Abstract

Objective. Sweat collected for testing should have quantity not sufficient (QNS) rate of ≤10% in babies ≤3 months of age. Michigan (MI) cystic fibrosis (CF) centers’ QNS rates were 12% to 25% in 2009. This project was initiated to reduce sweat QNS rates in MI. Methods/Steps. (a) Each center’s sweat testing procedures were reviewed by a consultant. (b) Each center received a report with recommendations to improve QNS rates. (c) Technicians visited other participating centers to observe their procedures. Results. A total of 778 infants were identified as positive via CF newborn screening over a 2-year period. The mean age at time of sweat test was 23.2 days (SD ± 13.0 days). The overall QNS percent decreased from 14.4% to 9.5% (P = .04) during the study. Conclusion. This project and teamwork approach led to a decrease of sweat test QNS rates, opportunities to solve a common problem, and improved quality of care.

Keywords: pulmonology, general pediatrics, genetics, neonatology, infectious diseases

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is one of the most common life-threatening inherited diseases with a prevalence of about 1 in 3500 live births.1 Newborn screening (NBS) for CF has now been implemented in all the states in the United States and in many countries worldwide. Infants as young as 1 week of age with positive NBS for CF are routinely referred to accredited CF centers for sweat testing to confirm the diagnosis.2,3 Sweat collection requires sweat gland stimulation with pilocarpine iontophoresis and collection of sweat via Gibson and Cook technique (GCT) or Macroduct Sweat Collection System (MSCS; Wescor, Logan, UT).2,4 For adequate sweat samples, the collected sweat must be ≥75 mg (via GCT) or ≥15 µL (via MSCS).2 Lower weights or volumes of sweat specimens cannot be analyzed and are labeled as “quantity not sufficient” (QNS).3,4 One recent study compared the performance of the MSCS to the GCT in determining the sweat testing QNS rate in infants with a positive CF NBS over a period of 4 years in Minnesota.5 This report found a higher QNS rate using the GCT compared to the MSCS (15.4% vs 2.1% respectively).5

Younger infants are more likely to produce a higher QNS rate than older children.6,7 Accordingly, infants with QNS samples need repeat testing, which leads to increased time to diagnosis, additional stress to the infants and their families, and an extra cost for testing.8 Currently, the cost of sweat testing is approximately $500 per test. The CF Foundation has placed a great importance on minimizing QNS rates and established several guidelines to standardize performance of sweat testing. The recommended QNS rate for children older than 3 months of age is ≤5%.2,3 Since younger infants are being increasingly referred for sweat testing via the CF NBS programs, the CF Foundation added a standard stipulation of QNS rate ≤10% for patients ≤3 months of age,3,4 a goal many centers struggle to meet.

In Michigan, NBS for CF began in October 2007 using an immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT)/DNA algorithm. Blood spots from infants having an IRT concentration ≥96th percentile undergo further analysis with a panel of 40 CF gene mutations. Infants with one or more DNA mutations are referred to 1 of 5 CF Foundation–accredited care centers in Michigan for confirmatory sweat testing. Three hundred and fifteen infants born in 2008 underwent sweat testing at a mean age of 26 days.9 Of the 315 infants, 63 (20%) had QNS results, with the center-specific rates ranging from 12% to 30%.9 A literature search comparing the QNS rates in Michigan to the QNS rates of other state NBS programs revealed only 2 studies that listed QNS rates from a population of infants in the United States referred for confirmatory sweat testing following a positive newborn screen.3,7 Massachusetts reported the QNS rate ranged from 3% to 17% for sweat tests conducted during the first 8 weeks of life.7 Illinois had a QNS rate of 10% with a median age at sweat test of 22 days for those with sufficient tests and 17 days for those with insufficient tests.3 LeGrys et al reported summary QNS rates for infants ≤3 months of age of 7% from a national survey of CF care centers and 8% from a survey of state leaders involved in NBS, though the site-specific QNS rates displayed wide variability.3

