Abstract

Background

Several studies have shown that lipid-lowering therapy to address hypercholesterolemia is generally inadequate because the target cholesterol goal is not achieved. Our study reviews the cholesterol goal attainment among patients receiving lipid lowering therapy in Indonesian hypercholesterolemic patients.

Methods

This surveywas part of the Pan-Asian CEPHEUS (CEntralized Pan-Asian survey on tHE Under-treatment of hypercholeSterolemia) study, involving hypercholesterolemic patients ≥ 18 years of age, who were on lipid- lowering treatment for ≥ 3 months. Lipid concentrations were measured, demographic and other clinically relevant information were collected. Definitions and criteria set by the updated 2004 National Cholesterol Education Program – Adult Treatment Program III was applied.

Results

In this survey, 149 physicians enrolled 979 patients, of whom only 834 were included in the final analysis. The mean age was 56.5 years, 53.5% male, and 82.3% were on statin monotherapy. The LDL-C goal attainment rate amongst Indonesians (31.3%)was belowthat of the overall Asian rate (49.1%). The lowest attainment (12.1%)was found in patients with a therapeutic target < 70 mg/dL. Additionally, the goal attainment rate in patients with metabolic syndrome (28%) was significantly lower than in patients without metabolic syndrome (37.5%, p = 0.006). Goal attainment was inversely related to cardiovascular risk and baseline LDL-C (p < 0.001). It was also noted that approximately 65.1% of patients believed he/she could miss a dosage without affecting his/her blood cholesterol concentration.

Conclusions

High proportions of Indonesian hypercholesterolemic patients on lipid-lowering drug are not at the recommended LDL-C levels, and remain at risk for cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Dyslipidemia, Hypercholesterolemia, Indonesian, LDL cholesterol

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease related mortality and disability can be prevented by adequate management of the risk factors, including hypercholesterolemia. With this in mind, cholesterol treatment goals for hypercholesterolemic patients have been established through cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines.1-3

Data from various prevention clinical trials have shown that reducing low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) conjunction with a proper statin regimen in high cardiovascular risk patients significantly reduces morbidity and mortality.4 Cholesterol level reduction could lower the risk of recurrent coronary events and delayed atherosclerotic progression among patients with coronary heart disease or other atherosclerotic disease. Despite the fact that therapeutic targets have been established by industry guidelines, and effective therapeutic regimens are available, there was still an inordinate number of patients who did not receive appropriate and optimal therapy and thus failed to achieve the target cholesterol levels. In the previous report from the CEPHEUS (CEntralized Pan-survey on tHE Under-treatment of hypercholeSterolemia) in Europe, Asia and South Africa, arround 40-60% of patients who underwent cholesterol-reducing therapy reached the targeted lipid lowering goals as recommended by Third Joint European Task Force.5-8 In this study, we aimed to report about the percentage of patients under treatment for hypercholesterolemia in the Indoneasian population, and to identify positive and negative determinants which suggest whether these patients may or may not achieve LDL-C targets. The study also provided the characteristics of those patients and physicians that were studied, as well as the attitudes of these two groups towards the management of hypercholesterolemia.

METHODS

Our study was a subset of the CEPHEUS Pan-Asian study and only included results associated with the Indonesian population. The study was a prospective, cross-sectional survey of subjects on lipid-lowering pharmacological therapy. The CEPHEUS Pan-Asian survey was conducted at 405 sites in Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Hong Kong SAR, and China, with a target enrollment of approximately 8000 patients. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Investigational Review Board and the Ethics Committee governing each participating centre before the commencement of patient enrollment. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of good clinical research practice, and conformed to ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All participating patients provided written informed consent before being enrolled in the study.

Study population

Study subjects were patients who fulfilled the following criteria: (i) aged ≥ 18 years, (ii) had ≥ 2 cardiovascular risk factors as defined by the updated 2004 NCEP ATP III guidelines,9 and (iii) had, at the time of enrollment, been on lipid-lowering drugs for at least 3 months, with no dose exchange for at least 6 weeks. Patients were excluded if they were found to have participated in any interventional clinical study during the preceding 90-day period, were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, or were personally involved in the conduct of this study.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to determine the proportion of patients on lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment attaining LDL-C goals, as defined by the updated 2004 NCEP ATP III guidelines. The secondary objectives of the study included: (i) determining the proportion of patients in primary or secondary prevention; with metabolic syndrome (definition of metabolic syndrome was obtained from the criteria of ATP III, but the waist circumference was modified to apply to Asia population; > 90 cm for male and > 80 cm for female)10 who attained LDL-C goals; (ii) identifying the determinants of under treatment of hypercholesterolemia; and (iii) investigating patient and physician characteristics associated with the allocation of treatment approaches. For all purposes, definitions and criteria set by the updated 2004 NCEP ATP III guidelines were applied.

