Abstract

Research suggests that parental warmth and positive parent–child interactions predict the development of conscience and empathy. Recent studies suggest that affective dimensions of parenting, including parental warmth, are associated with fewer behavior problems among children with high levels of callous-unemotional (CU) behavior. Evidence also suggests that CU behavior confers risk for behavior problems by uniquely shaping parenting. The current study examines reciprocal associations between parental warmth, CU behavior, and behavior problems among toddlers. Data from mother-child dyads (N=731; 49 % female) were collected from a multi-ethnic, high-risk sample at ages 2 and 3. CU behavior was assessed using a previously validated measure (Hyde et al. 2013). Models were tested using two measures of parental warmth, the first from direct observations of warmth in the home, the second coded from 5-min speech samples. Three-way cross-lagged, simultaneous effects models showed that parental warmth predicted child CU behavior, over and above associations with behavior problems. There were cross-lagged associations between directly observed parental warmth and child CU behavior, suggesting these behaviors show some malleability during toddlerhood and that parenting appears to reflect some adaptation to child behavior. The results have implications for models of early-starting behavior problems and preventative interventions for young children.

Keywords: Callous-unemotional, Behavior problems, Deceitful-callous, Parenting, warmth

In the last 15 years, a significant body of research has focused on the presence or absence of callous-unemotional (CU) behavior (e.g. lack of guilt and remorse, shallow affect) among antisocial youth (Frick et al. 2014; Frick and Viding 2009; Muñoz and Frick 2012). The presence of CU behavior delineates a subgroup of antisocial youth who appear distinct from their low-CU peers in etiology (a stronger genetic predisposition to antisocial behavior), prognosis (at increased risk of developing persistent antisocial behavior), and pattern of neurocognitive vulnerability (atypical affective and empathic processing, accompanied by functional and structural brain abnormalities in emotion processing and regulation areas of the brain) (see Frick and Viding 2009; Viding and McCrory 2012).

Two theoretical models have been put forward to explain the development of antisocial behavior associated with CU behavior. First, Kochanska and colleagues (Kochanska 1997; Kochanska et al. 2005) proposed that typical parental socialization efforts (e.g., effective discipline strategies) during early childhood produce negative emotional arousal in children, enabling conscience development and internalization of norms by school age. Optimal arousal levels are achieved through an interactive process between parenting and child temperament. ‘Fearlessness’ associated with CU behavior is thought to increase the level of arousal needed to experience transgression-related anxiety (Dadds and Salmon 2003). As such, children with CU behavior are thought to be more likely to develop aggressive or rule-breaking behavior. Second, Blair (2013) has proposed that amygdala hyporeactivity in response to cues of fear, distress, or sadness, underpins the development of CU behavior. Children are less able to associate actions that harm others with emotions of distress, producing deficits in empathic concern. More specifically, Blair argues that social norms are internalized via sanctions, whereas moral processing and empathy induction rely on successfully computing the distress of others.

In both models, a subgroup of children with CU behavior experience difficulties associating their behavior with negative emotional cues in the environment. As a result, their aggression towards others can continue unmodulated, placing them at risk of developing chronic and severe forms of antisocial behavior. While neither model specifies the cause of a child having a fearless temperament or low emotional responsivity, evidence from twin studies suggests that this may, at least in part, be due to a genetic predisposition (see Viding and McCrory 2012). This genetic predisposition could underpin individual differences in amygdala reactivity to signals of distress, autonomic reactivity, or ventromedial prefrontal cortex response to cues of punishment or reward (Blair 2013). However, neither genetic vulnerability nor differences in neurobiological function preclude the role of social factors in the environment, and particularly parenting (Viding and McCrory 2012). In fact, ‘getting the environmental conditions right’ might be especially important for those children who are more genetically vulnerable to develop CU behavior or conduct problems. Further, the notion that CU behaviors are somehow immutable or unresponsive to parenting practices is not borne out by the weight of the evidence (for a systematic review, see Waller et al. 2013).

An examination of the influence of very early parental warmth on children’s CU behavior may also represent a useful way to bridge two areas of literature that have, to date, remained somewhat separate. Indeed, identification of shared developmental precursors may enable alignment of the ‘CU traits literature’, as it relates to the extension of the adult construct of psychopathy (Frick et al. 2014), and a large body of literature examining individual differences in the development of guilt, empathy, and conscience among typically developing children (e.g., Kochanska 1997; Kochanska et al. 2005). In support of this notion, longitudinal research in preschool samples has demonstrated that a supportive parent–child relationship, characterized by mutual positive affect and cooperation can enhance internalization of prosocial norms and conscience development (e.g., Kochanska et al. 2005). Further, higher levels of maternal warmth demonstrated during infancy have been linked to increases in empathic responding (Kiang et al. 2004) and guilt (Kochanska et al. 2005). These findings suggest that parental warmth and positive involvement may be particularly important for the development of prosocial conceptualizations of relationships and children’s emotional responsiveness to others, both of which are related to the construct of CU behavior.

