Abstract

The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) is required for body weight homeostasis and normal gastrointestinal motility. However, the specific cell types expressing CB1R that regulate these physiological functions are unknown. CB1R is widely expressed, including in neurons of the parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system. The vagus nerve has been implicated in the regulation of several aspects of metabolism and energy balance (e.g., food intake and glucose balance), and gastrointestinal functions including motility. To directly test the relevance of CB1R in neurons of the vagus nerve on metabolic homeostasis and gastrointestinal motility, we generated and characterized mice lacking CB1R in afferent and efferent branches of the vagus nerve (Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice). On a chow or on a high-fat diet, Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice have similar body weight, food intake, energy expenditure, and glycemia compared with Cnr1flox/flox control mice. Also, fasting-induced hyperphagia and after acute or chronic pharmacological treatment with SR141716 [N-piperidino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-3-pyrazole carboxamide] (CB1R inverse agonist) paradigms, mutants display normal body weight and food intake. Interestingly, Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice have increased gastrointestinal motility compared with controls. These results unveil CB1R in the vagus nerve as a key component underlying normal gastrointestinal motility.

Introduction

The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1R) belongs to the endocannabinoid system (Matsuda et al., 1990; Piomelli, 2003) and is widely expressed in the mammalian body. In central and peripheral neurons, CB1R modulates neurotransmitter release (Marsicano and Lutz, 1999; Piomelli, 2003). Pharmacological blockade of CB1R reduces food intake and exerts anti-obesity effects in mice and humans and also improves lipid and glucose profiles of overweight and diabetic subjects (Ravinet Trillou et al., 2003; Després et al., 2005, 2006; Van Gaal et al., 2005; Addy et al., 2008). Deletion of CB1R in mice leads to reduced food intake, body adiposity, and increased insulin sensitivity (Cota et al., 2003; Ravinet Trillou et al., 2004). Interestingly, CB1R null mice are hypophagic after fasting and are insensitive to the anorectic actions of SR141716 [N-piperidino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-3-pyrazole carboxamide] (CB1R inverse agonist), suggesting that CB1R mediates the inhibitory effect of this drug on food intake (Di Marzo et al., 2001). In summary, CB1R exerts important functions on the control of body energy, glucose, and lipid balance.

The use of cell-specific CB1R genetic manipulation has indicated some of the critical sites in which CB1R regulates metabolic homeostasis. For example, CB1R in glutamatergic neurons has been reported to be required for the orexigenic effect of cannabinoids (Bellocchio et al., 2010). Also, CB1R in forebrain and sympathetic neurons has been shown to be required for normal energy expenditure (Quarta et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the role of CB1R in other neuronal sites, for example, the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, is yet to be known.

The CB1R also regulates gastrointestinal functions, for instance, motility. Of note, diarrhea is a frequent untoward side effect observed in patients treated with CB1R inverse agonist (Despres et al., 2005; Addy et al., 2008), and hypermotility of food through the intestines may reduce absorption of water and nutrients by the intestine and be an underlying cause of diarrhea. In rodents, inhibition of CB1R increases gastrointestinal motility, whereas activation of CB1R inhibits it (Colombo et al., 1998; Izzo et al., 1999; Landi et al., 2002; Pinto et al., 2002; Capasso et al., 2005). Also, CB1R null mice have increased gastrointestinal motility (Yuece et al., 2007). Moreover, it has been suggested that CB1R modulates acetylcholine release from myenteric neurons (Coutts and Pertwee, 1997; Coutts and Izzo, 2004).

Neurons of the vagus nerve have been shown to control body energy/glucose metabolism (Williams et al., 2000; Rossi et al., 2011) and upper gastrointestinal functions. CB1R is abundantly expressed in both vagal afferent and efferent neurons (Burdyga et al., 2004). Capsaicin deafferentation ablates the orexigenic effect of CB1R agonist (Gómez et al., 2002), and vagotomy impairs CB1R regulation of gastrointestinal motility (Krowicki et al., 1999). Thus, it has been suggested that CB1R in these neurons regulates feeding/body energy balance and gastrointestinal motility. To directly test these hypotheses, we generated and characterized mice lacking CB1R in vagal afferent and efferent neurons located in the nodose ganglia and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV).

Materials and Methods

Animal care.

Care of animals and all procedures were approved by University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in groups of four to five mice on a 12 h dark/light cycle with ad libitum access to water and food, unless otherwise specified. Mice were fed on a standard chow diet or, if mentioned, on a high-fat diet (TD88137; Harlan Teklad). All studies were performed using male mice.

Generation of Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice.

