Abstract

Background

It is well known that liver and lung injury can occur simultaneously during severe inflammation (e.g. multiple organ failure). However, whether these are parallel or interdependent (i.e. liver:lung axis) mechanisms is unclear. Previous studies have shown that chronic ethanol consumption greatly increases mortality in the setting of sepsis-induced acute lung injury (ALI). The potential contribution of subclinical liver disease in driving this effect of Ethanol on the lung remains unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to characterize the impact of chronic Ethanol exposure on concomitant liver and lung injury.

Methods

Male mice were exposed to ethanol-containing Lieber-DeCarli diet or pair-fed control diet for 6 weeks. Some animals were administered lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 4 or 24 hours prior to sacrifice to mimic sepsis-induced ALI. Some animals received the TNFα blocking drug, etanercept, for the duration of alcohol exposure. The expression of cytokine mRNA in lung and liver tissue was determined by qPCR. Cytokine levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and plasma were determined by Luminex assay.

Results

As expected, the combination of Ethanol and LPS caused liver injury, as indicated by significantly increased levels of the transaminases ALT/AST in the plasma and by changes in liver histology. In the lung, Ethanol preexposure enhanced pulmonary inflammation and alveolar hemorrhage caused by LPS. These changes corresponded with unique alterations in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the liver (i.e TNFα) and lung (i.e. MIP-2, KC). Systemic depletion of TNFα (etanercept) blunted injury and the increase in MIP-2 and KC caused by the combination of ethanol and LPS in the lung.

Conclusions

Chronic Ethanol preexposure enhanced both liver and lung injury caused by LPS. Enhanced organ injury corresponded with unique changes in the pro-inflammatory cytokine expression profiles in the liver and the lung.

Keywords: Alcohol, Alcoholic liver disease, Acute lung injury, Inflammation

Alcohol use is widespread in the United States with more than half of Americans reporting alcohol consumption on a weekly basis (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2010). It has long been known that chronic alcohol consumption can lead to the development of a myriad of health effects spanning a variety of organs including the brain, gut, liver and lungs. Indeed, the effects associated with chronic alcohol consumption have made alcohol the third leading risk factor globally for disease and disability (World Health Organization 2011) at a cost of more than $166 billion annually to treat the medical consequences of alcohol abuse (Nelson and Kolls 2002). Despite the known health risks, alcohol consumption remains pervasive in today’s culture. In toto, alcohol consumption is responsible for ~6% of all disability-adjusted life years (DALY) lost in the United States (US Burden of Disease Collaborators 2013), most of which are attributable to alcohol-induced toxicity.

The liver is well recognized as a major target of alcohol-induced organ injury. This is due in part to the high concentrations of alcohol reached in the portal blood as well as the detrimental effects of ethanol metabolism (e.g., oxidative stress). Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is actually a spectrum of disease states that include simple steatosis (fat accumulation), steatohepatitis, and in more severe cases fibrosis and cirrhosis. A major focus in ALD therapy is to treat the decompensation associated with end-stage ALD (i.e., cirrhosis); indeed, the sequelae of a failing liver (e.g., ascites, portal hypertension, and hepatorenal syndrome) are generally what causes death in end-stage ALD. Although the successful treatment of these secondary effects prolongs the life of ALD patients, this therapy is only palliative; there are currently no therapies to halt or prevent the progression of ALD.

Alcohol consumption can also contribute to lung damage. In contrast to the liver, alcohol consumption does not appear to directly cause any overt pulmonary pathology; however, alcohol is known to exacerbate the severity of lung damage from other causes. It has been estimated that up to 190,000 people suffer from acute lung injury (ALI) annually in the United States (Rubenfeld et al. 2005). The risk of developing more severe forms of ALI such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is significantly higher in people who meet the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders (Moss et al. 1996). Whereas alcohol consumption does not cause overt pathology in the lung, studies have shown that experimental alcohol exposure can lead to subtle changes to this organ, which has been coined the ‘alcoholic lung phenotype.’ This effect of alcohol is characterized by dysregulated inflammatory response (Bechara et al. 2003), and tissue remodeling (Burnham et al. 2007). The dysregulated inflammatory response caused by alcohol in the lung is dependent on both the amount and duration of alcohol consumption and is suspected to be a key player in alcohol-related lung dysfunction (D’Souza et al. 1992). The exact mechanisms that mediate the development of the alcoholic lung phenotype and increased risk of ALI/ARDS remain unclear. Better understanding of this complex process could identify potential therapeutic targets to treat or prevent alcohol-related lung dysfunction, such as ALI/ARDS.

It is now clear that many human diseases develop through a multi-stage, multi-hit process; it is therefore not surprising that multiple cells within a target organ contribute to disease pathology. Indeed, system level analyses of disease, and organ-organ interactions, are gaining the attention of the research community. Several studies indicate a potential interdependence between liver and lung in organ pathology. For example, mortality in ALI in the setting of severe hepatic disease is almost 100% (Khanlou et al. 1999). In experimental models of liver injury, vascular permeability and leukocyte activation in lungs are increased (Matuschak 1996). Studies investigating the multi-organ effects of endotoxemia indicate that interaction between the liver and lung are not only likely, but may occur via alcohol-induced mediators, including TNFα (Matuschak et al. 1994), an inflammatory cytokine markedly increased in ALD (McClain and Cohen 1989).

The purpose of this study was to characterize a model of concomitant liver and lung injury in the setting of chronic alcohol exposure. It was hypothesized that chronic alcohol exposure acts as a first ‘hit’ that sensitizes these organs to a second inflammatory stimulus (e.g., bacterial lipopolysaccharide; LPS). The parallel mechanisms of liver and lung injury in this ‘2-hit’ model were explored. Furthermore, the potential interdependence of liver and lung injury via systemic release of TNFα was also determined.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment

Mice were housed in a pathogen-free barrier facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and procedures were approved by the University of Louisville’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight-week old male C57BL6/J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and exposed to either ethanol-containing or control Lieber DeCarli diet (Dyets Inc) for six weeks (Figure 1A). Briefly, ethanol-fed mice were given diet that contained increasing concentrations of ethanol over a period of three weeks until a concentration of 6% (vol/vol) ethanol was reached; ethanol-fed mice were then maintained on the 6% ethanol diet for the remaining 3 weeks of the study. Control animals were pair-fed an isocaloric control diet. At the end of the exposure period, the animals were separated into 2 additional groups to receive either LPS (E. coli, serotype 055:B5; Sigma, St Louis, MO; 10 mg/kg i.p.) or vehicle (saline) and euthanized 4 or 24 h after injection; these timepoints were selected from preliminary studies to characterize the peak of cytokine production (4 h) and pathology (24 h) in this model. During the course of the study, some animals were administered the TNFα blocking drug etanercept (Wyeth; 10 mg/kg in PBS) by i.p. injection two times per week during ethanol administration, as described by others (Budinger et al. 2011; Karabela et al. 2011). Control animals received PBS vehicle, (1 μl/g; i.p) twice per week.

