Abstract

Treatment strategies to address pathologies of fibrocartilaginous tissue are in part limited by an incomplete understanding of structure-function relationships in these load-bearing tissues. There is therefore a pressing need to develop microengineered tissue platforms that can recreate the highly inhomogeneous tissue microstructures that are known to influence mechanotransductive processes in normal and diseased tissue. Here, we report the quantification of proteoglycan-rich microdomains in developing, aging, and diseased fibrocartilaginous tissues, and the impact of these microdomains on endogenous cell responses to physiologic deformation within a native-tissue context. We also developed a method to generate heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs (hetTECs) with microscale non-fibrous proteoglycan-rich microdomains engineered into the fibrous structure, and show that these hetTECs match the microstructural, micromechanical, and mechanobiological benchmarks of native tissue. Our tissue engineered platform should facilitate the study of the mechanobiology of developing, homeostatic, degenerating, and regenerating fibrous tissues.

Injury and degeneration of fibrocartilaginous tissues, such as the knee meniscus and the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus, have significant consequences in terms of socioeconomic cost and quality of life.1,2 Despite the importance of these tissues in the activities of daily living, their structure-function relationships across multiple length-scales is poorly understood in developing, healthy, and diseased states. Absent this information, discovery and development of effective treatment strategies to address pathology has been hindered. Moreover, while there exist tissue-engineered platforms that can recapitulate various aspects of healthy native tissue structure and function,3–7 these do not generally address emergent tissue pathology or its consequences on tissue structure, mechanical properties, and biology. To that end, we set out to probe native tissue multi-scale structure-function relationships and to develop micro-engineered platforms to advance our understanding of tissue development, homeostasis, degeneration and regeneration in a more controlled manner.

Micro-engineered platforms that include pathological features would enable the precise control of the biochemical, structural, and mechanical properties of the cellular microenvironment. However, a limiting factor in designing such platforms is our incomplete understanding of the multi-scale structure-function relationships of native fibrocartilages. For example, mechanical strain transfer from the tissue to cellular level is highly non-uniform in these tissues,8–11 yet the mechanisms responsible for this inhomogeneity have not been identified. Indeed, while numerous biomechanical investigations have addressed tissue-level structure-function relationships using idealized schematic representations of highly ordered collagen structure,3,12–14 recent evidence suggests that the microstructure of many types of fibrocartilage is inhomogeneous. This inhomogeneity is characterized by aligned fibrous micro-domains (FmDs) containing fiber interruptions and junctions with non-fibrous proteoglycan-rich micro-domains (PGmDs) that are interspersed throughout the FmDs.8,9,15 While it is generally thought that such microstructural features regulate tissue-to-cell mechanical signal transfer, and thereby alter the in situ mechanobiologic response (i.e., early calcium signaling and eventual gene expression),8,9,15–17 this has not been experimentally evaluated. Given this emerging appreciation of the importance of multi-scale structure and its contribution to mechanics and biology in native fibrocartilage, it is imperative to further develop this area and inform the design of tunable micro-engineered platforms for studying context-dependent mechanotransduction of tissue physiology and pathology.

In the present work, we quantified the prevalence of PGmDs in developing and aging fibrocartilaginous tissues and evaluated how cells within distinct micro-domains of the tissue respond to physiologic deformation. In doing so, we demonstrated that the immediate intracellular calcium response to external mechanical perturbation in PGmDs and FmDs is distinct and context dependent. Next, we developed an approach to generate heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs (hetTECs) containing ‘engineered-in’ PGmDs within an otherwise FmD structure and demonstrated that these tissue analogues could match the microstructural, micromechanical, and mechanobiological benchmarks established by the native tissues. Collectively, these findings establish the emergent multi-scale structure of native fibrocartilage and its impact on micromechanics and mechanobiology, and provide a highly controlled micro-engineered platform in which to study the mechanobiology of developing, homeostatic, degenerating, and regenerating fibrocartilaginous tissues and to develop therapeutics to restore function.

Prevalence of PGmDs in the fibrocartilage microstructure

To quantify how the number and size of PGmDs change with development and aging, we examined Picrosirius Red and Alcian Blue stained outer meniscus tissue sections obtained from fetal (late trimester), juvenile (3–5 months), and adult (1–3 years) bovine animals, as well as menisci obtained from human donors (21–65 years) of varying body mass index (BMI: 12.4–64.4 kg/m2). PGmDs, defined by localized Alcian Blue stained inclusion >10,000 μm2, were present in the bovine tissues of all age groups (Fig. 1a–c) and in most of the human tissues (Fig. 1d). Second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging illustrated a near lack of organized collagen fibers within the PGmDs, with strong alignment and organization in the surrounding FmD regions (Fig. 1e). The number of PGmDs (per mm2) significantly increased from fetal to juvenile bovine groups, with no further change observed between juvenile and adult (Fig. 1f). The area of PGmDs progressively increased with development and aging in these bovine tissues, with the PGmD area in the adult menisci reaching levels that were significantly larger than all other groups (Fig. 1g). PGmDs in human tissue samples were similar in size and number compared to juvenile and adult bovine tissues (Fig. 1f and g), and positively correlated with donor age and BMI (p<0.05; Fig. 1h and i). Here, it is also important to note that tissues with a history of medically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis (OA) were associated with a higher BMI and had a significantly larger PGmD area (Fig. 1h and i, S. Fig. 1a). However, no differences were observed in the number of PGmDs between the No OA and OA group (S. Fig. 1b). The number of PGmDs also did not correlate with age or BMI (S. Fig. 1c and d).

Figure 1. Proteoglycan-rich micro-domains (PGmDs) become more prevalent and larger in dense connective tissues with development, aging, and mechanical adaptation.

Histology of (a) fetal, (b) juvenile, (c) adult bovine and (d) adult human meniscus specimens. Picrosirius Red staining indicates collagen and Alcian Blue staining indicates proteoglycans (PGs). Scale bars = 250 μm. (e) Polarized light and second harmonic generation (SHG) images of a human outer meniscus section (Alcian Blue) showing large PGmD regions lacking organized collagen. Scale bar = 250 μm. (f) Quantification of the number of PGmDs per mm2 and (g) PGmD area in individual native tissue specimens as a function of age/species. Data are presented as median ± interquartile range. Kruskal Wallis (p<0.05) with Bonferroni-Dunn’s post-hoc. p*: Bonferroni adjusted p value. (h) Correlation between median PGmD area and age in human tissue. (i) Correlation between median PGmD area and body mass index (BMI) in human tissue. Shades of gray indicate whether the specimen came from a donor that was underweight (lightest shade), of normal weight, overweight, or obese (darkest shade). Spearman’s rank correlation. Solid line: regression line; Dashed line: standard error of regression; ρs: Spearman’s rho. Blue dots indicate tissues with a diagnosed history of osteoarthritis (OA).