Mice containing a Cre-conditional Cnr1 null allele (Cnr1flox/wt) were generated in the laboratory of Pierre Chambon for Sanofi-Aventis and then imported by University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The targeting plasmid was constructed using genomic DNA of mouse strain 129/Sv. The single encoding exon of Cnr1 was flanked by loxP sites. The first loxP site was cloned upstream of Cnr1 start codon, and the loxP–FRT–Neomycin–FRT cassette was cloned downstream of Cnr1 stop codon. The targeting vector contained 2.1 kb of genomic DNA between loxP sites and 3.8 and 3 kb of genomic DNA as 5′ and 3′ homologous arms, respectively. The targeting plasmid was electroporated into 129 embryonic stem (ES) cells, and Neomycin-resistant clones were screened for homologous recombination as described below. Screening of 3′ end homologous recombination was performed by PCR using ES cell genomic DNA as template and the following primers: Neomycin forward (Neo F), AGGGGCTCGCGCCAGCCGAAGTGTT; and 3′ end reverse (3′ end R), ACAGCAGTCTCAATGATGCTACCAG. If ES cells contain a targeted allele, the expected PCR amplicon is ∼4 kb. Screening of 5′ end homologous recombination was performed by Southern blot using NheI as restriction enzyme and a probe between the 5′ end NheI site and the 5′ end edge of the construct. Expected bands are 12 kb (Cnr1 targeted) and 10 kb (Cnr1wt). Targeting was further confirmed by Southern blot in ES cell genomic DNA digested with restriction enzymes NheI or HindIII and a probe against the Neomycin cassette. Expected bands are 12 kb (NheI DNA fragment) and 7.2 kb (HindIII DNA fragment). Chimeric mice (F0) were bred to wild-type mice to generate mice bearing the targeted Cnr1 allele (F1). These F1 mutants were bred to a ubiquitously expressing FLPe recombinase (Flp) transgenic line. Successful removal of the flippase recognition target (FRT)-flanked phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK)–Neomycin cassette was confirmed by PCR in Cnr1flox/wt mice bearing a ubiquitously expressing Flp transgene (F2). These F2 mice were bred to wild-type mice, and offspring mice containing the FLP-recombined FRT-flanked PGK–Neomycin (F3) were selected by PCR genotyping. These F3 mutant mice were used to establish the Cre-conditional Cnr1 null line. Cnr1flox/flox mice were mated to Phox2b–Cre transgenic mice (line 1; Scott et al., 2011) to obtain the study groups that were in a mixed C57BL/6 and 129 genetic background. Mice were genotyped by PCR using primers CB1R forward (ACCACCTTCCTCATGTTAACCT) and CB1R reverse (GACCAGAGACAGCTCCAGA) for amplification of the Cnr1wt (197 bp) or Cnr1flox allele (247 bp) and CB1R forward and CB1R-D (GGGTAGTTAGGCTTCAGATTTGGA) for amplification of the Cre-recombined Cnr1 null allele (Cnr1Δ) (419 bp). Mice that underwent the “delta event,” which has been described previously (Balthasar et al., 2004), were excluded from the studies. To genotype for Phox2b–Cre allele, a PCR reaction was performed, as described previously (Scott et al., 2011), using the following primers: Phox2b forward, CCGTCTCCACATCCATCTTT; Phox2b reverse, GTACGGACTGCTCTGGTGGT; and Cre reverse, ATTCTCCCACCGTCACTACG. Male mice littermates were used for all the experiments performed.

In situ hybridization histochemistry.

Mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (500 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water 0.9% PBS, followed by 10% neutral buffered Formalin. Brains and nodose ganglion were dissected and placed in the same fixative for 4–6 h at 4°C, immersed in 20% sucrose in DEPC-treated PBS, pH 7.0, at 4°C for 24 h. Tissue was sliced into 25 μm sections on a freezing microtome. Sections from brain and nodose ganglion were mounted onto SuperFrost plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −20°C. Before hybridization, sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, cleared in xylene for 15 min, rehydrated in descending concentrations of ethanol, and placed in prewarmed 0.01 m sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Sections were pretreated for 10 min in a microwave, dehydrated in ethanol, and air dried. The CB1R riboprobe was generated by in vitro transcription with [35S]UTP. The 35S-labeled probe was diluted (106 dpm/ml) in hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 1× Denhardt's solution (Sigma). The hybridization solution (120 μl) was applied to each slide, and they were incubated overnight at 57°C. Sections were then treated with 0.002% RNAase A solution and submitted to stringency washes in decreasing concentrations of sodium chloride/SSC. Sections were dehydrated and enclosed in x-ray film cassettes with BMR-2 film (Eastman Kodak) for 48 h. Slides were dipped in NTB2 autoradiographic emulsion (Eastman Kodak), dried, and stored at 4°C for 14 d. Slides were developed with a D-19 developer (Eastman Kodak).

The CB1R probe (antisense) was transcribed from PCR fragments amplified using the following primers: forward, CTG CAA GAA GCT GCA ATC TG; and reverse, TGG CGA TCT TAA CAG TGC TC. This sequence is complementary to part of exon 2, which is the single encoding exon in Cnr1. Hybridization with the sense probe was performed as negative control.

Gastrointestinal motility.

Gastrointestinal motility was measured using the charcoal method as described previously (Rossi et al., 2003). Male mice at 10–12 weeks of age were fasted overnight with water ad libitum and received a single injection of vehicle or SR141716 (10 mg/kg, i.p.) at time 0. At 30 min, mice received 100 μl of a solution of 10% charcoal–5% Arabic gum in saline (Sigma-Aldrich) by oral gavage, and, at 50 min, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the intestine were quickly dissected. Immediately after dissection, the intestine was placed in cold 10% Formalin solution until the tissue was straightened, and the distance traveled by the solution was measured.

mRNA content.

Four-hour-fasted mice were killed, and stomach and small intestine were quickly dissected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until additional processing. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) following the protocol of the manufacturer. RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Roche Applied Science) and retro-transcribed using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). qPCR analysis was performed using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems).

Stool analysis.