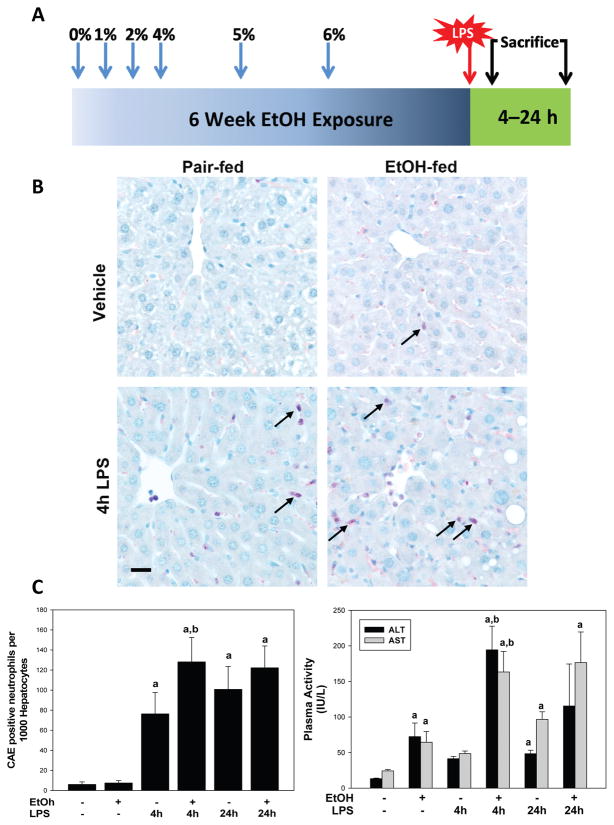

Figure 1. Effects of chronic ethanol preexposure on LPS induced hepatic injury.

Panel A: Animals and treatments are as described in Materials and Methods. Panel B: Representative photomicrographs (400×) of liver tissue after Chloroacetate-esterase (CAE) staining are shown for both the four and 24 h timepoint. Neutrophils (arrows) are stained pink. Panel C: Plasma ALT and AST (left) and quantitative analysis of CAE histochemistry (right) are shown. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6–8); a, p < 0.05 compared to pair fed controls; b, p < 0.05 compared to LPS alone. Calibration bar = 20 μm.

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100/15 mg/kg, i.m.) at time of sacrifice. Blood was collected from the vena cava just prior to sacrifice by exsanguination and citrated plasma was stored for further analysis. Lungs were flushed prior to lavage to remove erythrocytes. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed by flushing the lung two times with 400 μL sterile PBS. Cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were counted before being separated by centrifugation, removed from remaining BALF, and fixed on slides for further analysis (Lyer et al. 2009). Portions of liver tissue and lung tissue were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for later analysis or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for subsequent sectioning and mounting on microscope slides. A portion of liver tissue was frozen-fixed in OCT-Compound (Satura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Total RNA was immediately extracted from fresh liver and lung tissue using RNA-stat (Tel-Test, Austin, TX) and chloroform:phenol separation.

Histology and Clinical Chemistry

Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined spectrophotometrically using standard kits (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA). Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections were cut at 5 μm and mounted on glass slides. Sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Chloroacetate esterase (CAE) staining for neutrophils was performed using the naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on paraffin embedded samples (Beier et al. 2009). CAE-positive cells were characterized by light pink (i.e. CAE-positive) cytosolic staining and bi-lobed nuclear morphology. For liver tissue, the extent of CAE staining was quantified by counting the number of CAE-positive neutrophils per 1000 hepatocytes (Beier et al. 2009). For lung tissue, total CAE-positive cells were counted per 10 fields. During quantification, neutrophils were characterized by light pink (i.e. CAE-positive) staining and bi-lobed nuclear morphology. Myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) was measured as previously described (von Montfort et al. 2008), and were normalized to lung tissue wet weight. For scoring septal thickness, 20 H+E photomicrographs (400×) per sample were captured; 4 randomly selected alveolar septa on each picture were measured using a digital caliper function (Metamorph, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA). Areas in which the septa may be artificially (e.g., underinflated region) or naturally (e.g., directly adjacent to a blood vessel) thickened were avoided. Summary data were reported as fold of control.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The mRNA expression of select genes was detected by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), which is routine for this group (Beier et al. 2009). PCR primers and probes for TNFα, PAI-1, IL-6, IL-10 and β-actin were designed using Primer 3 (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, MA). Primers and probes for MIP-2, and KC were bought from Applied Biosystems as kits (Foster City, CA). All primers were designed to cross introns to ensure that only cDNA and not genomic DNA was amplified. Amplification reactions were carried out using the ABI StepOne Plus machine and software (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). The comparative CT method was used to determine fold changes in mRNA expression compared to an endogenous reference gene (β-actin). This method determines the amount of target gene, normalized to an endogenous reference and relative to a calibrator (2−ΔΔCt).

Luminex

Cytokine levels in plasma and BALF samples were measured using the MILLIPLEX MAP Magnetic Bead Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Panel (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The plate was read using a Luminex 100 plate reader and Exponent software. MILLIPLEX MAP assay was performed according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Plasma (4x dilution) or BALF samples (undiluted) were added to a clear bottomed black 96 well plate. Antibody-immobilized beads were added to samples and the plate was incubated overnight at 4°C on a plate shaker at 600 rpm. Detection antibody was added to wells and incubated for 1 hour followed by the addition of strepavidin-phycoerythrin. Quantitative analysis of the assay was performed using the Luminex 100™ IS. Data capture and analysis were performed using the Luminex Xponent software.

Statistical Analyses

Results are reported as means ± standard error mean (SEM; n = 6–10). 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc test (for parametric data) or Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test (for nonparametric data) was used for the determination of statistical significance among treatment groups, as appropriate. A p value less than 0.05 was selected before the study as the level of significance.

Results

Throughout the duration of dietary exposure, all mice gained ~0.6 g/week, with no differences between dietary and treatment groups. In saline-treated mice fed control diet, liver weights (as percent of body weight) were 4.7 ± 0.1 g, whereas ethanol-fed mice had liver weights of 4.8 ± 0.2 g. Liver weights in both groups were unchanged by LPS exposure.