These results demonstrate that proteoglycans exist in discrete and localized domains within the outer meniscus, and emerge during the fetal to post-natal developmental transition. With aging, the size of individual PGmDs increases in both bovine and human menisci, while their total number remains unchanged. In human tissues, pathologic factors, such as BMI and OA, also appear to play a role in modulating the PGmD size. While it is outside the scope of this study to determine whether the emergence of PGmDs represents a normal part of aging or a pathologic state in fibrocartilages, we postulate that an optimal PGmD number and size may exist to support mechanical compression in the normal fibrocartilages, and that these inclusions further accumulate and grow in size with the onset of pathology. Indeed, PGmDs are present in the healthy fibrocartilage-rich, wrap-around tendons (that support both tensile and compressive loading), but when these tissues are translocated to bear only tension in vivo, PGmD area decreases significantly18. Furthermore, PGmDs accumulate to an excessive degree in tendinopathic tissue and compromise tendon mechanical function.19–23 This suggests that PGmDs may form as a consequence of development and mechanical adaptation in normal tissues, but also can undergo maladaptive remodeling and further accumulate and grow in size with the onset of pathology.

Strain transfer in native fibrocartilage micromechanics

Regardless of whether these emergent micro-domains represent a homeostatic or diseased state, they most certainly create abrupt changes in structure which influence macro-to-micro scale strain transfer in the tissue. To investigate this, we performed uniaxial tensile tests on fresh fetal, juvenile, and adult bovine outer meniscus specimens using a custom confocal mounted microtensile device8,16,24 that enabled simultaneous tracking of endogenous cells (Fig. 2a and b). The presence of PGmDs within analyzed regions was confirmed after testing via histological indexing to the region of interest (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. PGmDs attenuate local strain transmission and cell deformation in fibrocartilage.

(a) Schema of mechanical test. Tissue samples were stretched uniaxially while simultaneously monitoring position and size of cells and nuclei in situ via confocal microscopy. (b) Lagrangian strain at the tissue and local ECM length scale was computed by tracking centroids of surface markers and cell nuclei, respectively. Cell strain was calculated by measuring the change in the long axis of individual cells. (c) Histology (Alcian Blue and Picrosirius Red) showing the presence of PGmDs within an imaged region and a micrograph of cell nuclei in both PGmD and FmD. Scale bar = 250 μm. Strain transfer from the tissue to ECM (FmD and PGmD) in bovine (d) fetal, (e) juvenile, (f) adult, and (g) non-OA human outer meniscus; PGmD regions showed attenuated strain transfer. ★: p<0.05 vs FmD via extra-sum-of-squares F-test; m: slope of linear regression (average strain transfer ratio). Dashed line represents 1:1 relationship. n=10–20 triads for each FmD and PGmD. (h) Finite element simulated longitudinal strain map of untreated and ChABC treated specimens at 10% applied strain. Arrow indicates PGmD. (i) PGmD/FmD strain ratio from experimental data and finite element (FE) simulations of untreated and ChABC treated specimens. (j) Digestion of proteoglycans (via ChABC treatment) from PGmDs resulted in a partial recovery of strain transfer in juvenile meniscus specimens. ★: p<0.05 vs FmD and #: p<0.05 vs PGmD via extra-sum-of-squares F-test. n= 21 triads for ChABC treated. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Strain analysis showed that while the strain fields within the extracellular matrix (ECM) were heterogeneous (S. Fig. 2a–d), average strain transfer from the tissue to ECM-level was linearly correlated in all age groups (Fig. 2d–g, S. Fig. 2e). In fetal tissues, where smaller PGmDs were present (Fig. 1g), tissue-level strain transfer to both the FmD and PGmD was similar, with an average strain transfer ratio of ~80% (Fig. 2d). However, strain transfer from the tissue to ECM-level was more heterogeneous in juvenile and adult tissues. Consistent with Upton et al.,9 local strains measured in the FmDs of these tissues were occasionally amplified or more often attenuated, and depended on the underlying fibrous structure (e.g., fiber discontinuity and interruptions; S. Fig. 2d). On average, the local matrix strain was attenuated from the tissue-level strain, where approximately 65% of tissue strain was transferred to the ECM level in FmDs in these age groups (Fig. 2e and f, S. Fig. 2e). On the contrary, the average strain transfer to the PGmDs was significantly attenuated compared to the FmDs. That is, in PGmDs, only ~20–25% of tissue-level strain was transferred to the ECM level (Fig. 2e and f, S. Fig. 2e). A similar trend, with greater strain attenuation in PGmDs compared to FmDs, was also observed in human tissues (3 donors tested mechanically; age range 40–50; Fig. 2g).

Highly aligned tissues and materials generally have a large Poisson’s ratio, which leads to transverse compression when they are stretched in the fiber direction. In the FmDs, this transverse compression would act to accentuate strain transfer. Conversely, in the PGmDs, we hypothesized that the local composition, mechanical properties, and connectivity of the PGmDs to the surrounding FmD would attenuate deformation. To test this hypothesis, we developed a computational finite element model of these micro-domains based on high resolution imaging of the fibrous interface between FmDs and PGmDs. The imaging, both polarized light and second harmonic generation (SHG), showed that collagen fiber density and organization was lower in the PGmDs compared to the FmDs (Fig. 1e). Collagen fibers from the FmDs did not appear to directly engage the PGmDs, instead wrapping around them. When the PGmD was assigned values matching that of native articular cartilage,25,26 the lack of strain transfer into the PGmD was recapitulated in the model, matching our experimental results (Fig. 2h and i).

In addition to a lack of fibrous connectivity, the high PG content of the PGmD should impart a significant amount of swelling pressure and local charge repulsive forces which would resist the inherent transverse compression due to the Poisson effect. To determine how this might contribute to the attenuated strain transfer in PGmDs, we digested juvenile meniscus tissues with chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) and performed uniaxial tension testing. Treatment with ChABC substantially reduced (by ~70%) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content in the tissue (S. Fig. 3a). Histologically, digested PGmDs showed a marked reduction in Alcian Blue staining intensity (S. Fig. 3b). As a consequence of reduction of these charged proteoglycans, strain transfer to the digested PGmDs was partially restored, reaching ~50% of tissue-level strain transfer (Fig. 2j). Buffer treatment (control) had no effect on strain transfer to the FmDs and PGmDs (S. Fig. 3c and d). The finite element model of the PGmD embedded in a fibrous tissue domain validated this finding. When the PGs were ‘removed’ from the finite element model, mirroring treatment with ChABC,27 the strain transmission was restored (Fig. 2h and i). Together, these experimental and computational findings show that the charged GAG chains of the PGs are key constituents of the PGmDs and that their combined swelling pressure and repulsive characteristics contribute substantially to the lack of strain transfer to PGmDs in native tissue (S. Fig. 2e).

The above results suggest that the presence of PGmDs attenuate the mechanical inputs that reach the cellular microenvironment, where cell response to mechanical perturbation occurs. Indeed, at the cell and nuclear level, strain in the cells residing in the PGmDs were progressively more attenuated with age. Overall, 90–100% of ECM strain was transferred to cells in fetal tissues, while 60–70% of ECM strain was transferred to cells in juvenile and adult tissues (S. Fig. 4a–h).

Given the progressive attenuation of strain transfer across multiple length scales (i.e., tissue to ECM, ECM to cells, and cells to nuclei), cells in both FmDs and PGmDs experience diminished magnitudes of tissue-level strain, with more attenuation occurring in aged samples. These results also indicate that cells within the PGmDs reside within a much more ‘strain-shielded’ microenvironment relative to the cells within FmDs. These PGmDs thus establish a localized cellular microenvironment in which tissue-level tensile strain is significantly attenuated, likely impacting the mechanobiologic response. Furthermore, aberrant growth of PGmDs with progression of pathology may further impact normal mechanobiology by subjecting a greater number of cells within the tissue to abnormal (decreased) mechanical stimulation.