Survey instruments and procedure

The survey instrument consisted of a questionnaire for both the attending physician and the patient, and a case record form (CRF) for the physician to record the patient’s demographic, results of physical examination, cardiovascular medical history, known cardiovascular risk factors [including coronary heart disease (CHD) or CHD risk equivalents and metabolic syndrome], past lipid profile (if any), current lipid-lowering therapy, and reason for the treatment. The physician questionnaire was comprised of 23 questions designed to collect information on the physician’s awareness and use of practice guidelines, therapeutic LDL-C goals adopted, their management of hypercholesterolemia, and related communications with patients, as well as personal attitudes pertinent to hypercholesterolemia and its management. The patient questionnaire also consisted of 17 questions designed to find out the patient’s perception of hypercholesterolemia and its management, their compliance with lipid-lowering treatment, and personal satisfaction with the treatment.

When the study was commenced, each physicianinvestigator first completed the physician questionnaire. Consenting patients were then consecutively enrolled and assessed. Each participating patient completed the patient questionnaire before they underwent the assessment. On assessment, each patient’s data were entered into the individual CRF. An overnight fasting blood sample was taken for determination of blood glucose and lipid concentrations (total cholesterol, LDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides). The biochemical analysis was performed at the local laboratory in individual hospitals. The cardiovascular risk profile of each patient was determined based on criteria set by the updated 2004 NCEP ATP III guidelines.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was LDL-C goal attainment, defined as the recommended proportion of patients (overall) on lipid-lowering treatment achieving their respective therapeutic LDL-C goals. The secondary endpoint was LDL-C goal attainment rate in primary and secondary prevention patients, and in those with metabolic syndrome. Additional study endpoints included the percentage of patients in different CHD risk groups achieving LDL-C goals, attainment of LDL-C goals according to individual CHD risk factors, LDL-C goal attainment according to lipid-lowering drug type, determinants of lipid-lowering drug prescription and goal attainment, and follow-up treatment of patients not achieving LDL-C targets.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was performed on the 834 patients who completed the study, and whose attending physicians completed and returned the physician’s questionnaires. Descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions, medians, means and standard deviations, were used to describe demographics data, and anthropometric measurements such as body weight, height, and waist circumference, and concentrations of total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C and triglycerides. Exploratory analysis was done to determine factors affecting achievement of LDL-C goals in individual patients. Factors to be identified were grouped into two categories: patient determinants and physician determinants. For patients, these included the 17 questions on the patient questionnaire, metabolic syndrome (yes/no) and individual components including blood pressure (yes/no); risk category and whether or not fulfilling a very high-risk category; type of therapy (statin or other monotherapy or combination therapy); previous lipid profile (i.e. total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C and triglyceride levels before treatment); duration since drug initiation (years); and reason for prescribing current lipid-lowering drugs (primary prevention, secondary prevention, familial hypercholesterolemia). For physicians, these included the 23 questions on the physician questionnaire, physician age (continuous variable), gender, years of practice (continuous variable), and specialization (general practitioner/GP, cardiologist, endocrinologist, other).

Patient factors were screened in a univariate analysis by means of logistic model analysis, and physician factors were screened in a univariate analysis by means of generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis with a random effect of the physician using the NLMIXED procedure of the SAS system. In these univariate analysis, the response variable was the achievement of LDL-C goals in individual patients, and patient or physician factors were examined one at a time as an exploratory variable. The factors that proved to be significant (p < 0.01) in the univariate analysis were then further evaluated in a multivariate analysis by means of GLMM approach for their possible association with the outcome (attainment of the set LDL-C goal). This significance level, which is stricter than that used conventionally, was used in order to avoid choosing meaningless variables that may result from the very large number of patients included in the data. Factors were chosen and added to the model one by one at each step until no factors with a p-value < 0.01 remained. For the final models, the following results were provided; regression coefficient estimate, standard error and p-value for each effect, and estimated odds ratio (OR) with associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

The association between the follow-up plan when patients were not at treatment goal and the potential predictor variables (patient determinants) for the primary endpoint was evaluated. For categorical variables, cross-tables were produced. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were calculated for each category of the follow-up plan.

RESULTS

Physician-investigator characteristics

A total of 149 physician-investigators returned the physician survey questionnaire. Overall, their mean age was 47.1 years, 60.5% were males, and they had been in practice for a mean of 17.8 years. Most were general practitioners (65.8%). Individual cholesterol targets were set for a mean of 81.8% for their patients. Nearly all the physicians (96.6%) stated that they used LDL-C levels as the laboratory measure for the treatment target. About 66.1% of physicians indicated that they used NCEP ATP III (Framingham) to establish the therapeutic target. Table 1 shows characteristics of physicians who conducted the survey investigations in Indonesia.

