Abstract

Studies examining economic hardship consistently have linked family economic hardship to adolescent adjustment via parent and family functioning, but limited attention has been given to adolescents’ perceptions of these processes. To address this, the authors investigated the intervening effects of adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and of parent-adolescent warmth and conflict on the associations between parental economic hardship and adolescent adjustment (i.e., depressive symptoms, risky behaviors, and school performance) in a sample of 246 Mexican-origin families. Findings revealed that both mothers’ and fathers’ reports of economic hardship were positively related to adolescents’ reports of economic hardship, which in turn, were negatively related to parent-adolescent warmth and positively related to parent-adolescent conflict with both mothers and fathers. Adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship were indirectly related to a) depressive symptoms through warmth with mothers and conflict with mothers and fathers, b) involvement in risky behaviors through conflict with mothers and fathers, and c) GPA through conflict with fathers. Our findings highlight the importance of adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship and relationships with mothers and fathers in predicting adolescent adjustment.

Keywords: adolescent adjustment, economic hardship, Mexican American families, parent-adolescent relationship

Family economic hardship, or a psychological sense that the family is experiencing significant financial difficulties that produce distress within the family context (Barrera, Caples, & Tein, 2001), is associated with a variety of indicators of adolescent adjustment via proximal family processes (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). According to the family stress model, economic hardship predicts individual and relationship instability and, in turn, adolescent adjustment problems (Conger & Conger, 2002). A basic tenet of the family stress model is that economic pressures brought on by poor economic conditions (i.e., low income and job loss) are associated with individual (i.e., parent) adjustment problems and problematic family relationships (Donnellan, Conger, McAdams, & Neppl, 2009). In turn, problem relationships spill over to disrupt the social, emotional, cognitive, and physical development of children (Conger & Conger, 2002). This model of economic hardship’s impact on family and child functioning was originally tested with European American families, but has been extended to samples of families from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds in the last decade (Conger et al., 2002; Gonzales et al., 2011). Collectively, these findings suggest that, in a broad range of ethnic and racial contexts, parent functioning and family relationship processes mediate, or explain the relation of, family economic hardship-adolescent adjustment linkages.

Advances in social and cognitive development that characterize the period of adolescence (Keating, 2004; Smetana, 2011) suggest that adolescents may be more aware of their families’ circumstances than in earlier developmental periods, having implications for the impact of family hardship on their adjustment. To date, we know little about adolescents’ perceptions of their families’ economic circumstances and the role of these perceptions in parent-adolescent relationship dynamics and adolescent adjustment (Mistry, Benner, Tan, & Kim, 2009). A limited number of studies have tested the direct associations of adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship in European American (Conger et al., 1999) and African American families (McLoyd, Jayaratne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994). And, to our knowledge, one study has tested its prospective intervening effects, in a sample of Chinese families (Mistry et al., 2009), but no studies have examined adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship in a sample of Latino or, more specifically, Mexican-origin families. Furthermore, this is the first study to examine adolescents’ and both mothers and fathers’ perceptions of family economic hardship.

The present study drew from a family stress process model (e.g., Conger & Conger, 2002) and cognitive developmental perspective (e.g., Keating, 2004) to address two goals using a prospective design: (a) to investigate the intervening role of Mexican-origin adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship between parents’ reports of economic hardship and adolescents’ perceptions of parent-adolescent relationship qualities (i.e., warmth and conflict); and (b) to examine the intervening effects of parent-adolescent relationship qualities in the association between adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and their adjustment as indexed by depressive symptoms, risky behaviors, and school performance. Furthermore, because of gendered socialization practices in Latino families (Azmitia & Brown, 2002), we examined adolescent gender as a moderator of the links between adolescents’ reports of economic hardship and parent-adolescent relationship qualities and between parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment. We focus on Mexican-origin adolescents, a large and rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population who are, on average, at increased risk for poverty and economic hardship (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010a) and poor developmental outcomes (e.g., Wilkinson, Shete, Spitz, & Swann, 2011).

Economic Hardship, Parent-Adolescent Relationship Quality, and Adolescent Adjustment

Adolescence is a period characterized by substantial changes in adjustment, including increases in internalizing symptoms and externalizing behaviors and declines in school performance (Eccles, Lord, & Roeser, 1996). In the U.S., Mexican-origin adolescents are at risk for experiencing depressive symptoms (CDC, 2006), engaging in risky behaviors (e.g., Wilkinson et al., 2011), and performing poorly in school (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010b). Examining how economic hardship is linked to these three aspects of adjustment is important in order to provide insights into the ways economic hardship may be placing Mexican-origin adolescents at risk for different types of adjustment problems and to offer a more complete picture of the interrelations among hardship, parental warmth and conflict, and adjustment.

Scholars argue that to more fully understand the effects of stressful events on children and adolescents, their awareness or perceived understanding of the stressful events must be considered (Bloom-Feshbach, Bloom-Feshbach & Heller, 1982; Compas, 1987; Rutter, 1983). Taking into account children’s perceptions or subjective interpretations of family circumstances may be especially crucial in adolescence when individuals begin to take a more active role in their development (Scarr & McCartney, 1983) and make gains in cognitive abilities, such as being able to think in more complex ways and understand different perspectives (Keating, 2004). Importantly, adolescence also is a time when girls and boys begin to assess their own economic futures (e.g., making career choices), and thus, may pay closer attention to their families’ economic circumstances. Together, these progressions suggest that adolescents’ perceptions of their families’ economic hardship may be a critical component of processes linking family hardship to adolescent adjustment. Together, these progressions suggest that adolescents’ perceptions of their families’ economic hardship may be a critical component of processes linking family hardship to adolescent adjustment.

