Abstract

The sodium hydrogen exchanger isoform one (NHE1) plays a critical role coordinating asymmetric events at the leading edge of migrating cells and is regulated by a number of phosphorylation events influencing both the ion transport and cytoskeletal anchoring required for directed migration. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) activation of RhoA kinase (Rock) and the Ras-ERK growth factor pathway induces cytoskeletal reorganization, activates NHE1 and induces an increase in cell motility. We report that both Rock I and II stoichiometrically phosphorylate NHE1 at threonine 653 in vitro using mass spectrometry and reconstituted kinase assays. In fibroblasts expressing NHE1 alanine mutants for either Rock (T653A) or ribosomal S6 kinase (Rsk; S703A) we show each site is partially responsible for the LPA-induced increase in transport activity while NHE1 phosphorylation by either Rock or Rsk at their respective site is sufficient for LPA stimulated stress fiber formation and migration. Furthermore, mutation of either T653 or S703 leads to a higher basal pH level and a significantly higher proliferation rate. Our results identify the direct phosphorylation of NHE1 by Rock and suggest that both RhoA and Ras pathways mediate NHE1-dependent ion transport and migration in fibroblasts.

Keywords: Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger, NHE1, Protein kinase, RhoA, Rock kinase, phosphorylation, Rsk, cytoskeleton, migration, lysophosphatidic acid, proton transporter

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

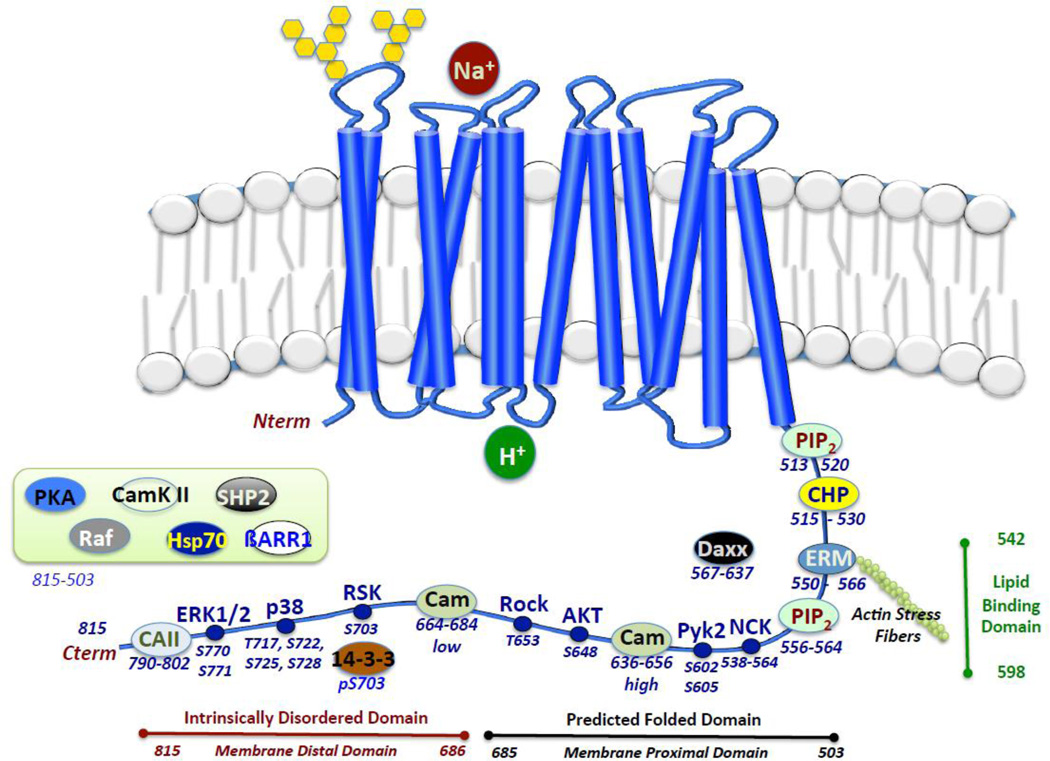

The sodium hydrogen exchanger isoform 1 (NHE1) is a ubiquitously expressed plasma membrane protein responsible for transport of an intracellular proton for an extracellular sodium in a one-to-one electroneutral exchange driven by the sodium gradient (1–11). The exchanger plays important cellular roles including, intracellular pH (pHi) homeostasis, cell migration coordination, cell volume control and anchoring protein interactions at the cell membrane. The exchanger consists of two functional domains: The ion transport domain, embedded within the plasma membrane which contains the proton sensor mechanism (residues 1–502) responsible for the pH set point, and the cytoplasmic domain consisting of an extended cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (residues 501–815) involved in regulation of ion transport and anchoring cytoplasmic proteins. The cytoplasmic domain interacts with a number of accessory proteins and lipids, and is phosphorylated by seven known kinases (1–3). The cytoplasmic domain can be divided into to two halves; the amino acids (503–685) proximal to the membrane are primarily helical, while the membrane distal domain 686 – 815, is intrinsically disordered (ID) (12). Both the proton-transport and proteinbinding functions of NHE1 are critical for directed cell motility in healthy cells. Deregulation of NHE1 leads to alterations in pHi, proliferation, cell volume control, apoptosis, invasion and metastasis and directed cell motility (8– 10).

Much of the critical activity of NHE1 is regulated by phosphorylation. There are fourteen identified phosphorylation events by seven different protein kinases (2, 3, 13). The specific amino acids phosphorylated by Nck-interacting kinase (NIK) and RhoA Kinase (Rock) have not been identified. Both ERK1/2 and ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) phosphorylate within the ID domain of NHE1, while several other NHE1 phospho-sites including the predicted Rock site, lie within the membrane proximal helical domain. How these phosphorylation events control NHE1 is not clear, however the impact of NHE1 phosphorylation by ERK 1/2 alters the structure of the cytoplasmic domain which may regulate transport function (3). The location and diversity of phosphorylation hints at the complexity of NHE1 regulation.

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signals through five known G protein-coupled receptors leading to the activation of diverse GPCR signaling pathways, cross-activation of Ras-ERK growth factor pathways, and regulation of the small G protein RhoA (14, 15). LPA signaling leads to stress fiber formation and cell motility through a mechanism that involves activation of NHE1. Stimulation of the RhoA effector Rock, by LPA directly phosphorylates the carboxylterminus of NHE1 at an un-identified amino acid, showing that RhoA and Rock are required for LPA-induced ion exchange, stress fiber formation and enhanced cell motility (16–19).

Rock plays a specific role in inducing and stabilizing stress fiber formation through myosin light chain and LIM kinases and is thought to function primarily at the tail of migrating cells (20). Both isoforms of Rock are conserved (64% amino acid homology) with a poorly defined consensus substrate sequence of R/KXS/T or R/KXXS/T where X is any amino acid (20, 21). Rock I and Rock II are expressed in most tissues with a slightly higher expression of Rock I in non-neuronal tissues and Rock II found in higher levels in brain and muscle tissue.

Rsk is a Ser/Thr kinase activated by ERK 1/2 with several known substrates. NHE1 was first identified as a Rsk substrate at S703 where the phosphorylation was responsible for serum- and thrombin-induced activation of the transporter (22–24). This phosphorylation site was later shown to be critical to recruit 14-3-3 interaction to NHE1 where binding enhanced proton transport (23). Additional evidence supporting Rsk regulation of NHE1 was identified in tumor cells under hypoxic conditions where Rsk mediates the NHE1-induced extracellular acidification of microdomains of invadipodia (25). Furthermore, Rsk-activation of NHE1 in part causes ischemic damage after reperfusion in both cerebral and cardiac tissue (26, 27).

Work in our laboratory found that LPA stimulated NHE1 through both ERK- and RhoA/Rock-dependent pathways (28). Pharmacological inhibitors for either pathway only partially blocked the stimulation of proton transport whereas complete inhibition of NHE1 transport was achieved with a combination of Rock and ERK inhibition (29). We also showed that inhibition of Rock-induced NHE1 activity abrogated the ability of LPA to stimulate stress fiber formation and fibroblast migration (23). This work suggests that Rsk and Rock collaborate through an undefined mechanism to coordinate LPA-induced NHE1 activity and function. Therefore dissecting the impact of these two phosphorylation sites on NHE1 could identify a role for both Rock and Rsk on NHE1 function. Therefore the aim of this work was to identify NHE1 as a bona fide Rock substrate and to evaluate the cellular impact of loss of this phosphorylation site on NHE1 activity and cellular function.

In this study, we used a reconstituted in vivo kinase assay and mass spectroscopy analysis, to demonstrate that both Rock I and II phosphorylate NHE1 at a specific, unique residue, threonine 653 (T653). To identify the role of this phosphorylation site in NHE1-regulated cellular functions we used three distinct cell lines: 1) PSN T653A which expresses a human NHE1 lacking the Rock phosphorylation site, 2) PSN S703A expressing human NHE1 lacking the Rsk phosphorylation site, and 3) PSN TSA expressing human NHE1 lacking both phosphorylation sites. Here we show that the LPA-induced increase in NHE1 transport activity requires both phosphorylation events while loss of either phosphorylation site nearly completely impairs stress fiber formation and cell migration. Finally, the loss of either phosphorylation site increases resting pHi and enhances cellular proliferation. These findings suggest that there is a distinct mechanism by which each of these two kinases impacts NHE1 ion transport but both are integral to NHE1-regulated cell migration events.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 ctNHE1 plasmid construction and recombinant protein purification

The carboxyl terminal cytoplasmic domain (amino acids 612–815) of Human NHE1 (ctNHE1), gene SLC9A1, NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_003038.2 was first analyzed for rare codons to optimize protein expression in E. coli. The optimized nucleotide sequence without altered amino acids including eight histidine residues on the amino terminus of the peptide was synthesized with Ncol (5’) and XhoI (3’) restriction sites and the insert subcloned into pET28a vector. Recombinant ctNHE1 protein was expressed in six-liter cultures of Rosetta gami (DH3 & pLyse) E. coli in the presence of 25 µg/ml kanamycin and 34 µg/ml chloramphenicol. Protein expression was initiated when cells reached an O.D. of 0.5 with 1.0 mM IPTG for 4 hours at 30°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed with BugBuster protein extraction reagent (EMD Millipore) with 0.001 mg DNaseA in 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM β mercaptoethanol, 5 mM PMSF, 0.08 µM Aprotinin, 0.5 µM bestatin, 0.2 µM leupeptin, 0.1 µM pepstatin A and 1 mM AEBSF-HCl (lysis buffer). After centrifugation to remove insoluble particles, the lysate was applied to a 30 ml Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen) and washed with five column volumes lysis buffer containing 0.5 mM NaCl. Non specific binding proteins were eluted with 10 column volumes of lysis buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl and 20 mM imidazole. Recombinant protein was eluted with 150 ml of lysis buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl and 300 mM imidazole. Fractions containing ctNHE were pooled, dialyzed against 50 column volumes of lysis buffer and concentrated by ultrafiltration using a YM10 centricon filtration device (EMD Millipore). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford dye binding and purity determined by SDS PAGE and coomasie staining. Typical yields ranged from 2 – 14 mg ctNHE1.

2.2 In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant ctNHE

Purified recombinant ctNHE1 (25 µg) or control peptide substrate R6 (S6K) was incubated with 0.5 µg of Rock isoform I or Rock isoform II (EMD Millipore) in 20 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 25 mM β glycerol phosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 4 mM MgCl2 and 100 µM ATP. Samples were incubated for 1 to 100 min and then the reaction was stopped by either snap freezing for mass spectrometry, adding SDS PAGE sample buffer for autoradiograph, or by loading on filter paper for quantitative radiolabel detection. Radiolabeling phosphorylation with 5 µCi of [γ–32P]ATP was performed by incubating samples for 30 min at 30°C, then transferring 25µl of each sample to phosphocellulose paper (P81, Whatman). The paper squares were washed in 75 mM phosphoric acid with three changes of solution and a final wash with acetone. The bound radiolabeled protein/peptide was quantified by scintillation counting.

2.3 Preparation of ctNHE peptides for mass spectrometry

Six µg (260 pmol) of the unphosphorylated or phosphorylated form of ctNHE was incubated in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.3 and 4 mM DTT in a final volume of 100 µL for 10 minutes at 50°C. Cysteine residues were alkylated by the addition of iodoacetamide to a final concentration of 14 mM and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. The reaction was quenched by adding DTT to a final concentration of 7.4 mM. Trypsin Gold (Promega) was added to a final concentration 1% w/w relative to ctNHE and the reaction was incubated 18 hr at 37°C. Peptides were desalted and concentrated by solid phase extraction using a 0.6 µL Zip-Tip (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instruction to yield a final volume of 5 µL in 75% ACN/0.1% TFA. Multiple aliquots (0.5 µL) were spotted on a MALDI plate with an equal volume of 20 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% ACN, 0.1% TFA.

2.4 Peptide mass spectrometry

The samples were analyzed in reflector mode with an AB 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass analyzer. Spectra of precursor ions were acquired in positive mode with a mass range of 900 to 4000 m/z and a focus mass of 2500. Shots per MS subspectrum were fifty with a total accumulation of 1000 shots per spectrum. Laser intensity range was 3282 to 4075. The 20 most intense ions were selected for MSMS with MSMS acquisition beginning with the weakest at a resolution of at 200 FWHM. Collision-induced dissociation was turned off and metastable suppressor turned on. Accumulations per MSMS subspectrum were 50 for a total of 3000 shots per spectrum. Spectra were searched against a small theoretical tryptic peptide database containing the ctNHE sequence using Mascot version 2.2 (Matrix Science). Carbamidomethylation was set as a constant modification and pyro-Glu (N-terminal Q), oxidation (M), pyro-cmC (N-term camC), and phospho (STY) were set as variable modifications. The spectra of all phosphorylated peptides identified by Mascot were manually analyzed to confirm the site(s) of phosphorylation. Some spectra not assigned by Mascot were also manually analyzed.

