Abstract

Expression of the tumor suppressor protein BRCA1 is frequently lost in breast cancer patients, and the loss of its expression is associated with disruption of various critical functions in cells and cancer development. In the present study, we demonstrated that microarray analysis of cells with tumor suppressor candidate 4 (TUSC4) knockdown indicated critical changes such as cell cycle, cell death pathways and a global impact to cancer development. More importantly, we observed a clear cluster pattern of TUSC4-knockdown gene profiles with established homologous recombination (HR) repair defect signature. Additionally, TUSC4 protein can physically interact with E3 ligase Herc2 and prevents BRCA1 degradation via ubiquitination pathway. Knockdown of TUSC4 expression enhanced BRCA1 polyubiquitination, leading to BRCA1 protein degradation and a marked reduction in HR repair efficiency. Notably, ectopic expression of TUSC4 effectively suppressed the proliferation, invasion, and colony formation of breast cancer cells in vitro and tumorigenesis in vivo. Furthermore, knockdown of TUSC4 expression transformed normal mammary epithelial cells and enhanced the sensitivity of U2OS cells to the treatment of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Therefore, TUSC4 may act as a bona fide tumor suppressor by regulating BRCA1 protein stability and function in breast cancer.

Introduction

Loss of tumor suppressor gene in early lesion and establishment of enabling characteristics genomic instability are well-recognized steps towards cancer development (1, 2). Through genome-wide sequencing, many tumor suppressors were found frequently deleted or mutated in various cancers (3). Like all other deleted tumor suppressor gene, researchers first identified tumor suppressor candidate 4 (TUSC4; also known as nitrogen permease regulator-like 2) in a human lung cancer homozygous deletion region on chromosome 3p21.3. TUSC4 is highly conserved in species ranging from yeasts to humans (4). Sequence analysis demonstrated that TUSC4 possesses a protein-binding domain other than the nitrogen permease domain and that overexpression of TUSC4 reduces lung cancer proliferation both in vitro and in vivo (5). Homozygous deletions in chromosome 3p21.3 were also frequently detected in breast cancers (6). Indeed, with microarrays and pathway analyses, we have confirmed that loss of TUSC4 was associated with cancer development and multiple molecular functions such as cell cycle and cell death. More interestingly, we have identified that loss of TUSC4 expression resulted in a similar pattern to HR repair defects when clustered with our previously established HR defect gene signature profile (7).

Homologous recombination (HR) repair maintains genomic stability by mediating high-fidelity error-free repair on DNA double strands breaks (DSB) (8, 9). The deficiency of HR repair has been reported to promote cancer development and sensitize DNA damage-inducing therapy (10). The tumor suppressor protein BRCA1 is considered as one of the most important safeguards against breast cancer by protection of genome integrity and regulation of DNA damage repair, especially HR repair (11, 12). BRCA1 germline mutation carriers are more likely than non-carriers to have basal-like features with widespread genomic instability at both morphological and immunohistochemical levels (13). BRCA1-deficient cells exhibit enhanced sensitivity to irradiation and chemotherapies that induce DNA single- or double-strand breaks (14, 15), largely owing to their impaired capacity for HR repair (16). Therefore, the similar gene expression profiles between TUSC4 deficiency and HR repair defect raise the possibility that TUSC4 regulates HR repair through BRCA1. As expected, we have shown that the stability of BRCA1 and foci formations of BRCA1 in response to DNA damage was markedly reduced with knockdown of TUSC4 expression. Although BRCA1 expression is tightly regulated at both the transcriptional and protein level throughout the different stages of the cell cycle (17, 18), knowledge of how BRCA1 protein stability is regulated is still very limited. Our data further supported that TUSC4 physically interacts with Herc2, the E3 ligase of BRCA1 (19), thus blocking the binding between them and in turn stabilizing BRCA1 expression. Together, we have demonstrated that TUSC4 is a bona fide tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer and its function in suppressing genomic instability and cancer development may be at least in part through protecting the protein stability of BRCA1.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and plasmid

The U2OS, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-10A cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. McCoy's 5A medium (CellGro;10-050-CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum was used to maintain U2OS cells, RPMI 1640 medium (Corning; 10-104-CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum was used to culture MDA-MB-231 cells, and serum-free mammary epithelial growth medium (Clonetics; CC-3051) containing insulin, hydrocortisone, epidermal growth factor, and bovine pituitary extract was used to maintain MCF-10A cells. All cells were incubated under humidified conditions in 5% CO2. The pCMV5-3 ×Flag vector plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Funda Meric-Bernstam (The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center). The MD Anderson DNA Sequencing and Microarray Facility confirmed the identities of all plasmids.

