Abstract

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a cardinal and complex syndrome tightly linked to several co-morbidities, and is currently emerging as a new public health problem in the elderly population. However, despite aggressive intervention, patients with HFpEF typically have a poor prognosis. Part of the reason underlying this phenomenon can be attributed to the insufficiently understood pathophysiology behind this syndrome. Traditional echocardiography-derived parameters such as left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF) may not be useful in characterizing such a clinical disorder, or in further identifying the subjects at risk, owing in part to its lack of power to disclose subclinical systolic dysfunction in such a clinical scenario. Herein, we briefly reviewed the clinical manifestations and risk factors of HFpEF, and further provided insights into the understanding of the ventricular architecture and cardiac mechanics underlying HFpEF by utilizing advanced cardiovascular imaging modalities, with a special focus on myocardial deformation.

Keywords: Heart failure, Speckle tracking imaging, Strain

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome that correlates with many comorbidities and has caused a significant impact on human health and disabilities.1 Several clinical variables such as demographic information, laboratory tests, electrocardiographic and other imaging-based modalities had recently been shown to help stratify clinical outcomes in this patient population.2 A traditional marker of left ventricular (LV) contractile function such as LV ejection fraction (LVEF), when defined by the difference of between LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume indexed to LV end-diastolic volume, remained as the major index of LV systolic function and may also serve as a key prognosticator in systolic heart failure (HFrEF, defined by LVEF < 40% or < 50%).3 On the other hand, symptoms or signs of HF not completely distinguishable from subjects with HFrEF may also manifest in those with relatively preserved EF (HFpEF) as a possible distinct HF population, with a commonly set cut-off of LVEF exceeding 40% to 45%. The patients with HFpEF are more likely to be older, have larger body mass index, and are predominantly female, with a high prevalence of concomitant co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and atrial fibrillation.4,5 Recently, some authors have suggested that the prognosis may not differ significantly between these two HF groups (HFrEF or HFpEF) based on large community or admission cohorts,6,7 making HFpEF a substantial challenging public health issue, with an increasing burden on the elderly population. The overall prevalence of HFpEF was estimated to be 1.1-5.5% in the general population and actually comprised a relatively large proportion (40-71%, mean 54%) of all clinical HF patients.5

Among the patients with HFpEF, LVEF per se may not be adequate to evaluate the potential functional disturbances of LV. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop some other imaging methods or modalities both to identify and to explain the mechanisms underlying earlier stage myocardial mechanical failure in this patient population. Herein, we reviewed the advances and concepts in imaging parameters associated with cardiac geometry and deformation, and further described the observations and findings within the context of early cardiac mechanical failure and HFpEF.

ARCHITECTURE OF LV MYOCARDIUM AND THE DYNAMICS OF “TWIST/TORSION”