Ethanol feeding enhanced LPS-induced liver injury

6 weeks exposure to ethanol-containing diet caused mild liver damage, characterized predominantly by microvesicular fat accumulation in midzonal regions of the liver. LPS administration to pair-fed animals increased the accumulation of inflammatory foci in liver. As expected, feeding ethanol-containing diet increased the severity and frequency of necroinflammatory foci caused by LPS administration. Figure 1B shows staining for neutrophils using chloroacetate esterase staining (CAE staining). Chronic ethanol exposure did not significantly affect neutrophil infiltration compared to their pair-fed counterparts in the absence of LPS (Figures 1C); ethanol pre-exposure significantly enhanced neutrophil infiltration caused by LPS 4 hr after administration (Figure 1C).

Plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined as indices of liver injury (Figure 1C). Chronic ethanol exposure significantly increased ALT and AST levels in the plasma. LPS alone tended to increase these variable at the 4 h timepoint, but did not significantly affect circulating levels of ALT or AST until 24 h after injection. The combination of ethanol exposure and LPS significantly increased plasma ALT and AST 4 h after LPS administration, with values ~4-fold higher than with LPS alone. There were no significant differences in transaminases between the pair-fed and ethanol fed animals 24 h after LPS injection (1C).

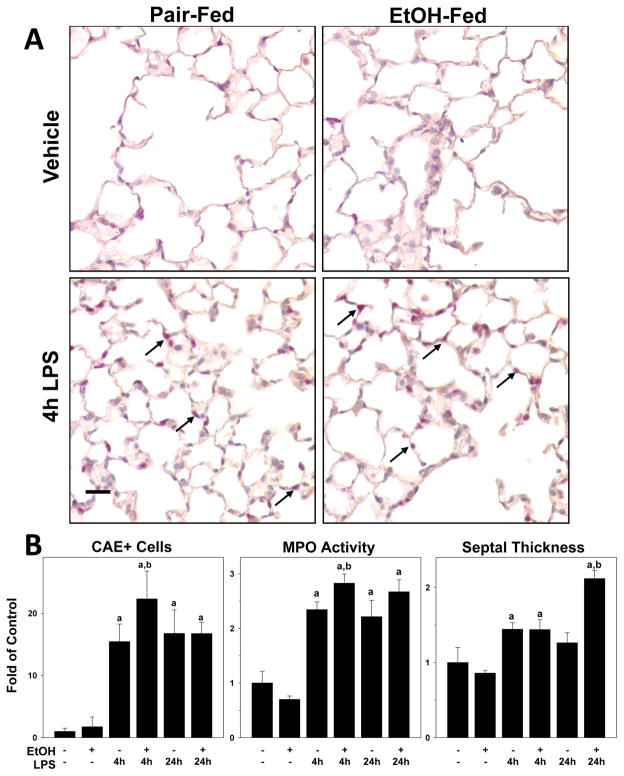

Ethanol enhanced LPS-induced lung injury and inflammation

In liver, LPS injection caused noticeable pathologic changes as early as 4 h after administration (Figure 1). In contrast, early changes in pulmonary pathology in the lung tissue was relegated to inflammation (Figure 2). Basal neutrophil counts in naïve mice was 1.0±0.2 PMN/field. As expected (Reutershan and Ley 2004), LPS exposure significantly increased the level of neutrophils in the lung, with values of at the 4 h timepoint. Ethanol exposure alone did not affect neutrophil levels in the lung in the absence of LPS, but significantly enhanced the effect of LPS by ~50% (Figure 2B). Neutrophil infiltration remained elevated 24 h after LPS exposure, but was no longer significantly different between ethanol-fed and pair-fed groups at this timepoint. Hepatic inflammation is generally homogenous across the organ. In contrast, lung inflammation is characterized by ‘hot spots,’ which may make it difficult to accurately assess organ level inflammation in the lungs by histology alone. Therefore, pulmonary neutrophil accumulation was also documented by lung myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (Figure 2B). The pattern of effect of LPS and ethanol on pulmonary MPO activity was similar to that observed for CAE staining (Figure 2B), and ethanol significantly enhanced the increase in MPO activity caused by LPS 4 h after injection..

Figure 2. Effects of chronic ethanol preexposure on LPS induced lung injury and inflammation.

Panel A: Representative photomicrographs (400×) of lung tissue after CAE staining are shown. LPS exposure caused inflammatory injury in the lung, as evidenced by inflammatory cells in the pulmonary interstitium (arrows). Panel B: Quantitative analysis of CAE histochemistry (left), myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (middle) and septal thickness (right) are shown. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6–8); a, p < 0.05 compared to pair fed controls; b, p < 0.05 compared to LPS alone. Calibration bar = 20 μm.

Analogous to findings in liver, ethanol enhanced LPS-induced lung damage, which was characterized by an increase in the frequency and severity of alveolar hemorrhage caused by LPS. At the 24 h timepoint, LPS caused areas of alveolar hemorrhage in the lung, as indicated by an increase in the number of red blood cells in the pulmonary interstitium. Hemorrhage was macro-heterogeneous, with some areas exhibiting a higher degree of hemorrhaging than others. The increase in alveolar wall (septal) thickness caused by LPS was also more pronounced after ethanol exposure 24 h after LPS administration (Figure 2B).