Many reports have examined the association between specific characteristics and QNS results focusing either on a single infant characteristic or a combination of infant factors.6,7,9-13 We previously conducted a study using a population-based cohort of all infants identified by NBS in Michigan and referred for confirmatory sweat testing to evaluate predictors of QNS rate and to devise a quality improvement (QI) strategy to reduce the QNS rate in neonates during confirmatory testing in order to meet the CF Foundation guidelines.9 The study found that corrected age at the time of sweat test, defined by summing gestational age and postdelivery age at the time of test, should be considered when determining the appropriate time to perform a sweat test. As a result of this study, Michigan’s NBS Program adjusted its CF algorithm to wait until infants screening positive for CF reach 39 weeks of corrected age prior to sweat testing in order to reduce the QNS rate.9

Our current QI study looked at different ways to reduce sweat testing QNS rate among infants ≤3 months of age. To our knowledge, this is the first population-based cohort study to evaluate sweat testing QNS rates before and after implementation of several recommendations for improvement.

Materials and Methods

Study Description

This population-based cohort study evaluated insufficient collected sweat samples in infants ≤3 months of age during NBS confirmatory testing for CF before and after implementing QI strategies. Four CF Foundation accredited care centers in Michigan participated directly in this QI study (Centers A-D). Each of the 4 participating CF centers reviewed its QNS rate and the sweat testing procedure as outlined by the CF Foundation Guidelines. CF care centers in Michigan employ 2 different methods of sweat testing. One center uses GCT, whereas 3 centers use the MSCS. Both methods were equally recommended for appropriate collection of sweat samples from subjects of all age groups including newborns.2 A clinical laboratory consultant with expertise in sweat testing was invited to visit each center. The expert reviewed the sweat test procedure at each center and provided suggestions for improvement on techniques, methods of collection, and analysis of the collected sweat samples. A list of best practice recommendations from the expert was provided to the participating CF Care Centers to improve the sweat testing techniques. The steps that were implemented by each center were noted, as well as the date implemented. Information from site visits at all 4 centers was collected, and helpful steps in lowering QNS rates shared.

Centers Quality Improvement Process

In addition to the steps taken by all centers for this QI project, each center implemented additional measures when warranted based on individual needs. Center A had 2 site visits; one visit was prior to the start of the project and one was part of the project.

Study Population

The study population was restricted to newborns and infants who received a sweat test at 1 of the 4 participating CF Foundation–accredited care centers following a positive newborn screen for CF in Michigan. The population was further restricted to infants with a sweat test performed in the 18 months before and after the site visit by the clinical laboratory consultant. Three of the 4 centers (B-D) had a site visit in October 2011, so newborns who received a sweat test from May 2010 through April 2013 were included. The other center (A) had a site visit in December 2011, so newborns who received a sweat test from July 2010 through June 2013 were included. Last, only infants who received an initial sweat test ≤3 months of age were included.

Processing and Data Storage

Initial NBS data, including the demographic and perinatal characteristics and IRT concentrations, are stored in a Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) created by Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Inc. Confirmatory testing and medical management data are stored in a database managed by the NBS Follow-up Program. To characterize the population undergoing sweat testing, the following variables collected on the NBS filter paper were used in this study: birth weight, gestational age, race, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission following birth. In addition, medical management data including CF care center, sweat test results, and age at time of sweat test were also used. Gestational age was dichotomized as <39 weeks and ≥39 weeks. Birth weight was also dichotomized into <2000 g or ≥2000 g. The 6-level race variable collected on the NBS filter paper was collapsed into white, black, and other. Age at time of sweat test was determined using the date of sweat test and birth date. The 2 sweat test result options were QNS or non-QNS.

