Abstract

Background

National guidelines in the UK, United States of America, Canada, and Australia have recently stressed the importance of identifying and treating antenatal anxiety and depression. However, there is little research into the most effective and acceptable ways of helping women manage their symptoms of anxiety and stress during pregnancy. Research indicates the necessity to consider the unique needs and concerns of perinatal populations to ensure treatment engagement, highlighting the need to develop specialised treatments which could be integrated within routine antenatal healthcare services. This trial aims to develop a brief intervention for antenatal anxiety, with a focus on embedding the delivery of the treatment within routine antenatal care.

Methods/Design

This study is a two-phase feasibility trial. In phase 1 we will develop and pilot a brief intervention for antenatal anxiety, blended with group support, to be led by midwives. This intervention will draw on cognitive behavioural principles and wider learning from existing interventions that have been used to reduce anxiety in expectant mothers. The intervention will then be tested in a pilot randomised controlled trial in phase 2. The following outcomes will be assessed: (1) number of participants meeting eligibility criteria, (2) number of participants consenting to the study, (3) number of participants randomised, (4) number of sessions completed by those in the intervention arm, and (5) number of participants completing the post-intervention outcome measures. Secondary outcomes comprise: detailed feedback on acceptability, which will guide further development of the intervention; and outcome data on symptoms of maternal and paternal anxiety and depression, maternal quality of life, quality of couple relationship, mother-child bonding, infant temperament and infant sleep.

Discussion

The study will provide important data to inform the design of a future full-scale randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention for anxiety during pregnancy. This will include information on its acceptability and feasibility regarding implementation within current antenatal services, which will inform whether ultimately this provision could be rolled out widely in healthcare settings.

Trial registration

Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN95282830. Registered on 29 October 2014.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1274-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antenatal, Anxiety, Group intervention, Cognitive behavioural therapy, Feasibility

Background

Clinically significant levels of anxiety symptoms are experienced by up to half of all women during pregnancy [1], with a high proportion suffering diagnosed anxiety disorders [2–4]; prevalence estimates for generalised anxiety disorder in pregnancy range from 0 to 10.5 % [4]. Furthermore, antenatal anxiety is a strong predictor of postnatal anxiety and depression [3, 5, 6]. There is now a substantial body of evidence from observational cohort studies demonstrating that elevated anxiety in mothers during pregnancy is also associated with an increased risk of a range of short- and long-term adverse outcomes in their children [7] and poorer obstetric outcomes [8]. These include higher rates of preterm delivery [8, 9], and effects on child outcomes such as difficult temperament [10, 11], increased sleep problems [12], poorer cognitive functioning [13], and higher rates of emotional and behavioural problems in early childhood that often persist into later development [7].

National guidelines in the UK [14], the United States of America [15, 16], Canada [17], and Australia [18–20] have recently stressed the crucial importance of identifying and offering treatment for antenatal anxiety and depression. These guidelines have recommended screening for all women as a routine part of antenatal care, along with timely access to appropriate services for assessment and psychological intervention in pregnancy [14–20]. These recommendations were made despite the lack of evidence to guide the direction of treatment for women who have anxiety during pregnancy and the absence of systematic research examining the impact of treating antenatal anxiety on maternal and infant outcomes. This missing link is critical, as the potential opportunity for preventive intervention is large, given the substantial neural, cognitive and socio-emotional developments that occur in the fetal period and the first years of life [7], and potential for recurrent problems in the mother.

