Abstract

AIM: To evaluate whether Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy benefits patients with functional dyspepsia (FD).

METHODS: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the efficacy and safety of H. pylori eradication therapy for patients with functional dyspepsia published in English (up to May 2015) were identified by searching PubMed, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library. Pooled estimates were measured using the fixed or random effect model. Overall effect was expressed as a pooled risk ratio (RR) or a standard mean difference (SMD). All data were analyzed with Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 12.0.

RESULTS: This systematic review included 25 RCTs with a total of 5555 patients with FD. Twenty-three of these studies were used to evaluate the benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy for symptom improvement; the pooled RR was 1.23 (95%CI: 1.12-1.36, P < 0.0001). H. pylori eradication therapy demonstrated symptom improvement during long-term follow-up at ≥ 1 year (RR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.12-1.37, P < 0.0001) but not during short-term follow-up at < 1 year (RR = 1.26; 95%CI: 0.83-1.92, P = 0.27). Seven studies showed no benefit of H. pylori eradication therapy on quality of life with an SMD of -0.01 (95%CI: -0.11 to 0.08, P = 0.80). Six studies demonstrated that H. pylori eradication therapy reduced the development of peptic ulcer disease compared to no eradication therapy (RR = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.18-0.68, P = 0.002). Eight studies showed that H. pylori eradication therapy increased the likelihood of treatment-related side effects compared to no eradication therapy (RR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.12-3.65, P = 0.02). Ten studies demonstrated that patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy were more likely to obtain histologic resolution of chronic gastritis compared to those who did not receive eradication therapy (RR = 7.13; 95%CI: 3.68-13.81, P < 0.00001).

CONCLUSION: The decision to eradicate H. pylori in patients with functional dyspepsia requires individual assessment.

Keywords: Functional dyspepsia, Helicobacter pylori eradication, Symptom improvement, Quality of life, Peptic ulceration, Meta-analysis

Core tip: The decision to eradicate Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in patients with functional dyspepsia requires individual assessment. This meta-analysis suggests that H. pylori eradication therapy is beneficial for symptom relief, reduces the development of peptic ulceration, and leads to histologic resolution of chronic gastritis but does not improve the quality of life and may even result in adverse events. Otherwise, other validated treatment such as acid suppression, prokinetics, and psychiatric treatment should also be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder and affects as many as 21%[1] of the population worldwide and 2%-24%[2,3] of the Chinese population. Characterized by epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, and early satiation without organic causes, FD adversely impacts the patient’s quality of life. FD is diagnosed by Rome III criteria, which are symptom-based criteria[4]. Although the pathophysiology is not well established, gastro-duodenal motility dysfunction[5,6], visceral hypersensitivity[7,8], and psychological disturbance[9] may play a role in the pathogenesis of FD. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is more common in patients with dyspepsia (OR = 2.3; 95%CI: 1.9-2.7) in comparison to healthy controls[10]. However, the effects of H. pylori eradication therapy in FD are inconsistent in previously published randomized trials and meta-analyses.

Previous meta-analyses mainly focused on symptom improvement after H. pylori eradication therapy; their findings (whether or not to eradicate) were not consistent because of variable study designs and follow-up durations[11-13]. One meta-analysis conducted by Moayyedi et al[14] provided an economic evaluation and suggested that H. pylori eradication therapy is the most cost-effective treatment method. We carried out this meta-analysis not only to evaluate benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy for symptom relief, but also to discuss the effects on the quality of life, adverse events, and the risk of subsequent peptic ulcer disease. We performed a more comprehensive meta-analysis than previous studies in order to assess the overall clinical impact of H. pylori eradication therapy in this population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A standard protocol, based on current PRISMA guidelines, was implemented for study inclusion, data extraction, and data analysis. PubMed, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library were searched for published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in English from 1988 to 2015. The main search strategies were as follows: “Helicobacter pylori OR Campylobacter OR Campylobacter pylori OR C. pylori OR Helicobacter infection” AND “treat OR eradication OR eradicating OR therapy OR anti-“ AND “dyspepsia OR functional gastrointestinal disorder OR non-ulcer dyspepsia OR functional dyspepsia.”