2.5 Intact protein mass spectrometry

One half µL (2.6 pmol) of unphosphorylated or phosphorylated carbamidomethylated ctNHE was mixed with an equal volume of CHCA and allowed to dry on a MALDI target plate. Spectra were accumulated in mid-linear positive ion mode on the AB 4800 mass analyzer with a mass range of 4000 to 25000 m/z. Laser intensity was 3790. Accumulations per MS subspectrum were 20 for a total of 1000 shots per spectrum.

2.6 Site-directed mutagenesis of recombinant and full-length human NHE1

Recombinant ctNHE1 subcloned into the pET28a vector was used as template for site-directed mutagenesis for each potential site of phosphorylation by Rock I or Rock II using the QuickChange™ site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). To determine the impact of each potential phosphorylation site of NHE1, four sites (S268, Y649, T653, and Y559) were individually altered to an alanine. Subsequent rounds of site-directed mutagenesis to generate multiple mutations on a single construct were performed after sequence verification. cDNA of full length human NHE1 was subcloned into pCMV6 vector with a dual affinity tag (Myc and Flag) at the C-terminus of NHE1. Individual sites targeting the Rock (T653A), Rsk (S703A) or a combination of both phosphorylation sites (TSA) were mutated to alanine using the QuickChange™ site-directed mutagenesis kit.

2.7 Cell culture and stable cell line preparation

CCL39 Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas VA) and PS120 fibroblasts (NHE1 null cells derived from CCL39 cells – a gift from D. Barber, University of California, San Francisco) were cultured in high glucose DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Stably transfected cell lines containing either wild-type or mutant full length human NHE1 were produced after transfecting PS120 cells using Fugene-6 (Roche Biochemical) in serum-and antibiotic-free OptiMEM 1 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), incubating the cells overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator and then subjecting cells to 1 mg/mL G418 for three passages. Following selection, PS120 cells expressing NHE1 (PSN) were maintained by culturing in high glucose DMEM medium with 10% serum containing 0.25 mg/ml G418. NHE1 stable expressing cells were serial diluted to obtain single cell clonal isolation. Twenty isolated clonal cell lines were selected and tested for recombinant NHE1 expression and membrane distribution using immunofluorescence. Cell lines that expressed similar levels of recombinant NHE1 (as determined by western blot – see results) were used for experiments. Prior to use in each experiment, cells were cultured in medium without G418 to reduce the impact of selection agent.

2.8 Immunofluorescence microscopy

To detect the expression and location of NHE1 in PS120 cells, 20 or more individual clonal isolates cultured on glass coverslips were fixed with 7.4% paraformaldehyde and permeablilized with 0.1% Triton X 100. To block non-specific antibody binding, cells were treated with PBS containing 1% BSA and 1% normal serum. After washing with warmed PBS containing 0.1% BSA, the samples were incubated with anti-Flag mouse antibody (1:2000, mAb clone 4C5 from Origene) in the presence of PBS containing 1% normal serum and 1% BSA for one hour at 30°C. Samples were then washed three times with PBS including 0.1% BSA, incubated with Cy2-conjugated Affinity Pure Donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:2000, Jackson Labs) for one hour, washed three times and mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM-510 Meta confocal microscope.

2.9 Intracellular pH determination

Single cell steady-state pHi was measured using the pH-sensitive fluorescent dye, 2′,7′-bis-(carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF). Cells were cultured on glass coverslips in bicarbonate free complete medium or bicarbonate free medium with minimal FBS (0.5% FBS) for 24 hours prior to assay. The cells were incubated with 3.2 µM of the uncharged acetoxymethyl ester form of BCECF (BCECF-AM, Molecular Probes) for 20 min at 25 °C in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.40 at 37 °C, 145 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Glucose (Na buffer). The initial rate of alkalinization after an acid load was determined in each cell line using the ammonium chloride pre-pulse technique (20 mM NH4Cl in Na Buffer with the NaCl reduced to 125 mM) and incubated for 15 min. This loading period was followed by five min of choline buffer (145 mM choline chloride, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.58, 3 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Glucose). During acid loading, pulsing the cells with NH4+ induced an alkalinization of the cytosol that was followed by an intracellular pH acidification when NH4+ was removed in a sodium free solution. The rate of recovery from the ensuing acid load was measured for 15 min while cells were perfused with Na buffer. The fluorescence intensity of emission was measured in glass bottom dishes on an Olympus IX70 using an emission wavelength of 525 nm. The dye was excited alternately at the pH-sensitive wavelength of 502 nm and the pH-insensitive isoexcitation wavelength of 439 nm. Fluorescence intensity for each excitation wavelength was corrected for background fluorescence by subtracting intensities from adjacent areas in each field. An average of 60 cells was identified for each measurement. pHi was determined by the fluorescence intensity ratio method with a calibration curve generated using the K+-Nigericin method. dpHi/min was determined by calculating the slope of the first 30 to 40 s of the recovery.

2.10 Stress fiber formation

Treated and control cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Actin stress fibers were stained with 0.5 µg/mL phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 488 for 60 min. The cells were treated with Prolong anti-fade reagent prior to mounting the coverslips on glass slides. Cells were analyzed using an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope in fluorescence mode using a 100× objective. Cells displaying significant and strong stress fibers (well formed and prominent fibers which were organized and stretched through the majority of the cell) were counted in five random fields for each slide. The percentage of cells displaying stress fibers was determined as the total number of cells with stress fibers vs. the total number of cells evaluated in the observed fields.

2.11 Migration assay

Cells were incubated in serum-depleted medium (0.5% FBS) for 24 hours. Cells were enzymatically detached from culture flasks, washed twice to remove residual trypsin and stained with 4 µg/mL calcein-AM (Molecular Probes). Cells (1×106) were seeded into the top insert of a FluoroBlok transwell migration culture insert (BD Biosciences). Both the upper and lower chambers contained low serum medium without or with agonist. Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Cells clearly migrating through the pores were determined by counting five random fields using an inverted Olympus IX70 microscope in fluorescence mode using a 20× objective.

2.12 XTT proliferation assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed by the reduction of XTT (2.3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxyanalide) from Trevigen (Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were plated at 1×103 cells/well in a 96 well plate and incubated 12 hours to allow for attachment. The cells were then made quiescent by incubating for 16 hours in low serum (0.5% FBS) medium. The cells were then incubated in low serum medium containing treatments as indicated for 24 hours. XTT reagent was added to each culture well to attain a final concentration 0.3 mg/mL and absorbance read at 490 nm with a reference of 630 nm.

3. Results

3.1 ROCK Directly Phosphorylates the carboxyl terminus of human NHE1

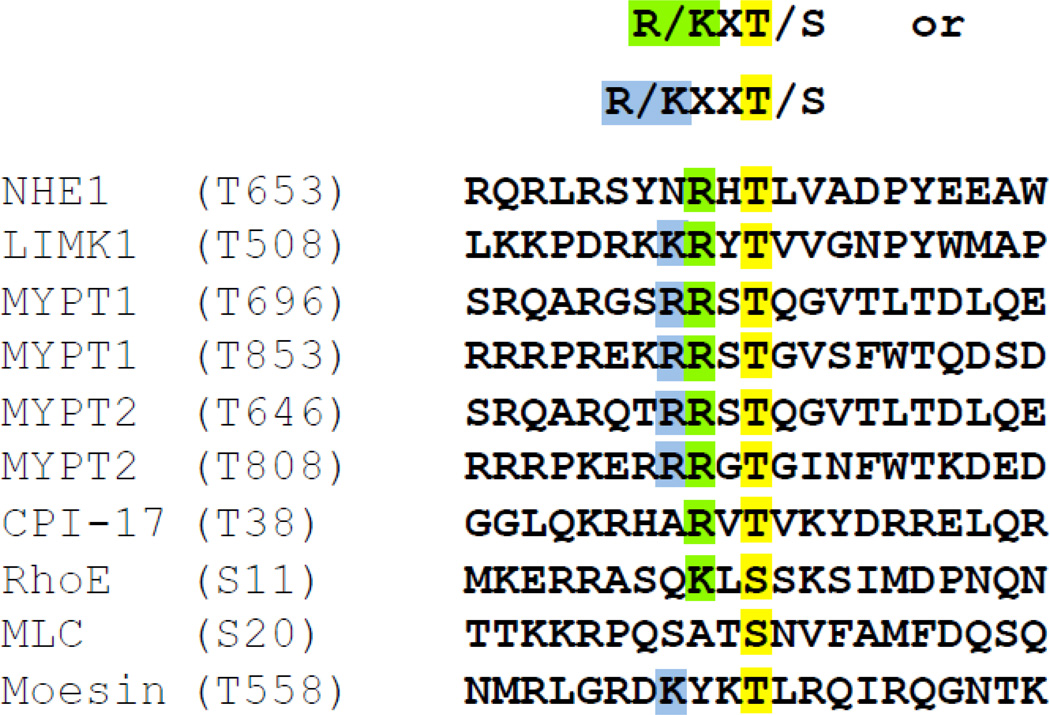

Two of the first identified downstream effectors of the GTPase Gα13 were RhoA and NHE1. Since then, several studies have demonstrated that LPA activation of RhoA and Rock regulates NHE1-dependent exchange, stress fiber and motility. Reconstitution assays and expression of constitutively active Rock revealed the C-terminus of NHE1 as a Rock substrate but not the specific residues of the phosphorylation (16–19). Complicating the identification of the Rock phosphorylation site of NHE1 is that Rock is a serine/threonine kinase with a poorly defined substrate consensus sequence (Fig. 1). Seven of the sequences shown in figure 1 contain a known threonine phosphorylation whereas two Rock substrates, RhoE and Myosin Light Chain (MLC) are phosphorylated at a serine residue. We compared several known Rock substrates, used the predicted Rock consensus sequence (20, 30, 31) and the human NHE1 amino acid sequence to identify a putative NHE1 Rock phosphorylation site (T653).

Figure 1. Alignment of putative Rock phosphorylation site of human NHE1.

Top: Rock I and Rock II consensus sequence where X is any amino acid. Bottom: Amino acid sequence of predicted (NHE1) and known Rock substrates. Yellow shaded boxes are confirmed or proposed Rock-phosphorylated serine or threonine residues. Blue shaded box highlights positive charged lysine (K) or arginine (R) residues two positions amino from serine or threonine. Green shaded boxes indicate positive charged amino acids one residue from phosphorylated amino acid.

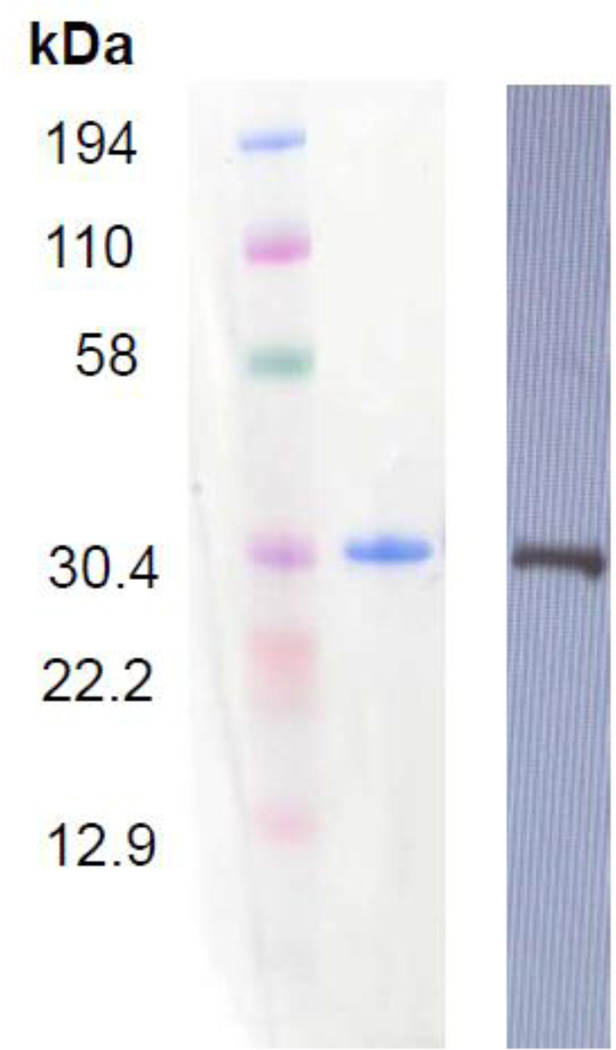

To determine if the putative NHE1 phosphorylation site, T653 was directly phosphorylated by Rock, we generated and purified a truncated, codon-optimized human NHE1 (612–815; ctNHE1) construct with an affinity tag for expression in E.coli. The recombinant ctNHE1 protein was purified as a single band which was recognized by anti- NHE1 antibody (Fig. 2). These results indicate that the band migrating at 30 kDa is ctNHE1.

Figure 2. Expression and purification of recombinant carboxy-terminus of NHE1.

Expressed and purified ctNHE1 was subjected to SDS PAGE and western blot analysis. Ten µg of purified recombinant ctNHE1 was visualized by coomasie-blue stain (left) and monoclonal antibody raised against the C-terminus of human NHE1.

