Uveal melanoma is the most common primary ocular malignancy in adults, with an annual incidence of 6–7 cases/million people.[1,2,3] The choroid is the most common site of involvement occurring in more than 90% patients.[3] We conducted a retrospective study for uveal melanoma at Tongren Eye Center from 1997 to 2011. A total of 682 cases of uveal melanoma were recorded. Among them, 176 (25.8%) cases received local resection surgery. Most of them survived after surgery and had good recovery. However, life-threatening complication of acute pulmonary embolism (APE) occurred in 3 choroidal melanoma patients shortly after surgery. Till now, to the best of our knowledge, there are few reports of severe postsurgical complications of choroidal melanoma.

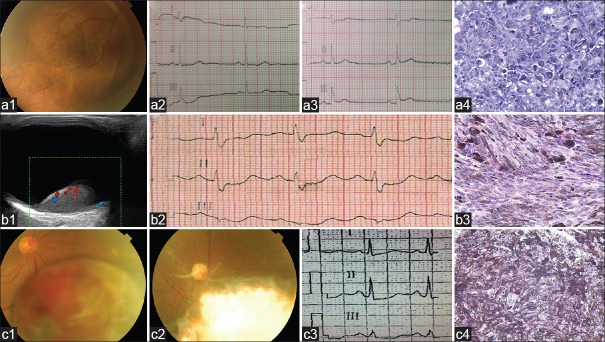

A 41-year-old woman complained of decreasing visual acuity in her right eye (case 1). The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 1.3 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) in the right eye. A large brown choroidal mass arose from the inferotemporal quadrant of the right fundus [Figure 1, a1]. On ultrasonography, the mass showed relatively medium internal reflectivity with rich blood flow signal in it. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) revealed mottled hyperfluorescent areas and many leakage points in the mass in the early phase followed by its marked staining in the later phase. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hyperintense on T1-weighted images with markedly enhancement and hypointense on T2-weighted images. The provisional diagnosis was choroidal melanoma. We performed vitrectomy and lensectomy under general anesthesia with controlled hypotension. The blood pressure (BP) was controlled to be about 75/40 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa) intraoperatively. The tumor was completely excised with silicone oil tamponade. The pathological diagnosis was choroidal melanoma [Figure 1, a4].

Figure 1.

Preoperative examinations and postoperative pathologic examinations of the three patients. (a) Case 1. (a1) Fundus photograph: A large brown choroidal mass arose from the inferotemporal quadrant of the right fundus with an adjacent retinal detachment; (a2 and a3) Comparing the two ECG results, there appear the changes of SIQIII; (a4) immunohistochemical stain, the tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein (original magnification, ×200). (b) Case 2. (b1) Color Doppler ultrasound image of the tumor: Tumor is globular, with a mild–moderate echo, blood flow can be detected in tumor, choroidal excavation is present; (b2) ECG revealed sinus rhythm and SIQIIITIII; (b3) Immunohistochemical stain, the tumor cells were positive for melanin-A and were in brown color (original magnification, ×200). (c) Case 3. (c1) Fundus photograph: A large brown choroidal mass arose from the inferonasal quadrant of the right fundus with some bleeding and exudation on its surface accompanied by an adjacent retinal detachment; (c2) Fundus photograph of the right eye 3 years after tumor resection: Choroidal defect with shallow retinal detachment, there is no sign of tumor recurrence; (c3) ECG showed sinus tachycardia and SITIII; (c4) Immunohistochemical stain, the tumor cells were strongly positive for human melanoma black-45 and were in brown color (original magnification, ×200). ECG: Electrocardiogram.

Five hours after surgery, the patient suddenly developed cyanosis, dyspnea, and lost consciousness, electrocardiogram (ECG) examination showed SIQIII [Figure 1, a2, a3] and incomplete right bundle branch block. The blood gas analysis showed that CO2 partial pressure (PaCO2) was 63.7 mmHg, O2 partial pressure (PaO2) was 28 mmHg, O2 saturation (SaO2) was 24.4%, and D-Dimmer was 436 μg/L. The provisional diagnosis was APE. The patient rapidly died. The confirmation of the diagnosis required autopsy; however, the family of the deceased refused to do so.

A 38-year-old man was referred to our eye center for an intraocular mass in his left eye (case 2). The left BCVA was 1.7 logMAR. A large brown choroidal mass arose from the inferonasal quadrant of the left fundus. Ocular ultrasonography [Figure 1, b1], FFA, ICGA, and MRI examinations implied that the tumor was choroidal melanoma. The tumor was locally resected under general anesthesia with controlled hypotension. Lower extremity cuff was used during surgery to prevent deep vein thrombosis. The BP was controlled to be about 90/50 mmHg intraoperatively. The tumor was completely excised with silicone oil tamponade. The pathological diagnosis was choroidal melanoma [Figure 1, b3].