Antibodies and reagents

An anti-TUSC4 antibody was purchased from Proteintech (10157-1-AP), an anti-BRCA1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-6954), and anti-Flag M2 (F3165) and anti-β-actin (A2066) antibodies were purchased from Sigma. Anti-Herc2 antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (612366). MG132 was purchased from EMD Biosciences (133407-82-6), and cycloheximide was obtained from Sigma (C7698). G418 was purchased from Sigma (A1720). Full-length TUSC4 was amplified using a TOPO TA cloning kit for subcloning (Invitrogen; 45064) with the sense primer 5′-AATGGGCAGCGGCTGCCGCA-3′ and anti-sense primer 5′-TCACTTCCAGCAGATGATGA-3′.

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies; 15596026) and reverse transcription was conducted using SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen), and BRCA1 was amplified using RT-PCR with the sense primer 5′-CAGCGATACTTTCCCAGAGC-3′ and anti-sense primer 5′-CTTGTTTCCCGACTGTGGTT-3′. Cyclophilin was used as internal control.

RNA interference

Stable knockdown of TUSC4 expression was established via RNA interference using lentiviral vector short hairpin RNA (Sigma; MISSION; NM660545). TUSC4 was targeted with a lentiviral particle of MISSION short hairpin RNA as well as MISSION nontargeted control particles. Western blotting was performed after transduction to confirm the knockdown efficiency, and puromycin was added to U2OS cell medium to maintain the TUSC4-knockdown specificity. For transient transfection, human TUSC4 siRNA was purchased from Thermo Scientific (On-Target; 10641), and the TUSC4 target sequences were GCAUCGAACACAAGAAGUA and GACCCAAGAUCACCUAUCA. Human BRCA1 siRNA was purchased from Thermo Scientific (On-Target; J-003461-09), and the BRCA1 target sequence was CAACAUGCCCACAGAUCAA. Human Herc2 siRNA was purchased from Thermo Scientific (On-Target; J-007180-09, J-007180-10, J-007180-11, and J-007180-12), and the Herc2 target sequences were 5′-GCACAGUAUCACAGGUA-3′, 5′-CGAUGAAGGUUUGGUAUUU-3′, 5′-GAUAAUACGACACAGCUAA-3′, and 5′-GCAGAUGUGUGCUAAGAUG-3′, respectively.

Immonuprecipitation and Immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation of Herc2, BRCA1, and TUSC4, U2OS cells were first transfected with an empty vector or FLAG-TUSC4 plasmids. After 72 h of transfection, G418 was added to the medium for selection purposes. After stable clones were isolated from the pool, whole cellular extracts were incubated with RIPA buffer as described previously (22), and the products were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG M2 Affinity gel (Sigma; A2220) for 8 h at 4 °C. After washing, the complexes were eluted with 3×FLAG peptide and evaluated using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). For immunoprecipitation of the binding between Herc2 and BRCA1, cell lysates were precleared with A/G Agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; SC-2003) and incubated with 1 μg of antibody at 4 °C overnight. Precipitates were then washed and suspended in 5× SDS buffer and submitted to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. For immunoblotting, after samples were separated using electrophoresis, membranes were blocked with 5% milk diluted in Tris buffer with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1h at room temperature. The primary antibody was diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline with sodium azide (Sigma; S227) and then incubated with the membranes for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, membranes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with secondary antibody. Finally, signals of the bound antibody were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare; RPN2232).

In vitro proliferation and PARP inhibition assays

MTT (Sigma; M5655) was used to evaluate the proliferation of cells. Briefly, cells were counted and seeded in a 96-well flat-bottomed plate. After 96 h, cells were incubated with MTT substrate (Sigma; 20 mg/ml) for 4 h, and the cultures were removed and replaced with dimethyl sulfoxide. The optical density was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. The colony formation assay was performed by seeding 200 cells in six-well plates. Olaparib and rucaparib were added to the culture medium, and the cells were compared with untreated control cells. Colonies were scored after 3 weeks. All experiments were repeated three times.

Microarray analysis

mirVana RNA isolation kit (Ambion) was used to isolate total RNA. Five hundred nanograms of total RNA were used with a Sentrix Human-6 Expression Bead Chip (Illumina) for labeling and hybridization. BeadArray Reader was used for chip scanning (Illumina). As described previously (7), the gene expression profile was subjected to normalization and log2 transformation. The NextGENe software program was used to identify genes whose expression differed in two clusters, and a t-test was used to separate genes with significantly different expression (P < 0.001). The Ingenuity Pathway Analysis system was used for gene enrichment analysis.

