Summary

Antigen-driven selection has been implicated in the pathogenesis of monoclonal gammopathies. Patients with Gaucher’s disease have an increased risk of monoclonal gammopathies. Here we show that the clonal immunoglobulin in patients with Gaucher’s disease and in mouse models of Gaucher’s disease–associated gammopathy is reactive against lyso-glucosylceramide (LGL1), which is markedly elevated in these patients and mice. Clonal immunoglobulin in 33% of sporadic human monoclonal gammopathies is also specific for the lysolipids LGL1 and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC). Substrate reduction ameliorates Gaucher’s disease–associated gammopathy in mice. Thus, longterm immune activation by lysolipids may underlie both Gaucher’s disease–associated gammopathies and some sporadic monoclonal gammopathies.

Multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) are characterized by clonal expansion of transformed plasma cells.1 Analyses of immunoglobulin genes in tumor cells have provided evidence of antigen-driven selection, with restricted heavy-chain variableregion use and highly hypermutated immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain genes.2–6 However, the antigens underlying the origins of most MGUS and myeloma clones remain unknown. Hyperphosphorylated modification of stomatin (EPB72)-like 2 protein (STOML2, which is identical to paratarg-7) due to the inactivation of protein phosphatase 2A was identified as a target of certain paraproteins and an inherited risk factor for the development of gammopathies.7–9 A recent study identified sumoylated heat-shock protein 90 as another inherited risk factor for plasma-cell dyscrasia.10 However, there remains a need to identify the antigenic origins of MGUS and myeloma that may be amenable to targeted prevention.

Lipids (such as pristane) were implicated in the earliest models of murine plasmacytoma,11 and lipid disorders such as Gaucher’s disease and obesity are associated with an increased risk of myeloma.12,13 The risk of myeloma is markedly higher among patients with Gaucher’s disease, in whom myeloma is now emerging as a leading cause of cancer-related death, than in the general population.13 Glucocerebrosidase deficiency in Gaucher’s disease leads to increases in the level of LGL1.14 Recently, we identified a subset of human and murine LGL1-specific CD1d-restricted type 2 natural killer T cells that constitutively expressed markers of follicular helper T cells and helped in the differentiation of lipid-reactive plasma cells.15 In an earlier study, we found an elevation of type 2 natural killer T cells against another bioactive lysolipid, LPC, in myeloma.16 These studies led us to test whether the clonal immunoglobulin in Gaucher’s disease–associated myeloma and sporadic myeloma was reactive against LGL1 and LPC.

Methods

Patients and Mice

Peripheral-blood or bone marrow samples were obtained from patients with MGUS or myeloma and Gaucher’s disease and from healthy blood donors. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Yale University.

The generation of glucocerebrosidase-deficient (GBA1−/−) mice has been described previously.17 All the mice were bred and maintained in compliance with the guidelines of the institutional animal care committee at Yale University.

Lipids

LGL1 (with purity assessed at >98% by thin-layer chromatography) was purchased from Matreya and was stored frozen (at −20°C) at a concentration of 500 µg per milliliter of 50% dimethyl sulfoxide in distilled water as storage stock.15 LPC was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, dissolved in chloroform at a concentration of 10 mg per milliliter, and stored at −20°C as storage stock.16 Diacylglycerol (DAG; at a concentration of 1 mg per milliliter of chloroform), cardiolipin (at a concentration of 25 mg per milliliter of chloroform), and lipid A (at a concentration of 1 mg per milliliter of dimethyl sulfoxide) were all purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids and were stored at −20°C as storage stock.

Antigen-Specific Immunoblotting

Polyvinylidene fluoride membranes that were saturated with LGL1 and LPC (BioRad) were prepared as described previously.18 Briefly, filters were incubated in 100 µg per milliliter of LGL1 and LPC in 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate, rinsed in phosphatebuffered saline (PBS) and 0.05% Tween 20 detergent, and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Gels for serum protein electrophoresis were blotted onto lipid membranes with the use of modified diffusion blotting.19 After blocking with 1% BSA in PBS and Tween 20 detergent, the membrane was incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibody and was washed and developed with the use of SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Diluted human plasma (1:250 dilution) was added to plates coated with LGL1 (500 ng per well), and the levels of kappa and lambda immunoglobulin light chains were determined with the use of human kappa- and lambda-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantification kits (Bethyl Laboratories).15 To measure hen-egg lysozyme (HEL)–specific and lipid (LGL1, DAG, cardiolipin, and lipid A)–specific antibodies, plates (Nunc- Immuno plate, Thermo Scientific) were coated with an equimolar concentration of antigens overnight at room temperature and then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS and Tween 20 detergent for 2 hours at room temperature. The test serum and purified immunoglobulin sample were diluted in 1% BSA in PBS and Tween 20 detergent and incubated overnight at 4°C. The antigen-specific antibody was detected by HRP-conjugated mouse and human immunoglobulins that had been developed with TMB chromogen (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine; Invitrogen).