Three hours postoperatively, the patient suddenly appeared gasping, chest tightness, and chest pain. His lips and nails appeared cyanosis and the BP was 90/60 mmHg. ECG revealed sinus rhythm and SIQIIITIII [Figure 1, b2]. The blood gas analysis showed that PaCO2 was 56.4 mmHg, PaO2 was 42.6 mmHg, and SaO2 was 60.4%. The diagnosis was provisional APE. Finally, he died at 5 h postoperatively.

A 47-year-old man was referred to our eye center for an intraocular mass lesion in his right eye (case 3). The right BCVA was 0.3 logMAR. A large brown choroidal mass arose from the inferonasal quadrant of the right fundus [Figure 1, c1]. Ocular examinations implied that the tumor was choroidal melanoma. We performed local resection under local anesthesia with monitored anesthesia care. The intraoperative BP was 112/70 mmHg. The tumor was completely excised with silicone oil tamponade. The pathological diagnosis was choroidal melanoma [Figure 1, c4].

Twelve hours postoperatively, the patient complained of continuing xiphoid discomfortness, chest tightness, and gasp. The BP was 90/60 mmHg and the pulse was 120/min. ECG showed sinus tachycardia, lung-shaped P wave, mild change in ST-T and SITIII [Figure 1, c3]. The blood gas analysis showed that PaO2 was 31.5 mmHg, PaCO2 was 37 mmHg, and SaO2 was 54%. Ultrasonic cardiogram showed right ventricular enlargement. Chest X-ray showed pleural effusion. The diagnosis was APE. The patient was given thoracentesis, low molecular weight heparin, and warfarin for anticoagulant therapy. The symptoms were significantly relieved. The BP was 100/60 mmHg, pulse was 72/min, and the ultrasonic cardiography was normal. Till now (5 years postoperatively), the patient has no signs of tumor recurrence [Figure 1, c4] and metastasis.

Till now, to the best of our knowledge, there are few reports of patients who died soon after local resection surgery of uveal melanoma due to surgery complications. All the above three cases were considered to develop APE shortly after surgery.

The emboli of these three cases may be derived from lower extremity venous thrombus. Other sources include tumor tissue and silicone oil droplets. However, the pathogenesis is most likely to be thrombosis. Hypotensive anesthesia can reduce surgical bleeding, but it can also be a predisposing factor of thrombosis.[4] The first two patients, who died, had gotten general anesthesia with controlled hypotension. The intraoperative BP was reduced to 75/40 mmHg or 90/50 mmHg. The third patient was given local anesthesia, and the BP was maintained normal during surgery. For the second patient, we have taken adequate precautions, including preoperative lower extremity ultrasound examination, maintaining blood volume, and using lower extremity cuff intraoperatively. But, still he died. For the third patient, we chose to use local anesthesia instead of general anesthesia with controlled hypotension, and eventually, he survived.

There are two main causes for thrombosis: (1) surgery itself as a trauma can stimulate the body's stress response and lead the unbalance of in vivo coagulation, anticoagulation, and thrombolytic system. (2) Under controlled hypotension during surgery, the blood flows more slowly, and the risk of thrombosis is higher. We speculate that thrombus of the first two patients are larger than the third one because of the hypotension during surgery. Hence, the first two patients’ conditions were more serious and critical, and they died eventually.[4,5]

The pathogenesis of these three patients is APE due to thrombosis. Surgery and controlled hypotension are the predisposing factors for thrombosis. From the clinical courses of these patients, we should be cautious on controlling hypotension and APE.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Qiang Shi

REFERENCES

- 1.Egan KM, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, Gragoudas ES, Albert DM. Epidemiologic aspects of uveal melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:239–51. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90173-7. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(88)90173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zehetmayer M, Kitz K, Menapace R, Ertl A, Heinzl H, Ruhswurm I, et al. Local tumor control and morbidity after one to three fractions of stereotactic external beam irradiation for uveal melanoma. Radiother Oncol. 2000;55:135–44. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00164-x. doi:10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toktas ZO, Bicer A, Demirci G, Pazarli H, Abacioglu U, Peker S, et al. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery yields good long-term outcomes for low-volume uveal melanomas without intraocular complications. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:441–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman JR, Pensak MJ. Prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1801–11. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01328. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredin H, Gustafson C, Rosberg B. Hypotensive anesthesia, thromboprophylaxis and postoperative thromboembolism in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1984;28:503–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1984.tb02107.x. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1984.tb02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]