Research on the implications of marital discord for family dynamics and individual adjustment provides support for the important role of adolescents’ perceptions of family stressors (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Harold & Conger, 1997). The work of Harold and Conger (1997), for example, showed that adolescents’ awareness of marital conflict explained the relation between parent and observer ratings of marital conflict and adolescent ratings of parent hostility, and further, that adolescents’ perceptions of parent hostility explained the relation between awareness of marital conflict and adolescent adjustment. Turning to research on family economic hardship, there is evidence that adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship are positively associated with African American mothers’ perceptions of hardship (McLoyd et al., 1994), and with European American and Chinese American parents’ perceptions (i.e., the summed score of mother and father ratings; Conger et al., 1999; Mistry et al., 2009). In these same studies, adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain/hardship were linked to their psychosocial adjustment (e.g. depressive symptoms, anxiety). In the only study that examined the intervening role of adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship, Mistry et al. (2009) found that parent ratings of economic hardship were related to adolescents’ depressive symptoms through Chinese adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship. Together, these findings demonstrate the significance of adolescents’ perceived understanding of their families’ circumstances.

A central feature of the family stress model is the mediating role of family relationships (e.g., marital, parent-child) in the impact of stressful family circumstances on adolescent adjustment (e.g., Conger & Conger, 2002). Indeed, a body of research reveals that stressful family circumstances are associated with lower levels of parent-adolescent warmth (e.g., Schofield et al., 2011), including in Mexican American families (Gonzales et al., 2011). Further, in a study on stress and coping, higher levels of parent-adolescent conflict were predicted by adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain (e.g., Wadsworth & Compas, 2002). This work is consistent with models positing that childhood stress leads individuals to perceive more conflict and less warmth from others (see Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011).

In families of Mexican-origin, the cultural emphasis on family (Hardway & Fuligni, 2006; García-Coll & Vázquez García, 1995) also highlights the parent-adolescent relationship as an important proximal process predicting adjustment in the face of family economic hardship. Adolescents in families of Mexican descent, for instance, are expected to identify with a familistic orientation, in which the family is valued as a primary source of support (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). Thus, considering how stressors directly relate to adolescents’ cognitions of their key relationships in this highly cohesive context is an important next step. Research drawing from a family stress model provides evidence that parenting behaviors mediate the relation between economic hardship and adolescent adjustment (e.g., Grant et al., 2003). Synonymously, from the adolescents’ perspective, adolescents’ views of their relationships with their parents may also explain how family hardship relates to adjustment.

The Role of Mothers and Fathers in Mexican-origin Families

Demographic trends highlight the presence of both mothers and fathers in Mexican-origin adolescents’ daily lives in the U.S., as 69% of Mexican-origin households with children under the age of 18 in the U.S. include two-parent married families (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Scholarship on parenting further points to the potentially different roles of mothers and fathers in family life (Parke & Buriel, 2006). Qualitative research with Mexican American adolescents, for example, suggests that adolescents described more open communication with mothers relative to fathers (Crockett, Brown, Russell, & Shen, 2007). Thus, warmth and acceptance from mothers may be a more salient intervening factor in economic hardship-adjustment linkages than from fathers. Given research on parent-adolescent conflict reveals consistent links to adolescent adjustment difficulties in Mexican-origin and Latino families (e.g., Pasch et al., 2006), perceptions of both mother- and father-adolescent conflict are likely linked to adolescent adjustment.

Moderating Role of Adolescent Gender

Research suggests girls and boys respond differently to economic stressors (Coltrane et al., 2008; Elder & Caspi, 1998; McLoyd, 1989), and in particular, that boys respond more negatively to stressors than girls (e.g., Coltrane et al., 2008). In Mexican-origin families, an emphasis on traditional caretaking roles for girls and freedom and autonomy outside the home for boys, may mean that boys are expected to contribute to the family’s financial well-being through outside employment, and thus, boys may be more cognizant of family financial stressors than girls. In addition, a gender intensification perspective (e.g., Hill & Lynch, 1983) emphasizes the socialization role of the same-sex parent in early to middle adolescence. Thus, it is possible that mother-adolescent relationship qualities will be more strongly linked to girls’ as compared to boys’ adjustment and father-adolescent relationship qualities will be more strongly linked to boys’ than to girls’ adjustment.

Present Study

In the present study, we extend previous work in three important ways. First, we move beyond parents’ perceptions of family hardship to include adolescents’ perceptions of both their families’ economic hardship and parent-adolescent relationship qualities, as important psychological and intervening factors between parents’ perceptions of economic hardship and adolescents’ adjustment. Second, we test adolescents’ perceptions of their relationships with both mothers and fathers, as fathers have been relatively neglected in research on Latino families (Parke & Buriel, 2006). Third, we examine how parent-adolescent warmth and conflict are linked to three indicators of adolescent adjustment to provide a more comprehensive picture of how economic hardship is linked to different dimensions of the parent-adolescent relationship and, in turn, different aspects of adjustment (i.e., depressive symptoms, risky behaviors, and performance in school). We argue that the suggested spillover that occurs from family disruptions to adolescent well-being in the context of family stress occurs via adolescents’ own conceptualizations of those disruptions.

Guided by a family stress process model and a cognitive developmental perspective, we hypothesized that family economic hardship, as perceived by mothers and fathers, would be positively related to adolescents’ perceptions of family hardship; in turn, adolescents’ perceptions of hardship would be associated with lower levels of parental warmth and higher levels of conflict (e.g., Gonzales et al., 2011). We further expected that warmth would predict positive outcomes (i.e., fewer depressive symptoms and risky behaviors and higher grades in school), whereas conflict would predict more adjustment difficulties (i.e., more depressive symptoms and risky behaviors and lower grades in school). In addition, we explored adolescent gender as a moderator of the economic hardship-parent-adolescent relationship quality link and of the parent-adolescent relationship quality-adjustment link. Given prior evidence of direct linkages between economic hardship and adolescent adjustment (McLoyd et al., 1994; Mistry et al., 2009) and between parent-adolescent relationship quality and adolescent adjustment (Lau, et al., 2005; Pasch et al., 2006), these direct paths were included in our models. Family income was included as a covariate to test how perceived economic hardship, after taking into account family income level, was associated with family relationships and adolescent adjustment.

