Abstract

Background:

Both lower urinary tract dysfunction and urinary symptoms are prevalent in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Although the significance of identifying and treating urinary symptoms in MS is currently well-known, there is no information about the real prevalence and therapeutic effect of urinary symptoms in patients with MS. The purpose of this study was to analyze the major symptoms and urodynamic abnormalities, and observe the therapeutic effect in different MS characteristics.

Methods:

We enrolled 126 patients with urological dysfunction who were recruited between July 2008 and January 2015 in Beijing Tian Tan Hospital, Capital Medical University and conducted overactive bladder system score (OABSS), urodynamic investigation, and expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Changes of urinary symptoms and urodynamic parameters were investigated.

Results:

Urgency was the predominant urinary symptom, and detrusor overactivity was the major bladder dysfunction. There was a positive correlation between EDSS and OABSS. Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) had lowest EDSS and OABSS. CIS exhibited significant improvements in OABSS, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), and bladder volume at the first desire to voiding and maximum bladder volume after the treatment (P < 0.05). Relapsing–remitting MS showed significant improvements in the OABSS, Qmax, and bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, maximum bladder volume and bladder compliance after the treatment (P < 0.05). Progressive MS exhibited significant increase in the bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, the detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate (PdetQmax), and bladder compliance after the treatment (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Urodynamic parameters examined are important in providing an accurate diagnosis, guiding management decisions of MS. Early and effective treatment may improve the bladder function and the quality of life at the early stages of MS.

Keywords: Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction, Multiple Sclerosis, Urinary Symptoms, Urodynamic

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that results in damages to the myelin sheaths of the nerves in the spinal cord and the brain.[1] MS is commonly diagnosed at the age range between 20 and 40 years and affects females 3–4 times more often than males.[2,3] Patients with MS are diagnosed with secondary lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) in common. MS patients with LUTD will seek urologic care because of troublesome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) at some point during their illness. Approximately 78% of all MS patients will develop LUTD during the disease.[4] LUTD is sustained by a complex alteration of the neurological control of the detrusor-sphincter function, resulting in detrusor overactivity, detrusor hypocontractility, and/or detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (DSD).[5] For MS patients, LUTD not only seriously affects the quality of life but also leads to the increasing risk for the upper urinary tract.[6,7] MS is divided into three subtypes according to the history and clinical characteristics: Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting, and primary progressive and secondary progressive. Every clinical type of MS has different clinical characteristics. Different clinical types of MS patients have different degrees of LTUD. Although the significance of urodynamic parameters examined and appropriately treated with LUTD in MS is currently well-known, there is not enough information about the real prevalence and impact of LUTD and therapeutic effect of urinary symptoms in patients with MS. Understanding the characteristics of LUTD in different clinical types of MS patients would be helpful in distinguishing MS type from the three types of MS and in assisting the management of patients with MS who have other medical conditions known to influence urinary function such as previous stroke, diabetes mellitus, spondylosis, and prostate hypertrophy. In addition, such understanding would offer an important insight into the pathophysiology of the MS complex and the mechanisms of LUTD in MS.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the predominant symptoms of the lower urinary tract observed in patients with MS, to evaluate urodynamic abnormalities, to detect the value of the urodynamic parameters in the clinical management of the three clinical types of MS, and to observe the therapeutic effect on urinary symptoms in different MS characteristics. This determination might help manage MS patients’ LUTD and improve the bladder function and the quality of life.

METHODS

This study was conducted in 126 patients consecutively with urinary symptoms secondary to MS who were recruited between July 2008 and January 2015 in Beijing Tian Tan Hospital, Capital Medical University. Inclusion criteria were represented by a diagnosis of MS according to the revised McDonald criteria (2010).[8] Cases with any one of the following conditions were excluded: (1) lack of ability to communicate, presence of LUTD secondary to cause other than MS (such as urinary tract infections, drugs interfering with detrusor function, urogenital prolapse in females, benign prostatic hyperplasia in men, urethral stricture), (2) a history of diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, or neurological diseases other than MS, and (3) a history of urethral, bladder, prostate, or pelvis surgery. The same neurologist diagnosed all patients with MS and divided them into three subgroups according to the history and clinical types: CIS; primary progressive; relapsing–remitting, and secondary progressive.