Ligand-Mediated Enrichment and Depletion of Clonal Immunoglobulin

Diluted human plasma (1:250 dilution) was incubated with 50 mm3 of either control or sphingosinecoated beads (Echelon Biosciences). Plasma and beads were mixed together by incubating the suspension under rotary agitation (on an orbital shaker) at 4°C. After incubation, the tubes were centrifuged, and the supernatant (flow-through) was analyzed by means of serum protein electrophoresis. The bead pellet was washed four times with the coimmunoprecipitation buffer. The antibody bound to the beads was eluted by boiling the sample in sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer for 5 minutes. Samples were analyzed by means of Western blotting with antihuman IgG, IgA, and IgM heavy chains and kappa and lambda light chains HRP antibodies. Signal intensities were densitometrically quantitated with the use of ImageJ software, version 1.41 (National Institutes of Health).

Injection of GBA1−/− Mice

GBA1−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with either PBS or LGL1 (at a dose of 200 µg per mouse each week for 3 weeks) in a volume of 100 mm3. The mice were euthanized 7 days after the last injection. The diluted serum specimen (1:250 dilution) was used for the quantification of lipid-specific antibodies with the use of ELISA, as described previously.15 HEL, which was purchased from Sigma, was mixed with an adjuvant to yield an emulsion of 2 mg per milliliter, of which 50 mm3 (100 µg per mouse) was injected intraperitoneally in three GBA1−/− mice (8 to 12 weeks old); three GBA1−/− mice received alum (Imject Alum Adjuvant, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS as a control.

Substrate-Reduction Therapy

The drug eliglustat (Genz-112638, Genzyme), a glucocerebroside synthase inhibitor that prevents the overproduction of LGL1, was formulated in a standard rodent food (test diet) in a weight-to-weight ratio of 0.075. Seven mice with Gaucher’s disease received the test diet daily at a dose of 150 mg per kilogram of body weight, and seven mice with Gaucher’s disease that were matched for age and sex were given a base diet (control diet). The animals received the assigned diets for 2 months and were then euthanized for tissue and blood collection.

Statistical Analysis

The cohorts of patients with Gaucher’s disease and sporadic monoclonal gammopathy (MGUS or myeloma) and of healthy donors were compared with the use of nonparametric statistics, and P values were calculated. Two-tailed P values at an alpha level of 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Fisher’s exact tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were performed with the use of Stata software (StataCorp).