It is, therefore, crucial that effective and cost-effective treatments are developed for antenatal anxiety. Recent research strongly suggests that perinatal populations have unique concerns, and that considering the specific needs of perinatal populations is essential to ensure treatment engagement [21–23]. Any treatment for antenatal anxiety must, therefore, be acceptable and relevant to pregnant women, addressing their specific anxieties and unique circumstances and needs during this period. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has been subject to rigorous evaluation and has a strong evidence base for the effective treatment of anxiety disorders [24], including in a guided self-help format [25], but a specific literature investigating the utility of CBT approaches for treating anxiety during pregnancy is largely lacking at present [26, 27]. One of very few interventions that have been further developed and evaluated for antenatal mood difficulties is Towards Parenthood [28]. This is a guided self-help intervention designed to help expectant parents prepare for parenthood, which has been developed by Milgrom, Ericksen and colleagues in Australia. This has been tested in a clinical trial [28] and showed promising results, with significant reductions in symptoms of both anxiety and depression at postnatal follow-up compared to routine care.

Recent research has also highlighted the impact that partners have on child development and family functioning [29], and the importance of social support during pregnancy, since this is associated with lower maternal antenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety [6, 30, 31]. More recent policy documents have indicated that pregnancy is an important opportunity to engage partners [32] and have recommended the inclusion of fathers in care and intervention from the antenatal period [33], suggesting that interventions for maternal mental health in the perinatal period should also consider the potential inclusion of partners.

The advantages of intervening in the antenatal period to reduce maternal anxiety are threefold: first, the psychological treatment is delivered in a context in which mothers are already experiencing a high level of contact with healthcare services and frequently attend routine antenatal classes; second, antenatal treatment could reduce the possible negative effects of antenatal anxiety on fetal development; and third, given the associations between antenatal anxiety and postnatal depression and anxiety [3, 5, 6], antenatal intervention offers the potential to prevent some episodes of postnatal depression and anxiety and so to improve maternal wellbeing, as well as reduce the developmental risk to the child of exposure to maternal postnatal depression and anxiety.

Our research proposes the development and testing of an intervention tailored specifically for use with pregnant women experiencing antenatal anxiety, based on CBT principles and incorporating key learning from the Towards Parenthood team, for use in a group format led by midwives, in the context of UK antenatal services. Embedding the intervention in routine antenatal care in a brief midwife-led group format means that it has the potential to be a cost-effective mode of delivery and one that is robust to changing healthcare environments, requiring less time and input from midwives than an individual psychological approach and being widely available to women experiencing difficulties with anxiety. It therefore has the potential to improve outcomes for a wide range of pregnant women and their infants, thereby reducing the overall population burden of anxiety during pregnancy. Given the existing national guidelines, the results of the proposed trial could be crucial in informing the development of clinical services.

Aims and objectives

Following the Medical Research Council guidelines for developing and testing complex interventions [34, 35], the purpose of this research is to assess the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a midwife-led group intervention to reduce levels of anxiety in pregnant women. The objective of phase 1 is to develop an intervention, based on the principles outlined above, for use in the UK in a group setting led by midwives. The objective of phase 2 is to conduct a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing the group intervention with treatment as usual. Outcomes will assess: the feasibility and acceptability of recruitment and data collection methods; the acceptability of intervention materials and delivery; likely recruitment and retention rates; and estimates of the range of effect sizes. We will use this information to inform a fully powered RCT.

Methods/Design

Study design

The study consists of two phases. Phase 1 is a development stage in which a brief intervention for anxiety will be developed, adapted for pregnancy, drawing on core CBT principles and learning from the team that developed the Towards Parenthood intervention [28]. We will develop an intervention for delivery in group format, to be led by midwives and embedded into antenatal care in the UK. In an initial pilot group we will gather detailed feedback about the intervention content and delivery, and will use this information to inform further treatment adaptations. A mixed-methodology design will be used. If a manualised intervention can be successfully developed and delivered to a pilot group in a way that is acceptable to them, and/or modified to take any key suggestions and concerns into account, we will continue to phase 2.

In phase 2, we will conduct a pilot RCT comparing the group intervention for antenatal anxiety (intervention group) with treatment as usual (control group). This protocol follows Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [36] and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) [37] (Additional file 1) guidelines for reporting clinical trial protocols.