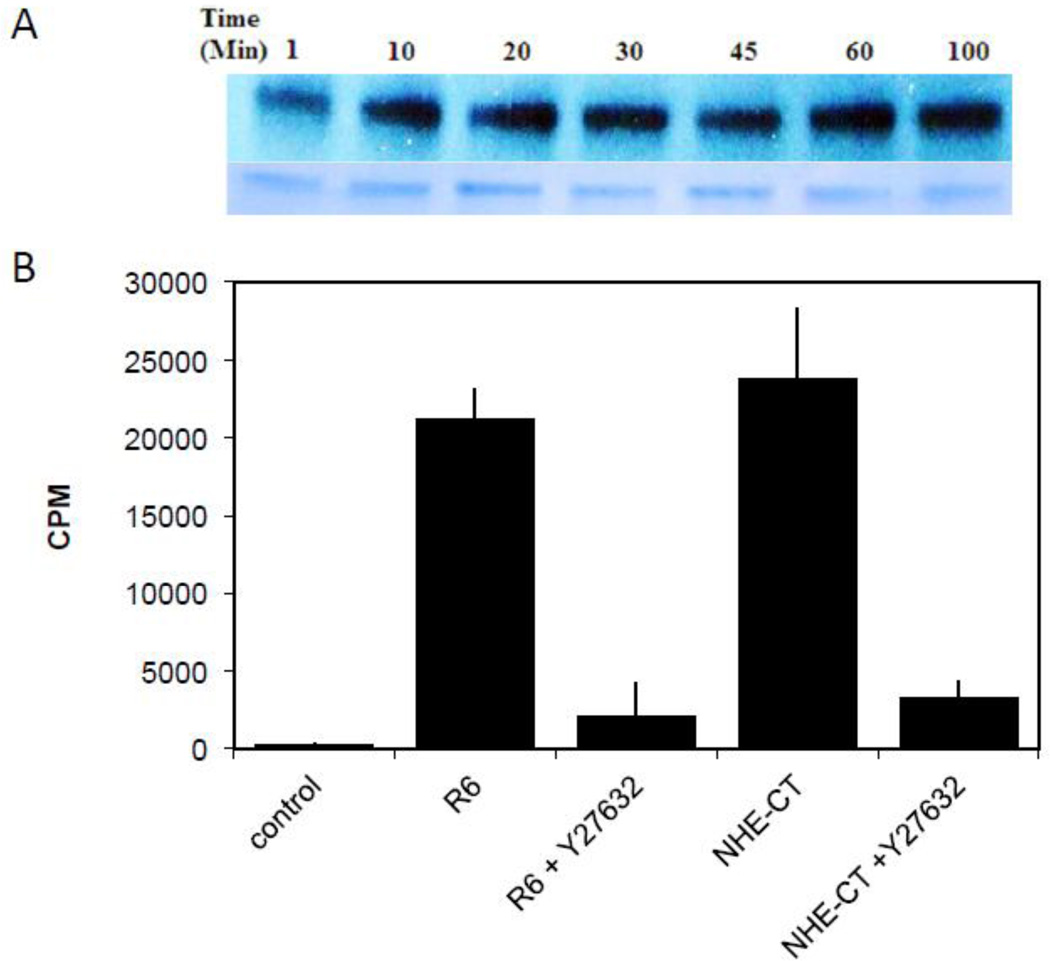

We next determined if the purified recombinant ctNHE1 protein would be phosphorylated by Rock I in an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 3). Autoradiography identified that the ctNHE recombinant protein was phosporylated in a time-dependent manner. To further characterize the Rock phosphorylation of ctNHE1, 32P-radiolabeled protein was captured and quantitated using a filter based kinase assay. Both control peptide R6 (a known substrate for Rock) and ctNHE were phosphorylated by Rock. This Rock-dependent phosphorylation was decreased to near background levels when the reaction mixture was pretreated with the Rock inhibitor Y27632 (Fig. 3). These data confirm the direct phosphorylation of NHE1 as previously determined (16, 17, 19).

Figure 3. In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant NHE1 by Rock I.

A, recombinant Rock I was reconstituted with radiolabeled ATP and ctNHE1 for the indicated times. The reaction was stopped by boiling in SDS PAGE sample buffer and 5 µg of ctNHE1 and then subjected to 12% SDS PAGE. The resulting autoradiography of an experiment completed in duplicate is shown. B, 25 µg of either known Rock substrate, peptide R6 (Ribosomal Long S6 Kinase peptide) or ctNHE1 in the absence or presence of the Rock inhibitor, Y27632 (5 µM) for ten minutes. The reaction was terminated in 75 mM phosphoric acid and filtered on Whatman filter paper to detect 32P incorporation into the peptide. Results are shown as n=4.

3.2 Determination of ROCK phosphorylation site of ctNHE1

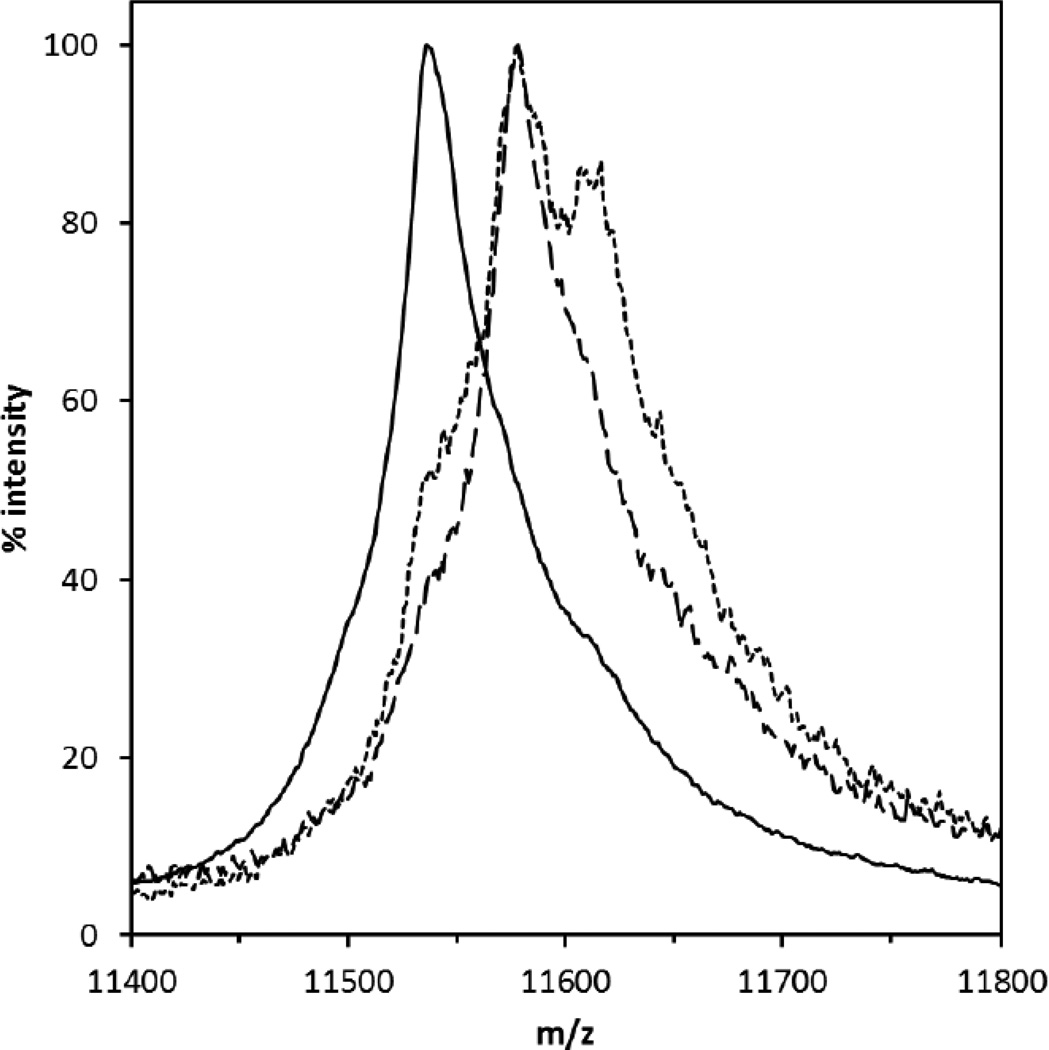

To investigate site-specific residues phosphorylated by Rock isoforms I and II, purified His-tagged recombinant ctNHE was used as a substrate for Rock I and Rock II. Intact mass determination by linear positive ion mode MALDI mass spectrometry revealed a 40 m/z increase in MH2+ ions of both the Rock I- and Rock II-phosphorylated ctNHE1 with respect to unphosphorylated ctNHE1 (Fig. 4). This shift is consistent with the stoichiometric addition of a single phosphate modification of 80 Da. The symmetry of the Rock I-phosphorylated ctNHE1 indicates that the singly phosphorylated species is by far the dominant form. The Rock II ctNHE1 profile has a shoulder corresponding to unphosphorylated ctNHE1 and a side peak that is shifted by another 40 m/z suggesting the presence of a small amount of doubly phosphorylated ctNHE.

Figure 4. Linear mode MS of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated intact ctNHE.

Shown are the MH2+ spectra of unphosphorylated (solid line), Rock 1-phosphorylated (dashed line), and Rock 2-phosphorylated (dotted line) ctNHE. The MH1+ and MH3+ ions were also observed (not shown). The mean of the neutral masseswere calculated from the MH1+, MH2+, and MH3+ precursors, The observed average mass of the unphosphorylated ctNHE is 23,089 Da ± 6 s.d. The Rock 1- and Rock-2 phophorylated ctNHE masses were 23,167 Da ± 6 s.d. and 23,163 ± 9 s.d. respectively. The calculated average mass of carbamidomethylated ctNHE is 22,990 Da.

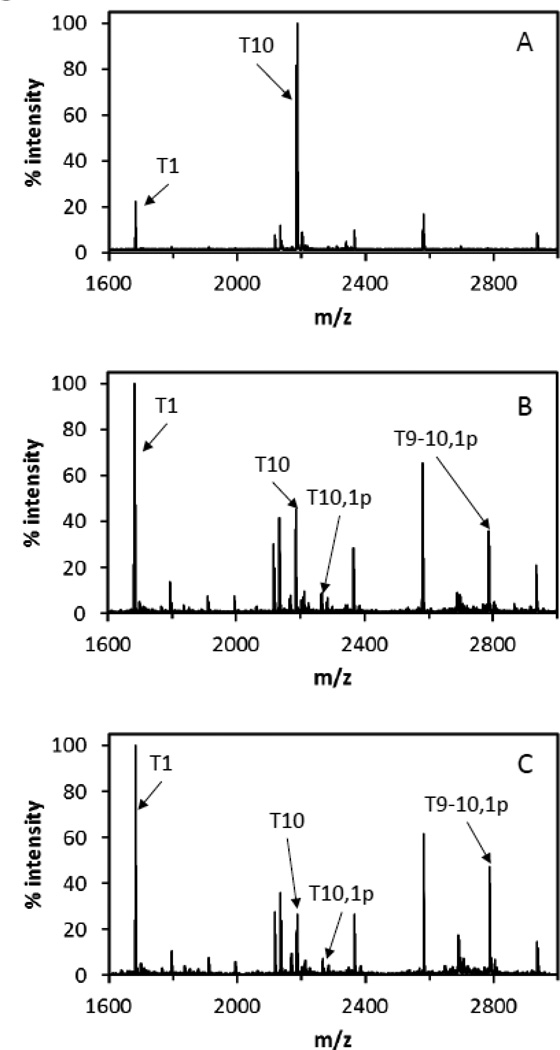

Trypsin digestion of ctNHE1 in its phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms followed by MALDI MS yielded 66% to 77% sequence coverage of ctNHE (Fig. S1, Table S1). This coverage included 19 out of the 25 Ser and Thr residues in the sequence. Peptide mass fingerprints (Fig. 5B, 5C) showed a prominent loss of peptide T10 upon phosphorylation by either Rock I or Rock II when compared with that of unphosphorylated ctNHE1 (Fig 5a). Concurrent appearances of a family of T10 peptide or T10-containing missed cleavage peptides with 80 Da mass shifts (T10,1p; T9–10,1p) were consistent with the addition of one phosphate in this region of ctNHE1. Peptide mass fingerprinting therefore revealed the primary site of phosphorylation by Rock I and Rock II on the ctNHE1 is localized to the T10 region of the peptide which contains two candidate phosphorylation sites, T653 and Y659. Additional candidate phosphorylation sites at S648 and Y649 are present in T9–10.

Figure 5. Peptide mass fingerprints of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated ctNHE.

Labeled peptides illustrate the change in trypsin efficiency in cleaving the T9–10 peptide upon phosphorylation by Rock 1 or Rock 2. The T1 peptide, which is unchanged upon phosphorylation is used as a reference for the relative loss in intensity of the T10 peptide upon phosphorylation and the appearance of T10,1p, T9–10,1p, and T9–10,2p peptides. A unphosphorylated ctNHE, B Rock 1-phosphorylated ctNHE, C Rock 2-phosphorylated ctNHE.

Phosphorylation affected the efficiency of proteolysis of ctNHE1. Trypsin digestion of unphosphorylated ctNHE1 yielded the T10 peptide, which was the most intense ion in the ctNHE1 peptide mass fingerprint, but no T10-containing missed cleavages (Fig. 5a). The loss of T10 peak intensity upon phosphorylation by Rock I or Rock II (Fig. 5b and 5c) correlated with 90% and 94% phosphorylation of T10 respectively. The appearance of T10 missedcleavage peptides in the phosphorylated ctNHE1 trypsin digests is consistent with the interference of trypsin action by phosphate groups near the T9–10 cleavage site.