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) RCTs; (2) study population of patients with dyspepsia (symptom-based criteria including ROME I, II, or III) and H. pylori infection (13C breath test, histology, or rapid urease teat); (3) H. pylori eradication regimens (dual, triple, quadruple, and sequential therapies) as intervention for treatment group and placebo or other drugs known not to eradicate H. pylori (no antibiotics or bismuth) as intervention for control groups; and (4) age above 17 years old. Studies were excluded if they were available only as abstracts, review studies, case reports, or if predefined outcome data required for analyses were lacking.

Data extraction and quality evaluation

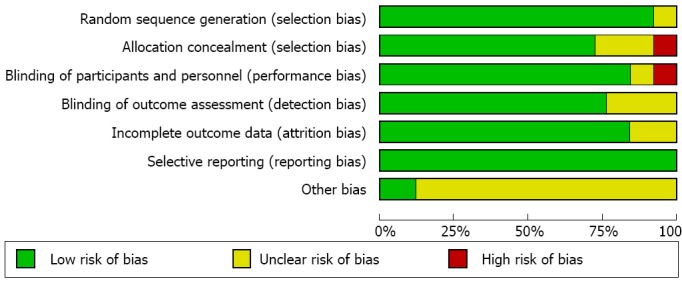

Two investigators (Du LJ, Chen BR) reviewed all the titles and abstracts independently. Data was extracted from eligible full-text studies. The data included study population, demographical characteristics, year of publication, country, age, gender, H. pylori eradication regimens, duration of follow-up, H. pylori eradication rate, and study outcomes. The individual study quality was assessed according to the Cochrane collaboration’s tool for risk of bias, which contains random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blindness, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases. Any disagreement was resolved by a third investigator (Dai N).

Study endpoints

The primary outcome for this study was the pooled risk ratio (RR) of successful treatment (presence of no more than mild pain or discomfort after treatment) with a 95%CI. The secondary outcomes were the pooled RR of improvement of dyspepsia at short-term (< 1 year) and long-term (≥ 1 year) follow-up, standard mean difference (SMD) of improvement in quality of life (SF-36), pooled RR of incidence of peptic ulceration during follow-up, pooled RR of development of treatment-related adverse events, and pooled RR of histologic resolution of chronic gastritis. If the studies were homogeneous (I2 < 50%), the fixed-effects model was used; otherwise (I2 > 50%), the random-effects model was chosen. Intervention was considered statistically significant when a P-value was < 0.05. If the studies were heterogeneous, a sensitivity analysis was performed. Publication bias was assessed by the funnel plot. All data were analyzed with RevMan 5.3 and Stata 12.0. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by professor Yun-Xian Yu from Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics of Zhejiang University.

RESULTS

Literature search and description of included studies

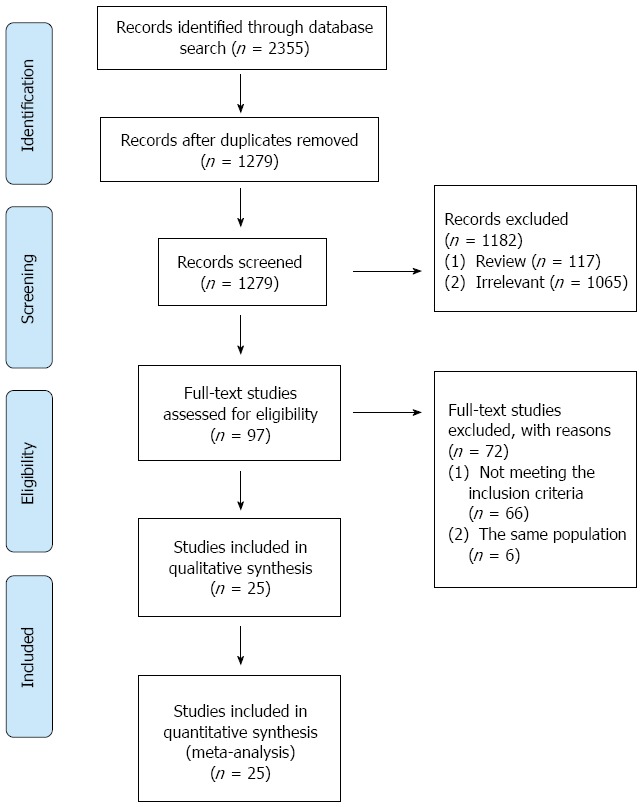

According to the search strategy, 2355 citations were identified from three databases. After removing the duplicates (n = 1076), two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant studies (n = 1279) independently. Out of 97 full-text studies that were reviewed, 66 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twenty-five RCTs with a total of 5555 people Which met the inclusion criteria were included in this systematic review (Figure 1)[15-39]. The assessment on the quality of the individual study is shown in Figure 2. The demographic data, eradication regimens, and eradication rates are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool was used to evaluate risk of bias.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Sample (M/F) | Age, mean | Country | Last visit (mo) | Intervention | Helicobacter pylori eradication |

