Abstract

Despite the development and wide distribution of guidelines for pneumonia, death from pneumonia is increasing due to population aging. Conventionally, aspiration pneumonia was mainly thought to be one of the infectious diseases. However, we have proven that chronic repeated aspiration of a small amount of sterile material can cause the usual type of aspiration pneumonia in mouse lung. Moreover, chronic repeated aspiration of small amounts induced chronic inflammation in both frail elderly people and mouse lung. These observations suggest the need for a paradigm shift of the treatment for pneumonia in the elderly. Since aspiration pneumonia is fundamentally based on dysphagia, we should shift the therapy for aspiration pneumonia from pathogen-oriented therapy to function-oriented therapy. Function-oriented therapy in aspiration pneumonia means therapy focusing on slowing or reversing the functional decline that occurs as part of the aging process, such as “dementia → dysphagia → dystussia → atussia → silent aspiration”. Atussia is ultimate dysfunction of cough physiology, and aspiration with atussia is called silent aspiration, which leads to the development of life-threatening aspiration pneumonia. Research pursuing effective strategies to restore function in the elderly is warranted in order to decrease pneumonia deaths in elderly people.

Keywords: Dysphagia, dystussia, aspiration pneumonia

Introduction

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the air sacs known as alveoli. Pneumonia is currently classified according to the place where the patient contract the infection, such as community-acquired pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia, and nursing home-acquired pneumonia, which is a part of health care-associated pneumonia (1-3). In each category of pneumonia, there is at least one guideline (1-6). The guidelines basically describe how to use antibiotics based on the idea that the pathogen is decided by the location. However, these guidelines do not work, at least in elderly people. Despite the wide dissemination and implementation of these guidelines, deaths from pneumonia are increasing rapidly due to population aging. Now, overtaking stroke, pneumonia is the third leading cause of death in Japan, and deaths from pneumonia occur mainly in elderly people (7).

Regardless of where they occur, most cases of pneumonia in the elderly are aspiration pneumonia, which is a function-based category of pneumonia (8). With aging, the ratio of aspiration pneumonia among cases of hospitalized pneumonia is increasing dramatically (9). Therefore, in pneumonia treatment in the elderly, we should think of the treatment for aspiration pneumonia rather than where patients are infected.

Pathogens of aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration is defined as the misdirection of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the larynx and lower respiratory tract (10). Aspiration pneumonia comprises two pathological conditions such as inflammation of the lung affecting the primarily alveoli and dysphagia-associated miss-swallowing. Different from aspiration pneumonitis, which is an acute lung injury caused by the aspiration of (usually sterile) gastric content, the usual type of aspiration pneumonia is generally recognized as a bacterial infection (11). However, physicians often experience difficulty identifying the causative bacterial pathogen in patients with aspiration pneumonia. When we examined the cultured sputum bacteria, normal flora was the most common (12). If we selected the cultured bacteria >106 cfu/mL, normal flora was still a leader, and no bacteria were detected in half of cases (12,13). The main component of normal flora is basically oral streptococci, which are pathogenic for tooth decay (12).

Recent genetic studies suggest that anaerobes and oral bacteria are detected in patients with community-acquired pneumonia more frequently than previously thought (14). These bacteria may play important roles in the development of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly. However, their prevalence is not so high, and bacterial pathogens are unclear in a large portion of aspiration pneumonia cases, suggesting the limited role of bacteria in aspiration pneumonia affecting the elderly (14,15).

