Abstract

Introduction

This survey characterizes viewpoints of cognitively intact at-risk participants in an Alzheimer Prevention Registry if given the opportunity to learn their genetic and amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) status.

Methods

A total of 207 participants were offered a 25-item survey. They were asked if they wished to know their apolipoprotein E (APOE) and amyloid PET status and if so, reasons for wanting to know, or not, and the effects of such information on life plans.

Results

One hundred sixty-four (79.2%) of the registrants completed the survey. Among those who were unaware of their APOE or amyloid PET results, 80% desired to know this information. The most common reasons for wanting disclosure were to participate in research, arrange personal affairs, prepare family for illness, and move life plans closer into the future. When asked if disclosure would help with making plans to end one's life when starting to lose their memory, 12.7% versus 11.5% responded yes for APOE and amyloid PET disclosures, respectively. Disclosure of these test results, if required for participation in a clinical trial, would make 15% of the people less likely to participate. Likelihood of participation in prevention research and the desire to know test results were not related to scores on brief tests of knowledge about the tests.

Discussion

These results suggest that stakeholders in AD prevention research generally wish to know biological test information about their risk for developing AD to assist in making life plans.

Keywords: Alzheimer, Prevention, Amyloid, PET, Apolipoprotein E, Survey, Clinical trials

1. Background

Owing to the advent of potentially disease-modifying drugs that are now in clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease (AD), there is great interest in identifying those in the prodromal [1] or preclinical [2] stage of the illness who may benefit most from such interventions. Identification of the most appropriate and willing subjects for these trials requires large outreach programs and prescreening activities by research sites. Family members of those afflicted with AD are among the largest segment of stakeholders who are most interested in possibly participating in these trials.

To accomplish the major task of identifying potential participants for prevention trials from the population, a number of centers have established registries, either using large scale web-based outreach, such as the Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative based in Arizona [3], [4], or more localized community efforts, such as the Alzheimer's Disease Prevention Registry at Duke University [5] and the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention [6].

Selection of prevention trial participants from such registries then rely on risk stratification. Diagnostic biomarker tests, such as amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, and genetic risk factor tests for apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype offer a means of reliably identifying people at significant risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, but it is unclear how potential and already enrolled research participants feel about their use if and when they personally learn of the results [7], [8]. Furthermore, ethical concerns have been raised [9], including enablement for pre-emptive suicide when people learn of risk information while they are still cognitively intact enough to make such plans [10]. On the other hand, there is also the potential benefit that learning about risk for the disease will motivate individuals to make important lifestyle changes to reduce risk.

Therefore, we carried out a survey of people in the Rhode Island Alzheimer Prevention Registry (RIPR) aiming to understand the viewpoints of cognitively intact people if given the opportunity to learn their APOE genetic status and amyloid PET status in a research setting. Although previous surveys have begun to address these topics in more general samples, our study examined individuals who were specifically interested in participating in prevention research and who had high rates of concern about developing Alzheimer's disease or dementia.

2. Methods

RIPR was established in 2012 with the support of an infrastructure grant under the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study with the goal of enlisting people in the community with normal cognitive and daily living function who are interested in participating in Alzheimer prevention research. The RIPR is included in the Rhode Island State Plan for Alzheimer's Disease [11] that was instituted in response to the National Plan to Address Alzheimer's Disease [12]. Participants are recruited by various community outreach efforts such as public presentations and advertisements as well as directly from the family and friends of patients attending the Rhode Island Hospital Alzheimer's Disease and Memory Disorders Center, a large hospital-based tertiary diagnostic and treatment center that receives referrals from the southeastern New England area.