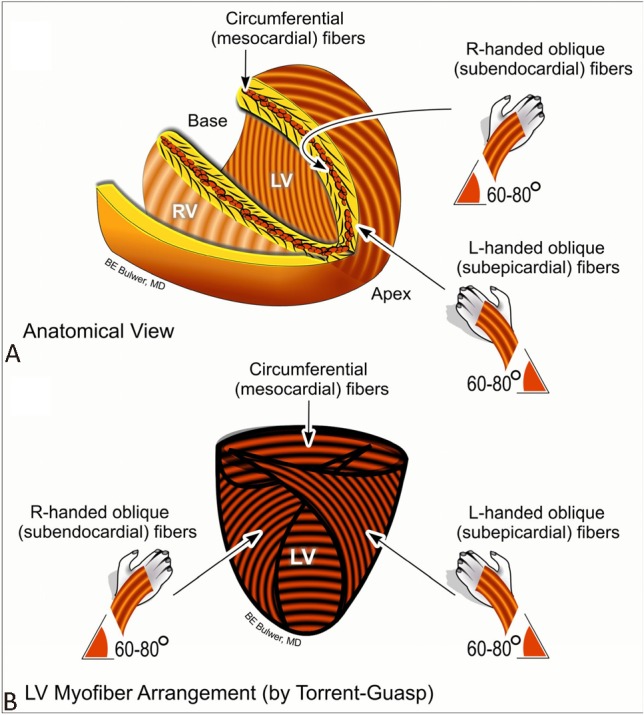

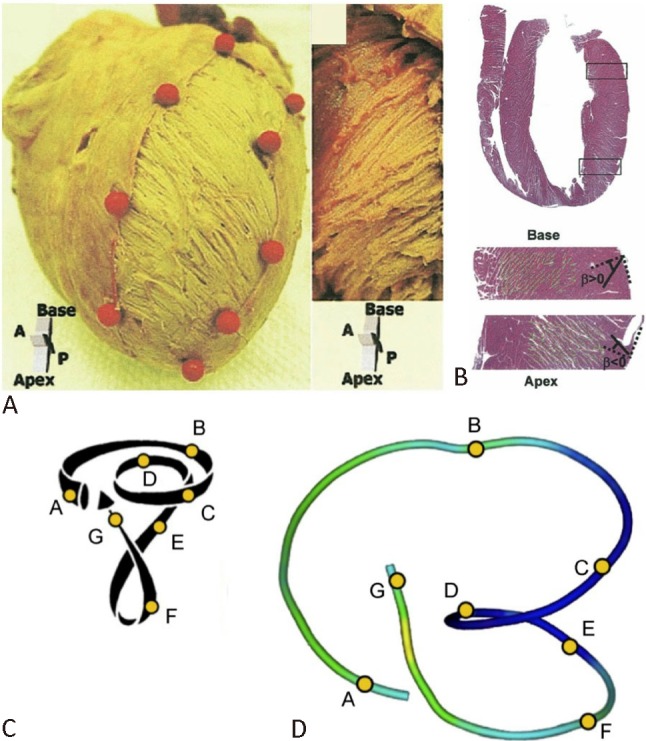

Essentially, LV is a hollow bullet-shape chamber which normally contracts and relaxes with reliable effectiveness. How this perfect mechanism works in a highly-efficient manner is actually based on the architecture of LV myocardium.8,9 In view of individual myofibers, subendocardial myofibers except papillary muscles run counterclockwise in the direction from the mitral annulus (LV base) towards the LV apex, and then convert to a circumferential direction forming the middle layer of myocardium. The 2 distinct helicoids muscle band theory proposed by Torrent-Guasp et al. highlighted the new conceptual framework of how opposite helical fibers aligned from the base-to-apex direction from a single muscle band can be folded, cross-bridged and functioning synergistically.10

Thereafter, they shift to run clockwise in the direction from the LV apex to the mitral annulus, forming the subepicardial myofiber layer. Because of these arrangements over the transmural myocardial continuum, subendocardial and subepicardial myofibers form two counter-directional helixes (right-hand helix in subendocardium and left-hand helix in subepicardium), making them aligned predominantly in longitudinal and oblique orientation. In the direction from the LV apex towards the LV base, subendocardium runs clockwise and subepicardium runs counterclockwise, creating an apex-to-base shear gradient. Conversely, the middle layer of myocardium is arranged in circumferential direction as described above. During the dynamics of both longitudinal and circumferential myofiber shortening, a substantial degree of myocardial sliding and transmural shearing happens,11 generating myocardial wall thickening in the radial direction,12 maximal cavity volume reduction and high fraction ejection. Furthermore, by using mathematical computational model, transmural wall stress and strain can be evenly distributed and optimized based on the counter-directional helical arrangement of myocardium against intra-cavity pressure with minimal energy consumption.13

