Abstract

Although proteins mediate highly ordered DNA organization in vivo, theoretical studies suggest that homologous DNA duplexes can preferentially associate with one another even in the absence of proteins. Here we combine molecular dynamics simulations with single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments to examine the interactions between duplex DNA in the presence of spermine, a biological polycation. We find that AT-rich DNA duplexes associate more strongly than GC-rich duplexes, regardless of the sequence homology. Methyl groups of thymine acts as a steric block, relocating spermine from major grooves to interhelical regions, thereby increasing DNA–DNA attraction. Indeed, methylation of cytosines makes attraction between GC-rich DNA as strong as that between AT-rich DNA. Recent genome-wide chromosome organization studies showed that remote contact frequencies are higher for AT-rich and methylated DNA, suggesting that direct DNA–DNA interactions that we report here may play a role in the chromosome organization and gene regulation.

Theoretical studies suggest that homologous DNA duplexes can preferentially associate with one another in the absence of proteins. Here, the authors show that GC-rich DNA with methylated cytosine and AT-rich DNA duplexes associate more strongly than GC-rich duplexes regardless of the sequence homology.

Theoretical studies suggest that homologous DNA duplexes can preferentially associate with one another in the absence of proteins. Here, the authors show that GC-rich DNA with methylated cytosine and AT-rich DNA duplexes associate more strongly than GC-rich duplexes regardless of the sequence homology.

Formation of a DNA double helix occurs through Watson–Crick pairing mediated by the complementary hydrogen bond patterns of the two DNA strands and base stacking. Interactions between double-stranded (ds)DNA molecules in typical experimental conditions containing mono- and divalent cations are repulsive1, but can turn attractive in the presence of high-valence cations2. Theoretical studies have identified the ion–ion correlation effect as a possible microscopic mechanism of the DNA condensation phenomena3,4,5. Theoretical investigations have also suggested that sequence-specific attractive forces might exist between two homologous fragments of dsDNA6, and this ‘homology recognition' hypothesis was supported by in vitro atomic force microscopy7 and in vivo point mutation assays8. However, the systems used in these measurements were too complex to rule out other possible causes such as Watson–Crick strand exchange between partially melted DNA or protein-mediated association of DNA.

Here we present direct evidence for sequence-dependent attractive interactions between dsDNA molecules that neither involve intermolecular strand exchange nor are mediated by proteins. Further, we find that the sequence-dependent attraction is controlled not by homology—contradictory to the ‘homology recognition' hypothesis6—but by a methylation pattern. Unlike the previous in vitro study that used monovalent (Na+) or divalent (Mg2+) cations7, we presumed that for the sequence-dependent attractive interactions to operate polyamines would have to be present. Polyamine is a biological polycation present at a millimolar concentration in most eukaryotic cells and essential for cell growth and proliferation9,10. Polyamines are also known to condense DNA in a concentration-dependent manner2,11. In this study, we use spermine4+ (Sm4+) that contains four positively charged amine groups per molecule.