Participants are invited to come for an office visit, for cognitive and APOE genetic testing, but this office visit is not required. Of the people who have enlisted in the RIPR, 90.2% have completed the office visit to date, with the remainder yet to be scheduled or refused due to inconvenience on the part of the participant. All participants sign an informed consent approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review Board. All participants are interviewed by phone, and basic demographic information is collected as well as information on exercise, diet, and family history of dementia. Medical and psychiatric history and medication usage data are collected as well. Exclusion criteria include diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or any dementia disorder, diagnosis of a major psychiatric condition that could impair cognition, including alcoholism by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria, diagnosis of mental retardation, Down's syndrome, or other major learning disability, education <6 years, non-English speaking, other neurologic disorder that affects cognitive (e.g., traumatic brain injury, stroke, Parkinson's disease), and age <45 years.

The Minnesota Cognitive Acuity Screen (MCAS) [13] is a cognitive screening instrument administered by phone to further exclude those likely to have dementia. Those in the range of mild cognitive impairment on this scale are not excluded. The MCAS has been shown to have good discrimination function between AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and normal subjects [14], [15] when used by telephone, and it has also been shown to have predictive ability for functional decline and conversion to dementia in one longitudinal study [16]. Among current registry participants, 16.7% are classified as MCI and the rest as being cognitively normal, using established cutoff scores for the MCAS.

The 207 people enrolled in the registry as of October 2014 were offered an anonymous 25-item survey to complete on paper or online. No standard educational materials were provided to participants before completing the survey. Questions were asked about whether participants knew or wished to know their APOE genetic status and amyloid PET status and if so, their reasons for wanting to know, or not, and the effects of such information on their beliefs and life plans.

Other questions assessed demographic items as well as their knowledge about APOE and amyloid PET. Knowledge questions about APOE status included these true or false statements about APOE: (1) Is a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. If you have this risk factor, you will definitely get Alzheimer's disease if you live long enough; (2) Is a genetic risk factor. If you have this risk factor, you are more likely to get Alzheimer's disease than those who do not; (3) Has not yet been established to be a risk factor for developing Alzheimer's disease; (4) Is commercially available; and (5) Is routinely done as part of the diagnostic evaluation for Alzheimer's disease performed by most physicians. Knowledge questions about amyloid PET included these true or false statements about APOE: (1) Is a brain imaging test that is used to diagnose dementia; (2) Is a brain imaging test that can be used to help rule out or exclude Alzheimer's disease as the cause of dementia; (3) Is a brain imaging test that can reliably demonstrate if there are significant amounts of amyloid plaques in the brain; (4) If showing no amyloid in the brain, means you will not develop Alzheimer's dementia; (5) Is commercially available; and (6) Is routinely done as part of the diagnostic evaluation for Alzheimer's disease performed by most physicians.

Before development of the survey questions, the medical literature on the topics of disclosure of APOE and amyloid PET status was reviewed by examining all articles in the English language from a search of PubMed over 10 years plus meeting abstracts during the past year. For sake of comparison, questions regarding reasons for wanting to know risk status were modeled after those previously used in the REVEAL study [17]. The final questions chosen for the survey, including their exact wording, were derived from consensus of the authors.

One hundred sixty-four people completed the survey (response rate 79.2%); 138 completed the survey by mail and 26 completed it online. Demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey sample (n = 164)

| Characteristics | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 64.7 ± 9.2 |

