Main Text

Cardiac myocytes derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (h-iPSCs) are an exciting novel human experimental system that has great promise for use in cardiac drug safety design, testing, and research. Despite the very recent emergence of this technology (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), the use of iPSC-derived (iPSCD) cardiocytes in research and drug development has exploded (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). Development of safety testing approaches using iPSCD cardiocytes is actively encouraged by the both the FDA (20) and the international consortium that regulates drug safety standards in their recent comprehensive in vitro proarrhythmia assay initiative. Because of the known and suspected limitations in the iPSCD cardiocytes and interpretation of iPSCD cardiocytes data, the comprehensive in vitro proarrhythmia assay initiative states that experimentation on iPSCD cardiocytes should be combined with in silico approaches (20). Considerable debate on what the limitations of this new preparation are, and how to extract the most useful information from it, has been generated. The original Biophysical Letter of Du et al. (21) and the correspondence between Giles and Noble (22) and Kane et al. (23) are an example of this debate.

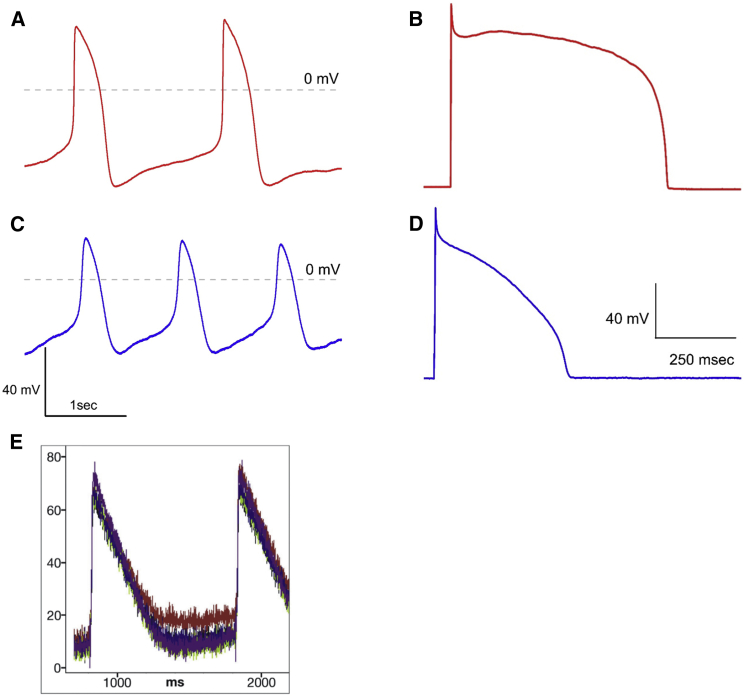

h-iPSCD cells are used in a variety of preparations and measured using a variety of techniques. The technique of electronic expression of IK1 by Bett et al. (8) as employed by our group to distinguish between cell types was discussed extensively in the correspondence between Giles and Noble (22) and Kane et al. (23). The method of Bett et al. (8) uses a dynamic clamp to insert a computer-generated IK1 into single iPSCD myocytes. As shown in Fig. 1, this changes the action potential morphology considerably from the spontaneously active case and clearly shows cells with atrial-like and ventricular-like types of action potentials. In contrast, Du et al. (21) used a voltage-sensitive dye, in the presence of blebbistatin, to measure the action potential (shown for comparison in Fig. 1 E) in monolayers. The dye measurements of Du et al. (21) somewhat resemble the spontaneous APs recorded under voltage-clamp, but may also reflect some of the limitations of optical measurements of membrane potential. Even minor photodynamic damage associated with Di-8-ANEPPS tends to increase linear background currents that may alter the action potential and change the morphology of both atrial and ventricular myocytes; clearly, the action potentials are more triangular than those measured using other methods (24, 25). It is unclear from their example if the methods employed by Du et al. (21) are influencing their ability to clearly distinguish cell type through action potential morphology. Other less damaging and invasive methods can potentially give more detailed information on action potential shape in iPSCD myocytes (24, 25). We agree with the observation of Kane et al. (23) that more studies are needed “involving genetically encoded or more quantitative and less toxic ratiometric dyes”.

Figure 1.

Action potential morphology. (A) Spontaneous action potentials from ventricular type h-iPSCD cardiac cell recorded using the patch-clamp technique. (B) Stimulated action potentials from the same cell with electronic expression of IK1. (C) Spontaneous action potentials from an atrial type h-iPSCD cardiac cell recorded using the patch-clamp technique. (D) Stimulated action potentials from the same cell with electronic expression of IK1. (E) Representative monolayer action potentials recorded using optical techniques from the article of Du et al. (21).