Homologous recombination repair and flow cytometry analyses

The plasmids DR-GFP, pCAGGS, and pCBASce were gifts from Dr. Maria Jasin (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). U2OS cells were first treated with TUSC4 and BRCA1 siRNA as well as control siRNA for 24 h. BRCA1-containing plasmids were then transfected into TUSC4-knockdown cells to induce re-expression of BRCA1. After 48-72 h, flow cytometry was performed to detect GFP-positive cells using a FACSCalibur and the CellQuest software program (Becton Dickinson). Three independent experiments were performed to obtain mean values and their standard deviations. Cell-cycle analysis was performed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Facility.

Tumor growth in nude mice and immunohistochemistry

Six-week-old female nude mice were used in this study. The MD Anderson Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the animal protocol. 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells with and without TUSC4 overexpression or 1 × 107 MCF-10A cells with and without knockdown of TUSC4 expression were injected to the mammary fatpads of mice. Tumors were measured from 1 week after MDA-MB-231 cells injection and monitored weekly, whereas MCF-10A tumors were observed 1 month after cell injection. At least five nude mice were used for each group. Human breast tissue samples (Biomax) were embedded in Xylene and 100%, 95%, 70%, 50% ethanol respectively for deparaffinization, slides were then incubated with TUSC4 antibody at 4° overnight followed by antigen retrieval. Then samples were processed and evaluated immunohistochemically under microscope after being dehydrated and stabilized.

Transfection and ubiquitination assay

U2OS cell transfection was conducted using Oligofectamine (Life Technologies; 12252-001). Plasmids encoding HA-tagged ubiquitin were transfected in U2OS cells with and without knockdown of TUSC4 expression. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer. Cell lysates were then incubated with Ni2+ beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) to pull down histidine-tagged BRCA1 with the beads. Precipitated BRCA1 protein was isolated using SDS-PAGE and detected using an anti-HA antibody (Sigma; ab18181).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with a two-tailed Student's t-test.

Results

TUSC4 expression is reduced in breast cancer and correlates with breast cancer progression

To characterize whether TUSC4 expression is associated with breast cancer, we performed Western blotting to measure the expression of TUSC4 in non-transformed breast cell lines, including HMEC, MCF-10A, and MCF-12A, and breast cancer cell lines with both luminal and basal subtypes (Fig. 1A). We observed that TUSC4 expression was markedly higher in the non-transformed cell lines than that in breast cancer cell lines. We also evaluated TUSC4 expression in normal breast tissue and breast carcinomas using immunohistochemical staining, and found that TUSC4 expression was lower in the tumors than that in matched adjacent normal breast tissue (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, The Cancer Genome Atlas-based analysis of mRNA expression in invasive breast carcinomas demonstrated a significant difference between the survival rates in patients with unaltered TUSC4 expression and those with downregulated TUSC4 expression (P = 0.000005). Specifically, the survival rate of 100 months was 24.7% in 889 patients with downregulation of TUSC4 expression (Z-score threshold, ±1), while the survival rate in these patients dropped sharply to 0% after 100 months. In comparison, the survival rate was 40% in patients with unaltered TUSC4 expression after 200 months, with a P value less than 0.0001 (Fig. 1C). Comparison of patients with upregulated and unaltered TUSC4 expression did not demonstrate any significant differences in survival rate (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results strongly suggested that low TUSC4 expression is associated with the cancer phenotype, indicating that TUSC4 may play an important role as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer patients.

Figure 1. Low TUSC4 expression level in breast cancer.

A. Lower TUSC4 expression levels was found in both luminal and basal types of breast cancer cell lines, while non-transformed breast cell lines (HMEC, MCF-10A and MCF-12A) exhibited higher TUSC4 level.

B. IHC staining indicated normal breast tissue (left) expressed higher TUSC4 protein level than breast cancer tissues (right).

C. 24.7% breast cancer patients showed low TUSC4 expression level, and the low TUSC4 level correlates with poor survival rate (p=0.00005, data adapted from cBio portal for Cancer Genomics).

D. TUSC4 knockdown microarray gene expression profiles were clustered with previously identified 230 homologous recombination defect gene signature, genes with p<0.001 and log ratio 0.1 were separated to generate heat map between TUSC4 knockdown cells and control cell lines.

