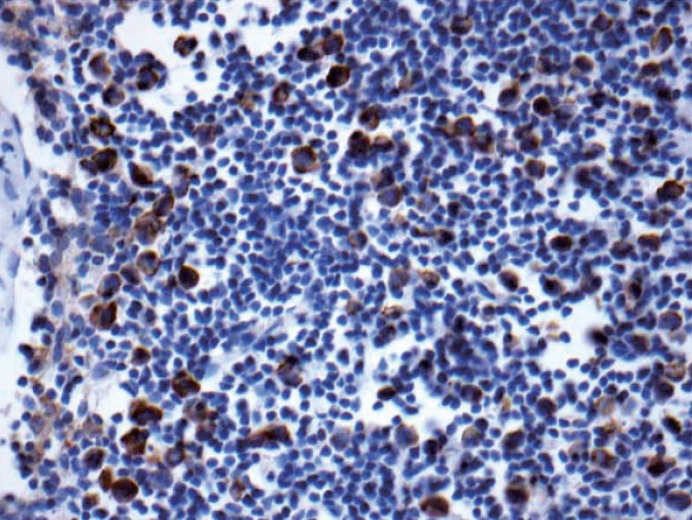

2. Multiple discontinuous foci of metastatic carcinoma as seen in Fig. 3. The entire area will be classified as micrometastasis but one of the longest contiguous areas will be classified as ITC. Counting the number of metastatic carcinoma may be < 200 cells. Is this micrometastasis (pN1mi) or ITC [pN0(i+)]? How should we best judge?

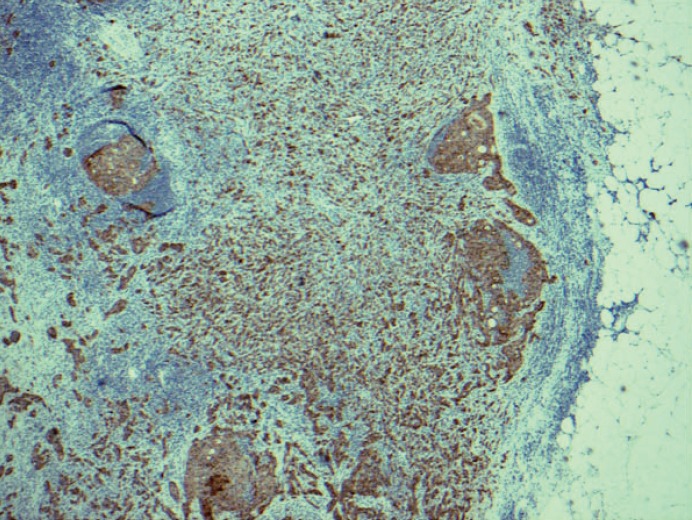

Fig. 3.

Keratin immunohistochemical stain. Multiple discontinuous foci of metastatic carcinoma each cluster measuring no larger than 0.2 mm and fewer than 200 cells. Is this micrometastasis (pN1mi) or isolated tumor cells [pN0(i+)]? There is even extracapsular invasion seen on the upper left corner.