Results

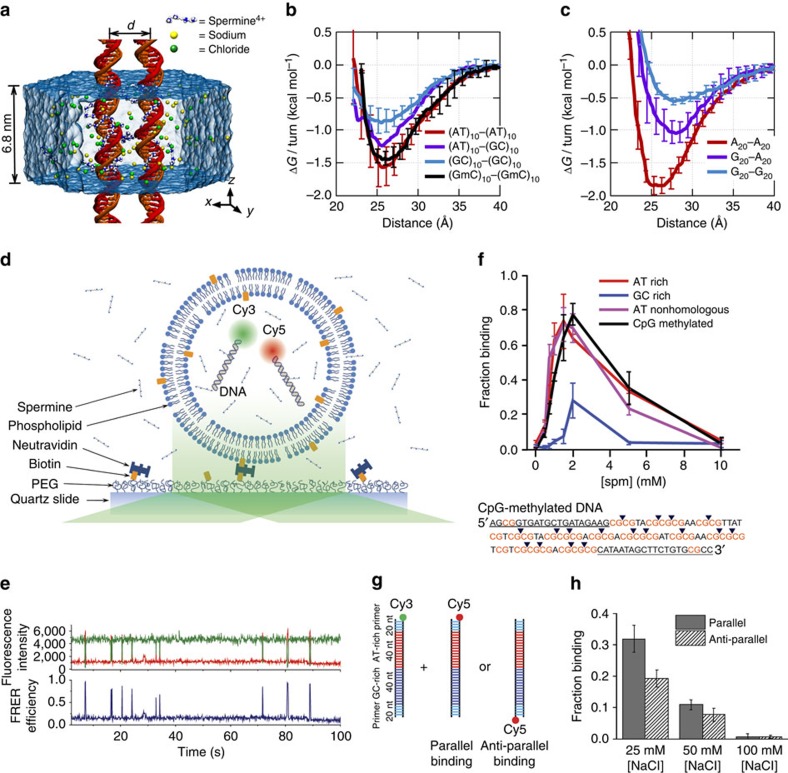

Sequence dependence of DNA–DNA forces

To characterize the molecular mechanisms of DNA–DNA attraction mediated by polyamines, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations where two effectively infinite parallel dsDNA molecules, 20 base pairs (bp) each in a periodic unit cell, were restrained to maintain a prescribed inter-DNA distance; the DNA molecules were free to rotate about their axes. The two DNA molecules were submerged in 100 mM aqueous solution of NaCl that also contained 20 Sm4+ molecules; thus, the total charge of Sm4+, 80 e, was equal in magnitude to the total charge of DNA (2 × 2 × 20 e, two unit charges per base pair; Fig. 1a). Repeating such simulations at various inter-DNA distances and applying weighted histogram analysis12 yielded the change in the interaction free energy (ΔG) as a function of the DNA–DNA distance (Fig. 1b,c). In a broad agreement with previous experimental findings13, ΔG had a minimum, ΔGmin, at the inter-DNA distance of 25−30 Å for all sequences examined, indeed showing that two duplex DNA molecules can attract each other. The free energy of inter-duplex attraction was at least an order of magnitude smaller than the Watson–Crick interaction free energy of the same length DNA duplex. A minimum of ΔG was not observed in the absence of polyamines, for example, when divalent or monovalent ions were used instead14,15.

Figure 1. Polyamine-mediated DNA sequence recognition observed in MD simulations and smFRET experiments.

(a) Set-up of MD simulations. A pair of parallel 20-bp dsDNA duplexes is surrounded by aqueous solution (semi-transparent surface) containing 20 Sm4+ molecules (which compensates exactly the charge of DNA) and 100 mM NaCl. Under periodic boundary conditions, the DNA molecules are effectively infinite. A harmonic potential (not shown) is applied to maintain the prescribed distance between the dsDNA molecules. (b,c) Interaction free energy of the two DNA helices as a function of the DNA–DNA distance for repeat-sequence DNA fragments (b) and DNA homopolymers (c). (d) Schematic of experimental design. A pair of 120-bp dsDNA labelled with a Cy3/Cy5 FRET pair was encapsulated in a ∼200-nm diameter lipid vesicle; the vesicles were immobilized on a quartz slide through biotin–neutravidin binding. Sm4+ molecules added after immobilization penetrated into the porous vesicles. The fluorescence signals were measured using a total internal reflection microscope. (e) Typical fluorescence signals indicative of DNA–DNA binding. Brief jumps in the FRET signal indicate binding events. (f) The fraction of traces exhibiting binding events at different Sm4+ concentrations for AT-rich, GC-rich, AT nonhomologous and CpG-methylated DNA pairs. The sequence of the CpG-methylated DNA specifies the methylation sites (CG sequence, orange), restriction sites (BstUI, triangle) and primer region (underlined). The degree of attractive interaction for the AT nonhomologous and CpG-methylated DNA pairs was similar to that of the AT-rich pair. All measurements were done at [NaCl]=50 mM and T=25 °C. (g) Design of the hybrid DNA constructs: 40-bp AT-rich and 40-bp GC-rich regions were flanked by 20-bp common primers. The two labelling configurations permit distinguishing parallel from anti-parallel orientation of the DNA. (h) The fraction of traces exhibiting binding events as a function of NaCl concentration at fixed concentration of Sm4+ (1 mM). The fraction is significantly higher for parallel orientation of the DNA fragments.

