Abstract

Negative attitudes toward HIV medications may restrict utilization of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Indonesian prisons where many people living with HIV (PLH) are diagnosed and first offered ART. This mixed-method study examines the influence of medication attitudes on ART utilization among HIV-infected Indonesian prisoners. Randomly-selected HIV-infected male prisoners (n = 102) completed face-to-face in-depth interviews and structured surveys assessing ART attitudes. Results show that although half of participants utilized ART, a quarter of those meeting ART eligibility guidelines did not. Participants not utilizing ART endorsed greater concerns about ART efficacy, safety, and adverse effects, and more certainty that ART should be deferred in PLH who feel healthy. In multivariate analyses, ART utilization was independently associated with more positive ART attitudes (AOR = 1.09, 95 % CI 1.03–1.16, p = 0.002) and higher internalized HIV stigma (AOR = 1.03, 95 % CI 1.00–1.07, p = 0.016). Social marketing of ART is needed to counteract negative ART attitudes that limit ART utilization among Indonesian prisoners.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, HIV, Medication attitudes, Prisons, Stigma, Indonesia

Introduction

Indonesia faces the triple threat of high HIV prevalence, rising incidence, and low treatment coverage. With an estimated 76,000 new HIV infections annually, Indonesia has become the 8th largest contributor to new infections worldwide [1]. Indonesia has proactively sought to expand access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) through compulsory ART licensing and providing ART to patients at no cost [2]. Even so, HIV care can impose substantial financial hardship [3] and ART coverage in Indonesia remains the lowest in the Asia–Pacific region with a mere 5 % of Indonesia’s ~610,000 people living with HIV (PLH) currently prescribed ART [4]. PLH who bear the added stigma of addiction or incarceration may be even less likely to access or benefit from HIV treatment [5, 6].

HIV prevalence in Indonesian prisons, officially estimated at 1.1–6.5 % [7, 8], is several-fold higher than in communities [9]. Prisoners living with HIV are often people who inject drugs (PWID) who are incarcerated due to criminalization of drug use under Indonesian law. Although the structured prison setting offers opportunities to improve ART access and utilization [10–12], numerous individual and institutional factors may contribute to ART being delayed, declined, or discontinued in clinically eligible PLH, including a patient’s trust in physicians [13], belief in the personal necessity of ART [14], or readiness to commit to ART [15]. Prison overcrowding, opportunistic infections, and delayed ART initiation contribute to high HIV-related mortality in Indonesian prisons [16–18]. Providing ART to incarcerated PLH and proactively linking them to care after release are considered priorities for reducing Indonesia’s immense treatment gap and preventing onward transmission [1, 19].

A national plan seeks to improve ART access for Indonesia’s ~160,000 prisoners [20, 21], yet implementation has inadequately accounted for social-contextual factors that could impede ART utilization in prisons including patient health beliefs, attitudes toward treatment, [13, 22] and HIV stigma [23, 24]. Few studies have evaluated factors that influence ART utilization in Indonesia [25, 26], and none have done so in prisons where many PLH are diagnosed and given a choice about starting ART. Using a structured questionnaire and in-depth interviews, we therefore undertook and present a mixed method assessment of patient medication attitudes in 102 male PLH recruited from two large prisons in Jakarta. We also investigate how their attitudes influenced ART utilization during incarceration.

Theoretical Framework

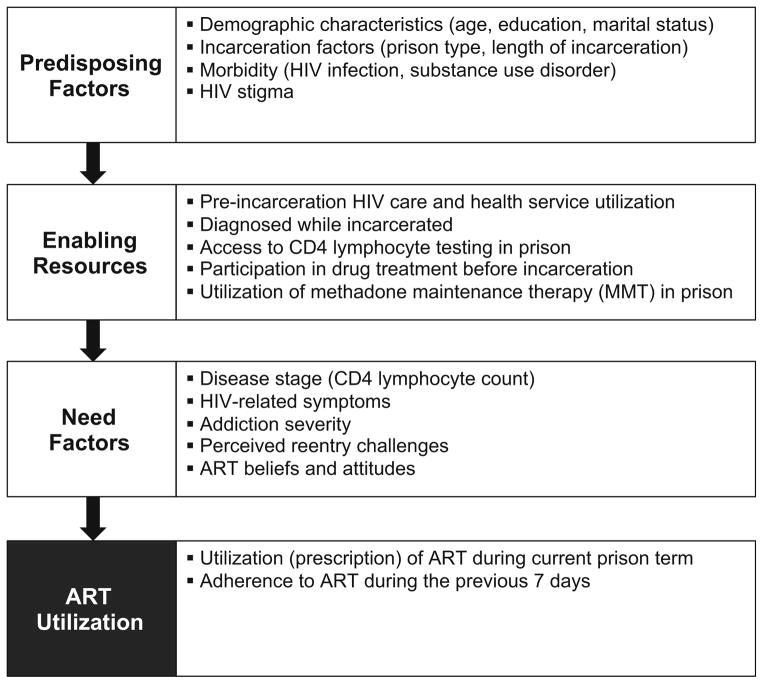

Our conceptual model was adapted from the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations [27] in which health service utilization is influenced by predisposing, enabling, and need factors. This model has been used to explain complex behaviors like ART acceptance and utilization [13] and retention in HIV care after prison release [28]. Figure 1 presents the behavioral model, which we adapted to include variables pertinent to our study population of incarcerated PLH. Predisposing factors are intrinsic individual and social-structural characteristics that influence ART utilization and included HIV stigma [29]. Enabling/disabling resources are individual and health care factors that influence ART utilization including access to HIV and addiction treatment. Need factors are self-perceived and objective health needs and included ART attitudes, which according to our model, comprise a set of modifiable beliefs about the efficacy, appropriateness, and safety of ART that can influence a patient’s readiness to begin using ART [30].

Fig. 1.

Behavioral model adapted for ART utilization among prisoners

Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to international guidelines for research with prisoners [31]. Participation decisions resulted neither in benefit nor punishment. Institutional Review Boards at Yale University and the University of Indonesia approved the research protocol and the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Directorate General of Corrections authorized the study. No prison staff members were present during screening, enrollment, or interviews, which were conducted in private rooms within prison clinics. For their contributed time, participants received a snack and small toiletry kit.