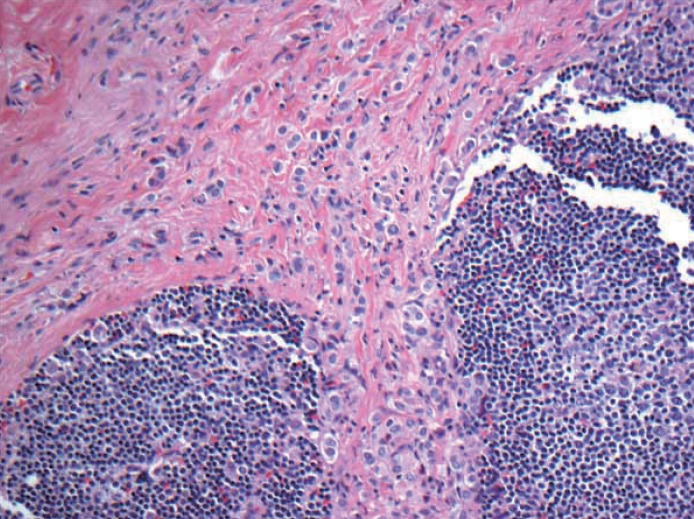

3. Metastatic carcinoma seen in axillary adipose or fibrous tissue without any residual and apparent lymph node structure. Should this be counted as positive lymph node or a carcinoma arising in axillary breast tissue? Based on the 6th edition, cancerous nodules in the axillary fat without evidence of residual lymph node tissue should be classified as positive axillary lymph nodes. But what if these cancerous nodules in the axilla are cancer cells from the axillary breast tissue? Should it be classified as extensive extracapsular extension? Many pathologists do not classify cancerous nodules in axilla without apparent lymph node structure as lymph node metastasis (unpublished personal observation). The dimension of the tumor from this scenario may end up in T-stage rather than in N-stage. See Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Low grade invasive tumor is seen from axillary fat without adjacent residual and apparent lymph node structure. Should this be counted as positive lymph node or a carcinoma arising in axillary breast tissue? Based on the 6th edition, cancerous nodules in the axillary fat without evidence of residual lymph node tissue should be classified as positive axillary lymph nodes. There is no normal breast tissue or ductal carcinoma in situ around this tumor. Is this axillary breast tissue with carcinoma, totally effaced lymph node with metastatic carcinoma or extensive extracapsular invasion? Many pathologists do not classify cancerous nodules in axilla as lymph node metastases.

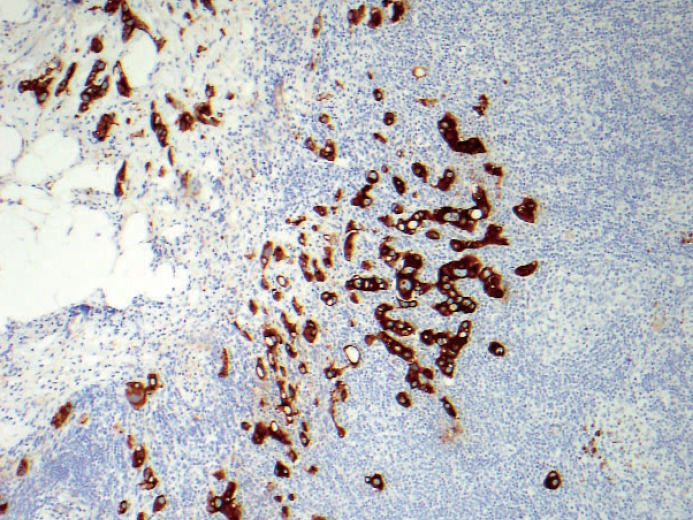

4. When there is pericapsular lymph-vascular invasion (LVI) in which tumor cells are not in the parenchyma or subcapsular part of lymph node, is that considered metastatic or LVI? Deeper sections still did not show intracapsular or intraparenchymal involvement. Anecdotally, this kind of the case was sent out to other breast pathology experts and came back with different opinions; some considered metastatic carcinoma pN0(i+) or pN1mi depending on the size of the largest contiguous dimension of metastatic focus and some just LVI. See Figs. 5 and 6. Based on CAP guidelines, capsular LVI is considered metastatic carcinoma and the largest dimension is measured as the size of metastasis. However the 7th edition AJCC does not specify this scenario.

Fig. 5.

Pericapsular lymph-vascular invasion (LVI) in which tumor cells is not seen in the parenchyma or subcapsular part of lymph node. Should this be classified as metastatic [either pN0(i+) or pN1mi depending on the maximum linear dimension] or LVI? Tumor deposits seen in afferent vessel and not intracapsular or intraparenchymal involvement is technically LVI, a transient step before metastasis into lymph node. Based on College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines, capsular LVI is considered metastatic carcinoma and the largest dimension is measured as the size of metastasis. However the 7th edition American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) does not specify this scenario.