Chronic inflammation in aspiration pneumonia in the elderly

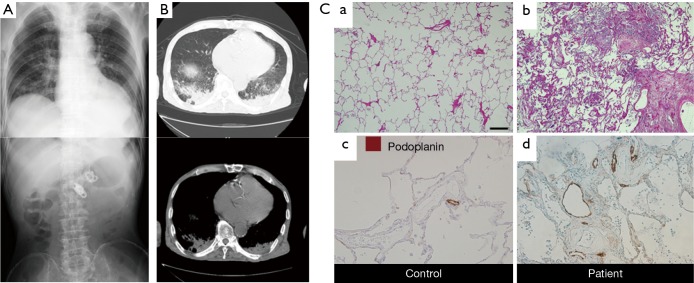

Many cases of frail elderly nursing home residents with aspiration pneumonia show sporadic fever, such as one day per week for several months, suggesting that aspiration of small amounts of not so virulent materials occur continuously once a week (16,17). In these patients (Figure 1A), chest CT shows very solid consolidation in the back (Figure 1B) (18-20). The histopathology of the consolidation shows dense infiltration of leukocytes into the alveolar spaces and alveolar walls, as well as thickened alveolar walls (20). After treatment with the lymphatic marker podoplanin, immunostaining of podoplanin showed exaggerated lymphangiogenesis on autopsy examination of the consolidation (Figure 1C). These results clearly showed the presence of chronic inflammation in the consolidation, suggesting that chronic micro-aspiration induces chronic inflammation in the lung. Matsuse et al. found a distinct entity among aspiration syndromes, named diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis (DAB), which is characterized by chronic bronchiolar inflammation due to recurrent aspiration (21). Since DAB resembles diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) radiographically and pathologically at autopsy and rarely has alveolar space infiltration with consolidation on chest X-ray, it is different from what we observed in consolidation due to chronic aspiration. Therefore, we asked the research question whether colonization of microorganisms is essential to develop chronic inflammation in the alveoli, in other words, whether aspiration of a small amount of sterile material can cause infiltration of leukocytes (20).

Figure 1.

A case of chronic micro-aspiration pneumonia. (A) Chest (upper panel) and abdominal (lower panel) X-rays of a typical case of chronic aspiration pneumonia due to repeated small amounts of aspiration. The patient was a 78-year-old male nursing home resident. He underwent percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) one year earlier and had sporadic fever one day per week for several months. At the time of admission to our geriatric unit, he had continuous low-grade fever for 5 days with coarse crackles; (B) chest CT of the same patient as in A, showing very solid consolidation in bilateral back areas; (C) chronic inflammation and exaggerated lymphangiogenesis in the lung of aspiration pneumonia patients. H&E staining of the lung from controls (a) and patients (b). Staining for lymphatics (podoplanin, brown) in controls (c) and patients (d). Control lungs have podoplanin-immunoreactive tube-like structures at low density, whereas patients’ lungs have no greater density. Scale bar: 400 µm in (a) and (b); 100 µm in (c) and (d). The data are from the same experiment as (20) but are not shown in (20).

Chronic inflammation by sterile continuous micro-aspiration

We hypothesized that chronic inflammation in lung could be induced by aspiration of oropharyngeal or gastric contents without microorganisms, such as bacteria and viruses. In order to prove this hypothesis, intranasal inoculation of a small amount of sterile oral content mix was provided to mice for 5 days a week for 28 days (20). The oral content mix comprised pepsin, lipopolysaccharide, and dextrin in PBS at pH 1.6 adjusted by HCl. Dextrin is a common reagent for thickening liquid for patients with dysphagia.