Results

Clonal Immunoglobulin in Gaucher’s Disease

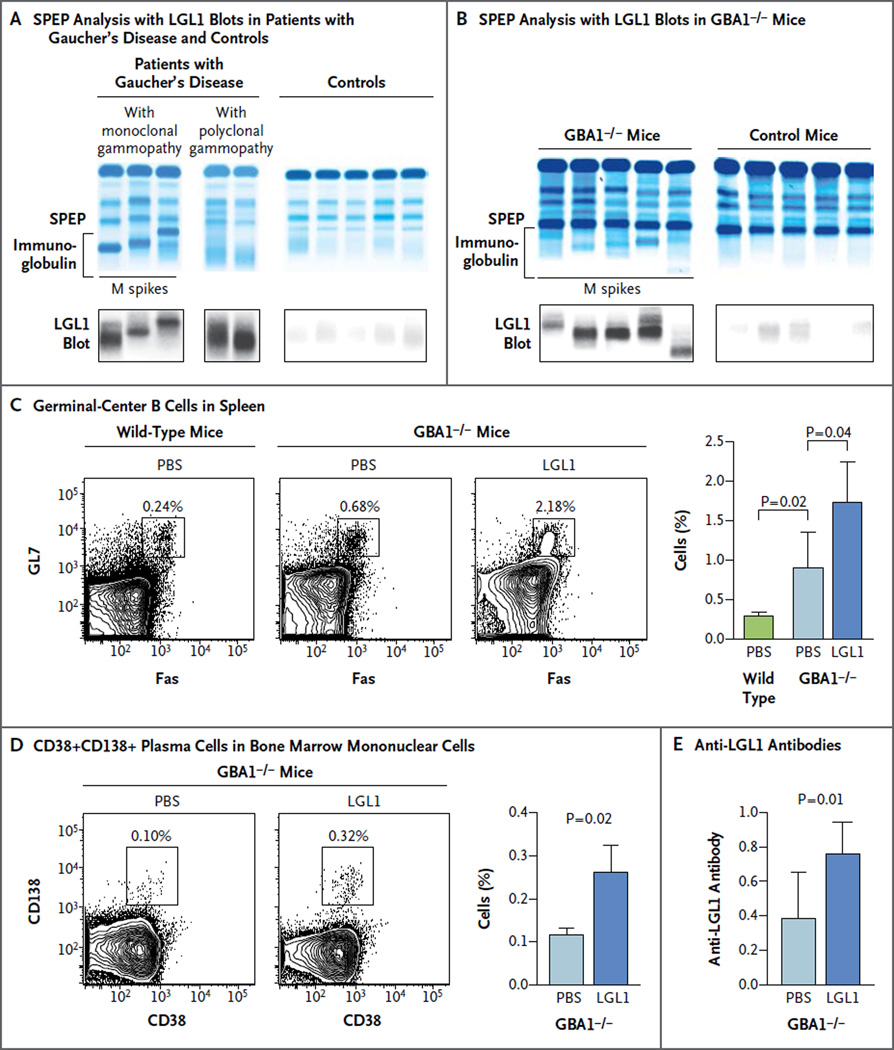

To evaluate whether the monoclonal immunoglobulin in the context of Gaucher’s disease reacts with LGL1, we analyzed the reactivity of clonal immunoglobulin against LGL1 with an antigen-specific immunoblot (Fig. 1A and 1B). Clonal immunoglobulin in 17 of 20 patients with Gaucher’s disease and in 6 of 6 GBA1−/− mice (which faithfully recapitulate type 1 Gaucher’s disease in humans)17 with monoclonal gammopathy was specific for LGL1. LGL1 reactivity was also observed for Gaucher’s disease–associated polyclonal gammopathy (Fig. 1A). In contrast, only low-level or background reactivity was detected in samples obtained from healthy donors or control mice.

Figure 1. Lipid Reactivity of Immunoglobulin in Patients and Mice with Gaucher’s Disease and in Controls.

Serum specimens obtained from patients with Gaucher’s disease–associated monoclonal gammopathy or polyclonal gammopathy and from healthy controls were analyzed by means of serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) (Panel A). The bracket shows the immunoglobulin component. In parallel, SPEP gel was blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane that was preincubated with lyso-glucosylceramide (LGL1) to identify LGL1-reactive immunoglobulins. SPEP was performed on serum specimens obtained from glucocerebrosidase- deficient (GBA1−/−) mice and from control mice that were matched for age and sex (Panel B). LGL1-specific blotting was performed simultaneously on serum specimens obtained from the GBA1−/− mice and the control mice. The M spikes in the serum specimens obtained from the GBA1−/− mice were reactive against LGL1. Representative contour plots show the percentage of FAS+GL7+ germinal-center B cells among total B cells (CD19+B220+) in splenocytes obtained from wild-type mice or GBA1−/− mice 7 days after three weekly injections with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or LGL1 (Panel C). The values above the insets indicate the percentage of cells in that particular gate. The bar graph shows the summary of the percentage of germinal-center B cells in splenocytes from wild-type mice and GBA1−/− mice 7 days after injection with PBS or LGL1. Data are means (from three mice); T bars indicate standard errors. A representative fluorescence- activated cell sorting plot (Panel D) shows the expression of CD38+CD138+ plasma cells in CD19−CD45lo bone marrow mononuclear cells (the gating strategy is shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix) obtained from GBA1−/− mice 7 days after PBS or LGL1 injection. Cumulative data show the percentage of CD38+CD138+ plasma cells. Data are means (from three mice); T bars indicate standard errors. The bar graph (Panel E) shows the presence of anti-LGL1 antibodies, with an optical density of 450 nm, in serum specimens obtained from GBA1−/− mice that had been injected with PBS or LGL1. Data are means; T bars indicate standard errors.