Mice were individually housed, and stool samples were collected from the cages. Calorimetric and fat content analysis was performed by Central Analytical Lab, University of Arkansas Poultry Science, using ANSI/ASTM D2015-77 and AOAC 920.39C methods, respectively.

Body weight, metabolic rate, and food intake.

Body weight measurement was performed weekly starting at 5 weeks of age. Metabolic rate parameters (oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and respiratory exchange ratio) and food intake were measured by indirect calorimetry using the TSE labmaster system (TSE Systems). Approximately 8-week-old mice were transferred to the TSE labmaster system and allowed to acclimatize for 4 d, and data were collected for the following 3–4 d.

Pharmacological SR141716 treatment.

Single-housed 7- to 8-week-old mice were fasted for 24 h, and, right before the dark cycle, mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of vehicle or SR141716 (3 mg/kg). Food intake was measured for the following 2 h.

For chronic treatment with SR141716, mice were fed on high-fat diet for ∼8 weeks. Mice were single housed, and blood glucose, serum metabolites, and body composition were assessed before and after the pharmacological treatment. Blood glucose was measured using a standard glucometer (One Touch Ultra; Lifescan). Blood was centrifuged to collect serum for analysis of insulin (Crystal Chem), fatty acids (Wako Diagnostics), and triglycerides levels (Wako Diagnostics). Body composition was analyzed using the Echo MRI-100 system (Echo Medical Systems).

Data analyses.

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Analyses of the data were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired Student's t test or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test (**p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.01).

Results

Generation and validation of Phox2b–Cre; Cnr1flox/flox mice

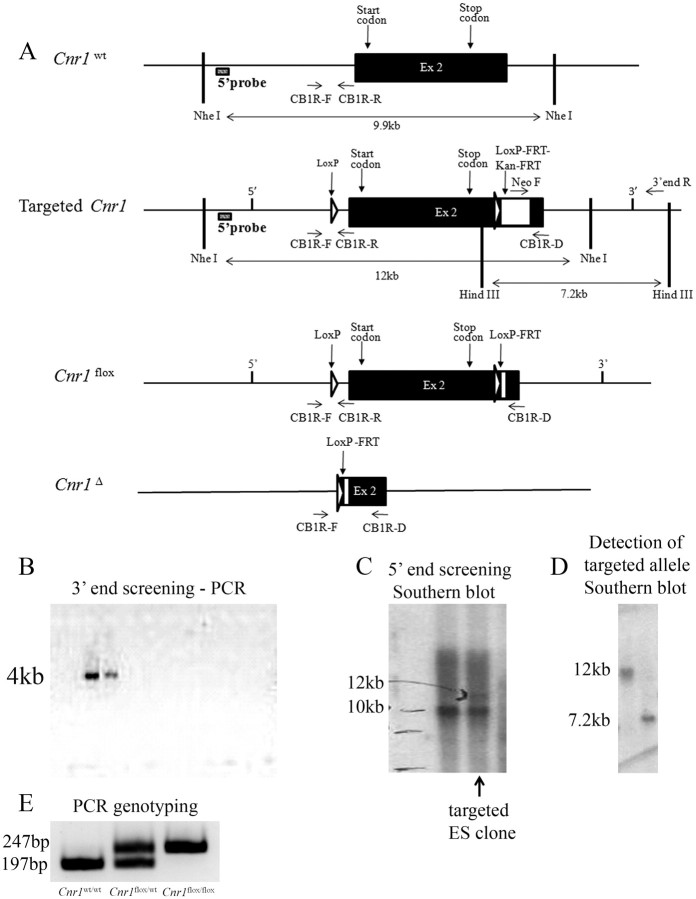

A Cre-conditional Cnr1 null allele (Cnr1flox) was generated by flanking exon 2 of Cnr1 allele with loxP sites (Fig. 1A). A 4 kb PCR amplicon was observed in two ES clones screened for homologous recombination at the 3′ end (Fig. 1B). In one of these clones, the two expected bands at 12 and 10 kb, from Cnr1 targeted and Cnr1wt allele, were detected by Southern blot (Fig. 1C). Additional analysis of this single clone by Southern blot allowed the detection of a 12 and 7.2 kb band in the DNA digested with the restriction enzymes NheI and HindIII, respectively (Fig. 1D). Cnr1flox/wt mice were mated, and Cnr1w/w, Cnr1flox/wt, and Cnr1flox/flox offspring were obtained at the expected ratio according to the Mendelian distribution of alleles (Fig. 1E). Cnr1flox/wt mice were crossed to Phox2b–Cre transgenic mice (Scott et al., 2011) to generate the study groups.

Figure 1.

Generation of mice bearing a Cre-conditional Cnr1 null allele (Cnr1flox/wt). Schematic representation of the targeting strategy. Represented are Cnr1wt, targeted Cnr1, Cnr1flox, and Cnr1Δ alleles (A). Screening of 3′ end homologous recombination by PCR. A 4 kb PCR amplicon expected in ES cells bearing Cnr1 targeted allele (B). Screening of 5′ end homologous recombination by Southern blot using NheI as the restriction enzyme and a probe upstream of 5′ edge of the construct. Expected 12 kb (Cnr1 targeted) and 10 kb (Cnr1 wt) bands are indicated (C). Detection of the Cnr1 targeted sequences in the single clone deemed targeted according to B and C (D). NheI and HindIII were the restriction enzymes used on left and right lanes, respectively, and the probe was against the Neomycin cassette (D). Expected PCR amplicons from tail genomic DNA of Cnr1w/w, Cnr1flox/wt, and Cnr1flox/flox mice (E).