Study setting

Participants will be recruited through UK National Health Service (NHS) antenatal scanning clinics at their 12-week scan in London and the South West of England. The intervention will be delivered to participants in these locations as a part of antenatal services.

Participant inclusion criteria

Eligible participants will be pregnant women who have not had any children, entering their second trimester, aged 18 and over. Women will be invited to participate if they score in the top quartile of scores on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) [38] at screening. The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report screening measure for anxiety symptoms, which is widely-used in clinical practice and research.

Partners of women who consent to take part in the study will also be invited to participate. Fully informed consent will be obtained from potential participants for each stage of the research.

Participant exclusion criteria

Potential participants will be excluded if: they have insufficient understanding of English to complete the intervention or outcome measures; they have a significant illness or disability that would make it difficult for them to participate.

Recruitment procedure

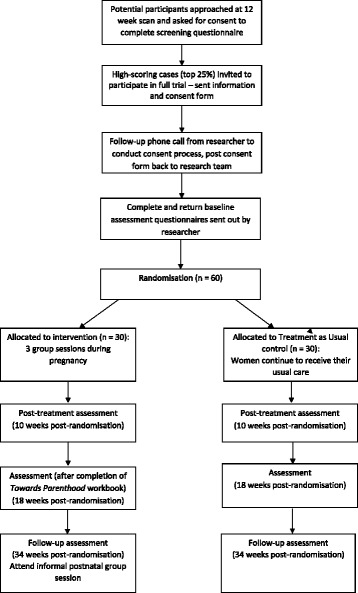

After completing the screening questionnaire for anxiety (GAD-7; [38]) and a small number of demographic questions in the antenatal scanning clinic, women who meet eligibility criteria will be sent information on the full study and a consent form. A researcher will follow up with a phone call and, if the individual is willing to take part, will guide them through the consent form. The participant will be directed to send back the signed consent form via mail or online, after which the researcher will provide the participant with the option to complete the baseline questionnaires via mail or online. Upon completion and receipt of the baseline measures, participants will be randomised (see Fig. 1). Women’s partners who agree to participate in the study will be consented separately.

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of progress through the study

All participants will be offered a £10 voucher at three time points in the study as an expression of gratitude for their participation and will be reimbursed any travel expenses incurred.

Randomisation

In phase 2, participants will be randomly allocated on a 1:1 basis to either the intervention group or the treatment as usual group using a sealed envelope method, managed by a staff member in a separate research group. Participants will be informed of their group allocation by a researcher over the telephone.

Sample size

In line with guidelines for pilot RCTs, no formal power calculation has been conducted [39]. A sample size of 30 participants per arm is recommended for feasibility studies as providing sufficient data to gain an accurate estimation of the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial methods [40], and to provide a reasonable range of estimates of the sample size required for a definitive RCT [41]. Thus, 30 participants will receive the intervention (in four groups of approximately 7–8 participants each, plus participants’ partners where possible) and 30 will receive treatment as usual.

Intervention

The research will adapt and build on existing interventions utilising CBT principles. One such intervention, Towards Parenthood, is a workbook-based, psychoeducational intervention that focuses on making the transition into parenthood and on the emotional, social and psychological issues that can arise during pregnancy and early parenthood. The Towards Parenthood intervention aims to help expectant parents develop effective coping and parenting skills. In addition, it provides specific information about anxiety, stress and mood problems and incorporates fundamental elements of CBT, which addresses maladaptive cognitions and behaviours. In a clinical trial in Australia [28] it was shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety (d = 0.58), stress (d = 0.59) and depression (d = 0.6) in women at postnatal follow-up. The workbook incorporates nine sections and women in the Australian trial additionally received weekly telephone support from trained psychologists or postgraduate psychology trainees.

The planned intervention will be developed for optimal efficacy, feasibility and acceptability with a broad population of pregnant women experiencing a range of anxiety symptoms of differing severity, with the aim of reducing the overall population burden of antenatal anxiety.