To show the capacity of LGL1 to mediate B-cell and plasma-cell activation in Gaucher’s disease in vivo, we hyperimmunized young GBA1−/− mice with LGL1. These mice already have a mildly higher level of Fas+GL7+ germinal-center B cells at baseline than the level in control mice (Fig. 1C). However, the injection of LGL1 led to a further increase in Fas+GL7+ splenic germinal-center B cells (Fig. 1C) as well as an increase in bone marrow CD38+CD138+ plasma cells (Fig. 1D, and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Injection of these mice with LGL1 — but not injection with an unrelated antigen (HEL) — led to the induction of anti-LGL1 antibodies in vivo (Fig. 1E, and Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). These data show the capacity of LGL1 to mediate B-cell activation in Gaucher’s disease and serve as an antigenic target in Gaucher’s disease–associated monoclonal gammopathy.

Clonal Immunoglobulin in Sporadic Gammopathies

The dysregulation of bioactive lipids and lipid-reactive T cells has also been observed in patients with sporadic myeloma.16,20 Therefore, we analyzed whether clonal immunoglobulin in sporadic MGUS and myeloma is also lipid-reactive. M spikes in 33% of the patients tested (22 of 66 patients) were LGL1-reactive (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). LGL1-reactive clonal immunoglobulins were cross-reactive against LPC (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no reactivity was observed in patients with polyclonal gammopathy that was not associated with Gaucher’s disease (Table 1, and Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 1.

Immunoglobulin Reactivity against Lysolipids.*

| Mouse Model or Human Cohort | Lysolipid Reactivity |

|---|---|

| no./total no. (%) | |

| Mice | |

| GBA1−/− mice | 6/6 (100) |

| Control mice | 0/10 |

| Humans | |

| Healthy donors | 0/25† |

| Patients with polyclonal gammopathy without Gaucher’s disease | 0/10 |

| Patients with Gaucher’s disease | |

| Normal immunoglobulins | 0/5 |

| Monoclonal gammopathy | 7/9 (78) |

| Polyclonal gammopathy | 10/11 (91) |

| Patients with sporadic monoclonal gammopathy | |

| MGUS or asymptomatic myeloma | 5/16 (31)† |

| Myeloma | 17/50 (34)† |

Data show the number of mice or patients with positive test results among the total number of mice or patients tested. Control mice were C57BL/6 and were matched for age and sex with glucocerebrosidase-deficient (GBA1−/−) mice. MGUS denotes monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Lipid reactivity was determined against both lyso-glucosylceramide (LGL1) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC).

Figure 2. Lipid Reactivity of Immunoglobulin in Sporadic Gammopathy.

Panel A shows the results of SPEP analysis, LGL1-specific blotting, and control blotting (with the use of human albumin as the control antigen) on serum specimens obtained from patients with monoclonal gammopathy, showing lipid reactivity or no lipid reactivity, and from healthy controls. Panel B shows the results of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC)–specific blotting, which was performed on serum specimens obtained from the same patients and healthy controls. Panel C shows the results of SPEP analysis, followed by LGL1, cardiolipin, lipid A, and diacylglycerol (DAG)–specific blotting on purified immunoglobulin obtained from patients with monoclonal gammopathy without Gaucher’s disease (sporadic monoclonal gammopathy), patients with Gaucher’s disease– associated monoclonal gammopathy, and healthy controls. Panel D shows the ligand-dependent enrichment of clonal immunoglobulin. Serum specimens obtained from three patients with lipid-reactive monoclonal gammopathy and three patients with lipid-nonreactive monoclonal gammopathy were incubated with control (C) or sphingosine (S)–coated sepharose beads; the bead-binding fraction was analyzed for the presence of clonal immunoglobulin by Western blot. The bottom panels show densitometric quantitation of bands performed with the use of ImageJ software. Panel E shows the ligand-dependent depletion of clonal immunoglobulin. Serum specimens from three patients with lipid-reactive monoclonal gammopathy and three patients with lipid-nonreactive monoclonal gammopathy were incubated with control or sphingosine-coated sepharose beads. The flow-through fraction was analyzed for M-spike depletion by means of SPEP. The bottom panels show densitometric quantitation of bands performed with the use of ImageJ software. The bar graph in Panel F shows the percent reduction in anti-LGL1 antibodies in serum specimens obtained from GBA1−/− mice after treatment with eligulstat (test diet), as compared with mice that received the control diet. Data are means; T bars indicate standard errors. The bar graph in Panel G shows the percent reduction in the M-spike intensity in serum specimens obtained from GBA1−/− mice after treatment with the test diet, as compared with mice that received the control diet. Data are means; T bars indicate standard errors.

