Abstract

We describe two patients with HIV/AIDS who presented pulmonary and intestinal infection caused by Cryptosporidium parvum, with a fatal outcome. The lack of available description of changes in clinical signs and radiographic characteristics of this disease when it is located in the extra-intestinal region causes low prevalence of early diagnosis and a subsequent lack of treatment.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Cryptosporidiosis, Pneumonia, Cryptosporidium parvum

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidium parvum is an obligate intracellular parasite of the Coccidia class that infects the microvilli epithelial cells of the digestive and respiratory systems1. This parasite is responsible for causing severe diarrhea in approximately 55% of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) patients living in developing countries2.

Among the 16 currently described species of Cryptosporidium, C. parvum and C. hominis are those that predominate in immunocompromised individuals3.

Infection occurs after ingestion of water or food contaminated with oocysts or direct person-to-person or animal-person contact4. Respiratory forms of infection can happen upon inhalation of oocysts during an episode of vomiting5 , 6.

Studies by LOPEZ-VELEZ et al. 7 and CLAVEL et al. 8 found that 30.2% of patients with intestinal cryptosporidiosis also carried extraintestinal infections in both the lungs and bile. The studies mentioned above reported high mortality rates amongst the patients as these cases showed dramatically lower CD4 + cell counts, ultimately reflecting a very severe degree of immunosuppression.

Therefore, we decided it to be of clinical and educational significance to report our finding of C. parvum (identified by molecular testing) in fecal samples and sputum from two HIV/AIDS patients.

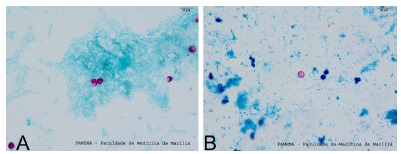

This study was submitted and approved by the Research on Human Beings Ethics Committee of the Marília Medical School (FAMEMA), under the number 33677514.1.0000.5413. Figure 2 was made using the medical records of patients what are in the custody of the Serviço de Prontuário de Paciente (SPP) of Marília Medical School. Similarly, the blades for the manufacture of Figure 3 were photomicrographed in Olympus microscope BX41 model coupled to a digital video camera, Olympus, DP 25 model, DP2-BSW software, Olympus, originals of FAMEMA Parasitology and Microbiology Laboratories.

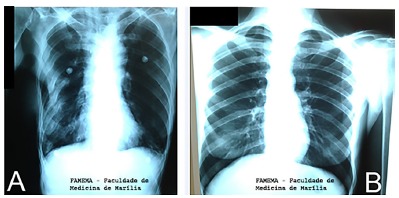

Fig. 2. - A: Nonspecific radiographic changes presented by Patient 1. B: Patient 2 without significant radiographic changes.

Fig. 3. - A: Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts in faeces stained by the Kinyoun method.B: Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts in sputum stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen method.

Patient history

Case 1:

On 10/06/2013, a fifty-nine-year-old female patient sought medical care at the emergency ward of the Marilia Clinical Hospital. The patient reported a two-month-long history of diarrhea, along with oral moniliasis associated with weight loss of 15 kg +/- over this period. She denied any fever, cough, urinary changes or emesis. The patient reported one prior medical consultation within Brazil's Specialized Care Service (SAE) with the same story and referring indication of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), however, without any confirmed CD4 + result.

On the day of treatment, the patient had a physical examination that determined a poor general condition: pale; dehydrated; Heart rate: 68 bpm; Blood pressure: 80 x 50 mmhg; afebrile.

Lungs: Vesicular murmur: present with bibasilar crepitant rales.

Heart: S1 and S2 heart sounds normal and regular; without murmurs.

Abdomen: excavated, bowel sounds present and hypoactive, limp and painless.

Lower limb: weak pulse, with capillary refill time: 3 seconds.

At this time, supportive measures were instituted, including a broad spectrum treatment for opportunistic diseases. Laboratory tests were requested, including for detection of Cryptosporidium spp., which ultimately proved positive in both stool samples (method Kinyoun) and sputum (the Ziehl-Neelsen).

Case 2:

On 10/18/2013, a forty-four-year-old female patient was admitted to the Infectious Diseases Ward of Marilia Clinical Hospital. The patient reported experiencing diarrhea for approximately the previous three months. During this period, the patient experienced a weight loss of 10 kg, associated with an unmeasured fever and dry cough. On the day of admission, the patient presented a normal general condition: conscious, oriented, dehydrated and pale. Heart: S1 and S2 heart sounds normal; without murmur Heart rate: 86 bpm, Lungs: Vesicular murmur: present, no adventitious sounds (Saturation: 98%).

Supportive measures and laboratory tests were performed.

Treatment of esophageal candidiasis was initiated upon hospitalization. An Acid-Alcohol Resistant Bacilli (AARB) exam was performed with negative results, and the analysis of stool and sputum samples forCryptosporidium returned positive.