A large body of evidence supports the idea that high quality parenting in childhood, characterized by warmth, involvement, and sensitivity predicts a range of positive socioemotional and cognitive outcomes in early and middle childhood (e.g., Gardner et al. 2003; Maccoby and Martin 1983). Emerging evidence from prospective longitudinal studies also highlights the potential importance of positive affective dimensions of parenting to the development of CU behavior. For example, lower levels of positive reinforcement assessed in early/middle childhood (N=1,008, aged 3–10 years old; Hawes et al. 2011) and lower child-reported positive parenting in middle childhood (N=98, Frick et al. 2003; N=120, Pardini et al. 2007) predict increases in CU behavior over time. Further, lower levels of parental warmth were related to higher levels of CU behavior among incarcerated male adolescents, even after accounting for history of abuse and maltreatment (N=227, aged 12–19 years old; Kimonis et al. 2013). In a second type of study design, youth with high levels of CU behavior and high levels of antisocial behavior or behavior problems also appear to experience lower levels of positive parenting. This finding has been replicated cross-sectionally among clinic-referred boys (ages 3–10, Pasalich et al. 2011a), and longitudinally among a community sample of children (ages 3–4½ and 6½–8½ at follow-up, Kochanska et al. 2013) and high-risk girls (ages 7–8 and 12–13 at follow-up; Kroneman et al. 2011). Taken together, these studies suggest that dimensions of positive parenting, particularly parental warmth, may be important for understanding and reducing the development of CU behavior, or the behavior problems of children with high levels of CU behavior.

At the same time, few studies have considered the effects of a child’s CU behavior on the affective quality of the parent–child relationship, despite a large literature examining reciprocal parent–child processes in the development of antisocial behavior in general (Bell and Harper 1977; Patterson 1982; Shaw et al. 2003). Given that biological parents who raise their children are providers of both the genetic predisposition for affective and socioemotional processing deficits, and the affective quality of the early environment, it is intuitive that an emotionally unresponsive child might unintentionally undermine attempts at warmth, in particular from a parent who may share similar traits. In a recent study (3–10 years old, N= 1,008), Hawes et al. (2011) found that higher CU behavior predicted inconsistent parental discipline, decreased parental involvement, and increased use of corporal punishment over a 1 year period. The prediction of these dimensions of parenting by child CU behavior showed larger effects than those by behavior problems in general. In addition, Muñoz et al. (2011) examined longitudinal bidirectional relations between dimensions of parenting and youth antisocial behavior using cross-lagged models (12–16 years old; N=98). Less parental knowledge led to decreased parental control, specifically among youth with high levels of CU behavior. Taken together, the results of these two studies highlight the possible role of CU behavior in conferring greater risk for children developing antisocial behavior, by uniquely shaping dimensions of a parent’s caregiving practices.

However, no previous studies have tested cross-lagged reciprocal effects models, in which CU behavior, affective dimensions of parenting (e.g., warmth), and behavior problems are examined simultaneously across multiple time points. The dimensions of parenting assessed by Muñoz et al. (i.e., monitoring, control) may be more relevant to older samples of adolescents, whereas an examination of sensitive, nurturant, and warm parenting appears to be more salient in relation to understanding emerging behavior problems in younger children. The wide age range of the sample assessed by Hawes et al. (3–10 years old) makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the importance of parental warmth in early development and during specific developmental periods. Further, given that development of conscience and empathy appear to have their roots in the preschool years (e.g., Kochanska and Aksan 2006; Svetlova et al. 2010), a clearer picture is needed to better understand affective parent–child interactions occurring specifically during the late toddler and early preschool periods. These age periods are notable because they represent a time of rapid transition for children’s physical and cognitive abilities, as well as parents’ abilities to respond to such changes (Shaw and Bell 1993).

The current study therefore seeks to address a number of gaps in the literature and add to what is known about associations between early CU behavior, behavior problems, and dimensions of positive parental affect in very young children. In the current study, we examined reciprocal associations between parental warmth and child behavior during an earlier age period than in previous studies. Further, the children in our sample are all the same age at both assessment points, which provides a more precise picture of the nature of parent–child associations during this potentially important developmental period. It is noteworthy that in a previous study of the same sample, we found no prospective association between observed parental positive behavior support at ages 2 and 3 and later child CU behavior at ages 3 and 4 (see Waller et al. 2012a). However, the measure of positive behavior support in this earlier study assessed aspects of parental warmth, as well as parental proactiveness, structuring of the environment, and verbal communication (including periods of ‘neutral’ parent–child interactions). Thus, we hypothesized that a more precise index of parental warmth might be needed to investigate child–parent affective interactions specifically in relation to the development of CU behavior versus behavior problems (Waller et al. 2012a, p. 951).

Other strengths of the current study include the use of two different methods for assessing parental warmth to test reciprocal associations. First, our models included an observed measure of parental warmth, derived from global ratings of parent–child interactions following a 2–3 h visit in the home by an independent assessor. Second, we assessed parental warmth using a previously validated coding system for parental 5-min speech samples (see Pasalich et al. 2011b; Waller et al. 2012b), which provides an index of parental positive expression of emotion. The use of both measures enabled comparison of effects (and potential corroboration) for behavioral displays of warmth in a relatively holistic and naturalistic context (i.e., the home) versus parental expression of warmth during a verbally based and semi-structured task. Specifically, we wanted to examine how associations might differ for observed displays of warmth compared to parental expressions of warmth, positive affect, and empathic concern in general, which could be somewhat different to the parenting behavior displayed. Child CU behavior was assessed using a validated measure of deceitful-callous behavior, which has previously been shown to identify a subgroup of toddlers with more severe early behavior problems in this sample (Hyde et al. 2013), and was found to be predicted by observed and parent-reported measures of parental harshness (Waller et al. 2012a). Finally, an advantage of the current study is that we used reciprocal models to test the question of whether parental warmth was related to the early development of affective and empathic deficits (as indexed by CU behavior) controlling for behavior problems in general, while simultaneously assessing whether child CU behavior related to later parental warmth, again controlling for general behavior problems. We were thus able to test whether lower levels of parental warmth were specifically associated with CU behavior, or whether associations were accounted for by the presence of disruptive and externalizing behavior. Based on the extant literature, we hypothesized that parental warmth and child CU behavior would be reciprocally related over time, even when child behavior problems were controlled for within models.