Careful scrutiny of data is always important and we read with great interest the reanalysis of one of the figures looking at the distribution of cell types within the correspondence of Kane et al. (23). Fig. 1 B from Kane et al. (23) shows a fit of a hyperbolic equation designed to pass through our data, which Kane et al. (23) suggests is indicative of a potentially continuous distribution of cell types. Our interpretation is very different. We view the need to use such a sharply curved line in this fit showing that we have indeed two separated two distinct populations. This is further reinforced by the rather poor fit of the curve to the ventricular-like cell data. At the inflection point, there may indeed be some overlap in AP characteristics between types. In years of working with acutely isolated adult myocytes, it is clear that even for freshly isolated adult heart myocytes there is a significant overlap in shape between ventricular and atrial cells.

In their reanalysis of our data, Kane et al. (23) comment heavily on variability and “argue that action potential duration is fairly homogeneously distributed, even after corrections for IK1”. We appreciate the chance to comment directly on this misconception about the data in the article of Bett et al. (8). In Bett et al. (8), we used a single magnitude and representation of IK1 for every cell. IK1 was not cell-specific, and was not matched to cell type or capacitance. The result is that for ventricular-like cells, a very low IK1 current density was used relative to that found physiologically in adult ventricular myocytes. Conversely, a somewhat high density was used for atrial-like cells. This is due both to the larger capacitance of the ventricular-like types and the much higher IK1 density in adult ventricular cells relative to adult atrial myocytes. This explains why, under the conditions of Bett et al. (8), ventricular-like cells have durations of >1 s. Lack of cell-specific tuning of IK1 also explains a large portion of the cell variability in the article of Bett et al. (8). Both adult cardiac ventricular myocytes as well as iPSCD cells vary significantly in capacitance. Because a one-size-fits-all approach was used in that article, the current density (in pA/pFd) of IK1 also varied accordingly and AP duration is strongly and nonlinearly sensitive to IK1 density (26, 27, 28). In future studies looking at cell physiology, it will be useful to normalize the magnitude of electronic expression of IK1 to provide a uniform current density rather than an identical per cell current. In this study, the analysis of Kane et al. (23) is inappropriate.

Kane et al. (23) also transformed data from Bett et al. (8), as shown in Fig. 1 D. They assert that these data do “not cluster into two subpopulations and there is no relationship between this distribution and the ventricular label assigned in Fig. 1 A”. We disagree; a preliminary cluster analysis of our data using a K-means test (29) for K = 2 suggests two separate groups, portioning roughly along the lines of our criterion and with a p < 0.001 of being random. The difference between APD30 and APD90 covers a range where IK1 is more active than at the plateau. Therefore, the absolute magnitude of APD30-APD90 is an inappropriate measure of action potential shape differences and is a misinterpretation of the data from the article of Bett et al. (8). The data transformation of Kane et al. (23) in Fig. 1 D still shows clear separation of components. Essentially, all of the ventricular-like points lie above the atrial-like points on this x,y plot. This difference clearly shows that there is indeed a shape difference and that this occurs in early repolarization, where synthetic IK1 is relatively unimportant.

Human iPSCD cardiocyte technology is only a few years old and being explored in many directions, using many approaches. Very basic questions are being addressed, including: do chamber-specific cell types exist in cultured iPSCD cardiocyte preparations? Can they be identified quickly? How can they be identified? These are very important questions, and will not be answered in a single article. We agree with both groups that more experimental evidence to support the idea that iPSC-CMs spontaneously form distinct, chamber-specific subtypes is needed. Bett et al. (8) shows that in the presence of electronic expression of IK1, action potentials can be separated into distinct populations and that the morphology of these action potentials is consistent with an atrium versus ventricle distinction. The next step is to demonstrate that this sorting based on morphology provides consistent data with other chamber-specific cellular properties. Preliminary data from our laboratory (30) presented in abstract form at this year’s Biophysical Society Meeting suggests that this is the case; distinct action potential morphologies have underlying channel current properties consistent with an atrial versus ventricle phenotype.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grant Nos. HL093631 and HL127901 to G.C.L.B., and HL062465 and HL088058 to R.L.R.; American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid No. 12GRNT9120014 to R.L.R.; and an award from the State University of New York Technology Accelerator Fund to G.C.L.B.