Sweat Collection

All centers’ sweat testing laboratories follow the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines and are accredited by the CF Foundation. Centers A, C, and D used the Wescor Macroduct Sweat Collection System (Model 3700 SYS), and Center B used the Gibson–Cooke Sweat Test Apparatus (model IPS-25). Using the Macroduct system, CAP-certified technicians cleaned the area to be tested with water, inserted a new pilogel disc at each electrode, secured electrodes to the newborn’s limb, and applied 1.5 A of current for 5 minutes. After removing the electrodes, the Macroduct sweat collection coil was secured to the area of the positive electrode for 30 minutes. If the sweat retention capacity of the coils was exceeded before 30 minutes, collection was stopped when the coils were full. When a patient did not produce a sweat sample of 15 µL, the attempt was counted as QNS. When using the Gibson–Cooke Apparatus, 2 electrodes were each covered by a 2 × 2 inch gauze pad soaked in 2 to 3 mL of 0.4% pilocarpine nitrate at the positive electrode, and a current of 2 to 3 mA was applied for 5 minutes. The area was cleaned and sweat was collected for 30 minutes on a 2 × 2 inch gauze pad wrapped in evaporation-resistant film (Coban) over the area of the positive electrode. If the sample taken from the patient weighed less than 75 mg during that session, the attempt was counted as QNS.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Chi-square tests were used to determine the bivariate associations with sweat test outcome (QNS v. non-QNS) and the following variables: birth weight, gestational age, race, NICU admission, and CF care center. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to determine the associations between sweat test outcome in the 18-month periods before and after the site visit for all CF care centers combined and by center for all sweat tests performed and then separately by NICU status. To allow for time for the recommended changes to be implemented, QNS rates were determined for 2 time periods: 6 months after the visit and the subsequent 12 months. The average age at time of sweat test overall and by NICU status were calculated for each center, and t-tests were used to test for significant differences in the 18-month period following the site visit compared to the 18-month period before the visit. An α value of .05 was used for this study.

Results

Overall, 778 infants were identified as screen positive for CF through the NBS Program and underwent sweat testing at the 4 participating Michigan CF care centers during the 18-month periods before and after the site visit (Table 1). Thirty-six infants received their initial sweat test >3 months of age and were excluded, leaving a final study population of 742 infants. The mean age at time of sweat test was 23.2 days (SD +13.0) and median of 20 days.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Infants With a Sweat Test, Overall and by Sweat Test Result, 18-Month Period Before and After Site Visita.

| Characteristic | Overall | Initial Sweat Test Result |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QNS |

Not QNS |

P Value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Race | |||||||

| White | 571 | 80.9 | 71 | 12.4 | 500 | 87.6 | .83 |

| Black | 93 | 13.2 | 10 | 10.8 | 83 | 89.2 | |

| Other | 42 | 5.9 | 6 | 14.3 | 36 | 85.7 | |

| Gestational age | |||||||

| <39 weeks | 218 | 30.5 | 44 | 20.2 | 174 | 79.8 | <.001 |

| ≥39 weeks | 497 | 69.5 | 43 | 8.7 | 454 | 91.3 | |

| Birth weight | |||||||

| <2000 g | 10 | 1.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 6 | 60.0 | .005 |

| ≥2000 g | 723 | 98.6 | 81 | 11.2 | 642 | 88.8 | |

| NICU admission | |||||||

| Yes | 87 | 11.7 | 19 | 21.8 | 68 | 78.2 | .002 |

| No | 655 | 88.3 | 69 | 10.5 | 586 | 89.5 | |

| CF Care Center | |||||||

| A | 258 | 34.8 | 18 | 7.0 | 240 | 93.0 | .001 |

| B | 65 | 8.8 | 4 | 6.2 | 61 | 93.8 | |

| C | 226 | 30.5 | 30 | 13.3 | 196 | 86.7 | |

| D | 193 | 26.0 | 36 | 18.7 | 157 | 81.3 | |

| Total | 742 | 100.0 | 88 | 11.9 | 654 | 88.1 | |

Abbreviations: QNS, quantity not sufficient; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; CF, cystic fibrosis.

Missing data are as follows: race (n = 36), gestational age (n = 27), birth weight (n = 9).

P value is significant if < .05.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics for all patients who received a sweat test in the 18 months before and after the site visit at each of the centers. The QNS percent significantly differed by gestational age, birth weight, NICU admission, and CF Care Center, but did not significantly differ by race. The QNS percent was approximately 2 to 4 times greater among those who were <39 weeks or <2000 g compared to their counterparts. Those admitted to the NICU were approximately twice as likely to experience a QNS result compared to those not admitted to the NICU (22% QNS compared to 10.5%).