Calcium signaling in native fibrocartilage mechanobiology

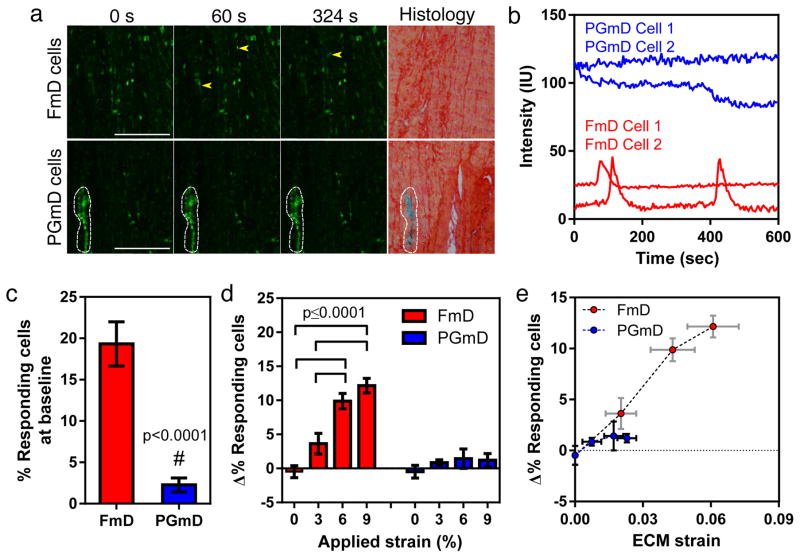

To assess the effect of tissue microscale heterogeneity on mechanobiology, we next examined how strain at the ECM-level regulates intracellular calcium signaling in cells within FmDs and PGmDs in response to tissue-level tensile strain. Cells within PGmDs had an elevated baseline signal intensity compared to those within FmDs (Fig. 3a and b). Furthermore, the PGmD resident cells had a lower frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations (<5%) compared to FmDs (~20%) prior to strain and were much less responsive to applied strain compared to cells in FmDs (Fig. 3c and d, S. Fig. 5). Application of tissue level strain (6%) increased the peak amplitude of calcium transients in FmD cells, but did not change the duration or frequency of their oscillations, consistent with our previous findings16 (S. Fig. 6a–d). Moreover, the percentage of FmD cells showing calcium oscillations progressively increased in response to the level of applied strain, with significantly more cells responding at 6% and 9% strain compared to 0 and 3% (Fig. 3d). In contrast, application of tissue level strain had no effect on cells in the PGmDs in terms of the percentage of cells responding (Fig. 3d). This is likely due to the strain shielding that occurs within the PGmDs, where the ECM strain was less than 3% when 9% strain was applied to the tissue (Fig. 2e, Fig. 3e). Indeed, the change in percent responding cells was less than 5% from baseline for both FmD and PGmD cells when the local matrix strain was under 3% (Fig. 3e). These results suggest that attenuation of externally applied strain within PGmDs has a profound effect on the calcium responsivity of cells located within these micro-domains.

Figure 3. PGmDs alter local cell mechano-response to applied tissue level mechanical deformation.

(a) Representative time series confocal snapshots at 0, 60, and 324 sec, and corresponding histology (Alcian Blue and Picrosirius Red) for a juvenile meniscus tissue. Cells in FmDs respond to 3% strain with an increase in the number of calcium oscillations over time, as indicated by the yellow arrowheads. Conversely, cells in PGmDs do not respond to stretch, but have an elevated baseline calcium signal. White outline indicates PGmD area. Scale bar = 250 μm. (b) Representative fluorescence intensity traces for cells in FmDs and PGmDs after stretch. (c) Percentage of responding cells at baseline in the FmD and PGmD regions. #: p<0.0001 vs FmD via Student’s t-test (two-tailed and unpaired). n=21 and 23 for FmD and PGmD, respectively. (d) Change in the percentage of responding cells with applied stretch relative to baseline levels. n=5–7 per strain group. One-way ANOVA (p<0.05) with Tukey’s post-hoc. (e) Percent responding cells (from Figure 3d) plotted against measured ECM strain, showing relative strain dependence. All data in (a)-(e) are presented for juvenile meniscus. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Fabrication of heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs

The above findings indicate that fibrous tissues contain micro-domains whose composition, mechanical properties, and mechanosensitivity differ from the bulk ECM of these fibrous tissues. While it is not clear whether these micro-domains represent a homeostatic response to mechanical demands or a pathologic consequence of aging and/or disease, they certainly play a major role in tissue physiology. To address this in a more tractable format, we developed heterogeneous tissue-engineered constructs (hetTECs) to mimic the microstructural, micromechanical, and mechanobiological factors observed in native fibrocartilage. To fabricate hetTECs, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) micro-pellets and meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFCs) were seeded onto aligned electrospun nanofibrous poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) scaffolds7,28 (Fig. 4a). On day 3, an additional sheet of scaffold was layered on top of the construct (Fig. 4a), and constructs were maintained in a chemically defined media containing TGF-β3 for up to 8 weeks. Visualization of the cells on day 3 confirmed that MSC micro-pellets (red/orange) were well-dispersed within the proliferating MFCs (green) attached to the scaffold (Fig. 4b). Histological analyses after 1 week revealed that MSC micro-pellets deposited proteoglycans, forming PGmDs, while MFCs deposited collagen in the vicinity of the PGmD (Fig. 4c). By 4 weeks, MFCs had continued to lay down a collagen-rich matrix (Fig. 4c). By 8 weeks, the size of PGmDs significantly increased, to the level of the juvenile meniscus, and these domains had become more fully enmeshed within the surrounding collagenous matrix (Fig. 4c and d). HetTECs containing only FmD and both FmDs and PGmDs accumulated increasing proteoglycan content with time (S. Fig. 7a). Similar trends were observed for total collagen content (S. Fig. 7b), with constructs containing PGmDs alone producing the least amount of collagen. Immunostaining showed that type II collagen was strongly localized within the PGmDs by week 8 (Fig. 4e), while type I collagen was uniformly dispersed within the surrounding FmD (Fig. 4f). Occasionally, PGmDs showed cellular outgrowths rich in type II collagen (red arrow on Fig. 4e) that connected neighboring PGmDs over time (S. Fig. 8). Despite the density of type II collagen within the engineered PGmDs, this collagenous architecture was less dense and less ordered than was observed in the surrounding FmDs at week 4 and 8 (S. Fig. 9), similar to that observed in native tissue (Fig. 1e). These differences in collagen type and structure had profound effects on the cell nuclear morphology, with nuclei in FmDs being highly aligned and elongated in the fiber direction, while the nuclei of cells in PGmDs were smaller, rounder, and randomly oriented (S. Fig. 10a–c).

Figure 4. Heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs (hetTECs) reproduce the structural, compositional, and molecular features of native tissue FmDs and PGmDs.