Editor: Godfrey Smith.

Contributor Information

Glenna C.L. Bett, Email: bett@buffalo.edu.

Randall L. Rasmusson, Email: rr32@buffalo.edu.

References

- 1.Itzhaki I., Maizels L., Gepstein L. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narazaki G., Uosaki H., Yamashita J.K. Directed and systematic differentiation of cardiovascular cells from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2008;118:498–506. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuzmenkin A., Liang H., Hescheler J. Functional characterization of cardiomyocytes derived from murine induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro. FASEB J. 2009;23:4168–4180. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moretti A., Bellin M., Laugwitz K.L. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J., Verma P.J., Pebay A. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from Friedreich ataxia patients. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;7:703–713. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gai H., Leung E.L., Ma Y. Generation and characterization of functional cardiomyocytes using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human fibroblasts. Cell Biol. Int. 2009;33:1184–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T., Tohyama S., Fukuda K. In vitro pharmacologic testing using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;385:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bett G.C., Kaplan A.D., Rasmusson R.L. Electronic “expression” of the inward rectifier in cardiocytes derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1903–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh A., Patel D., Salama G. Relaxin suppresses atrial fibrillation by reversing fibrosis and myocyte hypertrophy and increasing conduction velocity and sodium current in spontaneously hypertensive rat hearts. Circ. Res. 2013;113:313–321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knollmann B.C. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: boutique science or valuable arrhythmia model? Circ. Res. 2013;112:969–976. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinnecker D., Goedel A., Moretti A. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: a versatile tool for arrhythmia research. Circ. Res. 2013;112:961–968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Condorelli G. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in studies of inherited arrhythmias. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:84–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI62838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott G.W. KCNE genetics and pharmacogenomics in cardiac arrhythmias: much ado about nothing? Expert Rev. Clinical Pharmacol. 2013;6:49–60. doi: 10.1586/ecp.12.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrichs S., Malan D., Sasse P. Modeling long QT syndromes using induced pluripotent stem cells: current progress and future challenges. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2013;23:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraushaar U., Meyer T., Guenther E. Cardiac safety pharmacology: from human Ether-á-gogo related gene channel block towards induced pluripotent stem cell based disease models. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2012;11:285–298. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.639358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu T.Y., Yang L. Uses of cardiomyocytes generated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Therapy. 2011;2:44. doi: 10.1186/scrt85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang P., Lan F., Wu J.C. Drug screening using a library of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes reveals disease-specific patterns of cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2013;127:1677–1691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson J.K., Yue Y., Numann R. Human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes detect drug-mediated changes in action potentials and ion currents. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2014;70:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozaki Y., Honda Y., Funabashi H. Availability of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in assessment of drug potential for QT prolongation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014;278:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sager P.T., Gintant G., Stockbridge N. Rechanneling the cardiac proarrhythmia safety paradigm: a meeting report from the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Am. Heart J. 2014;167:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du D.T., Hellen N., Terracciano C.M. Action potential morphology of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes does not predict cardiac chamber specificity and is dependent on cell density. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giles W.R., Noble D. Rigorous Phenotyping of Cardiac iPSC Preparations Requires Knowledge of Their Resting Potential(s) Biophys. J. 2016;110:278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane C., Du D.T.M., Hellen N., Terracino C.M. The fallacy of assigning chamber specificity to iPSC cardiac myocytes from action potential morphology. Biophys. J. 2016;110:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinnawi R., Huber I., Gepstein L. Monitoring human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes with genetically encoded calcium and voltage fluorescent reporters. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;5:582–596. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J.J., Yang L., Salama G. Mechanism of automaticity in cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015;81:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordeiro J.M., Zeina T., Panama B.K. Regional variation of the inwardly rectifying potassium current in the canine heart and the contributions to differences in action potential repolarization. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015;84:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieu D.K., Fu J.D., Li R.A. Mechanism-based facilitated maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2013;6:191–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.973420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meijer van Putten R.M., Mengarelli I., Wilders R. Ion channelopathies in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes: a dynamic clamp study with virtual IK1. Front. Physiol. 2015;6:7. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remm K., Kelviste T. An online calculator for spatial data and its applications. Comput. Ecol. Softw. 2014;4:22–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan A.D., Bett G.C.L., Rasmusson R.L. Electronic expression of IK1 in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiocytes reveals atrial versus ventricular specific properties. Biophys. J. 2015;108:112a. [Google Scholar]