| Ang, 2006 | 130 (47/83) | 38.0 | Singapore | 12 | LAC | 73.2% |

| Blum, 1998 | 328 (136/192) | 47.0 | Global | 12 | OAC | 79% |

| Chiba, 2002 | 394 (148/246) | 49.5 | Canada | 12 | OMC | 75% |

| Dhali, 1999 | 62 (44/18) | 32.5 | India | 12 | BMTe | 87.5% |

| Froehlich, 2001 | 144 (64/80) | 44.6 | Switzerland | 12 | LAC | 75% |

| Gisbert, 2004 | 50 (15/35) | 41.5 | Spain | 12 | OAC | 76% |

| Greenberg, 1999 | 100 (31/69) | 46.5 | United States | 12 | OC | 70.5% |

| Gwee, 2009 | 82 (38/44) | 40.4 | Singapore | 12 | OCT | 68.3% |

| Hsu, 2001 | 161 (78/83) | 50.9 | China | 12 | LMTe | 78% |

| Koelz, 2003 | 181 (74/107) | 47.5 | Switzerland | 6 | AO | 51.7% |

| Koskenpato, 2001 | 151 (52/99) | 51.7 | Finland | 12 | AMO | 82% |

| Lan, 2011 | 195 (89/106) | 47.4 | China | 3 | RAC | 85.7% |

| Malfertheiner, 2003 | 800 (380/420) | 46.2 | Germany | 12 | LAC | 63.9% |

| Mazzoleni, 2006 | 89 (20/69) | 41.3 | Brazil | 12 | LAC | 91.3% |

| Mazzoleni, 2011 | 404 (86/318) | 46.0 | Brazil | 12 | OAC | 88.6% |

| McColl, 1998 | 318 (155/163) | 42.1 | United Kingdom | 12 | AMO | 88% |

| Miwa, 2000 | 85 (40/45) | 51.5 | Japan | 3 | OAC | 85.4% |

| Naeeni, 2002 | 157 (47/110) | 32.5 | Iran | 9 | ABM | 52.6% |

| Sodhi, 2013 | 519 (169/350) | 44.5 | India | 12 | OAC | 69.9% |

| Talley, 1999 | 293 (133/160) | 46.4 | United States | 12 | LCA | 80% |

| Talley, 1999 (ORCHID) | 275 (98/177) | 50.0 | Australia | 12 | OAC | 85% |

| Varannes, 2001 | 253 (112/141) | 51.0 | France | 12 | RaAC | 69% |

| Varasa, 2008 | 48 (21/27) | 37.0 | Spain | 12 | RA | 81.4% |

| Xu, 2013 | 396 (135/261) | 40.0 | China | 12 | ACE | 76.36% |

| Zanten, 2003 | 157 (72/81) | 48.0 | Canada | 12 | LCA | 82% |

M/F: Male/female; A: Amoxillin; B: Bismuth salt; C: Clarithromycin; E: Esoprazole; F: Furazolidone; L: Lansoprazole; M: Metronidizole; O: Omeprazole; R: Rabeprazole; Ra: Ranitidine; T: Tinidazole; Te: Tetracycline.