Methods

Participants

Participants were mothers and children recruited as part of the large, ongoing Early Steps Multisite trial of the Family Check-Up parenting intervention (Dishion et al. 2008). During 2002/2003, families with a child between 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months of age were recruited from the Women, Infants, and Children Nutrition Program from the suburban Eugene, OR, urban Pittsburgh PA, and more rural Charlottesville, VA. Of the 1,666 families who had appropriate-aged children across sites, 879 met the eligibility criteria and 731 consented to participate. Eligibility criteria were defined as scoring one or more SD above the normative average on at least two of three screening measures. The screening measures were child behavior (including early-starting behavior problems), family problems (including maternal depression), and socioeconomic risk (including low education achievement). Ethical approval was granted by the IRB at each site and consent was obtained during annual assessments from the primary caregiver (see Dishion et al. 2008 for more details on the sample).

At the first assessment, children in the sample (N=731; 49 % female) had a mean age of 29.9 months (SD= 3.28 months). The sample was culturally diverse and across sites, primary caregivers self-identified as belonging to the following ethnic groups: 28 % African American, 50 % European American, 13 % biracial, and 9 % other groups. During the initial recruitment period, over 66 % of families across sites had an annual income of less than $20,000. The majority of primary caregivers were biological mothers (96 % at age 2 and 3). Children lived with both of their biological parents (37 %), a single/separated parent (42 %), or a cohabiting single parent (21 %). Finally, 41 % of primary caregivers had a high school diploma. Half the sample was randomly assigned to the intervention after the age 2 baseline assessment (for full details, see Dishion et al. 2008). Intervention status was used as a covariate in analyses.

Measures

All assessments were conducted in the home annually from age 2 with mothers, and if present, an alternative caregiver, such as a father or grandmother. Assessments began by introducing the child to age-appropriate toys and having them engage in free play while the mother completed questionnaires. Next, mother and child participated in various structured tasks, including a delay of gratification task and various teaching tasks. A 5-min parental speech sample was collected at the end of the home assessment. In a scripted prompt, interviewers asked parents, ‘please talk about your thoughts and feelings about your child, and how well you get along together’. Five-minute speech samples were used to code expressed parental warmth.

Demographics Questionnaire

A demographics questionnaire was administered at ages 2 and 3, which included questions about parental education and income (Dishion et al. 2008).

CU Behavior (Parent-Reported)

We assessed CU behavior using a measure of deceitful-callous behavior, which has been validated in a previous study using this sample (Hyde et al. 2013). The measure was constructed from parent-reported items from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Rescorla 2000), the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Robinson et al. 1980) and the Adult-Child Relationship Scale (Pianta 2001) at age 3. Items were chosen if they reflected an early lack of guilt, lack of affective behavior, deceitfulness, were related to the construct of CU traits, or were similar to items on the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick 2004). Items were examined in an exploratory factor analysis on half the sample, and a confirmatory factor analysis on the other half, as well as on alternate caregiver reports of these behaviors. The following five items loaded onto a single factor of deceitful-callous behavior: ‘child doesn’t seem guilty after misbehaving’, ‘punishment doesn’t change his/her behavior’, ‘child is selfish/won’t share’, ‘child lies’, and ‘child is sneaky/tries to get around me’ (see Hyde et al. 2013), which we refer to as CU behavior in the current study.

The five-item CU behavior measure demonstrated modest internal consistency at age 2 (α=0.57), which improved at age 3 (α=0.64). Internal consistencies are comparable with other measures of CU traits in older samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Frick et al. 2003; Hipwell et al. 2007). Further, our measure is similar to other brief assessments of CU traits comprising items from child behavior checklists, which have been validated as a construct that is separable from early behavior problems in samples of preschool children and that include behaviors that can be readily assessed during this developmental period (e.g., Willoughby et al. 2011, 2013). Nevertheless, the modest internal consistencies for our CU behavior measure at ages 2 and 3 should be considered along-side the findings of this study.

Behavior Problems (Parent-Reported)

Based on the overlap in content between the CU behavior measure and CBCL (i.e., 3 items were used from the CBCL to create the CU behavior scale), the Problem Factor of the ECBI (Robinson et al. 1980) was chosen as the measure of child behavior problems from ages 2 to 3. One item was used within the CU behavior measure (‘lies’) and was therefore removed from the Problem Behavior factor to avoid content overlap. The Problem Factor of the EBCI has previously been shown to demonstrate high reliability in the current sample from ages 2 to 4 (range, α=0.84 to 0.94; Dishion et al. 2008).

Expressed Parental Warmth

We used the positive subscale of the Family Affective Attitudes Rating Scale (FAARS; Bullock et al. 2005) to assess expressed parental warmth. FAARS is a macro-social coding system for parental speech samples that examines the beliefs and feelings expressed by a parent about their child, and a parent’s reports of how well they get along with their child. Each of the five items included in the positive subscale of FAARS is rated by coders on a 9-point Likert scale (e.g., ‘parent expresses statements of love/caring toward the child’ and ‘parent assumes or attributes positive intentions of the child’). Coding is based on coders’ global impressions of the speech sample and substantive information provided by parents about current attributions or behaviors relating to the child with the following scoring guidelines: 1 (no examples evidenced), 2–3 (some indication, but no concrete evidence), 3–4 (one or more weak examples), 5 (one concrete, unambiguous but unqualified example, or three or more weak examples of the same behavior/attribute), 6–8 (at least one concrete example and one or more weak examples of different behaviors/attributes), and 9 (two or more concrete, unambiguous examples) (for a detailed guideline for scoring, see the FAARS coding manual; Bullock et al. 2005).