Unexpectedly, we found that DNA sequence has a profound impact on the strength of attractive interaction. The absolute value of ΔG at minimum relative to the value at maximum separation, |ΔGmin|, showed a clearly rank-ordered dependence on the DNA sequence: |ΔGmin| of (A)20>|ΔGmin| of (AT)10>|ΔGmin| of (GC)10>|ΔGmin| of (G)20. Two trends can be noted. First, AT-rich sequences attract each other more strongly than GC-rich sequences16. For example, |ΔGmin| of (AT)10 (1.5 kcal mol−1 per turn) is about twice |ΔGmin| of (GC)10 (0.8 kcal mol−1 per turn) (Fig. 1b). Second, duplexes having identical AT content but different partitioning of the nucleotides between the strands (that is, (A)20 versus (AT)10 or (G)20 versus (GC)10) exhibit statistically significant differences (∼0.3 kcal mol−1 per turn) in the value of |ΔGmin|.

To validate the findings of MD simulations, we performed single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET)17 experiments of vesicle-encapsulated DNA molecules. Equimolar mixture of donor- and acceptor-labelled 120-bp dsDNA molecules was encapsulated in sub-micron size, porous lipid vesicles18 so that we could observe and quantitate rare binding events between a pair of dsDNA molecules without triggering large-scale DNA condensation2. Our DNA constructs were long enough to ensure dsDNA–dsDNA binding that is stable on the timescale of an smFRET measurement, but shorter than the DNA's persistence length (∼150 bp (ref. 19)) to avoid intramolecular condensation20. The vesicles were immobilized on a polymer-passivated surface, and fluorescence signals from individual vesicles containing one donor and one acceptor were selectively analysed (Fig. 1d). Binding of two dsDNA molecules brings their fluorescent labels in close proximity, increasing the FRET efficiency (Fig. 1e).

FRET signals from individual vesicles were diverse. Sporadic binding events were observed in some vesicles, while others exhibited stable binding; traces indicative of frequent conformational transitions were also observed (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Such diverse behaviours could be expected from non-specific interactions of two large biomolecules having structural degrees of freedom. No binding events were observed in the absence of Sm4+ (Supplementary Fig. 1B) or when no DNA molecules were present. To quantitatively assess the propensity of forming a bound state, we chose to use the fraction of single-molecule traces that showed any binding events within the observation time of 2 min (Methods). This binding fraction for the pair of AT-rich dsDNAs (AT1, 100% AT in the middle 80-bp section of the 120-bp construct) reached a maximum at ∼2 mM Sm4+ (Fig. 1f), which is consistent with the results of previous experimental studies2,3. In accordance with the prediction of our MD simulations, GC-rich dsDNAs (GC1, 75% GC in the middle 80 bp) showed much lower binding fraction at all Sm4+ concentrations (Fig. 1b,c). Regardless of the DNA sequence, the binding fraction reduced back to zero at high Sm4+ concentrations, likely due to the resolubilization of now positively charged DNA–Sm4+ complexes2,3,13.

Because the donor and acceptor fluorophores were attached to the same sequence of DNA, it remained possible that the sequence homology between the donor-labelled DNA and the acceptor-labelled DNA was necessary for their interaction6. To test this possibility, we designed another AT-rich DNA construct AT2 by scrambling the central 80-bp section of AT1 to remove the sequence homology (Supplementary Table 1). The fraction of binding traces for this nonhomologous pair of donor-labelled AT1 and acceptor-labelled AT2 was comparable to that for the homologous AT-rich pair (donor-labelled AT1 and acceptor-labelled AT1) at all Sm4+ concentrations tested (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, this data set rules out the possibility that the higher binding fraction observed experimentally for the AT-rich constructs was caused by inter-duplex Watson–Crick base pairing of the partially melted constructs.