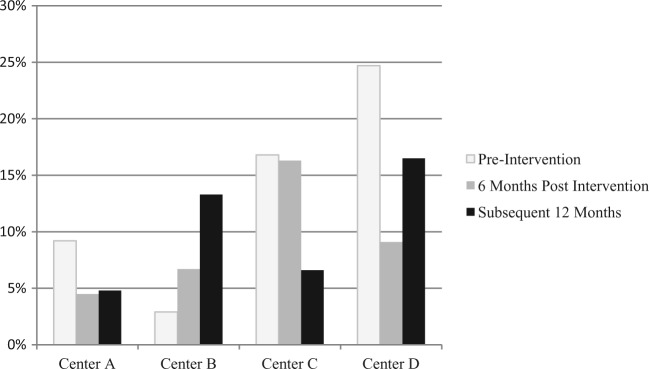

The QNS rate was assessed 6 months following the expert’s intervention and compared to the subsequent 12 months (Figure 1). Two centers (B and D) had a lower QNS rate 6 months postintervention (6.7% and 9.1%) when compared to the QNS rate after another 12 months had passed (13.3% and 16.5%), one center (A) had an essential equivalent QNS rate 6 months postintervention (4.5%) compared to the rate after another 12 months (4.8%), and the remaining center (C) had a higher QNS rate 6 months postintervention (16.3%) when compared to the rate after another 12 months (6.6%).

Figure 1.

QNS rates by center 6 months after expert intervention compared to the following 12 months.

The months following implementation were condensed and reported as an 18-month period for statistical efficiency. Overall, the QNS percent decreased at 3 of the 4 centers in the 18-month period following the site visit compared to the 18-month period before the site visit, though none of the center-specific decreases reached statistical significance (Table 2). One center experienced an increase in the QNS percent driven by 3 infants with a QNS following the site visit compared to 1 infant with a QNS prior to the site visit. For all 4 centers combined, the QNS percent decreased from 14.4% to 9.4%, and the decrease achieved statistical significance (P = .04).

Table 2.

QNS Percent in 18 Months Before and After Site Visit, Overall and by NICU Status.

| Center | Overall |

NICU |

Non-NICU |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After |

P Value | Before |

After |

P Value | Before |

After |

P Value | |||||||||||||

| Sweat | Sweat | Sweat | Sweat | Sweat | Sweat | ||||||||||||||||

| Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | Tests (n) | QNS (n) | QNS (%) | ||||

| A | 130 | 12 | 9.2 | 128 | 6 | 4.7 | .15 | 16 | 2 | 12.5 | 16 | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 114 | 10 | 8.8 | 112 | 4 | 3.6 | .10 |

| B | 35 | 1 | 2.9 | 30 | 3 | 10.0 | .21 | 2 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | .67 | 33 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 3 | 10.3 | .10 |

| C | 107 | 18 | 16.8 | 119 | 12 | 10.1 | .14 | 21 | 5 | 23.8 | 10 | 1 | 10.0 | .28 | 86 | 13 | 15.1 | 109 | 11 | 10.1 | .29 |

| D | 81 | 20 | 24.7 | 112 | 16 | 14.3 | .07 | 9 | 5 | 55.6 | 12 | 3 | 25.0 | .14 | 72 | 15 | 20.8 | 100 | 13 | 13.0 | .17 |

| Total | 353 | 51 | 14.4 | 389 | 37 | 9.5 | .04 | 48 | 13 | 27.1 | 39 | 6 | 15.4 | .19 | 305 | 38 | 12.5 | 350 | 31 | 8.9 | .13 |

Abbreviations: QNS, quantity not sufficient; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

P value is significant if < .05.

When stratifying by NICU admission, the QNS percent among all 4 centers combined decreased from 27.1% to 15.4% for infants admitted to the NICU and from 12.5% to 8.9% for infants not admitted to the NICU, though neither decrease was statistically significant (Table 2). Three of the 4 centers had fewer QNS results among NICU infants following the site visit and the fourth center remained the same. For non-NICU infants, 3 of the 4 centers had reduced QNS percentages in the 18-month period after the site visit compared to the 18 months before the visit.

The average age at time of sweat test increased among NICU and non-NICU infants in the 18 months following the site visit (Table 3), though the increases were not statistically significant, except for Center D with an average age of 16.7 days to 22.6 days. The average age at time of sweat test increased approximately 6 days overall and 19.5 days among NICU infants in the 18-month period after the site visit at Center D compared to the 18-month period before the visit.

Table 3.