| Race (%) | 96.7 White |

| 2.5 Black | |

| 0.08 Mixed | |

| Gender (% female) | 73.9 |

| Education (%) | 0.1 Less than high school |

| 21.7 High school graduate | |

| 42.0 College graduate | |

| 35.7 Advanced degree | |

| Estimated annual income (%) | 20.8 <30,000 |

| 22.2 $30,000–$50,000 | |

| 41.7 $50,000–$100,000 | |

| 13.9 $100,000–$200,000 | |

| 1.4 >$200,000 | |

| Family history of Alzheimer's or dementia (%) | 71.8 At least one parent |

| 15.8 Both parents | |

| 7.6 Sibling | |

| Caregiver for family member (%) | 52.3 |

| You have memory problems worse than others your age that you know (%) | 27.5 |

| Others have expressed concern about your memory (%) | 21.2 |

| On a scale of 0 to 100, rate your risk of developing AD (SD) | 51.3 ± 25.6 |

| Rate your risk of developing AD (%) | 8.6 Unlikely |

| 64.8 Possible | |

| 25.3 Probable | |

| 1.2 Certain. I think I already have it. | |

| Rate your mood (%) | 32.7 Happy all the time/no depression |

| 60.5 Occasional feelings of depression | |

| 6.2 Depression most days | |

| 0.6 Severely depressed | |

| Rate your anxiety and worries | 6.8 Never anxious or worried |

| 78.4 Occasional anxiety and worries | |

| 14.8 Anxious and worried on most days | |

| 0.0 Severely anxious |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; AD, Alzheimer's disease.

3. Results

Participants who felt they had memory problems worse than other individuals of the same age they knew were 27.5%, and of these, 72.9% were concerned about the memory changes. Participants who felt it was unlikely that they had AD were 8.6%, whereas 26.5% felt they probably had AD. Self ratings of mood were happy all the time (32.7%), occasional feelings of depression (60.5%), depressed most days (6.2%), and severely depressed (.6%).

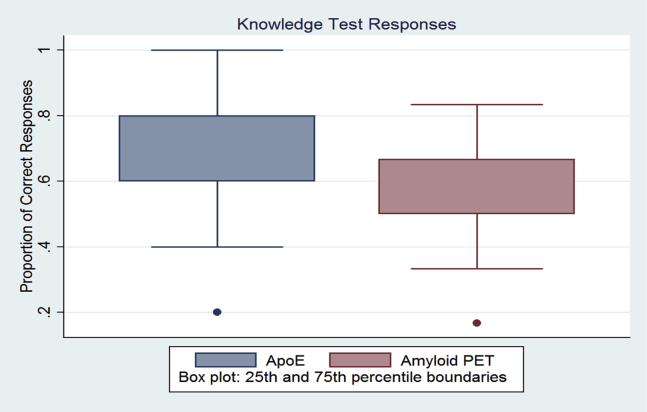

Respondents were asked five questions to test their knowledge about the APOE test and six questions to test their knowledge about amyloid PET. The proportions of correct response for each category of test are shown in Fig. 1. Over 70% of respondents were able to answer at least four questions correctly.

Fig. 1.

Knowledge test responses. Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; PET, positron emission tomography.

Ten had received disclosure of their APOE status and 13 had received disclosure of their amyloid PET status. Among those participants who knew their genetic risk or PET status, none reported feeling depressed, suicidal, or hopeless after receiving this information. Several of these individuals comprise a recent multiple case report that confirms this finding [18].

Among those who were unaware of their APOE status, 80.3% desired to know this information. Desire to know about APOE status was associated with higher perceived risk for developing AD (odds ratio [OR] = 3.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.25–8.47, P = .002). Self-reported memory complaints were correlated with less desire to know their status (OR = 0.21; 95% CI = 0.05–0.96, P = .04). The most common reasons expressed for wanting disclosure were to participate in AD research (75.9%), arrange personal affairs (74.1%), and move plans closer in the future (65.5%). Among those wishing this information, 12.7% would use the information to make plans for ending their life when they started to lose their memory, Table 2. The most common reasons for not wanting disclosure were concerns that they would feel anxious or depressed if they had the risk factor gene (40%), Table 3.

Table 2.

Reasons for wanting disclosure

| Reason | APOE, n = 116 (% of respondents) | Amyloid PET, n = 108 (% of respondents) |

|---|---|---|

| To participate and contribute to Alzheimer research | 75.9 | 73.2 |

| To arrange your personal affairs | 74.1 | 74.1 |

| To do things sooner than you had planned to do in the future | 65.5 | 58.3 |

| To prepare your spouse or children for your illness | 64.7 | 60.2 |

| To arrange your long-term care | 56.9 | 55.6 |

| To learn information for family planning | 56.9 | 52.8 |

| For relief that your chances are lower than you think | 49.1 | 46.3 |

| Curiosity/researched the finding | 43.4 | 51.9 |

| To confirm the feeling that you are already showing symptoms of the disease | 16.4 | 13.9 |

| To confirm the feeling that you are going to get the disease | 14.7 | 13.9 |

| To plan for ending your life when you start to lose your memory | 12.7 | 11.5 |

| Let it go/put it out of your mind | 8.6 | 5.6 |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; PET, positron emission tomography.