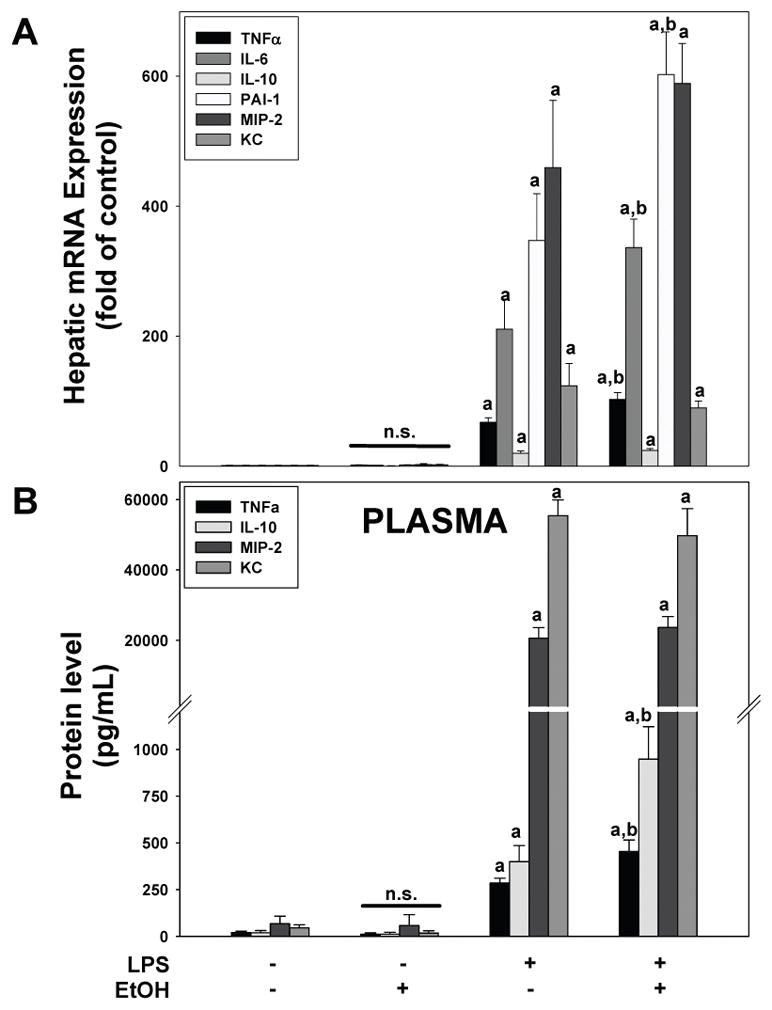

Ethanol differentially alters cytokine/chemokine expression in the liver and lung

The assessment of liver (Figure 1) and lung (Figure 2) injury indicates that chronic ethanol exposure enhanced the inflammation and damage caused by LPS in both organs. To further characterize the mechanisms by which ethanol causes these effects, the mRNA expression of key inflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and PAI-1) were determined by qPCR (Figures 3A and 4A). Chronic alcohol exposure alone caused no significant changes in mRNA expression of these select cytokines in either the liver or lung in the absence of LPS (Figures 3A and 4A). LPS administration alone significantly increased hepatic mRNA expression of TNFα, IL-6, IL-10 and PAI-1 (Figure 3A). Additionally LPS administration increased the expression of the chemokines MIP-2 and KC. As expected from previous studies, chronic ethanol exposure enhanced the increase in TNFα, IL-6 and PAI-1 mRNA expression levels seen with LPS alone in the liver, but did not significantly enhance the expression of MIP-2 and KC.

Figure 3. Effect of ethanol preexposure causes unique changes in the expression of soluble mediators in the liver and and plasma.

Real time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression (Panel A) and Luminex multiplex assay of plasma proteins (Panel B) are shown. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6–8); a, p < 0.05 compared to pair fed controls; b, p < 0.05 compared to LPS alone.

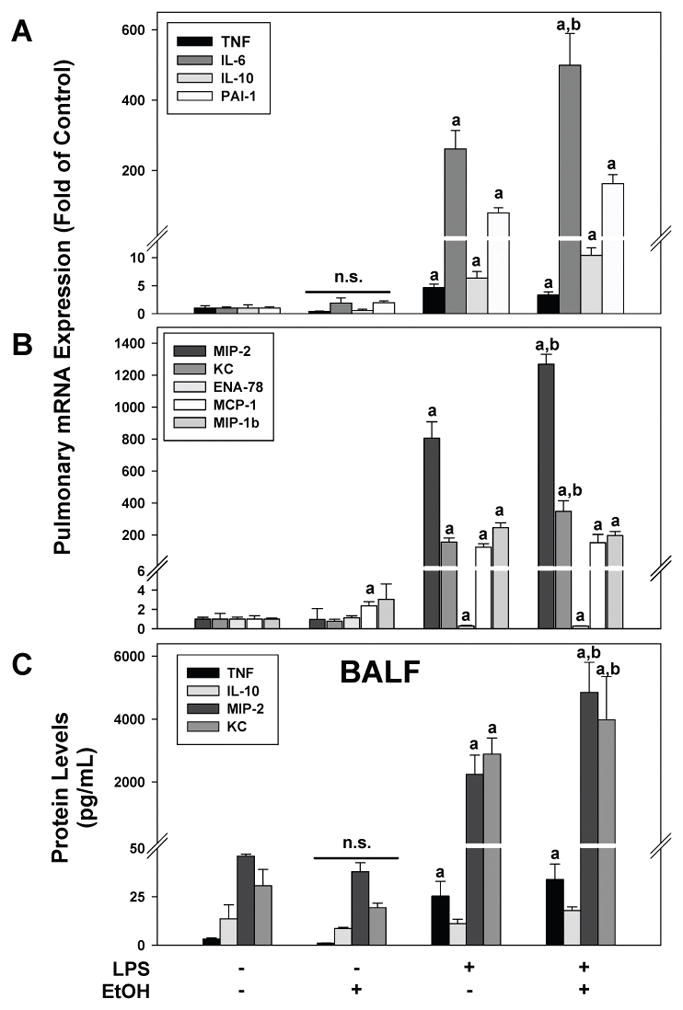

Figure 4. Ethanol preexposure causes unique changes in the expression of soluble mediators in the lung.

Real time RT-PCR of pulmonary expression (Panels A and B) and Luminex multiplex assay of BALF (Panel C) are shown. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6–8); a, p < 0.05 compared to pair fed controls; b, p < 0.05 compared to LPS alone.

Similar to the results seen in the liver, LPS administration alone increased the pulmonary mRNA expression of all mediators (Figure 4A); however, the increase in TNFα was much less pronounced compared to liver and MIP-2 was the inflammatory mediator that was most robustly altered. In contrast to the liver, chronic ethanol exposure did not significantly enhance the increase in TNFα expression seen with LPS alone. However, ethanol did enhance the increases in IL-6 caused by LPS in the lung (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the induction in the expression of the chemokines MIP-2 and KC caused by LPS were significantly enhanced by ethanol diet (Figure 4B). The expression of other chemokines (Figure 4B) associated with experimental ALI (i.e., ENA-78, MCP-1 MIP-1b) were either not induced by LPS (ENA-78) or the induction caused by LPS was not enhanced by ethanol administration (MCP-1 and MIP-1b). Interestingly, the expression of MCP-1 was increased by ethanol administration alone in the lung (Figure 4B). These mRNA expression patterns for ethanol +/− LPS was similar at the 24 hr timepoint, albeit less pronounced (data not shown). Previous studies have shown that LPS and ethanol alter the expression of the LPS receptor complex TLR4 and CD14. Neither LPS nor ethanol changed the expression of TLR4 in the lung (not shown). LPS administration increased the expression of CD14 in the lung, which peaked 4 h after injection (18±1 fold over control); ethanol did not significantly alter the increase in expression of CD14 caused by LPS (24±3 fold over control).