Table 1. Demographic and characteristics of physician-investigator.

| Physician Characteristics (N = 149) | Values |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47.1 (10.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 89 (60.5) |

| Female | 58 (39.5) |

| Duration of practice (years), mean (SD) | 17.8 (10.6) |

| Type of practice, n (%) | |

| General practitioner/primary care physician | 98 (65.8) |

| Cardiologist | 16 (10.7) |

| Endocrinologist | 0 (0) |

| Other | 35 (23.5) |

| Percentage of patients with individual cholesterol target set (%), mean (SD) | 81.8 (24.5) |

| Lipid used for treatment target, n (%) | |

| Total cholesterol | 137 (91.9) |

| LDL cholesterol | 144 (96.6) |

| HDL cholesterol | 134 (89.9) |

| Triglyceride | 133 (89.3) |

| Used guidelines to establish therapeutic targets, n (%) | |

| Yes | 122 (84.1) |

| No | 23 (15.9) |

| Specified guidelines used (multiple choice), n (%) | |

| NCEP ATP III (FRAMINGHAM) | 72 (66.1) |

| National guidelines | 32 (29.4) |

| Local guidelines/recommendation | 11 (10.1) |

| Joint European guidelines (SCORE) | 10 (9.2) |

| Individual practice guidelines/recommendation | 10 (9.2) |

| Other | 8 (7.3) |

| Unable to name the precise guidelines used | 4 (3.7) |

| Unknown | 40 |

Patient characteristics

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics, including primary diagnosis, CHD risk categories, and compliance with lipid-lowering therapy are shown in Table 2. The mean age of patients was 56.5 years and 53.5% were males. The most common CHD risk factors were hypertension (75.9%) and age (men ≥ 45 years, women ≥ 55 years; 75.7%). About 39.2% of patients had diabetes, 35.3% had CHD, 19.6% had multiple risk factors with 10-year risk for CHD > 20%, and 64.2% had metabolic syndrome. The percentages of traditional factors for metabolic syndrome were central abdominal obesity (70.2%), raised triglyceride level (60%), reduced HDL cholesterol (44.4%), raised blood pressure (69.5%), and raised fasting plasma glucose (43.8%). The patients’ responses in the survey questionnaires reflected generally poor compliance with drug treatment, with 56.3% patients sometimes forgetting to take their tablets, and 22.2% forgetting to take their tablets at least once a week (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients.

| Baseline Characteristic (N = 834) | Values |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 56.5 (11.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 446 (53.5) |

| Female | 388 (46.5) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.5 (4.2) |

| Abdominal obesity, mean (SD) | 91.4 (11.2) |

| Blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | |

| Systolic | 138.3 (19.0) |

| Diastolic | 86.2 (10.2) |

| CHD risk factors, n (%) | |

| Smoking | 206 (24.8) |

| Hypertension | 630 (75.9) |

| Low HDL-C | 260 (32.0) |

| Family history of premature CHD | 358 (43.0) |

| Age (men ≥ 45 years, women ≥ 55 years) | 624 (75.7) |

| High HDL-C (negative risk factor) | 67 (8.4) |

| CHD or CHD risk equivalents, n (%) | |

| CHD | 289 (35.3) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 98 (12.2) |

| Carotid arterial disease | 63 (7.9) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 17 (2.1) |

| Diabetes | 320 (39.2) |

| Multiple risk factors with 10-year CHD risk > 20% | 145 (19.6) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 508 (64.2) |

| Sometimes forget to take tablets, n (%) | |

| Agree | 463 (56.3) |

| Disagree | 345 (42.0) |

| Don’t know/can’t remember | 14 (1.7) |

| Frequency of forgetting to take tablets, n (%) | |

| > once a week | 135 (22.2) |

| Once a week | 101 (16.6) |

| Once a month/less than a month | 179 (29.5) |

| Unknown | 192 (31.6) |

Indications and drugs for lipid-lowering therapy

Patients’ therapeutic LDL-C goals were stratified based on the NCEP ATP III: 34.9% of the population fulfilled the criteria for the very high-risk category, while 37.4% were considered high risk. Thus 72.3% of patients overall had their LDL-C goal set at < 100 mg/dL. Indications for lipid-lowering therapy were primary prevention in 63.5% of patients, and secondary prevention in 29.6% patients (Table 3). The mean duration of treatment was 1.3 years. About 56% of patients were still taking the same lipid-lowering drug first prescribed for them, and 12.5% were taking the same drug with an increased dose.