Coding teams met weekly during training, and it took an average of 4 weeks to train teams. Coders had to achieve 80 % agreement on seven consecutive training samples after which, coders met weekly to prevent coder drift. Qualifying statements were coded as neutral (i.e., a positive statement followed by a qualifier, such as, ‘but’). The rating of an item between coders was considered an agreement if the scores were within 2 points (e.g., scores of 5 and 7 are an agreement, but scores of 5 and 8 are a disagreement). The total number of agreements were summed and divided by the total number of items to determine the percent agreement (80.7 % agreement at age 3). We created a mean score for the five positive subscale items to assess expressed parental warmth with acceptable internal consistency for the five items at both ages 2 and 3 (α=0.69 and α=0.67 respectively; see Waller et al. 2012b). The positive subscale of FAARS has previously been shown to demonstrate reliability and validity in the current sample, (Waller et al. 2012b), as well as in an older sample of clinic-referred children (aged 4–11 years old; Pasalich et al. 2011b), and a community sample of adolescents (aged 9–17 years old; Bullock and Dishion 2007).

Directly Observed Parental Warmth

A directly observed measure of parental warmth was developed from an adaptation of the Infant/Toddler Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (IT-HOME; Bradley and Corwyn 2002). The current study utilized examiner observation only for the Responsivity, Acceptance, and Involvement scales of the original IT-HOME. Further, other items assessing parent social skills and affect were developed for the Early Steps project and added to the original measure. For the purposes of the current study, seven items were chosen from this modified IT-HOME inventory, which captured global displays of parental positive affect and warmth towards their child: ‘parent responds verbally to child vocalizations’, ‘parent’s voice conveys positive feelings towards child’, ‘parent caresses or kisses child at least once during visit’, ‘parent responds positively to praise offered by visitor to child’, ‘parent is warm and friendly’, ‘parent seems to enjoy parenting’, and ‘parent seemed accepting of child’. Items were summed to create a measure of observed parental warmth with good internal consistency at ages 2 (α=0.73) and age 3 (α=0.77).

Analytic Strategy

To explore longitudinal, reciprocal associations between parental warmth, CU behavior, and behavior problems, autoregressive cross-lagged models were tested. In each model, scores for variables at age 3 were simultaneously regressed onto scores for variables at age 2. Within each age, variables were correlated to control for their overlap. All models included the following covariates: intervention group, child gender, child race, child ethnicity, parent education, and whether or not the parent was the child’s biological parent. In addition, because data was collected from multiple locations, project site was included as covariate. Separate models were computed to test associations between the two different methods of assessing parental warmth (expressed versus observed), CU behavior, and behavior problems, which enabled comparison of results according to the two assessment methods for parental warmth.

Of the 731 families who entered the study at child age 2, 659 (90 %) participated at age 3. Selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences in project site, race, ethnicity, gender, or child problem behavior (Dishion et al. 2008). Models were tested in Mplus 5.21 (Muthén and Muthén 2009) with a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach. Although there was some missing data at the two time points (n=651–731 for parent reported measures, n=559–693 for observed variables, including speech samples), FIML accommodates missing data and provides less biased estimates than listwise or pairwise deletion (Schafer and Graham 2002). Using FIML procedures, analyses included all participants except when they were missing data on an independent predictor that cannot be estimated with missingness (e.g., a covariate, such as poverty), resulting in an effective sample size of 728. The use of Mplus also permitted evaluation of multiple indices of model fit including Chi-square, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the significance of individual paths.

Results

First, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between variables were computed (Table 1). Stability between each construct was moderate from ages 2–3 (range r=0.32–0.48, p<0.001). There were significant correlations between CU behavior and behavior problems cross-sectionally and longitudinally (range, r=0.22–0.53, p<0.001). There were modest-moderate, significant cross-sectional and longitudinal bivariate correlations between the measures of parental warmth and both CU behavior and behavior problems (range r=−0.12–0.20, p<0.01). In addition, age 2 measures of child behavior were correlated with age 3 measures of parental warmth, although these associations were of larger magnitude and more likely to be significant between CU behavior and parental warmth than between behavior problems and parental warmth. Finally, bivariate associations between the different measures of parental warmth were modest (age 2, r=0.21, p<0.001; age 3, r=0.21, p<0.001), suggesting they were assessing different though somewhat related dimensions of parenting.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate cross-sectional and longitudinal correlations among study variables

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CU behavior age 2 | 0.00 | 0.12 | |||||||

| 2. CU behavior age 3 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.44*** | ||||||

| 3. Behavior problems age 2 | 14.18 | 6.49 | 0.31*** | 0.22*** | |||||

| 4. Behavior problems age 3 | 14.40 | 7.84 | 0.24*** | 0.53*** | 0.42*** | ||||

| 5. Expressed warmth age 2 | 3.95 | 1.48 | −0.12** | −0.12** | −0.13** | −0.12** | |||

| 6. Expressed warmth age 3 | 4.40 | 1.52 | −0.09* | −0.16*** | −0.06ns | −0.20*** | 0.32*** | ||

| 7. Directly observed warmth age 2 | 15.99 | 2.78 | −0.18*** | −0.17*** | −0.15*** | −0.14*** | 0.21*** | 0.20*** | |

| 8. Directly observed warmth age 3 | 15.89 | 2.97 | −0.20*** | −0.19*** | −0.15*** | −0.15*** | 0.17*** | 0.20*** | 0.48*** |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