Disease severity was determined by the expanded disability status scale (EDSS).[9] In addition, to evaluate LUTS, overactive bladder system score (OABSS) was assessed at baseline 3 weeks after the start of treatment. Patients were also under urodynamic study for evaluation symptoms at baseline, and at 3 weeks after the start of treatment. The urodynamic parameters according to the International Continence Society (ICS)-standard (determination of residual urine by catheterization, cystomanometry in sitting position with filling the bladder at a physiological filling rate with 22°C physiological saline solution) were performed by one physician and one nurse.[10] Urodynamic parameters examined were conducted with a Medtronic Duet system; 9- and 6-Fr double-lumen bladder catheters were used for recording the intravesical pressure, and a 12-Fr rectal balloon catheter was used for measuring abdominal pressure. Urodynamic parameters including the electromyographic, Qmax (ml/s), bladder volume at the first desire to void (ml), maximum bladder volume (ml), PdetQmax (cmH2O), postvoid residual (PVR) (ml), and bladder compliance were recorded. Detrusor overactivity, detrusor hypocontractility, DSD bladder sensation, and low bladder compliance were defined in reference to the standardized report for the terminology of lower urinary tract function by the ICS.[11]

The present treatments for MS patients include immunomodulatory therapy (interferon), hormonotherapy (methylprednisolone), and behavioral therapy. Mean treatment period was 14.3 ± 5.5 days. Anticholinergic (tolterodine) was prescribed for patients with detrusor overactivity. Anticholinergic therapy, alpha-1 receptor blockers (tamsulosin), and intermittent catheterization were used in the patients with DSD. Intermittent catheterization was suggested for the patients with detrusor hypocontractility.

Ethics

All patients and their families understood the purpose, process, and potential risks of urodynamics and signed the informed consent; the study complied with the ethical principles. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tian Tan Hospital.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for quantitative variables. Pearson's or Spearman correlation analysis was used to determine the association between urodynamic parameters and MS patients’ disability status. We used the SPSS 11.5 software (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) to analyze statistically correlative parameters such as age, Qmax, PdetQmax, and PVR. The urodynamic parameters were expressed as mean ± SD. Paired t-test was used for corresponding parameters before/after treatment. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty-six patients with urinary symptoms secondary to MS were enrolled in the study. Ninety-eight of them were women (mean age 45.4 ± 10.5 years) and the rest were men (mean age 41.5 ± 9.0 years). According to the records, they were diagnosed with clinical isolated syndrome CIS (n = 30), relapsing–remitting MS (n = 64), progressive MS (n = 32) including primary progressive MS (n = 10), and secondary progressive MS (n = 22). The mean duration of MS was 8.24 ± 8.07 years and the mean duration of LUTS was 6.46 ± 7.58 years.

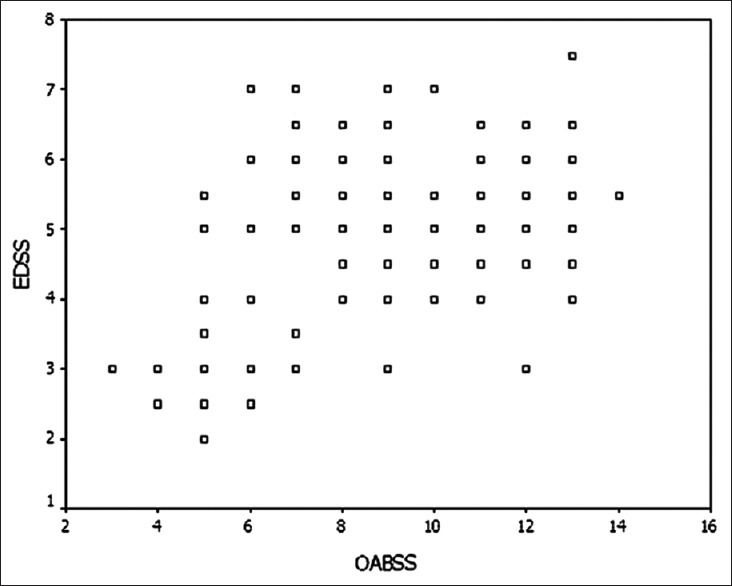

Urgency was the predominant urinary symptoms, followed by frequency, urge incontinence, stress incontinence, hesitancy, feeling of incomplete emptying, dysuria, and mixed incontinence [Table 1]. The mean OABSS was 8.62 ± 2.67 for MS patients with urinary complaints. Mean patient disability, expressed as an EDSS, showed a mean value of 4.85 ± 1.31. There was a positive correlation between EDSS and OABSS. The presence of urologic symptoms was associated with severe disability as assessed with EDSS (r = 0.477, P < 0.05) [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Urinary symptoms of patients

| Urinary symptom | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Urgency | 81 (64.3) |

| Frequency | 62 (49.2) |

| Urge incontinence | 32 (25.4) |

| Stress incontinence | 21 (16.7) |

| Hesitancy | 19 (15.1) |

| Feeling of incomplete emptying | 18 (14.3) |

| Dysuria | 17 (13.5) |

| Mixed incontinence | 8 (6.3) |

Figure 1.