Although it is not the sole source, it is known that the liver is a major contributor to the increase in inflammatory mediators in plasma in response to i.p. LPS administration (Bautista et al. 1994). Likewise, BALF accumulates inflammatory mediators produced by lung tissue. The presence of select mediators (TNFα, IL-10, MIP-2 and KC) in the plasma (Figure 3B) and BALF (Figure 4C) were therefore determined via Luminex assay. With the exception of IL-10 in the BALF (Figure 4C), LPS treatment alone increased the levels of all four inflammatory mediators in the plasma and BALF. Chronic ethanol exposure did not increase the levels any mediator in either plasma or BALF; however, ethanol diet enhanced the increase in plasma TNFα and IL-10 (but not MIP-2 and KC) caused by LPS (Figure 4B). In contrast, ethanol diet enhanced the increase in MIP-2 and KC (but not TNFα and IL-10) levels caused by LPS in the BALF (Figure 4C).

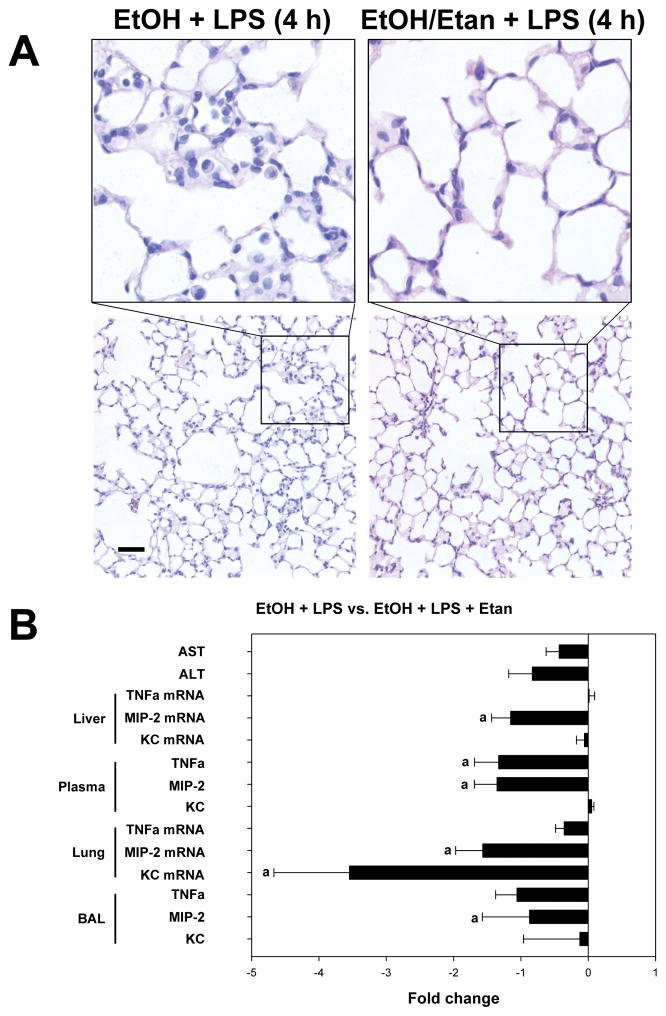

Effect of etanercept on indices of injury and inflammation

Previous studies have established that TNFα production is critical for subsequent pulmonary chemokine (e.g., MIP-2 and KC) production and injury in experimental models of ALI (Calkins et al. 2001). It is unclear, however, whether the source of TNFα needs to be pulmonary vs. systemic in order to see this effect in the lungs. Therefore, etanercept was used to deplete systemic TNFα. The effects of etanercept on indices of damage and inflammation in the liver and lung were then measured. Etanercept blunted the enhanced lung injury caused by the combination of ethanol and LPS and decreased the recruitment of infiltrating cells (Figure 5A). Co-administration of etanercept during the course of the study partially protected against liver injury, as determined by AST levels (Figure 5B), but did not affect steatosis or inflammation caused by ethanol or LPS (data not shown). Etanercept administration decreased levels of freely soluble TNFα in response to the combination of LPS in the plasma and BALF, by 1.3-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively (Figure 5B). Interestingly, etanercept administration caused a 1.3-fold decrease in plasma MIP-2 levels which correlated with a decrease in MIP-2 mRNA expression in the liver. Etanercept also caused a decrease in MIP-2 in the BALF as well as a 3.2-fold decrease in KC levels in the BALF. The decrease in BALF KC levels correlated with a 3.5-fold decrease in pulmonary KC mRNA expression (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Etanercept protects against inflammatory damage in the lung.

Panel A shows representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained lung tissue at 1200× magnification (top) and 200× magnification (bottom) from animals exposed to the combination of ethanol and 4 h LPS in the absence (left) or presence (right) of the TNFα binding drug etanercept. Panel B shows the fold change in indices of liver injury (ALTand AST), mRNA expression of TNFα, MIP-2 and KC, and protein levels of these mediators in the plasma and BALF. Quantitative data are shown as fold change in animals exposed to LPS and ethanol in the presence of etanercept compared to animals that were exposed to LPS and ethanol in the absence of etanercept. Quantitative data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 6–8); a, p < 0.05 compared to pair fed controls; b, p < 0.05 compared to LPS alone. Calibration bar = 40 μm.

Discussion

It is now generally accepted that human disease can be a multi-stage, multi-hit process in which various cells within a target organ contribute to disease pathology. In addition to cell-cell interactions within a single organ, recent studies have begun to highlight the importance of more complex interactions, including those between multiple organs. One example of such inter-organ interaction in the setting of alcohol exposure is the critical link between the intestine and the liver, or the gut-liver axis (Szabo and Bala 2010). Indeed, a myriad of experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated that alcohol-induced gut dysbiosis and subsequent impairment of the gut barrier results in the release of gut-derived toxins (e.g. LPS) and endotoxemia (Hartmann et al. 2012). Today, the gut-liver axis and enteric dysbiosis is a widely-accepted component in the development of ALD as well as other liver diseases (Szabo & Bala 2010).