Fig. 6.

Keratin stain from the same case as Fig. 5.

5. When most of the metastatic carcinoma is seen outside the lymph node capsule (in this case by metastatic lobular carcinoma) with only one ITC within the lymph node parenchyma, is it considered extracapsular invasion with ITC or is it micrometastasis based on the total number of cells of >200 or >0.2 mm? See Figs. 7 and 8. Should the extracapsular extension be included as a maximum linear dimension of metastasis?

Fig. 7.

Metastatic lobular carcinoma is seen mostly outside the lymph node capsule with only one isolated tumor cell within the lymph node parenchyma. Should the extracapsular extension included as maximum linear dimension of metastasis or is it considered extracapsular invasion with isolated tumor cells?

Fig. 8.

Keratin stain from the same case as Fig. 7.

6. Matted lymph nodes with metastatic carcinoma; how should we count? One matted lymph node or identifiable apparent lymph nodes involved with metastatic tumor? This may alter pN1a or above in some cases.

7. Invasive lobular carcinoma often has loss of E-cadherin which results in individual cell pattern in both breast and lymph node. This scenario was written by Turner et al. [30] who reported inconsistence in nodal metastases by breast pathologists with the initial kappa before the training program was 0.575 and post-test was 0.947. We reported that strict adherence of the 6th edition AJCC criteria will result in down staging N in many lobular carcinoma cases [34].

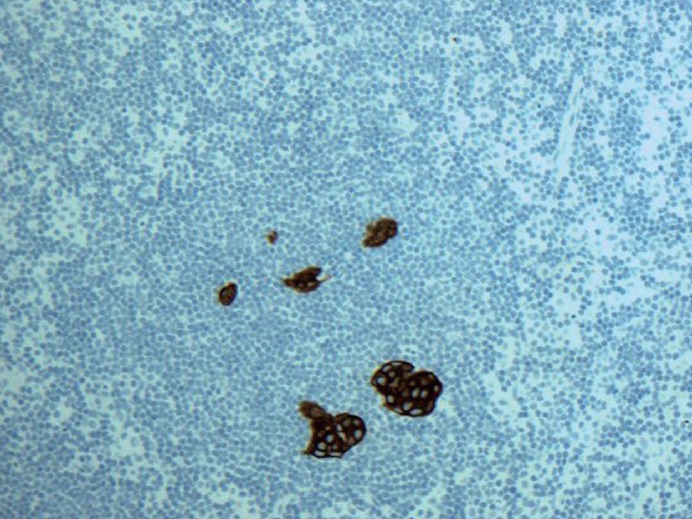

The 7th edition AJCC was bit more helpful in this situation because one needs to count the number of metastatic cells in SLN; if it is less than 200 cells versus over 200 cells for isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis respectively. However, the number 200 cells is arbitrarily chosen without any background published research data with clinical follow-up. Although some metastatic lobular carcinoma cases have obvious macrometastasis, diffuse single or few cell clusters of infiltrating pattern is typical for invasive lobular carcinoma metastatic to lymph node (Fig. 9). All cases such as this will be classified as pN1mi based on >200 cells but why can’t it be macrometastasis? Is there an upper limit such as 500 cells or 1,000 cells to qualify as macrometastasis?

Fig. 9.

Keratin stain. Dispersed pattern of multiple and numerous foci metastatic lobular carcinoma to lymph node is commonly seen. If these cells are more than 200 cells or less than 200 cells, then, it is classified as micrometastasis (pN1mi) and ITC [pN0(i+)] respectively. All cases such as this will be classified as pN1mi based on > 200 cells but why can’t it be macrometastasis? Is there an upper limit such as 500 cells or 1,000 cells to qualify as macrometastasis?