The proposed format will be a manualised brief intervention, blended with group support. We plan to deliver three group sessions in the antenatal period, led by a trained midwife and psychology supporter, with each session lasting approximately 90 minutes. Sessions will be held at 3-week intervals, which is designed to maintain participant engagement but also allow participants enough time to try out practical strategies between sessions. As a further measure to support participants and maintain engagement, the midwife and psychologist delivering the groups will also send a weekly email to each participant to remind them to practise the skills from the previous group session and to ask whether they have any questions about the material. This can be stepped up to a telephone call if there is no response from a participant or if a telephone call is requested by the participant. Telephone calls will be limited to a maximum of 15 minutes in length, unless clinical imperative dictates otherwise.

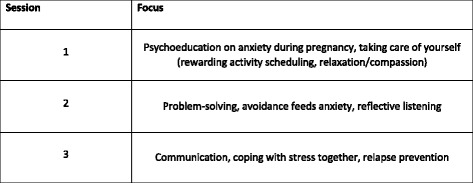

The three group sessions are designed to address specific antenatal anxieties, and will support participants in developing key practical skills. A group mode of delivery has strong potential to be more cost-effective and sustainable and less time-consuming for midwives than individual support, and will also enable mutual support and interaction between group members, thereby fitting well with the existing models of antenatal care. Furthermore, it could be easily integrated into current routine NHS antenatal services and would, therefore, be widely available and accessible to a broad range of pregnant women. The specific parameters of the intervention and its delivery will be finalised in light of the pilot work undertaken in phase 1 of the research programme, but the aim is to base the three group sessions on a number of key themes, including psychoeducation on anxiety during pregnancy, problem-solving, communication and other strategies and techniques to help with managing anxiety and stress including self-care and compassion (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Focus of midwife-led group support sessions

In the first two sessions, participants will be split into separate groups for part of the session: one group for pregnant women and the other for partners. This will allow pregnant women to work on specific skills to help with their anxiety, whilst partners will work on skills and approaches to support their pregnant partner. The remainder of each session, and the entire third session, will be delivered to the group as a whole, to allow couples to develop coping strategies together. At the end of the three group sessions support moves to be more self-led and participants will be given the full Towards Parenthood workbook to work through. There will also be a follow-up session for participants at approximately 8 weeks postnatally. This will be an informal session which will give participants a chance to meet again and to check in with the midwives.

All women in the intervention arm will continue to receive their usual care during pregnancy, and will have access to the usually available range of interventions for antenatal anxiety and other physical and mental health problems.

Control: treatment as usual

Women randomised to the control group will continue to receive their usual care for antenatal anxiety. Although there is currently no standard model of care for antenatal anxiety, this may include care provided by their general practitioner (GP), midwife, health visitor, local Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service or community mental health team. The care received by women in the trial will be actively monitored by the research group, using the Adult Service Use Scale (AD-SUS).

Assessments and outcome measures

Feasibility and acceptability

The main study outcomes will assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and study design. The primary outcome will be feasibility of recruitment and data collection, examined through assessing the following: (1) number of participants meeting eligibility criteria, (2) number of participants consenting to the study, (3) number of participants randomised, (4) number of sessions completed by those in the intervention arm, and (5) number of participants completing the post-intervention outcome measures. Furthermore, we will record reasons for study withdrawal, non-participation and non-attendance of intervention sessions.

Detailed feedback will be gathered from all participants and the midwife and psychologist delivering the intervention, in order to assess the acceptability of the intervention and trial methods. Feedback will be gained from participants allocated to the intervention arm through brief questionnaires at the end of each group session and a more detailed post-intervention feedback questionnaire. Semi-structured acceptability interviews will be conducted with a purposeful sample of participants from both study arms at post-intervention assessment. Open-ended questions will be asked about participants’ impressions of the intervention and group delivery; the relevance and suitability of the intervention content; perceived benefit of the intervention; problems or difficulties experienced with the sessions, and recommendations for changes or developments to the intervention; their experience of being a part of the study; and their impressions of current routine antenatal care. Interviews are designed to last approximately 30–60 minutes and will be conducted face-to-face. Qualitative data analysis will be conducted following the interviews.