This group is particularly interested in potential interactions between the liver and lung, i.e. the liver-lung axis, in the context of alcohol exposure. As mentioned in the introduction, liver disease is associated with increased incidence of acute lung injury and enhanced mortality. These and other findings have suggested a potential interaction between the liver and lung that may represent an important aspect of the pathophysiology of acute lung injury, particularly in the setting of sepsis. Siore and collaborators tested the possible interaction between the liver and lung in a study performed in an in situ perfused piglet preparation (Siore et al. 2005). Their model revealed that hypoxemia and pulmonary edema were only observed when the liver and lung circulations were connected. Their results indicate that while endotoxemia could directly cause pulmonary vasoconstriction and leukocyte sequestration, interaction between the liver and lung was required for severe inflammatory response and oxidative injury to the lung. Additional studies have also shown that pulmonary injury induced by systemic endotoxin can be altered by mediators released from the liver (e.g. TNFα) (Matuschak 1996; Siore et al. 2005). Unfortunately, few studies have investigated the potential interactions between the liver and lung in the setting of chronic alcohol exposure. Therefore the goal of this study was to characterize a model of concomitant liver and lung injury caused by LPS after chronic ethanol administration. The Lieber-Decarli model of chronic alcohol administration was chosen for this study because this model has been used previously to study effects of alcohol exposure on both the liver (Lieber et al. 1965; Dolganiuc et al. 2009; Barnes et al. 2013) and lung (Velasquez et al. 2002; Joshi et al. 2005), albeit separately. Systemic LPS administration served as an inflammatory stimulus to induce hepatic inflammation and an ARDS-like phenotype in the lung (Reutershan and Ley 2004).

The effects of the Lieber-DeCarli rodent model of ethanol exposure on the liver is well-characterized and is predominated by hepatic steatosis (Lieber et al. 1965). Six weeks of exposure to the Lieber-Decarli diet does not cause overt liver injury or hepatic inflammation (Lieber et al. 1965), but sensitizes the liver to other toxic stimuli. In this 2-hit model, ethanol pre-exposure enhanced liver injury and inflammation, which corroborates previous findings in this model. Ethanol exposure has been shown to prime immune cells, including Kupffer cells, to release cytotoxic mediators including TNFα after stimulus (McClain & Cohen 1989; Enomoto et al. 1998). In this study enhanced liver injury correlated with enhanced mRNA expression and plasma levels of TNFα in response to LPS; although likely not the sole source of elevated TNFα in plasma, previous studies indicate that hepatic Kupffer cells are predominant (Bautista et al. 1994).

Chronic exposure to ethanol does not cause overt changes in the lung, however, similar to the liver, chronic ethanol exposure primes the lung to a second hit. Acute lung injury is associated with increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Ward 1996) in the lung and neutrophil migration into the interstitium (Abraham 2003). In this study, ethanol pre-exposure enhanced alveolar septal thickening and neutrophil infiltration caused by LPS (Figure 2). Studies have shown that neutrophil migration into the lung is at least partially mediated by the chemokines MIP-2 and KC (Lomas-Neira et al. 2004). Indeed, both MIP-2 and KC have been linked to acute lung injury caused by systemic LPS (Wang et al. 2013; Su et al. 2014) by mediating neutrophil recruitment via activation of CXCR2 (Reutershan et al. 2006). The work presented here shows that LPS-induced MIP-2 and KC expression in the lung was enhanced by ethanol exposure. Furthermore, increases in these chemokines correlated with increased neutrophil recruitment. Interestingly, increased expression of MIP-2 and KC in the lung and BALF have been shown to be downstream of TNFα signaling (Saperstein et al. 2009), which was not enhanced by ethanol pre-exposure in the lung in our model (Figure 4A). In contrast, hepatic TNFα mRNA expression and systemic levels of TNFα were enhanced by the combination of ethanol + LPS (Figure 3A). As mentioned previously, the role of Kupffer cell-derived TNFα in liver injury is well recognized (Adachi et al. 1994; Kono et al. 2005), however some studies have suggested that hepatic-derived TNFα contributes to pulmonary injury. For example, Kono et al demonstrated that depletion of hepatic Kupffer cells protected against pulmonary inflammation and injury and correlated with decreased hepatic TNFα expression (Kono et al. 2005). These findings suggest that systemic inflammation mediated, at least in part, by increased release of TNFα by hepatic macrophages (i.e. Kupffer cells), may be responsible for driving pulmonary MIP-2 and KC expression, and subsequent pulmonary injury, as presented here.

In order to determine the role of systemic/hepatic TNFα in enhanced pulmonary injury, the effect of depleting systemic TNFα with etanercept was determined. Etanercept is a fusion protein of the human p75 TNF receptor and the Fc portion of human IgG1. This TNFα binding antibody has been approved by the FDA for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Etanercept was used to investigate the role of systemic TNFα in this study because, while etanercept is able to reach lung, the apparent volume of distribution of the drug suggests that it locates primarily to the plasma compartment, allowing binding of systemic TNFα. In the work presented here, etanercept administration resulted in a 1.7 and 1.9 fold decrease in systemic and pulmonary TNFα levels, respectively, compared to animals that were exposed to ethanol + LPS in the absence of etanercept. This incomplete blocking of systemic and pulmonary TNFα was likely due to the robust increase in TNFα caused by systemic LPS administration, particularly in the plasma; in fact, LPS administration caused more than a 10 fold increase in systemic TNFα levels compared to their vehicle-treated, ethanol-fed counterparts. Despite the lack of complete TNFα knockdown, etanercept decreased TNFα levels in the plasma by >100 pg/mL.

Etanercept under these conditions provided partial protection against inflammatory injury in the lung caused by the combination of ethanol and LPS. Etanercept administration blunted enhanced MIP-2 and KC levels in the lung, resulting in a 1.6 and 3.5 fold decrease, respectively. These results support previous findings that TNFα signaling was upstream of enhanced MIP-2 expression in experimental ARDS (Pryhuber et al. 2003). The authors of that study showed that TNFR1−/− mice were partially protected against increased MIP-2 expression in a model of acute lung injury (Pryhuber et al. 2003). Whereas the protective effect of TNFα depletion was significant, it was not complete. Indeed, TNFα is likely one of several factors that may contribute to the ‘alcoholic lung phenotype. For example, PAI-1 has been linked to liver and lung injury (Idell 2002; Beier et al. 2009) and was differentially affected by ethanol pre-exposure in this model. Additionally, oxidative stress and transitional tissue remodeling are known to play important roles in liver injury and inflammation. Therefore, complete protection against injury in either organ will likely require multiple interventions or an intervention that protects against multiple mechanisms of injury (i.e., Kupffer cell blockade). Nevertheless, these results establish a strong link between systemic TNFα and lung damage in this model of ethanol-enhanced ALI.

