Abstract

Objective

: To determine the prevalence of alternative diagnoses based on chest CT angiography (CTA) in patients with suspected pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) who tested negative for PTE, as well as whether those alternative diagnoses had been considered prior to the CTA.

Methods

: This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study involving 191 adult patients undergoing CTA for suspected PTE between September of 2009 and May of 2012. Chest X-rays and CTAs were reviewed to determine whether the findings suggested an alternative diagnosis in the cases not diagnosed as PTE. Data on symptoms, risk factors, comorbidities, length of hospital stay, and mortality were collected.

Results

: On the basis of the CTA findings, PTE was diagnosed in 47 cases (24.6%). Among the 144 patients not diagnosed with PTE via CTA, the findings were abnormal in 120 (83.3%). Such findings were consistent with an alternative diagnosis that explained the symptoms in 75 patients (39.3%). Among those 75 cases, there were only 39 (20.4%) in which the same alterations had not been previously detected on chest X-rays. The most common alternative diagnosis, made solely on the basis of the CTA findings, was pneumonia (identified in 20 cases). Symptoms, risk factors, comorbidities, and the in-hospital mortality rate did not differ significantly between the patients with and without PTE. However, the median hospital stay was significantly longer in the patients with PTE than in those without (18.0 and 9.5 days, respectively; p = 0.001).

Conclusions

: Our results indicate that chest CTA is useful in cases of suspected PTE, because it can confirm the diagnosis and reveal findings consistent with an alternative diagnosis in a significant number of patients.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism/diagnosis, Pulmonary embolism/epidemiology, Angiography

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are part of the spectrum of venous thromboembolism. The annual incidence of PTE is 100-200 cases/100,000 population,( 1 , 2 ) and the overall 30-day mortality rate ranges from 6.7% to 11.0%,( 3 - 5 ) reaching 30.0% in the absence of treatment.( 6 ) Autopsy-based studies suggest that these figures are underestimated.( 7 ) The underdiagnosis of PTE might be due, at least in part, to the wide variability in the clinical presentation of PTE and to the fact that the findings are often nonspecific. The clinical findings consistent with suspected PTE are dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, and tachypnea that have an acute onset. In situations that are more dramatic, in which much of the pulmonary circulation is affected or there is a history of significant cardiopulmonary disease, there can be signs of clinical instability, such as hypotension, signs of low cardiac output, and significant hypoxemia.( 8 ) The presence of risk factors for PTE in combination with a suggestive clinical picture reinforces the clinical suspicion of PTE.

The clinical suspicion of PTE should be investigated by specific tests that vary according to the clinical status of the patient. The use of chest CT angiography (CTA) has increased sharply in recent years, and this imaging test has been used as the first-line tool for suspected cases of PTE in various institutions.( 9 - 11 ) A safe, noninvasive imaging test that allows direct detection of the intra-arterial pulmonary thrombus, CTA is rapidly performed, results generally being available within 24 h. Reported rates of CTA sensitivity range from 64% to 100%, whereas those of CTA specificity range from 89% to 100%.( 12 - 14 ) Chest CTA results are positive for PTE in 6.6-60.0%, depending on the criteria used for CTA referral.( 9 , 15 - 21 )

In parallel with the recognition of the importance of chest CTA in the diagnosis of PTE, its excessive and sometimes unnecessary use raises concerns about cost-effectiveness issues and about adverse effects related to intravenous contrast use and high radiation rates.( 22 ) A potential advantage of CTA is identification of an alternative diagnosis when no findings of PTE are detected. Alternative diagnoses, such as pneumonia, cancer, pleural effusion, heart failure, COPD exacerbation, etc., or incidental findings, such as benign nodules, adenopathy, and granulomatous disease scarring, have been reported in 25.4% to 70.0% of chest CTA results. ( 9 , 15 - 21 ) The risks, benefits, and costs associated with the investigation of such findings need to be further elucidated, given that the investigation has therapeutic consequences in less than 5% of cases. ( 20 ) In addition, the role played by chest CTA in the absence of PTE in making alternative diagnoses that were missed by simple tests, such as chest X-ray, has not been fully investigated.( 18 - 20 )