Table 3. LDL-C goals and lipid-lowering drug treatments of patients.

| Treatment Result (N = 834) | Values |

| LDL-C goal according to 2004 NCEP ATP III, n (%) | |

| < 70 mg/dL (very high risk)a | 290 (34.9) |

| < 100 mg/dL (high risk)b | 311 (37.4) |

| 130 mg/dL (moderate risk)c | 226 (27.2) |

| 160 mg/dL (low risk)d | 5 (0.6) |

| Duration of lipid-lowering treatment (years), mean (SD) | 1.3 (2.3) |

| Reason for lipid-lowering treatment, n (%) | |

| Primary prevention | 478 (63.5) |

| Secondary prevention | 223 (29.6) |

| Familial hypercholesterolemia | 52 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 81 (9.7) |

| Treatment changes since initiation of lipid-lowering therapy, n (%) | |

| Same drug | 462 (56.0) |

| Same drug at increased dose | 103 (12.5) |

| Changed once or twice (maybe including additional of other drug) | 245 (29.7) |

| Changed several times (maybe including additional of other drug) | 15 (1.8) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.1) |

| Monotherapy, n (%)e | 724 (87.3) |

| Statin | 682 (82.3) |

| Rosuvastatin | 202 (27.9) |

| Atorvastatin | 139 (19.2) |

| Simvastatin | 310 (42.8) |

| Other statin (fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin) | 31 (4.3) |

| Fibrat | 41 (5.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

| Combination therapy, n (%)f | 105 (12.7) |

| Statin with statin | 4 (3) |

| Statin with fibrates | 87 (82.8) |

| Statin with others | 13 (12.4) |

| Other combination | 1 (0.9) |

a Very high risk patient {patients with presence of established CVD plus one or more of the following: multiple major risk factors [especially diabetes], severe and poorly controlled risk factors [especially continued cigarette smoking], or multiple risk factors of the metabolic syndrome [especially high triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL plus non-HDL-C ≥ 130 mg/dL with low HDL-C (≥ 40 mg/dL)]; or patients with acute coronary syndromes}. b High risk patient [CHD or CHD risk equivalents (10-year risk > 20%)]. c Moderately high risk [2 + risk factors (10-year risk 10-20%)] or moderate risk patient [2 + risk factors (10-year risk < 10%)]. d Low risk patient (0-1 risk factor). e The percentage of patients on monotherapy was the percentage of 724 patients in lipid-lowering monotherapy. f The percentage of patients on combination theraphy was the percentage of 105 patients in lipid-lowering combination therapy.

Among patients on monotherapy, 82.3% were on statin monotherapy, and the most commonly used statin in drug monotherapy was simvastatin (42.8%), followed by rosuvastatin (27.9%) and atorvastatin (19.2%). The most frequently prescribed daily dosage for monotherapy was < 20 mg for simvastatin (32.3%) and 10 mg for rosuvastatin (22.1%). Very few patients were on other classes of lipid-lowering drugs, whether used as monotherapy or in combination with statins or other drugs.

Changes in lipid levels with lipid-lowering therapy

The available last known lipid profile in patients before they underwent lipid-lowering drug treatment, mean (standard deviation) total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations in patients were 241.0 ± 50.6 mg/dL (n = 652), 153.1 ± 39.7 mg/dL (n = 622), 45.0 ± 11.5 mg/dL (n = 597) and 204.4 ± 129.4 mg/dL (n = 645) respectively. And for our patients, the lipid profile after participating in this study was 196.2 ± 45.3 mg/dL (n = 831), 123.0 ± 37.7 mg/dL (n = 834), 47.8 ± 12.0 mg/dL (n = 826) and 159.7 ± 82.2 mg/dL (n = 832) for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglyceride, respectively.

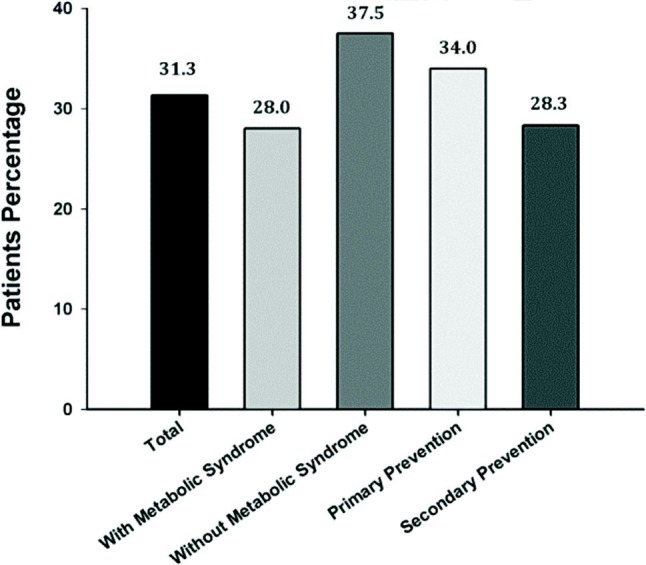

LDL-C goal attainment

Of 833 patients whose lipid levels were determined during the study, 31.3% achieved their LDL-C goal (Figure 1). The rate of LDL-C goal attainment in patients with metabolic syndrome was only 28% compared with 37.5% in patients without metabolic syndrome. In primary and secondary prevention patients the rate of LDL-C goal attainment was similar (34.0% and 28.3%).