Study Design

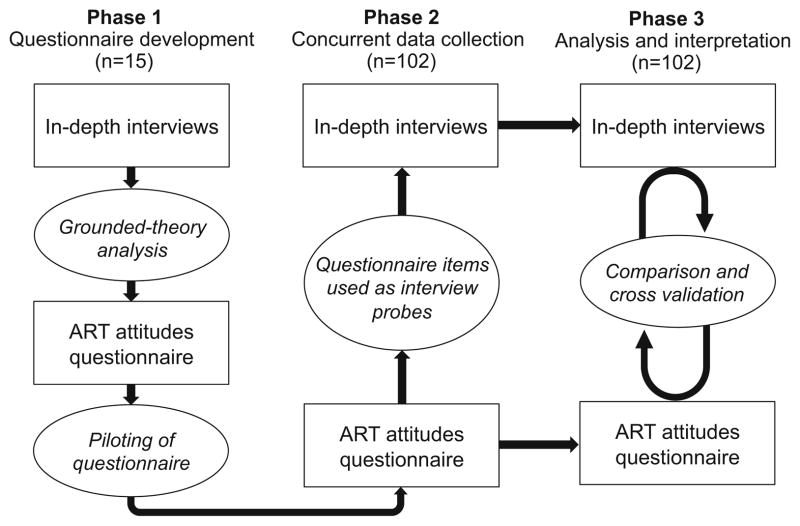

We conducted a mixed method study to examine the association between ART attitudes and ART utilization in incarcerated PLH, and to explore the mechanisms underlying ART utilization within these prison settings. Our choice of study design was guided by our intent to develop a quantitative measure of ART attitudes grounded in the Indonesian prison context. We therefore chose a convergent mixed method study design in which qualitative and quantitative data inform and build upon each other during data collection and analysis [32] to provide a multi-level perspective on medication attitudes among prisoners.

Figure 2 depicts our study design. During phase 1, we piloted an in-depth interview guide with 15 participants and analyzed transcripts to develop a structured ART Attitudes Questionnaire (ART-AQ). In phase 2, we administered the ART-AQ to 102 male participants (including the 15 participants who completed initial in-depth interviews), and used their responses to ART-AQ items as probes during subsequent interviews. For example, a participant who indicated strong agreement with the statement, “PLH who feel healthy don’t need to start ART” would have been asked during his in-depth interview to explicate this attitude. In phase 3, we compared interview and questionnaire data to interpret the study results.

Fig. 2.

Convergent mixed method study design

Indonesian Prison Setting

This study was conducted within two large Jakarta prisons including one specialized narcotics prison that houses prisoners charged with drug–related offenses [7, 8]. Table 1 shows characteristics of the two prisons, documenting extreme overcrowding and high HIV prevalence (11.2 and 13.9 %). The non-narcotics prison routinely tests all new inmates, while clinicians at the narcotics prison recommend HIV testing for symptomatic and high-risk patients. Confirmed HIV cases represent 4.7 % of the total inmate population at both sites, though HIV prevalence estimates suggest low case detection. At both sites, ART is provided within prison-based HIV clinics and prioritized for those with advanced HIV (WHO clinical stages 3–4) and TB co-infected prisoners [19]. Most frequently prescribed first-line ART includes zidovudine plus lamivudine with either nevirapine or efavirenz. ART is dispensed on weekdays as directly observed therapy at both facilities and is self-administered for evening and weekend dosing. Before initiating ART, patients meet with a counselor who provides information and assesses their readiness to begin ART. At the time of the study, ART was being prescribed to 40.4 % of HIV-infected prisoners, yet one third (35 %) of those meeting ART eligibility criteria (CD4 <350 cells/mL) were not prescribed it.

Table 1.

Description of selected prisons and prisoners at Jakarta research sites November 2013–May 2014

| Characteristic | Jakarta narcotics prison N (%) | Central Jakarta prison N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Population (% over capacity) | 3131 (415) | 1865 (306) |

| Prisoners on methadone maintenance therapy | 50 (1.6) | None |

| Estimated HIV prevalence among male prisoners | 435 (13.9)* | 208 (11.2)** |

| Known HIV cases | 136 (4.3) | 99 (5.3) |

| Underwent CD4 testing while incarcerated | 113 (83.0) | 63 (63.6) |

| Number of prisoners prescribed ART | 60 (44.1) | 35 (35.0) |

| Number eligible for ART (CD4 <350 cells/mL) | 67 (49.2) | 33 (33.3) |

| Number eligible for ART (CD4 <350 cells/mL) and prescribed ART | 45 (67.1) | 20 (60.6) |

ART antiretroviral therapy;

2012 data;

2011 data

Recruitment

Between November 2013 and May 2014, 102 incarcerated PLH were recruited from two prisons in Jakarta using random stratified sampling. Eligible participants were male, ≥18 years old, HIV-infected, fluent in Bahasa Indonesia, willing to participate in a voice-recorded interview, and able to give informed consent. A prison physician used medical records to compile a list of HIV-diagnosed patients. Proportionate stratification involved ART prescription (or not) within each of five CD4 count categories (<200, 200–350, 351–500, >500 cells/mL, and undefined). One quarter of PLH (25.2 %) had not yet undergone CD4 testing. A random number generator was used to select 60 prisoners (a proportional fixed number within each ART and CD4 strata) from each site who we invited to be screened for the study. Of 120 prisoners selected for screening, 7 were released, 2 died, 1 was in solitary confinement, and 1 escaped prison before screening. Two were ineligible and five refused further participation after screening, leaving 102 participants in the final sample. ART utilization in the final sample (50 %) was somewhat higher than at Jakarta Narcotics Prison (44.1 %) or Central Jakarta Prison (35.0 %) because those with low CD4 and not utilizing ART were more likely to decline enrollment.

In-depth Interviews and Translation

A structured interview guide consisting of 23 open-ended questions and probes was used to explore participant decisions to utilize ART while incarcerated. The interview guide was based on a review of existing literature and edited extensively by a survey research lab before being translated into Bahasa Indonesia by an expert panel, which included native Indonesian and English speakers, using a direct forward translation approach [33]. Examples of questions included, “What concerns did you have before starting ART”, and “What would have to change for you to feel ready to take ART”. We piloted the interview guide with 15 participants and made minor changes to reword questions. Native Indonesian-speaking interviewers underwent additional training in research ethics, psychosocial aspects of HIV/AIDS, and experiential role-playing in qualitative in-depth interviewing [34, 35]. Face-to-face interviews were voice-recorded and lasted about 60 min.

Study Measures

Dependent Variable

ART utilization, the main outcome, was defined as being currently prescribed ART by a physician while incarcerated which we ascertained from medical records and confirmed by participant self-report. Discrepancies between medical records and self-reported ART utilization (n = 2) were resolved by reviewing ART dispensing logs. We did not differentiate those initiating ART for the first time from those continuing ART that was initiated before incarceration. Self-reported ART adherence was assessed with a single question about the amount of ART (all, most, half, a little, none) a participant had consumed in the 7 days before the interview [36].