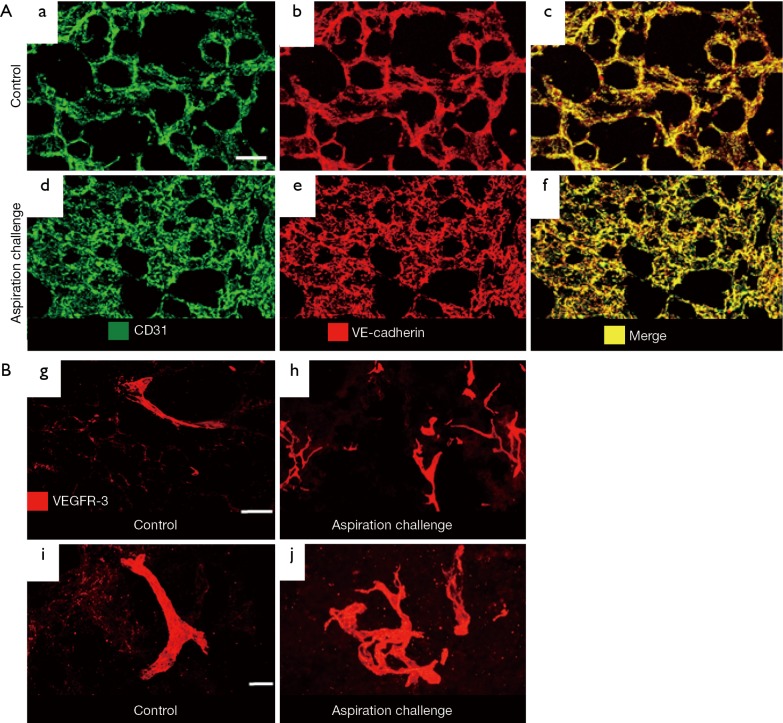

By staining blood vessels with CD31 and VE-cadherin antibodies, we observed greater blood vessel area density in the lung of the aspiration-challenged mice for 28 days (Figure 2A). By staining lymphatics with VEGF-receptor-3 antibody, we found exaggerated lymphangiogenesis in the lung of the aspiration-challenged mice for 28 days (Figure 2B). High magnification images showed a simple structure of the lymphatics in the controls and a complex structure of the lymphatics in the aspiration group. Thus, we found that mouse lung after 28 days of chronic micro-aspiration showed chronic inflammation accompanied by both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (20).

Figure 2.

A mouse model of chronic micro-aspiration. (A) Greater blood vessel area density in the lung of the aspiration-challenged mice for 28 days. Staining for blood vessels (CD31 in green and VE-cadherin in red) in the control (a-c) and 28-day aspiration-challenged mice (d-f). Scale bar: 50 µm. (B) Exaggerated lymphangiogenesis in the lung of the aspiration-challenged mice for 28 days. Staining for lymphatics (VEGFR-3, red) in the control (g and i) and 28-day aspiration-challenged mice (h and j). Lymphatics in the control group (g and i) are distributed sparsely, whereas those in the aspiration group (h and j) are distributed densely. High-magnification images show a simple structure of lymphatics in the controls and a complex structure of lymphatics in the aspiration group. Scale bar: 100 µm in (g) and (h); 20 µm in (i) and (j). The data are from the same experiments (20) but not shown in (20).

This observation indicated that it is not necessary to have micro-organisms in order to develop the chronic type of aspiration pneumonia. Many chronic types of aspiration pneumonia may not be an infectious disease but a chemical pneumonitis with chronic inflammation. However, the pneumonitis differs from aspiration pneumonitis defined by Marik (11), which is an acute lung injury after the inhalation of regurgitated gastric contents.

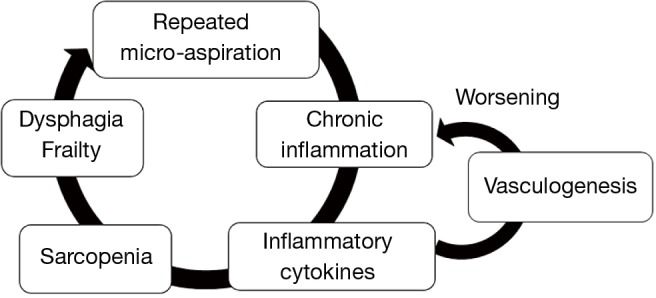

Vicious cycle of aspiration pneumonia due to chronic micro-aspiration

Chronic micro-aspiration induced chronic inflammation in the lung, which caused both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Inflammatory cells secrete many angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors, including VEGF families, TNFα, and other cytokines (22,23). Multiple types of leukocytes and macrophages contribute to proteolytic remodeling of the extracellular matrix (24,25). Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis facilitate additional recruitment of immune cells, resulting in enhancement of chronic inflammation (23,25,26).

On the other hand, elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 induce a decrease in muscle mass and strength, called sarcopenia (27-30). Sarcopenia plays a key role in the development of frailty in the elderly (27,30). In particular, sarcopenia of swallowing muscles is directly associated with oral frailty and dysphagia (31), leading to a vicious cycle of chronic aspiration (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Vicious cycle of chronic aspiration pneumonia due to repeated small amounts of aspiration.

Since the vicious cycle could occur without involvement of virulent microorganisms, we should consider how to prevent aspiration, rather than how to use antibiotics in elderly patients with pneumonia.