8. For N-stage, if there is stromal desmoplasia or stromal proliferation around small volume metastasis, the 6th edition AJCC states that the size of the tumor deposit should include the stromal reaction. The 7th edition AJCC recognized that this distinction is highly subjective. In general, after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the classification of lymph nodes should be the same as the patients who did not have neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Lymph nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy more frequently show stromal fibrosis without “typical desmoplasia,” foamy histiocytes with multinucleated giant cell reaction, elastosis and small clusters of non-confluent residual and viable metastatic tumor cells. How should we classified- is this ypN0 (i+) or ypN1? After all, even small residual metastatic deposits after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is probably not true ITC but a remnant of macrometastasis prior to therapy and hence, it should be classified as pN1. Currently, the AJCC Staging Manual is not clear about this scenario and hence, pathologists are stating in their report how they measured the size of metastatic deposit with a long explanation.

9. Location of metastatic tumor cells whether it is subcapsular or intraparenchymal is not specified in the 7th edition AJCC, however, many European pathologists based on previous UICC related publications, tumor cells located within the parenchyma measuring even less than 0.2 mm is considered micrometastasis and not considered as ITC. Regardless of the location, most of American pathologists would consider ITC purely depending on the size of metastasis. See Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Keratin stain. Isolated tumor cells are seen (< 200) within the parenchyma of the lymph node. Most American pathologists will classify this is pN0(i+) but many of European pathologists may classify this as micrometastasis based on previous International Union Against Cancer (UICC) related publications.

The above stated scenarios are difficult to resolve and ultimately depends on the pathologists to make appropriate judgments resulting high subjectivity and inconsistence in N-stage. Finally, we need to ask ourselves, is this distinction between pN0 (i+) and pN1mi useful for patient’s prognosis, treatment plans and overall survival? For that matter, is macrometastasis different in prognosis and overall survival when compared to pN0(i+) and pN1mi? Our goal is to determine the significance of these findings, albeit that there is difficulty in interobserver reproducibility among the pathologists. Also we should keep in mind that both retrospective and prospective studies in literature composed of variability in interpretation of N-stages; pN0(i+), pN1mi and pN1a even with the best intention of adhering to AJCC criterion. Also the mode of detection of metastatic SLN has been different in literature.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF SENTINEL LYMPH NODE

In 2005, an American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline recommendation for SLN biopsy in early-breast cancer was published. The recommendation and guideline were based on the literature review from one prospective randomized controlled trial, four limited meta-analysis, 69 published single-institution and multicenter trials. SLN biopsy alone without complete ALND is considered standard of care for SLN negative patients. Completion ALND was standard treatment for patients who had macro- and micrometastasis in SLN for T1 and T2 tumors. “For large or locally advanced inflammatory breast cancer (T3 and T4), ductal carcinoma in situ, when breast-conserving surgery is to be done, pregnancy, in the setting of prior non-oncologic breast surgery or axillary surgery, and in the presence of clinically suspicious axillary lymph node, SLN biopsy was not recommended [35].”

Survival data on pN0(i+), pN1mi and pN1 showed mixed results. Survival benefit of preforming ALND after ITC and/or micrometastasis in SLN was not clear cut. Some reported an adverse effect on survival and others have shown no effect. Again, the mixed results may have been due to the variable definitions of micrometastases and ITC in literature and different mode of detection.

Retrospective clinical data

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database reported that micrometastasis represents a significant prognostic marker. Their data consists of 209,720 patient numbers between 1992 and 2003 and the 10 year survival among pN1, pN1mi and pN0(i+) is 73%, 77%, and 78%, respectively. Also, N1mi diagnoses increased from 2.3% to 7% [36].

de Boer et al. [37] published MIRROR (Micrometastasis and Isolated Tumor Cells: Relevant and Robust Or Rubbish?) study in Netherlands which included three cohorts with the median follow-up of 5.1 years: 865 patient with negative regional lymph nodes who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, 865 patients with either ITC or micrometastasis in lymph nodes who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy and 994 with either ITC or micrometastasis in lymph nodes who did receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The authors found ITC or micrometastases in regional lymph nodes were associated with a reduced disease-free survival who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy and those who received adjuvant chemotherapy had improved disease-free survival rate [37].