The objective of the present study was to investigate the contribution of chest CTA findings to identifying alternative diagnoses to PTE that would explain the clinical picture of the patient and that were missed on chest X-ray.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study carried out in the Department of Radiology of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), a general university hospital located in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil. The HCPA has an operational capacity of 845 beds, of which 87 are ICU beds and 47 are ER beds; there are also 35 operating rooms. In 2012, the HCPA had 33,585 admissions and 594,942 outpatient visits. The HCPA uses an online medical record system (known as the Hospital Management Applications Web) that was developed in-house and, in September of 2009, was integrated into the Radiology Information System and into a system for the management and storage of medical images (Picture Archiving and Communication System). In parallel, an image and information management system (IMPAX(r); Agfa HealthCare, Mortsel, Belgium) was employed as a technological option for performing the tasks of transmission, storage, and retrieval of medical images.

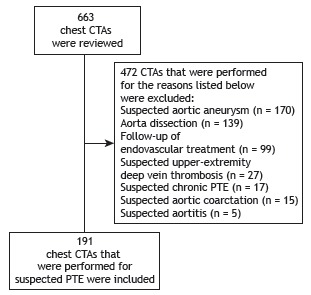

The study was approved by the HCPA Research Ethics Committee. Given the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was not required. The authors signed a confidentiality agreement for the use of data. Between September of 2009 and May of 2012, 663 chest CTAs were performed for various reasons. We included all cases involving adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) referred to the Computed Tomography Division of the HCPA for chest CTA for suspected PTE. We excluded cases referred from the outpatient clinic for investigation of chronic pulmonary hypertension, as well as cases in which chest CTA was ordered for reasons other than the investigation of PTE (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the patients included in the study. CTA: CT angiography; and PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

Patient demographic and clinical data, such as age, gender, race, smoking history, symptoms at the time of suspicion of PTE, presence of risk factors for PTE, and comorbidities, as well as the health care setting from which the patient was referred at the time of suspicion, length of hospital stay, and clinical outcome (discharge or death), were obtained from the electronic medical records of the HCPA. The medical records were reviewed for the presence of clinical pretest probability scores for PTE. The Geneva score, in its original version,( 8 ) was calculated retrospectively.( 8 )

Chest CTA images were obtained with a 16-detector helical CT scanner (Brilliance(r) CT; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). All images were viewed on a workstation, with the image storage and transmission systems mentioned above, by two independent radiologists, trained to interpret CTAs. Discordant interpretations were resolved by consensus.

Chest CTAs were classified as positive, negative, or inconclusive for PTE. Scans were considered positive for PTE if they revealed filling defects within the pulmonary artery or any of its branches. For positive scans, PTE was classified as central (up to the first branch of the segmental artery), peripheral (beyond the first branch of the segmental artery), or diffuse (central and peripheral). In the presence of adequate opacification of the pulmonary vascular bed, with no filling defects, scans were considered negative for PTE. All CTAs were reviewed for the presence of other abnormal pulmonary and extrapulmonary findings.