Figure 1.

Overall LDL-C goal attainment among patients with or without metabolic syndrome, and patients with primary or secondary prevention (per-protocol population).

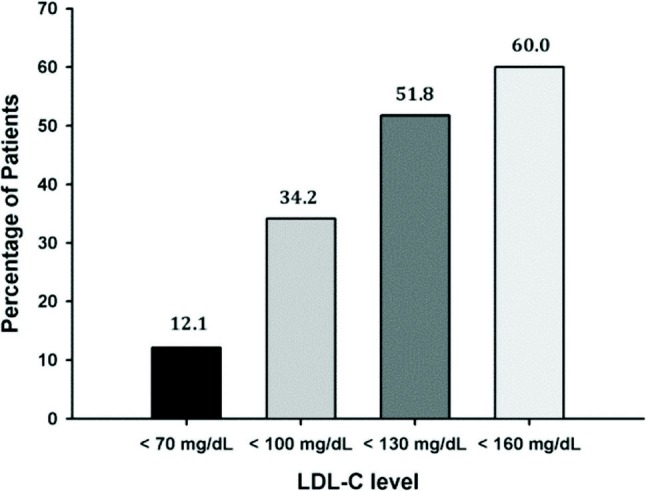

The proportion of patients attaining their respective LDL-C goal decreased with increasing cardiovascular risk level (Figure 2). About 51.8% and 60.0% patients with low and moderate risk attained their LDL-C goal; meanwhile only 12.1% patients with very high risk achieved their goals.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients attaining their LDL-C goals according the updated 2004 NCEP ATP III (per protocol population).

Attainment of LDL-C goal according to age, gender and various CHD risk categories is summarized in Table 4. Compared to other age groups, a higher proportion of patients aged < 40 years attained their therapeutic LDL-C goals, meanwhile the rate of LDL-C attainment was similar between male and female patients. Overall, LDL-C goal attainment in patients without CHD or CHD risk equivalent was higher than in patients with CHD or CHD risk equivalent. Furthermore, factors that correlated significantly to the LDL-C attainement was presented in Table 5. The high risk and very high risk patients were the most difficult to attain the LDL-C goal.

Table 4. LDL-C goal attainment according to age, gender and CHD risk category (per protocol population).

| Patients Characteristic | N (%) achieving LDL-C goal | p value |

| Age (years) | 0.012 | |

| < 40 | 25 (51.0) | |

| 40-54 | 87 (28.5) | |

| 55-69 | 111 (29.8) | |

| ≥ 70 | 38 (35.8) | |

| Gender | 0.002 | |

| Male | 160 (35.9) | |

| Female | 101 (26.1) | |

| Body mass index | 0.147 | |

| Normal | 97 (31.9) | |

| Overweight | 131 (33.5) | |

| Obese | 33 (24.4) | |

| Abdominal obesity, yes/no* | 176 (30.6)/82 (33.5) | 0.42 |

| Triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL, yes/no | 138 (28.8)/116 (36.3) | 0.027 |

| CHD or CHD risk equivalent | ||

| CHD, yes/no | 54 (18.7)/201 (38.0) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, yes/no | 15 (15.3)/238 (33.8) | < 0.001 |

| Carotid arterial disease, yes/no | 6 (9.5)/246 (33.4) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, yes/no | 73 (22.9)/184 (37.1) | < 0.001 |

| Multiple risk factors with 10-year risk | 32 (22.1)/207 (34.8) | < 0.004 |

Percentage based on per protocol population. * Abdominal obesity was confirmed if waist circumference men > 90 cm; women > 80 cm. CHD, coronary heart disease.

Table 5. Factors that significantly relate to LDL-C goal attainment (per protocol population).

| Variable | Class | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| LDL-C goal | 100 mg/dL vs. 70 mg/dL | 3.8 | 2.48-5.78 | < 0.001 |

| 130 mg/dL vs. 70 mg/dL | 7.8 | 05.04-12.13 | < 0.001 | |

| 160 mg/dL vs. 70 mg/dL | 10.9 | 01.76-67.68 | < 0.001 | |

| Total cholesterol level before treatment* | 0.9 | 0.99-0.99 | < 0.001 | |

| LDL-C level before treatment* | 0.9 | 0.99-0.99 | < 0.001 | |

| PQ15: current situation according patient’s opinion** | < 0.001 | |||

| Cholesterol goal not achieved | 0.75 | 0.41-1.39 | ||

| Not sure whether has achieved cholesterol target | 1.22 | 0.70-2.12 | ||

| Has achieved cholesterol target | 3.71 | 2.19-6.27 | ||

| PQ16: patient’s feelings about his/her hypercholesterolemia treatment† | < 0.001 | |||

| Satisfied | 2.43 | 1.60-3.71 | ||

| Motivated | 0.92 | 0.57-1.47 |

* The number was the total number of patients in FAS, not including unknown data; **The percentage was based on the total number of answers in FAS, not including unknown data. OR, odds ratio.