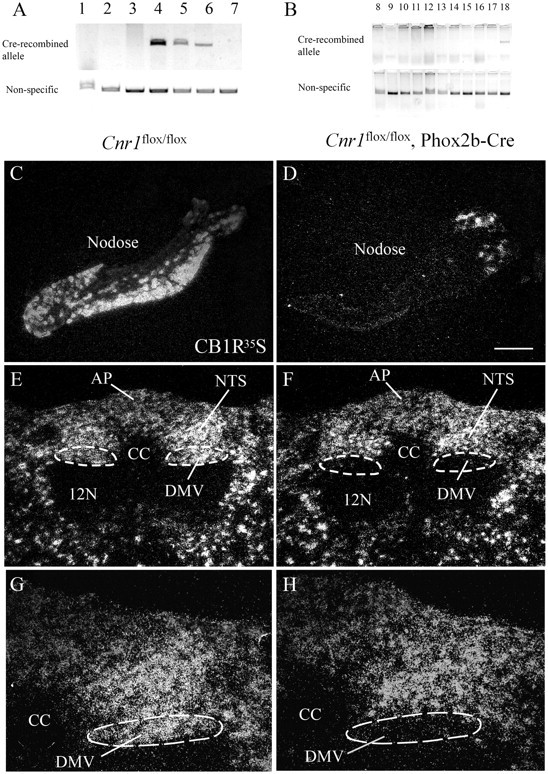

To determine whether Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice have Cre-recombined Cnr1 allele in Phox2b neurons, we first performed PCR assays using genomic DNA from different brain areas and different organs/tissues. The Cre-recombined Cnr1 allele is present in midbrain, hindbrain, and nodose ganglia (Fig. 2A), all sites in which Phox2b neurons are located. Cre-recombined Cnr1 allele was not detected in all other tissues tested, including the stomach, different parts of the small intestine, and colon (Fig. 2B). Second, we performed in situ hybridization histochemistry to detect Cnr1 mRNA in brain tissue. In Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice, distribution of Cnr1 mRNA was similar to the pattern observed in Cnr1flox/flox mice, including parabrachial nucleus (data not shown) and nucleus of the solitary tract (Fig. 2E–H). However, Cnr1 mRNA was not detected in great part of nodose ganglia and DMV (Fig. 2C–H). Thus, these results show that Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice lack CB1R in nodose ganglia and DMV neurons.

Figure 2.

Deletion of CB1R in nodose and DMV neurons. Detection of Cre-recombined Cnr1 null allele by PCR using genomic DNA of a Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mouse [A: 1, forebrain; 2, hypothalamus; 3, pituitary; 4, midbrain; 5, hindbrain; 6, nodose; 7, tail as negative control; B: 8, heart; 9, kidney; 10, stomach; 11, duodenum; 12, jejunum; 13, ileum; 14, colon; 15, pancreas; 16, liver; 17, perigonadal white adipose tissue; 18, positive control, hindbrain]. In situ hybridization histochemistry for Cnr1 mRNA (in situ probe complementary to Cnr1 exon 2) in nodose and hindbrain sections of Cnr1flox/flox (C, E, G) and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre (D, F, H) male mouse. Scale bar: C–F, 200 μm; G, H, 100 μm. AP, Area postrema; 12N, 12 nerve; CC, central canal; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract.

Body weight homeostasis in Phox2b–Cre; Cnr1flox/flox mice

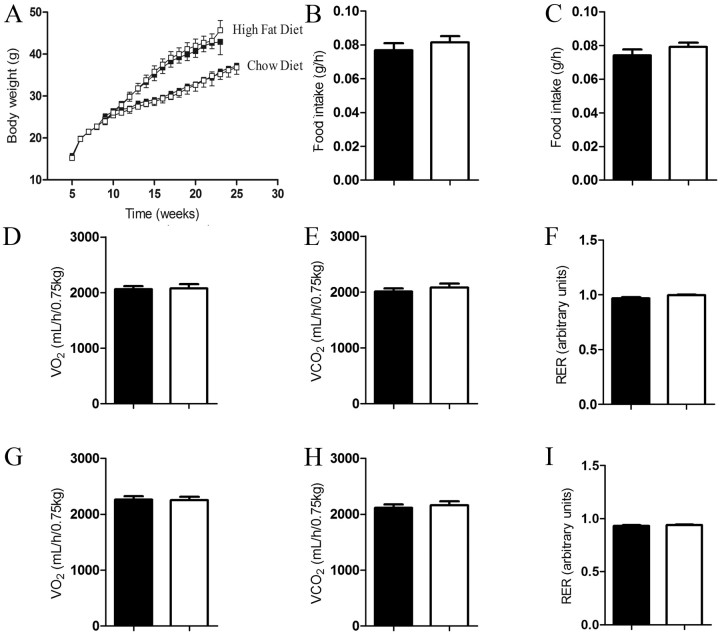

CB1R controls food intake, energy expenditure, and thus body weight homeostasis (Cota, 2007; Quarta et al., 2010). To test whether CB1R in the nodose/DMV is required for body weight homeostasis, we measured body weight, food intake, and energy expenditure in mice lacking CB1R in the nodose/DMV neurons. On chow or high-fat diet feeding regimens, Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice have similar body weight compared with Cnr1flox/flox controls (Fig. 3A). Food intake, oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and respiratory exchange ratio were also similar between Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre and Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 3B–I).