Table 3.

Reasons for not wanting disclosure

| Reason | APOE, n = 25 (% of respondents) | Amyloid PET, n = 25 (% of respondents) |

|---|---|---|

| It would frighten you or cause anxiety, if you had the risk factor gene or amyloid was elevated on PET | 40.0 | 28.0 |

| It would make you depressed, if you had the risk factor gene or amyloid was elevated on PET | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| You would not know what to do with the information | 36.0 | 32.0 |

| It might influence your life decisions or plans. | 24.0 | 32.0 |

| No interest in knowing | 20.0 | 28.0 |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; PET, positron emission tomography.

Among those who were unaware of their amyloid PET status, 80.6% desired to know this information. Demographic and psychological factors related to desire to know their status included perceived risk of having AD (OR = 1.03; 95% CI = 1.01–1.06, P = .001) or developing AD (OR = 8.53; 95% CI = 2.49–29.21, P = .001), whereas having an affected parent was inversely related (OR = 0.29; 95% CI = 0.12–0.73, P = .008). The most common reasons expressed for wanting disclosure were to participate in AD research (73.2%) and prepare spouse or children for their illness (60.2%). Among those wishing this information, 11.5% would use the information to make plans for ending their life when they started to lose their memory, Table 2. The most common reason for not wanting disclosure was feeling depressed if amyloid was elevated on PET (40%), Table 3.

Disclosure of APOE test results, if required for participation in a clinical trial, would make 43.7% of people more likely to participate and 14.8% of people less likely to participate. Disclosure of amyloid PET results, if required for participation in a clinical trial, would make 41.6% of people more likely to participate and 15.3% of people less likely to participate. The likelihood of participation and the desire to know APOE and PET results were not significantly related to total scores on the tests of knowledge.

4. Discussion

These survey results show that the vast majority of stakeholders in AD prevention research wish to know biological test information about their risk for AD, not only for the purpose of participating in research but also to assist in making life plans. A minority of potential participants would prefer not to be informed due to the potential anxiety and depression that may result from having a positive test result. Furthermore, providing such knowledge would have a more positive than negative overall effect on recruitment.

Although stakeholders at risk for AD are clearly interested in learning more about their individual risk, even the general population is keenly interested in knowing this information. For example, a general population survey of 314 individuals found that 79% of respondents stated that they would take a hypothetical genetic test to predict whether they would eventually develop AD [19]. In a survey module that was added to the Health and Retirement Study, among 1641 older adults, 60% indicated interest in testing that would help them learn about their AD risk [20]. In a cross-sectional telephone survey of 2678 adults across the United States and four European countries, 67% reported that they were “somewhat” or “very likely” to get a medical test to detect early AD if one became available [21].

Other studies focusing on more clearly at-risk samples in research settings such as ours have had similar findings. One survey of first-degree relatives of individuals with AD [22] examined beliefs and attitudes toward APOE predictive testing using hypothetical situations and found that the most important reasons for seeking testing were informing late-life decisions and planning future AD care. This study, as well as ours, also noted that perceived risk was strongly associated with desire to obtain genetic test information, whereas (as in the case of amyloid PET in our study) having a family history of AD reduced the interest in getting predictive testing. The reason for this latter observation as well as the observation that self-reported memory complaints were also related reduced interest in predictive testing is unknown but possibly due respondents already feeling that they know that they are at risk and are not in need of additional information.