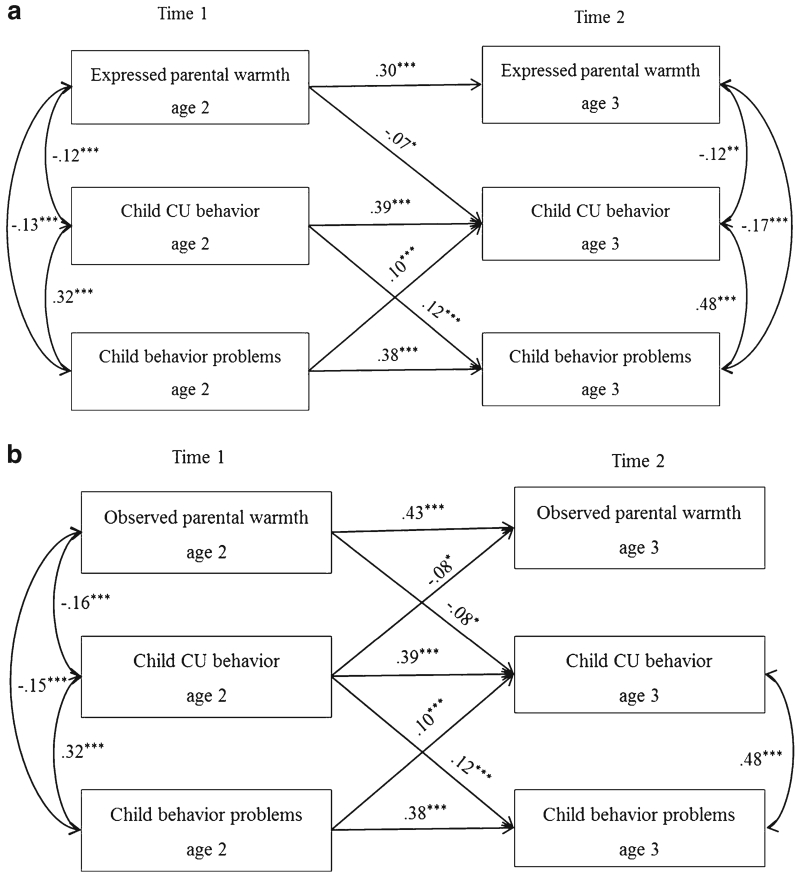

Second, two different three-way cross-lagged, simultaneous effects models were specified to test associations between CU behavior, expressed versus observed displays of parental warmth, and behavior problems at ages 2 and 3. Models included the following covariates: intervention group, child gender, child race, child ethnicity, parent education, whether or not the parent was the child’s biological parent, and project site. Standardized estimates of the cross-lagged pathways are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1. All variables showed stability over time (range β=0.30–0.43, p<0.001). CU behavior and behavior problems were reciprocally associated with each other over time (range β=0.10–0.12, p<0.01; c.f., Hyde et al. 2013). The model testing directly observed parental warmth showed good fit to the data (χ2= 7.05, df=12, p=0.32; CFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.016). There were significant associations between observed parental warmth and CU behavior (β=−0.08, p<0.05) and vice versa (β=−0.08, p<0.05). However, although there had been zero-order correlations between behavior problems and parental warmth, these variables were not significantly related when controlling for associations with CU behavior. The model testing expressed parental warmth showed acceptable fit to the data (χ2=50.53, df=12, p<0.001; CFI=0.94, RMSEA=0.066). There was a significant association between parental warmth at age 2 and CU behavior at age 3 (β=−0.08 p<0.05), but no cross-lagged effect. As before, although there had been zero-order correlations between expressed parental warmth and behavior problems, these variables were no longer significantly related when controlling for associations with CU behavior.

Table 2.

Standardized estimates of regression paths for models testing associations between child behavior and expressed versus directly observed parental warmth

| Expressed parental warmth | Directly observed parental warmth |

|

|---|---|---|

| Parental warmth age 2 → Parental warmth age 3 | 0.30*** | 0.43*** |

| CU behavior age 2 → CU behavior age 3 | 0.40*** | 0.39*** |

| Behavior problems age 2 → Behavior problems age 3 | 0.38*** | 0.38*** |

| Parental warmth age 2 → CU behavior age 3 | −0.07* | −0.08* |

| Parental warmth age 2 → Behavior problems age 3 | −0.06ns | −0.07ns |

| CU behavior age 2 → Parental warmth age 3 | −0.06ns | −0.08* |

| CU behavior age 2 → Behavior problems age 3 | 0.12** | 0.12** |

| Behavior problems age 2 → Parental warmth age 3 | 0.002ns | −0.06ns |

| Behavior problems age 2 → CU behavior age 3 | 0.10** | 0.10** |

Lower parent education predicted CU behavior at age 2 and lower observed warmth at ages 2 and 3. Non-white race associated with lower levels of directly observed warmth (ages 2 and 3)

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Fig. 1.

Cross-lagged reciprocal effects models between parental warmth, CU behavior, and behavior problems at ages 2 and 3. Note. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Only significant pathways shown. Lower parent education associated with deceitful-callous behavior at age 2 in both models, and lower age 2 observed parental warmth in model (b). Non-white race was associated with lower observed parental warmth at ages 2 and 3 in model (b)

As a more stringent test of potential effects of the intervention (i.e., rather than simply including intervention group as a covariate), we re-examined models in a multi-group path analysis for the two groups (i.e., intervention versus control). We constrained pathways between parental warmth and child CU behavior and behavior problems to be equal across groups and compared this to a multi-group model in which the same parameters varied across groups. We found no significant difference in fit for models testing directly observed (χ2 diff=3.89, df=9, p>0.90) or expressed measure of parental warmth (χ2 diff=5.76, df=9, p>0.70), suggesting that the model with paths constrained to be equal was more parsimonious, and thus that the effects we found were equivalent for families regardless of whether or not they received the intervention.