Correlation between expanded disability status scale (EDSS) and overactive bladder system score (OABSS) (r = 0.477, P < 0.05).

In the present study, urodynamic abnormalities were observed in 85 patients (67.5%). However, 41 patients with MS (32.5%) had a normal bladder. For MS patients, detrusor overactivity was the predominant bladder dysfunction. The other urodynamic abnormalities include DSD, detrusor hypocontractility, and poor compliance bladder [Table 2]. Fifty-eight of 81 patients (71.6%) with urgency were diagnosed as detrusor overactivity.

Table 2.

Urodynamic patterns of patients, n (%)

| Urodynamic type | CIS | R−R MS | P MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| DO | 6 (20.0) | 30 (46.9) | 13 (40.6) |

| DSD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| PC | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (6.3) |

| DH | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 6 (4.8) |

| DO + DSD | 3 (10.0) | 12 (18.8) | 8 (25.0) |

| DO + PC | 0 (0) | 2 (3.1) | 2 (6.3) |

| DO + DH | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (6.3) |

DO: Detrusor overactivity; DSD: Detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia; PC: Poor compliance; DH: Detrusor hypocontractility; CIS: Clinically isolated syndrome; R−R MS: Relapsing−remitting multiple sclerosis; P MS: Progressive multiple sclerosis.

CIS patients had significantly lower EDSS and OABSS than relapsing–remitting MS (P < 0.01) or progressive MS (P < 0.01). However, there was no statistically significant difference between relapsing–remitting MS and progressive MS (P = 0.155) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the OABSS and EDSS among CIS, R−R MS and P MS

| Items | CIS | R−R MS | P MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 45 | 25 |

| OABSS | 5.63 ± 1.40* | 9.52 ± 2.18† | 9.63 ± 2.42 |

| EDSS | 2.98 ± 0.59‡ | 5.48 ± 0.78§ | 5.61 ± 0.75 |

*P<0.01, CIS compared with R-R or progressive MS; †P>0.05, R−R MS compared with progressive MS; ‡P<0.01, CIS compared with R−R MS or P MS; §P>0.05, R−R MS compared with P MS. OABSS: Overactive bladder system score; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; CIS: Clinically isolated syndrome; R−R MS: Relapsing−remitting multiple sclerosis; P MS: Progressive multiple sclerosis.

For CIS patients, the differences in the OABSS, Qmax, and bladder volume at the first desire to voiding and maximum bladder volume before and after the treatment were statistically significant (P < 0.05). However, there was a weak change in the PVR, bladder compliance, and the PdetQmax. For relapsing–remitting MS patients, the differences in the OABSS, Qmax, and bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, maximum bladder volume and bladder compliance before and after the treatment were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The differences in the PVR and the PdetQmax were not statistically significant. For progressive MS patients, the differences in the bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, the PdetQmax and bladder compliance before and after the treatment were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The differences in the OABSS, Qmax, maximum bladder volume, and PVR were not statistically significant [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of the parameters before and after treatment for MS

| Items | CIS | R−R MS | P MS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | t | P | Before | After | t | P | Before | After | t | P | |

| OABSS | 5.63 ± 1.40 | 4.33 ± 0.76 | 6.966 | 0.000 | 9.52 ± 2.18 | 8.95 ± 2.05 | 2.466 | 0.016 | 9.63 ± 2.42 | 9.56 ± 2.24 | 0.360 | 0.721 |

| Qmax (ml/s) | 16.5 ± 3.2 | 17.3 ± 2.6 | −2.274 | 0.031 | 13.3 ± 4.4 | 15.0 ± 3.4 | −6.834 | 0.000 | 11.5 ± 2.7 | 11.6 ± 3.1 | −0.369 | 0.715 |

| BVFD (ml) | 128.5 ± 29.2 | 145.1 ± 16.6 | −5.064 | 0.000 | 123.7 ± 36.0 | 137.0 ± 29.9 | −6.320 | 0.000 | 109.2 ± 24.3 | 131.7 ± 18.1 | −6.210 | 0.000 |