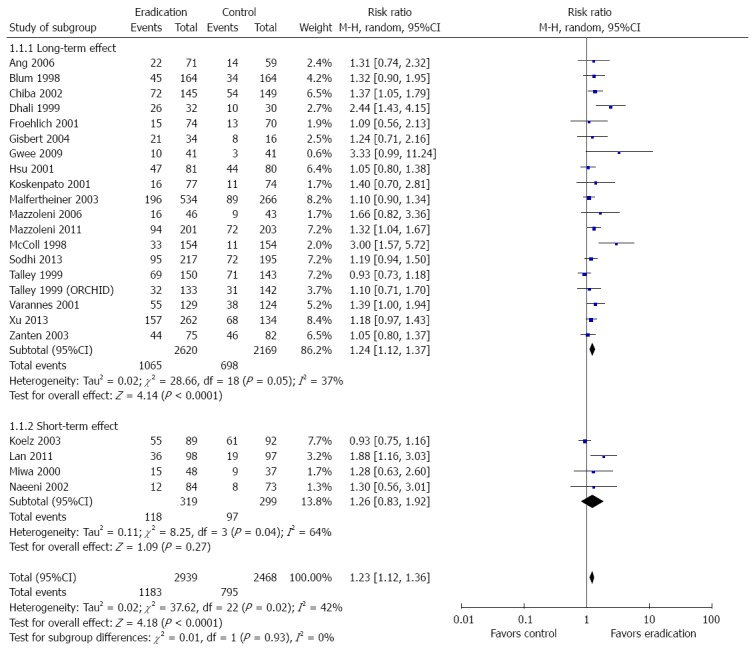

Benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy on symptom improvement

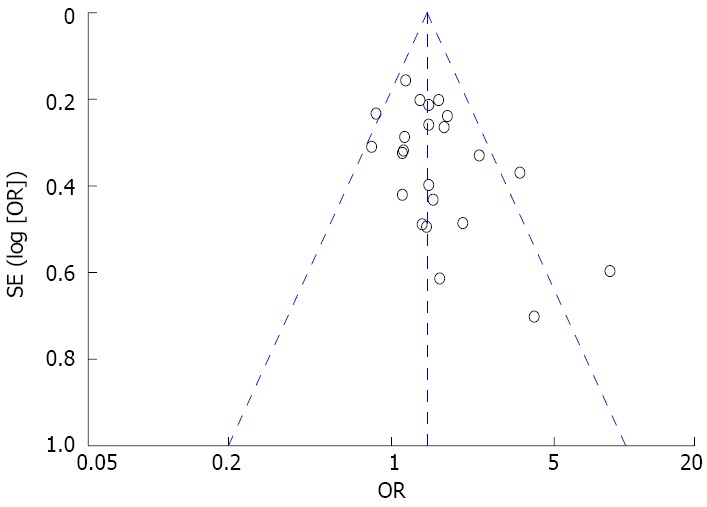

Twenty-three of 25 studies reported information on treatment success. Eradication therapy groups were treated with antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and bismuth, while control groups were treated with placebo, prokinetics, and/or proton pump inhibitors. Primary analysis demonstrated that 1183 (40%) of 2939 patients in the eradication therapy group and 795 (32%) of 2468 in the control groups had no or mild symptoms during the last follow-up visit (pooled RR = 1.23; 95%CI: 1.12-1.36, P < 0.0001). Although there was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 42%) among the selected studies, the asymmetry in the funnel plot (Figure 3) indicated existing publication bias. H. pylori eradication therapy demonstrated symptom improvement at long-term (≥ 1 year) (RR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.12-1.37, P < 0.0001) but not at short-term (< 1 year) (RR = 1.26; 95%CI: 0.83-1.92, P = 0.27) follow-up. The studies that reported short-term outcomes demonstrated significant heterogeneity (I2 = 64%). The forest plot and sensitivity analysis are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of included studies for potential publication bias. The funnel plot was not absolutely symmetrical.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on symptom relief. Twenty-three studies were included. The random effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied.