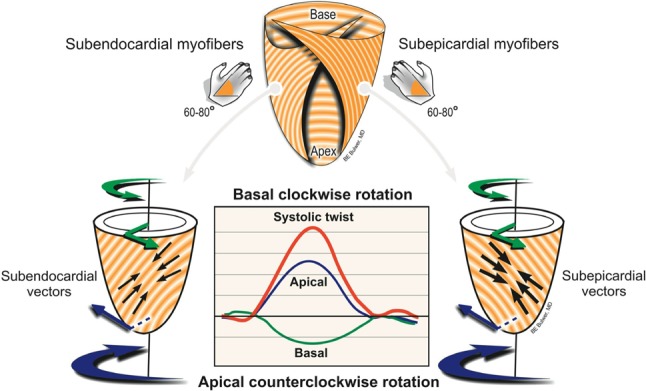

For each specific ventricular cross-sectional plane at any level, there is a “rotation” angle for a specific point at any time in the myolaminar sheet of varied directions (either clockwise or counter-clockwise during myocardial systole, and vice versa during diastole), in part driven by the opposite contractile direction of subendocardium and subepicardium longitudinal/oblique myofibers during the whole cardiac cycle.14 As a result, these fibers wrap up the whole LV in a complex and specific manner which may generate a highly efficient wringing motion with minimal energy expenditure during systolic contraction,9 generating a net “torsional” behavior with a relatively small degree of myocardial shortening in maintaining adequate cardiac output. While most literature has represented twist as rotational angle differences between apical and basal cross-sectional planes on the epicardial surface,15 the normalization of such parameter by LV length refers to the net LV twist angle or the net LV torsion angle (degrees per centimeter or radians).16 In addition, such complex myocardial torsional mechanics are not merely limited to ventricular systole/diastole, but can also happen within iso-volumic contraction, and have been proposed to be the warm-up phenomenon for subsequent efficient myocardial contraction/relaxation.17,18 The architecture of LV myocardium is summarized in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Schema showing the helical orientation of the left ventricular (LV) myofibers in anatomical position, as described by Torrent-Guasp (A). Schema showing the left-handed subepicardial myofibers oriented obliquely opposite, but in continuity with the right-handed subendocardial myofibers (B).

Figure 2.

Helical arrangement of myofibers in left ventricle. (A) Left-handed helix in the subepicardium and right-handed helix in the subendocardium in the left ventricle of an explanted porcine heart. (B) Longitudinal cross section of left ventricle fixed in diastole (hematoxylin and eosin stain) and radial orientation of the cleavage planes. (C) Torrent-Guasp helical ventricular myocardial band model. (D) Tractography reconstruction of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Reproduced from Sengupta PP et al.8 and Poveda F et al.9 with permission.

STRAIN AND SPECKLE TRACKING IMAGING IN ASSESSING CARDIAC MECHANICS

Myocardial deformation, a dimensionless index that can be simply expressed as strain, is defined as the percentage of length change between two points during a cardiac cycle, compared with the original length in end-diastole as the following equation:

Strain = 100 × (L - Lo)/Lo;

L: length at specific moment;

Lo: length in end-diastole.

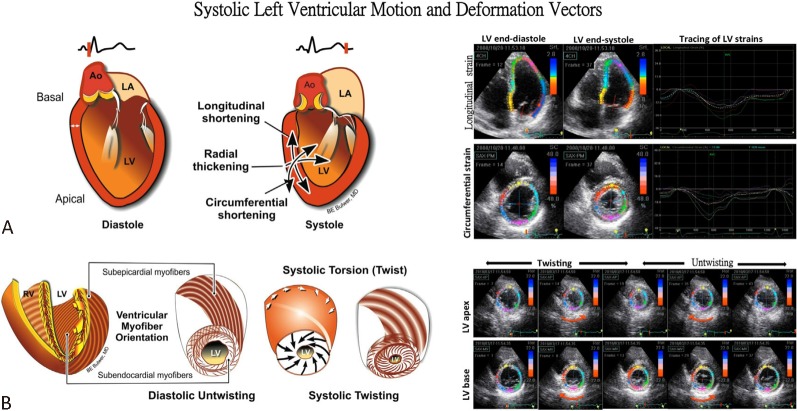

As mentioned above, biophysical LV deformation can be categorized into 3 different, perpendicular components19 with highly efficient synergistic coordination achieved based on the directions of myofiber sheets (longitudinal and circumferential) and the cross-fiber shortening effects leading to wall thickening (radial) (Figure 3A). Based on the definition, negative values of strain represent shortening of myocardium, with myocardial lengthening presenting positive values. Speckle tracking imaging as an emerging echocardiography technique allows B-mode speckle identification from two-dimensional images. Subsequently, it traces their motion frame-by-frame independent of echo-beam direction, so that regional or global events of 3 cardiac deformation components19 as well as torsional dynamic20 can be obtained and analyzed with high temporal resolution (Figure 3B and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Left ventricular (LV) motion and deformation during diastole and systole. Systole involves myocardial motion and deformation along three measurable vectors that result in LV shortening in the longitudinal axis, and thickening along both the radial and circumferential directions (A). Additionally, the complex myofiber arrangement facilitates LV systolic twisting and diastolic untwisting (recoil). This constitutes LV torsion or “wringing” (B). Speckle tracking images of these motions were demonstrated.