(a) Schematic of the creation of a hetTEC containing FmDs with ‘engineered-in’ PGmDs. Isolated meniscus fibrochondrocytes (MFCs) and chondrogenically differentiated mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) micro-pellets were co-seeded between two layers of aligned nanofibrous scaffold. (b) MSC micro-pellets visualized by CellTracker™ Red and MFCs by CellTracker™ Green 3 days after construct assembly. Scale bar = 200 μm. (c) Histology (Alcian Blue for PGmD and Picrosirius Red for FmD) of hetTEC after 1, 4, and 8 weeks of culture. Engineered PGmDs increase in size with culture duration. Collagen deposited by MFCs in the engineered FmD follows the underlying nanofiber direction (arrow). Scale bar = 100 μm. (d) PGmD area as a function of culture duration. Values indicate mean area at each time point. One-way ANOVA (p<0.05) with Bonferroni’s post-hoc. p*: Bonferroni adjusted p value. n=10–11 per group. Data presented as mean ± s.d. (e) Type II collagen immunostaining of hetTEC at week 8. Arrow points to engineered PGmD. Scale bar = 100 μm. (f) Type I collagen immunostaining of FmD region of hetTEC at week 8. Arrow indicates scaffold fiber direction. Scale bar = 100 μm. (g) Single cell quantitative RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA FISH) of hetTECs. Representative images showing fluorescent spots (indicated by red arrow) corresponding to individual aggrecan (AGG) mRNA in cells in either an FmD or a PGmD at week 4. Scale bar = 5 μm. (h) AGG expression (normalized to GAPDH) as measured by single cell quantitative RNA FISH. n = 152 and 250 cells for FmD and PGmD, respectively. Mann-Whitney U test (two-tailed and unpaired). Data presented as median ± interquartile range. (i) Young’s modulus (MPa) of hetTEC as a function of cellular constituents. PGmD inclusion did not change bulk tensile mechanics compared to scaffold alone. Seeding of MFCs to produce the FmD significantly increased the Young’s modulus. Dashed line represents modulus of scaffold prior to seeding (10.0 ± 0.6 MPa). +: p<0.05 vs PCL scaffold only. One-way ANOVA (p<0.05) with Bonferroni’s post-hoc. n=3 each. Data presented as mean ± s.d.

To determine the molecular identity of cells located in the FmD and PGmD, quantitative RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to identify individual aggrecan (AGG) and GAPDH mRNA at the single cell-level.29,30 The AGG/GAPDH mRNA ratio was significantly greater in the cells in the PGmDs compared to cells in the FmDs (Fig. 4g and h). Here, it is important to note that while PGmDs exhibit increased AGG/GAPDH ratio, the overall proteoglycan content does not increase over time (S. Fig 7) because the engineered PGmDs only constitute a small fraction of the entire hetTECs.

Bulk construct mechanics were measured in tension at week 8. HetTECs with PGmDs alone did not alter the construct Young’s modulus in comparison to unseeded PCL scaffolds (Fig. 4i). Conversely, seeding of MFCs to produce the FmD significantly increased the Young’s modulus (Fig. 4i), suggesting that the type I collagen-rich matrix deposited by MFCs is essential for establishing the macro-scale tensile function of the hetTECs. The tensile modulus of hetTECs containing only FmD was similar to those including both FmDs and PGmDs, suggesting that the PGmDs did not compromise the bulk tissue function, consistent with native tissue.

HetTEC micromechanics and mechanobiology

To determine how tissue to ECM-level strain transfer in hetTECs is compared with the native tissue, we performed uniaxial tension testing on hetTECs while simultaneously tracking DAPI-stained nuclei. With strain, hetTECs containing PGmDs showed highly heterogeneous strain fields, where the strain magnitude within the PGmD was considerably lower than that of the surrounding FmD (Fig. 5a). Consistent with our measures of native tissue, quantification of strain transfer in the FmD was direct (80–90% strain transfer ratio), while in the engineered PGmDs strain transfer was significantly attenuated (0–15% strain transfer ratio) at both 4 and 8 weeks (Fig. 5b, S. Fig. 11). Similar trends were observed in hetTECs containing only PGmD or FmD regions (Fig. 5b, S. Fig. 11). These results demonstrate that hetTECs with engineered-in PGmDs recapitulate the heterogeneous strain transfer to the micro-scale level that was observed in both human and bovine juvenile and adult tissues.

Figure 5. HetTECs reproduce native tissue domain-dependent strain transfer characteristics and mechano-response.

(a) Color maps of local ECM strain (Exx; loading and fiber direction) for hetTECs matured for 8 weeks with application of 0, 3, 9 and 15% strain. Red box indicates location of a PGmD within the hetTEC. (b) Quantification of local ECM strain within FmD and PGmD regions of hetTEC at week 8. PGmD only: construct containing only PGmD/MSC-micro-pellets; FmD only: construct containing only FmD/seeded MFCs; PGmD/FmD: construct containing both PGmD and FmD components. #: p<0.0001 vs FmD via extra-sum-of-squares F-test; ##: p<0.0001 vs PGmD/FmD (FmD) via extra-sum-of-squares F-test; m: slope of linear regression (average strain transfer ratio). Dashed line represents 1:1 relationship. n=35~50 triads per group. (c) Representative calcium response for hetTEC cells in FmDs and PGmDs over 600 sec before or after the application of 6% strain. As in native tissue, cells in PGmDs do not respond to strain and have a higher baseline calcium level. (d) Percent increase in responding cells in hetTEC FmD and PGmD regions with application of 6% strain. #: p=0.04 vs FmD via Student’s t-test (two-tailed and unpaired). n=3 per group. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

To further probe the recapitulation of native tissue functionality in engineered hetTECs, we next monitored intracellular calcium signaling in response to applied strain. At 0% strain, cells within FmDs showed spontaneous calcium oscillations and cells within the PGmDs showed elevated baseline intensity (Fig. 5c, S. Fig. 12a and b). Application of 6% strain caused a greater number of FmD cells to respond compared to cells within PGmDs, which were largely unresponsive to applied strain (Fig. 5c and d). Furthermore, the relative baseline calcium signaling intensities measured in hetTECs also mimicked the calcium signaling intensities measured in native tissues, where cells within PGmD exhibited higher baseline intensities than the cells within FmDs (Fig. 3b and 5c). These findings demonstrate that the mechanobiologic response (intracellular calcium signaling) of cells in hetTECs mirrors (and is perhaps even more sensitive S. Fig. 12c–f) than that seen in cells within the juvenile native meniscus micro-domains.

Outlook

While this work quantified the prevalence of PGmDs in fibrocartilage during maturation and aging and established their micromechanical and mechanobiologic roles in native tissue, one central question that remains unanswered is whether the PGmDs are beneficial or detrimental to tissue health and function. During development of fibrocartilaginous tissues, PGmDs do play an important and beneficial role. Indeed, there may be an optimal number and size of PGmDs in healthy tissue, but PGmDs may also accumulate to a pathologic degree with disease progression or in response to injury. For instance, PGmDs are present in healthy wrap-around tendons18 (where they help the tissue resist lateral compression) but also over-accumulate in the tendinopathic tissues19,23,31 (where they compromise tensile load-bearing capacity). Interestingly, within injured tendons, tendon-derived progenitor cells participate in regeneration of the FmD regions, but can also aberrantly undergo chondrogenesis,32 resulting in a pathologic level of PGmDs in the repairing tissue. This may suggest that the presence and accumulation of PGmDs during aging could be a consequence of aberrant differentiation of endogenous stem and progenitor cells, perhaps as a result of microscale damage and altered local microenvironments within the otherwise ordered FmDs. Answering such questions may ultimately aid in the development of effective therapeutic strategies to modulate and maintain the optimal level of the PGmDs in aging fibrocartilaginous tissues and restore such optimal levels in disease or following injury.