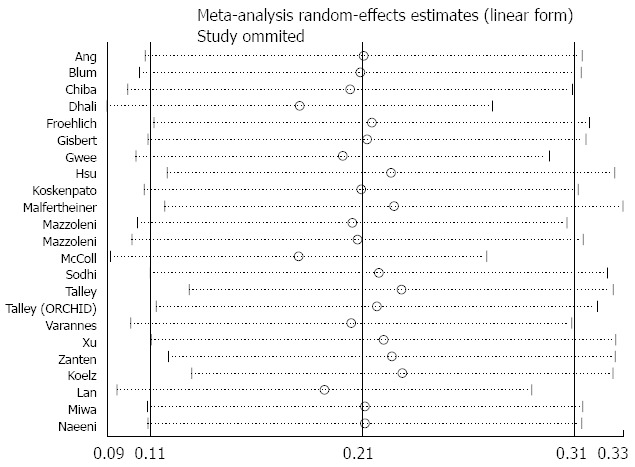

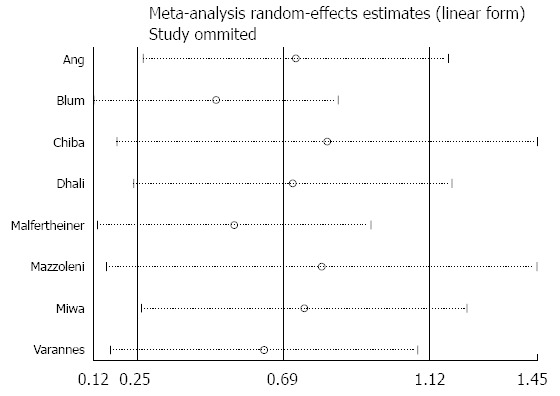

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on symptom relief.

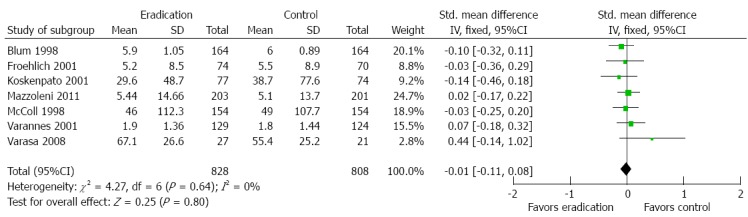

Benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy on quality of life

Seven studies reported data on quality of life both at baseline and at the last visit required for the meta-analysis. Five trials used the SF-36, one used the general well-being index, and one used QoL-PEI. A fixed effect model (I2 = 0%) was performed on all seven studies. Overall, H. pylori eradication therapy had no significant benefit on quality of life, with an SMD of -0.01 (95%CI: -0.11 to 0.08, P = 0.80). Detailed information is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on quality of life. Seven studies were included. The fixed effect model (Inverse Variance method) was applied.

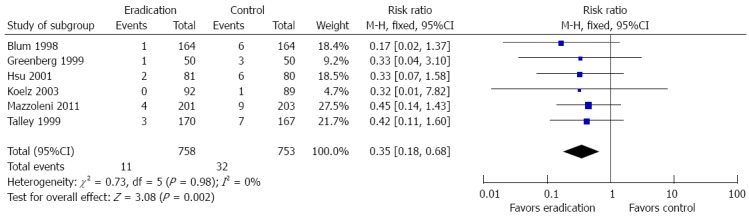

Benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy on long-term peptic ulceration

Six studies reported endoscopic data at the last visit to evaluate for the development of peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori eradication therapy compared to no eradication therapy reduced the development of peptic ulcer disease (RR = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.18-0.68, P = 0.002). There was no significant study heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Detailed information is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on long-term peptic ulceration. Six studies were included. The fixed effect (Inverse Variance method) model was applied.

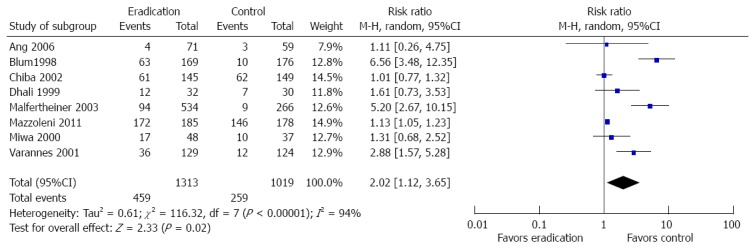

H. pylori eradication therapy on the development of adverse events

Eight studies provided data on development of common side effects associated with the intervention. Patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy were more likely to have side effects compared to controls (RR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.12-3.65, P = 0.02). The random effect model was used because significant study heterogeneity (I2 = 94%) was detected. The forest plot and sensitivity analysis are shown in Figures 8 and 9.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on adverse events. Eight studies were included. The random effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on adverse events.