Figure 4.

Left ventricular (LV) torsion involves complex myofiber mechanics along multiple vectors. Note the simultaneous but obliquely opposite contractile vectors that result in LV torsion. LV systolic torsion or twisting involves a measurable gradient of rotation along the LV long-axis, with an apical counter-clockwise rotation and a basal clockwise rotation. Note the greater magnitude of the apical rotation compared to that of the base, and the relative magnitude of the systolic twist compared to the individual rotational vectors.

Speckle tracking technique as a major breakthrough in the long-standing history of echocardiography development could be an advantageous opportunity for us to look into the complex dynamics of cardiac motions independent of echo-beam direction. Since aging and hypertension remains as the theoretical major risk factors for HFpEF development,5 the association and possible effects of these variables on cardiac mechanics had gained much attention. Hypertension as a major risk for HF had been shown to cause adverse LV remodeling, worse longitudinal strain21 as an early, sensitive marker to hypertension, and hypertension-related subendocardial ischemia or fibrosis had been consistently proven.22 Instead, a relatively preserved circumferential function and augmented LV twist/torsion, which remained consistently preserved in the transition to HFpEF.23,24 Similar LV mechanics were also observed in those with well compensated LVH or aortic valve stenosis,25-28 indicating a possible compensatory role of LV twist/torsion to maintain adequate ejection performance in response to elevated afterload status. While LVH had been traditionally regarded as precursor of HFpEF, whether these short-axis functions may behave parallel with the same patterns in these two clinical scenarios remained controversial. Interestingly, aging and higher blood pressure, both key pathophysiologic factors proposed to be the major risks for HFpEF,29 had been shown to be associated with greater LV twist/torsion with female gender predominance in those subjects free from clinical symptoms.30 This finding may potentially suggest a compensatory role of LV twist/torsion in maintaining adequate cardiac output for those with higher clinical HF risks or unfavorable LV remodeling. Compared to HFpEF, subjects with HFrEF had a more severe degree of longitudinal functional decline, and further demonstrated uniformly deteriorated circumferential, radial deformation and twist/torsional mechanics31 (Table 1 and Table 2). These strains obtained by 2-dimenstional speckle tracking echocardiography were proven to be a new prognostic indicator in line with HFrEF.32,33 However, there is some controversy that these speckle tracking-based measures on twist or torsion may largely depend on tracking techniques, and whether subendocardial or epicardial tracking is efficacious.34 Moreover, the mechanism of three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography has developed recently and rather quickly. It has the advantage of reduced acquisition time and more parameters obtained (such as area tracking, time-to-peak systolic strain and site of latest mechanical activation).35

Table 1. General representation of LV systolic mechanics in the patients with heart failure.

| No HF | With risks of HF | HFpEF | HFrEF | |

| LVEF, % | Normal | Normal | Normal | Reduced |

| Longitudinal strain, % | Normal | Normal or reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Circumferential strain, % | Normal | Normal or reduced | Normal or reduced | Reduced |

| Twist, ° or Torsion, °/cm | Normal | Normal or augmented | Normal or reduced | Reduced |

HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Table 2. Recent studies of left ventricular deformation using speckle tracking echocardiography.