Figure 3.

CB1R in nodose and DVM neurons does not regulate body energy balance. Body weight curve of standard chow or high-fat fed mice (A) (chow diet: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 7 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 7; high-fat diet: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 13 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 16). Food intake of mice fed on standard chow (B) or high-fat diet (C). Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and respiratory exchange ratio of mice fed on chow (D–F) or high-fat diet (G–I) (chow diet: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 13 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 13; high-fat diet: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 12 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 12). Filled black symbols/bars and open symbols/bars represent Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice, respectively. Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student's t test.

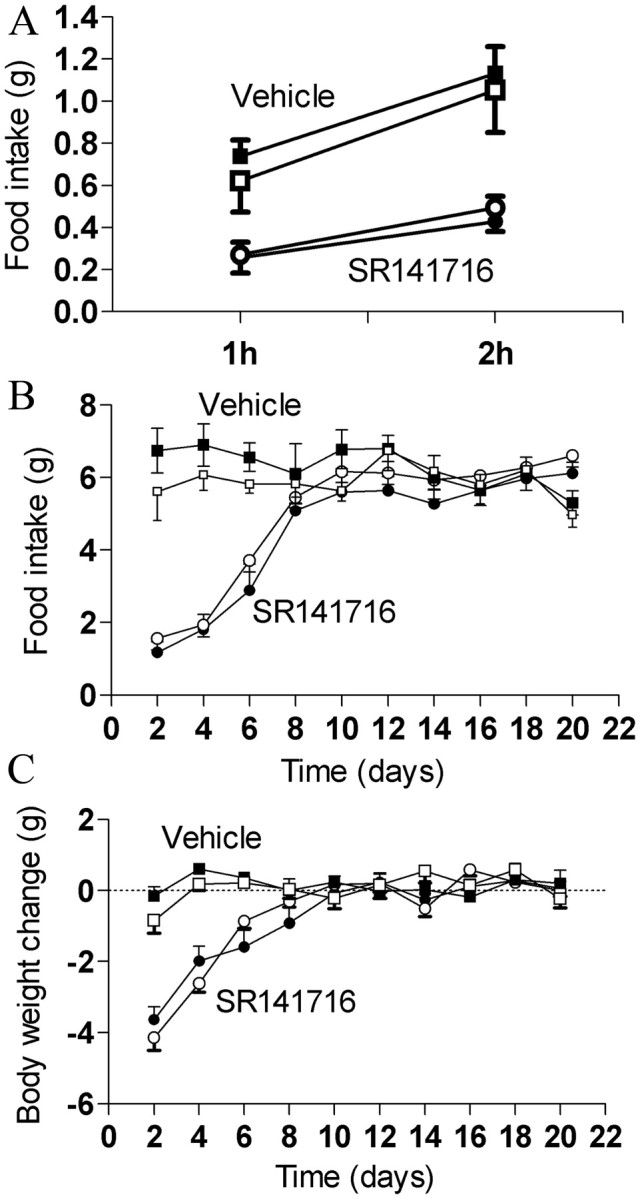

CB1R also regulates fasting-induced hyperphagia and mediates the anorexigenic effect of SR141716 (Di Marzo et al., 2001). Thus, we tested whether CB1R in the nodose/DMV neurons is required for normal fasting-induced hyperphagia. Food intake after 24 h fasting was also similar between Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice (Fig. 4A). SR141716-treated Cnr1flox/flox mice significantly reduce food intake compared with vehicle-treated Cnr1flox/flox mice, similar to previously reported results (Fig. 4A) (Di Marzo et al., 2001). The anorexigenic effect of SR141716 in Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice was similar to the effect observed in Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, SR141716-treated Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice tended to have longer meals and reduced rate of food intake compared with Cnr1flox/flox mice, but the differences between the groups were not statistically significant (data not shown). In the chronic SR141716 treatment study, Cnr1flox/flox mice treated with SR141716 had reduced food intake during approximately the first week compared with vehicle-treated Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 4B). The anorexigenic effect of SR141716 was transient as reported previously (Ravinet Trillou et al., 2003; Cota et al., 2009). Also, body weight reduction was observed in SR141716-treated compared with vehicle-treated Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 4C). In Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice, the anorexigenic and body weight reducing effects of SR141716 were similar to those observed in Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 4B,C). Fed and fasted blood glucose, fatty acids, and triglycerides were similar between Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice either before treatment or after treatment (data not shown). As for body composition analysis, fat mass was reduced in SR141716-treated compared with vehicle-treated Cnr1flox/flox mice, but similar fat mass was observed in Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre compared with Cnr1flox/flox mice, either before or after treatment (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggest that CB1R in the nodose/DMV neurons is not required to control body weight, food intake, energy expenditure, blood glucose, fatty acids, triglycerides, and fat mass and to mediate the effects of SR141716 on these parameters.

Figure 4.

CB1R in nodose and DVM neurons is not required for the anorexigenic effect and anti-obesity effect of SR141716. Fasting-induced hyperphagia (A) of mice fed on chow diet. Food intake (B) and body weight (C) curves of mice fed on high-fat diet and treated with 10 mg/kg SR141716 or vehicle (vehicle treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 6 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 7; SR141716 treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 8 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 10). Mice received daily intraperitoneal injections right before the beginning of dark cycle. Symbols represent Cnr1flox/flox (filled) and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre (open). Results are expressed as means ± SEM.