Purified LGL1- and LPC-reactive clonal immunoglobulins did not react against cardiolipin, lipid A, or DAG in an antigen-specific immunoblot (Fig. 2C) or an ELISA with similar levels of purified immunoglobulin (Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The lipid reactivity of clonal immunoglobulins was verified by means of several approaches. Analysis of kappa and lambda lightchain isotypes of anti-LGL1 antibodies revealed a strong light-chain skew toward the involved clonal light chain only in patients with lipid-reactive M spikes (Fig. S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

LGL1-reactive immunoglobulins showed the same heavy- and light-chain specificity as the clonal immunoglobulin in immunoblotting (Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). The incubation of serum specimens with sphingosine-coated beads led to the specific enrichment of clonal immunoglobulin in the bead-binding fraction in patients with lipid-reactive M spikes, but not when the clonal immunoglobulin was not lipid-reactive (Fig. 2D). Similarly, the analysis of the bead flow-through fraction showed a specific depletion of M spikes only in patients with lipid-reactive M spikes (Fig. 2E).

F(ab′)2 fragments that were isolated from clonal immunoglobulins retained a capacity for antigen recognition that was similar to that for intact immunoglobulin in an ELISA and could be enriched by ligand-conjugated beads (Fig. S7 in the Supplementary Appendix), which indicated that the binding of these clonal immunoglobulins to ligands is F(ab′)2-mediated. The binding affinity of LGL1-reactive clonal immunoglobulins to antigen was estimated to be approximately 57×10−9 M, which is comparable to that reported for other antibodies (Fig. S8 in the Supplementary Appendix).

The cohort of patients with lipid-reactive gammopathies had a higher proportion of kappa light-chain, stage I myeloma and a lower proportion of intermediate- or high-risk cytogenetic factors than did patients who did not have lipid-reactive clonal immunoglobulins (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). These data show that the clonal immunoglobulin reacts with a bioactive lysolipid in nearly one third of patients with sporadic MGUS or myeloma, and the cohort of patients with lipid-reactive gammopathies may have a distinct clinical profile.

Discussion

Understanding the antigenic reactivity of clonal immunoglobulin not only has direct implications for antigenic origins of myeloma but also may lead to new strategies to prevent or treat clinical cancer by targeting the underlying antigen. Long-term antigenic stimulation may, in principle, also promote genomic instability in myeloma by engaging cytidine deaminases.21 In Gaucher’s disease– associated gammopathy, the reduction of LGL1 may be achieved by substrate-reduction therapies.22 Feeding eliglustat to GBA1−/− mice with clonal immunoglobulins led to a reduction in anti-LGL1 antibodies (Fig. 2F) as well as to a reduction of clonal immunoglobulin in vivo (Fig. 2G), which indicates that Gaucher’s disease–associated gammopathy can be targeted by the reduction of the underlying antigen. These data are also consistent with recent findings regarding a reduced risk of B-cell cancers with substrate reduction in another model of Gaucher’s disease.23

The dysregulation of lysolipids has also been described in the context of obesity.24 The risk of myeloma has been shown to be higher among obese persons than among persons of normal weight,1 and diet-induced obesity was recently shown to promote a myeloma-like condition in mice.25 Further studies in larger cohorts are needed to confirm clinical correlations and better define the genetics of lipid-reactive myeloma. Clinical studies are needed to assess whether altering the levels of bioactive lipids can influence the natural history of gammopathies with specificity for such lipids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants (CA135110, CA106802, and CA156689) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), by a grant (65932) from the NIH and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and by a Center of Excellence Grant in Clinical Translational Research from Genzyme.