Method

Participants

The data came from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican-origin families (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005). The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around a southwest metropolitan area. Criteria for participation were as follows: (1) mothers were of Mexican origin; (2) a 7th grader was living in the home and not learning disabled; (3) an older sibling was living in the home (in all but two cases, the older sibling was the next oldest child in the family); (4) biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers (i.e., minimum of 10 years) lived at home; and (5) fathers worked at least 20 hours/week. Most fathers (i.e., 93%) also were of Mexican origin.

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in both English and Spanish) were sent to families, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Families’ names were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools. Schools were selected to represent a range of socioeconomic situations, with the proportion of students receiving free/reduced lunch varying from 8% to 82% across schools. Letters were sent to 1,856 families with a Hispanic 7th grader who was not learning disabled, but contact information was correct for 1,460 families. Thus, 396 families never received the recruitment letter or a follow-up phone call. Of the 1,460 families for whom we had correct contact information, 421 families were identified as eligible to participate (32% of the 1,460 families). Of these 421 families, 284 agreed to participate (67% of the 421 families) and 246 completed interviews (58% of the 421 eligible families). See Updegraff, McHale, & Crouter (2006) for additional details about the sampling process and sampling representativeness.

Two years after the initial interview, we conducted follow-up interviews with target adolescents (n = 222 of the original 246 target adolescents; 90%). Twenty-four of the target adolescents did not participate in the interviews for one of the following reasons: they refused to participate (n = 9), their parent refused to give them permission to participate (n = 5), or we were unable to locate them (n = 10). The 222 adolescents who completed the interview at Time 2 did not differ significantly from the original 246 adolescents on family income, mothers’ education, fathers’ education, or number of children in the home. The present study uses data from mothers, fathers, and adolescents at Time 1 and from adolescents at Time 2 (as parent data were not collected at Time 2).

The 246 families represented a range of education and income levels, from poverty to upper class. At Time 1, the median family income was $40,000 (for two parents and an average of 3.39 children) and ranged from less than $3000 to over $250,000 (SD = $45,382). Mothers and fathers had completed an average of 10 years of education (Mmothers = 10.43, SD = 3.80 and Mfathers = 9.95, SD = 4.43). Sixty-seven percent of mothers and 68% of fathers completed the interview in Spanish. Most parents were born outside the U.S. (71% of mothers and fathers). For parents born in Mexico, mothers and fathers had lived in the U.S. an average of 12.36 (SD = 8.89) and 14.97 (SD = 8.50) years, respectively. Thirty-nine percent of target adolescents were born in Mexico and the remainder in the U.S. At Time 1, target adolescents (52% female) were 12.51 (SD = .58) years of age on average and 83% were interviewed in English.

Procedures

At Time 1, data were collected from parents and adolescents during in-home interviews. After completing informed consent (parents; parents for adolescents) and assent (adolescents), individual interviews were conducted using laptop computers in each family member’s preferred language and questions were read aloud by bilingual interviewers. Two years later (Time 2), adolescents were re-interviewed over the phone using the same procedures as Time 1. First, consent from parents and assent from adolescents were verbally recorded and then interviewers read questions to adolescents and entered their responses into the computer. In the present study, Time 1 measures included parents’ reports of family income and economic hardship, and adolescents’ reports of adjustment and Time 2 measures included adolescents’ reports of economic hardship, parent-adolescent relationship qualities, and adjustment.

Measures

All measures were forward- and back-translated for local Mexican dialect according to a procedure developed by Foster and Martinez (1995).

Family Income (Time 1)

Family income was assessed using parents’ reports of their annual income. A log transformation was applied to correct for positive skewness.

Parents’ Ratings of Economic Hardship (Time 1)

Mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of economic hardship were assessed using a measure developed by Barrera and colleagues (2001). This measure includes four subscales: (1) inability to make ends meet (2 items; e.g., “Think back over the past 3 months and tell us how much difficulty you had paying your bills”); (2) not having enough money for necessities (4 items; e.g., “My family had enough money to afford the kind of clothing we should have”); (3) economic adjustments or cutbacks (9 items; e.g., “In the last 3 months, has your family asked relatives or friends for money or food to help you get by because of financial need?”); and (4) financial strain (2 items; e.g., “In the next 3 months, how often do you expect that you will have to do without the basic things that your family needs?”). The composite score for each parent was created by taking the z-scores for each of the 4 scale scores, weighting those z-scores with each scale’s respective gamma weight, and then summing the weighted z-scores. Confirmatory factor analyses showed that the economic hardship latent factor was a good fit to the data (Barrera et al., 2001).

Adolescents’ Perceptions of Family Economic hardship (Time 2)

Adolescents reported on the degree of economic hardship that they perceived their family to experience during the past 3 months with the 5-item measure developed by Conger and colleagues (1999) using a 5-point scale (1 = no problem at all to 5 = a very serious problem). An example item is “How much of a problem does your family have because your parents do not have enough money to buy things your family needs or wants?” Items were averaged and higher scores indicated greater perceptions of economic hardship. Cronbach’s alpha was .82.

Parent-adolescent warmth (Time 2)

Adolescents rated warmth with their mothers and fathers during the past year using an 8-item subscale of the Children’s Reports of the Parent Behavior Inventory measure (Schwarz, Barton-Henry, & Pruzinsky, 1985), which has been validated in prior work with Mexican Americans (Knight, Virdin, & Roosa, 1994). Adolescents rated warmth from each parent on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always) at separate points in the interview (e.g., “My mother/father speaks to me in a warm and friendly voice.”). Items were averaged and higher scores indicated greater warmth. Cronbach’s alphas were .90 for warmth with mothers and .91 for warmth with fathers.

Parent-adolescent conflict (Time 2)

Parent-adolescent conflict was assessed using a 12-item measure adapted from Smetana (1988). Adolescents reported on the frequency of conflict in 12 domains (e.g., chores, homework, bedtime/curfew) during the past year, separately for mothers and fathers at different points in the interview, using a 6-point scale (1 = not at all to 6 = several times a day). Items were averaged and higher scores indicated a greater frequency of conflict. Cronbach’s alphas were .85 and .86 for conflict with mothers and fathers, respectively.