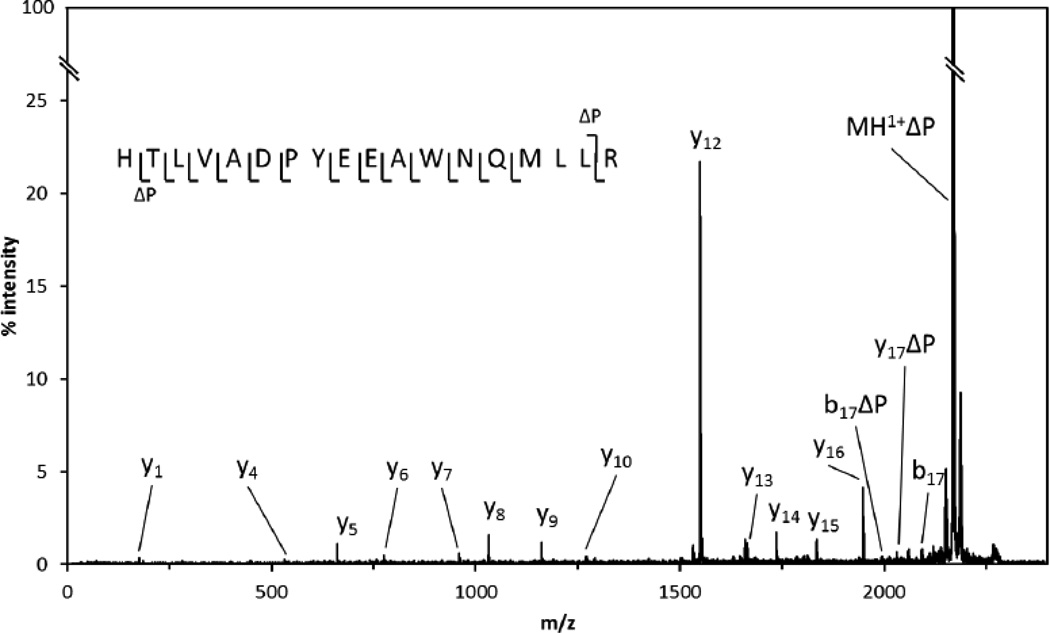

Peptide identities were confirmed by MSMS (Table S1). Peptide T10 contains potential phosphorylation sites at T653 and Y659. The MSMS of T10,1p from Rock I-phosphorylated ctNHE1 (Fig. 6) and Rock II-phosphorylated ctNHE1 showed strong neutral loss of phosphoric acid (−98 Da) for the parent ion. This and multiple b and y ions strongly support the localization of the phosphate to T653 as opposed to Y659. A similar MSMS was obtained for the Rock II-phosphorylated T10 peptide (not shown). The Rock I- and Rock-II phosphorylated ctNHE1 both yielded T9–10,1p in which T653 was the dominant site of phosphorylation (spectrum for the Rock I peptide is shown in Fig. S2). Though the relatively strong b10-80 ion could be interpreted as arising from neutral loss of PO3 from phosphotyrosine, the lack of other supporting fragments for this site argues against a subset of this peptide being phosphorylated at Y659.

Figure 6. Tandem mass spectrum of the singly phosphorylated T10 peptide.

Neutral loss of phosphate (ΔP) is 98 Da. The C-terminal (y) and N-terminal (b) fragment ions are indicated.

A doubly phosphorylated T9–10 peptide (T9–10,2p) was seen in the peptide mass fingerprints of Rock I phosphorylated ctNHE1, but with one-tenth the ionization intensity as the T9–10,1p (not shown). The second minor Rock I site could not be localized by MSMS, but the presence of −98 and −80 neutral losses leaves open the possibility that it might be either S648 or Y649 (Fig. S3). Evidence could not be obtained to account for the second minor phosphorylation site introduced by Rock II as suggested by intact mass measurements in figure 4.

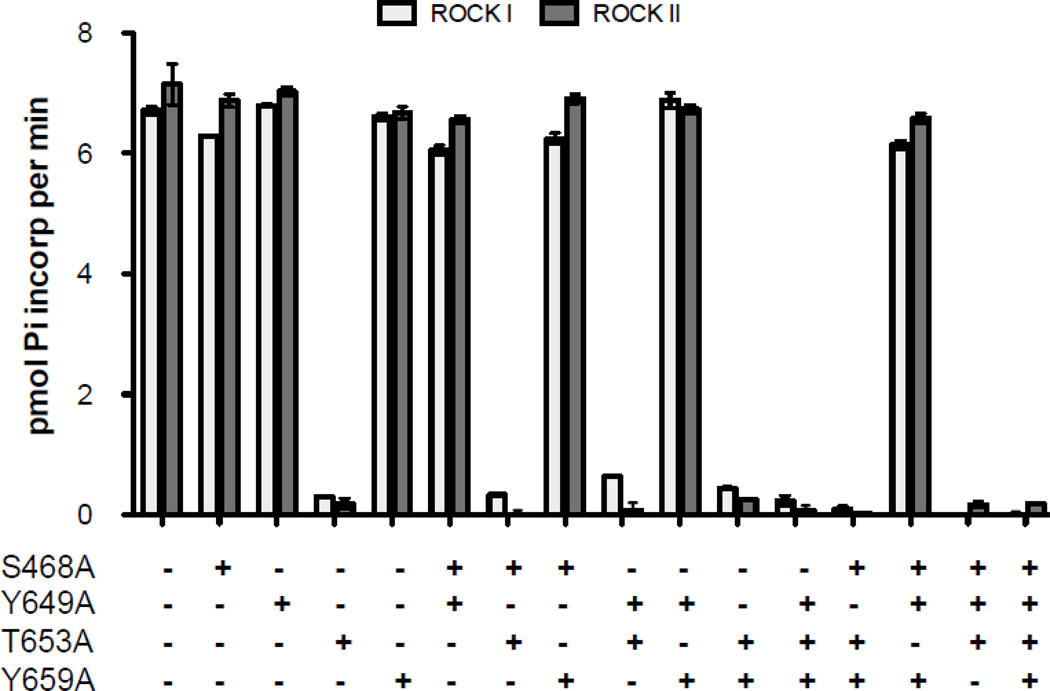

We then constructed a series of recombinant His-tagged ctNHE1 fusion constructs to confirm the phosphorylation results observed using mass spectroscopy. Each major and minor amino acid identified after tryptic digest was substituted to an alanine (S648A, Y649A, T653A or Y659A) in all possible combinations at each of the four residues. Each recombinant protein (25 µg) was subjected to an in vitro kinase assay with either Rock I or Rock II in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP. Radiolabled recombinant protein was detected using a Whatman filter-based assay (Fig. 7). Both isoforms of Rock phosphorylated the wild-type ctNHE1 protein equally well with nearly one-to-one stoichiometry in agreement with the intact mass result (Fig 4). Each assay contained 1.071 nmol recombinant protein with a five fold excess ATP (5.00 nmol). Specific activity of [γ-32P] ATP mixture was used to determine 0.946 +/− 0.022 nmol phosphate was incorporated into wild-type recombinant NHE1 in the presence of Rock I and 1.028 +/− 0.014 nmol phosphate incorporated in the presence of Rock II. Loss of phosphorylatable sites at residues 648, 649 or 659 did not cause a significant decrease in radiolabeled protein phosphorylated by Rock I or Rock II. However, when T653 was converted to an alanine, both kinases were unable to phosphorylate the protein. Less than 2% of total [γ-32P] ATP was detected when T653A was incubated with either Rock kinase. This pattern was observed in the double or single mutants, where the level of radiolabeled protein was at or near the level of phosphorylation when all four residues were altered to an alanine. A minor phosphorylation inhibition (4%) by Rock I but not Rock II was detected when S648 was altered, indicating a small potential secondary phosphorylation by one of the two kinases. The mass spectrophotometry analysis coupled with the in vitro kinase indicate for the first time that the C-terminal domain of human NHE1 is selectively phosphorylated at T653 by both Rock I and Rock II kinases.

Figure 7. Analysis of NHE1 phosphorylation by Rock I and Rock II.

Phosphorylation of 25 µg of recombinant ctNHE1 was determined after 30 min of reaction with 0.5 µg of either purified Rock I or Rock II. Phosphorylated peptide was determined by phosphocellulose filter binding and quantitated by scintillation counter. Data are presented as the incorporated radioactivity with respect to control (no kinase or substrate). Values represent the mean ± SEM (n=4).

3.3 Impact of Rock and Ribosomal S6 kinase phosphorylation of NHE1 transport

NHE1 is phosphorylated by a surprising number of protein kinases. Earlier work found the ERK substrate, Rsk, phosphorylates NHE1 at S703 and is responsible for increased transport in response to serum (23). As mentioned earlier, NHE1 is phosphorylated by Rock in response to a number of agonists including LPA. Pharmacological inhibition of either the RhoA-Rock or ERK-Rsk pathways separately resulted in the partial inhibition of the LPA-activation of NHE1 transport, however when both pathways were inhibited LPA-induced NHE1 activity was completely abrogated (29). While this work showed the potential role for Rock and Rsk in regulating signaling to NHE1, the role for a direct phosphorylation of Rock or the role of either phosphorylation of NHE1 on its transport activity remained unanswered.

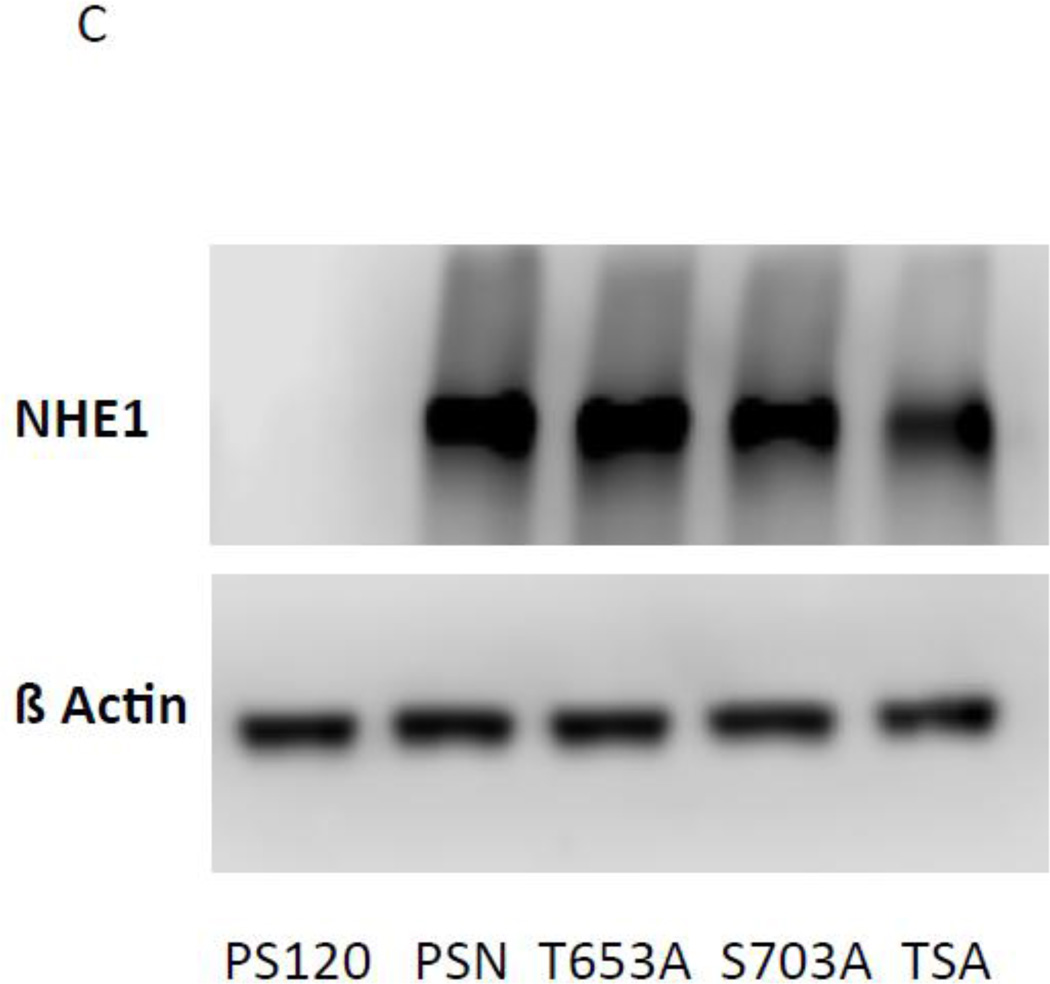

To study the effect of Rock and Rsk on NHE1 transport we stably expressed DDK (DYKDDDK-Flag)-tagged, full-length human NHE1 wild-type and serine or threonine-to-alanine NHE1 mutants in PS120 fibroblasts (a description of each cell line can be found in Fig. 8a). PS120 fibroblasts are a derivative cell line of the CCL39 lung fibroblast cell line, do not express NHE1, and are thus a good model to study the impact of NHE1 on cell function (32, 33). Twenty clonal isolates for each cell line were generated and NHE1 expression determined by immunofluorescence. Only isolates with 100% NHE1 staining were selected for further analysis. The subcellular distribution of the tagged human NHE1 was examined by confocal microscopy (Fig. 8b and supplementary Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 8b, cells transfected with NHE1 displayed strong labeling at the periphery of the cell with some intracellular, possibly endosomal labeling. Similar labeling at the margins of the cell was observed for each mutant strain (supplemental Fig. S4). The level of NHE1 expression of wild-type and each mutant was determined by westernblot analysis of total cell lysates (Fig 8c). PS120 cells do not express NHE1 (Fig 8c and blotting data not shown), and each stable NHE1 expressing cell line display similar levels of recombinant NHE1 (Fig 8c).

Figure 8. Expression of full length NHE1 in PS120 fibroblast.

A, description of cell lines stably expressing mutant or wild-type full-length epitope-tagged NHE1. B, representative confocal image of cells labeled with monoclonal anti-Flag (Origene) to visualize localization of full-length NHE1 expressed in PS120 fibroblasts. White arrows identify predominant peripheral staining of fixed cells. See supplementary figure S4 for controls without antibody and images from additional NHE1 expressing cell lines. C, Western blot analysis of recombinant full-length NHE expression. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and 30 µg of each sample was subjected to SDS PAGE. Expression of NHE1 and β actin of the same blot was determined by immunoanalysis.