These results are also very similar to those obtained from a survey performed online in 4036 people from the Alzheimer Prevention Registry based in Arizona [23]. Compared with our sample, respondents in this survey were younger (age ≥18 vs. ≥45 and mean 58.0 vs. 64.7 years), more often female (82.1% vs. 73.9%), less likely to have a first-degree relative with AD (61.3% vs. >71.8%), and more likely to be college educated (66.2% vs. 42.0%). Despite these differences as well as the method of registry enrollment (online vs. telephone or in person), their results produced similar trends. Like our sample, respondent understanding of biomarker testing was poorer for amyloid PET than for genetic testing (32.6% vs. 13.1%). A large majority (70.4%) felt that presymptomatic APOE genetic testing was important, and they would use the information for positive reasons such as beginning a healthier lifestyle (90.5%) and getting long-term insurance (76.3%). Similar results were seen for PET and spinal fluid biomarker disclosure: 80.2% of their respondents wanted to know biomarker results to reveal AD years before symptom onset, quite consistent with the rate of 80.6% in our sample who wished to know their amyloid PET status. Overall, our results extend the findings from the Arizona survey and suggest that desire to know risk status for AD is not restricted to highly educated and younger individuals.

Of particular concern, the Arizona survey found a minority of people who would use disclosure to “seriously consider suicide” (11.6% for APOE and 10.2% for biomarker disclosure). We asked a related but more specific question applying to pre-emptive suicide and found that a minority of respondents (12.7% for APOE and 11.5% for amyloid PET disclosure) would use the disclosure to “plan for ending your life when you start to lose your memory.” We agree with their conclusions that there is a need for greater public education on genetic and biomarker tests for AD and that psychological assessments for depression and counseling should be part of screening those who can or should be provided this information.

To address this concern, a standardized screening and disclosure process for amyloid PET has been successfully implemented in over 300 participants in the A4 secondary prevention trial so far [24]. Longitudinal assessment of the impact of such disclosure will be obtained in a substudy currently being conducted by telephone interview of participants.

Although it currently appears to be safe as well as generally acceptable or desirable for research participants in prevention studies to receive risk information, the ethics of disclosing genetic susceptibility information such as APOE genotype is still an area of some debate. First of all, the professional disclosing the information needs to be cognizant of the diagnostic and prognostic implications of the test results which imply risk but are not in themselves deterministic. Perhaps more importantly, the ethics depend on empirical evidence of how people actually perceive, recall, and communicate this type of complex risk information [9]. The conservative approach has been to withhold such information when acquired in research studies from individuals concerned about their risk for AD for fear of generating unwarranted stress and anxiety. This paternalistic view has been challenged, however, by results from the REVEAL study [25], indicating that disclosure of APOE genotyping results to a select group of adult children of patients with AD did not result in significant short-term psychological risks.

Although data from the REVEAL study are reassuring with regard to APOE disclosure, there is very limited information to date on the psychological impact on individuals who have had disclosure of their amyloid PET status, so controversy exists regarding whether such imaging information should be disclosed in clinical and research settings [26]. In a preliminary report from the University of Kansas Alzheimer's Prevention Program Exercise trial [27], disclosure of elevated amyloid status to 25 cognitively normal participants did not significantly increase anxiety or depression scores at baseline or at 6 months. Furthermore, these participants reported greater intent to change their daily diet and exercise. This same finding was also recently reported for a subgroup of our own registry participants [18].

Importantly, it should be noted that disclosure of risk information would serve to limit recruitment in only a minority of people who are interested in AD prevention research. Indeed, disclosure would serve to enhance likelihood of participation for 43% of people if given APOE information and 41.6% of people if given amyloid PET information in our sample. Similarly, knowing that one is at 50% increased risk for AD was found in one study using hypothetical scenarios to enhance recruitment into preclinical AD trials [28]. Another recent hypothetical clinical trial survey involving 132 cognitively normal people found that those assigned to a risk disclosure arm were 10% more likely to enroll than those in a nondisclosure arm. Furthermore, 96% of participants in the disclosure arm stated that they would want to learn their amyloid PET results [29].