Next, we designed a DNA construct named ATGC, containing, in its middle section, a 40-bp AT-rich segment followed by a 40-bp GC-rich segment (Fig. 1g). By attaching the acceptor to the end of either the AT-rich or GC-rich segments, we could compare the likelihood of observing the parallel binding mode that brings the two AT-rich segments together and the anti-parallel binding mode. Measurements at 1 mM Sm4+ and 25 or 50 mM NaCl indicated a preference for the parallel binding mode by ∼30% (Fig. 1h). Therefore, AT content can modulate DNA–DNA interactions even in a complex sequence context. Note that increasing the concentration of NaCl while keeping the concentration of Sm4+ constant enhances competition between Na+ and Sm4+ counterions, which reduces the concentration of Sm4+ near DNA and hence the frequency of dsDNA–dsDNA binding events (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Methylation determines the strength of DNA–DNA attraction

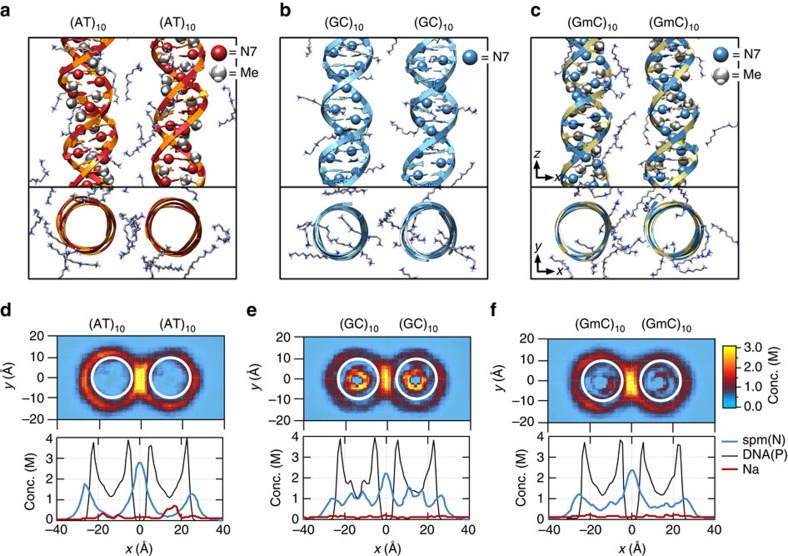

Analysis of the MD simulations revealed the molecular mechanism of the polyamine-mediated sequence-dependent attraction (Fig. 2). In the case of the AT-rich fragments, the bulky methyl group of thymine base blocks Sm4+ binding to the N7 nitrogen atom of adenine, which is the cation-binding hotspot21,22. As a result, Sm4+ is not found in the major grooves of the AT-rich duplexes and resides mostly near the DNA backbone (Fig. 2a,d). Such relocated Sm4+ molecules bridge the two DNA duplexes better, accounting for the stronger attraction16,23,24,25. In contrast, significant amount of Sm4+ is adsorbed to the major groove of the GC-rich helices that lacks cation-blocking methyl group (Fig. 2b,e).

Figure 2. Molecular mechanism of polyamine-mediated DNA sequence recognition.

(a–c) Representative configurations of Sm4+ molecules at the DNA–DNA distance of 28 Å for the (AT)10–(AT)10 (a), (GC)10–(GC)10 (b) and (GmC)10–(GmC)10 (c) DNA pairs. The backbone and bases of DNA are shown as ribbon and molecular bond, respectively; Sm4+ molecules are shown as molecular bonds. Spheres indicate the location of the N7 atoms and the methyl groups. (d–f) The average distributions of cations for the three sequence pairs featured in a–c. Top: density of Sm4+ nitrogen atoms (d=28 Å) averaged over the corresponding MD trajectory and the z axis. White circles (20 Å in diameter) indicate the location of the DNA helices. Bottom: the average density of Sm4+ nitrogen (blue), DNA phosphate (black) and sodium (red) atoms projected onto the DNA–DNA distance axis (x axis). The plot was obtained by averaging the corresponding heat map data over y=[−10, 10] Å. See Supplementary Figs 4 and 5 for the cation distributions at d=30, 32, 34 and 36 Å.

If indeed the extra methyl group in thymine, which is not found in cytosine, is responsible for stronger DNA–DNA interactions, we can predict that cytosine methylation, which occurs naturally in many eukaryotic organisms and is an essential epigenetic regulation mechanism26, would also increase the strength of DNA–DNA attraction. MD simulations showed that the GC-rich helices containing methylated cytosines (mC) lose the adsorbed Sm4+ (Fig. 2c,f) and that |ΔGmin| of (GC)10 increases on methylation of cytosines to become similar to |ΔGmin| of (AT)10 (Fig. 1b).