Independent Variables

Attitudes about antiretroviral therapy (ART) were assessed using the ART Attitudes Questionnaire (ART-AQ), a survey consisting of 22 Likert-type items that we developed by analyzing participant responses to open-ended questions about ART from the first 15 interviews (which included participants utilizing and not utilizing ART). Participants indicated their level of agreement from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree. Higher scores indicated more favorable attitudes toward ART. The ART-AQ was administered separately to each of the first 15 participants to assess understanding.

We conducted principal components analysis (PCA) with the original 22-item ART-AQ as a data reduction strategy to parsimoniously describe ART attitudes. The measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) was assessed to ensure that items would contribute usefully to PCA. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic was high (0.77) but the MSA for one item was <0.5 and was not included in subsequent analysis. Applying PCA to the remaining 20 items, we dropped an additional 6 items with low component loading (<0.4) and 3 items that had high loading (>0.4) on more than one component. PCA was applied to the remaining 12 items. Examination of the scree plot and initial Eigenvalues favored a single factor solution that explained 37.0 % of the variance. The remaining 12 items (marked with an * in Table 6) had good internal consistency (α = 0.83), and were used to create a composite variable, ART attitudes, in the regression predicting ART utilization.

Table 6.

Bivariate associations between ART attitudes and ART utilization (n = 102)

| Statement | Response | Utilizing ART in prison

|

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 51) N (%) | No (n = 51) N (%) | |||

| ART efficacy | ||||

| 1. The goal of taking ART is to reduce the amount of virus in the body | Agree | 42 (82.4) | 37 (72.5) | 0.236 |

| 2. Taking ART can help a person who has HIV stay healthy* | Agree | 51 (100) | 43 (84.3) | 0.003 |

| 3. ART can not really help people who have HIV* | Disagree | 45 (88.2) | 30 (58.8) | 0.001 |

| 4. Prayer is better than ART for controlling the virus* | Disagree | 29 (56.9) | 17 (33.3) | 0.017 |

| 5. There is no way to know for sure if ART is working | Disagree | 21 (41.2) | 10 (19.6) | 0.018 |

| Timing of treatment | ||||

| 6. PLWH who feel healthy don’t need to start ART* | Disagree | 38 (74.5) | 17 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| 7. PLWH do not need to start ART unless they feel sick* | Disagree | 48 (94.1) | 33 (64.7) | <0.001 |

| Side effects | ||||

| 8. Taking ART will cause a person’s skin to burn | Disagree | 13 (25.5) | 3 (5.9) | 0.006 |

| 9. Taking ART will cause me to have drug withdrawal | Disagree | 40 (78.4) | 29 (56.9) | 0.020 |

| 10. If I feel that ART makes me sick, I should take half the medicine.* | Disagree | 37 (72.5) | 18 (35.3) | <0.001 |

| 11. If I had side effects from ART, I would stop taking ART | Disagree | 28 (54.9) | 11 (21.6) | 0.001 |

| 12. ART works best if you take it some days but not other days* | Disagree | 46 (90.2) | 22 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Mixing drugs and medications | ||||

| 13. People should not take methadone and ART at the same time | Agree | 22 (43.1) | 11 (21.6) | 0.020 |

| 14. A person who plans to use heroin should not take ART | Disagree | 28 (54.9) | 24 (47.1) | 0.428 |

| Privacy for utilizing ART | ||||

| 15. I prefer not to take ART because I don’t want other prisoners to know I have HIV* | Agree | 7 (13.7) | 16 (31.4) | 0.033 |

| Intentions to remain in HIV care after release | ||||

| 16. A person not taking ART does not need to see a doctor for HIV* | Disagree | 42 (82.4) | 28 (54.9) | 0.003 |

| 17. It’s pointless to consume ART in prison, because it is too difficult to get the medicine after release* | Disagree | 43 (84.3) | 29 (56.9) | 0.002 |

| 18. I will probably be too busy to take ART after release* | Disagree | 35 (68.6) | 21 (41.2) | 0.005 |

| 19. I worry about paying for ART after release | Disagree | 27 (52.9) | 15 (29.4) | 0.016 |

| 20. I worry about finding a clinic near my house | Disagree | 32 (62.7) | 18 (35.3) | 0.006 |

| 21. I worry about getting a referral for ART | Disagree | 29 (56.9) | 14 (27.5) | 0.003 |

| 22. I worry about having transportation to the clinic* | Disagree | 43 (84.3) | 25 (49.0) | <0.001 |

p value significant at p < 0.05 or higher are given in bold

ART antiretroviral therapy;

items that contribute to the composite variable, ART attitudes

HIV stigma was measured using a modified version of the Internalized HIV Stigma Scale [37], which we adapted for the Indonesian prison setting [38]. Participants indicated the frequency with which they experienced HIV-related stigma on a 5 point Likert type response scale (never, seldom, sometimes, often, always). Specific changes included substituting items measuring drug use-related stigma for 2 items assessing parenting stigma and changing “co-workers” to “other prisoners” in one item. We computed a modified 4-factor solution with stigma subscales measuring stereotypes, addiction stigma, disclosure concerns, and social relationships. We transformed scores linearly on a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stigma. Overall reliability was high (α = 0.90).

Other measures potentially associated with ART utilization were selected using our conceptual model and included socio-demographic characteristics, incarceration factors, and established measures of pre-incarceration drug use and drug treatment [39]. HIV clinical care factors included self-reported ART utilization before incarceration and most recent CD4 cell count obtained from medical records.

Analytical Plan

Quantitative Analysis of Variables Associated with ART Utilization

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (Version 19.0) to examine bivariate (Chi square and Student t test) and multivariate correlates of ART utilization, the main dependent variable. We conducted bivariate analyses of dichotomized ART-AQ items (using agree or disagree as reference categories) to examine associations between individual ART-AQ items and ART utilization presented in Table 6. We next examined bivariate and multivariate associations between ART attitudes (as a single continuous variable) and ART utilization. Given our limited sample size, parsimony of the final model was a concern. We included variables with a bivariate initial association of p < 0.05 into preliminary logistic regression and then proceeded with manual stepwise elimination of 3 variables (ART utilization before arrest, diagnosis in prison, and HIV status disclosure) that were strongly collinear with other independent variables, while maintaining those of known conceptual importance to ART utilization. To compare candidate models we used Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) which penalizes model complexity [40]. Low (≤1.5) VIF values indicated low likelihood of collinearity among dependent variables in the final model.

Qualitative Analysis of In-Depth Interviews

To enhance interpretive validity, interviewers underwent a structured debriefing immediately following each interview [41]. Voice-recorded interviews were transcribed in Bahasa Indonesia and translated into English by experienced bilingual researchers. Transcripts were entered into NVivo Qualitative Research Software [42] for analysis and coded by three researchers (GJC/APM/MI) using a grounded theory approach [43–45]. We reviewed transcripts preliminarily in Bahasa Indonesia to classify and code statements describing ART attitudes. Individual survey items were developed by paraphrasing direct participant quotations. We reviewed subsequent transcripts in a constant comparative process [43] to identify patterns in the data and continuously refine analytic categories. A codebook was used to ensure coding consistency. We examined code frequency and relationships and compared these data with ART-AQ responses. Five categories of ART attitudes were chosen for final qualitative analysis based on estimated frequency of occurrence [46]. Exemplars were selected that illustrated the full range of participant attitudes influencing ART utilization.

Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Findings

Further integration of the questionnaire and interview findings occurred during data analysis and interpretation (Fig. 2). We compared interviews and surveys in an iterative process to clarify areas of congruence and divergence in findings. In-depth interview data was subsequently used to strengthen insights into the mechanisms underlying statistical associations between ART attitudes and utilization.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Bivariate Associations with ART Utilization

Participant characteristics and bivariate associations with ART utilization are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Half of study participants (50.0 %) were currently utilizing ART. Of these, 45 (88.2 %) were initiating ART for the first time while 6 (11.7 %) were continuing ART that was started before incarceration. Most study participants had not finished high school (54.9 %), were living with family (71.6 %), and employed (66.3 %) before incarceration. About half (53.9 %) were incarcerated in a narcotics prison. Most participants used heroin (68.6 %), and injected drugs (64.7 %) immediately before incarceration. Yet few (20.5 %) had ever participated in drug treatment and fewer (16.7 %) were taking methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) while incarcerated.

Table 2.

Bivariate demographic, incarceration, and drug use associations with ART utilization (n = 102)

| Characteristic | (n = 102) N (%) | Utilizing ART in prison

|

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 51) N (%) | No (n = 51) N (%) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Mean years of age (SD) | 31.3 ± 5.7 | 32.6 ± 5.5 | 30.1 ± 5.8 | 0.025 |

| Finished high school | 46 (45.1) | 27 (52.9) | 19 (37.3) | 0.111 |

| Married before incarceration | 32 (31.4) | 11 (21.6) | 21 (41.2) | 0.033 |

| Living with family before incarceration | 73 (71.6) | 34 (66.7) | 39 (76.5) | 0.272 |

| Employed or self-employed | 67 (66.3) | 31 (62.0) | 36 (70.6) | 0.361 |

| Income from drug trafficking | 35 (34.3) | 19 (37.3) | 16 (31.4) | 0.532 |

| Incarceration factors | ||||

| Recruited from Jakarta narcotics prison | 55 (53.9) | 33 (64.7) | 22 (43.1) | 0.029 |

| Incarcerated ≥2 years | 63 (61.8) | 38 (74.5) | 25 (49.0) | 0.008 |

| Drug use and needle sharing (3 months before arrest) | ||||

| Any drug use | 100 (98.0) | 51 (100) | 49 (96.1) | 0.153 |

| Heroin use | 70 (68.6) | 36 (51.4) | 15 (46.9) | 0.670 |

| Drug injection | 66 (64.7) | 34 (66.7) | 32 (62.7) | 0.679 |

| Daily drug injection | 57 (55.9) | 30 (58.8) | 27 (52.9) | 0.550 |

| Any needle sharing | 36 (35.3) | 17 (33.3) | 19 (37.3) | 0.709 |

| Ever inject drugs in jail/prison | 56 (54.9) | 29 (59.2) | 27 (52.9) | 0.530 |

| Addiction and drug treatment | ||||

| Ever tried to “cut back” or “stop” using | 72 (70.5) | 39 (76.5) | 33 (67.3) | 0.310 |

| Ever participate in drug treatment | 21 (20.5) | 13 (25.5) | 8 (16.3) | 0.332 |

| Drug withdrawal after last arrest | 66 (64.7) | 35 (68.6) | 31 (60.8) | 0.407 |

| Currently taking methadone in prison | 17 (16.7) | 9 (17.6) | 8 (15.7) | 0.790 |

p value significant at p < 0.05 or higher are given in bold

SD standard deviation

Table 3.

Bivariate clinical, stigma, and ART attitude associations with ART utilization (n = 102)

| Characteristic | (n = 102) N (%) | Utilizing ART in prison

|

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 51) N (%) | No (n = 51) N (%) | |||

| HIV care factors | ||||

| ≤1 year since HIV diagnosis | 35 (34.3) | 11 (21.6) | 24 (47.1) | 0.007 |

| Diagnosed in jail/prison | 79 (77.5) | 34 (66.7) | 17 (33.3) | 0.009 |

| Diagnosed during the current prison term | 70 (68.6) | 30 (58.8) | 40 (78.4) | 0.033 |

| Regular medical care before incarceration | 12 (11.8) | 9 (17.6) | 3 (5.9) | 0.073 |

| Taking ART before incarceration | 6 (5.9) | 6 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 0.018 |

| CD4 testing in prison | ||||

| Underwent CD4 testing while incarcerated | 84 (82.4) | 47 (92.2) | 33 (64.7) | 0.001 |

| <350 cells/mL | 49 (48.0) | 35 (68.6) | 14 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| <200 cells/mL | 26 (25.5) | 19 (37.3) | 7 (13.7) | 0.006 |

| HIV stigma and disclosure | ||||

| Mean HIV stigma score (SD) | 40.5 ± 19.8 | 45.1 ± 21.3 | 35.9 ± 17.2 | 0.019 |

| Disclosed HIV status to someone outside prison | 56 (54.9) | 34 (72.3) | 22 (46.8) | 0.012 |

| ART attitudes | ||||

| Mean ART attitudes score (SD) | 53.1 ± 11.0 | 58.7 ± 9.5 | 47.4 ± 9.4 | <0.001 |