Adolescent Adjustment (Times 1 and 2)

Adolescents reported on three indices of adjustment: depressive symptoms, involvement in risky behaviors, and grade point average. They described their depressive symptoms in the last month with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression measure (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) using a scale from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most of the time). An example item is “During the past month, I felt that everything I did was an effort.” Item scores were summed and higher scores indicated greater depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alphas were .85 and .83 at Times 1 and 2, respectively. Involvement in risky behaviors was measured by the Risky Behavior Scale (Eccles & Barber, 1990). Adolescents reported on the frequency that they engaged in 23 problem behaviors, such as cheating on school tests and drinking alcohol without parents’ permission during the past year. Items were rated using a 4-point scale (1 = never to 4 = more than 10 times). Items were averaged and higher scores indicated greater involvement in risky behaviors. Cronbach’s alphas at Times 1 and 2 were .88 and .89, respectively. Finally, adolescents reported on their current grades in four core academic areas (i.e., English, Social Studies, Math, and Science) and their GPAs (i.e., grade point averages) were computed.

Analytic Plan

Our goals were to examine the indirect effects of a) parents’ reports of economic hardship and adolescents’ perceptions of parent-adolescent relationship qualities through adolescents’ perceptions of hardship; and b) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and adolescent adjustment through adolescents’ perceptions of parent-adolescent relationship qualities. Path analysis, a form of structural equation modeling with observed variables (Kline, 1998), was used to test the associations among parents’ ratings of economic hardship, adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship, parent-adolescent relationship qualities, and adolescent adjustment. Specifically, we examined the paths from parents’ ratings of economic hardship at Time 1 to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship at Time 2 to parent-adolescent relationship quality (i.e., warmth or conflict) at Time 2 to adolescent adjustment at Time 2 (depressive symptoms, involvement in risky behaviors, and GPA), controlling for Time 1 adjustment, family income, and gender. Additionally, direct paths between parents’ reports of economic hardship and adolescent adjustment and between adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and adolescent adjustment were included based on prior work (e.g., McLoyd et al., 1994; Mistry et al., 2009). Models were conducted separately for adolescents’ relationships with mothers and fathers. Covariances between (a) warmth and conflict, (b) family income and parents’ reports of economic hardship, (c) family income and Time 1 adjustment indices, (d) parents’ reports of economic hardship and Time 1 adjustment indices, and (e) adolescent adjustment indices at Time 2 were estimated. Finally, we examined adolescent gender as a moderator of the link between (a) adolescents’ reports of economic hardship and parent-adolescent relationship qualities and (b) parent-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment. Exogenous and intervening variables were centered and interaction terms were created for the models.

Results

Path analyses were conducted in MPlus Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010). Acceptable model fit was determined by a chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio below 3 (Kline, 1998), values above .90 on the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and values below .08 for the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Kline, 1998). Modifications consistent with theory and empirical research were made (Kline, 1998). To determine the significance of the indirect effects, we used the bias-corrected bootstrap method (MacKinnon, 2008), which estimates bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effects. The indirect effects are significant when the confidence intervals do not contain zero. Additionally, according to MacKinnon’s (2008) criteria for indirect effects, analyses were conducted even when the direct path from the independent variable to the outcome variable was not significant because the two variables may be related indirectly via a third variable. Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. The means for parents’ reports of individual items for economic hardship suggest that parents in our sample described moderate to high levels of economic hardship. On average, adolescents reported relatively low scores on economic hardship and involvement in risky behaviors, moderate levels of parent-adolescent conflict, relatively high scores on parental warmth and depressive symptoms, and GPAs that fell in the B− to C+ range.

Table 1. Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables (N = 222).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother economic hardshipa | --- | |||||||||||

| 2. Father economic hardshipb | .62** | --- | ||||||||||

| 3. Adol. economic hardship | .24** | .25** | --- | |||||||||

| 4. Family incomec | -.53** | -.56** | -.12 | --- | ||||||||

| 5. Adolescent gender | .10 | .05 | −.02 | −.10 | --- | |||||||

| 6. Warmth with mothers | −.00 | .07 | −.19* | −.13* | .03 | --- | ||||||

| 7. Warmth with fathers | −.07 | −.05 | −.25** | −.01 | .03 | .38** | --- | |||||

| 8. Conflict with mothers | .14* | .05 | .40** | −.01 | .09 | −.36** | −.14* | --- | ||||

| 9. Conflict with fathers | .14* | .07 | .37** | −.09 | .06 | −.20** | −.16* | .72** | --- | |||

| 10. Depressive symptoms | .19** | .15* | .15** | −.05 | −.28** | −.31** | −.22** | .35** | .33** | --- | ||

| 11. Risky behaviors | .13 | .04 | .26** | .09 | .16* | −.32** | −.26** | .50** | .33** | .23** | --- | |

| 12. GPA | −.27** | −.15* | −.15 | .19* | −.14 | .14* | .07 | −.29** | −.32** | −.15* | .38** | --- |

| M | −.03 | −.05 | 1.84 | 4.63 | 1.48 | 3.92 | 3.58 | 2.38 | 2.39 | 16.54 | 1.44 | 2.60 |

| SD | 2.56 | 2.48 | .69 | .30 | .50 | .98 | .87 | .92 | .79 | 8.38 | .33 | .83 |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01.

min value = −3.98, max value = 6.71.

min value = −3.80, max value = 8.50.

log transformation.