Pugliese et al. [38] studied a total of 954 SLN biopsies consist of 491 N0(i-), 86 N0(i+), 73 N1mi, 146 N1a, 29 N2a, and 11 N3a patients with a median follow-up of 45.4 months and found no differences in overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) between pN0(i-) and pN0(i+) or pN1mi but worse prognosis was noted when the size of the metastases reached the pN1a.

Hansen et al. [39] reported no difference in disease-free survival and OS with a median follow up of 8 years between pN0, pN0 (i+) and pN1mi in their study cohort of 790 with patients. Their cohort consisted >90% who had received adjuvant chemotherapy. Only patients with macrometastasis had a statistical significant decrease in disease-free survival and OS.

Bilimoria et al. [40] reported a retrospective study from the National Cancer Data Base on 97,314 SLN positive patients from1998–2006 subdivided into those who had ALND and those who did not have ALND had a similar axillary local recurrence and 5 year relative survival; 23% macrometastases (pN1) and 55% with SLN micrometastases (pN1mi).

The SEER Database by Yi et al. [41] reported a total of 26,986 composed of 11% pN1 and 33% pN1mi from 1998–2004 had no difference in OS at a median follow-up of 50 months.

In addition, there are nine smaller studies comprising a total of 1,035 patients with positive SLN without ALND and reported low axillary local recurrence rate, in the range of 0% to 2% at 28–82 months follow-up [42].

Our institution also supported that SLN biopsy alone as adequate intervention in 302 patients with an average clinical follow-up of 24 months [43]. Even for the mastectomy cases with pN1 disease in SLN did not affect OS and RFS between the radiation therapy without ALND and complete ALND surgery [44].

Prospective clinical data

There are three significant prospective randomized studies relevant to SLN metastasis: the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) trial-32, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) trial Z0011, and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG 23-01) [45-47].

The NSABP B-32 was a randomized controlled phase 3 trial composed of 5,611 patient sample divided into group 1 (SLN and ALND) and group 2 (SLN alone if no metastasis SLN with ALND if metastatic carcinoma was present in SLN). The adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy was relatively equally divided in between these groups: 85% in group 1 and 84.1% in group 2. The clinical follow-up was 95.6 months and the endpoint was overall survival. The authors found no differences in OS, disease-free survival and regional control between two groups. NSABP B-32 also looked into clinical significance in “occult metastasis” comparing pN0, pN0(i+) and pN1mi groups and found no difference in overall survival among these groups during 5-year follow-up period. The authors concluded that additional evaluation including IHC stains and multiple levels of SLN are not indicated because a clinical benefit was not significant [48,49].

The ACOSOG Z0011 trial 2 is a landmark article that changed paradigm shifts in 2011. ACOSOG Z0011 is a randomized trial, non-inferiority study which suggested that completion ALND is not necessary in T1 and T2 breast cancer patients who received whole-breast radiation since disease-free survival and recurrence rates did not appear to differ between the patients who had completion ALND versus those who had SLN biopsy alone and had up to two positive SLNs. All patients in this study received adjuvant radiation therapy. The study consisted of 813 positive SLN patients randomized to 388 patients who had ALND and 425 patients without ALND. Criticisms of ACOSOG Z0011 study have been that the case selection was biased toward older women, predominantly estrogen receptor (ER) positive tumors (younger women with ER negative tumors were underrepresented), lost to follow-up was significant (21% in the complete ALND and 17% in the SLN alone groups) and short clinical follow-up of 6.3 years.

The IBCSG 23-01 was a multicenter randomized phase 3 trial in breast cancer size of less or equal to 5 cm, separating pN0(i+) and pN1mi without extracapsular invasion of SLN based on H&E slide to 464 patients who had ALND and 467 patients who did not have ALND with a median follow-up of 5 years. The result was similar to the ACOSOG Z0011 trial stating that ALND was not necessary since there is no adverse effect on survival [50].