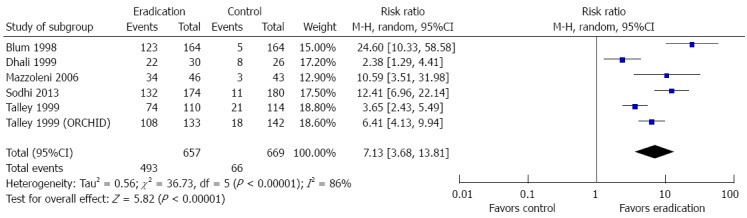

Other outcomes comparing H. pylori eradication therapy and control groups

One study provided outcome data on the cost of interventions such as medication, diagnostic tests, and physician consultation and did not demonstrate a difference between eradication therapy and the control[38]. However, the cost of intervention from this study was derived from utilization of healthcare services rather than the actual cost. Ten studies reported histological outcomes following intervention (Figure 10). Patients who received H. pylori eradication therapy were more likely to obtain histologic resolution of chronic gastritis compared to control (RR = 7.13; 95%CI: 3.68-13.81, P < 0.00001).

Figure 10.

Forest plot of the effects comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs control on histologic resolution of chronic gastritis. Six studies were included. The random effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied.

DISCUSSION

Our meta-analysis based on well-designed RCTs demonstrated that the effect size of symptom relief from H. pylori eradication therapy in patients with FD was small (RR = 1.23; 95%CI: 1.12-1.36, P < 0.0001) with an undetectable short-term benefit. Eradication therapy was nearly three times more likely to reduce the development of peptic ulcer disease compared with no eradication therapy. Furthermore, histologic findings of chronic gastritis were more likely to resolve after H. pylori eradication therapy compared to controls. However, H. pylori eradication therapy did not improve the quality of life for patients with FD compared to anti-acids, prokinetics, or placebo therapy. Eradication therapy was also more likely to be associated with side effects (RR = 2.02; 95%CI: 1.12-3.65, P = 0.02) compared to control.

H. pylori infection is more prevalent in Asia than in Western countries with high prevalence observed in China and South Korea[40]. Eradication therapy appears to be more effective in Asian populations as shown by the meta-analysis conducted by Jin and Li[13] on the Chinese population. Their study showed that H. pylori eradication therapy compared to controls increased the likelihood of improvement in dyspeptic symptoms by 3.6-fold. Another meta-analysis performed by Zhao et al[12] found that H. pylori eradication therapy compared to no eradication therapy was beneficial for improvement of dyspepsia in European (OR = 1.49; 95 CI% 1.10-2.02) and American populations (OR = 1.43; 95%CI: 1.12-1.83).

H. pylori is strongly associated with many diseases, including functional dyspepsia, gastric or duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[41,42]. However, H. pylori-induced gastritis is the most important risk factor for development of peptic ulcer disease[43]. Most patients with H. pylori infection have asymptomatic gastritis, and experience variable clinical symptoms depending on bacteria, host, and environmental factors. Whether H. pylori infection delays gastric emptying is unclear[44,45], but H. pylori appears to alter gastric acid production by changing gastrin and somatostatin secretion[46]. Abnormal gastric acid secretion causes mainly dysmotility-like, dyspeptic symptoms[47]. Duodenal acid exposure indirectly induces fullness, bloating, and epigastric pain by suppressing antral contractions, which may contribute to delayed gastric emptying[48,49].

According to the results of this meta-analysis, decision to eradicate H. pylori may be influenced by several key points. First, eradication therapy may be preferable among patients with risk factors for peptic ulcer disease or gastric cancer. Our study showed long-term benefits such as reduction in incidence of future peptic ulcer disease and resolution of gastritis, which are associated with gastric cancer[50,51]. Second, because of apparent adverse effects associated with eradication therapy, alternative validated therapy for FD such as acid suppression, prokinetics, or lifestyle changes for mild dyspeptic symptoms should also be considered. A large study of 1425 patients showed that H. pylori infection was a significant risk factor for dyspepsia. However, other factors such as NSAIDs use, unemployment, and heavy smoking demonstrated larger magnitude of association compared to H pylori infection[52]. Furthermore, rising prevalence of antibiotics resistance[53] and H. pylori reinfection[54] cannot be ignored. Third, it has been well established that the presence of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety disorder, is more common in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders than in the general population[55,56]. Psychiatric treatment with antidepressants is helpful in the reduction of dyspeptic symptoms[57]. Anxiety and depression are considered to be the best predictors of quality of life[58]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), psychotherapy, anxiolytics, and antidepressants can also relieve dyspeptic symptoms[59,60].