Although the availability of prevention trials provides a reasonable incentive for people to undergo genetic [30] as well as amyloid PET risk testing [29] with disclosure of status, the fears and anxiety that a minority of people express about being given such information, as well as the possibility that the information could motivate suicidal ideation for some, points to the need for vigilance about psychological risk and efforts to minimize these risks through carefully designed disclosure protocols, such as the one currently being used in the A4 clinical prevention trial [24].

There are a number of limitations from this survey study that warrant consideration. The sample was highly selected to include only those older people who were specifically interested in participating in AD prevention research studies, so the results cannot be generalized to the larger population of people who are concerned about their risk for developing AD. In addition, limiting generalizability is the high educational status of the sample and the low number of minorities. A less well-educated group, and a more diverse group racially and ethnically, might have dramatically altered the results and conclusions of this survey. Although telephone and in-office cognitive tests were performed in registry participants to exclude dementia, we did not have the cognitive tests results of the respondents, so some of them likely had MCI and were not “normal.” Reduced interest in predictive testing among those with subjective complaints may have been driven by those with the greatest actual impairment, i.e., those with MCI.

Most importantly, the respondents to our survey were addressing hypothetical questions about their potential access to risk information. The registry does not provide this information to participants in actual practice. Therefore, it is unknown to what extent these viewpoints would translate to actual behaviors once the respondents would have been provided access to the information.

These data will hopefully stimulate further discussions in research circles and among stakeholder groups. Future research should involve a larger number of people after they have been informed of their amyloid PET status to provide additional insight on the effects of such knowledge on actual behaviors and decisions. Long-term studies on behavioral and psychological outcomes should be done to complement cross-sectional studies such as this one. There is also a need to better understand the long term and the immediate ethical issues surrounding AD risk disclosure.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: In addition to surveying stakeholders in Alzheimer prevention research from a registry, we searched PubMed over 10 years and meeting abstracts in the past year.

-

2.

Interpretation: Amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) and apolipoprotein E genotyping offer means of identifying people at risk of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD), but it is unclear how research participants feel about personal access to such test results. Stakeholders generally wish to know biological test information about their risk for developing AD to assist in making life plans as well as to decide on participation in prevention research. In a small minority, however, those plans may include pre-emptive suicide.

-

3.

Future directions: Future research should involve larger samples who have been informed of their amyloid PET status to provide additional insight regarding effects on actual behaviors and decisions. There is also a need to better understand the long term and the immediate ethical issues surrounding AD risk disclosure.

Acknowledgments

The Rhode Island Alzheimer Prevention Registry was supported by funds initially from an infrastructure grant to the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study, under 5U01 #AG10483-21, and it is currently supported by funds from Long Term Care Group who had no role in any aspect of the study or the article. The authors received no direct funds from any source for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling R.A., Aisen P.S., Beckett L.A., Bennett D.A., Craft S., Fagan A.M. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiman E.M., Langbaum J.B., Fleisher A.S., Caselli R.J., Chen K., Ayutyanont N. Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative: A plan to accelerate the evaluation of presymptomatic treatments. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(Suppl 3):321–329. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiman E.M., Langbaum J.B., Tariot P.N. Alzheimer's prevention initiative: A proposal to evaluate presymptomatic treatments as quickly as possible. Biomark Med. 2010;4:3–14. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero H.R., Welsh-Bohmer K.A., Gwyther L.P., Edmonds H.L., Plassman B.L., Germain C.M. Community engagement in diverse populations for Alzheimer disease prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:269–274. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowling N.M., Olson N., Mish T., Kaprakattu P., Gleason C. A model for the design and implementation of a participant recruitment registry for clinical studies of older adults. Clin Trials. 2012;9:204–214. doi: 10.1177/1740774511432555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence V., Pickett J., Ballard C., Murray J. Patient and carer views on participating in clinical trials for prodromal Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:22–31. doi: 10.1002/gps.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman M.B., Harkins K., Green R.C., Karlawish J. Using AD biomarker research results for clinical care: A survey of ADNI investigators. Neurology. 2013;81:1114–1121. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arribas-Ayllon M. The ethics of disclosing genetic diagnosis for Alzheimer's disease: Do we need a new paradigm? Br Med Bull. 2011;100:7–21. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis D.S. Alzheimer disease and pre-emptive suicide. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:543–549. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-101022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhode Island State Plan for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. 7-1-2013. 10-24-2015. Ref Type: Internet Communication.