Fidelity to the intervention manual will be examined using video and audio tapes of intervention sessions. A random sample of 10 % of therapy tapes will be assessed for fidelity by two of the investigators.

Data collection

At each assessment point, questionnaires will either be posted to participants and returned via post, or participants will be provided with a link to a website where they can complete the measures online. Measures will be collected at baseline, post intervention (10 weeks post randomisation), 8 weeks post intervention (18 weeks post randomisation), and postnatal follow-up (34 weeks post randomisation); the measures of mother-child relationship, infant temperament and infant sleep will be collected at postnatal follow-up only. Partners will also complete measures of anxiety, mood and quality of couple relationship at each assessment point.

Clinical outcome measurements

A range of clinical outcome measures will be included in order to assess the feasibility and acceptability of these measures, and estimates of levels of symptoms in both trial arms at each assessment time point. Measures of the following will be included:

Maternal anxiety, using the GAD-7 [38], a 7-item scale measuring symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder. The GAD-7 has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .92) and good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.83) [38]. When used in perinatal populations the GAD-7 has yielded a sensitivity of 61.3 % and specificity of 72.7 %, using a cut-off score of 13 [42]

Maternal mood, using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [43], a 10-item self-report scale used to assess antenatal and postnatal depression [43–45]. The EPDS has a high level of test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.92) [46]. In the second trimester of pregnancy the sensitivity of the EPDS is estimated to be 88 % and the specificity 91 %, when using a cut-off score of 9/10 [44]

Pregnancy-specific worries, using the 10-item pregnancy-related anxiety scale [47]. The pregnancy-related anxiety scale has acceptable internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .78) [47]

Couple relationship, using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) [48], a 32-item self-report measure of relationship adjustment. The DAS has been reported to have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .915) [49]

Birth outcomes, using an 8-item maternal self-report questionnaire, developed for this study

Mother-child relationship, using the 25-item Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) [50]. The PBQ has been demonstrated to have acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .76) [51]. For identification of any disorder of the mother-infant relationship the PBQ has yielded a specificity of 74 % and sensitivity of 84 % [52]

Infant temperament, using a modified version of the Infant Behaviour Questionnaire (IBQ) [53]. Each subscale of the IBQ has been reported to have acceptable or good internal reliability: activity level (α = .73), smiling and laughter (α = .85), fear (α = .80), distress to limitations (α = .84), soothability (α = .84), and duration of orienting (α = .72) [53]

Infant sleep, using the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire [54]. This questionnaire has good test-retest reliability; significant correlations are reported between the repeated sleep measures for daytime sleep duration (r = .89), settling time (r = .94), nocturnal sleep-onset time (r = .95), nocturnal sleep duration (r = .82), number of night wakings (r = .88), and duration of nocturnal wakefulness (r = .95) [54]

Health-related quality of life of the mother, using the EuroQol-5D-3 L measure [55] recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for inclusion in economic evaluations

Health economics: the economic component of the proposed work will involve use of the Adult Service Use Schedule (AD-SUS) [56], a questionnaire designed for application to mental health populations, including depression and anxiety

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis

Data analysis will be primarily descriptive to aid the planning of a future RCT. Participant flow through the study will be presented following CONSORT guidelines [36]. Descriptive data will be presented in the form of means and standard deviations; medians and ranges; or percentages with 95 % confidence intervals, as appropriate depending on the data being described. The following will be calculated: (1) percentage of participants meeting eligibility criteria, (2) percentage of individuals consenting to the study, (3) percentage entering the randomisation phase, (4) the number of sessions completed by those in the treatment arm, (5) percentage completing the outcome measures at post-treatment follow-up, (6) between group pre-post effect sizes and confidence intervals on the GAD-7 and EPDS.

Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative interviews following the treatment groups will be transcribed verbatim. Transcripts will be analysed in detail using thematic analysis [57], informed by grounded theory methods. Atlas® software will be used to assist in organising content related to themes.

Data management

Data will be stored in line with NHS ethical procedures and a standard protocol is in place to outline data storage and security procedures. Participants’ questionnaires will be coded with a numerical identifier and kept separately from any identifiable personal information such as names or addresses. Data quality will be checked using double data entry for 10 % of the data and standard data management protocols will be followed.

Safety monitoring and reporting

A standard protocol is in place to deal with situations in which a participant reports risk to themselves or others. This protocol outlines the response of the researcher and necessary steps to take in order to ensure safety of the participant and others and to establish contact with caregivers or emergency support. If there are concerns about a child’s safety, a standard protocol for dealing with child protection issues will be followed. All risk or safety issues will be reported to the principal investigator, who will take any necessary further steps and provide on-going clinical supervision to members of the research team. The same protocol will be followed should participants disclose any information which is concerning to the research team, or if they score highly (at risk) on the questionnaire assessing mood (EPDS) (Additional file 2).

Debriefing sessions and clinical supervision with the individuals delivering the intervention will take place regularly.

If a participant’s condition should worsen or a co-morbid condition become apparent during the course of the trial the study team would refer the participant to existing healthcare services for additional treatment. In line with ethical guidelines, participants will be informed that should they wish to discontinue with the intervention they can withdraw at any point. If further care for any participant is needed post trial, the study team will refer the participant to existing healthcare services.

Any serious adverse events will be recorded and reported to the sponsor, the hosting NHS trust and to the ethics committee as appropriate.

Ethical approval

The trial received ethical approval from the London – Riverside National Research Ethics Service on 15 April 2014 (Research Ethics Committee reference number: 14/LO/0339). The trial will be conducted in accordance with the Data Protection Act at all times. The participants will be identified by a study specific participant number in all databases. Names and any other identifying detail will not be included in any study data electronic file. Where sample sizes are very small extra care will be taken to ensure that individual participants cannot be identified from the research data.

Dissemination

A range of dissemination strategies will be used:

A summary report and presentations on study findings will be prepared for clinical services, particularly primary care GP surgeries and maternity services. A presentation of findings will also be planned for clinical conferences and the annual Clinical Research Network conference

The trial team will present findings at relevant national and international conferences, and will submit papers on the feasibility RCT results and acceptability interviews to peer-reviewed journals. A full study report will be submitted to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)

The Patient and Public Involvement advisory group will advise and support on dissemination to service users. This will be achieved through our existing networks, which include close collaborations with national parenting websites, and through further contacts developed with this project

Newsletters and a summary of results will be prepared for stakeholder organisations, including those on the trial advisory group. Media releases and talks to non-specialist audiences will also be planned

Regular newsletters and a final summary report of trial findings will be sent to all study participants

Discussion

This two-phase feasibility study is designed to assess questions of feasibility and acceptability, in order to inform the design of a potential future substantive RCT. Detailed acceptability feedback will inform the further development of the intervention.

This group intervention led by midwives has the potential to be an acceptable, effective and cost-effective intervention for anxiety and stress during pregnancy. If effective it could improve short- and long-term outcomes for both mother and child, and reduce the overall population burden of anxiety during pregnancy. It is designed to fit alongside existing antenatal services and could, therefore, potentially be rolled out widely across the NHS.

Trial status

Recruitment is ongoing, and began in November 2014.

Acknowledgements

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-1112-29054). This study is sponsored by Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust (www.cnwl.nhs.uk). The sponsor and funding body did not have any role in the design of the study, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and will not contribute to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The study is being supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for North West London.