Gastrointestinal motility in Phox2b–Cre; Cnr1flox/flox mice

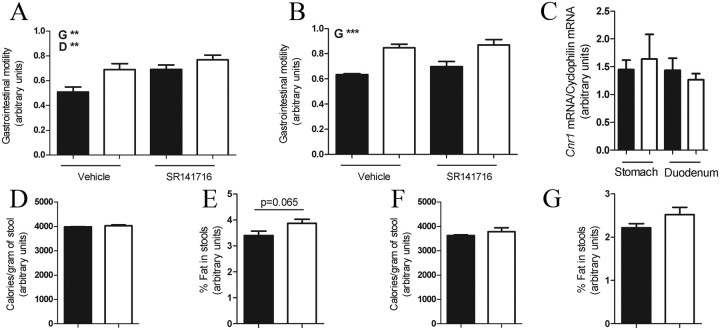

Pharmacological administration of CB1R antagonist (SR141716) or genetic deletion of CB1R in mice increases gastrointestinal motility (Coutts and Izzo, 2004; Yuece et al., 2007). In vitro data suggest that CB1R in cholinergic fibers of the parasympathetic branch neurons mediate this effect (Coutts and Pertwee, 1997; Coutts and Izzo, 2004). However, the CB1R-expressing sites that mediate this effect are unknown. Here we tested whether CB1R in nodose/DMV neurons is required to regulate gastrointestinal motility. On chow diet, Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice had increased gastrointestinal motility compared with Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 5A). Also, SR141716-treated mice had increased gastrointestinal motility compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that CB1R in nodose/DMV neurons is required for normal gastrointestinal motility in chow diet feeding conditions.

Figure 5.

CB1R in nodose and DMV neurons is required for gastrointestinal motility. Gastrointestinal motility in vehicle- or SR141716-treated mice fed on standard chow (A) (vehicle treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 10 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 10; SR141716 treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 9 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 9) or high fat (B) (vehicle treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 6 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 6; SR141716 treated: Cnr1flox/flox, n = 7 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 7). qPCR analysis of stomach and duodenum total mRNA (Cnr1flox/flox, n = 5 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 5) (C). Calorimetric analyses or percentage of fat content of stools of mice fed on standard chow (D, E) or high fat (F, G) (Cnr1flox/flox, n = 6 and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre, n = 6). Bars represent Cnr1flox/flox (filled) and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre (open). Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA (A, B) or Student's t test (C–G). For A, genotype (G), F(1,31) = 8.6, p < 0.05; drug (D), F(1,31) = 8.9, p < 0.05; and interaction, F(1,31) = 1.3, p = 0.25. For B, genotype (G), F(1,17) = 23.3, p < 0.05; drug, F(1,17) = 1.16, p = 0.29; and interaction, F(1,17) = 0.3, p = 0.61.

High-fat diet increases gastrointestinal motility (Izzo et al., 2009). Thus, we investigated the relevance of CB1R in nodose/DMV neurons on regulation of gastrointestinal motility in the context of high-fat diet. On high-fat diet, Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice had increased gastrointestinal motility compared with Cnr1flox/flox mice (Fig. 5B), but this parameter was not affected by SR141716 treatment in both genotypes (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that CB1R in nodose/DMV neurons is required for normal gastrointestinal motility also in the high-fat diet feeding condition.

To exclude the possibility that the increase in gastrointestinal motility observed in Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre was a result of the transgene per se, we performed experiments using Cnr1w/w; Phox2b–Cre and Cnr1w/w mice fed on chow diet. We observed similar gastrointestinal motility in both groups (data not shown), indicating that the increase in gastrointestinal motility in Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre results from deletion of CB1R in Phox2b neurons and not by an effect attributable to the Phox2b–Cre transgene itself.

CB1R is expressed in several neurons of the small intestine, and the majority of those are cholinergic (Coutts et al., 2002). To investigate whether the phenotype on gastrointestinal motility could be a result of reduced Cnr1 mRNA expression in the stomach or small intestine, we measured Cnr1 mRNA levels in those tissues. In either the stomach or duodenum, similar levels of Cnr1 mRNA was detected in samples from Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice (Fig. 5C). Thus, these results indicate that the phenotype on gastrointestinal motility is not the result of reduced Cnr1 mRNA expression in the stomach or small intestine.

To further investigate whether increased gastrointestinal motility would result in reduced absorption of nutrients, we performed calorimetric and fat content analysis in the stools. Similar calories per gram or fat content was observed in stools of Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice fed on chow diet (Fig. 5D,E). Of note, fat content tended to be higher in stools of Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice, but differences were not statistically significant. Also, similar calories per gram or fat content was observed in Cnr1flox/flox and Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice fed on a high-fat diet (Fig. 5F,G). Therefore, these data suggest that increased gastrointestinal motility does not lead to reduced absorption of nutrients, a result that is in agreement with the unchanged energy balance of Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice.