Average Age at Time of Sweat Test (Days) in 18 Months Before and After Site Visit, Overall, by CF Care Center, and NICU Status, Michigan.

| Overall |

NICU |

Non-NICU |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | Before | After | P Value | Before | After | P Value | Before | After | P Value |

| A | 26.5 | 26.0 | .76 | 36.6 | 29.6 | .25 | 25.1 | 25.5 | .83 |

| B | 22.5 | 23.0 | .86 | 11.0 | 15.0 | .58 | 23.2 | 23.2 | .98 |

| C | 22.9 | 22.1 | .66 | 35.9 | 31.0 | .58 | 19.7 | 21.3 | .28 |

| D | 16.7 | 22.6 | .002 | 24.3 | 43.8 | .01 | 15.7 | 20.0 | .001 |

| Total | 22.8 | 23.6 | .39 | 32.9 | 34.0 | .80 | 21.2 | 22.4 | .15 |

Abbreviations: NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; CF, cystic fibrosis.

P value is significant if < .05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter QI project aimed at lowering the sweat chloride QNS rate following a positive CF newborn screen for babies ≤3 months of age. Michigan’s multicenter participation provided the opportunity to assess a greater population and more diverse set of protocols. The overall QNS rate was significantly reduced from 14.4% in the 18 months prior to the site visits by a clinical laboratory expert to 9.5% in the 18 months following the visits. Reducing the QNS sweat testing rate is important not only to adhere to the CF Foundation guidelines3,4 but also to expedite completion of the screening process, thereby reducing associated parental anxiety and confusion regarding results.14 It also allows starting treatment for babies with CF as early as possible. This project permitted a systematic assessment of each center’s sweat testing process followed by training of personnel and implementation of strategies to improve patient’s preparation, sweat collection, and analysis process.

In our study, all but one CF center joined together in a transparent fashion to work on a common problem. This collaborative effort was possible due to willing collaboration that led to strengthening relationships between centers and their personnel through the benchmark intercenter site visits. Consistent with prior work by LeGrys, which revealed a very wide range of QNS rate of 0% to 40% in infants <3 months of age referred after NBS,3 our site-specific QNS rates ranged from 2.9% to 24.7% in the 18 months prior to the site visits. In this study, there was significant reduction of QNS rate in Michigan following implementation of the project. Although overall, each center lowered its QNS rate, not all center-specific rates were below the CF Foundation recommended rate of 10% or lower, indicating the need for continuous improvement efforts. After the end of the project, only center D’s QNS rate remained higher than the recommended QNS rate, but this center has made considerable improvement from its initial QNS rate of 24.7% at the beginning of the study.

Three of the 4 centers did not include analysis of QNS rate by technician performing the test similar to Boas et al.15 However, we were able to identify common problems between centers, which were addressed through conference calls and site visits. The sweat testing procedure was reviewed at every visit and necessary changes were implemented. For center B, review of the sweat testing process was done with the laboratory personnel and procedural changes were made accordingly. In addition, parents were contacted prior to testing to ensure babies are well hydrated prior to testing. Center C tracked the individual technician’s performance in the collection and analysis of the sweat testing samples. QNS rate per technician was reviewed weekly and any deficiencies in training were addressed. Also, parents were contacted prior to testing to ensure babies were well hydrated prior to testing. Center D established monthly meetings between the laboratory staff and the CF team members to improve communication and address any deficiencies. One center (center C) did internal analysis of QNS rate by technician. Weekly review of the data to address any deficiency identified was done. In addition, specific problems within each center were identified and addressed at the center level.

The second step in our QI project provided a unique opportunity for direct observation, discourse, and education among center personnel directly involved in sweat test procedures. All participating center personnel provided positive commentary on the value of this second step, in particular, the opportunity to witness first-hand the process in different centers and gain insight on approaches that may be adapted or refined in their own centers. We believe this collaborative interaction was instrumental in reducing the QNS rate.

Our data suggest the need for continued collaboration and monitoring, in particular, when one compares the QNS rate 6 months postintervention with the subsequent 12 months. We initially assessed this difference to determine if there was a lag in QNS improvement to allow for staff training and implementation of recommendations. This was apparent with one center, but we noted in 2 centers the QNS rate was better at 6 months postintervention when compared to the subsequent 12 months. This may reflect a greater emphasis on recommendations for improvement that waned over time with regression back to prior standards/practice; thus, continued discussion among CF Center staff and review of recommendations for improvement may be needed.