The authors would also like to thank the Mental Health Clinical Research Network for all their support with recruitment, providing clinical support officers when necessary.

Abbreviations

- AD-SUS

Adult Service Use Schedule

- CBT

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- DAS

Dyadic Adjustment Scale

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- GAD-7

Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

- GP

general practitioner

- IAPT

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies

- IBQ

Infant Behaviour Questionnaire

- NHS

National Health Service

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- PBQ

Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire

- RCT

randomised controlled trial

Additional files

SPIRIT Checklist. (PDF 130 kb)

Standard Operating Procedure where participant has elevanted levels of depressive symptoms. (PDF 386 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PGR is the chief investigator on the ACORN trial. PGR, EW, HO’M, PF, SH, GG, JD-B, JE and JM contributed to the grant application and designed the trial. HO’M led on the development of the intervention manual with DK, EW, PGR, PF, SH, JE, JM and JD-B. GG will oversee the development and implementation of the qualitative element. EW drafted the first draft of the manuscript, DK subsequent drafts, and all authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript prior to submission and approved the submitted draft.

Contributor Information

Esther L. Wilkinson, Email: esther.wilkinson@kcl.ac.uk

Heather A. O’Mahen, Email: H.O'Mahen@exeter.ac.uk

Pasco Fearon, Email: p.fearon@ucl.ac.uk.

Sarah Halligan, Email: s.l.halligan@bath.ac.uk.

Dorothy X. King, Email: dorothy.king@imperial.ac.uk

Geva Greenfield, Email: g.greenfield@imperial.ac.uk.

Jacqueline Dunkley-Bent, Email: jacqueline.dunkley-bent@nhs.net.

Jennifer Ericksen, Email: jennifer.ericksen@austin.org.au.

Jeannette Milgrom, Email: jeannette.milgrom@austin.org.au.