To experimentally assess the effect of cytosine methylation, we designed another GC-rich construct GC2 that had the same GC content as GC1 but a higher density of CpG sites (Supplementary Table 1). The CpG sites were then fully methylated using M. SssI methyltransferase (Supplementary Fig. 3; Methods). As predicted from the MD simulations, methylation of the GC-rich constructs increased the binding fraction to the level of the AT-rich constructs (Fig. 1f).

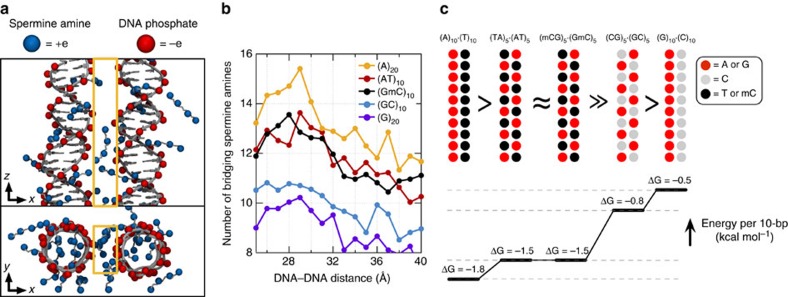

The sequence dependence of |ΔGmin| and its relation to the Sm4+ adsorption patterns can be rationalized by examining the number of Sm4+ molecules shared by the dsDNA molecules (Fig. 3a). An Sm4+ cation adsorbed to the major groove of one dsDNA is separated from the other dsDNA by at least 10 Å, contributing much less to the effective DNA–DNA attractive force than a cation positioned between the helices, that is, the ‘bridging' Sm4+ (ref. 23). An adsorbed Sm4+ also repels other Sm4+ molecules due to like-charge repulsion, lowering the concentration of bridging Sm4+. To demonstrate that the concentration of bridging Sm4+ controls the strength of DNA–DNA attraction, we computed the number of bridging Sm4+ molecules, Nspm (Fig. 3b). Indeed, the number of bridging Sm4+ molecules ranks in the same order as |ΔGmin|: Nspm of (A)20>Nspm of (AT)10≈Nspm of (GmC)10>Nspm of (GC)10>Nspm of (G)20. Thus, the number density of nucleotides carrying a methyl group (T and mC) is the primary determinant of the strength of attractive interaction between two dsDNA molecules. At the same time, the spatial arrangement of the methyl group carrying nucleotides can affect the interaction strength as well (Fig. 3c). The number of methyl groups and their distribution in the (AT)10 and (GmC)10 duplex DNA are identical, and so are their interaction free energies, |ΔGmin| of (AT)10≈|ΔGmin| of (GmC)10. For AT-rich DNA sequences, clustering of the methyl groups repels Sm4+ from the major groove more efficiently than when the same number of methyl groups is distributed along the DNA (Fig. 3b). Hence, |ΔGmin| of (A)20>|ΔGmin| of (AT)10. For GC-rich DNA sequences, clustering of the cation-binding sites (N7 nitrogen) attracts more Sm4+ than when such sites are distributed along the DNA (Fig. 3b), hence |ΔGmin| is larger for (GC)10 than for (G)20.

Figure 3. Methylation modulates the interaction free energy of two dsDNA molecules by altering the number of bridging Sm4+.

(a) Typical spatial arrangement of Sm4+ molecules around a pair of DNA helices. The phosphates groups of DNA and the amine groups of Sm4+ are shown as red and blue spheres, respectively. ‘Bridging' Sm4+ molecules reside between the DNA helices. Orange rectangles illustrate the volume used for counting the number of bridging Sm4+ molecules. (b) The number of bridging amine groups as a function of the inter-DNA distance. The total number of Sm4+ nitrogen atoms was computed by averaging over the corresponding MD trajectory and the 10 Å (x axis) by 20 Å (y axis) rectangle prism volume (a) centred between the DNA molecules. (c) Schematic representation of the dependence of the interaction free energy of two DNA molecules on their nucleotide sequence. The number and spatial arrangement of nucleotides carrying a methyl group (T or mC) determine the interaction free energy of two dsDNA molecules.