We thank Lin Zhang for help with sample processing, and Joan Keutzer, of Genzyme, for providing eliglustat–formulated diets.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1046–1060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahota SS, Leo R, Hamblin TJ, Stevenson FK. Myeloma VL and VH gene sequences reveal a complementary imprint of antigen selection in tumor cells. Blood. 1997;89:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahota SS, Leo R, Hamblin TJ, Stevenson FK. Ig VH gene mutational patterns indicate different tumor cell status in human myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 1996;87:746–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zojer N, Ludwig H, Fiegl M, Stevenson FK, Sahota SS. Patterns of somatic mutations in VH genes reveal pathways of clonal transformation from MGUS to multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;101:4137–4139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakkus MH, Heirman C, Van Riet I, Van Camp B, Thielemans K. Evidence that multiple myeloma Ig heavy chain VDJ genes contain somatic mutations but show no intraclonal variation. Blood. 1992;80:2326–2335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vescio RA, Cao J, Hong CH, et al. Myeloma Ig heavy chain V region sequences reveal prior antigenic selection and marked somatic mutation but no intraclonal diversity. J Immunol. 1995;155:2487–2497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preuss KD, Pfreundschuh M, Ahlgrimm M, et al. A frequent target of paraproteins in the sera of patients with multiple myeloma and MGUS. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:656–661. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grass S, Preuss KD, Thome S, et al. Paraproteins of familial MGUS/multiple myeloma target family-typical antigens: hyperphosphorylation of autoantigens is a consistent finding in familial and sporadic MGUS/MM. Blood. 2011;118:635–637. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preuss KD, Pfreundschuh M, Fadle N, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of autoantigenic targets of paraproteins is due to inactivation of PP2A. Blood. 2011;118:3340–3346. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preuss KD, Pfreundschuh M, Weigert M, Fadle N, Regitz E, Kubuschok B. Sumoylated HSP90 is a dominantly inherited plasma cell dyscrasias risk factor. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:316–323. doi: 10.1172/JCI76802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson PN, Potter M. Induction of plasma cell tumours in BALB-c mice with 2,6,10,14-tetramethylpentadecane (pristane) Nature. 1969;222:994–995. doi: 10.1038/222994a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landgren O, Rajkumar SV, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among black and white women. Blood. 2010;116:1056–1059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry PK, Taddei T, vom Dahl S, Rosenbloom BE. Gaucher disease and malignancy: a model for cancer pathogenesis in an inborn error of metabolism. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:235–246. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.2013006145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekker N, van Dussen L, Hollak CE, et al. Elevated plasma glucosylsphingosine in Gaucher disease: relation to phenotype, storage cell markers, and therapeutic response. Blood. 2011;118(16):e118–e127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair S, Boddupalli CS, Verma R, et al. Type II NKT-TFH cells against Gaucher lipids regulate B-cell immunity and inflammation. Blood. 2015;125:1256–1271. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-600270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang DH, Deng H, Matthews P, et al. Inflammation-associated lysophospholipids as ligands for CD1d-restricted T cells in human cancer. Blood. 2008;112:1308–1316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mistry PK, Liu J, Yang M, et al. Glucocerebrosidase gene-deficient mouse recapitulates Gaucher disease displaying cellular and molecular dysregulation beyond the macrophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19473–19478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003308107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nooij FJ, Van der Sluijs-Gelling AJ, Jol- Van der Zijde CM, Van Tol MJ, Haas H, Radl J. Immunoblotting techniques for the detection of low level homogeneous immunoglobulin components in serum. J Immunol Methods. 1990;134:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90389-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun W, Abraham R. Modified diffusion blotting for rapid and efficient protein transfer with PhastSystem. Electrophoresis. 1989;10:249–253. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasagawa T, Okita M, Murakami J, Kato T, Watanabe A. Abnormal serum lysophospholipids in multiple myeloma patients. Lipids. 1999;34:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koduru S, Wong E, Strowig T, et al. Dendritic cell-mediated activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-dependent induction of genomic instability in human myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:2302–2309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mistry PK, Lukina E, Ben Turkia H, et al. Effect of oral eliglustat on splenomegaly in patients with Gaucher disease type 1: the ENGAGE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:695–706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlova EV, Archer J, Wang S, et al. Inhibition of UDP-glucosylceramide synthase in mice prevents Gaucher disease-associated B-cell malignancy. J Pathol. 2015;235:113–124. doi: 10.1002/path.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietiläinen KH, Sysi-Aho M, Rissanen A, et al. Acquired obesity is associated with changes in the serum lipidomic profile independent of genetic effects — a monozygotic twin study. PLoS One. 2007;2(2):e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lwin ST, Olechnowicz SW, Fowler JA, Edwards CM. Diet-induced obesity promotes a myeloma-like condition in vivo. Leukemia. 2015;29:507–510. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.