Alternative diagnoses were reviewed on the basis of clinical and imaging findings, by two pulmonologists. Findings suggestive of an alternative diagnosis were defined as CTA abnormalities that could explain the symptoms (such as dyspnea, chest pain, hypoxemia, and tachycardia). The following criteria were used to establish the alternative diagnoses: 1) pneumonia-presence of cough, expectoration, and systemic findings (tachycardia, leukocytosis or leukopenia, and fever) associated with new pulmonary infiltrate; 2) decompensated heart failure-a clinical diagnosis of heart failure and radiological signs of heart enlargement and pulmonary edema or pleural effusion; 3) pleural effusion due to other causes-signs of at least moderate pleural effusion that was not associated with heart failure; 4) lymphangitic carcinomatosis or progression of cancer-a histological diagnosis of lung cancer with radiological signs of interstitial involvement (with or without pleural effusion or enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes) or an increase in the lung tumor relative to the previous scan; 5) noncardiogenic pulmonary edema-radiological signs of pulmonary edema, including interstitial infiltrate, confluent consolidation, ground-glass attenuation associated with septal thickening, and/or unilateral or bilateral pleural effusion, in the absence of heart failure and in the presence of one or more conditions that explained the edema; 6) connective tissue disease-related lung disease-a previous diagnosis of connective tissue disease (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or systemic sclerosis) with pleural and pulmonary involvement attributed to the connective tissue disease itself, including interstitial pulmonary infiltrate, consolidation, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusion, and pulmonary hypertension; and 7) atelectasis-signs of atelectasis (opacity and reduced lung volume) of at least one lung lobe, with significant ventilatory impairment. In addition, we reviewed the respective chest X-rays, together with the chest X-ray reports and the related notes contained in the medical records, and we determined whether the same alterations had been previously detected on chest X-rays.

Taking into account the prevalence of alternative diagnoses made on the basis of chest CTA findings in previous studies( 9 , 15 - 21 ) and the high prevalence of tuberculosis in Brazil, we calculated that, in order to obtain an expected proportion of alternative diagnoses of 60% and achieve a power of 80%, at a level of significance of 5% (two-tailed test), the sample size would have to be 188 patients.

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative data were presented as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range. The prevalence of PTE, abnormal CTA findings, and alternative diagnoses was expressed as absolute numbers or as absolute numbers and proportions. The groups of patients with and without PTE were compared with the independent sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, depending on data distribution. Categorical variables were compared with Pearson's chi-square test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 191 patients were included in the study. The mean age was 59.3 ± 17.1 years, and women predominated. Of those, 113 patients (59.2%) were referred from the emergency room at the time of suspicion, whereas 71 (37.2%) were referred from the ward and 7 (3.7%) were referred from the ICU. The major clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of 191 patients undergoing CT angiography for suspected pulmonary thromboembolism.a .

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.3 ± 17.1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 128 (67.0) |

| Female | 63 (33.0) |

| White race | 169 (88.5) |

| Smoking history | 89 (46.6) |

| Smoking history, pack-yearsb | 59.3 ± 17.1 |

| Health care setting where the suspicion was raised | |

| Emergency room | 113 (59.2) |

| Ward | 71 (37.2) |

| ICU | 7 (3.7) |

aValues expressed as n (%) or mean ± SD. bn = 78

The demographics, symptoms, risk factors, comorbidities, length of hospital stay, and survival of the 191 patients are shown in Table 2, stratified by the presence (n = 47) or absence (n = 144) of PTE. The most common clinical complaints leading to referral for CTA in the 191 patients were sudden dyspnea, in 75.4%; chest pain, in 33.0%; and cough, in 25.1%. Less common complaints were anxiety (in 9.4%), syncope (in 6.3%), and hemoptysis (in 3.1%), there being no difference between the groups with and without PTE (6.4% vs. 2.1%; p > 0.05). The most common risk factors for PTE were cancer and previous hospitalization. The most common comorbidities were systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes, COPD, and previous stroke. There were no significant differences in demographic variables, symptoms, or risk factors between the patients with and without PTE (p > 0.05). There was a trend toward a higher prevalence of PTE in patients in whom suspicion was raised in the ward than in those in whom suspicion was raised in the emergency room (31.0% vs. 21.6%; p = 0.09). Patients with PTE had longer hospital stays than did those without (median: 18 days vs. 9.5 days; p = 0.0001). Among the 191 patients, mortality was 13.6%, being 12.8% and 13.9% in the groups with and without PTE, respectively (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Comparison of characteristics between patients with positive and those with negative CT angiography results for pulmonary thromboembolism.a .