Paul G. Ramchandani, Email: p.ramchandani@imperial.ac.uk

References

- 1.Lee AM, Lam SK, Sze Mun Lau SM, Chong CS, Chui HW, Fong DY. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1102–12. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287065.59491.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Wulff M, Bondestam K, Åström M. Point prevalence of psychiatric disorders during the second trimester of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):148–54. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman JH, Chenausky KL, Freeman MP. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):E1153–84. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper PJ, Murray L, Hooper R, West A. The development and validation of a predictive index for postpartum depression. Psychol Med. 1996;26(3):627–34. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700035698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(3-4):245–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glover V, O’Connor TG. Effects of antenatal stress and anxiety: implications for development and psychiatry. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2002;180:389–91. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(1):14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis EP, Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Hobel C, Chicz-Demet A, Sandman CA. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression and cortisol influences infant temperament. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):737–46. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318047b775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field T, Diego M, Dieter J, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, et al. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and the newborn. Infant Behavior and Development. 2004;27(2):216–29. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor TG, Caprariello P, Blackmore ER, Gregory AM, Glover V, Fleming P. Prenatal mood disturbance predicts sleep problems in infancy and toddlerhood. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(7):451–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergman K, Sarkar P, O’Connor TG, Modi N, Glover V. Maternal stress during pregnancy predicts cognitive ability and fearfulness in infancy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1454–63. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31814a62f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance: Guideline CG192. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg192. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 15.Akkerman DCL, Croft G, Eskuchen K, Heim C, Levine A, Setterlund L, et al. Health care guideline: routine prenatal care. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. 2012. https://www.icsi.org/_asset/13n9y4/Prenatal.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 16.Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, Oberlander TF, Dell DL, Stotland N, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Colombia Reproductive Mental Health Program & Perinatal Services British Colombia. Best practice guidelines for mental health disorders in the perinatal period. 2014. http://reproductivementalhealth.ca/resources/best-practice-guidelines-mental-health-perinatal-period. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 18.BeyondBlue. Clinical practice guidelines for depression and related disorders – anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis – in the perinatal period. A guideline for primary care health professionals. Beyondblue: the national depression initiative. 2011. http://resources.beyondblue.org.au/prism/file?token=BL/0891. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 19.Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Clinical practice guidelines: antenatal care – module 1. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 2012. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/clinical-practice-guidelines-ac-mod1. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 20.Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Clinical practice guidelines: antenatal care – module II. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 2014. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/phd-antenatal-care-index. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 21.O’Mahen H, Fedock G, Henshaw E, Himle JA, Forman J, Flynn HA. Modifying CBT for perinatal depression: what do women want?: a qualitative study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19(2):359–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henshaw EJ, Flynn HA, Himle JA, O’Mahen HA, Forman J, Fedock G. Patient preferences for clinician interactional style in treatment of perinatal depression. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(7):936–51. doi: 10.1177/1049732311403499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reck C, Zimmer K, Dubber S, Zipser B, Schlehe B, Gawlik S. The influence of general anxiety and childbirth-specific anxiety on birth outcome. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(5):363–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunot V, Churchill R, Silva de Lima M, Teixeira V. Psychological therapies for generalised anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007;1:CD001848. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001848.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2):169–83. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemon EL, Vanderkruik R, Dimidjian S. Treatment of anxiety during pregnancy: room to grow. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(3):569–70. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milgrom J, Schembri C, Ericksen J, Ross J, Gemmill AW. Towards parenthood: an antenatal intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and parenting difficulties. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(3):385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panter-Brick C, Burgess A, Eggerman M, McAllister F, Pruett K, Leckman JF. Practitioner review: engaging fathers – recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(11):1187–212. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–85. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stapleton LR, Schetter CD, Westling E, Rini C, Glynn LM, Hobel CJ, et al. Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43) 2012;26(3):453–63. doi: 10.1037/a0028332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health. Maternity standard, national service framework for children, Young People and Maternity Services. Department of Health. 2004. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/199957/National_Service_Framework_for_Children_Young_People_and_Maternity_Services_-_Maternity_Services.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 33.The Royal College of Midwives. Reaching out: involving fathers in maternity care. The Royal College of Midwives. 2011. https://www.rcm.org.uk/sites/default/files/Father%27s%20Guides%20A4_3_0.pdf. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 34.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. Medical Research Council. www.mrc.ac.uk/complexinterventionsguidance. Accessed 12 Mar 2016.

- 36.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, Lancaster GA. What is a pilot or feasibility study?A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat Med. 1995;14(17):1933–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):307–12. doi: 10.1111/j..2002.384.doc.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simpson W, Glazer M, Michalski N, Steiner M, Frey BN. Comparative efficacy of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as screening tools for generalized anxiety disorder in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Can. J Psychiatr. Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2014;59(8):434–40. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal Of Psychiatry: the Journal Of Mental Science. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray D, Cox JL. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS) Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1990;8(2):99–107. doi: 10.1080/02646839008403615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kernot J, Olds T, Lewis LK, Maher C. Test-retest reliability of the English version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18(2):255–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 1999;18(4):333–45. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham JM, Liu YJ, Jeziorski JL. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale: a reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(3):701–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brockington IF, Oates J, George S, Turner D, Vostanis P, Sullivan M, et al. A screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2001;3(4):133–40. doi: 10.1007/s007370170010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wittkowski A, Wieck A, Mann S. An evaluation of two bonding questionnaires: a comparison of the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale with the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire in a sample of primiparous mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(4):171–5. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0191-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brockington IF, Fraser C, Wilson D. The Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire: a validation. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):233–42. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rothbart MK. Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Dev. 1981;52(2):569–78. doi: 10.2307/1129176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):E570–E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.EuroQol Group EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byford S, McCrone P, Barrett B. Developments in the quantity and quality of economic evaluations in mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2003;16(6):703–7. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200311000-00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]