Discussion

Genome-wide investigations of chromosome conformations using the Hi–C technique revealed that AT-rich loci form tight clusters in human nucleus27,28. Gene or chromosome inactivation is often accompanied by increased methylation of DNA29 and compaction of facultative heterochromatin regions30. The consistency between those phenomena and our findings suggest the possibility that the polyamine-mediated sequence-dependent DNA–DNA interaction might play a role in chromosome folding and epigenetic regulation of gene expression.

Methods

MD protocols

All MD simulations were carried out in a constant-temperature/constant-pressure ensemble using the Gromacs 4.5.5 package31. Integration time step was 2 fs. The temperature was set to 300 K using the Nosé–Hoover scheme32,33. The pressure in the xy plane (normal to DNA) was kept constant at 1 bar using the Parrinello–Rahman scheme34; the length of the box in the z direction was kept constant at 68 Å. Van der Waals forces were evaluated using a 7–10-Å switching scheme. Long-range electrostatic forces were computed using the particle-Mesh Ewald summation scheme35, a 1.5-Å Fourier-space grid and a 12-Å cutoff for the real-space Coulomb interaction. Covalent bonds to hydrogen in water, and in non-water molecules were constrained using SETTLE36 and LINCS37 algorithms, respectively. All simulations were carried out using the AMBER99bsc0 force field for DNA38,39, NaCl parameters of Joung et al.40 and the TIP3P water model41. Parameters describing spermine (NH2(CH2)3NH(CH2)4NH(CH2)3NH2) were based on the AMBER99 force field24. Custom Van der Waals parameters (CUFIX) were used to describe non-bonded interactions between spermine amine and DNA phosphate, between sodium ion and DNA phosphate, and between sodium and chloride ions14,15,25,42.

Potential of mean force calculations

Initially, a pair of 20-bp duplexes DNA was placed in a hexagonal water box parallel to the z axis. The water box measured ∼130 Å within the xy plane and 68 Å along the z axis. Each DNA strand was effectively infinite under the periodic boundary conditions. The relatively large lateral size of the simulation box was chosen to avoid finite size artefacts. Twenty Sm4+ molecules were randomly placed in the box to neutralize the charge of the DNA molecules; sodium and chloride ions were added corresponding to a 100 mM concentration. Five variants of the system were built, different only by the nucleotide sequence of the DNA molecules. Each system was equilibrated for at least 50 ns; the DNA molecules were free to move about the simulation system during the equilibration. The last frame of each equilibration trajectory was used to initiate umbrella sampling simulations that determined the free energy (ΔG) of the pair of parallel dsDNA molecules as a function of the inter-DNA distance. The reaction coordinate was defined as the distance between the centres of mass of the two DNA molecules projected onto the xy plane. The harmonic restraints used for umbrella sampling simulations had a force constant of 2,000 kJ mol−1 nm−2; the inter-DNA distance varied from 23 to 42 Å with a 1-Å window spacing. The umbrella sampling simulations were ∼200 ns in duration in each sampling window; the inter-DNA distance was recorded every 2 ps. Except for the umbrella restraining potential, no additional constraints were applied to DNA. The weighted histogram analysis method implemented in the Gromacs package was used for the reconstruction of the free energy from the recorded inter-DNA distance data12.

DNA design and synthesis

Supplementary Table 1 specifies the design of the 120-bp long DNA template and other molecules used in this study. All DNA constructs had the same 20-bp primer regions at both the ends of the constructs (primer A and B, designed by Clone Manager Suite 7). Primer B was labelled at the 5′ end with either Cy3 or Cy5 dye with the efficiency of 90% or higher. The nucleotide sequence of the middle 80-bp section of the constructs varied among the constructs. Note that we did not use 100% GC constructs because they are known to contain quadruplexes43. The 120-bp DNA templates were made by Integrated DNA Technologies. The dsDNA constructs were synthesized from these templates and two primers by PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix kit (New England BioLabs) and following the standard protocol of the kit. The PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and their concentrations were measured by ultraviolet–visible absorption. The CpG-methylated constructs were obtained by performing an 8-h methylation reaction on the dsDNA constructs using the CpG methyltransferase M. SssI (New England BioLabs, M0226L) following the company's standard protocol. The product was purified by the PCR purification kit. The methylation efficiency was estimated by digesting the dsDNA products with the BstUI restriction enzyme (New England BioLabs, R0518L), which can cut only unmethylated CGCG sequence, and subsequent electrophoresis of the digested fragments through a polyacrylamide gel (Supplementary Fig. 3).