Answering such questions in native tissues is difficult, however, given their complexity and the scarcity of tissues with controllable levels of pathology. To develop a more tractable and defined framework in which to study the impact of PGmDs, we engineered hetTECs inclusive of PGmDs, producing constructs that matched the microstructural, micromechanical, and mechanobiologic benchmarks of native tissue (Fig. 6). These hetTECs may serve as an in vitro platform in which to study the mechanobiology of developing and pathologic tissues in a more controllable fashion, and to develop therapeutic strategies to halt or reverse the progression of tissue degeneration. For example, hetTECs could be used to identify the PGmD area fraction in tissue at which tissue-level mechanical properties are compromised. Additionally, by probing the time course over which PGmDs grow in conditions of physiologic and altered loading (e.g., partial transection, mechanical overload, fatigue), hetTECs may be used to determine whether the PGmDs develop as a consequence of mechanical adaptation or pathologic consequences of aging, degeneration, and/or injury.

Figure 6. Heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs (hetTECs) match the (a) microstructural, (b) micromechanical, and (c) mechano-biological benchmarks established by heterogeneous native fibrocartilages.

Box in (a) indicates range of PGmD area in native tissues. Data presented as mean ± s.d. Red and blue shaded areas in (b) indicate 99% confidence interval of linear regression of FmD and PGmD ECM native tissue strain. Red and blue dots show response in hetTEC micro-domains after 8 weeks of culture. Data presented as mean ± s.e.m. Blue and red traces in (c) show calcium signaling in PGmD and FmD regions of native and engineered hetTECs in response to applied strain. All native tissue shown are from juvenile bovine meniscus.

While the current study focused solely on fibrocartilages, tissue microstructure and its influence on micromechanics and mechanobiology and the hetTEC construction algorithms that create micro-engineered heterogeneous features can be extended to other types of dense tissues that contain structural micro-domains or develop them in response to damage or disease. Muscle, cardiovascular tissue, skin, and neural tissue will benefit from these native tissue and hetTEC approaches applied to homeostasis and pathology. Together, these findings demonstrate the impact of emergent heterogeneous micro-scale tissue features on normal tissue function, and validate a method to micro-engineer heterogeneous tissue constructs containing these complex features to address and correct tissue pathology.

Methods

Preparation of aligned nanofibrous scaffolds

Aligned nanofibrous materials, poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL, mol. wt. 80 kDa, Shenzhen Bright China Industrial Co., Ltd., China) materials were formed by electrospinning.33 PCL was dissolved at 14.3% wt/vol in a 1:1 mixture of tetrahydrofuran and N,N-dimethylformamide (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), loaded into a syringe, and extruded at 2.5 ml/hour through an 18G stainless steel spinneret charged to create a voltage gradient of +1 kV/cm over an air gap of 13 cm. Electrospinning jets were collected onto a cylindrical mandrel rotating at a surface velocity of 10m/sec to direct alignment of collected fibers. PCL scaffolds (10 × 65 × 0.3 mm3) were hydrated and sterilized in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100, 70, 50, 30%; 30 mins/step). To enhance cell attachment, scaffolds were incubated in a solution of human fibronectin (20 μg/ml in PBS, F4759, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 12 hours prior to cell seeding.

Isolation and preparation of cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were isolated from juvenile bovine tibiofemoral joints (3–6 months, Research 87, Inc., Boylston, MA)34 and expanded through passage two. MSCs were labeled with Cell Tracker Red (CellTracker™ Red CMTPX, C34552, Molecular Probes®, Grand Island, NY) to enable visualization with extended culture and were formed into micro-pellets (5,000 cells/pellet) by centrifugation at 300×g for 5 min. Micro-pellets were cultured for one week in a chemically defined serum-free chondogenic medium (high glucose DMEM with 1× penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μg ml−1 ascorbate 2-phosphate, 40 μg ml−1 l-proline, 100 μg ml−1 sodium pyruvate, 6.25 μg ml−1 insulin, 6.25 μg ml−1 transferrin, 6.25 ng ml−1 selenous acid, 1.25 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin and 5.35 μg ml−1 linoleic acid) with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 to induce chondrogenesis (including production of proteoglycans).34

Meniscal fibrochondrocytes (MFCs) were isolated from juvenile bovine outer menisci (3–6 months, Research 87, Inc., Boylston, MA).35 Menisci were sectioned into 1mm3 cubes and MFCs were allowed to migrate out of the tissue over 1–2 weeks, after which they were expanded through passage 2 in a basal medium consisting of high-glucose (hg) DMEM containing penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (PSF) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MSCs and MFCs were isolated from same donors. MFCs were labeled with Cell Tracker Green (CellTracker™ Green CMFDA, C7025, Molecular Probes®, Grand Island, NY) prior to seeding onto scaffolds.

Fabrication of heterogeneous tissue engineered constructs

To form engineered tissues inclusive of both fibrous micro-domains (FmDs) and PG-rich micro-domains (PGmDs), 100 MSC micro-pellets were mixed with 1 million MFCs and seeded onto a single scaffold surface. Constructs containing MSC micro-pellets alone (PGmD only) or MFCs alone (FmD only) were also created by seeding either 100 MSC pellets or 1 million MFCs, respectively. Constructs were cultured in chemically defined media with TGF-β3, with care taken to not disturb the construct over the first three days. At this time point, to visualize micro-pellets and MFCs, a set of hetTECs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 37°C, and imaged using an epi-fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U, Melville, NY). For constructs intended for long-term culture, fresh scaffolds were layered on top of the original seeded scaffold, creating an internal space for organized tissue development. This entire construct was cultured in chemically defined media with TGF-β3 for up to 8 weeks.

Preparation of native tissues for PGmD quantification

Bovine menisci were obtained from fetal (late trimester; n=12; Animal Technologies, Tyler, TX), juvenile (3–6 months; n=11; Green Village Packing Co., Green Village, NJ), and adult (3–5 years; n=16; Green Village Packing Co., Green Village, NJ) knee joints within 12-hours of sacrifice. Human menisci (n=11; donor ages 21–65 years) were procured from a commercial and IRB-approved source (National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI), Philadelphia, PA). Body mass index (BMI) for human donors was calculated based on height and weight information provided by the vendor. The vendor provided medical history on each donor and indicated whether the donors had been previously diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis (OA). Rectangular tissue samples were dissected from the outer central (body) region of each meniscus using a scalpel, in the axial plane. Dissected samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 1 week at room temperature. Fixed samples were then paraffin-processed and sectioned (4 μm thickness) using a paraffin microtome in the direction parallel to predominant collagen fiber direction (i.e., in the axial plane of the meniscus).

Sectioned samples were rehydrated and stained with Alcian blue and Picrosirius red to identify proteoglycans (PG) and collagens, respectively. Stained samples were subsequently imaged using a light microscope equipped with a DSLR camera. For quantitative analyses, no more than 2 sections from each bovine meniscus were used (n=24, 23, 32 slides for bovine fetal, juvenile, and adult tissues, respectively). For the human menisci, 5–13 sections from each donor were used (n=89 slides in total). PGmD area and number (per mm2) were quantified using a custom MATLAB program (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The program extracted the blue channel from the histological image, converted the image to binary, and segmented the boundaries of identified objects (i.e., Alcian blue stained regions). During the analysis, any identified region with an area less than 10,000 μm2 was discarded to eliminate noise resulting from diffuse Alcian blue staining.