| Characteristic | All patients | Patients with positive CTA results for PTE | Patients with negative CTA results for PTE |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 191) | (n = 47) | (n = 144) | |

| Age, yearsb | 59.3 ± 17.1 | 60.3 ± 17.2 | 58.9 ± 17.2 |

| Female gender | 128 (67.0) | 28 (59.6) | 100 (69.4) |

| Smoking | 89 (46.6) | 18 (38.3) | 71 (49.3) |

| Symptoms | |||

| Sudden dyspnea | 144(75.4) | 36 (76.6) | 108 (75) |

| Chest pain | 63 (33) | 17 (36.2) | 46 (31.9) |

| Cough | 48 (25.1) | 11 (23.4) | 37 (25.6) |

| Expectoration | 27 (14.1) | 7 (14.9) | 20 (13.9) |

| Anxiety | 18 (9.4) | 3 (6.4) | 15 (10.4) |

| Syncope | 12 (6.3) | 5 (10.6) | 7 (4.9) |

| Hemoptysis | 6 (3.1) | 3 (6.4) | 3 (2.1) |

| Risk factors | |||

| Cancer | 49 (25.7) | 9 (19.1) | 40 (27.8) |

| Hospital admission in the last 3 months | 48 (25.1) | 10 (21.3) | 38 (26.4) |

| Being bedridden for more than 3 days | 31 (16.2) | 6 (12.8) | 25 (17.4) |

| Obesity | 31 (16.2) | 9 (19.1) | 22 (15.3) |

| Decompensated heart failure | 28 (14.7) | 5 (10.6) | 23 (16.0) |

| COPD exacerbation | 16 (8.4) | 3 (6.4) | 13 (9.0) |

| Recent surgery | 25 (13.1) | 9 (19.1) | 16 (11.1) |

| Previous DVT | 13 (6.8) | 4 (8.5) | 9 (6.3) |

| Previous PTE | 11 (5.8) | 2 (4.3) | 9 (6.3) |

| Intravenous catheter | 9 (4.7) | 1 (2.1) | 8 (5.6) |

| Paralysis of the lower limbs | 4 (2.1) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (1.4) |

| Fracture | 4 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (2.1) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 89 (46.6) | 24 (51.1) | 65 (45.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (20.1) | 12 (25.5) | 27 (18.8) |

| COPD | 35 (18.3) | 6 (12.8) | 29 (20.1) |

| Stroke | 28 (14.7) | 9 (19.1) | 19 (13.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 19 (9.9) | 4 (8.5) | 15 (10.4) |

| Thyroid disease | 17 (8.9) | 4 (8.5) | 13 (9.0) |

| Renal failure | 14 (7.3) | 3 (6.4) | 11 (7.6) |

| Diffuse connective tissue disease | 13 (6.8) | 2 (4.3) | 11 (7.6) |

| Asthma | 9 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (6.3) |

| Outcomes | |||

| Length of hospital stay, daysc | 11.0 (4-22) | 18.0 (8-35) | 9.5 (3-19)* |

| Death | 26 (13.6) | 6 (12.8) | 20 (13.9) |

CTA: CT angiography; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; and DVT: deep vein thrombosis. aValues expressed as n (%). bValues expressed as mean ± SD. cValues expressed as median (interquartile range). *p = 0.0001; other results, p > 0.05.

An objective, systematic evaluation of pretest probability of PTE, using a clinical score, was found in 14 of the 191 medical records (7.3%). The Geneva score, calculated retrospectively, was 5.9 ± 3.2 points in the patients with PTE and 5.0 ± 2.6 in the patients without PTE (p = 0.06). In a three-level stratification of clinical risk probability, 26.2% of the patients were classified as having low risk, 70.2% were classified as having intermediate risk, and 3.7% were classified as having high risk. There were no significant differences in risk stratification between the patients with and without PTE (p = 0.07).