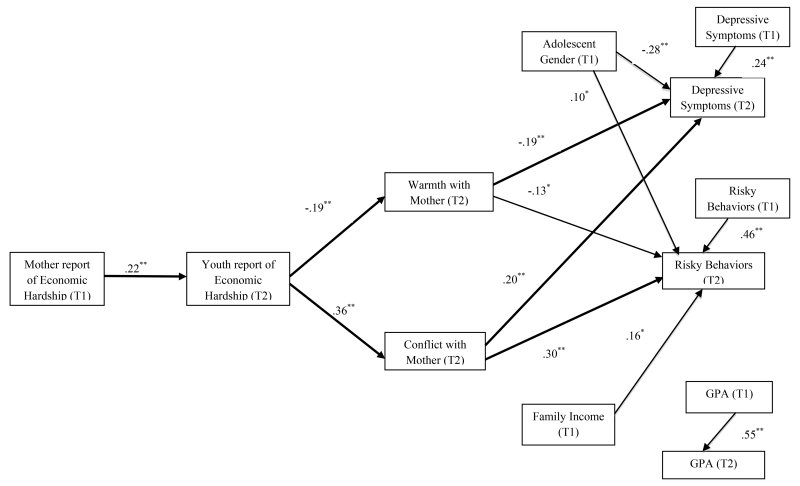

Model for Mothers

The model for mothers was an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (21) = 40.32, p < .01, χ2/df = 1.92, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06 (see Table 2; Figure 1). Mothers’ perceptions of economic hardship at Time 1 were positively associated with adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship at Time 2; adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship were negatively related to warmth and positively related to conflict with mothers at Time 2; warmth with mothers negatively predicted depressive symptoms and risky behaviors at Time 2, after controlling for Time 1, but not GPA; and conflict with mothers positively predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms and involvement in risky behaviors (at Time 2, controlling for Time 1), but not GPA. All Time 1 adjustment indices significantly predicted Time 2 adjustment. The direct paths between mothers’ and adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and adjustment were not significant. Finally, girls reported greater depressive symptoms and boys reported greater involvement in risky behaviors.

Table 2. Path Coefficients for Final Models.

| Model for Mothers | Model for Fathers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Parameter Estimates | β | (SE) | β | (SE) |

| Main Effects | ||||

| PR Economic hardship → AR Economic hardship | .22** | .02 | .24** | .02 |

| PR Economic hardship → Depressive symptoms T2 | .11 | .27 | .08 | .26 |

| PR Economic hardship → Risky behaviors T2 | .08 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| PR Economic hardship → GPA T2 | −.08 | .03 | −.03 | .03 |

| AR Economic hardship → Warmth | −.19** | .08 | −.26** | .10 |

| AR Economic hardship → Conflict | .36** | .09 | .31** | .08 |

| Warmth → Depressive symptoms T2 | −.19** | .76 | −.11* | .57 |

| Warmth → Risky behaviors T2 | −.13* | .03 | −.12* | .03 |

| Warmth → GPA T2 | .09 | .07 | .04 | .06 |

| Conflict → Depressive symptoms T2 | .20** | .76 | .22** | .67 |

| Conflict → Risky behaviors T2 | .30** | .03 | .17* | .03 |

| Conflict → GPA T2 | −.09 | .08 | −.18** | .07 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 → Depressive symptoms T2 | .24** | .07 | .24** | .07 |

| Risky behaviors T1 → Risky behaviors T2 | .46** | .06 | .50** | .07 |

| GPA T1 → GPA T2 | .55** | .06 | .53** | .06 |

| Covariate Estimatesb | ||||

| Gender → Depressive symptoms T1a | −.19** | 1.05 | −.19** | 1.07 |

| Gender → GPA T1 | −.14* | .11 | −.15* | .11 |

| Gender → Depressive symptoms T2 | −.28** | 1.01 | −.27** | 1.02 |

| Gender → Risky behavior T2 | .10* | .04 | .12* | .04 |

| Family Income → Risky Behaviors T2 | .16* | .07 | .16* | .09 |

| Covariance Estimates | ||||

| PR Economic hardship with Family income | −.51** | .06 | −.59** | .06 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 with Risky behaviors T2a | −.14** | .40 | −.13** | .40 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 with AR Economic hardshipa | .11 | .45 | .11 | .47 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 with PR Economic hardship | .26** | 1.61 | .26** | 1.69 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 with Family income | −.24** | .20 | −.23** | .19 |

| Depressive symptoms T1 with Conflicta | .14* | .46 | .20** | .52 |

| Risky behaviors T1 with Conflicta | .23* | .03 | .22* | .03 |

| Risky behaviors T1 with GPA T1 | −.34** | .03 | −.34** | .03 |

| Risky behaviors T1 with PR Economic hardship | .14 | .08 | .20* | .08 |

| Risky behaviors T1 with Family income | −.12 | .01 | .21 | .01 |

| GPA T1 with PR Economic hardship | −.20** | .15 | −.18** | .15 |

| GPA T1 with Family income | .21** | .02 | .21** | .02 |

| GPA T1 with Conflict | −.23** | .05 | −.22** | .05 |

| Conflict with Warmth | −.29** | .05 | −.05 | .05 |

| Depressive symptoms T2 with Risky behavior T2 | .08 | .14 | .15* | .16 |

| Depressive symptoms T2 with GPA T2 | .03 | .42 | .00 | .43 |

| Risky behavior T2 with GPA T2 | −.27** | .02 | −.29** | .02 |

Note. PR = Parent Report; AR = Adolescent report; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2;

p < .05;

p < .01.

model modification;

only significant covariate estimates are shown.

Figure 1.

Mediation model for mothers. Only significant paths (* p < .05; ** p < .01) are shown. Bolded lines represent significant mediation paths.

Tests of Indirect Effects

For adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship as an intervening variable, the following paths were tested and were significant: a) mothers’ perceptions of economic hardship to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to warmth with mothers (indirect effect = −.04, 95% CI = −.02, −.01); and b) mothers’ perceptions of economic hardship to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with mothers (indirect effect = .08, 95% CI = .01, .04).

For maternal warmth and conflict as intervening variables (controlling for Time 1 adjustment), the following paths were significant: a) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to warmth with mothers to depressive symptoms (indirect effect = .04, 95% CI = .19, 1.09); b) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with mothers to depressive symptoms (indirect effect = .07, 95% CI = .41, 1.80); and c) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with mothers to risky behaviors (indirect effect = .11, 95% CI = .03, .09). In contrast, the path from adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to warmth with mothers to risky behaviors was not significant.