Finally, we re-computed analyses for parental warmth and CU behavior in two-way cross-lagged models. The pattern of findings was similar for associations between parental warmth and CU behavior as that reported for three-way models (see Table 2). To examine possible moderation of associations by behavior problems, we examined a multi-group path model. We split the sample into two groups comparing those who displayed high levels of behavior problems as indexed by the Eyberg Problem or Intensity factor, using previously validated cut-off scores and mirroring the criteria applied during recruitment for the study (Burns and Patterson 2001; Dishion et al. 2008). Specifically, children who scored above the 80th percentile on the Problem or Intensity Factors of the Eyberg at both ages 2 or age 3 were classified as ‘high’ (n=304) in their behavior problems, and all other children were classified as ‘low’ (n=344). We constrained pathways between parental warmth and CU behavior to be equal across groups and compared this to a model where parameters varied across groups. We found no significant difference in fit for models testing directly observed (χ2 diff=4.45, df=6, p>0.60) or expressed parental warmth (χ2 diff=6.48, df=6, p>0.30), suggesting that the more parsimonious model in which these paths were constrained to be equal across groups was most favorable, and thus that associations between parental warmth and CU behavior fit similarly regardless of whether children had high or low levels of behavior problems.

Discussion

This study examined reciprocal associations between parental warmth, child CU behavior, and behavior problems in a sample of high-risk toddlers. Parental warmth was assessed using two methods: expressed warmth via global coding of a speech sample and observed warmth via direct observation of parental warmth in the home. Based on an emerging literature examining associations between affective dimensions of parenting and CU behavior in children, it was predicted that parental warmth and CU behavior would be reciprocally related to each other over time, controlling for associations with behavior problems. There was support for the hypothesis with results suggesting that parental warmth may be particularly important to the early emergence of CU behavior specifically, rather than behavior problems in general. Child CU behavior was also found to predict parental warmth controlling for behavior problems (although only directly observed and not expressed parental warmth). There was therefore some evidence of reciprocal cross-lagged effects between parental warmth and early CU behavior.

In three-way models, regardless of the measurement approach, parental warmth predicted CU behavior, controlling for concurrent behavior problems and stability in child behavior and parental warmth. This finding is in keeping with other studies that have found that lower levels of positive parental affect, including positive parent–child relationship quality and parental warmth, are cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with higher levels of CU behavior in older samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Frick et al. 2003; Kimonis et al. 2013; Pardini et al. 2007). We also found a similar pattern of associations between parental warmth and CU behavior in two-way models when we confirmed that this process was equivalent for children with high versus low levels of behavior problems. Indeed, while we found a bivariate association between parental warmth and later child behavior problems, this association appeared to be accounted for by overlap between child behavior problems and CU behavior. Our findings therefore support the need for future studies to consider affective aspects of parent–child interactions and characteristics, independently of the effects of more overt forms of child externalizing behavior.

The findings of the current study are novel, because models tested longitudinal and simultaneous reciprocal effects between parental warmth and CU behavior, controlling for associations with behavior problems. Previous studies have been limited by testing associations between parental warmth, CU traits, and behavior problems using cross-sectional designs, assessing small, male samples with wide age ranges, or only examining behavior problems as an outcome in models (e.g., Pasalich et al. 2011a). The current findings fit with a broader line of research that has examined unique cognitive, socioemotional, and neurobiological characteristics of antisocial youth with CU behavior (see Blair 2013). In later childhood and adolescence, this subgroup of youth are at risk of more severe forms of antisocial behavior and demonstrate deficits in their behavioral and emotional responsiveness to cues of punishment and the distress of others (Frick and Viding 2009; Muñoz and Frick 2012). At the same time, older youth with CU traits appear sensitive to cues of reward. It has thus been proposed that a certain style of parenting in early childhood, characterized by high levels of parental involvement and warmth, cooperation, and mutual positive affect between parent and child could prevent early manifestations of a fearless or punishment-insensitive temperament resulting in empathy or conscience deficits (e.g., Kochanska 1997). The results of the current study support the notion that parental warmth in toddlerhood may help to reduce early displays of CU behavior, which may subsequently prevent a child developing more severe behavior problems.

Further, child CU behavior appeared to shape parental caregiving practices. Specifically, the findings in this study suggest that the emergence of affective deficits (i.e., CU behavior), rather than behavior problems in general, reduce the quality of positive affective interactions between parent and child, which fits well with previous studies reporting similar child effects among older samples of children and adolescents, (e.g., Hawes et al. 2011; Muñoz et al. 2011). It is interesting to note that early CU behavior in toddlers predicted fewer observed displays of parental warmth, controlling for earlier and concurrent behavior problems. It has been proposed that both parent and young child experience a mutually warm relationship as pleasurable, such that positive affect becomes positively reinforcing (MacDonald 1992). It is theoretically intuitive therefore, that if a parent finds that their attempts at warmth are not reciprocated, the frequency of their displays of warmth will decrease over time, which may be made more likely if they are themselves genetically predisposed to show low positive affect. Likewise, if an infant does not experience consistent warmth from a parent, the infant’s own positive emotional responsiveness to the parent may decrease. The current study provides some support for MacDonald’s (1992) theoretical proposal.