A review of the chest CTAs identified six scans of poor technical quality. However, those six allowed a conclusive interpretation. Abnormal findings were observed in 167 cases. A diagnosis of PTE was made in 47 patients (24.6%), and, in most cases, the thrombi were peripheral, being located either on the right side or bilaterally (Table 3). Among the 47 patients with PTE, 31 had other abnormal findings on CTA. The most common findings were atelectasis, in 31.9%; pleural effusion, in 25.5%; consolidation, in 17.0%; enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, in 14.9%; pulmonary nodules, in 12.8%; and enlarged cardiac silhouette, in 6.4%.

Table 3. Chest CT angiography results in 191 patients with suspected pulmonary thromboembolism.

| Finding | Patients |

|---|---|

| Confirmed pulmonary thromboembolism | 47 |

| Type of involvement | |

| Peripheral | 31 |

| Central | 13 |

| Mixed | 3 |

| Location | |

| Right-sided | 22 |

| Bilateral | 20 |

| Left-sided | 5 |

| Unconfirmed pulmonary thromboembolism | 144 |

| Normal results | 24 |

| Abnormal findings | 120 |

| Findings unrelated to the alternative diagnosis | 45 |

| Findings suggestive of an alternative diagnosis* | 75 |

| Findings also present on chest X-ray | 36 |

| Findings on CT angiography only | 39 |

*The findings explain the patient's symptoms.

Among the 144 CTA scans that were negative for PTE, 24 were considered completely normal, 21 revealed one abnormality, and 99 revealed multiple findings. The most common findings were atelectasis, in 48.6% of the cases; pulmonary nodules, in 30.6%; pleural effusion, in 29.9%; consolidation, in 21.5%; and emphysema, in 21.5%. Extrathoracic abnormalities were less common (Table 4).

Table 4. Abnormal findings in 144 patients with negative CT angiography results for pulmonary thromboembolism.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Findings in the chest | ||

| Atelectasis | 70 | 48.6 |

| Pulmonary nodules | 44 | 30.6 |

| Pleural effusion | 43 | 29.9 |

| Consolidation | 31 | 21.5 |

| Emphysema | 31 | 21.5 |

| Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes | 29 | 20.1 |

| Enlarged cardiac silhouette | 29 | 20.1 |

| Calcified nodules | 22 | 15.3 |

| Ground-glass infiltrate | 12 | 8.3 |

| Micronodules | 9 | 6.3 |

| Pericardial effusion | 9 | 6.3 |

| Interstitial infiltrate | 8 | 5.6 |

| Vertebral or rib fracture | 8 | 5.6 |

| Pleural plaques | 6 | 4.2 |

| Elevated hemidiaphragm | 3 | 2.1 |

| Extrathoracic findings | ||

| Hiatal hernia | 4 | 2.8 |

| Thyroid nodule | 3 | 2.1 |

| Enlarged axillary lymph nodes | 3 | 2.1 |

| Findings suggestive of pancreatitis | 2 | 1.4 |

Among the 120 CTA scans that were negative for PTE and revealed abnormal findings, there were 75 that were consistent with an alternative diagnosis that explained the clinical picture of the patient. However, among those cases, there were only 39 (20.4%) in which the same alterations had not been previously detected on chest X-rays (Table 3). The major diagnoses made on the basis of CTA, in the absence of chest X-ray abnormalities, are shown in Table 5. Thirty-one patients had pulmonary abnormalities, and 8 had cardiac abnormalities. The most prevalent diagnosis was pneumonia, identified in 20 cases.

Table 5. Alternative diagnoses made solely on the basis of the chest CT angiography findings.

| Diagnosis | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 20 | 51.2 |

| Decompensated heart failure | 8 | 20.5 |

| Pleural effusion due to other causes | 4 | 10.3 |

| Lymphangitic carcinomatosis/progression of cancer | 3 | 7.7 |

| Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema | 2 | 5.1 |

| Connective tissue disease-related lung disease | 1 | 2.6 |

| Atelectasis | 1 | 2.6 |

| Total | 39 | 100.0 |

DISCUSSION

Our study assessed 191 consecutive CTAs that were performed for suspected PTE, and the major findings were as follows: 1) the prevalence of PTE was 24.6%; 2) clinical complaints, risk factors, comorbidities, and the proportion of deaths were similar between the groups with positive and negative CTA results for PTE; however, length of hospital stay was longer for the former group; and 3) findings consistent with an alternative diagnosis that explained the patient's symptoms were detected on the CTA scans that were negative for PTE in 39.3% of the cases, although that proportion dropped to 20.4% when only the findings that had not been previously detected on chest X-rays were taken into account.