Adolescent gender as a moderator

To test the moderating role of adolescent gender between adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and maternal warmth and conflict, the model was estimated with these additional interaction terms and was an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 (27) = 51.98, p < .01, χ2/df = 1.93, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .07); however, the interaction terms were not significant. Turning to the model including gender as a moderator of the paths from maternal warmth and conflict to adolescent adjustment, the model was a poor fit to the data, χ2 (36) = 112.65, p < .01, χ2/df = 3.13, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .09, and the interaction terms were not significant.

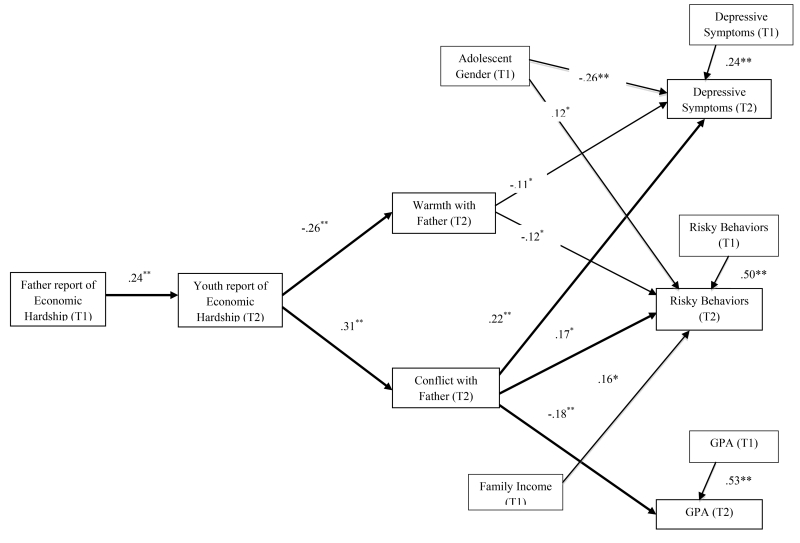

Model for Fathers

The model for fathers also was an adequate fit to the data, χ2 (21) = 37.79, p < .05, χ2/df = 1.75, CFI = 97, RMSEA = .06 (see Table 2; Figure 2). Similar to the findings for mothers, fathers’ perceptions of economic hardship were positively associated with adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship; adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship were negatively related to warmth with fathers and positively related to conflict with fathers; warmth with fathers significantly and negatively predicted depressive symptoms and risky behaviors, but not GPA; conflict with fathers significantly and positively predicted adolescents’ depressive symptoms and involvement in risky behaviors. Additionally, conflict with fathers significantly and negatively predicted GPA. As for the model for mothers, all Time 1 adjustment indices significantly predicted Time 2 adjustment. The direct paths between fathers’ perceptions of economic hardship and adolescent adjustment were not significant. The direct path from adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to depressive symptoms was significant, but the direct paths from adolescents’ perceptions of hardship to risky behaviors and GPA were not significant. As in the model for mothers, girls reported greater depressive symptoms and boys reported greater involvement in risky behaviors.

Figure 2.

Mediation model for fathers. Only significant paths (* p < .05; ** p < .01) are shown. Bolded lines represent significant mediation paths.

Tests of Indirect Effects

For adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship as an intervening variable, the following paths were tested and were significant: a) fathers’ perceptions of economic hardship to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to warmth with fathers (indirect effect = −.06, 95% CI = −.04, −.01); and b) fathers’ perceptions of economic hardship to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to paternal conflict (indirect effect = .08, 95% CI = .01, .04).

For paternal warmth and conflict as intervening variables (controlling for Time 1 adjustment), the following paths were significant: a) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with fathers to depressive symptoms (indirect effect = .07, 95% CI = .52, 1.58); b) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with fathers to risky behaviors (indirect effect = .05, 95% CI = .01, .05); and c) adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to conflict with fathers to GPA (indirect effect = −.05, 95% CI = −.13, −.03). Significance of an indirect effect was not found for the path from adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship to paternal warmth to depressive symptoms or risky behaviors.

Adolescent gender as a moderator

To test for adolescent gender as a moderator between adolescents’ reports of economic hardship and father-adolescent relationship qualities, the model was estimated with these additional interaction terms and was an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (27) = 46.99, p < .01, χ2/df = 1.74, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06. The model testing adolescent gender as a moderator of the link between father-adolescent relationship qualities and adolescent adjustment was also an acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (36) = 69.64, p < .01, χ2/df = 1.93, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06. However, the interactions terms were not significant.

Discussion

The present study extended research on how family economic hardship was linked to adolescent adjustment in several ways. First, this study demonstrated that adolescents’ perceptions of familial processes (i.e., economic hardship, parent-adolescent relationship quality) play an important role in the associations from parental economic hardship to adolescent adjustment. Second, our findings contribute to the understanding of adolescents’ relationships with mothers and fathers in times of economic stress, as fathers have been neglected relative to mothers in research on ethnic minority families (Parke & Buriel, 2006). Third, by examining two dimensions of parent-adolescent relationship quality and three aspects of youth adjustment, we provided insights about the specificity in dimensions of the parent-adolescent relationship that were associated with different aspects of adjustment under circumstances of hardship. At the broadest level, our findings suggest that adolescents’ cognitions about their families’ economic situations are a potentially important mechanism by which parent economic hardship is associated with adolescents’ adjustment.