Histological analysis of hetTECs

For histological analysis, constructs (at week 1, 4 and 8) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 37°C, and embedded in Cryoprep frozen section embedding medium (Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Constructs were sectioned (8 μm thickness) with a cryostat microtome (Microm HM-500M Cryostat, Ramsey, MN) in the fiber plane (fiber direction) of the sample. Sections were stained with Alcian Blue and Picrosirius Red to visualize proteoglycans and collagens, respectively. PGmD area was measured using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). For immuno-histochemical detection of type I and II collagen, samples were incubated in proteinase K (S3020, Dako, CA) for 4 min, followed by blocking with 10% normal goat serum (#50062Z, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibody (Type I collagen: MAB3391, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA; Type II collagen: 11–116B3, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, IA) was applied at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 overnight at 4°C, followed by washing and incubation with secondary antibody (DAB150 IHC Select; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Signal was visualized using DAB chromagen reagent (DAB150 IHC Select; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Stained sections were visualized and imaged using a bright field microscope (Nikon Eclipse TS 100, Melville, NY).

Quantitative RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis

For RNA FISH analysis, hetTECs were embedded in Cryoprep frozen section embedding medium (Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), frozen at −80°C, and cut into 6 μm thick sections in the plane of the forming tissue. Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight. RNA-FISH then was performed as previously described.29,30 Briefly, sections were stained with cy3-aggrecan probes, Atto647N-GAPDH probes, and DAPI. Aggrecan expression was assessed as this is the core protein of the major type of proteoglycan present in load-bearing fibrocartilage tissues (i.e., meniscus and annulus fibrosus) that contribute to tissue compressive function. Furthermore, localized aggrecan accumulation (chondroid deposits) is a hallmark of tendon pathology.20,23,31 Full oligonucleotide probe sequences are provided in Supp. Table 1 (full oligonucleotide probe sequences for single cell RNA FISH). Samples were imaged using a Leica DMI600B microscope equipped with a 100× objective and appropriate filter sets, in 0.7-um optical z-sections through the section depth. For analysis, cells were manually segmented with those in FmDs and PGmDs distinguished from one another based on transmitted light images and nuclear morphology.8 For each cell, individual RNA molecules (visualized as diffraction limited spots) were identified and counted using custom MATLAB software.29,30

Second harmonic generation imaging

To visualize collagen structure and organization within FmD and PGmD regions of native and engineered tissue, second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging was carried out on 4 μm thick human outer meniscus paraffin sections stained with Alcian blue and 8 μm thick cryo-sectioned hetTECs sections taken at week 4 and week 8. SHG imaging was performed at an excitation wavelength of 840 nm (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany).36 For native tissues, polarized light images of the matching locations were also acquired.

Biochemical composition of native tissues and hetTECs

Fresh (untreated), chondroitinase ABC (ChABC)-treated (1U/ml; 4 hours on a shaker at 37°C), and ChABC Tris Buffer (50mM Tris and 60mM Sodium Acetate; 4 hours on a shaker at 37°C) treated bovine juvenile meniscus samples were dehydrated in an oven at 60°C overnight and dry weight was measured (n=8 for each untreated and ChABC groups, n=6 for ChABC Tris Buffer group). hetTECs (n = 3 for PGmD only, FmD only, and PGmD/FmD groups) were weighed and digested in proteinase K (03115828001, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at 60°C overnight. Digestate from hetTECs was hydrolyzed overnight in 6 M HCl at 110 °C. Total glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content was determined using the 1,9-dimethylmethlene blue (DMMB) assay.37 GAG contents of native tissues and hetTECs were normalized to the sample dry and wet weights, respectively. Collagen content of hetTECs was determined using the orthohydroxyproline (OHP) assay, assuming a ratio of OHP to collagen of 1:7.14.37 Collagen content of hetTECs was normalized by the sample wet weight.

Mechanical evaluation of hetTECs

The Young’s modulus of intact hetTECs was evaluated at 8 weeks via uniaxial tensile testing (n = 3 for PGmD only, FmD only, and PGmD/FmD groups) using an Instron 5848 electromechanical testing system equipped with a 100N load cell (Instron, Canton, MA). Cross-sectional area of each scaffold was measured using a custom non-contacting laser-based system.38 Gauge length of the sample was determined using a digital caliper. Samples were pre-conditioned with 10 cycles of sinusoidal loading to 0.1 N at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. Samples were then ramped to failure at a strain rate of 0.1%/sec. Tensile modulus was calculated by performing linear regression to the linear region of the stress-strain plot.

Sample preparation for micro-mechanical testing

Bovine meniscus tissues were obtained from fetal (n=10), juvenile (n=9), and adult (n=8) knee joints within 12-hours of sacrifice. Isolated meniscus tissues were maintained in culture medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, DMEM; Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for no longer than 3 hours. Immediately prior to fluorescent staining and mechanical testing, test specimens were trimmed to 12.0 × 3.0 × 0.3–0.8 mm (length × width × thickness) using a scalpel.

Human meniscus tissues (age 45–50; n=3; previously frozen; remaining tissues from the PGmD quantification study above) were obtained from NDRI (as above) and prepared in a similar manner. Double-layered hetTECs (at week 4 and 8) were sectioned from the top surface of the construct using a freezing stage sledge microtome (Leica SM2400, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) until the FmDs and PGmDs were exposed (i.e., removing the overlaying scaffold to expose the central region of the construct).

To probe the influence of proteoglycans within native tissue, additional bovine juvenile meniscus tissues were dissected, trimmed, and treated with 1U/mL chondroitinase ABC (ChABC; n=5; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or with ChABC Tris buffer (n=4; 50mM Tris and 60mM Sodium Acetate) for 4 hours on a shaker at 37°C prior to florescent staining and mechanical testing.

Prior to micro-mechanical testing, cells and nuclei in native tissue samples were stained with 0.01 μg/mL FM4–64® (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and NucBlue™ Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in 1X PBS, respectively. For human tissues and ChABC and ChABC Tris Buffer treated samples, cell nuclei were stained using 10 μM DRAQ-5® (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 30 min. Samples were washed in 1X PBS to remove excess dye. Subsequently, tissue markers were applied to the surface of each native tissue sample using a Sharpie® permanent marker. Cell nuclei within hetTECs were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, ProLong ® Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI, P36935, Molecular Probes®,Grand Island, NY ) prior to micro-mechanical testing.

Micro-mechanical testing to quantify strain transfer

To investigate how the tissue-level mechanical strain was transferred to the FmD and PGmD regions, and subsequently to the cells and nuclei within each of these regions in the native tissue, uniaxial tensile testing was performed using a custom micro-mechanical test device mounted on top of an inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 5 LIVE; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).8 Samples were placed in grips with tissue markers facing up and a 30 mN preload was applied to remove tissue slack. Incremental grip strains of 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15% were applied at a strain rate of 0.1%/sec. Multi-channel z-stack confocal images were acquired at 0% strain and 30 sec after each strain increment using a water-immersion 25X lens (FOV: 360 × 360 μm2; Hoechst: 405 nm/BP 420–480 nm; FM4–64: 515 nm/LP 650 nm; DRAQ-5: 633 nm/LP 650 nm). The same group of cells and nuclei was tracked with each level of applied strain. The position of tissue surface markers was captured using a CCD camera concurrently with confocal imaging. All testing was performed in a DMEM bath at room temperature.