The prevalence of PTE in our study was comparable to that seen in other studies (19.0-24.3%),( 11 , 20 , 21 , 23 ) but it was higher than that reported by other authors (8.6-9.5%).( 16 , 18 , 24 ) Factors such as level of clinical suspicion and compliance with guidelines for the investigation of PTE can affect the prevalence rate of the disease. An objective, systematic evaluation of pretest probability of PTE was described in only 7.3% of the medical records in the present study. In a recent study reviewing 641 chest CTAs, the prevalence of PTE diagnosed by chest CTA was relatively low (9.5%). A careful review conducted by those authors showed that, in 90 cases in their study, the patients had a low probability of having PTE (D-dimers < 500 ng/mL, and Well's score ≤ 4), and there was no formal indication for investigation by CTA. Only two of those patients had PTE.( 18 ) In parallel, a high rate of positive CTA results for PTE might reflect a low clinical suspicion of PTE. Therefore, in addition to assessing the prevalence of PTE, it is important to assess the degree of adherence to the diagnostic algorithm proposed by guidelines for the management of PTE.( 8 , 25 ) Although the degree of adherence to the institutional protocol for the investigation of PTE was not assessed in our study, our prevalence data are similar to those reported in another study (23.3%).( 26 )

The symptoms and signs of PTE are well known. Dyspnea, chest pain, and cough were the major symptoms reported by the patients with suspected PTE in our study, with no difference between patients with positive and those with negative CTA results for PTE, suggesting that the symptoms are not specific to PTE. The same symptoms appear as the most common in other studies( 9 , 27 ); however, the frequency of pleuritic pain and cough was higher in one such study (76% and 44%, respectively),( 27 ) and the frequency of cough was lower in the other such study (10.8%).( 9 ) In another study, chest pain was the most common symptom (in 41.4%), and dyspnea was observed in only 10% of the patients.( 24 ) The large discrepancy among the findings of various studies might, at least in part, be associated with symptom recording, given that, in retrospective studies, such as the last aforementioned one,( 24 ) the complaints might have been underestimated. The prevalence of hemoptysis in the patients in our study is within the range of prevalence levels reported in other previous studies of patients with PTE (1.9%-6.0%).( 4 , 9 , 18 , 23 , 27 )

A history of cancer, previous hospitalization, and being bedridden were the major risk factors for PTE in our study, having also been reported by other authors. ( 9 ) Recent surgery was the seventh most common risk factor in our sample (identified in 13.1%), although this proportion is comparable to those reported in two studies (11.8% and 14.4%)( 26 , 28 ) but lower than that reported in another study.( 18 ) The lower proportion of postoperative patients in our study might be associated with the source of the cases, given that most patients were referred from the emergency room.

Although risk factors and comorbidities were highly prevalent in our study, there were no significant differences between the groups with positive and negative CTA results for PTE. Likewise, there was no difference in mortality between the two groups. The in-hospital mortality among the patients with positive CTA results for PTE in our study was 12.8%, ranging from 6.4% to 11.4% in other studies.( 3 - 5 ) However, the patients with positive CTA results for PTE had longer hospital stays than did those with negative CTA results for PTE. Although PTE per se can extend the length of hospital stay, it can also be a marker of the severity of the patient's status, which is associated with hospital stay.