Discussion

CB1R is widely expressed and regulates several physiological processes. Genetic deletion studies have demonstrated that CB1R regulates body weight and gastrointestinal motility; nevertheless, the sites mediating these actions remain to be identified. Several results show that the vagus nerve controls aspects of energy metabolism, including food intake and blood glucose homeostasis (Williams et al., 2000; Fan et al., 2004; Rossi et al., 2011). Moreover, CB1R in the vagus nerve has been suggested as an important molecule underlying normal feeding and consequentially body weight homeostasis. By using the Cre/loxP system, we generated mice lacking CB1R in afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) vagal neurons. Notably, deletion of CB1R expression in vagal neurons did not significantly alter energy balance regulation or glucose homeostasis. In contrast, we found that CB1R expressed by Phox2b neurons is required for the regulation by CB1R of gastrointestinal motility.

SR141716 was considered a promising pharmacological drug for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. However, because of its psychotropic effect (increased depression), the process of additional development of this drug was halted (Di Marzo, 2008). However, the concurrent effects of CB1R inverse agonist on mood and body weight may be separated if the CB1R sites governing mood and body weight were to be identified. Thus, it is of interest to identify the sites expressing CB1R that regulate energy balance in an attempt to dissociate the beneficial effects of SR141716 on body weight reduction from its psychiatric side effect. Notably, if CB1R expressed by the nodose/DMV neurons is relevant for control of body energy metabolism, it would represent a possible target for brain-impermeable CB1R inverse agonist anti-obesity drugs. However, our data support the view that CB1R in those neurons are not required for regulation of body energy balance, and, as such, these sites should be ruled out as potential targets for development of anti-obesity CB1R inverse agonist drugs.

Diarrhea is a frequent side effect reported by patients treated with SR141716 (Van Gaal et al., 2005; Addy et al., 2008). Indeed, this is a common side effect of anti-obesity drugs (Cahoon, 2010), and increase in gastrointestinal motility is one underlying cause of diarrhea. Importantly, despite the discomfort that it may generate, alteration in gastrointestinal motility is often observed in gastrointestinal diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome (prevalence of 9–23% worldwide according to the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders) and may lead to severe consequences, such as inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Several studies indicate that CB1R controls gastrointestinal motility; nevertheless, the neurons that express CB1R that mediate it are unclear. It has been suggested that CB1R acts to control acetylcholine release from neurons of the myenteric neurons (Coutts and Pertwee, 1997). CB1R colocalizes with several cholinergic neurons of the enteric nervous system (Coutts et al., 2002), but we do not observe deletion of Cnr1 mRNA in the duodenum and stomach of Cnr1flox/flox; Phox2b–Cre mice. Indeed, it has been reported previously that the Phox2b–Cre transgenic line used in this study does not express the transgene in the enteric nervous system (Ferreira-Gomes et al., 2011). The transgenic Phox2b–Cre mouse line used in this study has been reported to express Cre in a few other sites in addition to the nodose/DMV (Rossi et al., 2011), but we do not believe that these sites contribute to the phenotype observed because they have not been suggested previously to regulate gastrointestinal motility. Our results suggest that CB1R in the nodose/DMV is required for control of gastrointestinal motility.

Anandamide levels increase during fasting in small intestine, and it has been suggested that it is a metabolic cue signaling through the vagal circuitry to stimulate feeding (Gómez et al., 2002). Conversely, given the fact that during fasting there is no major need of motility to have the food traveling through the digestive tract, it is plausible that anandamide may serve as a cue to suppress gastrointestinal motility.

Footnotes

Data presented in this paper were supported by Sanofi-Aventis, National Institutes of Health Grant RL1DK081185 (J.K.E.), the American Diabetes Association (J.K.E.), the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (J.R.), the Academy of Finland (J.R.), and the Finnish Cultural Foundation (J.R.). We thank Charlotte E. Lee and Syann Lee for technical support and Roberto Coppari for suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript. We thank Laura Brule, Mi Kim, Danielle Lauzon, and Linh-An Cao and the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Core at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (supported by National Institutes of Health Grants PL1 DK081182 and UL1RR024923.