Additionally, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 10981-22023, the After Mapping of the Axilla: Radiotherapy or Surgery (AMAROS) which is a randomized, multicentric, phase 3 non-inferiority trial also supported ACOSOG Z0011 findings that there are no differences when complete ALND verses axillary radiation therapy from positive SLN patients in early breast cancer when the usage of chemotherapy, or hormone therapy was factored in. Traditionally ALND has been a guide to adjuvant chemotherapy and based on this study, the information provided by complete ALND is no longer useful [51,52].

Another prospective clinical trial study, the POSNOC (Positive Sentinel Node: Adjuvant Therapy Alone versus Adjuvant Therapy Plus Clearance or Axillary Radiotherapy) trial is still open and recruiting patients till 3/31/18 in the United Kingdom which is a pragmatic, randomized, multicentric and non-inferiority trial for early breast cancer with one or two SLN macrometastases.

CONCLUSION AND COMMENTARY

The growing body of literature from both retrospective and prospective studies advocates conservatism. Completion ALND is not providing benefit of OS and disease-free survival in microscopic metastatic SLN [pN0(i+) and pN1mi]. Even macrometastasis in one or two SLN(s) in ACOSOG Z0011 did not affect OS. There is mounting evidence to support that SLN biopsy alone can be a standard practice demonstrating its efficacy, accuracy in staging and equivalent survival outcome when compared to complete ALND and SLNB alone in T1–T2 breast cancer [45,53-57].

Recently, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) looked into 2,074 patients who had wither ITC or micrometastasis in SLN and found no significant difference in OS and axillary recurrence rate between patients who had completion ALND or no ALND. The study add growing literature that it is safe to omit ALND in minimal metastatic disease in the SLN [58].

From a pathologists’ point of view, we need to ask the following questions: Are we reporting small volume metastasis in vain? Is separating pN0(i+) or pN1mi really necessary? While most of the cases N-staging are straightforward, we do still face ambiguous cases. When we perform tedious work by counting metastatic tumor cells, we want to make sure this work has value in clinical contribution. The evidence shows that separating small volume N-stage or even macrometastasis is not affecting clinical management to perform completion ALND or OS in early stage breast cancers. Also all other organ systems in the same AJCC Staging Manual for colon cancer, gynecologic cancer, even melanoma which the technique of SLN was first described do not practice as in breast N-staging; there is no pN0 (i+) or pN1mi. Metastatic carcinoma when seen by either H&E or IHC stain slide is called metastatic carcinoma. IHC stain is used discretionally by pathologists to confirm the presence of metastasis as needed if there is suspicious area by H&E slide. Why should breast cancer N-stage be any different from other organs?

As we understand that ALND dissection is no longer needed or necessary in many early breast cancers, the necessity of performing multiple levels, IHC stain, frozen section and molecular studies on SLN needs to be revisited.

Recently the AJCC Executive Committee announced a mid-2016 publication date for the 8th edition AJCC Cancer Staging System during its September 2013 Annual Meeting held in Chicago. The 8th edition will be effective for all cancer cases recorded on or after January 1, 2017. Key activities prior to the 2016 publication data are 1. Analysis of data collected since the 7th edition’s release in 2010, 2. Validation of prognostic and predictive factors for incorporation in the staging system and 3. Collaboration with the cancer care and surveillance community to set the standard to anticipate, communicate, and help incorporate staging system changes. Breast Expert Panel leaders are Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, MD, Breast Medical Oncologist and Armando Giuliano, MD, Breast Surgical Oncologist.