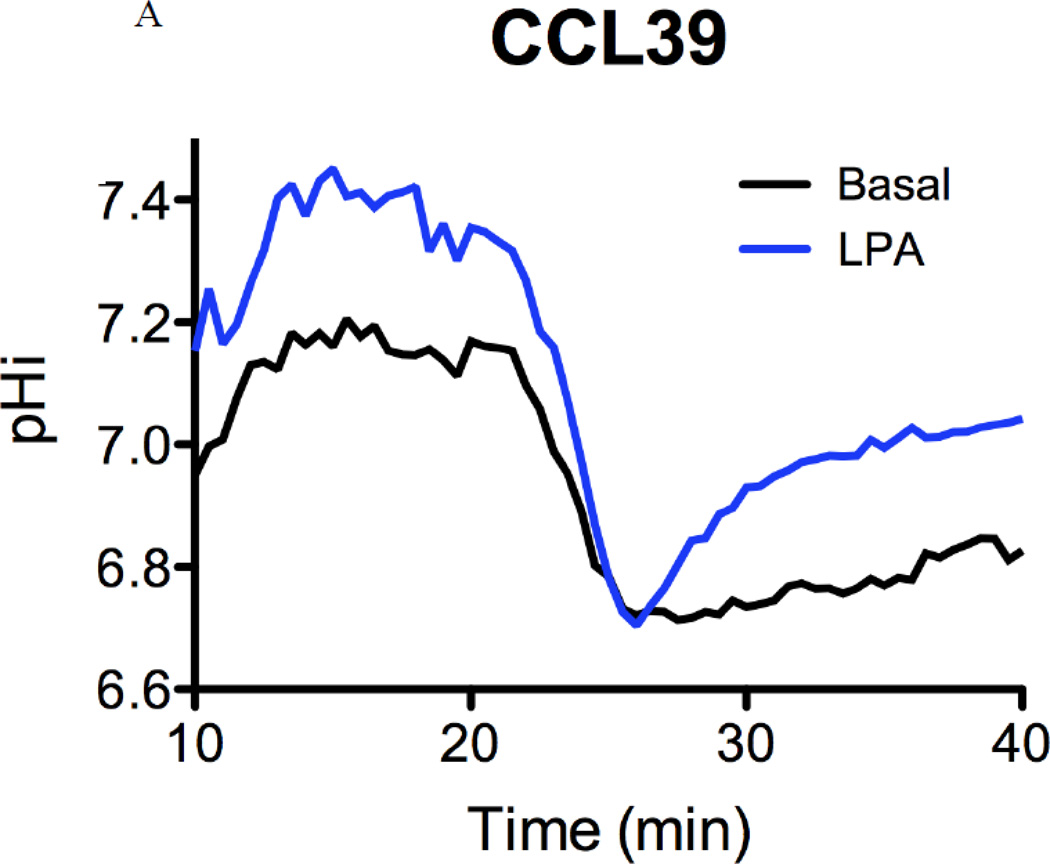

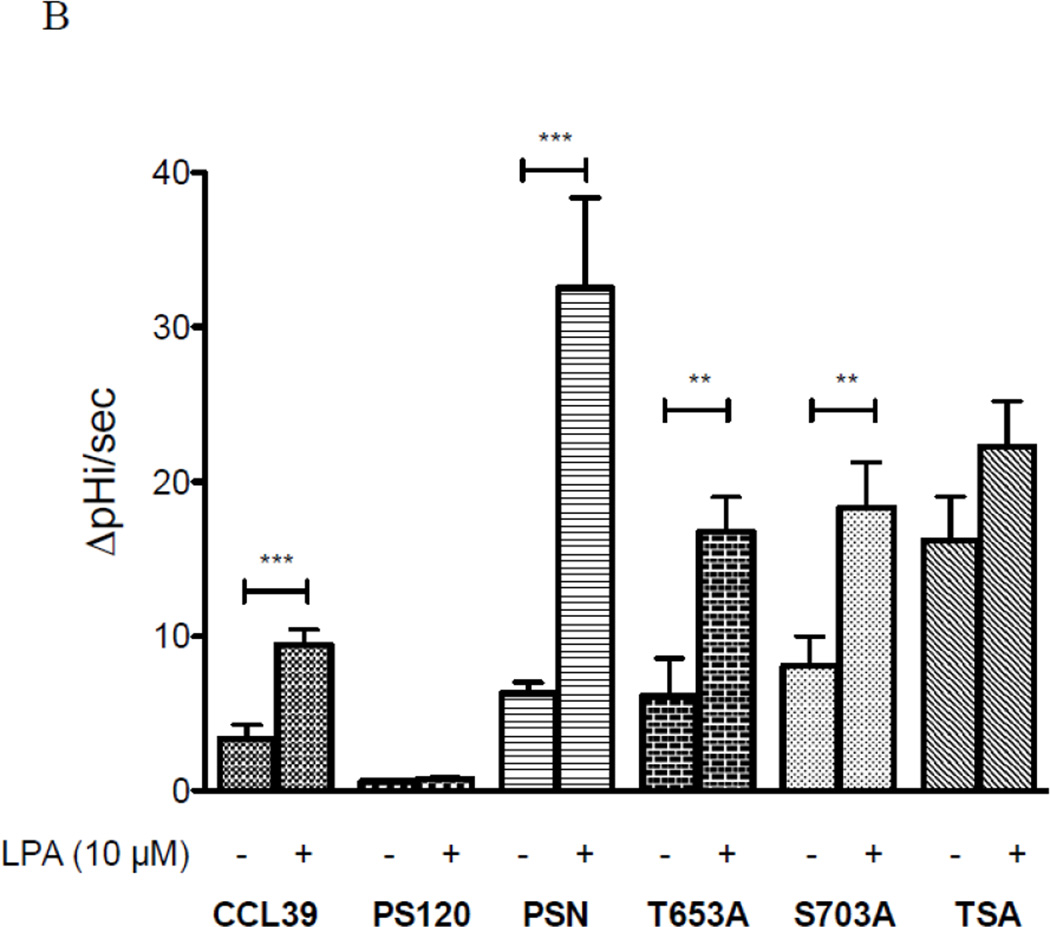

To examine the impact of each mutation on NHE1 transport, we subjected cells to acid load without and with agonist and determined the rate of recovery (Fig 9A). As expected, the rate of proton transport after acid load showed a twofold increase in the presence of LPA compared to control cells while LPA had no significant impact on acid load recovery in PS120 cells (Fig 9A and 9B). As expected, LPA-inducible acid load recovery was reconstituted after NHE1 was stably expressed in PS120 cells (Fig 9B and 9C, PSN cells). Consistent with our earlier work using small molecule inhibitors against Rock or MEK which only blocked half of the LPA stimulated-NHE activity, we show here that cells expressing either T653A or S703A display a diminished response to LPA ((28) and Figs. 9B). Interestingly, when both the Rsk and Rock phosphorylation sites were altered to alanine, the basal transport rate was nearly double that of the wild-type NHE expressing cells and unresponsive to LPA (Fig. 9B). The impact of these two kinases on NHE1 transport is further highlighted when comparing the change in rate of recovery before and after LPA stimulation (Fig. 9C). PSN cells showed a nearly three-fold increase in LPA-activated transport compared to CCL39 cells. This is likely due to the 2.5 fold overexpression of NHE1 in PSN cells as compared to endogenous NHE1 expression in CCL39 cells (data not shown). However the differences between the NHE1 expressing cells is unlikely due to different expression level or location of reconstituted NHE1 expression as these cells were selected for similar membrane expression levels (Fig 8b and supplementary figures). LPA-stimulated NHE1 proton exchange increased 6.13 +/− 0.707 SEM) fold over control. Yet cells expressing either the T653A or S703A mutation gave half the LPA fold increase (2.44 +/− 0.874 SEM and 2.83 +/− 0.932 SEM) as control cells (Fig 9C). These data indicate that each phosphorylation site has an additive effect on LPA-induce NHE1 activation, suggesting that both the Rock and Rsk phosphorylation sites of NHE1 are cooperative for the complete activation of NHE1 transport by the LPA receptor.

Figure 9. Wild-type and mutant NHE1 proton transport.

Serum-deprived quiescent cells, dye-loaded with BCECF seeded on a quartz coverslip were perfused with 20 mM ammonium chloride for 15 min. The change of pHi (proton transport after acid load) was observed after cells were perfused with buffer including sodium (Na Buffer). To determine the impact of LPA on proton transport, 10 µM LPA was included in both ammonium chloride and Na buffers. A, effect of LPA on CCL39 cells expressing endogenous NHE1. Each trace consists of response from 60 or more individual cells. B, Summary of initial rate of pHi change from acid load for cells in the presence or absence of 10 µM LPA. Values are mean ± SEM of at least six experiments. Statistical analysis was determined using a two-tailed type one student T-test (without and with LPA). C, Fold change in rate of acid load recovery response to LPA addition over control was determined for each cell line. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a non-paired one-way Anova (p>0.001) with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison with a 99.9% confidence interval. NS represents data not significantly different. ** p< 0.05 and *** p<0.001 as compared to control group.

3.4 Both Rsk and Rock phosphorylation sites in NHE1 are required for LPA-induced stress fiber formation and cell motility