During confocal imaging, PGmDs were preliminarily identified using previously determined characteristics of nuclear shape within PGmDs.8 That is, nuclei within PGmDs were rounder, with a nuclear aspect ratio ≤2.15, while nuclei of cells located within FmDs were elongated with nuclear aspect ratio > 2.15.8 Given that the average fetal NAR (1.95±0.64) was smaller than average NAR in juvenile and adult tissues (2.31±1.05), an NAR cut-off of 1.7 was used for fetal specimens to bin cells as being in an FmD or PGmD. Subsequent to mechanical testing, the presence of actual PGmDs within the imaged regions was confirmed via histology (staining of PGmD with Alcian Blue). At both 4 and 8 weeks, hetTECs were tested in a similar manner using a custom device mounted on an inverted epi-fluorescent microscope (Nikon T30, N Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY).39 For these samples, 0 to 15% grip-to-grip strain was applied in 3% increments.39 At each strain increment, images of cell nuclei were acquired using a CCD camera and local strain calculated as described below.

Multi-scale strain calculation

Two-dimensional (2D) tissue strains were calculated from the centroids of the surface tissue markers. Similarly, two-dimensional (2D) extracellular matrix (ECM) Lagrangian strains were calculated from the position of the centroid of nuclear triads at each strain level (n=20, 10 triads for FmD and PGmD of fetal; n=20 for each FmD and PGmD of juvenile; n=20, 15 for FmD and PGmD of adult; n=20, 21 for FmD and PGmD of ChABC; n=10 for each FmD and PGmD of Tris Buffer; n=7 for each FmD and PGmD of human; n=35–50 each for FmDs and PGmDs in hetTECs). Cellular (n=10 for fetal PG; n=20 all other groups) and nuclear (n=25 for juvenile FmD; n=20 all other groups) strains were calculated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) by measuring the change in length of the cell long axis in the native fetal, juvenile, and adult tissues as a function of applied strain.

Strain mapping

To confirm triad analysis, adult bovine meniscus tissues (n=2) were prepared for mechanical testing as described above and analyzed using texture correlation. Cell nuclei were stained using 10 μM DRAQ-5® (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 30 min, then washed in 1X PBS. A 30 mN preload was applied after the sample was placed in the grips. Incremental strains of 1%, up to 4 or 9% were applied at a strain rate of 0.1%/sec. Z-stack confocal images were acquired at 0% strain and at each strain increment using a water-immersion 10X lens zoomed all the way out (FOV: 1,270.31 × 1,270.31 μm2; DRAQ-5: 633 nm/LP 650 nm). At the end of testing, tissue autofluorescent images were acquired using a 405 nm laser set at high power. Tested samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, cryo-sectioned, and stained with Alcian blue. Locations of the imaged regions were identified on histological slides by matching structural features between tissue auto-fluorescence and histology. To perform strain mapping, flattened the confocal z-stacks containing cell nuclei from each strain increment were analyzed via texture correlation using VIC-2D™ (Correlated Solutions, Columbia, SC). For hetTECs, the same images used to calculate ECM strain from nuclear triads were also processed by strain mapping using VIC-2D™.

Finite element modeling

For finite element (FE) analysis, a representative Alcian blue and Picrosirius red-stained histology section was used to generate a mesh of representative geometry consisting of a PGmD embedded in the FmD. The PGmD observed in the histology section was manually outlined and converted into a 2D FE mesh (FEBio)40 using a custom MATLAB program (S. Fig 13a). The FmD was modeled as a Holmes-Mow matrix reinforced with exponential power law fibers using material properties taken from the previous work on fibrocartilage.41 The PGmD was modeled as a Holmes-Mow matrix with a Donnan osmotic swelling parameter. Material properties for the PGmD were taken from the articular cartilage literature, where the mechanical behavior of articular cartilage is dominated by the PG matrix and osmotic swelling.25,26 To simulate the physiologic interface between PGmD and FmD (as observed in the SHG image, Fig. 1e), a transition zone that separated the PGmD and FmD was incorporated (S. Fig 13b). This zone was modeled as a Holmes-Mow matrix with a Poisson ratio equal to both PGmD and FmD. The transition zone matrix modulus (E) and non-linear stiffening term (β) were selected as the combination that best reproduced the experimental strain ratios ( ) of the juvenile meniscus at 10% strain. To simulate the effect of GAG digestion via ChABC treatment, the PGmD fixed charge density set to zero and the PGmD elastic modulus (E) was reduced by 98%, as described previously.27 The material properties for each region are summarized in S. Table 2.

Calcium signaling in native tissues and hetTECs

Fresh bovine juvenile menisci were obtained and prepared as described above. For hetTECs, the top layer of hetTEC was carefully peeled away using tweezers to expose the underlying FmD and PGmD tissue layer. Prior to mechanical testing and confocal imaging, cells were stained with the intracellular calcium indicator Cal-520™ AM (15 μ M; AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA) in 1X Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; with CaCl2, MgCl2, and no phenol red; Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) for 1 hour at 37°C. All samples were washed briefly in HBSS before imaging.

To monitor changes in intracellular calcium concentration in response to strain, tissue samples were gripped in the custom micromechanical test device mounted on a confocal microscope. A 30 mN preload was applied to remove tissue slack. Grip strains of 0 (n=5 tissues), 3 (n=6 tissues), 6 (n=5 tissues), and 9% (n=7 tissues) were applied at 0.1%/sec. For hetTECs, samples were stretched to grips strain of 6% at 0.1%/sec (n=3 per group). Before (i.e., baseline) and after strain application, time-series confocal images of the calcium signal was acquired every 4 seconds for 10 min using a 10X water-immersion lens (field-of-view: 900 × 900 μm2). The same groups of cells were tracked and imaged during and after strain. For hetTECs, cells were imaged in a plane located at 1/3 of the pellet height (determined from the z-stack), closest to the underlying scaffold surface (S. Fig 14). All samples were submerged in HBSS at room temperature throughout testing. For native tissues, the locations of putative PGmDs were confirmed by histology as above.

Nuclear shape and calcium signaling analysis

ImageJ was used to determine the percentage of responding cells, nuclear area (n=50 per group), and the nuclear aspect ratio (the ratio of the long axis to the short axis, n=50 per group). A custom MATLAB program16 was used to quantify temporal characteristics (peak amplitudes, durations, number of peaks in 10 min, and time between peaks) of the calcium oscillations. For native tissues, the baseline percentage of responding cells was pooled from all groups at 0% strain in both FmD and PGmD regions.

Statistical analysis

For normally distributed data, student’s t-test (two-tailed and unpaired), one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA was performed. For multiple comparisons, Tukey’s or Bonferroni post-hoc tests were performed, as indicated in the figure captions. For data that did not fit a normal distribution, Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal Wallis tests were performed. For non-parametric multiple comparison tests, a Bonferroni-Dunn’s post-hoc test was performed. To compare strains across multiple length scales, linear regression was performed between Lagrangian tissue vs. ECM strain, ECM strain vs. cell strain, and cell strain vs. nuclear strain for FmD and PGmD regions. The extra-sum-of-squares F-test was performed to compare the slopes of regression (i.e., average strain transfer ratios). Significance was set at p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Arjun Raj for assistance with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), Dr. Jeff Caplan and Dr. Sylvia Qu for assistance with confocal microscopy, Alison Marcozzi for assistance with histology, and John Peloquin for finite element model mesh generation. The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 EB02425 and the Penn Center of Musculoskeletal Disorders grant P30AR050950.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

WMH, SJH, TPD, JFD, CMM, LJS, RLD, RLM and DME designed the studies. WMH, SJH, TPD, JFD and CMM performed the experiments. WMH, SJH, TPD, JFD, CMM, LJS, RLD, RLM and DME analyzed and interpreted the data. WMH, SJH, RLM and DME drafted the manuscript, and all authors edited the final submission.