DNA encapsulation

We encapsulated the purified dsDNA in lipid vesicles by modifying the protocol previously developed for single-stranded DNA18. In short, we mixed biotinyl cap phosphoethanolamine with 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine in 1:100 molar ratio, dried and hydrated with buffer solution of 100 mM NaCl, and 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0). After hydration, the mixture was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed seven times to create large unilamellar vesicles. The desired pair of dsDNAs was added to the solution, each at 400 nM concentration (corresponding to 1 molecule in a spherical volume of 200 nm diameter) and then the solution was extruded through a membrane filter with 200 nm pores to create uniformly sized unilamellar vesicles. Typical acceptor co-encapsulation yield (defined as the fraction of vesicles detected with a pair of donor and acceptor among all vesicles with any acceptor signal) was 10–20%.

Single-molecule measurements

The lipid vesicles were immobilized on a PEG-coated surface through the biotin–neutravidin interaction (Fig. 2a). Fluorescence signals from individual vesicles were collected by total internal reflection microscopy as previously described44. Imaging solution contained 1 mg ml−1 glucose oxidase, 0.04 mg ml−1 catalase, 0.8% dextrose, saturated Trolox (∼3 mM) and 25 mM Tris in addition to the desired amounts of NaCl and Sm4+. The gel–liquid transition temperature of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine is 24 °C, which results in a bistable membrane structure at room temperature, allowing the exchange of ions and small molecules (Sm4+, Trolox and so on) through the membrane. All measurements and solution exchanges were carried out at 25 °C. Fluorescence movies were taken with the rate of 100 ms per frame. For Cy3 and Cy5 dyes, 532- and 647-nm solid-state lasers were used as the excitation sources, respectively.

Analysis of single-molecule traces

We quantified the strength of binding by measuring the fraction of traces that showed any binding events among all traces containing a single pair of donor and acceptor dyes. Binding traces exhibited a variety of behaviours (Supplementary Fig. 1A), which in part can be attributed to the variation in the vesicle size. First, we selected the traces containing single pair of Cy3 and Cy5 by examining their bleaching steps and signal intensities from either excitation. Among these, we selected the traces showing clear binding behaviours. The criteria we used as the binding behaviours was either the FRET efficiency jumping over 0.5 or showing no clear jumps but maintaining a FRET level of 0.25 or higher. The number of these binding traces over the number of all single pair traces was measured for triplicate data sets at each Sm4+ concentrations for each DNA sample. The error bars in Fig. 1f represents the s.e. of mean between these triplicate measurements.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yoo, J. et al. Direct evidence for sequence-dependent attraction between double-stranded DNA controlled by methylation. Nat. Commun. 7:11045 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11045 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-5 and Supplementary Table 1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (USA) through the PHY-1430124 award. J.Y. and A.A. gladly acknowledge supercomputer time provided through XSEDE Allocation Grant MCA05S028 and the Blue Waters Sustained Petascale Computer System (UIUC). H.K. was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grants 2014R1A1A1003949, IBS-R020-D1 and the 2014 Research Fund (1.130091.01) of UNIST. T.H. was funded in part by a grant from National Institutes of Health (GM065367), and is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. We thank Dr Sang Hak Lee for the discussion of the DNA methylation protocol.

Footnotes

Author contributions J.Y., H.K., A.A. and T.H. designed all computational and experimental assays. J.Y. and H.K. performed the simulations and experiments, respectively. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, development of the theory and writing of the manuscript.