To systematically evaluate the tumor-suppressive function of TUSC4, we performed microarray analysis comparing TUSC4-knockdown cell lines and control cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2). We then examined the differentially expressed genes in these cells using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis system (QIAGEN). Comparison of the TUSC4-knockdown and control cells ranked cancer as one of the top disease and disorder pathways, further suggesting that TUSC4 functions as a tumor suppressor gene (Fig. 1D). Additionally, high portion of genes in TUSC4-deficient gene signatures were involved in canonical pathways such as DNA damage response and breast cancer regulation (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Owing to the low TUSC4 expression in breast cancer and the association with poor breast cancer patient survival rates, we explored the role of TUSC4 in the development of breast cancer and the possible functional pathways that TUSC4 is involved in. It has been previously reported that multiple cancers have mutations in or epigenetically silenced HR related genes, which indicated potential association between HR repair deficiency and cancer development (15,16). Thus, we suspected that low expression of TUSC4 contributes to the deficiency of HR repair, which also drives genomic instability in breast cancer development. We performed a cluster analysis of a TUSC4-knockdown microarray signature with previously established HR repair deficiency (HRD) gene signatures (7). The heat map demonstrated that TUSC4-deficient cells formed a cluster with HRD gene signatures (Fig. 1E), whereas the control cells separated from TUSC4-knockdown samples. Considering the fact that the HRD signature described above was discovered under the condition of loss of tumor suppressor BRCA1, the results suggested a potential correlation and molecular similarity between TUSC4 knockdown cells and BRCA1-deficient HR repair deficiency.

TUSC4 knockdown impairs HR repair by downregulation of BRCA1 expression

The major conserved pathway used in mammalian cells to maintain genetic integrity and DNA fidelity is HR repair (20, 21). Here, we have identified an association between expression profile of TUSC4 knockdown and BRCA1 deficient HRD gene signature. We suspected that loss of TUSC4 will also affect the foci formation of BRCA1, so we carried out phenotypic examination to test whether TUSC4 is required for BRCA1 foci formation by immunostaining. We performed BRCA1 foci staining followed by IR and UV irradiation. TUSC4 knockdown significantly demolished the BRCA1 foci formation after irradiation, whereas control small interfering RNA (siRNA) did not affect the formation of BRCA1 foci (Fig. 2A, 2B). We further evaluated HR repair efficiency by the standard HR repair analysis system (22, 23) with TUSC4-deficient U2OS model cells. We found that TUSC4-knockdown cells had a significant decrease of HR reporter activity compared to control cells, which suggested impaired HR repair efficiency (Fig. 2C). We used BRCA1-knockdown cells as a positive indicator of homologous recombination repair to confirm the HR repair efficiency. TUSC4-knockdown cells presented comparative reduction in HR repair efficiency as BRCA1-knockdown cells, which were around 40-50% lower than that in control cells. To confirm that the defective HR repair efficiency was not caused by transfection efficiency or inaccurate efficiency from I-SceI, we reintroduced BRCA1 expression into the TUSC4-knockdown cells and observed a significant increase in HR repair efficiency over that in TUSC4-knockdown-only cells (P < 0.05).

Figure 2. TUSC4 knockdown reduced HR repair efficiency and BRCA1 protein expression level.

A. TUSC4 knockdown reduced BRCA1 foci formation after IR, while control cells didn't have such effect (NT). γ-H2AX indicated the efficiency of irradiation.

B. TUSC4 knockdown reduced BRCA1 foci formation after UV, while control cells (NT) didn't have such effect. p-RPA indicated the efficiency of irradiation.

C. TUSC4 knockdown significantly reduced HR repair efficiency compared to control (p<0.05), while reintroduction of BRCA1 expression into TUSC4-knockdown cells rescued the HR repair efficiency (p<0.05).

D. Western blotting confirmed TUSC4, BRCA1 knockdown and overexpression of BRCA1 after TUSC4 knockdown.

Surprisingly, we found that knockdown of TUSC4 expression reduced the BRCA1 protein expression (Fig. 2D), indicating that the decrease in HR repair efficiency in the TUSC4 knockdown cells may have resulted from abnormal BRCA1 protein expression. These results are consistent with our above findings that TUSC4-knockdown cells have HRD gene expression patterns similar to those in BRCA1-deficient cells which were used to generate our HRD gene signatures. These results revealed for the first time a novel function of TUSC4 in that disruption of its expression decreases BRCA1 expression and functions.

TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 protein stability

We next sought to determine how TUSC4 affects BRCA1 protein expression. To that end, we first sought to determine whether reduced BRCA1 protein expression after TUSC4 knockdown was caused by altered cell-cycle distribution because BRCA1 expression has known to be cell-cycle regulated. We carried out a cell-cycle analysis and did not observe a significant difference in G1-, G2/M-, or S-phase distribution between control and TUSC4-knockdown cells (Fig. 3A), indicating that decreased BRCA1 expression after TUSC4 knockdown was not resulted from the cell-cycle shift. To further determine whether such changes occur through transcriptional regulation, we performed quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction to measure the BRCA1 mRNA expression in control cells and cells with TUSC4 knockdown. We identified no significant BRCA1 mRNA differences after TUSC4 knockdown (Fig. 3B), thus ruling out the possibility that BRCA1 expression by TUSC4 was regulated at the mRNA level.