NICU infants were assessed independently from non-NICU infants because of their underlying medical condition or prematurity requiring NICU admission, potentially confounding the increased rate of QNS. In the past, it was noted that NICU infants with ultrahigh IRT and no mutations did not have a final diagnosis of CF. After our analysis in 2009, Michigan babies with ultrahigh IRT and no mutations were not considered screen positive for CF.16 Ultrahigh IRT infants were not included in this cohort; thus, they did not affect our results.

This project was challenging because it included several centers with different problems/issues in relation to the sweat testing process. Another challenge was organizing the site visits between centers. A third challenge was the data collection and sharing of the QI steps in each center. These challenges required a significant degree of collaboration and transparency between centers. Center C played a leading role in organizing the technicians’ visits to all the participating centers, which took several months to accomplish. In addition, 2 medical students at center C assisted in data collection and documentation of changes made by participating centers and information exchanged between all the technicians who took part in the project.

In conclusion, this QI project led to collaboration and coordination between the CF centers in Michigan and resulted in the reduction of the overall QNS rate for all participating centers. We believe this will positively affect the parental experience by reducing their anxiety and confusion over the testing process, which is the ultimate indicator of success. The multicenter collaboration is continuing today and leading to other QI projects between centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Vicky LeGrys for her help as a consultant and her valuable feedback to all the cystic fibrosis centers. We thank Sarah Chaudhry, one of the medical students who worked on data collection. We also thank all the therapists and the laboratory technicians who took part in the study and performed the collection and analysis of sweat tests in all the participating cystic fibrosis centers.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This study was presented in part at the 27th Annual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference, Salt Lake City, UT, 2013, and the European Cystic Fibrosis Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, June 11-14, 2014.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation in the United States.

References

- 1. Sontag MK, Hammond KB, Zielenski J, Wagener JS, Accurso FJ. Two-tiered immunoreactive trypsinogen-based newborn screening for cystic fibrosis in Colorado: screening efficacy and diagnostic outcomes. J Pediatr. 2005;147:S83-S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Legrys VA, McColley SA, Li Z, Farrell PM. The need for quality improvement in sweat testing infants after newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2010;157:1035-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. LeGrys VA, Yankaskas JR, Quittell LM, Marshall BC, Mogayzel PJ., Jr. Diagnostic sweat testing: the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines. J Pediatr. 2007;151:85-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laguna TA, Lin N, Wang Q, Holme B, McNamara J, Regelmann WE. Comparison of quantitative sweat chloride methods after positive newborn screen for cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:736-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eng W, LeGrys VA, Schechter MS, Laughon MM, Barker PM. Sweat-testing in preterm and full-term infants less than 6 weeks of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Sweat testing infants detected by cystic fibrosis newborn screening. J Pediatr. 2005;147:S69-S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee DS, Rosenberg MA, Peterson A, et al. Analysis of the costs of diagnosing cystic fibrosis with a newborn screening program. J Pediatr. 2003;142:617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kleyn M, Korzeniewski S, Grigorescu V, et al. Predictors of insufficient sweat production during confirmatory testing for cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farrell PM, Koscik RE. Sweat chloride concentrations in infants homozygous or heterozygous for F508 cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:524-528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harpin VA, Rutter N. Sweating in preterm babies. J Pediatr. 1982;100:614-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LeGrys VA. Sweat testing for cystic fibrosis: profiles of patients with insufficient samples. Clin Lab Sci. 1993;6:73-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taccetti G, Festini F, Braccini G, Campana S, de Martino M. Sweat testing in newborns positive to neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F463-F464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang CW, McColley SA, Lester LA, Ross LF. Parental understanding of newborn screening for cystic fibrosis after a negative sweat-test. Pediatrics. 2011;127:276-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boas SR, Hageman J, Washburn J, Piasecki S, Liveris M. Results of a quality improvement program for sweat testing to diagnose cystic fibrosis. Lab Med. 2012;43:12-14. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Korzeniewski SJ, Young WI, Hawkins HC, et al. Variation in immunoreactive trypsinogen concentrations among Michigan newborns and implications for cystic fibrosis newborn screening. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:125-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]