Molecular testing: Stool and sputum samples from both patients were submitted to a specific detection of Cryptosporidium using Nested PCR method. The fragment of the 18S rRNA subunit was amplified by nested PCR by using the forward primers: SCL1F 5'-CTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGTAG-3' and reverse CPB-DIAGR 5'-AAGGTGCTGAAGGAGTAAGG-3' which amplify 1035 pb and SSU F 5'-GGAAGGGTTTTTATTGTAAGATAAAG-3' and SSUR 5'-AAGGAGTAA GGATCCACCACAA- 3' which amplify about 826 pb as previously described by COUPE et al. 9 and XIAO et al. 10 to identify ofCryptosporidium spp. The fragments of the secondary PCR were purified with GFXTM PCR DNA Gel Band Purification Kit (GE-UK) and directly sequenced. The nucleotide sequences obtained were analyzed and compared with those registered in GenBank, and phylogenetic analysis were used on the aligned sequences to assess relationships among sequences that allowed the identification of Cryptosporidium parvum in both patients.

DISCUSSION

The low number of diagnosed cases of extraintestinal cryptosporidiosis, especially of pulmonary location, is largely due to the absence of specific clinical signs, as well as the presence of radiological abnormalities, which can be confused with other opportunistic infections that commonly affect patients with immune impairment.

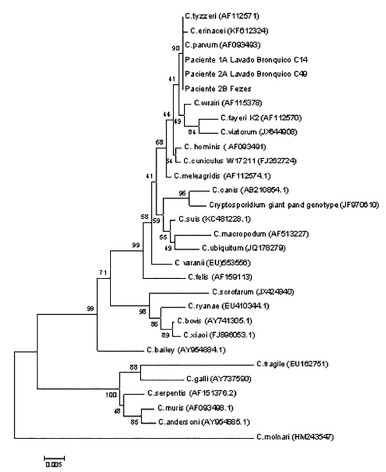

In our cases, parasitological examination by Ziehl-Neelsen and Kinyoun techniques demonstrated the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. in the sputum and stool (Fig. 3) of two patients. Confirming the presence of the specific species, C. parvum, was performed by nested PCR of the 18S rRNA region in sputum and feces of patient 2, and sputum of patient 1. Sequencing of the samples was then performed and aligned with the sequences available in the GenBank database, showing similarity with the C. parvum species, as can be observed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. - A phylogenetic tree was inferred using the neighbor-joining method28 with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and evolutionary distances calculated using the Kimura 2-parameter29 method. Evolutionary analyzes were performed by MEGA5 software30.

There is no sufficient molecular data available to support information on the prevalence of C. parvum in clinical cases in Brazil. ASSISet al. 11 detectedCryptosporidium parvum in 10 HIV-positive patients inMinas Gerais, suggesting a possible zoonotic transmission of this species of Cryptosporidium. However, many studies showed thatC. hominis, along with C. parvum, are the most frequent species observe in humans worldwide12 , 13.

The differentiation of Cryptosporidium to species level depends on the identification by specifics molecular methods, which limits the availability of information on the spread of this species of Cryptosporidium in human clinical cases, mainly in Brazil12. Therefore, the epidemiological importance of reporting these cases is bolstered by the fact that the transmission of this parasite occurs from person-person14, since certain promiscuous habits can happen primarily amongst practitioners of oro-anal intercourse, putting these individuals at specific risk of infection12 , 15 , 16.

Although the results demonstrated the presence of C. parvum in stool and sputum, indicating the possibility that pulmonary infection has occurred through inhalation of oocysts during an episode of vomiting, as mentioned by some authors6, one cannot rule out the spread by hematogenous route, since it is described as the presence of the parasite within macrophages17.

GENTILE et al. 18 reported finding Cryptosporidium oocysts within blood vessels and studies of MARTINEZ et al. 19 in anin vitro study conducted in mice, demonstrated thatCryptosporidium can multiply within macrophages, resisting the action of lysosomal enzymes, making it difficult to control the infection in immunocompromised patients in case that this possibility occurred in humans.

Although radiographic changes occurred only in Patient 1, (Fig. 2), specific treatment for cryptosporidiosis was not instituted, because until then there was no effective treatment for cryptosporidiosis in HIV/AIDS patients. Several authors showed the limited effectiveness of drugs like Nitazoxanide, Macrolides, or Paromomycin for treating cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients, even if HAART was associated20 , 21 , 22 , 23. Recently, promising results have been obtained by CASTELLANOS-GONZALEZ et al. (2013)24 when they treated immunosuppressed mice infected withC. parvum using Calcium-dependent protein kinases inhibitor (CDPK1 inhibitor).

Therefore at this time, we choose to treat the most prevalent infectious diseases in these patients, and antiretroviral therapy HAART was initiated to recovery the cellular immune system25, since CD4+ cells are decisive for the acquired immune response26. However, in a short space of time, there was a worsening of the general condition of Patient 1, and she progressed to death. In relation to Patient 2, as she had been clinically stable, the patient was discharged with guidelines for outpatient follow-up and established HAART. However, the patient did not return to her scheduled consultations, resulting in an interruption in medical care and, consequently, the maintenance treatment, leading to a fatal outcome.