This study provides evidence for the intervening effects of adolescents’ perceptions of family economic hardship between parent ratings’ of economic hardship and adolescents’ perceptions of warmth and conflict with mothers and fathers. As expected, mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of economic hardship were positively related to adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship, which, in turn, were related to adolescents’ perceptions of lower levels of warmth and higher levels of conflict with mothers and fathers. These findings are consistent with work supporting the family stress model in which economic hardship processes were linked to the nature of the parent-adolescent relationship (although not as perceived by adolescents; e.g., Benner & Kim, 2010) and previous models suggesting childhood stress leads to perceptions of lower relationship quality with others (e.g., Miller et al., 2011), but also with evidence of the important role of adolescents’ awareness of both stressors and family processes in understanding the linkages to adolescent adjustment (Harold & Conger, 1997). We echo the call of scholars (Bloom-Feshbach et al.,1982; Compas, 1987; Rutter, 1983) to consider children and adolescents’ perceived understanding of stressors to more fully understand how stressors progress in their lives, especially in adolescence, when the development of cognitive capacities leads to greater perspective-taking and awareness than in childhood (Keating, 2004).

We also found support for the intervening role of adolescents’ perceptions of parent-adolescent relationship qualities, a key family stress model component explaining adolescent adjustment in challenging economic circumstances (Conger et al., 2010). More specifically, we found adolescents who perceived greater family economic hardship were more likely to perceive less positive parent-adolescent relationships and, in turn, experience more symptoms of depression, higher participation in risky behaviors, and lower grades in school. It is notable that father-adolescent conflict explained the links between adolescent perceptions of hardship and all three indicators of adolescent adjustment, whereas maternal conflict explained links to depressive symptoms and risky behaviors, but not school performance. Our findings suggest that having disagreements or arguing with mothers and fathers is a salient mechanism of the risk of perceived economic hardship and a potentially important target of prevention and intervention efforts. Even though we controlled for prior adjustment, we are cautious in interpreting these findings as we assessed adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship, parent-adolescent relationship qualities, and youth adjustment at the same time point and thus, do not provide evidence of causation. Longitudinal work that includes multiple assessments of these constructs will provide clearer understanding of the direction of effects.

Prior research documenting differences in mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with their adolescents in Latino families (Crockett et al., 2007; Parke & Buriel, 2006) led us to consider mother-adolescent and father-adolescent relationship qualities in separate models. As described above, slightly different patterns emerged for parent-adolescent conflict; however, with regard to parent-adolescent warmth, maternal warmth was linked to depressive symptoms, but not to risky behaviors or school performance, and there were no intervening effects of paternal warmth on any of the associations to adolescent adjustment. Mothers are more likely to be the primary caregiver in Mexican American families and, in that role, have open communication with their children (Crockett et al., 2007). Thus, close emotional ties with mothers may play a protective role in adolescents’ depressive symptoms. In examining the links between family context and adolescent adjustment, an important next step will be to test the intervening roles of mother-adolescent and father-adolescent relationship qualities in families with different structures (e.g., father-absent, mother-absent).

Some prior work suggests that economic hardship may differentially impact girls versus boys (Elder & Caspi, 1998; McLoyd, 1989). In this sample, however, our findings suggested that the links between perceived economic hardship and parent-adolescent relationship qualities were similar for Mexican-origin girls and boys. Given the emphasis on family in Mexican culture (Hardway & Fuligni, 2006; García-Coll & Vázquez García, 1995), family hardship may be associated with both girls’ and boys’ family relationships. It is important to note, however, that our findings are specific to middle adolescence. Had we examined the moderating role of gender in early adolescence, we may have found more pronounced differences (Hill & Lynch, 1983). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine Mexican-origin adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship and the associations to their perceptions of parent-adolescent relationship quality. Future work examining these associations, particularly at different stages in adolescence, will be important.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of this study provide valuable insight for future work aimed at delineating the mediating processes linking family economic hardship to adolescent adjustment. Importantly, our study focused on Mexican-origin adolescents, a young, large, and rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population who are, on average, at increased risk for experiencing poverty, economic hardship (US Census Bureau, 2010a), and adjustment difficulties (Wilkinson et al., 2011, U.S. Census Bureau, 2010b). Thus, identifying targets for prevention with this population has significant public health implications. Our research has limitations, however, that provide directions for future research.

First, future work needs to examine changes in adolescents’ perceived economic hardship, parent-adolescent relationship qualities, and adjustment across time to better understand the directions of effects and the interrelations of these processes over time and across different developmental periods. Second, our findings take a first step in describing the process of Mexican American families’ economic hardship from adolescents’ perspectives, but our sample is composed of two-parent predominantly immigrant families living in the southwest. Additionally, our response rate was modest, and thus, the replication of these findings will be important. In addition, it will be important to examine these mechanisms in samples from different geographic locations and with different immigration histories and family structures (e.g., single- and step-parent families). Third, a strength of this study is that we examined economic hardship processes from adolescents’ perspectives using a prospective design; however, our findings are based primarily on adolescents’ ratings of Time 2 constructs. Future work should include the perspectives of multiple family members to better understand how economic hardship has implications for family relationship dynamics and individual adjustment. Finally, although examining familism values was beyond the scope of our study, future research should consider how values play a role in adolescents’ perceptions of stress given the heightened interdependence in Mexican-origin families (e.g., Hardway & Fuligni, 2006).

Implications

Economic hardship is of concern for families in society today (Cauthen & Fass, 2009). Poverty, stagnant incomes, and the decline in economic mobility, or the decreasing likelihood of moving from one income group to the next, are trends that have detrimental consequences for families and children. These hardships extend to two-parent Latino families (e.g., more than 50% of Latino adolescents with married parents live in low-income families). Within our sample, adolescents’ perceptions of economic hardship were fairly low, yet, meaningful enough to be significantly and strongly associated with qualities of the parent-adolescent relationship and, in turn, with adolescent adjustment. Given the potential malleability of the parent-adolescent relationship, it may be important to focus on mother- and father-adolescent relationship dynamics as a point of intervention in programs designed to support economically distressed families. Intervention programs designed to strengthen adolescents’ ties to their parents and lessen the conflict between them also can provide tests of the theoretical underpinnings of family stress process models, such that via better relationships with their parents, adolescents’ negative outcomes from their experiences with family economic stress will be ameliorated.