However, the cross-lagged effect was not replicated for expressed parental warmth, which was coded from speech samples. This differential pattern of findings could reflect differences in what is assessed by the two measures. The observed measure captures parental behavior directly and may be more independent of the outcome of CU behavior, which is reported on by parents. In contrast, the expressed measure reflects coding of the feelings, attributions, and attitudes the parent verbalizes about the child (Waller et al. 2012b), which may reflect potentially negative perceptions of their child’s CU behavior but also may not necessarily index their actual displays of warmth. On one hand, it is thus particularly interesting that it was the more independent observed displays of warmth that were predicted by child CU behavior. Further, these behavioral aspects of warmth provide a potentially useful target of intervention for the parents of toddlers at risk of behavior problems. The measure was derived from global ratings following an independent assessor spending 2–3 h in the family home and observing them during structured tasks (not used in construction of this measure), as well as during unstructured interactions. Thus, the measure appears to provide a holistic and naturalistic index of the positive emotional behavior of parents. On the other hand, the results obtained with the directly observed measure included items that were not part of the original IT-HOME inventory, and thus require replication in other samples.

Furthermore, the results from all models should be considered in the light of several other limitations. First, it is yet to be established if the current measure of CU behavior is prognostic of CU behavior in later childhood and adolescence, especially given that it contains a greater preponderance of deceitful and fewer unemotional items than CU traits scales for older ages (though note that ‘unemotional’ items were tested for this measure but did not load onto the scale; see Hyde et al. 2013). In addition, the current study is limited by the modest alphas obtained for the measure at both ages 2 and 3, which may indicate that aspects of callous-unemotionality may not be fully developed in young children until age 3.5 or 4 (Hyde et al. 2013, p. 359), affecting the reliability and validity of parent-reported measures. Replication of the current findings in future studies that use alternative methods to assess CU behavior, including observational tasks or experimental paradigms (e.g., Kochanska et al. 2002; Svetlova et al. 2010), or that use teacher reports, would strengthen conclusions that can be drawn about associations between early displays of CU behavior and parental warmth. Second, relatedly, parents reported on both CU behavior and behavior problems. On one hand, this may be problematic because distorted parental perceptions about their child could have resulted in over-reporting of negative aspects of child behavior while simultaneously reducing displays parental warmth, therefore accounting for the associations found. One the other hand, the prediction of parent-reported CU behavior by observed parental warmth, controlling for parent-reported problem behavior, suggests that the associations were not driven simply by parental negativity affecting both their beliefs about the child and behavior. In other words, inclusion of behavior problems in models acted as a control for parental negative perceptions.

Third, while there was moderate stability within constructs over time, the magnitude of associations between parental warmth and later child behavior, and child behavior and later parental warmth were modest. The modest effects across constructs could reflect method variance (i.e., observed versus parent-reported). However, the current study highlights the potential role of other (unobserved) factors in contributing to stability in both child CU behavior and parental warmth. Future studies are needed to further investigate the role of temperament or other indices of neurobiological functioning in relation to child behavior, and how this might interact with, or affect, parental warmth or positive parent–child interactions. For example, an emerging body of research suggests that CU behavior in boys is associated with deficits in attention to the eye region (Dadds et al. 2008, 2014; also see Hyde et al. 2014). Further, boys with high levels of CU behavior appear to show impaired eye contact during free interaction and emotion discussions with attachment figures (Dadds et al. 2011). In conjunction with the results of the current study, this emerging literature suggests that interventions, which help children to focus on salient emotional aspects of different social situations via eye contact, and potentially via increases in parental warmth, might be effective in reducing CU behavior and associated behavior problems (see Dadds and Rhodes 2008; Dadds et al. 2014). Finally, the current study focused on low-income children with multiple risk factors, including family risk (e.g., maternal depression, substance use), and early child problem behavior. For example, although this was not a clinic sample, many children displayed high levels of behavior problems. Specifically, aside from socioeconomic or family risk, families qualified for the original study if children scored in the clinical range on the Intensity or Problem Scales of the Eyberg Behavior Inventory, which comprised 44 % of the sample at recruitment (see Dishion et al. 2008; Robinson et al. 1980). In addition, although cut-off scores are yet to be established among children and adolescents, 17 % of the sample scored > 1 SD on our measure of CU behavior (see Hyde et al. 2013). Thus, it is unclear whether our results would be generalizable to children from higher-income families with fewer risk factors or lower levels of initial behavior problems.

The current study is the first to have examined concurrent and reciprocal associations between observed measures of parental warmth, CU behavior, and behavior problems over time, and in a very young sample of high-risk children. Results support the notion that the early, positive affective climate provided by parents appears to be reciprocally related to child CU behavior, over and above emerging behavior problems. The results also highlight the importance of evocative child-to-parent effects to the affective quality of interactions. Thus, the results emphasize the interactive and reciprocal nature of the development of early CU behavior. While testing intervention effects on CU behavior is beyond the scope of this paper, our findings may help emphasize the importance of targeting warm parenting for children high on early CU behavior. In fact, a previous study in the current sample demonstrated that a brief intervention was effective in reducing child behavior problems via improvements in parental positive behavior support (i.e., proactiveness, structuring, and clear communication; Dishion et al. 2008), which included aspects of warmth. Further, the presence of CU behavior did not moderate the effectiveness of the intervention from ages 2–4 (Hyde et al. 2013). Taken together these findings suggest that targeting parental positive behavior support, including parental warmth, may be effective in reducing both general behavior problems and CU behavior over time among high-risk children. However, it is yet to be established whether interventions targeting particular aspects of positive behavior support or other parenting behaviors (i.e., warmth or eye contact; see Dadds et al. 2014) can be effective in driving more change in children with behavior problems and high levels of CU behavior or if such interventions can directly reduce CU traits (see Hyde et al. 2014), which are both questions we hope to examine in future studies within this sample.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5R01 DA16110 from the National Institutes of Health, awarded to Dishion, Shaw, Wilson, & Gardner and a Green Templeton College PhD scholarship to Waller. We thank families and staff of the Early Steps Multisite Study. We also thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for valuable comments on an earlier version of this article.