Figure 3. TUSC4 regulated BRCA1 stability via proteasome dependent pathway.

A. Knockdown of TUSC4 didn't significantly change the cell cycle distribution of U2OS cells compared to control cells. G1, G2/M and S phases cells were indicated by percentage of total cell numbers.

B. TUSC4 knockdown cells didn't show significant decrease of BRCA1 mRNA by qRT-PCR compared to control cells. The values of each column were normalized to the value of cyclophilin.

C. TUSC4 knockdown U2OS cells showed shortened half-life of BRCA1 level compared to control cells. All cells were treated with 1μM of CHX for 0 to 24 hours.

D. Curves of BRCA1 level normalized to 0h after CHX treatment, while blue curves indicated control cells, and red curves indicated TUSC4 knockdown cells.

E. Bar graph of BRCA1 half-life. Control cells have BRCA1 half-life about 20 hours, while TUSC4 knockdown cells have BRCA1 half-life about 5 hours.

Next, we sought to determine if TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 protein stability. To answer this question, we conducted BRCA1 protein stability experiments by treating control and TUSC4-knockdown U2OS cells with cycloheximide, for the purpose of blocking protein synthesis. As shown in Fig. 3C, TUSC4 knockdown reduced the half-life of BRCA1 from about 20 h to less than 6 h, suggesting that TUSC4 plays an essential role in stabilizing BRCA1 at the protein level (Fig. 3D, 3E). Additionally, to determine whether BRCA1 protein stability is regulated by TUSC4 via the proteasome pathway, we treated control and TUSC4-knockdown U2OS cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. As shown in Fig. 3F, MG132-based treatment restored the BRCA1 expression in cells with TUSC4 knockdown but only slightly increased the BRCA1 protein expression in control cells. This result suggested that TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 protein stability via the proteasome-dependent pathway.

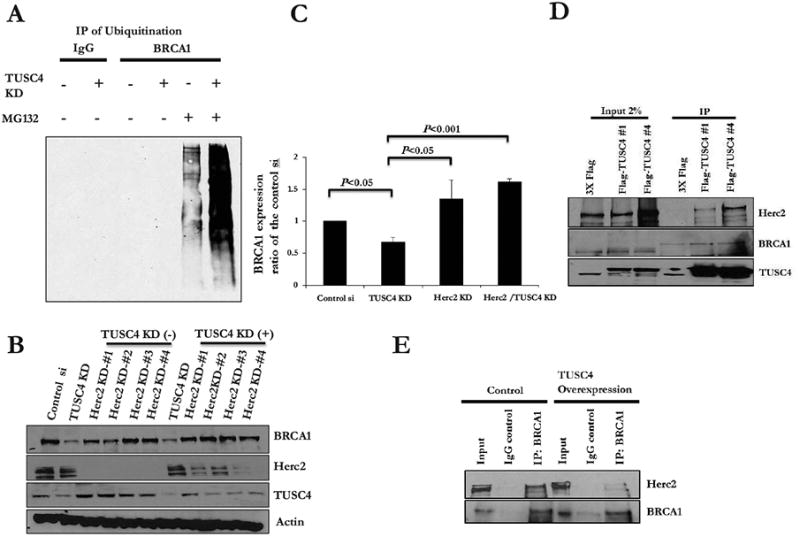

TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 protein stability via ubiquitination pathway

It has been previously reported that Herc2 is an E3 ligase that targets BRCA1 for degradation (18). To determine whether TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 stability via Herc2, we performed ubiquitination assay by transfecting hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin plasmids into cells with or without TUSC4 knockdown, followed by immunoprecipitation with control IgG or an anti-BRCA1 antibody. Surprisingly, we observed no signs of ubiquitination regardless of the TUSC4-knockdown status. However, after treatment with MG132, Western blotting for HA-tagged ubiquitin showed that TUSC4-knockdown cells underwent heavy ubiquitination, whereas control cells exhibited only a light polyubiquitination ladder (Fig. 4A), indicating that knockdown of TUSC4 expression caused a robust increase in BRCA1 protein polyubiquitination. We also confirmed previous findings that downregulation of expression of Herc2 led to increased expression of BRCA1 regardless of the presence of TUSC4 (Fig. 4B, 4C). Under both conditions, BRCA1 expression was markedly upregulated after depletion of Herc2.