p value significant at p < 0.05 or higher are given in bold

SD standard deviation

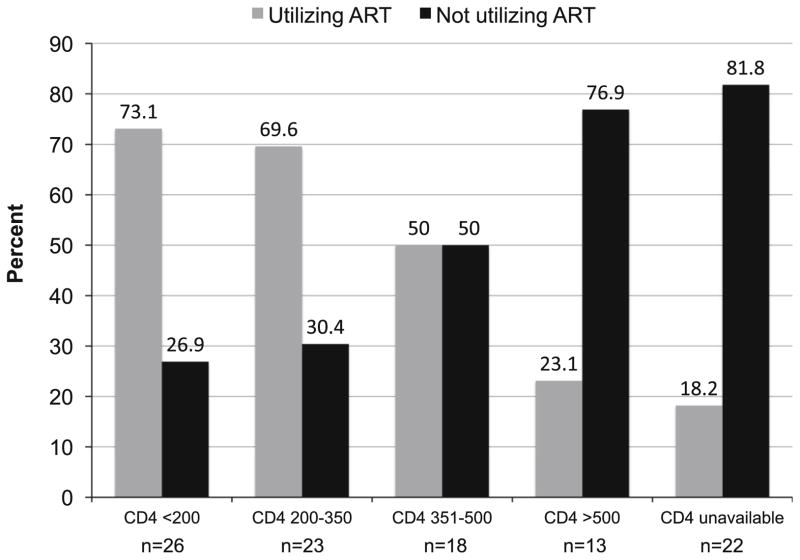

Most participants (68.6 %) were diagnosed with HIV during the current incarceration. Few of those diagnosed before incarceration reported utilizing HIV care (37.5 %) or ART (18.7 %) before incarceration. Figure 3 shows ART utilization by CD4 lymphocyte count. Nearly half of participants (48 %) had CD4 <350 cells/mL, of whom a third (31.4 %) were not utilizing ART. Some participants (17.6 %) had not yet undergone CD4 testing. The mean overall stigma score (40.5 ± 19.8) indicated that on average participants endorsed items describing perceptions or experiences of HIV stigma slightly less often than sometimes (mean score of 50). About half of participants (54.9 %) had disclosed their HIV status to someone outside of prison.

Fig. 3.

ART utilization by CD4 lymphocyte count

Participants utilizing ART while incarcerated were older (Mean = 32.6 vs. 30.1 years, p = 0.025) and less likely to be married (21.6 vs. 41.2 %, p = 0.03). Participants from the narcotics prison were more likely to be utilizing ART (64.7 vs. 43.1 %, p = 0.02) as were those incarcerated longer than 2 years (74.5 vs. 49.0 %, p = 0.008). Participants were more likely to be utilizing ART in prison if they were diagnosed (41.2 vs. 21.6 %, p = 0.03) or utilizing ART (5.9 vs. 0 %, p = 0.018) before incarceration.

Participants utilizing ART were more likely to have undergone CD4 testing while incarcerated (92.2 vs. 64.7 %, p = 0.001), and to have confirmed CD4 <350 cells/mL (68.6 vs. 27.4 %, p < 0.001) (Table 3). Participants utilizing ART had a higher mean stigma score compared to those not utilizing ART (Mean = 45.1 v. 35.9, p = 0.019), but were more likely to have disclosed their HIV status to someone outside of prison (72.3 vs. 46.8 %, p = 0.012). Multiple correlations are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlations between ART attitudes and other factors associated with ART utilization

| Variable | ART attitudes | HIV stigma | married | incarcerated in narcotics prison | incarcerated ≤2 years | years since HIV diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV stigma | 0.076 | |||||

| Married | −0.224* | 0.031 | ||||

| Incarcerated in narcotics prison | 0.236* | 0.229* | −0.138 | |||

| Incarcerated ≤2 years | −0.193 | 0.018 | 0.120 | −0.285** | ||

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 0.301** | 0.151 | −0.126 | 0.050 | −0.168 | |

| Underwent CD4 testing in prison | 0.363** | −0.065 | −0.159 | 0.233* | −0.274** | 0.218* |

| CD4 ≤350 cells/mL | 0.445** | 0.021 | −0.058 | 0.259** | −0.272** | 0.188 |

ART antiretroviral therapy;

correlation significant at 0.05 level (2-tailed);

correlation significant at 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Multivariate Associations with Antiretroviral Therapy Utilization

Table 5 shows unadjusted and adjusted associations with ART utilization during incarceration. ART utilization during incarceration was significantly associated with higher HIV stigma (AOR = 1.03, 95 % CI 1.00–1.07, p = 0.016) and higher ART attitudes (AOR = 1.09, 95 % CI 1.03–1.16, p = 0.002) after controlling for other individual and institutional factors.

Table 5.

Independent and multivariate associations of antiretroviral therapy utilization among prisoners (n = 102)

| Variable | UOR | 95 % CI | p value | AOR | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | 0.39 | 0.16–0.93 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.17–1.71 | 0.299 |

| Incarcerated in a narcotics prison | 2.41 | 1.08–5.36 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.28–2.68 | 0.812 |

| Incarcerated ≤ 2 years | 0.32 | 0.14–0.75 | 0.009 | 0.46 | 0.14–1.46 | 0.188 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 1.27 | 1.08–1.50 | 0.004 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.36 | 0.293 |

| Underwent CD4 testing in prison | 6.40 | 1.98–20.67 | 0.002 | 2.15 | 0.43–10.52 | 0.345 |

| CD4 ≤ 350 cells/mL | 5.78 | 2.46–13.57 | <0.001 | 2.40 | 0.73–7.90 | 0.149 |

| HIV stigma | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.016 |

| ART attitudes | 1.09 | 1.05–1.14 | <0.001 | 1.09 | 1.03–1.16 | 0.002 |

p value significant at p < 0.05 or higher are given in bold

ART antiretroviral therapy, UOR unadjusted odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Attitudes Toward Antiretroviral Therapy

Integration of survey and in-depth interview data revealed key differences in ART attitudes among those utilizing and not utilizing ART. Table 6 shows bivariate associations between ART attitudes and ART utilization. Participants not utilizing ART indicated lower (more negative) ART attitudes across nearly every attitudinal domain assessed by the questionnaire and had lower composite ART attitude scores compared to participants utilizing ART (Mean = 47.4 vs. 58.7, p < 0.001). ART attitudes were lowest among participants not utilizing ART who had not yet undergone CD4 testing, and highest (most favorable) among those utilizing ART with documented CD4<350. Similarly, the meanings that participants attributed to ART were deeply influenced by their beliefs concerning their own health status and observations of other prisoners utilizing ART. Participants not utilizing ART often perceived ART as ineffective or unnecessary in patients who “feel healthy” and worried that ART could cause adverse effects or dependency.

Efficacy of Antiretroviral Therapy

Most participants utilizing (82.4 %) and not utilizing ART (72.5 %) agreed that the purpose of ART was to control HIV replication rather than to cure HIV infection (p = 0.236). As one participant said, “The function of the medicine is to make the germs inside of you sleep.” (36 year-old, CD4 <200, not utilizing ART)

Participants utilizing ART were more likely than those not utilizing ART to agree that ART could help PLH maintain their health (100 vs. 84.3 % vs., p = 0.003). Among those not utilizing ART, the knowledge that ART did not “cure” HIV infection was sometimes interpreted to mean that ART was ineffective or unnecessary:

“If there was a medicine to treat HIV, I would take it. But now there is none. From the news I heard that HIV medicine has not been discovered.” (30 year-old, CD4 350–500, not utilizing ART)

Participants not utilizing ART were more likely to agree that prayer to God for intervention was more effective than ART for controlling the virus (33.3 vs. 56.9 % p = 0.017). As one participant opined:

“I believe that everything illness, health, age – only Allah knows. You don’t need medicine. If God says ‘You have a long life,’ you will.” (24 year-old, CD4 200–350, not utilizing ART)

Meanwhile, participants utilizing ART were more confident that ART efficacy could be objectively monitored (41.2 vs. 19.6 %, p = 0.018), but sometimes interpreted switching of ART regimens and information about “drug resistance” to mean that ART might only be effective for PLH who were naturally “compatible”.

Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy

Participants not utilizing ART were more likely to think that PLH should defer ART until they feel sick (94.1 vs. 64.7 %, p <0.001), and that PLH who feel healthy do not need to start ART (74.5 vs. 33.3 %, p < 0.001). As one participant who had previously taken ART said,

“Because I was getting better I asked the doctor to stop ARV. I was healthy again, no longer weak, and able to do my usual activities. If it gets severe and I can no longer walk on my own, then my friends will carry me to the clinic. When I get to that point, I will start ARV again.” (28 year-old, CD4 350–500, not utilizing ART)

Those who had not yet undergone CD4 testing expressed the most ambivalence about when to start ART, but said they wanted to begin ART before their health deteriorated.

Side Effects and Safety of Antiretroviral Therapy

Interview and survey responses indicated substantial concerns within both groups of participants about ART safety and adverse effects, especially “itching”, “burning”, or “darkening” of the skin. Those not utilizing ART were more likely to worry that ART could cause burning of the skin (5.9 vs. 25.5 %, p = 0.006) and more likely to interpret undesirable side effects as signs of ART “incompatibility.” As one informant explained, “I told the doctor I don’t want to take ARV because I think if it’s not compatible the skin will get blackened and burned.” (29 year-old, CD4 350–500, not utilizing ART)

Participants not utilizing ART also expressed concerns that ART could cause weight loss or physical deterioration, “Other people who have taken ARV, it didn’t get rid of their disease, but made them deteriorate. Instead of getting fatter, their body shrinks.” (28-year-old, CD4 200–350, not utilizing ART) Others interpreted the need for strict ART adherence to mean that they would become physically dependent on ART.

“I don’t want to become dependent on that medicine. Not afraid exactly. But for sure I will become dependent if I take it. It causes dependency.” (31 year-old, CD4 350–500, not utilizing ART)

Participants utilizing ART expressed stronger intentions to continue ART despite side effects and disagreed more often that reducing or stopping ART was an appropriate strategy for managing medication side effects (54.9 vs. 21.6 %, p < 0.001).

Mixing of Antiretroviral Therapy and Medications

Participants classified ART, methadone, and TB treatments as “strong medicine” and worried that “mixing” them could be harmful. Participants utilizing ART were more likely to agree that co-administration of ART and methadone should be avoided (43.1 vs. 21.6 %, p = 0.02). Those not utilizing ART, however, were more likely to feel that ART could precipitate withdrawal from heroin or methadone (56.9 vs. 78.4 %, p = 0.02), and a few believed that “mixing” ART and methadone could be lethal.

“I’m afraid that my body will not be strong enough because I know that methadone is strong medicine, and ARV is even stronger. I saw that my friends who took both medicines died.” (34 year-old, CD4 < 200, not utilizing ART)

Although we did not see an association between ART utilization and beliefs about mixing of ART and heroin (54.9 vs. 47.1 %, p = 0.42), several participants indicated during in-depth interviews that ongoing drug use in prison could discourage ART initiation.

Privacy for Antiretroviral Therapy Administration

Participants not utilizing ART more often agreed that privacy concerns in prison could limit ART utilization (31.4 vs. 13.7 %, p = 0.03). Participants taking ART said that administration of ART could be stigmatizing.

“Sometimes when I take my medicine in front of the boys I feel awkward. I take the medicine and I just drink it immediately without anybody noticing. I don’t want to show them. I don’t want other people to know. I don’t want them to have this view about me. I tell them, it’s just vitamins.” (27 year-old, utilizing ART)

Other participants, however, said that disclosing their HIV status to other incarcerated PLH fostered social support that helped them to accept and adhere to ART. None identified privacy concerns as a reason for refusing ART or missing doses.

Intentions to Remain in Care After Release

Participants currently utilizing ART were less likely to believe that they would be “too busy” to take ART after release (68.6 vs. 41.2 %, p = 0.005) and less likely to endorse that PLH not taking ART do not need to see a doctor for HIV care (82.4 vs. 54.9 %, p = 0.003).

“I don’t even think about seeing the doctor outside of prison. It’s not that I’m afraid it will be expensive. Outside prison, I will be busy working.” (36 year-old, CD4 < 200, not utilizing ART)

Participants utilizing ART also anticipated fewer challenges accessing ART after release and were less likely to worry about being able to pay for ART (52.9 vs. 29.4 %, p = 0.01) or have transportation to a clinic (84.3 vs. 49.0 %, p < 0.001) after release.

Discussion

This mixed method study, the first to examine ART utilization among Indonesian prisoners, provides new insights into the influential role of ART attitudes on ART utilization among prisoners. In this sample of incarcerated and mostly newly diagnosed PLH, ART utilization was high but fell below optimal coverage. ART utilization among participants with confirmed CD4 <350 cells/mL was 68.6 %, nearly four-fold higher than the national average (17.6 %) [4]. Nonetheless, many patients with low CD4 counts were still not utilizing ART. Using a locally developed scale, we documented a strong relationship between individual ART attitudes and ART utilization that persisted after controlling for other individual and institutional factors. Our findings show that while predisposing factors and enabling resources, which include prison health services, may be important initial determinants of ART utilization, these factors are overpowered by instilled negative attitudes about ART. Negative ART attitudes appear to undermine individual and institutional factors that would ordinarily promote ART, and extensively restrict use of ART during incarceration even among those with severely compromised immunity.

The observed association between ART attitudes and ART utilization may operate through individual acceptance of ART, or a patient’s decision to act in accordance with a health care provider’s recommendation to initiate ART. Other studies have suggested that individual ART acceptance is an important determinant of initial ART prescription and utilization [15]. Many structural barriers to ART utilization are removed in the prison setting, yet others, which are unique to prisons, including violence and hopelessness, can discourage ART utilization [13, 47, 48]. Although our cross-sectional study design did not permit us to determine whether ART attitudes predict ART utilization, in-depth interview data strongly suggests that concerns about ART safety and adverse effects may weaken ART acceptance and restrict utilization among some clinically eligible prisoners. Among those not utilizing ART, we found more favorable ART attitudes in those with more advanced HIV compared to those who had not yet undergone CD4 testing. This finding suggests that counseling and provider engagement, which are typically prioritized for those with advanced HIV, could reduce negative ART attitudes and improve acceptance. Alternatively, peers who had successfully accessed and utilized ART could be deployed to improve care engagement [49, 50].