References

- Rau D. C., Lee B. & Parsegian V. A. Measurement of the repulsive force between polyelectrolyte molecules in ionic solution: hydration forces between parallel DNA double helices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 81, 2621–2625 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspaud E., Olvera de la Cruz M., Sikorav J. L. & Livolant F. Precipitation of DNA by polyamines: a polyelectrolyte behavior. Biophys. J. 74, 381–393 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besteman K., Van Eijk K. & Lemay S. G. Charge inversion accompanies DNA condensation by multivalent ions. Nat. Phys. 3, 641–644 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert J., Doniach S., Das R. & Herschlag D. Understanding nucleic acid-ion interactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 813–841 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosberg A. Y., Nguyen T. T. & Shklovskii B. I. The physics of charge inversion in chemical and biological systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 329–345 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Kornyshev A. A. & Leikin S. Sequence recognition in the pairing of DNA duplexes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3666–3669 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilowicz C. et al. Single molecule detection of direct, homologous, DNA/DNA pairing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19824–19829 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev E. & Kleckner N. Direct recognition of homology between double helices of DNA in Neurospora crassa. Nat. Commun. 5, 3509 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor C. W. & Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 749–790 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. & Thomas T. J. Polyamines in cell growth and cell death: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 244–258 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRouchey J. E. & Rau D. C. Role of amino acid insertions on intermolecular forces between arginine peptide condensed DNA helices: implications for protamine-DNA packaging in sperm. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41985–41992 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Rosenberg J. M., Bouzida D., Swendsen R. H. & Kollman P. A. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 1011–1021 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Todd B. A., Parsegian V. A., Shirahata A., Thomas T. J. & Rau D. C. Attractive forces between cation condensed DNA double helices. Biophys. J. 94, 4775–4782 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. & Aksimentiev A. Improved parametrization of Li+, Na+, K+, and Mg2+ ions for all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of nucleic acid systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 45–50 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. & Aksimentiev A. Improved parameterization of amine-carboxylate and amine-phosphate interactions for molecular dynamics simulations using the CHARMM and AMBER force fields. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 430–443 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolokh I. S. et al. Why double-stranded RNA resists condensation. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 10823–10831 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T. et al. Probing the interaction between two single molecules: fluorescence resonance energy transfer between a single donor and a single acceptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6264–6268 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse I. I., Kim H. & Ha T. A rule of seven in Watson-Crick base-pairing of mismatched sequences. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 623–627 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann C. G., Smith S. B., Bloomfield V. A. & Bustamante C. Ionic effects on the elasticity of single DNA molecules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6185–6190 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hud N. V. & Vilfan I. D. Toroidal DNA condensates: unraveling the fine structure and the role of nucleation in determining size. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34, 295–318 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Chica J., Medina M. A., Sánchez-Jiménez F. & Ramírez F. J. Fourier transform Raman study of the structural specificities on the interaction between DNA and biogenic polyamines. Biophys. J. 80, 443–454 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouameur A. A. & Tajmir-Riahi H. A. Structural analysis of DNA interactions with biogenic polyamines and cobalt(III)hexamine studied by Fourier transform infrared and capillary electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42041–42054 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz M. O. et al. Precipitation of highly charged polyelectrolyte solutions in the presence of multivalent salts. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 5781–5791 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Dai L., Mu Y., Nordenskiöld L. & van der Maarel J. R. Molecular dynamics simulation of multivalent-ion mediated attraction between DNA molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 118301 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. & Aksimentiev A. The structure and intermolecular forces of DNA condensates. Nucleic Acids Res doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R. & Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 33, 245–254 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakaev M. et al. Iterative correction of Hi-C data reveals hallmarks of chromosome organization. Nat. Methods 9, 999–1003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T. & Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 292–301 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rego A., Sinclair P. B., Tao W., Kireev I. & Belmont A. S. The facultative heterochromatin of the inactive X chromosome has a distinctive condensed ultrastructure. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1119–1127 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D. et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose S. & Klein M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 50, 1055–1076 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1695 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M. & Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D. & Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S. & Kollman P. A. SETTLE: An analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithms for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 952–962 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Hess B., Bekker H., Berendesen H. J. C. & Fraaije J. G. E. M. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Cornell W. D. et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Pérez A. et al. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of alpha/gamma conformers. Biophys. J. 92, 3817–3829 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung I. S. & Cheatham T. E. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 9020–9041 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W. & Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. & Aksimentiev A. Competitive binding of cations to duplex DNA revealed through molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 12946–12954 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen D. & Gilbert W. Formation of parallel four-stranded complexes by guanine-rich motifs in DNA and its implications for meiosis. Nature 334, 364–366 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Tang G. Q., Patel S. S. & Ha T. Opening-closing dynamics of the mitochondrial transcription pre-initiation complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 371–380 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-5 and Supplementary Table 1