| Studygroups | Patientgroups | N | Age | Male, % | LVEF, % | E/e′ | Peak longitudinal strain, % | Peak circumferential strain, % | Peak radial strain, % | Twist, ° | Devices |

| Sengupta et al. 21 | HTN | 34 | 36 ± 3 | 56 | 67 ± 5 | NA | -13.4 ± 5.8‡ | -19 ± 9.6 | 17.2 ± 10.3 | NA | HD 7, Philips |

| Control | 25 | 33 ± 4 | 70 | 65 ± 5 | NA | -20.2 ± 4.7 | -23.5 ± 8.8 | 20.3 ± 11.3 | NA | ||

| Mizuguchi et al. 25 | HTN & C-LVH | 25 | 62 ± 10 | 64 | 70.4 ± 11.8† | 10.3 ± 4.1† | -17.9 ± 2.9‡ | -20.4 ± 4.5† | 62.7 ± 14.4† | 21 ± 6.8 | Vivid 7, GE |

| Control | 22 | 59 ± 12 | 32 | 77.4 ± 8.1 | 7.3 ± 2.4 | -22.9 ± 1.7 | -23.7 ± 3 | 74.4 ± 8 | 20.5 ± 6.5 | ||

| Delgadoet al. 26 | AS | 73 | 65 ± 13 | 56 | 61 ± 11 | NA | -14.6 ± 4.1‡ | -15.2 ± 5† | 33.1 ± 14.8 | NA | Vivid 7, GE |

| HTN & LVH | 20 | 66 ± 9 | 50 | 61 ± 7 | NA | -17.2 ± 3.7† | -17 ± 3 | 34.4 ± 10.7 | NA | ||

| Control | 20 | 65 ± 8 | 35 | 62 ± 7 | NA | -20.3 ± 2.3 | -19.5 ± 2.9 | 38.9 ± 6.4 | NA | ||

| Wanget al. 23 | Systolic HF | 30 | 52 ± 15* | 80* | 24 ± 9* | NA | -4 (-7, -3)* | -7 ± 3* | 14 ± 8* | 5 ± 2* | Vivid 7, GE |

| Diastolic HF | 20 | 63 ± 16* | 70* | 63 ± 6 | NA | -12 (-13, -8)* | -15 ± 5 | 28 ± 9 | 13 ± 6 | ||

| Control | 17 | 42 ± 11 | 29 | 64 ± 6 | NA | -19 ± 1.9 | -20 ± 3 | 47 ± 7 | 14 ± 5 | ||

| Yip et al. 31 | HFrEF | 175 | 67 ± 13‡ | 70* | 31.1 ± 8.6‡ | 21.4 ± 10.7‡ | -9.6 ± 3.6‡ | -9.5 ± 3.3‡ | 18 ± 9.7‡ | 8.2 ± 5.3‡ | Vivid 7, GE |

| HFpEF | 112 | 74 ± 12‡ | 36* | 61.2 ± 6.3‡ | 19.9 ± 9.7‡ | -15.9 ± 3.9‡ | -20.8 ± 4.9‡ | 32.9 ± 10.6‡ | 16.3 ± 7.1‡ | ||

| Control | 60 | 53 ± 10 | 52 | 67.6 ± 4.3 | 8.5 ± 2.2 | -20.9 ± 2.5 | -26.4 ± 3.5 | 44.5 ± 10.2 | 21.6 ± 5.2 |

* p < 0.05 versus control; † p < 0.01 versus control; ‡ p < 0.001 versus control.

C-LVH, concentric left ventricular hypertrophy; E/e′, the ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow to early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity; GE, general electric; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HfrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HTN, hypertension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; N/A, data not available.

LEFT ATRIAL MECHANICS AND HFpEF

The left atrial (LA) mechanics can actually be divided into three different phases during the whole cardiac cycle: (1) the reservoir phase, when the LA receives pulmonary venous return during LV systole (from mitral valve closure to opening) and stores potential energy; (2) the conduit phase, when the LA passively transfers blood to the LV during early diastole, the function of which is relatively dependent on LV relaxation and preload; and (3) the contractile phase, when the LA actively boosts LV in late diastole for subsequent ventricular systole. At this phase, the energy stored during the LA reservoir phase is released and converts to kinetics and further contributes to LV stroke volume.36