| MBV (ml) | 367.4 ± 62.7 | 422.0 ± 37.1 | −8.120 | 0.000 | 368.0 ± 65.5 | 389.2 ± 53.7 | −6.870 | 0.000 | 358.9 ± 55.7 | 359.8 ± 53.3 | −0.358 | 0.723 |

| PdetQmax (cmH2O) | 31.1 ± 8.7 | 31.5 ± 9.6 | −0.711 | 0.483 | 29.6 ± 12.1 | 30.6 ± 9.6 | −1.233 | 0.222 | 22.2 ± 8.6 | 31.1 ± 6.1 | −5.129 | 0.000 |

| PVR (ml) | 12.2 ± 8.3 | 11.7 ± 7.3 | −0.603 | 0.551 | 18.5 ± 27.0 | 18.6 ± 26.3 | −0.066 | 0.947 | 24.3 ± 24.2 | 23.6 ± 26.7 | 0.247 | 0.806 |

| Compliance | 31.8 ± 3.6 | 32.2 ± 2.8 | −1.557 | 0.130 | 27.6 ± 3.6 | 30.8 ± 2.9 | −13.146 | 0.000 | 27.5 ± 4.4 | 30.3 ± 3.6 | −4.148 | 0.000 |

R−R MS: Relapsing−remitting multiple sclerosis; P MS: Progressive multiple sclerosis; OABSS: Overactive bladder system score; Qmax: Maximum urinary flow rate; BVFD: Bladder volume at the first desire; MBV: Maximum bladder volume; PdetQmax: The detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate; PVR: Postvoid residual; MS: Multiple sclerosis; CIS: Clinically isolated syndrome.

DISCUSSION

MS is a disabling neurologic condition disease. It has protean neurologic manifestations and follows varying clinical stages. MS is characterized by focal demyelinating lesions that can occur at different levels in the central nervous system (CNS), resulting in genitourinary system dysfunction.[12] The etiology of MS is unclear, but current reports are in favor of an autoimmune origin involving CNS antigens.[13] The spinal cord controls the urine storage function, and the spinal cord and brainstem govern voiding function. For MS patients, LUTD is sustained by a complex alteration of the neurological control of the detrusor-sphincter function, resulting in detrusor over activity, detrusor hypocontractility, and/or DSD.[5] The results of the present study suggest that major patients with a diagnosis of MS present have urinary symptoms. DasGupta and Fowler reported that approximately 75% of all MS patients would develop voiding dysfunction and LUTS during the disease.[14] For MS patients, urgency and frequency were the predominantly reported irritative symptoms observed, and obstructive symptoms were hesitancy and feeling of incomplete emptying. The results were similar to the reports from Western countries, which revealed that storage symptoms such as urgency, frequency were the predominant urinary symptoms in MS.[15,16,17] Moreover, the presence of urinary symptoms was associated with more severe disability as measured with EDSS. In some studies reported, no correlation between videourodynamics finding and severity of MS was found,[18] but in others a direct link between EDSS and urologic complaints was reported.[19,20] Araki et al.[21] found that storage symptoms correlated well with EDSS but voiding symptoms did not. The variability of relationship between urinary symptoms and EDSS probably relates to the clinical type of MS, which is characterized by exacerbations and remissions.

The result of our urodynamic parameters is more solid proof of diversity of LUTD and urinary symptoms in patients with MS. The results of the present study are comparable with those of other reported series.[16,22,23] Both detrusor overactivity and DSD were the major urodynamic diagnoses in the present study. Suprasacral plaques will cause varying degrees of detrusor hyperreflexia with associated signs and symptoms, and sacral plaques will result in detrusor hypocontractility and, possibly, pudendal neuropathy. Urodynamic parameters can also objectively divide the contractility of the detrusor muscle into different levels by the pressure-flow rate diagram, allowing an intuitive and objective understanding of the detrusor function in MS patients. Urodynamic parameters examined are currently the most effective methods in identifying the type of voiding dysfunction in patients with MS. Therefore, urodynamic parameters examined should repeat at regular intervals in symptomatic patients to diagnose and optimize clinical management. Urodynamics may be helpful in providing an accurate diagnosis, guiding management decisions, and potentially, offering prognostic information on risk for upper tract deterioration. However, the universal recommendation of obtaining urodynamics in MS patients with minimal to moderate urologic symptom burden seems flawed.[24]

The treatments for MS patients include immunomodulatory therapy, hormonotherapy, behavioral therapy, and medical therapy, such as anticholinergic drugs and alpha-1 receptor blockers. Acting on the detrusor muscle, anticholinergic drugs can relieve muscle spasms, reduce bladder pressure, and relieve symptoms in the urine storage period. The alpha-1 receptor blockers not only reduce urethral resistance but also relieve voiding symptoms. Behavioral therapies include bladder training, delaying urination, and increasing the urine volume for a single time. For MS patients with urinary retention or excessive residual urine volume, the approach of intermittent catheterization was applied.