Dysphagia, dystussia, and aspiration pneumonia

The recent large-scale cross-sectional study in Japanese elderly people showed that the risk factors for aspiration pneumonia were sputum suctioning, dysphagia, dehydration, and dementia (32). The incidence rate for dementia increased exponentially with age, with the most notable rise occurring through the seventh and eighth decades of life (33). A recent study has shown that patients with senile dementia inevitably develop dysphagia and have a high risk of death due to pneumonia from aspiration (34). Although repeated aspiration occurs due to dysphagia, pneumonia rarely develops if the aspirated material is completely expelled from the airway by cough (35). Therefore, both dysphagia and dystussia, which is an impaired cough response, are important elements for developing aspiration pneumonia.

It is noteworthy that dysphagia and dystussia usually do not occur simultaneously in elderly people. Nakajoh et al. investigated the distribution of both swallowing and cough reflex sensitivities in nursing home residents (35). They showed that there are residents whose swallowing reflex is impaired, but their cough reflex is maintained, whereas there are few residents whose swallowing reflex is intact and cough reflex is impaired (35). The results suggest that dystussia occurs subsequent to dysphagia in nursing-home residents. Similarly, patients with neurogenic dysphagia, including patients with Parkinson’s disease, did not have reduced cough reflex sensitivity, suggesting that impairment of the swallowing reflex was followed by impairment of the cough reflex in the majority of the elderly (36).

Mitchell et al. reported that, in patients with advanced dementia who were institutionalized in a nursing home, there was about a 300-day time-lag between the start of an eating problem and suffering from life-threatening pneumonia (37). Considering that pneumonia is the consequence of combined impairment of swallowing and coughing functions, the study also suggests that dystussia follows dysphagia in elderly persons with dementia.

Atussia and silent aspiration in aging

Although impaired cough has been observed in patients with repeated aspiration pneumonia (38,39), evaluations of age-related changes of cough reflex sensitivity did not show a significant decrease not only in elderly people who led active daily lives (40), but also in demented frail elderly without a history of aspiration pneumonia (41). However, we found that the perception of the urge-to-cough decreased with aging despite no change of the cough reflex threshold in elderly people without aspiration pneumonia (41). Notably, in elderly frail people with a history of repeated aspiration pneumonia, they hardly perceived the urge-to-cough, even with the strongest stimuli (42). Such elderly people were revealed to have almost no response to tussive stimuli (38,42). An inability to cough with tussive stimuli is called atussia, which is the ultimate dysfunction of cough physiology, and aspiration with atussia is called silent aspiration (43).

Dysfunction of both neuronal and motor components of coughing causes atussia. However, the decreased perception of the urge-to-cough suggests impairment of the neuronal component rather than the motor component in elderly people (41). Recently, accumulating evidence indicates that dysfunction of cough physiology could be due to the disruption of both the cortical pathway for cough and the medullary reflex pathway (44). The urge-to-cough is a brain component of the cough motivation-to-action system (45). Therefore, decreased urge-to-cough sensitivity suggests impairment of the cortical system of neuronal control of coughing physiology.

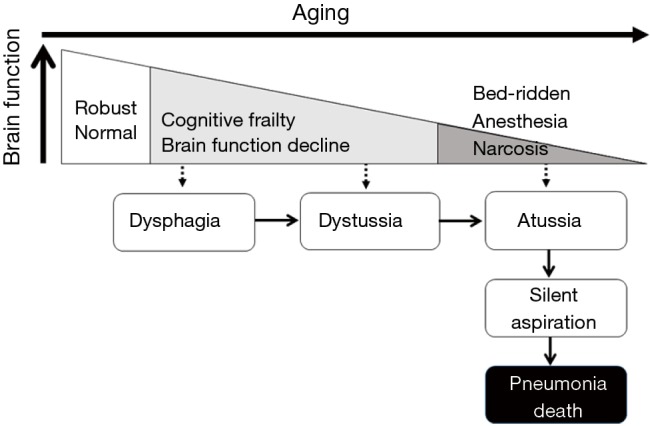

Aging is associated with a decline in brain function across multiple domains, including cognitive and emotional processes (46,47), which are related to brain pathologies such as atrophy, cerebrovascular diseases, degenerative diseases, and circuit pathologies (47,48). We show the natural course of humans with declining brain function in Figure 4. With aging, brain function starts to decline. Dysphagia may occur in the earlier stages of brain dysfunction. Then, with progression of brain dysfunction, dystussia may occur. Then, at the almost terminal stages of brain dysfunction, people suffer from atussia, resulting in silent aspiration, which is related to death from pneumonia (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The natural course of functional decline in most elderly people. With aging, brain function declines. With declining brain function, dysphagia starts, followed by dystussia, and then finally atussia and silent aspiration, which is closely related to death from pneumonia.