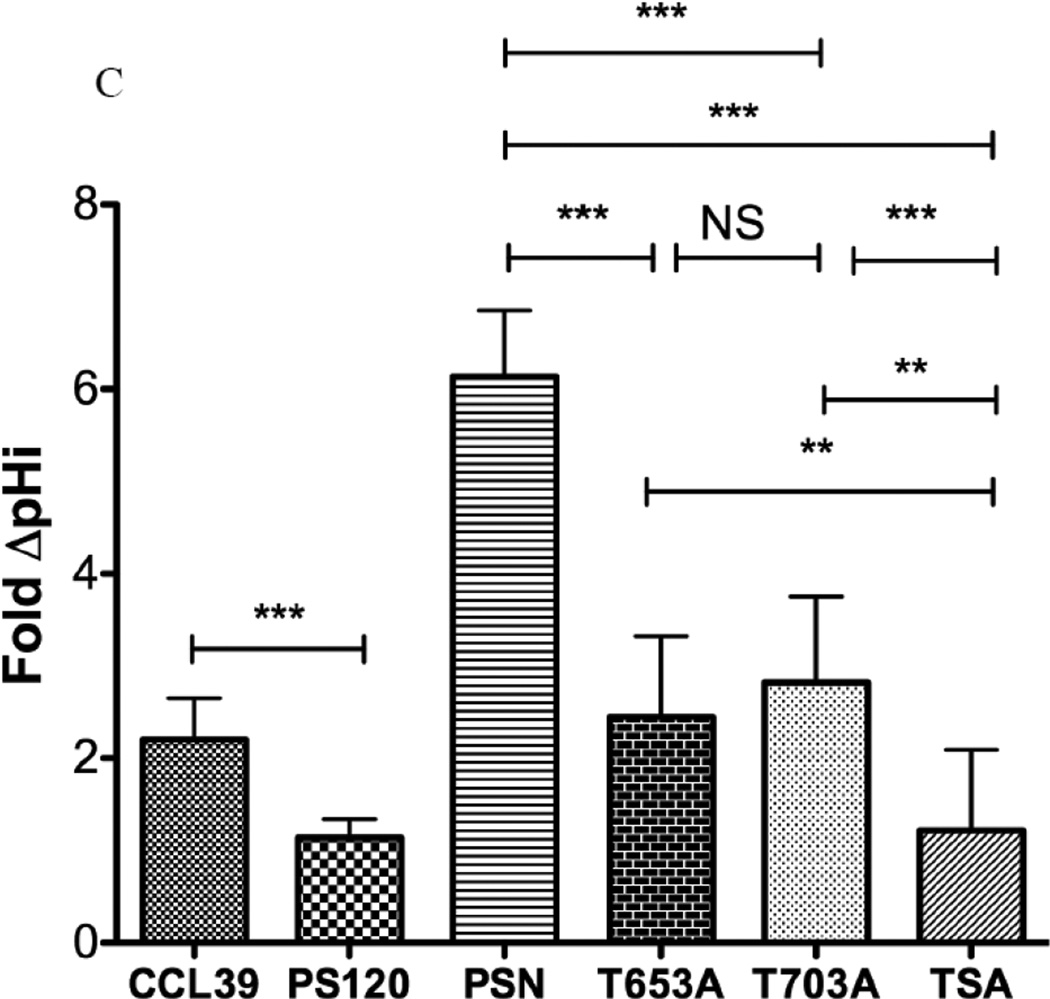

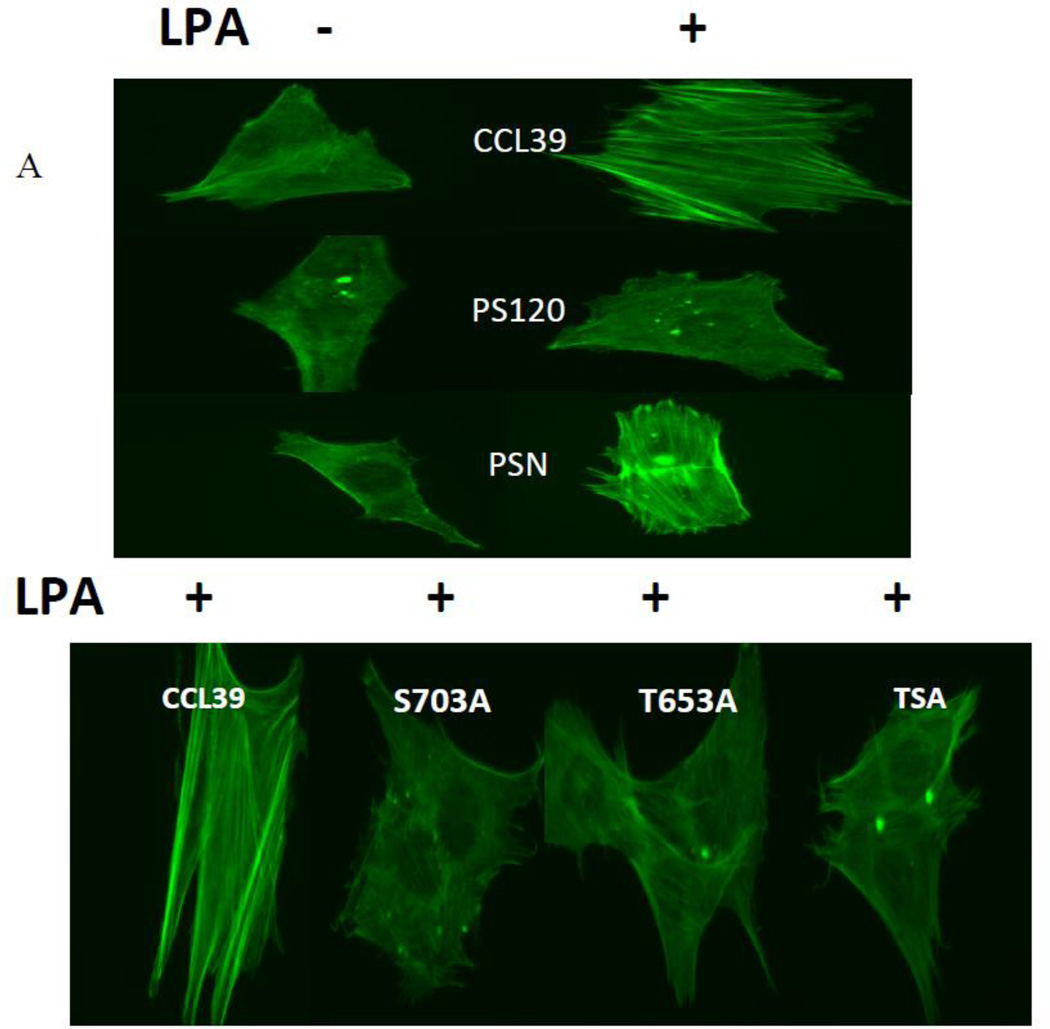

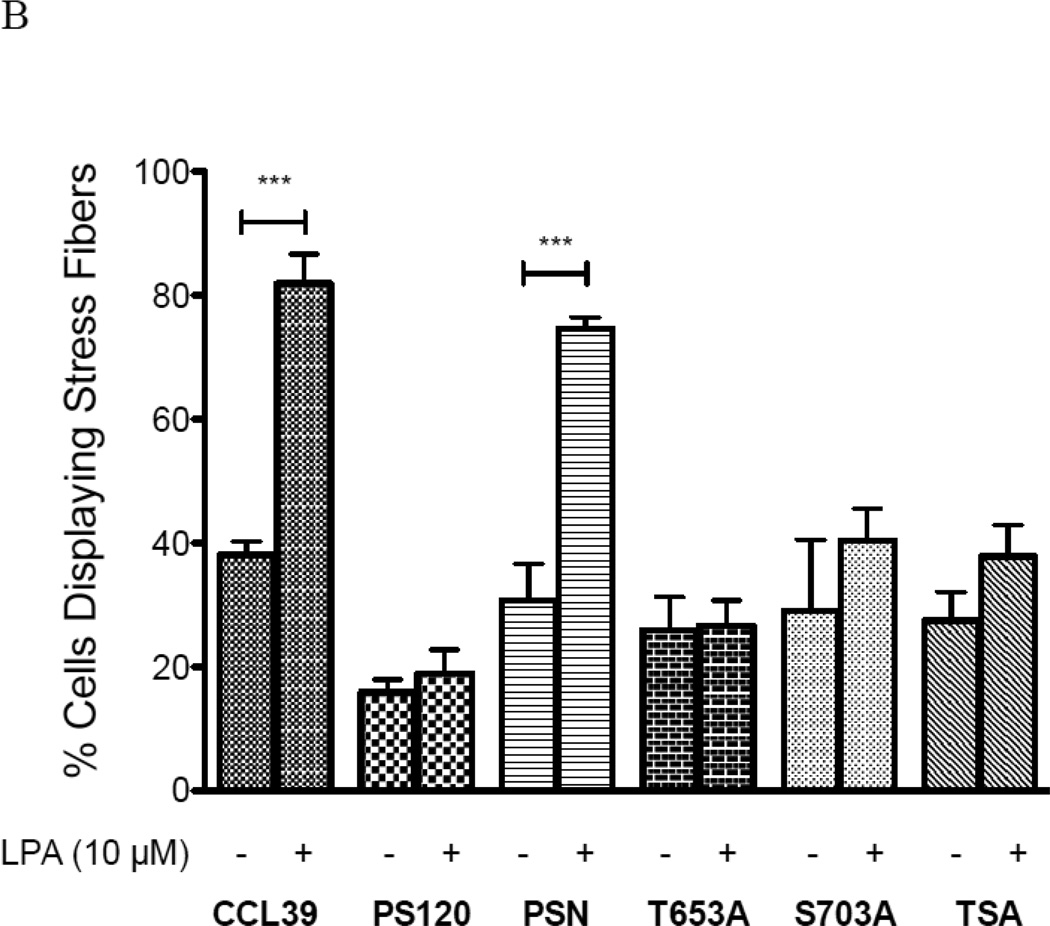

Fibroblast treated with LPA display an enhanced wound-healing rate that is dependent on NHE1 and signal through both ERK and Rock (29, 34), yet the direct impact of each phosphorylation site on NHE1-driven cell migration has not been determined. NHE1 at the leading edge of migrating cells is thought to organize stress fibers enhancing the protrusion of the cell membrane and directing migration (35, 36). And, while the role of ROCK in stress fiber assembly and migration is evident, the role of Rock-NHE1 on stress fiber formation remains unclear. Therefore, to resolve the impact and cellular significance of NHE1 phosphorylation in motility events, we next investigated the importance of Rsk and Rock phosphorylation sites on LPA-induced stress fiber formation. Fig. 10A shows the lack of organized actin structure in serum-deprived fibroblasts followed by a significant increase in stress fiber formation after addition of 10 µM LPA in CCL39 and PSN cells. Most of the cells with actin stress fibers display typical ventral stress fibers. In a minority of the cells we see stress fibers forming a transverse arc or dorsal stress fiber formation as already observed (37, 38). Addition of LPA to quiescent CCL39 fibroblasts increased the number of cells displaying stress fibers more than two fold (38.12 +/− 2% to 81.89 +/− 8% - Fig. 10B), while in PSN cells, the percentage of cells with stress fibers increased from 30.71 +/− 8 % to 74.56 +/− 3 %, giving approximately the same fold change as found in wild-type fibroblasts (Fig. 10B). Consistent with other work in PS120 cells, loss of NHE1 expression abrogates LPA-stimulate stress fiber formation (16–18, 39, 40). As expected, reconstituted wild-type NHE1 expression in PS120 cells regained the ability to form LPA-induced stress fibers (Fig 10A and 10B). While loss of either phosphorylation site only partially inhibited proton transport, mutation of either site completely blocked stress fiber formation. Cells expressing NHE1 lacking either the Rsk or Rock phosphorylation sites showed no significant increase in stress fiber formation in the presence of LPA, a result similar to that observed for PS120 cells (Fig 10B). Together, these results indicate that phosphorylation-dependent transport is uncoupled from the role of either Rsk or Rock in the formation of stress fibers.

Figure 10. LPA-induced stress fibers and NHE1 phosphorylation.

Fibroblasts were grown to a 30–50% confluency on a glass cover slip. After being placed in 0.5% serum overnight cells were stimulated 10 µM LPA for 30 min. Cells were fixed and stained for stress fiber formation using FITC-labeled phalloidin. A, representative fluorescence micrograph of CCL39, PS120 cells and PSN cells before and after LPA addition. Effect of NHE1 phosphorylation by Rock and Rsk was observed in representative images of cells expressing wild-type and mutant NHE1. B, Quantification of stress fiber formation. Five random fields were examined for each cover slip and the average percent of cells expressing stress fibers determined for each field. Values are mean ± SEM of at least six experiments. Statistical analysis was determined using a two-tailed type one student T-test (without and with LPA). Data indicated with a *** were significantly different from the control data.

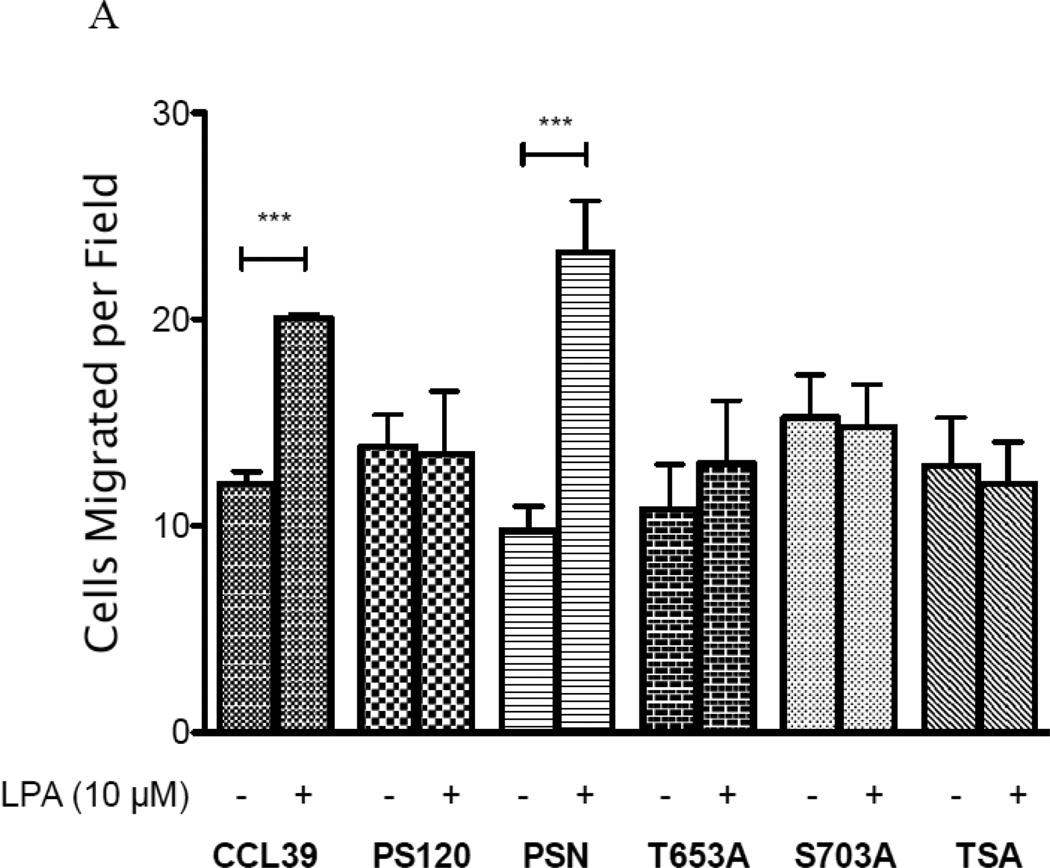

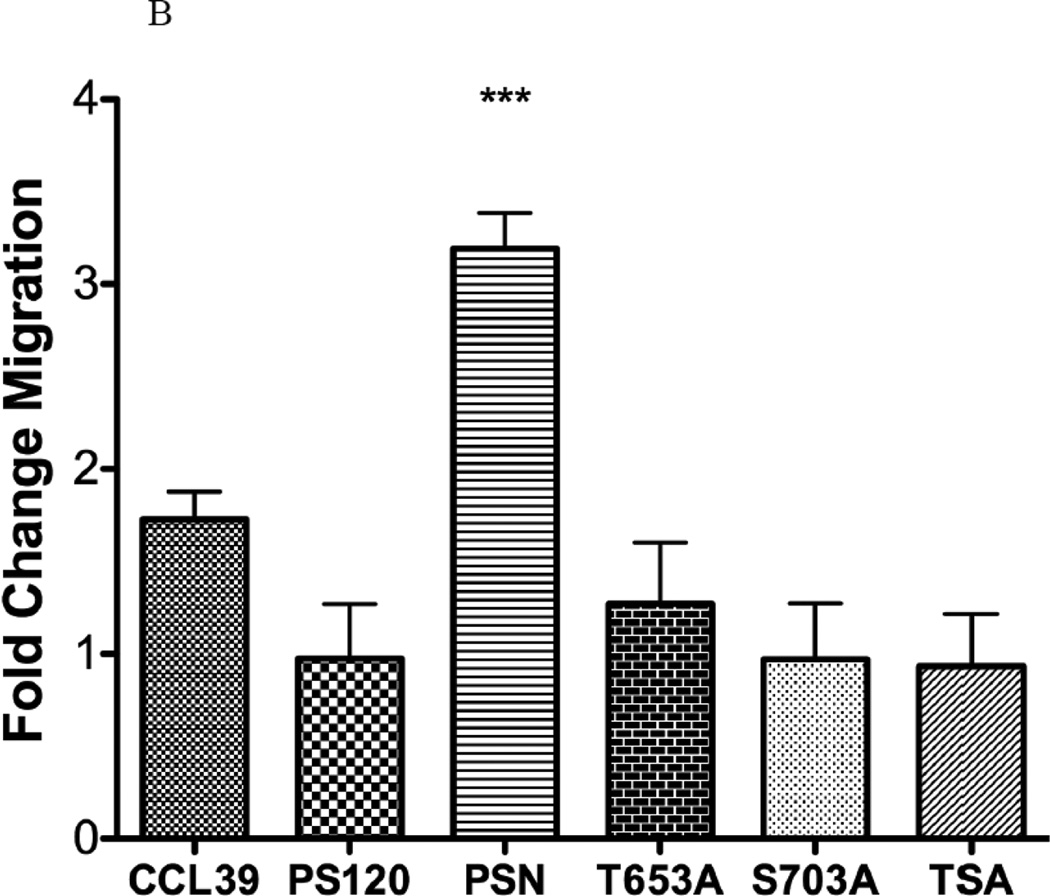

In CCL39 fibroblasts, formation of stress fibers is required for motility (37, 41). We therefore next determined the migration potential of LPA in each cell line. Not surprisingly, CCL39 and PSN cells treated with 10 µM LPA displayed a significant increase in the number of cells migrating through the transwell membrane as compared to non-stimulated, control cells (Fig 11 A&B). The role of NHE1 in migration is further demonstrated by the lack of migration in control or LPA-induced PS120 cells. This is consistent with earlier work on wound healing from our laboratory (34), where the loss of NHE1 expression blocked the ability of LPA to stimulate cell motility in PS120 compared to CCL39 cells. Furthermore, we found that loss of phosphorylation of S703 resulted in a slightly higher, but non-significant migration rate in both LPA treated and control non-LPA treated cells (Fig 11A). However the fold change in migration due to LPA was more clearly observed in Figure 11B. Here, like stress fiber formation, loss of either T653 or S703 abolished LPA-induced migration. This data further identifies that both kinases are critical for the NHE1-induced change in stress fiber formation and cell migration in response to LPA.

Figure 11. Effect of NHE1 phosphorylation on LPA-induced cell migration.