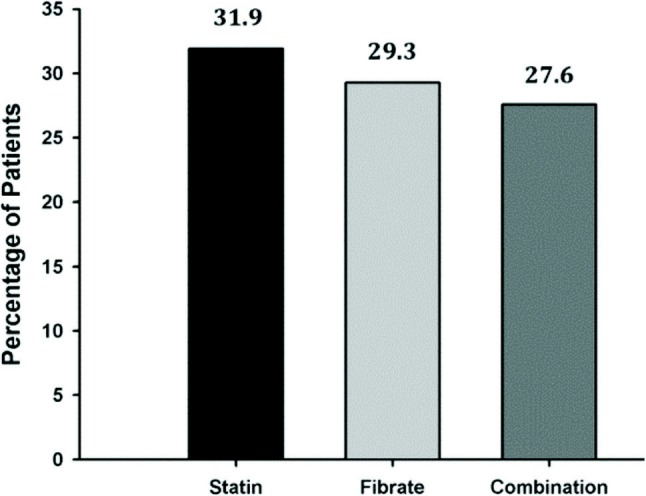

Therapeutic target attainment in obese patients (24.4%) was lower than in normal patients (31.9%). Figure 3 shows the proportion of patients on various lipidlowering drug therapies attaining their LDL-C goal. Patients who were on statins as monotherapy had a higher LDL-C goal attainment rate (31.9%) compared with other classes of drug as monotheraphy (29.3%) or as combination theraphy (27.6%). The attainment of LDL-C goals with the different type of statin and fibrate treatment was presented in Table 6. The result showed that treatment with rosuvastatin, atrovastatin and gemfibrozil gained a net positive attainment of LDL-C goals compared to the mean attainment of LDL-C goals (31.3%) according to 2004 updated NCEP ATP III guidelines.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients attaining their LDL-C goal according lipid-lowering drug therapy.

Table 6. The achievement of LDL-C goals according to different type of statin and fibrate treatment.

| Treatment | Total patients on target, N (%) | Total patients not on target, N (%) |

| Statin monotherapy | ||

| Rosuvastatin | 77 (38.3) | 124 (61.7) |

| Atorvastatin | 51 (36.7) | 88 (66.3) |

| Fluvastatin | 1 (25) | 3 (75) |

| Lovastatin | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) |

| Pravastatin | 3 (15.8) | 16 (84.2) |

| Simvastatin | 84 (27.1) | 226 (72.9) |

| Fibrate monotheraphy | ||

| Fenofibrate | 7 (25) | 21 (75) |

| Gemfibrozil | 11 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) |

| Combination therapy | 29 (27.6) | 76 (72.4) |

Determinants of drug prescription and LDL-C goal attainment

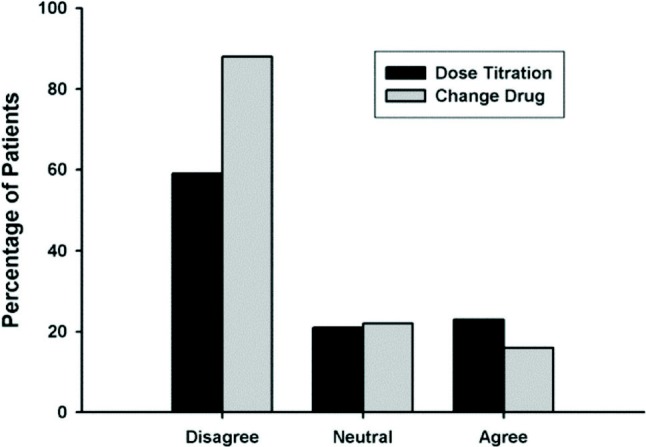

Drug prescription was influenced by the physicianrelated factor regarding dose titration and drug changing (Figure 4). Determination of treatment allocation (statin or non-statin) was significantly influenced by triglyceride concentration before treatment (95% CI; 0.99-1.00; p < 0.001). LDL-C goal, total cholesterol and LDL-C concentrations before treatment significantly correlated with LDL-C goal attainment. CHD or CHD risk equivalent (peripheral arterial disease, carotid arterial disease, diabetes) also significantly influenced the cholesterol goal attainment (p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Doctors’ opinion regarding dose titration and drug changing.