As mentioned above, the priming effect of ethanol on the hepatic inflammatory response is well established. In contrast, the effect of ethanol exposure on lung has predominantly focused on impaired bacterial clearance and subsequent increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections (Greenberg et al. 1994; Boe et al. 2003). Indeed, others have shown that ethanol preexposure impairs alveolar macrophage function and inflammatory cytokine release (Zhang et al. 2002; Joshi et al. 2005). However, there are two important differences between the current study and those that have reported decreased immune response after alcohol. Specifically, the timing of LPS administration has been shown to play an important role in alcohol-induced liver injury. Previous studies have shown that if LPS is administered during acute alcohol intoxication (or w/in 1 day of a bolus dose of alcohol), the hepatic inflammatory response is blunted. In contrast, if LPS is given distal to alcohol intoxication, the inflammatory response is synergized (Enomoto et al. 1998). Many studies that have documented a decrease in pulmonary immune response in the context of alcohol exposure used acute models of intoxication in which LPS was administered within hours of alcohol exposure (Greenberg et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 1997; Quinton et al. 2005). Others have shown that chronic alcohol exposure can enhance pulmonary inflammation post-intoxication. For example, a recent study by Liu et al showed that chronic ethanol exposure enhances the pulmonary inflammatory response caused by insult (Liu et al. 2013). Additionally, Boe et al showed that chronic ethanol exposure enhances LPS-induced neutrophil migration, as was observed in the current study (Boe et al. 2010). Therefore it is likely that the timing of a stimulus – whether during intoxication or distal to intoxication – plays a critical role in pulmonary response after alcohol exposure. This timing effect could create a ‘perfect storm’ in the lung that clearance of infection is impaired during alcohol intoxication, but the inflammatory response and normal tissue damage caused by that infection is enhanced later. Such a paradigm would explain the fact that ethanol exposure increases both the incidence of lung infections and the likelihood of developing ARDS in response to a lung infection in the human population.

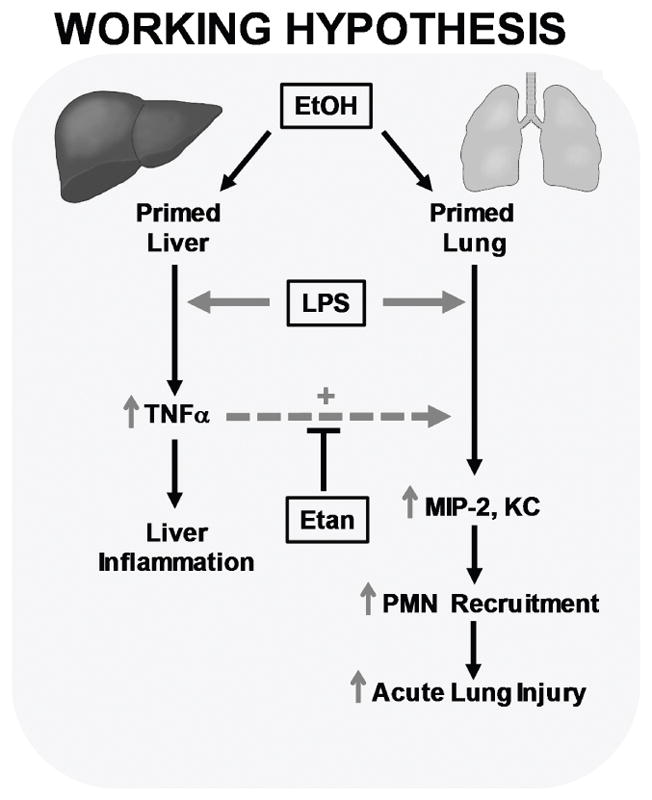

In conclusion, the current study characterizes a model of alcohol-induced liver and lung sensitization that enhances injury caused by systemic LPS. These data suggest that the pulmonary response to ethanol is dependent on systemic release of TNFα, potentially derived from hepatic macrophages (Figure 6). Additionally, although ethanol preexposure enhanced both liver and lung inflammation, both organs experienced a unique proinflammatory cytokine profile indicating that similar, yet distinct, mechanisms may be contributing to injury in these two organs. Other studies have suggested that injury to the liver and lung may be linked, potentially via systemic mediators such as TNFα. Enhanced MIP-2 and KC expression in the lung, without a concomitant increase in pulmonary TNFα further support a potential role for systemically-derived TNFα as a mediator of pulmonary injury in this model. Since etanercept is already approved for human use for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, the translational value of these findings is high.

Figure 6. Working hypothesis.