In approximately 85% of the patients who develop MS, CIS is characterized by an acute or subacute episode of neurological problems due to a single lesion within the CNS. The patient has a relatively short duration of disease, and the illness is lighter.[25] If CIS is accompanied by MRI-detectable focal white matter abnormalities at clinically unaffected sites, the chance of a second attack of demyelination, and thus of a diagnosis of clinically defined relapsing–remitting MS increases significantly.[1] For the early stage of MS patients, the improvement of the storage urine symptoms is more obvious than that in other subgroups. OABSS, bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, maximum bladder volume, and Qmax were significantly increased after the treatment. PVR, bladder compliance, and the PdetQmax were a weak change because it was normal before the treatment. Accordingly, even at early stages of the disease, i.e., in CIS patients, the presence of urinary symptoms may be used to guide treatment decisions. Because of the potential long-term predictive value of urinary symptoms, future prospective studies should be aimed at investigating the role of LUTS to predict the conversion of CISs in clinically defined MS and to predict future disability.

Relapsing–remitting MS is the predominant subtype, makes up 80% of the MS patients. It is characterized by repeated relapses and remissions as benign MS.[26] The symptoms can be acute attack or exacerbation and followed by remission with no new signs of disease activity. For relapsing–remitting MS patients, the OABSS, Qmax, and bladder volume at the first desire to voiding, bladder compliance, and maximum bladder volume were significantly increased after the treatment. However, the improvement in the PVR and the PdetQmax was not statistically significant.

Patients in progressive period are major with serious illness which is more progressive and no longer remitted, and poorly reacted for varieties of treatments. It is not obvious for the improvement of urine symptoms and maximum bladder volume and PVR. Patients in this stage are major with detrusor overactivity, detrusor hypocontractility, and DSD. The bladder volume at the first desire to voiding the PdetQmax and bladder compliance could be improved after neurology treatment. We suggest that comprehensive urodynamic parameters examined of bladder function are the keys to determine the therapy. We should give a proactive treatment to patients to relieve urinary symptoms, reduce the risk of complications, and enable these patients to cope better with their lifelong disability.

Some limitations in the present study must be pointed out. First, a weakness of the present study was that our data were collected retrospectively. Second, the number of patients enrolled was limited. Hence, we cannot make the statistical analysis between different treatment periods. In addition, many factors may lead to a system bias in the result of our urodynamic parameters. OABSS and EDSS are greatly influenced by patients’ subjective opinions. However, we believe that our results provide a useful insight for clinicians when counseling patients with MS. More high-quality trials with larger samples are proposed to learn more about the evaluation and urological management of MS. Future studies in larger cohorts of patients will aim at clarifying the specific clinical and MRI factors associated with urodynamic dysfunction in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects with MS.

In conclusion, both urinary symptoms and urodynamic dysfunctions are more prevalent in patients with MS. These results suggest that urinary symptoms are correlated significantly with MS patients’ disability status. Moreover, according to the MS’ different clinical stages, the therapeutic effect of urinary symptoms is diversified. Urodynamic parameters examined are important in evaluation and urological management of MS. Urodynamics is helpful in providing an accurate diagnosis, guiding management decisions. Early and effective treatment may improve the bladder function and the quality of life at the early stage of MS.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a grant from Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. z151100004015163).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Shao Guo