Other factors which also significantly influenced goal attainment were patient opinion about the existing medical situation, as well as patient opinion about his/her hypercholesterolemia treatment.

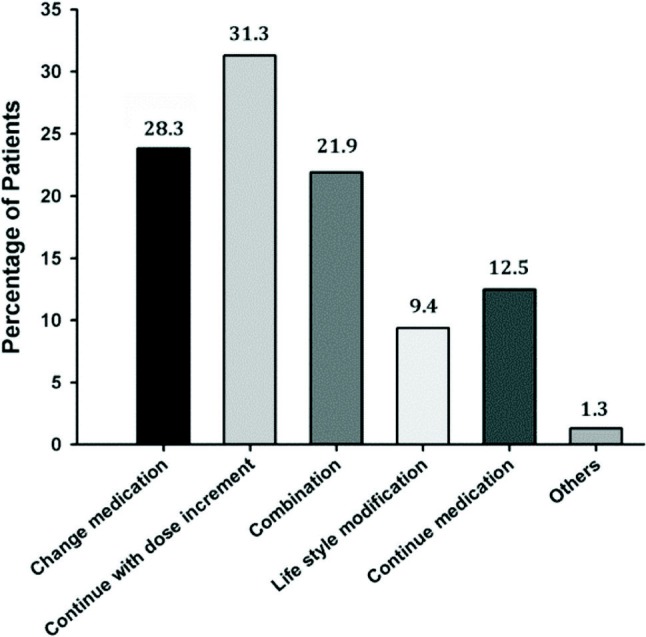

Follow-up treatment of patients not attaining target LDL-C level

Follow-up treatment was provided to 160 patients whose LDL-C levels were established to be short of their therapeutic goal (Figure 5). The proportion of patients ≥ 70 years of age who had their existing drug medication switched and had their existing dose increased was higher than patients < 70 years of age. Additionally, patients with the following risk profiles also had their existing medication increased: CHD risk factor (smoking 32.3%, hypertension 29.8%, low LDL-C 31.0%, family history with premature CHD 31.8%, age 32.5%), CHD risk equivalent (diabetes 38.1%), metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity 32.7%, triglyceride > 150 mg/dL 33.7%), patients fulfilling the criteria of very high-risk patients (33.8%), lipid-lowering treatment (primary prevention 29.1%, secondary prevention 41.8%), and statin monotherapy (35.2%).

Figure 5.

Follow-up treatment in patients not achieving LDL-C targets (n = 160 evaluated).

DISCUSSION

The key observation from this study is that a substantial proportion of hypercholesterolemic patients in Indonesia were not attaining their therapeutic cholesterol goals. Only 31.3% of the patient cohort attained the LDL-C goal according to the 2004 update NCEP ATP III guidelines. At the time of survey, about 72.3% patients were in the very high and high risk category with an LDL-C goal of < 70 mg/dL and < 100 mg/dL, respectively. Despite having been on lipid-lowering treatment for a mean duration of 1.3 ± 2.3 years, the LDL-C goal attainment of this group remained low which were 12.1% and 34.2% respectively.

There were several factors which might suggest why the LDL-C goal attainment percentage was low in our country. These factors included patient awareness and compliance, physician factors, drug therapy and reimbursement system. There were 50.4% of patients who stopped taking medication when cholesterol returned to normal, and 56.3% of patients sometimes forgot (22.2% more than once a week) to take a tablet; more than half of patients were still on the same lipid-lowering drug as first prescribed and only 12.5% had increased their dose. From the physician factors, 65.8% of the physicians were general practioners and only 84.1% of the physician used guidelines to establish therapeutic targets. And there was a trend that more patients of general practitioners were not attaining the LDL-C goal when compared to patients of the specialists (cardiologist/endocrinologist/others). Meanwhile the proportion of physicians using NCEP ATP III (Framingham) guidelines to establish patient’s therapeutic cholesterol goal was lower when compared to other countries in the Pan Asia CEPHEUS study. The national guideline was more lenient in targeting the LDL-C goal when compared to the NCEP ATP III guideline. Furthermore, 42.8% used the lipid lowering drug simvastatin, of which 75.5% of them took simvastatin in doses < 20 mg. In the meta-analysis from VOYAGER, the study showed that simvastatin in 10 mg doses resulted in decrement of LDL-C only about 27% from baseline which was the lowest when compared to the other statin treatment.11 The decision to use simvastatin might be related to the lowest price that could be afforded by most of the patients, since the reimbusement system in our country did not pay for or reimburse this cost.