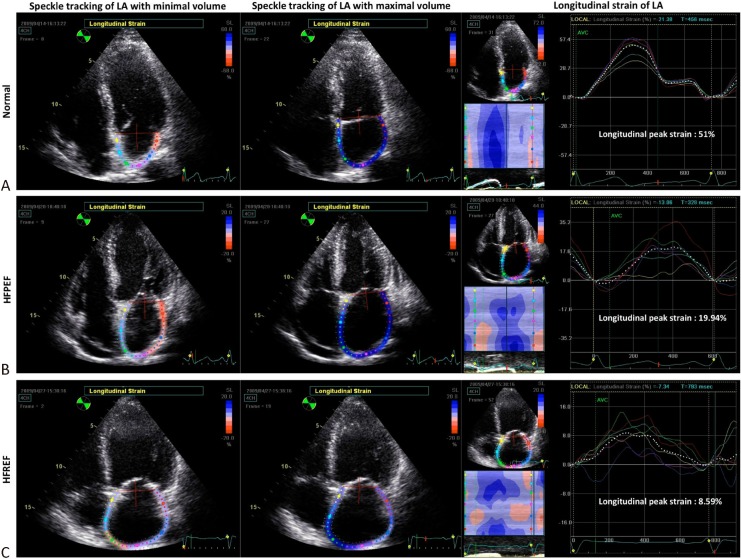

Recently, speckle tracking imaging has been used not only in evaluating LV deformation but also in left atrial (LA) mechanical indices.36-38 During the reservoir phase, LA strain gradually increases until reaching its peak at LV end-systole. LA strain rate pattern during reservoir phase typically shows two peaks. The early peak corresponds to iso-volumic contraction period and largely reflects LA compliance, whereas the late peak corresponds to LV ejection and iso-volumic relaxation period.36 Impairment of LA deformation indices is associated with LV diastolic dysfunction, either represented as Doppler velocities39 or end-diastolic pressures40 in heart failure patients. Because worse LA reservoir function can directly reflect elevated LV filling pressure, it is more sensitive to changes in LV diastolic function, so marked reductions in reservoir function might already occur during early-stage heart failure.39 On the other hand, LA contractile function may be augmented at this stage to compensate for reduced LA-to-LV filling process resulting from stiffening of the LV. In addition, early LA dysfunction had also reportedly has occurred in patients with hypertension and diabetes prior to volume changes.41 Therefore, impaired longitudinal LA peak strain may be another useful echo-derived index for patients with HFpEF in recent years39 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Demostration of left atrial (LA) strains by speckle tracking imaging in different phenotypes of heart failure. Examples of LA longitudinal strains in three subjects of (A) normal, (B) heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and (C)heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) were shown. The normal one had the highest global peak strain (51%) and the patient with HFrEF had the lowest global peak strain (8.59%). Global peak strain of whom with HFpEF (19.94%) had the values between them. The dotted white lines and colorized lines in the tracing represented global and regional strain respectively.

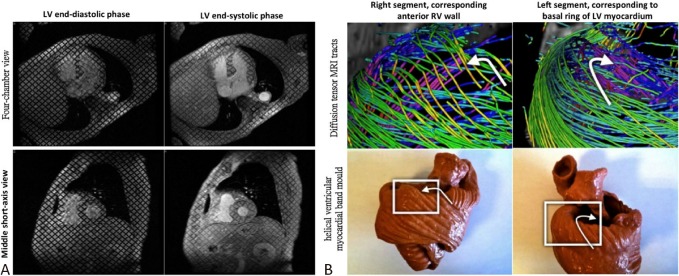

CARDIAC MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (CMR) AND COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY (CT) IN ASSESSING CARDIAC MECHANICS

With retrospective gating, cardiac CT not only provides critical information regarding coronary artery stenosis but also may help to evaluate cardiac function.42 Recently, hemodynamic assessment of transmitral flow velocity and mitral annulus tracking techniques by CT enables myocardial functional descriptions close to 2D echocardiography.43 So far, CMR remains the “gold standard” for assessing both left and right ventricular function, mass and volumes.44 Besides, owing to the 3D volume acquisition nature of these imaging modalities, both CMR and CT can provide more accurate LA volume measures, which had been shown to be an important predictor of adverse cardiovascular events, such as atrial fibrillation and heart failure.45 Beyond the functional evaluation, the technologies of 3D cine displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) utilizing CMR tagging (Figure 6) also provide information about myocardial biophysics46 and twist/torsion mechanics.47 Diffusion tensor MRI, another advanced skill, further characterizes information regarding myocardial architecture and spatial orientation of myofibers using several visual 3-dimensional levels of anatomical complexity.48 Finally, late gadolinium myocardial enhancement (LGE), has alternatively been used for identifying scar formation after myocardial infarction, various patterns of intra-myocardial fibrosis in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy,49 and impairment of diastolic dysfunction.50

Figure 6.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. (A) Tagging images in evaluating wall motion of the heart. (B) Comparison between diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging tracts and a helical ventricular myocardial band mould. Reproduced from Poveda F et al.9 with permission.