A, Cells were serum deprived for 12–14 hours and 1×106 total cells were seeded in migration chambers in medium containing 0.5% serum. Cells were then incubated overnight without or with 10 µM LPA. Cells migrating through the porous substrate were determined after staining with Calcein-AM. Each well was counted in five random fields. A two-tailed, student’s ttest was performed between control (0.5% serum) and LPA induced cells (n=4) performed twice. B, fold increase in migration between control and LPA stimulated cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis between PS120 cells and those expressing human NHE1 was performed using a non-paired one-way Anova (p>0.001) with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison with a 99.9% confidence interval. *** p<0.001 as compared to control group.

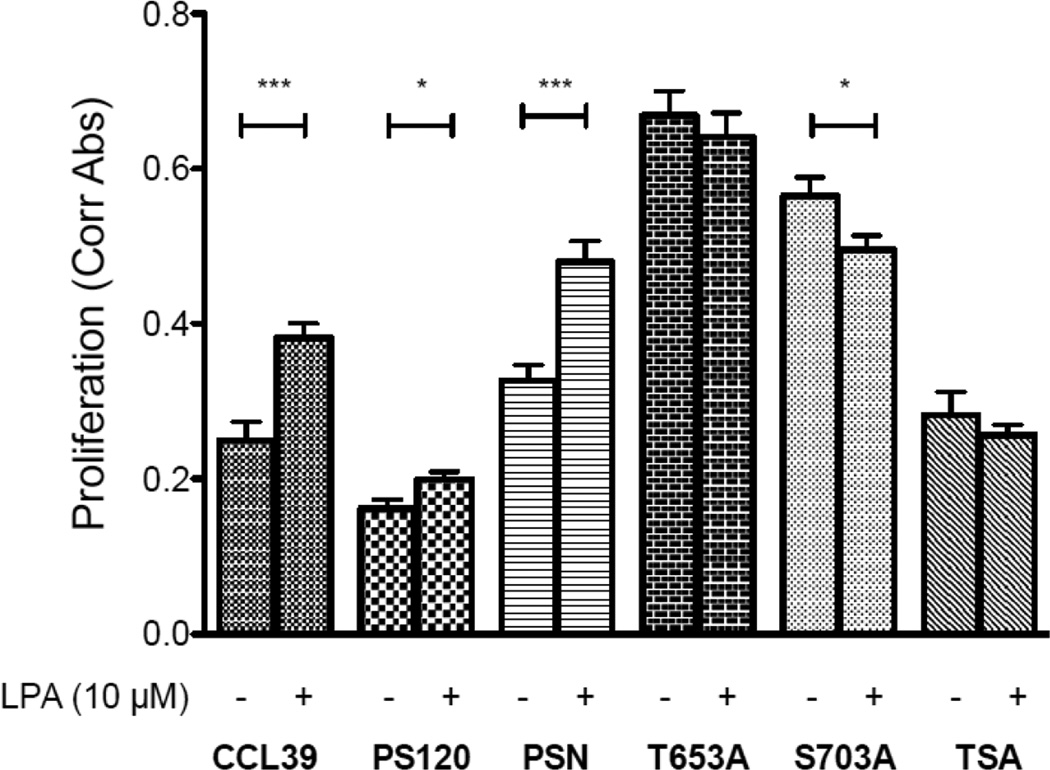

3.5 Rock and Rsk-mediated phosphorylation and regulation of LPA-mediated proliferation

Regulation of proliferation and migration are often coordinated. One of the directing factors for both cellular behaviors is NHE1 (35). For instance, in the presence of serum, loss of S703 and NHE phosphorylation by AKT has been shown to result in a decreased proliferation (42). Here, we show that in quiescent CCL39 and PSN cells, addition of LPA increased the rate of proliferation 1.53 and 1.47 fold over control, non stimulated cells (Fig 12). Surprisingly, proliferation rates in control and LPA treated cells for both S703A and T653A were substantially higher than the proliferation rate in either CCL39 or PSN cells. Furthermore, these cells showed no significant response to LPA treatment. Interestingly, the untreated double mutant TSA cell line showed a similar proliferation rate to that of PS120 cells, and similar to the single mutants or PS120 cells, LPA addition did not increase cell growth rate (Fig 12). The increase in basal rate of proliferation in the single phosphate mutants was surprising as the loss of S703 was reported to decrease cell growth in the presence of 5% FBS (42).

Figure 12. LPA-induced cell proliferation in fibroblasts expressing wild-type and mutant NHE1.

Cell proliferation of six cell lines was determined using the XTT assay. Cells (1×103/well) were seeded, allowed to attach for one day and then incubated overnight in low serum medium alone or in the presence of the indicated agonist or inhibitor for 24 hours. All data are presented as the mean +/− SEM (n≥ 8). Statistical analysis of data was performed using a two-tailed, student’s t-test.

4. Discussion

Mitogen stimulated cell motility includes activation of NHE1 in a wide range of cell types (2, 6, 9, 10, 16–19, 34, 40). For a number of years, it has been understood that several protein kinases mediate increases in NHE1 dependent, LPA-induced stress fiber formation and cell migration. Among these kinases, Rock and Rsk kinases have been implicated in regulating NHE1transport rate and stress fiber formation by phosphorylating of the C-terminus of NHE-1 (16). However, the precise residues phosphorylated and their impact on NHE1 function have remained undetermined. In this study These prior studies showed that phosphorylation of the full-length NHE1 protein lead to an increase in NHE1 transport rate and stimulated stress fiber formation (16). An understanding of the Rock-NHE1 mechanism was further complicated because Rock phosphorylates several proteins besides NHE1 that are involved in cellular motility, some of which also bind NHE1.

During our examination of the putative consensus sequences for Rock, we found a potential Rock I and II target sequence on the carboxyl-terminus of NHE1 at residue 653 (Fig 1). Mass spectrometry showed, with a near one-to-one stoichiometry, that T653 was the primary target for both Rock I and Rock II. Consistent with the phosphopeptide mapping of precipitated NHE1 (16), we found minor additional sites of phosphorylation that could have been the result of less specific secondary sites of phosphorylation. However, these secondary sites of phosphorylation are unlikely to be physiologically relevant due to the fact that site-directed mutational studies unambiguously identified the critical site of Rock phosphorylation of NHE1 to be T653 (Fig 7). Other studies have identified a number of protein kinases which phosphorylate NHE1, none of these sites overlap with the T653 site determined to be the Rock phosphorylation site (Fig 6). A comprehensive review of SwissProt, Phosphosite Plus, and Phospho.ELM databases were unable to identify any previously reported phosphorylation of NHE1 at T653. Previously, Meima et al. (42). showed the truncation of the carboxyl terminus of NHE1 up to but not inclusive of residue T653 resulted in a loss of phosphorylation while the exchanger retained some level of ability to respond to growth factors and LPA signaling. Although somewhat paradoxical to the work presented here, this could be explained by a loss of affinity fo Rock for NHE1 when the target residue is at the extreme end of the construct (16).

NHE1 transport is increased by a number of factors including phosphorylation of the regulatory cytoplasmic tail. As expected, LPA increased the rate of proton transport after acid loading (Fig 9a). In contrast to work using serum to stimulate Rsk activity, mutation of S703 to alanine only lead to a partial decrease in the NHE1 response to LPA (Fig 9B and (24)). Using growth factors and serum, Rsk has been implicated as the primary NHE regulatory kinase (22–24). However, the role of Rsk has been contradicted in both AP1 cells stably transfected with human NHE1 and in cardiomyocytes, where sustained acidosis induces a growth factor-dependent NHE1 activity through direct ERK phosphorylation of NHE1 (S770 and S771), but not Rsk (S703) (43). Interestingly, insulin and PDGF increased phosphorylation of NHE1 at S648 but not S703 in PS120 fibroblasts expressing human NHE1 (42). Furthermore, Ser to Ala mutation at NHE1 S703 had no impact in the ability of insulin, thrombin or PDGF to activate NHE1 transport. Thus, while Rsk is clearly critical for signaling related to certain growth factors to NHE1, the requirement for NHE1 S703 phosphorylation is not universal. Therefore our work adds to the complex picture of Rsk phosphorylation and regulation of NHE1 transport.

Our data for the first time support the direct and physiologically significant role for Rock phosphorylation of NHE1 (Fig. 4). RhoA-dependent activation of NHE1 was first observed in PS120 cells expressing human NHE1 while investigating Gα12/13 signaling (19, 40). This earlier study described the role of activated RhoA or Rock in directly shifting the proton exchange set point for the exchanger. This work also showed that Rock bound and phosphorylated NHE1 in an LPA-dependent fashion. The role for Rock phosphorylation of NHE1 was also supported by a study where the pharmacological inhibition of Rock blocked the increase in NHE1 function in astrocytoma cells (44). These observations agree with the findings in the present study. Phosphorylation site mutation of either S703A or T653A resulted in a partial decrease in LPA-induced enhancement of Na+/H+ transport rate (Fig 4–6). Interestingly the Rsk site (S703) is within a predicted intrinsically disorder domain while T653 is upstream of the region possessing structural detail (12). The possible role of each phosphorylation site on structure of the C-terminal NHE domain could be unique but each result plays a critical role in regulating NHE1 transport.

We found that NHE1 phosphorylation by both Rock and Rsk kinase were critical for full LPA-induced activation of NHE1, and that loss of either site partially blocked the ability of LPA to stimulate proton efflux (Fig. 9). This validates our earlier work showing that LPA significantly induced an increase in pHi in quiescent cells; that LPA shifted the kinetic set point for transport by increasing the affinity for protons; and that both Rock and ERK signaling were required for full LPA-induced stimulation of NHE1 transport (29). This two-pathway-dependent activation of NHE1 was also observed after Gα12/13 activation of both ERK and RhoA/Rock pathways (18, 19). It is possible that the remaining LPA-induced proton transport observed in either NHE1 T653A or NHE1 S703A expressing cells could be due to the remaining phosphorylation site or due to another LPA-regulated kinase such as the direct phosphorylation of NHE1 by ERK (45). Similarly, growth factor stimulation of NHE1 involves ERK, Nck and a number of other kinases which could be responsible for the remaining NHE1 stimulation. These considerations appear to be ruled out by the experiments using the double mutant expressing cells (TSA). While residual LPA-inducible response was seen in singly mutated NHE1 expressing cells, the full LPA response was lost when both T653 and S703 phosphorylation sites were disrupted indicating that these two sites are critical for full agonist-stimulated NHE1 transport (Fig. 9). An unexpected outcome of these experiments was that the dual mutant NHE1 containing cell line showed a higher level of basal transport than resting wild-type cells. The implication of this observation is not clear but could indicate a yet undetermined level of regulation by phosphorylation. Taken together, this work supports our earlier observations that LPA utilizes both Rsk and Rock kinases to fully stimulate NHE1 transport and that the activity of the two phosphorylation sites is additive in nature and that these kinases signal independently of one another. While these data begin to clarify the mechanism of regulation of NHE1 transport in terms of LPA stimulation, the impact of other kinases identified to phosphorylate NHE1 needs to be elucidated and it remains to be determined whether there is a hierarchy of phosphorylation events that regulate transport activity.

Cell migration is a series of dynamic cytoskeletal rearrangements requiring NHE1 mediated proton transport and protein-protein interaction with the carboxyl terminus of NHE1 (35). NHE1 found in the lamellipodium ensures both a transmembrane and a transcellular pH gradient. The transmembrane pH gradient at the leading edge of migrating cells contributes to salt transport that drives local water movement into the cell impacting the outreach of microorganelles that are responsible for cell migration (6). The coordination of NHE1 effectors is diverse and we show here that both Rsk and Rock NHE1 phosphorylation sites are critical for cell motility and suggest that NHE1 phosphorylation uncouples motility events from cell growth (Fig. 11 & 12). Stress fiber formation induced by ezrin/radixin/moesin binding to NHE1 at the leading edge of migrating cells is dependent on receptor-mediated stimulation of both the ERK and RhoA signaling pathway (46). Thus, our initial hypothesis was that both the T653 and S703 phosphorylation sites would be critical for proton transport, stress fiber formation and cellular motility. Agonist induced formation of stress fibers is completely lost with either T653A or S703A mutations while these same cells retain a partial agonist-induced transport activation (Fig. 9 and 10). Interestingly, the same pattern was observed in cell motility where LPA-induced migration was totally abrogated with either phospho-NHE1 mutant (Fig. 10). Yet either mutation led to an increase in the level of proliferation (Fig. 11). The relationship between stress fibers and cell motility is not clear and dependent on cell typeFurther complicating the issue of the mechanism of NHE1-directed motility is the location and timing of these events. Rock is clearly an activator of NHE1 function and inhibition of RhoA or Rock decreases cell migration. NHE1 is located at the leading edge of migrating cells, yet RhoA and Rock are primarily assigned to the trailing edge of motile cells where RhoA and Rock act on the actomyosin contraction (47). The loss of cell motility when Rock is unable to phosphorylate NHE, as shown here, increases the support for RhoA and Rock having a second role coordinating cell polarity at the leading edge of the cell. This role is supported by a number of observations showing that RhoA, Rock and NHE1 play a key role in the leading edge of pseudopodia (48, 49).

In addition to supporting a direct role for Rock phosphorylation of NHE1, the early powerful work demonstrating that both proton transport and ERM proteins are critical for NHE1-directed cell migration is also supported by these data (35). However, as this work demonstrates the importance of both phosphorylation sites on NHE1 function, the role of the order and hierarchy of these and other phosphorylation events in the regulation of NHE1 remains unclear. For example, when Akt phosphorylates NHE1 expressed in PS120 fibroblasts, NHE1 is activated and actin stress fibers are disassembled (42). While a different Akt effect is observed in cardiac tissues where NHE1 transport is inhibited (50). Could the difference in Akt signaling be due to additional kinases or other regulatory mechanism(s) not yet studied? This highlights the need to understand the systematic regulation of NHE1 by phosphorylation and other factors.