This work supports the hypothesis that systemic TNFα plays an important role in enhanced pulmonary injury caused by the combination of chronic ethanol exposure and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Ethanol preexposure primes both the liver and lung to enhanced injury and inflammation caused by LPS. In the work presented here, ethanol preexposure significantly enhanced LPS induced TNFα mRNA expression in the liver but not the lung. Interestingly, ethanol preexposure enhanced LPS induced increases in the TNFα responsive genes MIP-2 and KC in the lung.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part by NIH grants R01AA021978 (GEA, PI) and R01AA013353 (JR, PI) and by an internal grant from the University of Louisville. VLM was supported by a predoctoral fellowship (T32ES011564).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–S199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi Y, Bradford BU, Gao W, Bojes HK, Thurman RG. Inactivation of Kupffer cells prevents early alcohol-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 1994;20:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes MA, McMullen MR, Roychowdhury S, Pisano SG, Liu X, Stavitsky AB, Bucala R, Nagy LE. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor contributes to ethanol-induced liver injury by mediating cell injury, steatohepatitis, and steatosis. Hepatology. 2013;57:1980–1991. doi: 10.1002/hep.26169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP, Skrepnik N, Niesman MR, Bagby GJ. Elimination of macrophages by liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate suppresses the endotoxin-induced priming of Kupffer cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:321–327. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara RI, Brown LA, Eaton DC, Roman J, Guidot DM. Chronic ethanol ingestion increases expression of the angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptor and enhances tumor necrosis factor-alpha- and angiotensin II-induced cytotoxicity via AT2 signaling in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1006–1014. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000071932.56932.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier JI, Luyendyk JP, Guo L, von Montfort C, Staunton DE, Arteel GE. Fibrin accumulation plays a critical role in the sensitization to lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury caused by ethanol in mice. Hepatology. 2009;49:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/hep.22847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe DM, Nelson S, Zhang P, Quinton L, Bagby GJ. Alcohol-induced suppression of lung chemokine production and the host defense response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1838–1845. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000095634.82310.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe DM, Richens TR, Horstmann SA, Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Henson PM, Moss M, Vandivier RW. Acute and chronic alcohol exposure impair the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and enhance the pulmonary inflammatory response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1723–1732. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinger GR, McKell JL, Urich D, Foiles N, Weiss I, Chiarella SE, Gonzalez A, Soberanes S, Ghio AJ, Nigdelioglu R, Mutlu EA, Radigan KA, Green D, Kwaan HC, Mutlu GM. Particulate matter-induced lung inflammation increases systemic levels of PAI-1 and activates coagulation through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham EL, Moss M, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J. Increased fibronectin expression in lung in the setting of chronic alcohol abuse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:675–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins CM, Heimbach JK, Bensard DD, Song Y, Raeburn CD, Meng X, McIntyre RC., Jr TNF receptor I mediates chemokine production and neutrophil accumulation in the lung following systemic lipopolysaccharide. J Surg Res. 2001;101:232–237. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza NB, Baustista AP, Lang CH, Spitzer JJ. Acute ethanol intoxication prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced down regulation of protein kinase C in rat Kupffer cells. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:64–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Petrasek J, Kodys K, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, Velayudham A, Szabo G. MicroRNA expression profile in Lieber-DeCarli diet-induced alcoholic and methionine choline deficient diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis models in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1704–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto N, Ikejima K, Bradford BU, Rivera CA, Kono H, Brenner DA, Thurman RG. Alcohol causes both tolerance and sensitization of rat Kupffer cells via mechanisms dependent on endotoxin. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SS, Xie J, Wang Y, Kolls J, Malinski T, Summer WR, Nelson S. Ethanol suppresses LPS-induced mRNA for nitric oxide synthase II in alveolar macrophages in vivo and in vitro. Alcohol. 1994;11:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann P, Chen WC, Schnabl B. The intestinal microbiome and the leaky gut as therapeutic targets in alcoholic liver disease. Front Physiol. 2012;3:402. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00402. Epub;%2012 Oct 11., 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idell S. Endothelium and disordered fibrin turnover in the injured lung: newly recognized pathways. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S274–S280. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, Ramirez AM, Ritzenthaler JD, Torres-Gonzalez E, Roser-Page S, Mora AL, Brigham KL, Jones DP, Roman J, Rojas M. Oxidation of extracellular cysteine/cystine redox state in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L37–L45. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90401.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi PC, Applewhite L, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J, Fernandez AL, Eaton DC, Brown LA, Guidot DM. Chronic ethanol ingestion in rats decreases granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor expression and downstream signaling in the alveolar macrophage. J Immunol. 2005;175:6837–6845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabela SP, Kairi CA, Magkouta S, Psallidas I, Moschos C, Stathopoulos I, Zakynthinos SG, Roussos C, Kalomenidis I, Stathopoulos GT. Neutralization of tumor necrosis factor bioactivity ameliorates urethane-induced pulmonary oncogenesis in mice. Neoplasia. 2011;13:1143–1151. doi: 10.1593/neo.111224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanlou H, Souto H, Lippmann M, Munoz S, Rothstein K, Ozden Z. Resolution of adult respiratory distress syndrome after recovery from fulminant hepatic failure. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:134–136. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono H, Fujii H, Amemiya H, Asakawa M, Hirai Y, Maki A, Tsuchiya M, Matsuda M, Yamamoto M. Role of Kupffer cells in lung injury in rats administered endotoxin 1. J Surg Res. 2005;129:176–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber CS, Jones DP, DeCarli LM. Effects of prolonged ethanol intake: Production of fatty liver despite adequate diets. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1965;44:1009–1021. doi: 10.1172/JCI105200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YD, Liu W, Liu Z. Influence of long-term drinking alcohol on the cytokines in the rats with endogenous and exogenous lung injury. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas-Neira JL, Chung CS, Grutkoski PS, Miller EJ, Ayala A. CXCR2 inhibition suppresses hemorrhage-induced priming for acute lung injury in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:58–64. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuschak GM. Lung-liver interactions in sepsis and multiple organ failure syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:83–98. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuschak GM, Mattingly ME, Tredway TL, Lechner AJ. Liver-lung interactions during E. coli endotoxemia. TNF-alpha:leukotriene axis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:41–49. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1989;9:349–351. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE. The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. JAMA. 1996;275:50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Kolls JK. Alcohol, host defence and society. Nature Rev Immunol. 2002;2:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nri744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryhuber GS, Huyck HL, Baggs R, Oberdorster G, Finkelstein JN. Induction of chemokines by low-dose intratracheal silica is reduced in TNFR I (p55) null mice. Toxicol Sci. 2003;72:150–157. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton LJ, Nelson S, Zhang P, Happel KI, Gamble L, Bagby GJ. Effects of systemic and local CXC chemokine administration on the ethanol-induced suppression of pulmonary neutrophil recruitment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1198–1205. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171927.66130.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutershan J, Ley K. Bench-to-bedside review: acute respiratory distress syndrome - how neutrophils migrate into the lung. Critical Care. 2004;8:453–461. doi: 10.1186/cc2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutershan J, Morris MA, Burcin TL, Smith DF, Chang D, Saprito MS, Ley K. Critical role of endothelial CXCR2 in LPS-induced neutrophil migration into the lung. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:695–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI27009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenfeld G, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin D, Neff M, Stern E, Hudson L. Incidence and Outcomes of Acute Lung Injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;53:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saperstein S, Huyck H, Kimball E, Johnston C, Finkelstein J, Pryhuber G. The effects of interleukin-1beta in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced acute pulmonary inflammation in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:958658. doi: 10.1155/2009/958658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siore AM, Parker RE, Stecenko AA, Cuppels C, McKean M, Christman BW, Cruz-Gervis R, Brigham KL. Endotoxin-induced acute lung injury requires interaction with the liver. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L769–L776. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00137.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su ZQ, Mo ZZ, Liao JB, Feng XX, Liang YZ, Zhang X, Liu YH, Chen XY, Chen ZW, Su ZR, Lai XP. Usnic acid protects LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice through attenuating inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;22:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Bala S. Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1321–1329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2010 [Google Scholar]

- US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez A, Bechara RI, Lewis JF, Malloy J, McCaig L, Brown LA, Guidot DM. Glutathione replacement preserves the functional surfactant phospholipid pool size and decreases sepsis-mediated lung dysfunction in ethanol-fed rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000024269.05402.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Montfort C, Beier JI, Guo L, Kaiser JP, Arteel GE. Contribution of the sympathetic hormone epinephrine to the sensitizing effect of ethanol on LPS-induced liver damage in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1227–G1234. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Huang X, Li Y, Guo K, Ning P, Zhang Y. PARP-1 inhibitor, DPQ, attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting NF-kappaB-mediated inflammatory response. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PA. Role of complement, chemokines, and regulatory cytokines in acute lung injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;796:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Bagby GJ, Boe DM, Zhong Q, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK, Summer WR, Nelson S. Acute alcohol intoxication suppresses the CXC chemokine response during endotoxemia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Nelson S, Summer WR, Spitzer JA. Acute ethanol intoxication suppresses the pulmonary inflammatory response in rats challenged with intrapulmonary endotoxin. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:773–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]