The efficacy of lipid lowering treatment, and more particularly of statins, as both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular risk to develop atherosclerosis has been accepted the world thoughout. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that the beneficial effect of statin will remained even after discontinuation of the drugs.12,13 In addition, the overall benefits observed with statins appear to be greater than what might be expected from changes in the lipid levels alone, and the impact on atheroma plaques seems convincing.14-16 The rate of LDL-C goal attainment was higher in patients receiving statin monotherapy compared with other treatments (31.9% vs. 29.3%). This was in concordance with the findings from the Pan-European CEPHEUS study which showed that compared to other drug treatments, statin therapy resulted in the highest rate of LDL-C goal attainment (56.6% vs. 37.6% for fibrates and 19.4% for other types of lipid-lowering drugs). In addition to patient-related factors (including patients’ compliance with their lipid-lowering treatment), the low rate of LDL-C target attainment also influenced by the physician’s opinion regarding dose titration and drug switching. About 58.5% and 88.6% of physicians disagree with dose titration and drug switching.

Our study result provided a useful overview of current hypercholesterolemic management and treatment outcomes in Indonesia, which reflected that hypercholesterolemic management was still suboptimal. It obviously needs improvement in terms of monitoring, treatment, including combination therapy and dose titration, patient compliance, and lifestyle counseling. Physician education and incentivization maybe addressed by some of the physician-related factors. Although poor lipid goal attainment is a complex problem, good coorperation between the government and the medical community might provide a better solution. We currently set up for the updated national guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular, sporadic campaign of lowering cholesterol awareness, and deliver education to the primary physician. In the future, our government has set up for national reimbursement system which will be applied widely in 2014.

LIMITATION

There were several limitations in this study. The study population was small and there was variability in the practice environment. Participating physicians and patients were not selected randomly so that the study population may not be representative of the target population. In addition, the population included only hypercholesterolemic patients who were already on some form of lipid-lowering medication. We also did not collect information on dietary and other lifestyle interventions, adverse events, nor on the socio-economic status of the patients, which might co-determine treatment compliance and LDL-C goal attainment in patients.

CONCLUSIONS

A large proportion of hypercholesterolemic patients on lipid-lowering treatment in Indonesia are not at their recommended therapeutic LDL-C levels. Most of these patients are at a high or very high cardiovascular risk. Consequently, hypercholesterolemia treatment should be optimized in order to maximize the benefit and improve treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank all trial participants, physicians, nurses, and practices who contributed to the CEPHEUS Indonesia study. The study was supported by one principal funding source, AstraZeneca Indonesia. We also thank Anna Dewiyana (UBM Medica – Medidata Indonesia – funded by AstraZeneca Indonesia), who was responsibile for typing and collating the report.

FUNDING

This work was supported by AstraZeneca Indonesia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Muhammad Munawar and Sodiqur Rifqi received a research grant from AstraZeneca and research grant from Pfizer. Beny Hartono had nothing to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:1423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone NJ, Bilek S, Rosenbaum S. Recent National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III update: adjustments and options. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:53E–59E. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter DA, Manuel DG, Gunraj N, et al. Age, risk-benefit trade-offs, and the projected effects of evidence-based therapies. Am J Med. 2004;116:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans MP, Castro Cabezas M, Strandberg T, et al. Centralized Pan-European survey on the under-treatment of hypercholesterolaemia (CEPHEUS): overall findings from eight countries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:445–454. doi: 10.1185/03007990903500565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermans MP, Van Mieghem W, Vandenhoven G, Vissers E. Centralized Pan-European survey on the undertreatment of hypercholesterolaemia (CEPHEUS) Acta Cardiol. 2009;64:177–185. doi: 10.2143/AC.64.2.2035341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JE, Chiang CE, Munawar M, et al. Lipid-lowering treatment in hypercholesterolaemic patients:the CEPHEUS Pan-Asian survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1741826710397100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raal F, Schamroth C, Blom D, et al. CEPHEUS SA: a South African survey on the undertreatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011;22:234–240. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr., Cleeman JI, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome:Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholls SJ, Brandrup-Wognsen G, Palmer M, Barter PJ. Metaanalysis of comparative efficacy of increasing dose of atorvastatin versus rosuvastatin versus simvastatin on lowering levels of atherogenic lipids (from VOYAGER) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.08.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen TR, Wilhelmsen L, Faergeman O, et al. Follow-up study of patients randomized in the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study (4S) of cholesterol lowering. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00910-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sever PS, Poulter NR, Dahlof B, et al. The Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial lipid lowering arm: extended observations 2 years after trial closure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:499–508. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1556–1565. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridker PM, Wilson PW, Grundy SM. Should C-reactive protein be added to metabolic syndrome and to assessment of global cardiovascular risk? Circulation. 2004;109:2818–2825. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132467.45278.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smilde TJ, van Wissen S, Wollersheim H, et al. Effect of aggressive versus conventional lipid lowering on atherosclerosis progression in familial hypercholesterolaemia (ASAP): a prospective, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2001;357:577–581. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]