The proportion of normal CTA results in our study was 12.6%; in other studies, that proportion ranged from 12.5% to 29.3%.( 18 , 21 , 23 ) In our study, the major abnormal findings on the CTA scans that were negative for PTE were atelectasis, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusion, consolidation, and emphysema. Of note is the significant proportion of nodules and micronodules in our study relative to those reported in other studies,( 16 , 18 , 20 , 23 , 24 ) which might be related to the high prevalence of granulomatous diseases in Brazil.( 29 ) Such incidental findings, which were not associated with the patient's acute status, often might require further investigation or long-term follow-up.( 18 , 20 )

We assessed the clinical relevance of abnormal CTA findings to establishing an alternative diagnosis in the cases with negative CTA results for PTE. Such findings confirmed an alternative diagnosis, which explained the patient's symptoms, in 39.3% of the cases in our study (14.3-33.0% of the cases in other studies).( 16 , 18 - 21 ) However, in 20.4% of those cases, the confirmatory findings were identified only on CTAs, i.e., the same alterations had not been previously detected on chest X-rays. To our knowledge, only three studies have taken into account concurrent chest X-ray findings in the analysis of alternative diagnoses. In one study, an alternative diagnosis was established on the basis of CTA findings in 33% of the cases; however, in approximately half of those cases, the same alterations had already been detected on chest X-rays.( 16 ) Another group of authors identified an alternative diagnosis in 14.3% of the patients, chest X-rays having revealed the same findings in 9.8% of the cases.( 18 ) In addition, in another study, CTA revealed findings that supported an alternative diagnosis in 28% of 203 patients, findings being unsuspected prior to CTA in only 8.8% of the cases.( 20 ) Pneumonia was the most common alternative diagnosis in our and other studies,( 18 , 20 , 21 ) whereas pleural effusion predominated in two other studies.( 16 , 19 )

Some limitations of our study must be taken into account. This was a single-center study, which limits generalizability of results, and data collection was retrospective. Retrospective studies are at risk of selection bias (cases lost to follow-up) and measurement bias (data obtained from medical records). However, the sequential way in which the cases in our study were selected from the records of all CTAs performed in the institution minimized the risk of selection bias. An additional limitation is that patient follow-up was conducted only during hospitalization, providing only data on in-hospital mortality and no data on mid- or long-term survival. In contrast, a positive aspect of the study is that the imaging tests were interpreted by two independent radiologists experienced in interpreting CTAs. In addition, all cases with negative CTA results for PTE were reviewed by two pulmonologists, both from a clinical and radiological standpoint, and a consensus opinion was reached. This allowed increased diagnostic accuracy.

In conclusion, chest CTA was positive for PTE in 24.6% of the cases. Clinical findings and in-hospital mortality did not differ between the groups of patients with and without PTE, but length of hospital stay was longer in the patients with positive CTA results for PTE. Abnormal findings were detected in a large number of CTAs, and such findings were consistent with an alternative diagnosis that explained the clinical picture of the patient in 39.3% of the cases. However, in approximately half of those cases, the same alterations had already been detected on chest X-rays. In summary, our results indicate that chest CTA is useful in cases of suspected PTE, because it can confirm the diagnosis and reveal findings consistent with an alternative diagnosis in a significant number of patients.

Footnotes

Study carried out at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre e no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Pneumológicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre (RS) Brasil.

Financial support: This study received financial support from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS, Foundation for the Support of Research in the State of Rio Grande do Sul).