Figure 4. TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 stability via ubiquitination pathway by blocking the binding of Herc2 to BRCA1.

A. TUSC4 knockdown increased ubiquitination level of BRCA1 compared to control cells (After MG132 enrichment for ubiquitination).

B. Herc2 knockdown rescued BRCA1 expression level, with and without the presences of TUSC4.

C. Bar graph indicated a significant BRCA1 reduction after TUSC4 knockdown (p<0.05), BRCA1 increases after Herc2 knockdown with TUSC4 presence (p<0.05), or without TUSC4 (p<0.001). All values were compared to control cells.

D. TUSC4 physically interacts with Herc2 but not BRCA1.

E. E. TUSC4 overexpression reduced the binding between BRCA1 and Herc2.

The next question to be answered was whether TUSC4 participates in ubiquitination of BRCA1 via Herc2 indirectly or stabilizes BRCA1 directly. We performed immunoprecipitation with established TUSC4-overexpressing U2OS cell lines to determine the relationships among TUSC4, BRCA1, and Herc2. Reciprocally, we found that TUSC4 physically interacts with Herc2 but not with BRCA1 (Fig. 4D), which strongly suggested that TUSC4 regulates BRCA1 stability via interaction with Herc2. Considering the previously reported binding functions of TUSC4 (24, 25), we suspected that TUSC4 may prevent physical interaction between BRCA1 and Herc2. The binding between these two proteins (19) has been previously described, so we performed further immunoprecipitation to determine whether overexpression of TUSC4 weakens this binding. As shown in Fig. 4E, endogenous Herc2 physically bound to BRCA1. Intriguingly, overexpression of TUSC4 interrupted the binding between Herc2 and BRCA1, indicating that TUSC4 may regulate BRCA1 stability by preventing physical interaction between BRCA1 and Herc2.

TUSC4 suppresses the tumorigenicity of human breast cancer cells

We have identified TUSC4 functions as tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer, possibly through positively regulating BRCA1. Next, we postulated that overexpression of TUSC4 also suppresses breast tumor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. To validate this, we compared the proliferation rate of the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 with or without TUSC4 overexpression. Colony formation assays indicated markedly reduced proliferation of the TUSC4-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Because TUSC4 effectively inhibits breast cancer cell growth in vitro, we further examined the effect of TUSC4 overexpression in a xenograft mouse model of breast cancer. We injected female mice with control or TUSC4-overexpressing MDA-MB-231cells into the mammary fatpads. We then monitored and measured tumor growth weekly. By week 6 after injection, 5 of 10 mice injected with TUSC4-overexpressing cells remained tumor-free, whereas all 5 mice injected with control 231 cells had large tumors (Fig. 5A, 5B; Table 1).

Figure 5. TUSC4 plays an important role as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer.

A. Colony formation assay indicated that normal U2OS cells are not sensitive to PARP inhibitor Olaparib (1μm) but TUSC4-knockdown cells exhibited increased sensitivity to Olaparib, the colonies were significantly reduced after the treatment (p<0.05).

B. Colony formation assay indicated that normal U2OS cells are not sensitive to PARP inhibitor Rucaparib (1μm) but TUSC4-knockdown cells exhibited increased sensitivity to Rucaparib, the colonies were significantly reduced after the treatment (p<0.05).

C. TUSC4 overexpression in MDA-MB-231cells (stable clones TUSC4 #7 and #13) significantly reduced the breast tumor growth in nude mice (p<0.05) compared to control 231 cells, the relative tumor size were indicated and compared as shown.

D. Tumor growth percentage of total injected mice by week after the injection of the MDA-MB-231 cells as well as two TUSC4 overexpression cell lines (#7 and #13).

Table 1. Tumorigenicity of Orthotopically Implanted Control and TUSC4-overexpression MDA-MB-231 cells.

5×106 cells from MDA-AB-231 control and two independent TUSC4-overexpressing MDA-AB-231 cell lines (TUSC4 #7 and TUSC4 #13) were injected per mouse into mammary tumor sizes were analyzed.