- 12.National Plan to Address Alzheimer's Disease. 6-14-2013. 10-24-2015. Ref Type: Internet Communication.

- 13.Knopman D.S., Knudson D., Yoes M.E., Weiss D.J. Development and standardization of a new telephonic cognitive screening test: The Minnesota Cognitive Acuity Screen (MCAS) Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2000;13:286–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springate B.A., Tremont G., Ott B.R. Predicting functional impairments in cognitively impaired older adults using the Minnesota Cognitive Acuity Screen. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25:195–200. doi: 10.1177/0891988712464820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremont G., Papandonatos G.D., Springate B., Huminski B., McQuiggan M.D., Grace J. Use of the telephone-administered Minnesota Cognitive Acuity Screen to detect mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:555–562. doi: 10.1177/1533317511428151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremont G., Papandonatos G.D., Kelley P., Bryant K., Galioto R., Ott B.R. Prediction of cognitive and functional decline with the telephone-administered Minnesota Cognitive Acuity Screen. J Am Geriatr Assoc. 2016;64:608–613. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts J.S., LaRusse S.A., Katzen H., Whitehouse P.J., Barber M., Post S.G. Reasons for seeking genetic susceptibility testing among first-degree relatives of people with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17:86–93. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim Y.Y., Maruff P., Getter C., Snyder P.J. Disclosure of positron emission tomography amyloid imaging results: A preliminary study of safety and tolerability. Alzheimers Dement. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann P.J., Hammitt J.K., Mueller C., Fillit H.M., Hill J., Tetteh N.A. Public attitudes about genetic testing for Alzheimer's disease. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:252–264. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.5.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts J.S., McLaughlin S.J., Connell C.M. Public beliefs and knowledge about risk and protective factors for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(5 Suppl):S381–S389. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wikler E.M., Blendon R.J., Benson J.M. Would you want to know? Public attitudes on early diagnostic testing for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5:43. doi: 10.1186/alzrt206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts J.S. Anticipating response to predictive genetic testing for Alzheimer's disease: A survey of first-degree relatives. Gerontologist. 2000;40:43–52. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caselli R.J., Langbaum J., Marchant G.E., Lindor R.A., Hunt K.S., Henslin B.R. Public perceptions of presymptomatic testing for Alzheimer disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkins K., Sankar P., Sperling R., Grill J.D., Green R.C., Johnson K.A. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green R.C., Roberts J.S., Cupples L.A., Relkin N.R., Whitehouse P.J., Brown T. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:245–254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grill J.D., Johnson D.K., Burns J.M. Should we disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal individuals? Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2013;3:43–51. doi: 10.2217/nmt.12.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, DK, Vidoni, ED, Burns, JM, Bothwell, R, and Ramirez, O. Disclosure of amyloid imaging results in cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimer's Association International Conference Washington, D.C. 7-20-2015. Ref Type: Abstract.

- 28.Grill J.D., Karlawish J., Elashoff D., Vickrey B.G. Risk disclosure and preclinical Alzheimer's disease clinical trial enrollment. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grill, JD, Zhou, Y, Elashoff, E, and Karlawish, J. The requirement to learn amyloid status is not a barrier to enrollment in preclinical Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimer's Association International Conference Washington, D.C. 7-21-2015. Ref Type: Abstract.

- 30.Hooper M., Grill J.D., Rodriguez-Agudelo Y., Medina L.D., Fox M., varez-Retuerto A.I. The impact of the availability of prevention studies on the desire to undergo predictive testing in persons at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]