Paradigm shift for pneumonia treatment in elderly people

The entire description above suggests the need for a paradigm shift of the treatment of pneumonia in the elderly. First, we should recognize that pneumonia in the elderly is sometimes chronic inflammation rather than acute inflammation. Second, we should recognize that aspiration pneumonia is sometimes sterile chemical inflammation rather than bacterial infection. Since aspiration pneumonia is fundamentally based on dysphagia (49), we should shift the therapy for aspiration pneumonia from pathogen-oriented therapy to function-oriented therapy.

Function-oriented therapy in aspiration pneumonia means therapy focusing on reversal of the functional decline that occurs in the aging process, such as “dementia → dysphagia → dystussia → atussia → silent aspiration”. Recently, strategies to treat dysphagia have been extensively investigated (50,51). Since the methodologies to restore either dystussia or atussia are seriously limited, researchers should focus on how to improve coughing dysfunction rather than the development of new antibiotics in order to decrease mortality due to pneumonia in elderly people.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (Grant numbers 24300187, 24659397, 26460899, 15K12588, 15K15254), and Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (25-7) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Niederman MS, Bass JB, Jr, Campbell GD, et al. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. American Thoracic Society. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:1418-26. 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventive strategies. A consensus statement, American Thoracic Society, November 1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1711-25. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America . Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:388-416. 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The committee for the Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines in management of respiratory infections (2006). The Japanese Respiratory Society guideline for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Respirology 2006;11:S1-S77.16423260 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The committee for the Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines in management of respiratory infections (2009). The Japanese Respiratory Society guideline for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults. Respirology 2008;14:S1-S71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohno S, Imamura Y, Shindo Y, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for nursing- and healthcare-associated pneumonia (NHCAP) [complete translation]. Respir Investig 2013;51:103-26. 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Handbook of Health and Welfare Statistics 2014 Contents. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hh/1-2.html