| Number of Mice with Tumors (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | |

| 231 Control | 3/5 (60) | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) |

| TUSC4-7 | 1/5 (20) | 2/5 (40) | 3/5 (60) | 3/5 (60) | 3/5 (60) | 3/5 (60) |

| TUSC4-13 | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) |

TUSC4 knockdown transforms normal mammary epithelial cells

Previous reports indicated that HR repair defect sensitizes cancer cells to DNA damaging drug (14, 15) and the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor (10,11). Thus, TUSC4 deficiency cells with HR repair defect are highly likely to be more sensitive to the treatment of PARP inhibitor, which can effectively inhibit the repair of single strand DNA break. To confirm this hypothesis, we performed colony formation assay in U2OS cell with TUSC4 knockdown after PARP inhibitor Olaparib and Rucaparib treatment, as well as control cells. As we expected, both drug significantly reduced the colony formation in TUSC4 knockdown cells compared the control cells (Fig. 5C, 5D). Additionally, we examined TUSC4 depletion to determine whether it initiates breast tumor development in a xenograft mouse model. We injected MCF-10A cells with stable knockdown of TUSC4 expression and the control cells into the mammary fatpads of female nude mice. Similarly to the procedure described above, we closely monitored tumor formation in the mice. Notably, tumors began to form in 3 of 10 mice injected with TUSC4-knockdown cells after 3 weeks, whereas no tumors formed in the control groups (Table 2). These results demonstrated that loss of TUSC4 expression alone is sufficient to initiate malignant transformation of immortalized nontransformed mammary epithelial cells, which is consistent with our hypothesis that TUSC4 functions as a bona fide tumor suppressor in breast cancer.

Table 2. Tumorigenicity of Orthotopically Implanted Control and TUSC4-Knockdown MCF10A cells.

1×107 cells from MCF-10A control and two independent TUSC4-knockdown MCF-10A cell lines (TUSC4 #1 and TUSC4 #4) were injected per mouse into mammary fat pads glands of 6-week-old female nude mice. Each cell line was injected in five different mice, and tumor sizes were analyzed.

| Number of Mice with Tumors (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 3 | Week 5 | Week 7 | Week 9 | |

| MCF10A Control | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) |

| TUSC4-1 | 0/5 (0) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) | 2/5 (40) |

| TUSC4-4 | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 1/5 (20) | 1/5 (20) |

Discussion

BRCA1 plays a key role in DNA damage responses including HR repair in an error-free manner. BRCA1 executes cellular functions in multiple complexes to safeguard genomic stability. In fact, loss of BRCA1 expression is reported to be associated with aggressive phenotypes of breast carcinoma (13, 26). However, very little is known about the mechanism of how BRCA1 expression is regulated during different stages of cancer development. Several previous studies demonstrated that BRCA1's stability is regulated via ubiquitination pathways (19, 27), but the network underneath this regulation remains unknown. We previously established HR repair-deficiency gene signatures and identified 230 genes that predict HR repair deficiency across tumor types (7). We surprisingly identified similar HRD gene signature patterns in TUSC4- and BRCA1-deficient cells which was used to generate HRD model, suggesting an association between these two proteins and shedding light for the exploration of regulation networks for TUSC4 and BRCA1. Furthermore, TUSC4-knockdown cells exhibited enhanced sensitivity to PARP inhibitor Olaparib and Rucaparib treatment, suggested the potential clinical usage of PARP inhibitors to treat TUSC4-defieicent breast cancer.

Previously reported data indicated that BRCA1 degradation is mediated by an ubiquitination pathway and this degradation in turn leads to proteasome-dependent BRCA1 degradation. Herc2 is the critical E3 ligase in this process. In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that expression of TUSC4 can positively regulate the stability of BRCA1 by preventing physical interaction between BRCA1 and its identified E3 ligase Herc2, which in turn protects BRCA1 from ubiquitination and degradation. Because TUSC4 knockdown is negatively correlated with BRCA1 protein expression and considering the previously reported protein-binding and -blocking capacity of TUSC4 between PDK1 and its co-activator Src (28), we suspected that TUSC4 plays a similar role in disrupting the interaction between BRCA1 and Herc2. Indeed, we found that TUSC4 physically interacts with BRCA1's E3 ligase Herc2 but not with BRCA1 itself. Overexpression of TUSC4 markedly weakened their interaction in immunoprecipitation experiments. This observation explained how TUSC4 overexpression can protect BRCA1 from degradation and greatly reduce the proliferation of breast cancer. Thus, the regulatory mechanisms of TUSC4 function in blocking the AKT pathway and stabilizing BRCA1 protein expression may be similar. TUSC4 does not have phosphorylation or E3 ligase activity according to functional domain analysis, so we speculated that its potential functions in the DNA damage response network and as a tumor suppressor are common mechanisms by the physical interaction, stabilizing or preventing activation of target proteins.