REFERENCES

- 1.Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bove R, Chitnis T. The role of gender and sex hormones in determining the onset and outcome of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:520–6. doi: 10.1177/1352458513519181. doi:10.1177/1352458513519181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilven K, Goris A. Genetic burden mirrors epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1353–4. doi: 10.1177/1352458515596603. doi:10.1177/1352458515596603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiedemann A, Kaeder M, Greulich W, Lax H, Priebel J, Kirschner-Hermanns R, et al. Which clinical risk factors determine a pathological urodynamic evaluation in patients with multiple sclerosis?An analysis of 100 prospective cases. World J Urol. 2013;31:229–33. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0820-y. doi:10.1007/s00345-011-0820-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah P. Symptomatic management in multiple sclerosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18(Suppl 1):S35–42. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.164827. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.164827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemack GE, Hawker K, Frohman E. Incidence of upper tract abnormalities in patients with neurovesical dysfunction secondary to multiple sclerosis: Analysis of risk factors at initial urologic evaluation. Urology. 2005;65:854–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.11.038. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caramella D, Donatelli G, Armillotta N, Manassero F, Traversi C, Frumento P, et al. Videourodynamics in patients with neurogenic bladder due to multiple sclerosis: Our experience. Radiol Med. 2011;116:432–43. doi: 10.1007/s11547-011-0620-2. doi:10.1007/s11547-011-0620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. doi:10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurtzke JF. Historical and clinical perspectives of the expanded disability status scale. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000136645. doi:10.1159/000136645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schäfer W, Abrams P, Liao L, Mattiasson A, Pesce F, Spangberg A, et al. Good urodynamic practices: Uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:261–74. doi: 10.1002/nau.10066. doi:10.1002/nau.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. doi:10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciancio SJ, Mutchnik SE, Rivera VM, Boone TB. Urodynamic pattern changes in multiple sclerosis. Urology. 2001;57:239–45. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01070-0. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(00)01070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartung HP, Archelos JJ, Zielasek J, Gold R, Koltzenburg M, Reiners KH, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules and inflammatory mediators in demyelination: A review. Neurology. 1995;45(6 Suppl 6):S22–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6_suppl_6.s22. doi:10.1212/WNL.45.6 Suppl 6.S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DasGupta R, Fowler CJ. Sexual and urological dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: Better understanding and improved therapies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:271–8. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200206000-00008. doi:10.1097/00019052-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Popolo G, Panariello G, Del Corso F, De Scisciolo G, Lombardi G. Diagnosis and therapy for neurogenic bladder dysfunctions in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurol Sci. 2001;29(Suppl 4):S352–5. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-1042-y. doi:10.1007/s10072-008-1042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tadayyon F, Etemadifar M, Bzeih H, Zargham M, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Akbari M, et al. Association of urodynamic findings in new onset multiple sclerosis with subsequent occurrence of urinary symptoms and acute episode of disease in females. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:382–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engeler DS, Meyer D, Abt D, Müller S, Schmid HP. Sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction caused by multiple sclerosis: A single-centre prospective series. BMC Urol. 2015;15:105. doi: 10.1186/s12894-015-0102-x. doi:10.1186/s12894-015-0102-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbalias GA, Liatsikos EN, Passakos C, Barbalias D, Sakelaropoulos G. Vesicourethral dysfunction associated with multiple sclerosis: Correlations among response, most prevailing clinical status and grade of the disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;32:349–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1017597016622. doi:10.1023/A: 1017597016622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Almeida CR, Carneiro K, Fiorelli R, Orsini M, Alvarenga RM. Urinary dysfunction in women with multiple sclerosis: Analysis of 61 patients from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Neurol Int. 2013;5:e23. doi: 10.4081/ni.2013.e23. doi:10.4081/ni.2013.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onal B, Siva A, Buldu I, Demirkesen O, Cetinel B. Voiding dysfunction due to multiple sclerosis: A large scale retrospective analysis. Int Braz J Urol. 2009;35:326–33. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382009000300009. doi:10.1590/S1677-55382009000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araki I, Matsui M, Ozawa K, Takeda M, Kuno S. Relationship of bladder dysfunction to lesion site in multiple sclerosis. J Urol. 2003;169:1384–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000049644.27713.c8. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000049644.27713.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemack GE, Frohman EM, Zimmern PE, Hawker K, Ramnarayan P. Urodynamic distinctions between idiopathic detrusor overactivity and detrusor overactivity secondary to multiple sclerosis. Urology. 2006;67:960–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.061. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Çetinel B, Tarcan T, Demirkesen O, Özyurt C, Sen I, Erdogan S, et al. Management of lower urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and Turkish consensus report. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:1047–57. doi: 10.1002/nau.22374. doi:10.1002/nau.22374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dillon BE, Lemack GE. Urodynamics in the evaluation of the patient with multiple sclerosis: When are they helpful and how do we use them? Urol Clin North Am. 2014;41:439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2014.04.004. ix. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller DH, Chard DT, Ciccarelli O. Clinically isolated syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:157–69. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70274-5. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jongen PJ, Wesnes K, van Geel B, Pop P, Schrijver H, Visser LH, et al. Does self-efficacy affect cognitive performance in persons with clinically isolated syndrome and early relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler Int 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/960282. 960282. doi:10.1155/2015/960282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]