Multiple possible mechanisms remain by which Rock phosphorylation can impact NHE1 activity. Both ERM and NHE1 are phosphorylated by Rock, however the NHE1-ERM binding site is significantly distal by 90–140 amino acids N terminal to the Rock phosphorylation site (Fig. 13). Does the phosphorylation of NHE1 by Rock influence ERM binding and regulation of NHE1 function? It is an attractive possibility as the same kinase phoshorylates ERM and NHE1, influences cytoskeletal formation and is critical for directed cell migration and invasion. A looping-out of the carboxyl-terminal domain of NHE1 has been observed with ERK-directed phosphorylation and could be similar to the Rock impact on ERM binding (3). Phosphorylation of NHE1 by Rsk within the intrinsic disorder domain could influence a higher ordered structure responsible for its activity. Another possibility of how Rock impacts NHE1 is that the Rock phosphorylation site lies in the middle of the high and low affinity calmodulinbinding domain (Fig 13). Rock phosphorylation could potentially alter calmodulin-NHE1 interaction. Finally T653 is only a few amino acids amino-terminal to the Akt phosphorylation site (S648). It would be interesting to see if the two sites work in parallel or in an antagonistic fashion on NHE1 function. The growing importance of the intrinsically disordered domain (aa 686–815) and the impact of phosphorylation in this region is undetermined but the role of phosphorylation in modulationg structure in this domain remains an interesting question. Therefore before we can gain a true comprehensive model of the impact of phosphorylation of NHE1, experiments will have to be conducted investigating each of the now identified phosphorylation sites, in a range of cell types with a diverse set of agonists. This is possible now that the Rock phosphorylation site has been defined with these studies.

Figure 13. Current model of NHE1 regulation at the C terminus.

NHE1-protein, other interactions and known phosphorylation sites are shown. Evidence of phosphorylation by kinases whose sites have not been determined are shown in the inset box.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Directed cell migration involves the sodium hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE1).

NHE1 is phosphorylated by Rock at serine 653.

Both Rsk and Rock cooperatively influence NHE1 transport and are critical for cell motility events.

Rock directly regulates both functions of NHE1 impacting lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) mediated cell motility

Both LPA signaling pathways equally contribute to NHE1 function.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NSF RUI MCB-0817784 and University of San Diego

Abbreviations

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- NHE1

sodium hydrogen exchanger isoform 1

- Rock

RhoA kinase

- RSK

ribosomal S6 kinase RSK

- ctNHE

C-Terminus Recombinant human NHE1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meima ME, Mackley JR, Barber DL. Beyond ion translocation: structural functions of the sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform-1. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007 Jul;16(4):365–372. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3281bd888d. PubMed PMID: 17565280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provost JJ, Wallert MA. Inside out: targeting NHE1 as an intracellular and extracellular regulator of cancer progression. Chemical biology & drug design. 2013 Jan;81(1):85–101. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12035. PubMed PMID: 23253131. Epub 2012/12/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Khan MF, Schriemer DC, Fliegel L. Structural changes in the C-terminal regulatory region of the Na/H exchanger mediate phosphorylation induced regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013 Apr 17; doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.007. PubMed PMID: 23602949. Epub 2013/04/23. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amith SR, Fliegel L. Regulation of the Na+/H+ Exchanger (NHE1) in Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013 Feb 15;73(4):1259–1264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4031. PubMed PMID:23393197. Epub 2013/02/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BL, Sykes BD, Fliegel L. Structural and functional insights into the cardiac Na(+)/H(+) exchanger. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012 Dec 7; doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.11.019. PubMed PMID:23220151. Epub 2012/12/12. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stock C, Schwab A. Protons make tumor cells move like clockwork. Pflugers Arch. 2009 Sep;458(5):981–992. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0677-8. PubMed PMID: 19437033. Epub 2009/05/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin C, Pedersen SF, Schwab A, Stock C. Intracellular pH gradients in migrating cells. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2011 Mar;300(3):C490–C195. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00280.2010. PubMed PMID: 21148407. Epub 2010/12/15. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauritzen G, Stock CM, Lemaire J, Lund SF, Jensen MF, Damsgaard B, et al. The Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1, but not the Na+, HCO3(−) cotransporter NBCn1, regulates motility of MCF7 breast cancer cells expressing constitutively active ErbB2. Cancer letters. 2012 Apr 28;317(2):172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.11.023. PubMed PMID: 22120673. Epub 2011/11/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reshkin SJ, Cardone RA, Harguindey S. Na+-H+ exchanger, pH regulation and cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013 Jan 1;8(1):85–99. doi: 10.2174/15748928130108. PubMed PMID: 22738122. Epub 2012/06/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen SF, Stock C. Ion channels and transporters in cancer: pathophysiology, regulation, and clinical potential. Cancer Res. 2013 Mar 15;73(6):1658–1661. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4188. PubMed PMID: 23302229. Epub 2013/01/11. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendus-Altenburger R, Kragelund BB, Pedersen SF. Structural dynamics and regulation of the mammalian SLC9A family of Na(+)/H(+) exchangers. Current topics in membranes. 2014;73:69–148. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800223-0.00002-5. PubMed PMID: 24745981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norholm AB, Hendus-Altenburger R, Bjerre G, Kjaergaard M, Pedersen SF, Kragelund BB. The intracellular distal tail of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 is intrinsically disordered: implications for NHE1 trafficking. Biochemistry. 2011 May 3;50(17):3469–3480. doi: 10.1021/bi1019989. PubMed PMID: 21425832. Epub 2011/03/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiese H, Gelis L, Wiese S, Reichenbach C, Jovancevic N, Osterloh M, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals the protein tyrosine kinase Pyk2 as a central effector of olfactory receptor signaling in prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Sep 9; doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.09.002. PubMed PMID: 25219547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moolenaar WH, van Meeteren LA, Giepmans BN. The ins and outs of lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Bioessays. 2004 Aug;26(8):870–881. doi: 10.1002/bies.20081. PubMed PMID: 15273989. Epub 2004/07/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiang SY, Dusaban SS, Brown JH. Lysophospholipid receptor activation of RhoA and lipid signaling pathways. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013 Jan;1831(1):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.004. PubMed PMID: 22986288. Epub 2012/09/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tominaga T, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Barber DL. p160ROCK mediates RhoA activation of Na-H exchange. Embo J. 1998;17(16):4712–4722. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tominaga T, Barber DL. Na-H exchange acts downstream of RhoA to regulate integrin-induced cell adhesion and spreading. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(8):2287–2303. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vexler ZS, Symons M, Barber DL. Activation of Na+-H+ exchange is necessary for RhoA-induced stress fiber formation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(37):22281–22284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooley R, Yu CY, Symons M, Barber DL. G alpha 13 stimulates Na+-H+ exchange through distinct Cdc42-dependent and RhoA-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(11):6152–6158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schofield AV, Bernard O. Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK) signaling and disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013 Apr 19; doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.786671. PubMed PMID: 23601011. Epub 2013/04/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellegrin S, Mellor H. Actin stress fibres. Journal of cell science. 2007 Oct 15;120(Pt 20):3491–3499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018473. PubMed PMID: 17928305. Epub 2007/10/12. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavet ME, Lehoux S, Berk BC. 14-3-3beta is a p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) isoform 1-binding protein that negatively regulates RSK kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003 May 16;278(20):18376–18383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208475200. PubMed PMID:12618428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehoux S, Abe J, Florian JA, Berk BC. 14-3-3 Binding to Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1 is associated with serum-dependent activation of Na+/H+ exchange. J Biol Chem. 2001 May 11;276(19):15794–15800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100410200. PubMed PMID: 11279064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi E, Abe J, Gallis B, Aebersold R, Spring DJ, Krebs EG, et al. p90(RSK) is a serum-stimulated Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1 kinase. Regulatory phosphorylation of serine 703 of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(29):20206–20214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucien F, Brochu-Gaudreau K, Arsenault D, Harper K, Dubois CM. Hypoxia-induced invadopodia formation involves activation of NHE-1 by the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK) PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028851. PubMed PMID: 22216126. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3246449. Epub 2012/01/05. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manhas N, Shi Y, Taunton J, Sun D. p90 activation contributes to cerebral ischemic damage via phosphorylation of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010 Sep 1;114(5):1476–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06868.x. PubMed PMID:20557427. Pubmed Central PMCID:2924815. Epub 2010/06/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avkiran M, Cook AR, Cuello F. Targeting Na+/H+ exchanger regulation for cardiac protection: a RSKy approach? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008 Apr;8(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.12.007. PubMed PMID: 18222727. Epub 2008/01/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallert MA, Thronson HL, Korpi NL, Olmschenk SM, McCoy AC, Funfar MR, et al. Two G protein-coupled receptors activate Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 in Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts through an ERK-dependent pathway. Cell Signal. 2005 Feb;17(2):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.07.004. PubMed PMID: 15494214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallert MA, Thronson HL, Korpi NL, Olmschenk SM, McCoy AC, Funfar MR, et al. Two G protein-coupled receptors activate Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 in Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts through an ERK-dependent pathway. Cellular signalling. 2005 Feb;17(2):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.07.004. PubMed PMID: 15494214. Epub 2004/10/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujisawa K, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Narumiya S. Identification of the Rho-binding domain of p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(38):23022–23028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa O, Fujisawa K, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Nakao K, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II, two isoforms of Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein serine/threonine kinase in mice. FEBS Lett. 1996;392(2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rath HM, Fee JA, Rhee SG, Silbert DF. Characterization of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C defects associated with thrombin-induced mitogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(6):3080–3087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rath HM, Doyle GA, Silbert DF. Hamster fibroblasts defective in thrombin-induced mitogenesis. A selection for mutants in phosphatidylinositol metabolism and other functions. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(23):13387–13390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sang RL, Johnson JF, Taves J, Nguyen C, Wallert MA, Provost JJ. alpha(1)-Adrenergic receptor stimulation of cell motility requires phospholipase D-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Chemical biology & drug design. 2007 Apr;69(4):240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00502.x. PubMed PMID: 17461971. Epub 2007/04/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denker SP, Barber DL. Cell migration requires both ion translocation and cytoskeletal anchoring by the Na-H exchanger NHE1. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(6):1087–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaty BT, Wang Y, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Sharma VP, Miskolci V, Hodgson L, et al. Talin regulates moesin-NHE-1 recruitment to invadopodia and promotes mammary tumor metastasis. J Cell Biol. 2014 Jun 9;205(5):737–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312046. PubMed PMID: 24891603. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4050723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taves J, Rastedt D, Canine J, Mork D, Wallert MA, Provost JJ. Sodium hydrogen exchanger and phospholipase D are required for alpha1-adrenergic receptor stimulation of metalloproteinase-9 and cellular invasion in CCL39 fibroblasts. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2008 Sep 1;477(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.007. PubMed PMID: 18539131. Epub 2008/06/10. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provost JJ, Rastedt D, Canine J, Ngyuen T, Haak A, Kutz C, et al. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor induced non-small cell lung cancer invasion and metastasis requires NHE1 transporter expression and transport activity. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2012 Jan 31; doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0068-y. PubMed PMID: 22290545. Epub 2012/02/01. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchan AM, Lin CY, Choi J, Barber DL. Somatostatin, acting at receptor subtype 1, inhibits Rho activity, the assembly of actin stress fibers, and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2002 Aug 9;277(32):28431–28438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201261200. PubMed PMID:12045195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin X, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Hooley R, Lin CY, Orlowski J, Barber DL. Galpha12 differentially regulates Na+-H+ exchanger isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(37):22604–22610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallert M, McCoy A, Voog J, Rastedt D, Taves-Patterson J, Korpi-Steiner N, et al. alpha-(1) adrenergic receptor-induced cytoskeletal organization and cell motility in CCL39 fibroblasts requires Phospholipase D1. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2011 Jun 15; doi: 10.1002/jcb.23227. PubMed PMID: 21678474. Epub 2011/06/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meima ME, Webb BA, Witkowska HE, Barber DL. The sodium-hydrogen exchanger NHE1 is an Akt substrate necessary for actin filament reorganization by growth factors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009 Sep 25;284(39):26666–26675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019448. PubMed PMID: 19622752. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2785354. Epub 2009/07/23. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karki P, Coccaro E, Fliegel L. Sustained intracellular acidosis activates the myocardial Na(+)/H(+) exchanger independent of amino acid Ser(703) and p90(rsk) Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010 Aug;1798(8):1565–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.05.005. PubMed PMID: 20471361. Epub 2010/05/18. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito M, Tanaka H, Sasaki M, Kurose H, Nakahata N. Involvement of aquaporin in thromboxane A2 receptor-mediated, G 12/13/RhoA/NHE-sensitive cell swelling in 1321N1 human astrocytoma cells. Cellular signalling. 2010 Jan;22(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.006. PubMed PMID: 19772916. Epub 2009/09/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malo ME, Li L, Fliegel L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger is mediated through phosphorylation of amino acids Ser770 and Ser771. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007 Mar 2;282(9):6292–6299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611073200. PubMed PMID: 17209041. Epub 2007/01/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K. Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010 Sep;67(9):545–554. doi: 10.1002/cm.20472. PubMed PMID: 20803696. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3038199. Epub 2010/08/31. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parri M, Chiarugi P. Rac and Rho GTPases in cancer cell motility control. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-23. PubMed PMID: 20822528. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2941746. Epub 2010/09/09. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cardone RA, Bagorda A, Bellizzi A, Busco G, Guerra L, Paradiso A, et al. Protein kinase A gating of a pseudopodial-located RhoA/ROCK/p38/NHE1 signal module regulates invasion in breast cancer cell lines. Molecular biology of the cell. 2005 Jul;16(7):3117–3127. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0945. PubMed PMID: 15843433. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1165397. Epub 2005/04/22. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heasman SJ, Carlin LM, Cox S, Ng T, Ridley AJ. Coordinated RhoA signaling at the leading edge and uropod is required for T cell transendothelial migration. The Journal of cell biology. 2010 Aug 23;190(4):553–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002067. PubMed PMID: 20733052. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2928012. Epub 2010/08/25. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snabaitis AK, Cuello F, Avkiran M. Protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylates and inhibits the cardiac Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. Circ Res. 2008 Oct 10;103(8):881–890. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175877. PubMed PMID: 18757828. Epub 2008/09/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.