CONCLUSIONS

HFpEF remains as an important public health issue, and is currently an emerging and growing phenomenon. The major advances and evolution of several novel imaging modalities such as echo-derived speckle tracking imaging, CMR and CT may provide insights into understanding the underlying cardiac mechanics in this patient population. Impaired myocardial deformation may occur even prior to overt onset of systolic dysfunction, when defined by reduced conventional LVEF. Moreover, the applications of such imaging modalities have been increasingly used in daily clinical routine to identify subjects at risk of HF and for clinical outcome prediction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohn JN, Johnson GR, Shabetai R, et al. Ejection fraction,peak exercise oxygen consumption, cardiothoracic ratio, ventricular arrhythmias, and plasma norepinephrine as determinants of prognosis in heart failure. The V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group. Circulation. 1993;87:VI5–VI6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J . 2012;33:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults:a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines:developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–e479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DS, Gona P, Vasan RS, et al. Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction:insights from the Framingham heart study of the national heart, lung, and blood institute. Circulation. 2009;119:3070–3077. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:18–28. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sengupta PP, Korinek J, Belohlavek M, et al. Left ventricular structure and function: basic science for cardiac imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1988–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poveda F, Gil D, Marti E, et al. Helical structure of the cardiac ventricular anatomy assessed by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging with multiresolution tractography. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torrent-Guasp F, Ballester M, Buckberg GD, et al. Spatial orientation of the ventricular muscle band: physiologic contribution and surgical implications. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:389–392. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa KD, Takayama Y, McCulloch AD, Covell JW. Laminar fiber architecture and three-dimensional systolic mechanics in canine ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H595–H607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rademakers FE, Rogers WJ, Guier WH, et al. Relation of regional cross-fiber shortening to wall thickening in the intact heart. Three-dimensional strain analysis by NMR tagging. Circulation. 1994;89:1174–1182. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vendelin M, Bovendeerd PH, Engelbrecht J, Arts T. Optimizing ventricular fibers:uniform strain or stress,but not ATP consumption,leads to high efficiency. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1072–H1081. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00874.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz CH, Pastorek JS, Bundy JM. Delineation of normal human left ventricular twist throughout systole by tagged cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2000;2:97–108. doi: 10.3109/10976640009148678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delhaas T, Kotte J, van der Toorn A, et al. Increase in left ventricular torsion-to-shortening ratio in children with valvular aortic stenosis. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:135–139. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henson RE, Song SK, Pastorek JS, et al. Left ventricular torsion is equal in mice and humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1117–H1123. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashikaga H, van der Spoel TI, Coppola BA, Omens JH. Transmural myocardial mechanics during isovolumic contraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashikaga H, Criscione JC, Omens JH, et al. Transmural left ventricular mechanics underlying torsional recoil during relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H640–H647. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00575.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurlburt HM, Aurigemma GP, Hill JC, et al. Direct ultrasound measurement of longitudinal, circumferential, and radial strain using 2-dimensional strain imaging in normal adults. Echocardiography. 2007;24:723–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helle-Valle T, Crosby J, Edvardsen T, et al. New noninvasive method for assessment of left ventricular rotation: speckle tracking echocardiography. Circulation. 2005;112:3149–3156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sengupta SP, Caracciolo G, Thompson C, et al. Early impairment of left ventricular function in patients with systemic hypertension:new insights with 2-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Algranati D, Kassab GS, Lanir Y. Why is the subendocardium more vulnerable to ischemia? A new paradigm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1090–H1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00473.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Khoury DS, Yue Y, et al. Preserved left ventricular twist and circumferential deformation, but depressed longitudinal and radial deformation in patients with diastolic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1283–1289. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed MI, Desai RV, Gaddam KK, et al. Relation of torsion and myocardial strains to LV ejection fraction in hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizuguchi Y, Oishi Y, Miyoshi H, et al. Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy brings deterioration of systolic longitudinal, circumferential, and radial myocardial deformation in hypertensive patients with preserved left ventricular pump function. J Cardiol. 