In designing interventions for Mexican-origin families with adolescents receiving government financial assistance, future work can consider targeting parent-adolescent warmth and conflict, as our findings suggest that more warmth and less conflict is associated with more positive adolescent adjustment across different domains. The evidence from this study indicates that better mental health, fewer risky behaviors, and better school performance are within the realm of possible benefits. All in all, culturally sensitive interventions that address Mexican-origin families’ economic hardship need to consider the significance of adolescents’ relationships with both their mothers and their fathers in promoting healthy adjustment among this large and rapidly increasing group of adolescents in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 (Kimberly A. Updegraff, Principal Investigator) and the Cowden Fund to the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics. We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Siena, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Susan McHale, Ann Crouter, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Jennifer Kennedy, Leticia Gelhard, Emily Cansler, Shawna Thayer, Devon Hageman, Ji-Yeon Kim, Lilly Shanahan, Norma Perez-Brena, Sue Annie Rodriguez, Chun Bun Lam, Megan Baril, Anna Soli, and Shawn Whiteman for their assistance in conducting this investigation.

Contributor Information

Melissa Y. Delgado, Department of Family and Child Development, Texas State University-San Marcos

Sarah E. Killoren, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Missouri

Kimberly A. Updegraff, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

References

- Azmitia A, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the ‘‘path of life’’ of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Praeger Press; Westport, CT: 2000. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera MB, Caples H, Tein JY. The psychological sense of economic hardship: Measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:493–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1010328115110. doi: 10.1023/A:1010328115110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Understanding Chinese American adolescents’ developmental outcomes: Insights from the family stress model. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00629.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom-Feshbach S, Bloom-Feshbach J, Heller K. Work, family, and children’s perceptions of the world. In: Kamerman S, Hayes C, editors. Families that work: Children in a changing world. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1982. pp. 268–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Praeger Press; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cauthen NK, Fass S. 10 important questions about child poverty and family economic hardship. Columbia University, National Center for Children in Poverty; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surveillance summaries, June 9. MMWR. 2006;55(SS-5) [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S, Parke R, Schofield T, Tsuha S, Chavez M, Lio S. Mexican American families and poverty. In: Crane D, Heaton T, editors. Handbook of families & poverty. SAGE Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks: 2008. pp. 161–181. Retrieved from http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/hdbk_familypoverty/SAGE.xml. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Stress and life events during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review. 1987;7:275–302. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(87)90037-7. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Families. 2002;64:361–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Brown J, Russell ST, Shen Y. The meaning of good parent-child relationships for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:639–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00539. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Conger KJ, McAdams KK, Neppl TK. Personal characteristics and resilience to economic hardship and its consequences: Conceptual issues and empirical illustrations. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1645–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00596.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber B. Risky behavior measure. University of Michigan; 1990. Unpublished scale. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Lord S, Roeser RW. Round holes, square pegs, rocky roads, and sore feet: A discussion of stage-environment fit theory applied to families and school. In: Cichetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology, volume VII: Adolescence: Opportunities and challenges. University of Rochester Press; Rochester, NY: 1996. pp. 47–92. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G,H,, Jr, Caspi A. Economic stress in lives: Developmental perspectives. Journal of Social Issues. 1988;44:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.824. [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Martinez CR. Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:214–226. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2402_9. [Google Scholar]

- García-Coll C, Vazquez García HA. Hispanic children and their families. In: Fitzgerald HE, Lester BM, B Zuckerman, editors. Children and Poverty: Research, Health, and Policy Issues. Garland; New York: pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RMB, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Saenz D. Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:447–466. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardway C, Fuligni AJ. Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1246–1258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Conger RD. Marital conflict and adolescent distress: The role of adolescent awareness. Child Development. 1997;68:333–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01943.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A, editors. Girls at Puberty: Biological and Psychosocial Perspectives. Plenum; New York: 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Keating DP. Cognitive and brain development. In: Lerner RJ, Steinberg LD, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 2nd ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. pp. 45–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Virdin LM, Roosa M. Socialization and Family Correlates of Mental Health Outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American Children: Consideration of Cross-Ethnic Scalar Equivalence. Child Development. 1994;65:212–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VG, Socialization and development in a changing economy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.293. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Jayaratne TE, Ceballo R, Borquez J. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development. 1994;65:562–589. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00769.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Benner AD, Tan CS, Kim SY. Family economic stress and academic well-being among Chinese-American youth: The influence of adolescents’ perceptions of economic strain. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:279–290. doi: 10.1037/a0015403. doi: 10.1037/a0015403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 429–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Penilla C, Pantoja P. Acculturation, parent-adolescent conflict, and adolescent adjustment in Mexican American families. Family Process. 2006;45:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00081.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;7:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Stress, coping, and development: Some issues and some questions. In: Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, coping, and development in children. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1983. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype-environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Martin MJ, Conger KJ, Neppl TM, Donnellan MB, Conger RD. Intergenerational transmission of adaptive functioning: A test of the interactionist model of SES and human development. Child Development. 2011;82:33–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01539.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry LM, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. doi:10.2307/1129734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Concepts of self and social convention: Adolescents and parents’ reasoning about hypothetical and actual family conflicts. In: Gunnar MR, Collins WA, editors. Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology, Vol. 21: Development during the transition to adolescence. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 79–122. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents, families, and social development: How adolescents construct their worlds. Wiley-Blackwell, Inc.; West Sussex, England: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Crouter AC. The nature and correlates of Mexican-American adolescents’ time with parents and peers. Child Development. 2006;77:1470–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00948.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Selected Economic Characteristics: 2006-2010 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables. 2010a Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_SF4_DP03&prodType=table.

- U.S. Census Bureau Educational attainment by race and Hispanic origin. 2010b Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/education/educational_attainment.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau Facts for features: Cinco de Mayo: March 2012. U.S. Census Bureau News. 2012 Mar; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb12-ff10.html.

- Wadsworth ME, Compas BE. Coping with family conflict and economic strain: The adolescent perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:243–274. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00033. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson AV, Shete S, Spitz MR, Swann AC. Sensation seeking, risk behaviors, and alcohol consumption among Mexican Origin Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]