Abbreviations

- CU

Callous-unemotional

- FAARS

Family Affective Attitudes Rating Scale

Footnotes

Conflict of interest No conflicts declared.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Waller, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA.

Frances Gardner, Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Essi Viding, Division of Psychology and Language Sciences, University College London, London, UK.

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Thomas J. Dishion, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Melvin N. Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Luke W. Hyde, Department of Psychology, Center for Human Growth and Development, Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bell R, Harper L. Child effects on adults. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:786–799. doi: 10.1038/nrn3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, Dishion T. Family process and adolescent problem behavior: integrating relationship narratives into understanding development and change. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:396–407. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802d0b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, Schneiger A, Dishion T. Manual for coding five-minute speech samples using the Family Affective Rating Scale (FAARS) Child and Family Centre, 195 W. 12th Avenue; Eugene, Oregon: 2005. p. 97401. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Patterson DR. Normative data on the eyberg child behavior inventory and sutter-eyberg student behavior inventory: parent and teacher rating scales of disruptive behavior problems in children and adolescents. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2001;23:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Rhodes T. Aggression in young children with concurrent callous-unemotional traits: can the neurosciences inform progress and innovation in treatment approaches? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2008;363:2567–2576. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds M, Salmon K. Punishment insensitivity and parenting: temperament and learning as interacting risks for antisocial behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(2):69–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1023762009877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, El Masry Y, Wimalaweera S, Guastella A. Reduced eye gaze explains “fear blindness” in childhood psychopathic traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(4):455–463. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816407f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Jambrak J, Pasalich D, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Impaired attention to the eyes of attachment figures and the developmental origins of psychopathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Allen JL, McGregor K, Woolgar M, Viding E, Scott S. Callous-unemotional traits in children and mechanisms of impaired eye contact during expressions of love: a treatment target? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12155. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick P. The inventory of callous-unemotional traits. 2004. Unpublished rating scale. [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick P, Kimonis E, Dandreaux D, Farell J. The 4-year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2003;21:713–736. doi: 10.1002/bsl.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. doi:10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Ward S, Burton J, Wilson C. Joint play and the early development of conduct problems in children: a longitudinal observational study of pre-schoolers. Social Development. 2003;12:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes D, Dadds M, Frost A, Hasking P. Do callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:507–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Pardini DA, Loeber R, Sembower M, Keenan K, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Callous-unemotional behaviors in young girls: shared and unique effects relative to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(3):293–304. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Cheong J, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:347–363. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, Burt SA. Improving treatment for youth with Callous-unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science: Commentary on Dadds et al., (2014) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12274. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Moreno A, Robinson J. Maternal Preconceptions About Parenting Predict Child Temperament, Maternal Sensitivity, And Children’S Empathy. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1081–1092. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Cross B, Howard A, Donoghue K. Maternal care, maltreatment and callous-unemotional traits among urban male juvenile offenders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(2):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9820-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: from toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:228–240. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Children’s conscience and self-regulation. Journal of Personality. 2006;74(Special Issue on Self-Regulation and Personality):1587–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Gross JN, Lin MH, Nichols KE. Guilt in young children: development, determinants, and relations with a broader system of standards. Child Development. 2002;73:461–482. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Forman DR, Aksan N, Dunbar SB. Pathways to conscience: early mother–child mutually responsive orientation and children’s moral emotion, conduct, and cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Boldt LJ, Yoon JE. Children’s callous-unemotional traits moderate links between their positive relationships with parents at preschool age and externalizing behavior problems at early school age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:1251–1260. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman L, Hipwell A, Loeber R, Koot H, Pardini D. Contextual risk factors as predictors of disruptive behavior disorder trajectories in girls: the moderating effect of callous-unemotional features. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011;52:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, Mussen PH, editors. Handbook of child psychology: vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development. Wiley; New York: 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K. Warmth as a developmental construct: an evolutionary analysis. Child Development. 1992;63:753–773. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz L, Frick P. Callous-unemotional traits and their implication for understanding and treating aggressive and violent youths. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2012;39:794–813. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz L, Pakalniskiene V, Frick P. Parental monitoring and youth behavior problems: moderation by callous unemotional traits over time. European Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20:261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 5. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Lochman J, Powell N. The development of callous-unemotional traits and antisocial behavior in children: are there shared and/or unique predictors? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:319–333. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich D, Dadds M, Hawes D, Brennan J. Callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems: an observational study. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011a;52:1308–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich D, Dadds M, Hawes D, Brennan J. Assessing relational schemas in parents of children with externalizing behavior disorders: reliability and validity of the family affective attitude rating scale. Psychiatry Research. 2011b;185:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G. Coercive family process. Castalia; Eugene: 1982. A social learning approach; III. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R. Student-teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, Eyberg S, Ross A. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1980;9:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J, Graham J. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Bell R. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby E, Nagin D. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols S, Brownell C. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: from instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development. 2010;81:1814–1827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, McCrory E. Why should we care about measuring callous-unemotional traits in children? British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):177–178. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.099770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion T, Wilson M. Do harsh and positive parenting predict reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2012a;53(9):946–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Validity of a brief measure of parental affective attitudes in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012b;40(6):945–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde L. What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(4):593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Waschbusch DA, Moore GA, Propper CB. Using the ASEBA to screen for callous unemotional traits in early childhood: factor structure, temporal stability, and utility. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33(1):19–30. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9195-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby MT, Mills-Koonce WR, Gottfredson NC, Wagner NJ. Measuring callous unemotional behaviors in early childhood: factor structure and the prediction of stable aggression in middle childhood. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10862-013-9379-9. doi:10.1007/s10862-013-9379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]