2010;55:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delgado V, Tops LF, van Bommel RJ, et al. Strain analysis in patients with severe aortic stenosis and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction undergoing surgical valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:3037–3047. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini FM, et al. Left ventricular remodeling and torsion dynamics in hypertensive patients. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popescu BA, Calin A, Beladan CC, et al. Left ventricular torsional dynamics in aortic stenosis: relationship between left ventricular untwisting and filling pressures. A two-dimensional speckle tracking sudy. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:406–413. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung CL, Wu YJ, Liu CC, et al. Age-related ventricular remodeling is an independent risk for heart failure symptoms in subjects with preserved systolic function. Int J Gerontol. 2011;5:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoneyama K, Gjesdal O, Choi EY, et al. Age, sex, and hypertension-related remodeling influences left ventricular torsion assessed by tagged cardiac magnetic resonance in asymptomatic individuals: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;126:2481–2490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.093146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yip GW, Zhang Q, Xie JM, et al. Resting global and regional left ventricular contractility in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction:insights from speckle-tracking echocardiography. Heart. 2011;97:287–294. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.205815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mignot A, Donal E, Zaroui A, et al. Global longitudinal strain as a major predictor of cardiac events in patients with depressed left ventricular function: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho GY, Marwick TH, Kim HS, et al. Global 2-dimensional strain as a new prognosticator in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goffinet C, Chenot F, Robert A, et al. Assessment of subendocardial vs. subepicardial left ventricular rotation and twist using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: comparison with tagged cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:608–617. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ammar KA, Paterick TE, Khandheria BK, et al. Myocardial mechanics: understanding and applying three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in clinical practice. Echocardiography. 2012;29:861–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2012.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Todaro MC, Choudhuri I, Belohlavek MJ, et al. New echocardiographic techniques for evaluation of left atrial mechanics. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:973–984. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DG, Lee KJ, Lee S, et al. Feasibility of two-dimensional global longitudinal strain and strain rate imaging for the assessment of left atrial function: a study in subjects with a low probability of cardiovascular disease and normal exercise capacity. Echocardiography. 2009;26:1179–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameli M, Caputo M, Mondillo S, et al. Feasibility and reference values of left atrial longitudinal strain imaging by two-dimensional speckle tracking. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris DA, Gailani M, Vaz Perez A, et al. Left atrial systolic and diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakami K, Ohte N, Asada K, et al. Correlation between left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and peak left atrial wall strain during left ventricular systole. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:847–851. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mondillo S, Cameli M, Caputo ML, et al. Early detection of left atrial strain abnormalities by speckle-tracking in hypertensive and diabetic patients with normal left atrial size. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:898–908. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ko SM, Kim YJ, Park JH, Choi NM. Assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and regional wall motion with 64-slice multidetector CT: a comparison with two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:28–34. doi: 10.1259/bjr/38829806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boogers MJ, van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, et al. Feasibility of diastolic function assessment with cardiac CT: feasibility study in comparison with tissue Doppler imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong AC, Gidding S, Gjesdal O, et al. LV mass assessed by echocardiography and CMR, cardiovascular outcomes, and medical practice. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balli O, Aytemir K, Karcaaltincaba M. Multidetector CT of left atrium. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e37–e46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shehata ML, Cheng S, Osman NF, et al. Myocardial tissue tagging with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:55. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gotte MJ, Germans T, Russel IK, et al. Myocardial strain and torsion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance tissue tagging: studies in normal and impaired left ventricular function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2002–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poveda F, Gil D, Martí E, et al. Helical structure of the cardiac ventricular anatomy assessed by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging with multiresolution tractography. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Judd RM, et al. Delayed enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1461–1474. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moreo A, Ambrosio G, De Chiara B, et al. Influence of myocardial fibrosis on left ventricular diastolic function: noninvasive assessment by cardiac magnetic resonance and echo. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:437–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.838367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]