Code availability

Custom MATLAB programs used in this study are available upon request.

References

- 1.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:412–419. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nerurkar NL, et al. Nanofibrous biologic laminates replicate the form and function of the annulus fibrosus. Nat Mater. 2009;8:986–992. doi: 10.1038/nmat2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher MB, et al. Engineering meniscus structure and function via multi-layered mesenchymal stem cell-seeded nanofibrous scaffolds. J Biomech. 2015;48:1412–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baek J, et al. Meniscus tissue engineering using a novel combination of electrospun scaffolds and human meniscus cells embedded within an extracellular matrix hydrogel. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2015;33:572–583. doi: 10.1002/jor.22802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puetzer JL, Koo E, Bonassar LJ. Induction of fiber alignment and mechanical anisotropy in tissue engineered menisci with mechanical anchoring. J Biomech. 2015;48:1436–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker BM, et al. Sacrificial nanofibrous composites provide instruction without impediment and enable functional tissue formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14176–14181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206962109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han WM, et al. Macro-to microscale strain transfer in fibrous tissues is heterogeneous and tissue-specific. Biophys J. 2013;105:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upton ML, Gilchrist CL, Guilak F, Setton LA. Transfer of macroscale tissue strain to microscale cell regions in the deformed meniscus. Biophys J. 2008;95:2116–2124. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.126938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai JH, Levenston ME. Meniscus and cartilage exhibit distinct intra-tissue strain distributions under unconfined compression. Osteoarthr Cartil OARS Osteoarthr Res Soc. 2010;18:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruehlmann SB, Hulme PA, Duncan NA. In situ intercellular mechanics of the bovine outer annulus fibrosus subjected to biaxial strains. J Biomech. 2004;37:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott DM, Setton LA. Anisotropic and inhomogeneous tensile behavior of the human anulus fibrosus: experimental measurement and material model predictions. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:256–263. doi: 10.1115/1.1374202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connell GD, Guerin HL, Elliott DM. Theoretical and uniaxial experimental evaluation of human annulus fibrosus degeneration. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:111007. doi: 10.1115/1.3212104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham AC, Edwards CR, Odegard GM, Donahue TLH. Regional and fiber orientation dependent shear properties and anisotropy of bovine meniscus. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:2024–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang F, Sawhney AS, Lake SP. Different regions of bovine deep digital flexor tendon exhibit distinct elastic, but not viscous, mechanical properties under both compression and shear loading. J Biomech. 2014;47:2869–2877. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han WM, et al. Impact of cellular microenvironment and mechanical perturbation on calcium signalling in meniscus fibrochondrocytes. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;27:321–331. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v027a23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang F, Lake SP. Multiscale Strain Analysis of Tendon Subjected to Shear and Compression Demonstrates Strain Attenuation, Fiber Sliding, and Reorganization. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jor.22955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malaviya P, et al. An in vivo model for load-modulated remodeling in the rabbit flexor tendon. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2000;18:116–125. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attia M, et al. Alterations of overused supraspinatus tendon: A possible role of glycosaminoglycans and HARP/pleiotrophin in early tendon pathology. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:61–71. doi: 10.1002/jor.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell R, et al. Controlled treadmill exercise eliminates chondroid deposits and restores tensile properties in a new murine tendinopathy model. J Biomech. 2013;46:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell R, et al. ADAMTS5 is Required for Biomechanically-Stimulated Healing of Murine Tendinopathy. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jor.22398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott A, et al. Increased versican content is associated with tendinosis pathology in the patellar tendon of athletes with jumper’s knee. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008;18:427–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang VM, et al. Murine tendon function is adversely affected by aggrecan accumulation due to the knockout of ADAMTS5. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2012;30:620–626. doi: 10.1002/jor.21558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szczesny SE, Elliott DM. Interfibrillar shear stress is the loading mechanism of collagen fibrils in tendon. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2582–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chahine NO, Wang CCB, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Anisotropic strain-dependent material properties of bovine articular cartilage in the transitional range from tension to compression. J Biomech. 2004;37:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ateshian GA, Rajan V, Chahine NO, Canal CE, Hung CT. Modeling the matrix of articular cartilage using a continuous fiber angular distribution predicts many observed phenomena. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:061003. doi: 10.1115/1.3118773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canal Guterl C, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions of proteoglycans to the compressive equilibrium modulus of bovine articular cartilage. J Biomech. 2010;43:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker BM, Nerurkar NL, Burdick JA, Elliott DM, Mauck RL. Fabrication and modeling of dynamic multipolymer nanofibrous scaffolds. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:101012. doi: 10.1115/1.3192140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raj A, Tyagi S. Detection of individual endogenous RNA transcripts in situ using multiple singly labeled probes. Methods Enzymol. 2010;472:365–386. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)72004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat Methods. 2008;5:877–879. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plaas A, et al. Biochemical identification and immunolocalizaton of aggrecan, ADAMTS5 and inter-alpha-trypsin-inhibitor in equine degenerative suspensory ligament desmitis. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2011;29:900–906. doi: 10.1002/jor.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asai S, et al. Tendon progenitor cells in injured tendons have strong chondrogenic potential: the CD105-negative subpopulation induces chondrogenic degeneration. Stem Cells Dayt Ohio. 2014;32:3266–3277. doi: 10.1002/stem.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heo SJ, et al. Fiber stretch and reorientation modulates mesenchymal stem cell morphology and fibrous gene expression on oriented nanofibrous microenvironments. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:2780–2790. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0365-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauck RL, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Chondrogenic differentiation and functional maturation of bovine mesenchymal stem cells in long-term agarose culture. Osteoarthr Cartil OARS Osteoarthr Res Soc. 2006;14:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauck RL, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Regional multilineage differentiation potential of meniscal fibrochondrocytes: implications for meniscus repair. Anat Rec Hoboken NJ 2007. 2007;290:48–58. doi: 10.1002/ar.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu F, et al. Repair of dense connective tissues via biomaterial-mediated matrix reprogramming of the wound interface. Biomaterials. 2015;39:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DH, Martin JT, Elliott DM, Smith LJ, Mauck RL. Phenotypic stability, matrix elaboration and functional maturation of nucleus pulposus cells encapsulated in photocrosslinkable hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2015;12:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peltz CD, Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. Mechanical properties of the long-head of the biceps tendon are altered in the presence of rotator cuff tears in a rat model. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2009;27:416–420. doi: 10.1002/jor.20770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Driscoll TP, Cosgrove BD, Heo SJ, Shurden ZE, Mauck RL. Cytoskeletal to Nuclear Strain Transfer Regulates YAP Signaling in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biophys J. 2015;108:2783–2793. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA. FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134:011005. doi: 10.1115/1.4005694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs NT, Cortes DH, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM. Biaxial tension of fibrous tissue: using finite element methods to address experimental challenges arising from boundary conditions and anisotropy. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135:021004. doi: 10.1115/1.4023503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.