As a pathologist, I hope to see the 8th edition AJCC Cancer Staging System for N-stage to be clinically relevant with simple and practical application without further arbitrary cutoffs to reduce subjective interpretation and to enhance agreement between both academic and community based pathologists all over the world.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trojani M, de Mascarel I, Bonichon F, Coindre JM, Delsol G. Micrometastases to axillary lymph nodes from carcinoma of breast: detection by immunohistochemistry and prognostic significance. Br J Cancer. 1987;55:303–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hainsworth PJ, Tjandra JJ, Stillwell RG, et al. Detection and significance of occult metastases in node-negative breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1993;80:459–63. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clare SE, Sener SF, Wilkens W, Goldschmidt R, Merkel D, Winchester DJ. Prognostic significance of occult lymph node metastases in node-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:447–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02303667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedmak DD, Meineke TA, Knechtges DS, Anderson J. Prognostic significance of cytokeratin-positive breast cancer metastases. Mod Pathol. 1989;2:516–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen ZL, Wen DR, Coulson WF, Giuliano AE, Cochran AJ. Occult metastases in the axillary lymph nodes of patients with breast cancer node negative by clinical and histologic examination and conventional histology. Dis Markers. 1991;9:239–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Mascarel I, Bonichon F, Coindre JM, Trojani M. Prognostic significance of breast cancer axillary lymph node micrometastases assessed by two special techniques: reevaluation with longer follow-up. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:523–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denoix PF. Tumor, node and metastasis (TNM) Bull Inst Nat Hyg (Paris) 1944;1:1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Hensen DE, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singletary SE, Allred C, Ashley P, et al. Staging system for breast cancer: revisions for the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:803–19. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huvos AG, Hutter RV, Berg JW. Significance of axillary macrometastases and micrometastases in mammary cancer. Ann Surg. 1971;173:44–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197101000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher ER, Palekar A, Rockette H, Redmond C, Fisher B. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (Protocol No. 4). V. Significance of axillary nodal micro- and macrometastases. Cancer. 1978;42:2032–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197810)42:4<2032::aid-cncr2820420453>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasser IA, Lee AK, Bosari S, Saganich R, Heatley G, Silverman ML. Occult axillary lymph node metastases in “node-negative” breast carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:950–7. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90108-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleiweiss IJ, Nagi CS, Jaffer S. Axillary sentinel lymph nodes can be falsely positive due to iatrogenic displacement and transport of benign epithelial cells in patients with breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2013–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgibbons PL, Page DL, Weaver D, et al. Prognostic factors in breast cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:966–78. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0966-PFIBC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen NM, Grube BJ, Giuliano AE. The time has come to change the algorithm for the surgical management of early breast cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1131–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.10.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singletary SE, Connolly JL. Breast cancer staging: working with the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:37–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106:4–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCready DR, Yong WS, Ng AK, Miller N, Done S, Youngson B. Influence of the new AJCC breast cancer staging system on sentinel lymph node positivity and false-negative rates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:873–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cserni G, Gregori D, Merletti F, et al. Meta-analysis of non-sentinel node metastases associated with micrometastatic sentinel nodes in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1245–52. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viale G, Maiorano E, Mazzarol G, et al. Histologic detection and clinical implications of micrometastases in axillary sentinel lymph nodes for patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:1378–84. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6<1378::aid-cncr1460>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Deurzen CH, de Boer M, Monninkhof EM, et al. Non-sentinel lymph node metastases associated with isolated breast cancer cells in the sentinel node. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1574–80. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly JL. Changes and problematic areas in interpretation of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th Edition, for breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:287–91. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-287-CAPAII. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cserni G, Bianchi S, Vezzosi V, et al. Variations in sentinel node isolated tumour cells/micrometastasis and non-sentinel node involvement rates according to different interpretations of the TNM definitions. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cserni G, Bianchi S, Boecker W, et al. Improving the reproducibility of diagnosing micrometastases and isolated tumor cells. Cancer. 2005;103:358–67. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cserni G, Sapino A, Decker T. Discriminating between micrometastases and isolated tumor cells in a regional and institutional setting. Breast. 2006;15:347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner RR, Weaver DL, Cserni G, et al. Nodal stage classification for breast carcinoma: improving interobserver reproducibility through standardized histologic criteria and image-based training. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:258–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Mascarel I, MacGrogan G, Debled M, Brouste V, Mauriac L. Distinction between isolated tumor cells and micrometastases in breast cancer: is it reliable and useful? Cancer. 2008;112:1672–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cserni G, Amendoeira I, Bianchi S, et al. Distinction of isolated tumour cells and micrometastasis in lymph nodes of breast cancer patients according to the new Tumour Node Metastasis (TNM) definitions. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:887–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vestjens JH, Pepels MJ, de Boer M, et al. Relevant impact of central pathology review on nodal classification in individual breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2561–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apple SK, Moatamed NA, Finck RH, Sullivan PS. Accurate classification of sentinel lymph node metastases in patients with lobular breast carcinoma. Breast. 2010;19:360–4. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7703–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen SL, Hoehne FM, Giuliano AE. The prognostic significance of micrometastases in breast cancer: a SEER population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3378–84. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Boer M, van Deurzen CH, van Dijck JA, et al. Micrometastases or isolated tumor cells and the outcome of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:653–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugliese MS, Beatty JD, Tickman RJ, et al. Impact and outcomes of routine microstaging of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer: significance of the pN0(i+) and pN1mi categories. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:113–20. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen NM, Grube B, Ye X, et al. Impact of micrometastases in the sentinel node of patients with invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4679–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Hansen NM, et al. Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone and completion axillary lymph node dissection for node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2946–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi M, Giordano SH, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. Trends in and outcomes from sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone vs. SLNB with axillary lymph node dissection for node-positive breast cancer patients: experience from the SEER database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17 Suppl 3:343–51. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1253-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cyr A, Gao F, Gillanders WE, Aft RL, Eberlein TJ, Margenthaler JA. Disease recurrence in sentinel node-positive breast cancer patients forgoing axillary lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3185–91. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2547-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vergara-Lluri ME, Prati R, Petersen J, Omidvar Y, Apple SK. Recurrence rates in breast cancer patients who had sentinel lymph node biopsy alone versus completion axillary lymph node dissection: a 7-year clinical follow-up study. Breast J. 2014;20:666–8. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu Y, Chung D, Cao MA, Apple S, Chang H. Is axillary lymph node dissection necessary after sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with mastectomy and pathological N1 breast cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:4109–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:927–33. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver DL, Ashikaga T, Krag DN, et al. Effect of occult metastases on survival in node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:412–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weaver DL, Le UP, Dupuis SL, et al. Metastasis detection in sentinel lymph nodes: comparison of a limited widely spaced (NSABP protocol B-32) and a comprehensive narrowly spaced paraffin block sectioning strategy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1583–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b274e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hieken TJ, Boughey JC. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases: commentary on the IBCSG 23-01 Trial. Gland Surg. 2013;2:128–32. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2013.07.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Straver ME, Meijnen P, van Tienhoven G, et al. Role of axillary clearance after a tumor-positive sentinel node in the administration of adjuvant therapy in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:731–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.AMAROS The EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial [Internet] AMAROS, 2010 [cited 2015 Oct 1]. Available from: http://research.nki.nl/amaros/

- 53.Mansel RE, Fallowfield L, Kissin M, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy versus standard axillary treatment in operable breast cancer: the ALMANAC Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:599–609. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gill G, SNAC Trial Group of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) and NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre Sentinel-lymphnode-based management or routine axillary clearance? One-year outcomes of sentinel node biopsy versus axillary clearance (SNAC): a randomized controlled surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:266–75. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3657–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cote RJ, Peterson HF, Chaiwun B, et al. Role of immunohistochemical detection of lymph-node metastases in management of breast cancer. International Breast Cancer Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:896–900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guenther JM, Hansen NM, DiFronzo LA, et al. Axillary dissection is not required for all patients with breast cancer and positive sentinel nodes. Arch Surg. 2003;138:52–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tvedskov TF, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Christiansen P, Balslev E, Kroman N. Prognostic significance of axillary dissection in breast cancer patients with micrometastases or isolated tumor cells in sentinel nodes: a nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;153:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]