Additionally, our data demonstrated that depletion of TUSC4 led to diminished BRCA1 DNA damage foci after irradiation and weakened stability of BRCA1 protein expression. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that knockdown of TUSC4 expression may also affect the recruitment of BRCA1 to DNA damage foci. Furthermore, double knockdown of TUSC4 and BRCA1 in an HR repair assay reduced the HR repair efficiency more than knockdown of TUSC4 or BRCA1 expression alone did, suggesting that in addition to positive regulation for BRCA1 protein stability, TUSC4 may regulate HR function in BRCA1-independent pathways (data not shown).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jessica Tyler, Dr. Chun Li, Dr. Ju-Seog Lee and Dr. Hui-Kuan Lin (MD Anderson Cancer Center) for scientific discussions; we also thank Dr. Yun-Yong Park and Mr. Sang-Bae Kim (MD Anderson Cancer Center) for the microarray technical assistance.

Grant Support: This work was supported by The Department of Defense (DOD) Breast Cancer Research Program (BCRP) Era of Hope Scholar Award (W81XWH-10-1-0558) to S.Y- L.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg R. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell. 2011;144:5, 646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones RG, Thompson CB. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth. Genes & Dev. 2009;23:537–548. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu V, Zhou S, Diaz L, Kinzler K. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerman L, Minna J. The 630-kb lung cancer homozygous deletion region on human chromosome 3p21.3: identification and evaluation of the resident candidate tumor suppressor genes. The International Lung Cancer Chromosome 3p21.3 Tumor Suppressor Gene Consortium. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6116–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Wang F, Haraldson K, Protopopov A, Duh FM, Geil L, et al. Functional characterization of the candidate tumor suppressor gene NPRL2/G21 located in 3p21.3C. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6438–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabarovsky ER, Lerman MI, Minna JD. Tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p involved in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers. Oncogene. 2002;2:6915–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng G, Lin CJ, Mo W, Dai H, Park YY, Kim SM, et al. Genome-wide transcriptiome profiling of homologous recombination DNA repair. Nat Commun. 2014;3:3361, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levitt NC, Hickson ID. Caretaker tumour suppressor genes that defend genome integrity. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:179–86. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scully R, et al. Dynamic changes of BRCA1 subnuclear location and phosphorylation state are initiated by DNA damage. Cell. 1997;90:425–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alli E, Sharma VB, Sunderesakumar P, Ford JM. Defective repair of oxidative DNA damage in triple-negative breast cancer confers sensitivity to inhibition of Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3589–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell S, Kachnic L. Roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in homologous recombination, DNA replication fidelity and the cellular response to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5784–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James C, Quinn J, Mullan P, Johnston P, Harkin D. BRCA1, a potential predictive biomarker in the treatment of breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2007;12:142–150. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner N, Reis-Filho JS. Basal-like breast cancer and the BRCA1 phenotype. Oncogene. 2006;25:5846–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foray N, Randrianarison V, Marot D, Perricaudet M, Lenoir G, Feunteun J. γ-Rays-induced death of human cells carrying mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Oncogene. 1999;18:7334–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng CX, Wang RH. Roles of BRCA1 in DNA damage repair: a link between development and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:113–123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481:287–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruffner H, Verma M. BRCA1 is a cell cycle-regulated nuclear phosphoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7138–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin Y, Xu XL, Yang MC, Wei F, Ayi FC, Bowcock AM, Baer R. Cell cycle-dependent colocalization of BARD1 and BRCA1 in duscrete nuclear domians. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu W, Sato K, Koike A, Nishikawa H, Koizumi H, Venkitaraman AR, Ohta T. Herc2 is an E3 ligase that Targets BRCA1 for degradation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6348–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of homologous recombination: mediator and helicases take on regulatory functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:739–750. doi: 10.1038/nrm2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:712–720. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierce A, Johnson R, Thompson L, Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2622–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng G, Yim EK, Dai H, Jackson A, Burgt I, Pan MR, et al. BRTI1/MCPH1 links chromatin remodeling to DNA damage response. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:865–872. doi: 10.1038/ncb1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.K, Kawashima H, Ohtani S, Deng WG, Ravoori M, Bankson J, et al. The 3p21.3 tumor suppressor NPRL2 plays an important role in cisplatin-induced resistance in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9682–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayachandran G, Ueda K, Wang B, Roth JA, Ji L, et al. NPRL2 sensitizes human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells to cisplatin treatment by regulating key components in the DNA repair pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:8, e11994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulkes W, Stefansson I, Chappuis P, Bégin L, Goffin J, Wong N, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations and a basal epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:19, 1482–85. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Li J, Cheng D, Parameswaren B, Zhang S, Jiang Z, et al. The F-box protein FBXO44 mediates BRCA1 ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41014–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurata A, Katayama R, Watanabe T, Tsuruo T, Fujita N. TUSC4/NPRL2, a novel PDK-1 interacting protein, inhibites PDK1 tyrosine phosphorylation and its downstream signaling. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:182–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.