In this study, concerns about ART safety and efficacy which can limit ART acceptance and utilization [51, 52] were amplified through direct contact with other prisoners who are experiencing adverse effects including symptoms of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Delayed ART initiation and short-term adverse effects related to nevirapine-based regimens, which have been linked to more adverse medication events than efavirenz-based regimens [53], contribute to negative ART attitudes. Earlier initiation of ART, improved symptom management, and prescription of better tolerated agents may help reduce ART adverse effects and consequently contribute to improving ART acceptability [54]. Routine laboratory monitoring (e.g. CD4 testing) would result in more timely ART initiation among those ready to start ART, lead to more appropriate medication selection, and provide crucial feedback about ART efficacy. Concerns that ART could precipitate withdrawal or be harmful if “mixed” with methadone, which although available in some Indonesian prisons may be highly stigmatized [55], could lead patients to skip doses or stop treatment [56]. Increased coordination between HIV care and addiction treatment is needed to address interactive toxicity beliefs and proactively adjust methadone dose when starting ART to prevent symptoms of withdrawal [57].

Findings suggest the need for intervention strategies that counteract negative attitudes toward ART among incarcerated PLH. The perception that ART utilization signifies end-stage AIDS [58], which some prisoners use to rationalize ART deferral, needs to be discredited. At present, many incarcerated PLH are alarmed by ART messages leading to avoidance behaviors and discouraging ART utilization. Social marketing strategies that appeal to individual goals and focus on the personal rewards of treatment have been found to have a more lasting impact on behaviors than messages that frighten or emphasize avoiding negative health consequences [59]. Compelling new findings from the START trial underscore that there are important clinical benefits to starting ART at any CD4 count, even at greater than 500 cells/mL, leading to removal of restrictions about CD4 eligibility criteria for initiating ART [60]. Peer-driven interventions that improve HIV treatment literacy and confer resistance to negative attitudes may be especially useful in prison settings where HIV, drug use, and negative attitudes are concentrated, and also effective for reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors after prison release [49, 50, 61].

Importantly, our findings show higher perceived HIV stigma among those utilizing ART who had been diagnosed prior to incarceration. Possibly this association may reflect the greater exposure to negative public attitudes and enacted stigma in the period in which they lived in the community [62]. Participants, however, also voiced fears that taking ART in prison could subject them to harassment and discrimination—a finding that echoes other qualitative research showing that prisoners may hide their HIV status or refuse ART to prevent involuntary disclosure and avoid HIV-related stigma in prisons [23, 47]. This result suggests the need for greater privacy for medical care and dispensing medications in these prisons.

Finally, though a number of important findings emerged within this study that provide important future directions for health care delivery in prisoners and implications for future research, there are some notable limitations. First, while the sample is relatively small for an epidemiological study, it is actually large for most mixed method studies. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study cannot imply causality, but only inferences. Last, although our sample of HIV-infected prisoners was randomly selected, prisoners who did not inject drugs were a minority of the study participants, resulting in some restricted generalizability for all HIV-infected prisoners. This concern, however, is minor given the concentration of HIV among key populations in Indonesia. Notwithstanding these limitations, this is the largest mixed method study examining attitudes toward ART in HIV-infected prisoners in Asia and provides important insights for future interventions in order to improve health outcomes along the HIV treatment cascade.

Conclusion

Negative ART attitudes represent an important potential barrier to progression along the HIV treatment cascade in Indonesian prisons where many PLH are diagnosed and given their first opportunity to start ART. Concerns about ART safety and efficacy, and the belief that ART is not necessary for PLH to feel healthy, may limit ART acceptance and utilization by incarcerated PLH—even those with severely compromised immunity. Social marketing of ART is necessary to counteract negative attitudes, encourage ART initiation at higher CD4 counts, and improve health outcomes. Although individual factors were the main focus of this study, future research should consider provider and institutional factors that influence ART utilization.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported through a Fulbright Senior Scholar Award in Global Health from the J. William Fulbright Commission, U.S. State Department. This publication resulted in part from funding provided by the Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI 082151) supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM, and from NIH awards for career development (NIDA K24 DA017072) and training (T32 GM07205, F30 DA039716, D43 TW001419) and (R25 TW009338) funded by NIAID and Fogarty International Center. We thank study participants for generously sharing their time and experiences. We thank, Swasti Wulan, Budhi Mulyadi and Herlia Yuliantini for research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge operational support from the Directorate General of Corrections, Republic of Indonesia, especially Akbar Hadi Prabowo, and Hetty Widiastuti. We also thank Nurlan Silitonga, Cindy Hidayati, Alia Hartanti, David Shenman, Suzanne Blogg (HIV Cooperation Programme for Indonesia); Kathleen Norr and Colleen Corte (University of Illinois at Chicago); Elly Nurachmah, Dewi Irawaty, and Junaiti Sahar (Universitas Indonesia).

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The gap report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigg M. Indonesia acts to over-ride patents in HIV drugs. Reuters. 2012 (archived by Webcite® 2014 Oct 27 at: http://webcitation.org/6TdV3ARyB)