References

- Addy C, Wright H, Van Laere K, Gantz I, Erondu N, Musser BJ, Lu K, Yuan J, Sanabria-Bohórquez SM, Stoch A, Stevens C, Fong TM, De Lepeleire I, Cilissen C, Cote J, Rosko K, Gendrano IN, 3rd, Nguyen AM, Gumbiner B, Rothenberg P, et al. The acyclic CB1R inverse agonist taranabant mediates weight loss by increasing energy expenditure and decreasing caloric intake. Cell Metab. 2008;7:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua SC, Jr, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio L, Lafenêtre P, Cannich A, Cota D, Puente N, Grandes P, Chaouloff F, Piazza PV, Marsicano G. Bimodal control of stimulated food intake by the endocannabinoid system. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:281–283. doi: 10.1038/nn.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga G, Lal S, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Expression of cannabinoid CB1 receptors by vagal afferent neurons is inhibited by cholecystokinin. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2708–2715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5404-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon L. Companies throw their weight behind new antiobesity drugs. Nat Med. 2010;16:136. doi: 10.1038/nm0210-136a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso R, Matias I, Lutz B, Borrelli F, Capasso F, Marsicano G, Mascolo N, Petrosino S, Monory K, Valenti M, Di Marzo V, Izzo AA. Fatty acid amide hydrolase controls mouse intestinal motility in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:941–951. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo G, Agabio R, Lobina C, Reali R, Gessa GL. Cannabinoid modulation of intestinal propulsion in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;344:67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D. CB1 receptors: emerging evidence for central and peripheral mechanisms that regulate energy balance, metabolism, and cardiovascular health. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23:507–517. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Marsicano G, Tschöp M, Grübler Y, Flachskamm C, Schubert M, Auer D, Yassouridis A, Thöne-Reineke C, Ortmann S, Tomassoni F, Cervino C, Nisoli E, Linthorst AC, Pasquali R, Lutz B, Stalla GK, Pagotto U. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:423–431. doi: 10.1172/JCI17725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Sandoval DA, Olivieri M, Prodi E, D'Alessio DA, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Obici S. Food intake-independent effects of CB1 antagonism on glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1641–1645. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutts AA, Izzo AA. The gastrointestinal pharmacology of cannabinoids: an update. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutts AA, Pertwee RG. Inhibition by cannabinoid receptor agonists of acetylcholine release from the guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1557–1566. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutts AA, Irving AJ, Mackie K, Pertwee RG, Anavi-Goffer S. Localisation of cannabinoid CB(1) receptor immunoreactivity in the guinea pig and rat myenteric plexus. J Comp Neurol. 2002;448:410–422. doi: 10.1002/cne.10270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimonabant in Obesity-Lipids Study Group. Després JP, Golay A, Sjöström L. Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N Eng J Med. 2005;353:2121–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després JP, Lemieux I, Alméras N. Contribution of CB1 blockade to the management of high-risk abdominal obesity. Int J Obesity (Lond) 2006;30(Suppl 1):S44–S52. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V. CB(1) receptor antagonism: biological basis for metabolic effects. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:1026–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Liu J, Bátkai S, Járai Z, Fezza F, Miura GI, Palmiter RD, Sugiura T, Kunos G. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature. 2001;410:822–825. doi: 10.1038/35071088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Ellacott KL, Halatchev IG, Takahashi K, Yu P, Cone RD. Cholecystokinin-mediated suppression of feeding involves the brainstem melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nn1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Gomes MS, González-Lebrero RM, de la Fuente MC, Strehler EE, Rossi RC, Rossi JP. Calcium occlusion in plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32018–32025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez R, Navarro M, Ferrer B, Trigo JM, Bilbao A, Del Arco I, Cippitelli A, Nava F, Piomelli D, Rodríguez de Fonseca F. A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor-dependent modulation of feeding. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9612–9617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo AA, Mascolo N, Pinto L, Capasso R, Capasso F. The role of cannabinoid receptors in intestinal motility, defaecation and diarrhoea in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;384:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo AA, Piscitelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Romano B, Borrelli F, Petrosino S, Di Marzo V. Peripheral endocannabinoid dysregulation in obesity: relation to intestinal motility and energy processing induced by food deprivation and re-feeding. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krowicki ZK, Moerschbaecher JM, Winsauer PJ, Digavalli SV, Hornby PJ. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits gastric motility in the rat through cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;371:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M, Croci T, Rinaldi-Carmona M, Maffrand JP, Le Fur G, Manara L. Modulation of gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit in rats through intestinal cannabinoid CB(1) receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;450:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4213–4225. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto L, Izzo AA, Cascio MG, Bisogno T, Hospodar-Scott K, Brown DR, Mascolo N, Di Marzo V, Capasso F. Endocannabinoids as physiological regulators of colonic propulsion in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:227–234. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–884. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta C, Bellocchio L, Mancini G, Mazza R, Cervino C, Braulke LJ, Fekete C, Latorre R, Nanni C, Bucci M, Clemens LE, Heldmaier G, Watanabe M, Leste-Lassere T, Maitre M, Tedesco L, Fanelli F, Reuss S, Klaus S, Srivastava RK, et al. CB(1) signaling in forebrain and sympathetic neurons is a key determinant of endocannabinoid actions on energy balance. Cell Metab. 2010;11:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinet Trillou C, Arnone M, Delgorge C, Gonalons N, Keane P, Maffrand JP, Soubrie P. Anti-obesity effect of SR141716, a CB1 receptor antagonist, in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00545.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinet Trillou C, Delgorge C, Menet C, Arnone M, Soubri é P. CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:640–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi J, Herzig KH, Võikar V, Hiltunen PH, Segerstråle M, Airaksinen MS. Alimentary tract innervation deficits and dysfunction in mice lacking GDNF family receptor alpha2. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:707–716. doi: 10.1172/JCI17995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi J, Balthasar N, Olson D, Scott M, Berglund E, Lee CE, Choi MJ, Lauzon D, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. Melanocortin-4 receptors expressed by cholinergic neurons regulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011;13:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Williams KW, Rossi J, Lee CE, Elmquist JK. Leptin receptor expression in hindbrain Glp-1 neurons regulates food intake and energy balance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2413–2421. doi: 10.1172/JCI43703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIO-Europe Study Group. Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rössner S. Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet. 2005;365:1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66374-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DL, Kaplan JM, Grill HJ. The role of the dorsal vagal complex and the vagus nerve in feeding effects of melanocortin-3/4 receptor stimulation. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1332–1337. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuece B, Sibaev A, Broedl UC, Marsicano G, Göke B, Lutz B, Allescher HD, Storr M. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor modulates intestinal propulsion by an attenuation of intestinal motor responses within the myenteric part of the peristaltic reflex. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:744–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]