- 8.Teramoto S, Yoshida K, Hizawa N. Update on the pathogenesis and management of pneumonia in the elderly-roles of aspiration pneumonia. Respir Investig 2015;53:178-84. 10.1016/j.resinv.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teramoto S, Fukuchi Y, Sasaki H, et al. High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:577-9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marik PE, Kaplan D. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest 2003;124:328-36. 10.1378/chest.124.1.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2001;344:665-71. 10.1056/NEJM200103013440908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamanda S, Ebihara S, Ebihara T, et al. Bacteriology of aspiration pneumonia due to delayed triggering of the swallowing reflex in elderly patients. J Hosp Infect 2010;74:399-401. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebihara S, Kohzuki M, Sumi Y, et al. Sensory stimulation to improve swallowing reflex and prevent aspiration pneumonia in elderly dysphagic people. J Pharmacol Sci 2011;115:99-104. 10.1254/jphs.10R05CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki K, Kawanami T, Yatera K, et al. Significance of anaerobes and oral bacteria in community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One 2013;8:e63103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi S, Mukae H, Kawanami T, et al. Bacteriological assessment of healthcare-associated pneumonia using a clone library analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124697. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meguro K, Yamagauchi S, Doi C, et al. Prevention of respiratory infections in elderly bed-bound nursing home patients. Tohoku J Exp Med 1992;167:135-42. 10.1620/tjem.167.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu X, Lee JS, Pianosi PT, et al. Aspiration-related pulmonary syndromes. Chest 2015;147:815-23. 10.1378/chest.14-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komiya K, Ishii H, Umeki K, et al. Computed tomography findings of aspiration pneumonia in 53 patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:580-5. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prather AD, Smith TR, Poletto DM, et al. Aspiration-related lung diseases. J Thorac Imaging 2014;29:304-9. 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nihei M, Okazaki T, Ebihara S, et al. Chronic inflammation, lymphangiogenesis, and effect of an anti-VEGFR therapy in a mouse model and in human patients with aspiration pneumonia. J Pathol 2015;235:632-45. 10.1002/path.4473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuse T, Oka T, Kida K, et al. Importance of diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis caused by chronic occult aspiration in the elderly. Chest 1996;110:1289-93. 10.1378/chest.110.5.1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010;140:883-99. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa C, Incio J, Soares R. Angiogenesis and chronic inflammation: cause or consequence? Angiogenesis 2007;10:149-66. 10.1007/s10456-007-9074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rüegg C. Leukocytes, inflammation, and angiogenesis in cancer: fatal attractions. J Leukoc Biol 2006;80:682-4. 10.1189/jlb.0606394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YW, West XZ, Byzova TV. Inflammation and oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:323-8. 10.1007/s00109-013-1007-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan KW, Chong SZ, Angeli V. Inflammatory lymphangiogenesis: cellular mediators and functional implications. Angiogenesis 2014;17:373-81. 10.1007/s10456-014-9419-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drey M. Sarcopenia - pathophysiology and clinical relevance. Wien Med Wochenschr 2011;161:402-8. 10.1007/s10354-011-0002-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:877-82. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki T, Liang F, Li T, et al. Muscle-specific inhibition of the classical nuclear factor-κB pathway is protective against diaphragmatic weakness in murine endotoxemia. Crit Care Med 2014;42:e501-9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowen TS, Schuler G, Adams V. Skeletal muscle wasting in cachexia and sarcopenia: molecular pathophysiology and impact of exercise training. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015;6:197-207. 10.1002/jcsm.12043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda K, Akagi J. Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor of dysphagia in hospitalized older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/ggi.12486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manabe T, Teramoto S, Tamiya N, et al. Risk Factors for Aspiration Pneumonia in Older Adults. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140060. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;7:137-52. 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosch X, Formiga F, Cuerpo S, et al. Aspiration pneumonia in old patients with dementia. Prognostic factors of mortality. Eur J Intern Med 2012;23:720-6. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakajoh K, Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, et al. Relation between incidence of pneumonia and protective reflexes in post-stroke patients with oral or tube feeding. J Intern Med 2000;247:39-42. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith PE, Wiles CM. Cough responsiveness in neurogenic dysphagia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;64:385-8. 10.1136/jnnp.64.3.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529-38. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekizawa K, Ujiie Y, Itabashi S, et al. Lack of cough reflex in aspiration pneumonia. Lancet 1990;335:1228-9. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92758-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakazawa H, Sekizawa K, Ujiie Y, et al. Risk of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly. Chest 1993;103:1636-7. 10.1378/chest.103.5.1636b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katsumata U, Sekizawa K, Ebihara T, et al. Aging effects on cough reflex. Chest 1995;107:290-1. 10.1378/chest.107.1.290-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebihara S, Ebihara T, Kanezaki M, et al. Aging deteriorated perception of urge-to-cough without changing cough reflex threshold to citric acid in female never-smokers. Cough 2011;7:3. 10.1186/1745-9974-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamanda S, Ebihara S, Ebihara T, et al. Impaired urge-to-cough in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia. Cough 2008;4:11. 10.1186/1745-9974-4-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolser DC. Pharmacologic management of cough. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010;43:147-55, xi. 10.1016/j.otc.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet 2008;371:1364-74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davenport PW. Urge-to-cough: what can it teach us about cough? Lung 2008;186 Suppl 1:S107-11. 10.1007/s00408-007-9045-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buckner RL. Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron 2004;44:195-208. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brodaty H, Altendorf A, Withall A, et al. Do people become more apathetic as they grow older? A longitudinal study in healthy individuals. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:426-36. 10.1017/S1041610209991335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao H, Takashima Y, Mori T, et al. Hypertension and white matter lesions are independently associated with apathetic behavior in healthy elderly subjects: the Sefuri brain MRI study. Hypertens Res 2009;32:586-90. 10.1038/hr.2009.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: current reality and scope of the problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:259-70. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ebihara S, Ebihara T, Gui P, et al. Thermal taste and anti-aspiration drugs: a novel drug discovery against pneumonia. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:2755-9. 10.2174/13816128113199990567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Pede C, Mantovani ME, Del Felice A, et al. Dysphagia in the elderly: focus on rehabilitation strategies. Aging Clin Exp Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s40520-015-0481-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]