- 3.Riyarto S, Hidayat B, Johns B, Probandari A, Mahendradhata Y, Utarini A, et al. The financial burden of HIV care, including antiretroviral therapy, on patients in three sites in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(4):272–82. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV in Asia and the Pacific. 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milloy MJ, Montaner J, Wood E. Barriers to HIV treatment among people who use injection drugs: implications for ‘treatment as prevention’. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(4):332–8. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328354bcc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westergaard RP, Ambrose BK, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Provider and clinic-level correlates of deferring antiretroviral therapy for people who inject drugs: a survey of North American HIV providers. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-15-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Directorate of Corrections. HIV and HCV prevalence and risk behavior study in Indonesian narcotics prisons. Jakarta: Directorate of Corrections, Ministry of Law and Human Rights, Republic of Indonesia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Directorate of Corrections. HIV and syphilis prevalence and risk behavior study among prisoners and detention centres in Indonesia. Jakarta: Directorate of Corrections, Ministry of Law and Human Rights, Republic of Indonesia; 2010. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/HSPBS_2010_final-English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National AIDS Commission, Indonesia. Republic of Indonesia country report on the follow up to the declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS (United Nations General Assembly Special Session) Reporting period 2010–2011. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer JP, Chen NE, Springer SA. HIV treatment in the criminal justice system: critical knowledge and intervention gaps. AIDS Res Treat. 2011:680617. doi: 10.1155/2011/680617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of human immunodeficiency virus treatment during incarceration: viral suppression at the prison gate. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):721–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwadz M, Applegate E, Cleland C, Leonard NR, Wolfe H, Salomon N, et al. HIV-infected individuals who delay, decline, or discontinue antiretroviral therapy: comparing clinic- and peer-recruited cohorts. Front Public Health. 2014;2:81. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer L, Valverde EE, Raiford JL, Weiser J, White BL, Skarbinski J. Clinician perspectives on delaying initiation of antiretroviral therapy for clinically eligible HIV-infected patients. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(3):245–54. doi: 10.1177/2325957414557267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gokkon B. The Jakarta Globe. 2014. Inmates with HIV Told to See the Shrink. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djauzi S. Health situation in Indonesian penitentiary. Acta Med Indones. 2009;41(Suppl 1):4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelwan EJ, Diana A, van Crevel R, Alam NN, Alisjahbana B, Pohan HT, et al. Indonesian prisons and HIV: part of the problem, part of the solution? Acta Med Indones. 2009;41(Suppl 1):52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Helath, Indonesian. Permenkes No. 21 Tahun 2013 Penanggulangan HIV/AIDS (HIV/AIDS countermeasures) Jakarta: Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Directorate of Corrections. National action plan for control of HIV-AIDS and drug abuse in correctional units in Indonesia 2010–2014. Jakarta: Directorate of Corrections, Ministry of Law and Human Rights; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winarso I, Irawati I, Eka B, Nevendorff L, Handoyo P, Salim H, et al. Indonesian national strategy for HIV/AIDS control in prisons: a public health approach for prisoners. Int J Prison Health. 2006;2(3):243–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.White BL, Wohl DA, Hays RD, Golin CE, Liu H, Kiziah CN, et al. A pilot study of health beliefs and attitudes concerning measures of antiretroviral adherence among prisoners receiving directly observed antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(6):408–17. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Gamble KA, Kelkar K, Khuanghlawn P. Inmates with HIV, stigma, and disclosure decision-making. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(2):258–68. doi: 10.1177/1359105309348806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrinopoulos K, Figueroa JP, Kerrigan D, Ellen JM. Homophobia, stigma and HIV in Jamaican prisons. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(2):187–200. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.521575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iskandar S, de Jong CAJ, Hidayat T, Siregar IMP, Achmad TH, van Crevel R, et al. Successful testing and treating of HIV/AIDS in Indonesia depends on the addiction treatment modality. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:329–36. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S37625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver ER, Pane M, Wandra T, Windiyaningsih C, Herlina SG. Factors that influence adherence to antiretroviral treatment in an urban population, Jakarta, Indonesia. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, Fu J, Brown SE, Vagenas P, et al. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S156–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0372-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–73. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazzarini Z, Altice FL. A review of the legal and ethical issues for the conduct of HIV-related research in prisons. AIDS Public Policy J. 2000;15(3–4):105–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cresswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Office of behavioral and social sciences research (OBSSR) NIoHN, editor. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behling O, Law KS. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: problems and solutions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spradley JP. The ethnographic interview. Philadelphia: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, Inc; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeo A, Legard R, Keegan J, Ward K, McNaughton NC, Lewis J. In-depth interviews. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNaughton NC, Ormston R, editors. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014. pp. 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg KM, Wilson IB, Li X, Arnsten JH. Comparison among antiretroviral adherence questions. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):461–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9864-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sayles JN, Hays RD, Sarkisian CA, Mahajan AP, Spritzer KL, Cunningham WE. Development and psychometric assessment of a multidimensional measure of internalized HIV stigma in a sample of HIV-positive adults. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):748–58. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culbert GJ, Earnshaw VA, Swasti Wulanyani NM, Wegman MP, Waluyo A, Altice FL. Correlates and experiences of HIV stigma in prisoners living with HIV in Indonesia: a mixed-method analysis. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simpson DD, Joe GW, Knight K, Rowan-Szal GA, Gray JS. Texas Christian University (TCU) short forms for assessing client needs and functioning in addiction treatment. J Offender Rehabil. 2012;51(1–2):34–56. doi: 10.1080/10509674.2012.633024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):345–70. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins KMT, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Johnson RB, Frels RK. Using debriefing interviews to promote authenticity and transparency in mixed research. Int J Mult Res Approach. 2013;7(2):271–84. [Google Scholar]

- 42.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 10 Qualitative data analysis software. 2012. Version 10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014. p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neale J, Miller P, West R. Reporting quantitative information in qualitative research: guidance for authors and reviewers. Addiction. 2014;109(2):175–6. doi: 10.1111/add.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Culbert GJ. Violence and the perceived risks of taking antiretroviral therapy in US jails and prisons. Int J Prison Health. 2014;10(1):1–17. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-05-2013-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shalihu N, Pretorius L, van Dyk A, Vander Stoep A, Hagopian A. Namibian prisoners describe barriers to HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Care. 2014;26(8):968–75. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.880398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koester KA, Morewitz M, Pearson C, Weeks J, Packard R, Estes M, et al. Patient navigation facilitates medical and social services engagement among HIV-infected individuals leaving jail and returning to the community. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(2):82–90. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Altice FL, van Hulst Y, Carbone M, Friedland GH, et al. Increasing drug users’ adherence to HIV treatment: results of a peer-driven intervention feasibility study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(2):235–46. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Unge C, Johansson A, Zachariah R, Some D, Van Engelgem I, Ekstrom AM. Reasons for unsatisfactory acceptance of antiretroviral treatment in the urban Kibera slum, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20(2):146–9. doi: 10.1080/09540120701513677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wasti SP, van Teijlingen E, Simkhada P, Randall J, Baxter S, Kirkpatrick P, et al. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Asian developing countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(1):71–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shubber Z, Calmy A, Andrieux-Meyer I, Vitoria M, Renaud-Théry F, Shaffer N, et al. Adverse events associated with nevirapine and efavirenz-based first-line antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1403–12. doi: 10.097/QAD.0b013e32835f1db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26(16):2059–67. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283578b9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Culbert GJ, Waluyo A, Iriyanti M, Muchransyah AP, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Within-prison drug injection among HIV-infected male prisoners in Indonesia: a highly constrained choice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, Swetsze C, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, et al. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(6):511–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wickersham JA, Marcus R, Kamarulzaman A, Zahari MM, Altice FL. Implementing methadone maintenance treatment in prisons in Malaysia. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(2):124–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Curran K, Ngure K, Shell-Duncan B, Vusha S, Mugo NR, Heffron R, et al. ‘If I am given antiretrovirals I will think I am nearing the grave’: kenyan HIV serodiscordant couples’ attitudes regarding early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2014;28(2):227–33. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scott-Sheldon LA, Johnson BT. Eroticizing creates safer sex: a research synthesis. J Prim Prev. 2006;27(6):619–40. doi: 10.1007/s10935-006-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.INSIGHT START Study Group. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kouyoumdjian FG, McIsaac KE, Liauw J, Green S, Karachiwalla F, Siu W, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of persons during imprisonment and in the year after release. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e13–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]