Seeing as a pulmonary infection, it is considered a rare complication in its intestinal form27, combined with the high mortality rate of these cases, the lack of formal description of clinical and radiographical changes seen upon extra-intestinal localization of this parasite, cause an extremely low rate of early diagnosis and untimely treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Current WL, Garcia LS. Cryptosporidiosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:325–358. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soto M, Velásquez G, Cuervo C, Galvis MT, Botero D. Criptosporidiosis respiratoria en un paciente con SIDA. Acta Med Colomb. 1997;22:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meamar AR, Guyot K, Certad G, Dei-Cas E, Mohraz M, Mohebali M. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans and animals in Iran. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1033–1035. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00964-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosek M, Alcantara C, Lima AA, Guerrant RL. Cryptosporidiosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:262–269. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albuquerque YM, Silva MC, Lima AL, Magalhães V. Pulmonary cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients, an underdiagnosed disease. J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38:530–532. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132012000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corti M, Villafañe MF, Muzzio E, Bava J, Abuín JC, Palmieri OJ. Pulmonary cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2008;40:106–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López-Vélez R, Tarazona R, Garcia Camacho A, Gomez-Mampaso E, Guerrero A, Moreira V. Intestinal and extraintestinal cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:677–681. doi: 10.1007/BF01690873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clavel A, Arnal AC, Sánchez EC, Cuesta J, Letona S, Amiguet JA. Respiratory cryptosporidiosis: case series and review of the literature. Infection. 1996;24:341–346. doi: 10.1007/BF01716076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coupe S, Sarfati C, Hamane S, Derouin F. Detection of Cryptosporidium and identification to the species level by nested PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1017–1023. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1017-1023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao L, Alderisio K, Limor J, Royer M, Lal AA. Identification of species and sources of Cryptosporidium oocysts in storm waters with a small-subunit rRNA-based diagnostic and genotyping tool. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5492–5498. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5492-5498.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assis DC, Resende DV, Cabrine-Santos M, Correia D, Oliveira-Silva MB. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp: and Cystoisospora belli in HIV-infected patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013;55:149–154. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalmers RM, Davies AP. Minireview: clinical cryptosporidiosis. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucca P, De Gaspari EN, Bozzoli LM, Funada MR, Silva SO, Iuliano W. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp: from HIV infected patients from an urban area of Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:341–343. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araújo AJ, Kanamura HY, Almeida ME, Gomes AH, Pinto TH, Da Silva AJ. Genotypic identification of Cryptosporidium spp: isolated from HIV-infected patients and immunocompetent children of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50:139–143. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652008005000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachur TP, Vale JM, Coêlho IC, Queiroz TR, Chaves CS. Enteric parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients before and after the highly active antiretroviral therapy. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:115–122. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702008000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keystone JS, Keystone DL, Proctor EM. Intestinal parasitic infections in homosexual men: prevalence, symptoms and factors in transmission. Can Med Assoc J. 1980;123:512–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma P, Villanueva TG, Kaufman D, Gillooley JF. Respiratory cryptosporidiosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Use of modified cold Kinyoun and Hemacolor stains for rapid diagnoses. JAMA. 1984;252:1298–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentile G, Baldassarri L, Caprioli A, Donelli G, Venditti M, Avvisati G. Colonic vascular invasion as a possible route of extraintestinal cryptosporidiosis. Am J Med. 1987;82:574–575. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90474-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez F, Mascaro C, Rosales MJ, Diaz J, Cifuentes J, Osuna A. In vitro multiplication of Cryptosporidium parvum in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Vet Parasitol. 1992;42:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(92)90099-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abubakar I, Aliyu SH, Arumugam C, Hunter PR, Usman NK. Prevention and treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD004932–CD004932. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabada MM, White AC., Jr Treatment of cryptosporidiosis: do we know what we think we know? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:494–499. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833de052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Checkley W, White AC, Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurniawan A, Dwintasari SW, Connelly L, Nichols RA, Yunihastuti E, Karyadi T. Cryptosporidium species from human immunodeficiency-infected patients with chronic diarrhea in Jakarta, Indonesia. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:720–723. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellanos-Gonzales A, White AC, Jr, Ojo KK, Vidadala RS, Zhang Z, Reid MC. A novel calcium-dependent protein kinase inhibitor as a lead compound for treating cryptosporidiosis. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1342–1348. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao YM, Awad-El-Kariem FM, Franzen C, Ellis DS, Müller A, Counihan HM. Eradication of cryptosporidia and microsporidia following successful antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:124–129. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patenburg B, Dann SM, Wang HC, Robinson P, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Lewis DE. Intestinal immune response to human Cryptosporidium sp: infection. Infect Immun. 2008;76:23–29. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00960-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dupont C, Bougnoux ME, Turner L, Rouveix E, Dorra M. Microbiological findings about pulmonary cryptosporidiosis in two AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:227–229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.227-229.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]