REFERENCES

- 1.Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Dis. 2008;28(3):370–372. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, Arcelus JI, Bergqvist D, Brecht JG. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(4):756–764. doi: 10.1160/th07-03-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Auble TE, Perrier A, Cornuz J. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(2):169–175. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casazza F, Becattini C, Bongarzoni A, Cuccia C, Roncon L, Favretto G. Clinical features and short term outcomes of patients with acute pulmonary embolism. The Italian Pulmonary Embolism Registry (IPER) Thromb Res. 2012;130(6):847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.08.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) Lancet. 1999;353(9162):1386–1389. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KI, Müller NL, Mayo JR. Clinically suspected pulmonary embolism: utility of spiral CT. Radiology. 1999;210(3):693–697. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr01693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, Agnelli G, Galiè N, Pruszczyk P. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2008;29(18):2276–2315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galiè N. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(43):3033-69, 3069a-3069k. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra S, Sarkar PK, Chandra D, Ginsberg NE, Cohen RI. Finding an alternative diagnosis does not justify increased use of CT-pulmonary angiography. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:9–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, Maître S, Girard P, Leroyer C. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: A prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1914–1920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Strijen MJ, de Monyé W, Schiereck J, Kieft GJ, Prins MH, Huisman MV. Single-detector helical computed tomography as the primary diagnostic test in suspected pulmonary embolism: a multicenter clinical management study of 510 patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):307–314. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Monyé W, Pattynama PM. Contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography of the pulmonary arteries: an overview. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27(1):33–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullins MD, Becker DM, Hagspiel KD, Philbrick JT. The role of spiral volumetric computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(3):293–298. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):227–232. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deonarine P, de Wet C, McGhee A. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography and pulmonary embolism: predictive value of a d-dimer assay. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:104–104. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall WB, Truitt SG, Scheunemann LP, Shah SA, Rivera P, Parker LA. The prevalence of clinically relevant incidental findings on chest computed tomographic angiograms ordered to diagnose pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1961–1965. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamare G, Schorr A, Chan C. Chest radiographs can minimize the use of computed tomography of the chest when combined with screening scores for pulmonary embolism evaluation. Chest. 2012;142(4_MeetingAbstracts):853A–853A. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perelas A, Dimou A, Saenz A, Rhee JH, Teerapuncharoen K, Rowden A. Incidental findings on computed tomography angiography in patients evaluated for pulmonary embolism. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(5):689–695. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-144OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sodhi KS, Gulati M, Aggarwal R, Kalra N, Mittal BR, Jindal SK. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography: utility in acute pulmonary embolism in providing additional information and making alternative clinical diagnosis. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;64(1):26–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.92484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Es J, Douma RA, Schreuder SM, Middeldorp S, Kamphuisen PW, Gerdes VE. Clinical impact of findings supporting an alternative diagnosis on CT pulmonary angiography in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2013;144(6):1893–1899. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Strijen MJ, Bloem JL, de Monyé W, Kieft GJ, Pattynama PM, van den Berg-Huijsmans A. Helical computed tomography and alternative diagnosis in patients with excluded pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(11):2449–2456. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schattner A. Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography to diagnose acute pulmonary embolism: the good, the bad, and the ugly: comment on "The prevalence of clinically relevant incidental findings on chest computed tomographic angiograms ordered to diagnose pulmonary embolism". Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1966–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozakin E, Kaya FB, Acar N, Cevik AA. An analysis of patients that underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography with the prediagnosis of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:470358–470358. doi: 10.1155/2014/470358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tresoldi S, Kim YH, Baker SP, Kandarpa K. MDCT of 220 consecutive patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: incidence of pulmonary embolism and of other acute or non-acute thoracic findings. Radiol Med. 2008;113(3):373–384. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terra-Filho M, Menna-Barreto SS, Comissão de Circulação Pulmonar da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia - SBPT Recommendations for the management of pulmonary thromboembolism, 2010 [Article in Portuguese] J Bras Pneumol. 2010;36(1):S1–68. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132010001300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2317–2327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein PD, Matta F, Sedrick JA, Saleh T, Badshah A, Denier JE. Ancillary findings on CT pulmonary angiograms and abnormalities on chest radiographs in patients in whom pulmonary embolism was excluded. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2012;18(2):201–205. doi: 10.1177/1076029611416640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack CV, Schreiber D, Goldhaber SZ, Slattery D, Fanikos J, O'Neil BJ. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: initial report of EMPEROR (Multicenter Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(6):700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conde MB, Melo FA, Marques AM, Cardoso NC, Pinheiro VG, Dalcin Pde T. III Brazilian Thoracic Association Guidelines on tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(10):1018–1048. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009001000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]