The strength of this meta-analysis includes a comprehensive analysis of high-quality studies with evaluation of various FD outcomes other than symptom improvement alone. There are some limitations to this meta-analysis. First, some well-designed studies were excluded because they were published in non-English language. Second, the random effect model was chosen to evaluate the short-term symptom improvement and development of adverse events in the presence of significant study heterogeneity resulting from different study designs and methods. Third, there is a possibility of publication bias as we excluded some RCTs that did not have sufficient data for meta-analysis or were not published in manuscript form at the time of submission.

In conclusion, H. pylori eradication therapy compared to no eradication therapy has a statistically significant but small magnitude of benefit for symptom relief and can also reduce the development of peptic ulcer disease. However, H. pylori eradication therapy was associated with higher incidence of adverse events during the treatment and failed to demonstrate any effect in improving the quality of life. In addition to H. pylori eradication therapy, alternative therapies such as acid-suppression, prokinetics, psychotherapy, and anxiolytics should also be considered after an individualized assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank professor Yun-Xian Yu for reviewing the statistical methods of this study.

COMMENTS

Background

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder and affects as many as 21% of the population worldwide. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is one of the most important factors for development of dyspeptic symptoms.

Research frontiers

Benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy in patients with FD are not consistent. Relying on antibiotics may lead to an increased rate of drug resistance, which may consequently lead to an increased rate of eradication failure.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Compared to previous studies, the current meta-analysis included additional clinical outcomes on the benefits of H. pylori eradication therapy other than symptom relief such as quality of life, adverse events, and development of peptic ulceration.

Applications

According to the current meta-analysis, H. pylori eradication therapy should be considered after individual assessment. The authors have highlighted that H. pylori eradication therapy was significantly beneficial for symptom relief and reduced the risk of development of peptic ulceration in patients with functional dyspepsia. However, H. pylori eradication therapy failed to improve the quality of life and was associated with higher likelihood of treatment-related adverse effects. Otherwise, alternative validated therapies such as acid suppression, prokinetics, and psychiatric treatment should also be considered.

Peer-review

The conclusions are warranted by the results, and it is a useful meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict-of-interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 1, 2015

First decision: December 21, 2015

Article in press: January 30, 2016

P- Reviewer: Ananthakrishnan N, Kurtoglu E, Lember M, Otegbayo JA S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, Moayyedi P. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049–1057. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y, Zou D, Wang R, Ma X, Yan X, Man X, Gao L, Fang J, Yan H, Kang X, et al. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in China: a population-based endoscopy study of prevalence and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:562–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Nie Y, Sha W, Su H. The link between psychosocial factors and functional dyspepsia: an epidemiological study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2002;115:1082–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, Holtmann G, Hu P, Malagelada JR, Stanghellini V. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samsom M, Verhagen MA, vanBerge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Abnormal clearance of exogenous acid and increased acid sensitivity of the proximal duodenum in dyspeptic patients. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:515–520. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilmer A, Van Cutsem E, Andrioli A, Tack J, Coremans G, Janssens J. Ambulatory gastrojejunal manometry in severe motility-like dyspepsia: lack of correlation between dysmotility, symptoms, and gastric emptying. Gut. 1998;42:235–242. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Tana P, Mengoli C, Bergonzi M, Pagani E, Corazza GR. Fasting and postprandial gastric sensorimotor activity in functional dyspepsia: postprandial distress vs. epigastric pain syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1631–1639. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunding JA, Tefera S, Gilja OH, Hausken T, Bayati A, Rydholm H, Mattsson H, Berstad A. Rapid initial gastric emptying and hypersensitivity to gastric filling in functional dyspepsia: effects of duodenal lipids. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1028–1036. doi: 10.1080/00365520600590513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang SM, Jia L, Lei XG, Xu M, Wang SB, Liu J, Song M, Li WD. Incidence and psychological-behavioral characteristics of refractory functional dyspepsia: a large, multi-center, prospective investigation from China. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1932–1937. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong D. Helicobacter pylori infection and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;215:38–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Gabriel R, Pajares JM. [Helicobacter pylori infection and functional dyspepsia. Meta-analysis of efficacy of eradication therapy] Med Clin (Barc) 2002;118:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(02)72403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao B, Zhao J, Cheng WF, Shi WJ, Liu W, Pan XL, Zhang GX. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies with 12-month follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:241–247. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31829f2e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin X, Li YM. Systematic review and meta-analysis from Chinese literature: the association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and improvement of functional dyspepsia. Helicobacter. 2007;12:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, Forman D, Mason J, Innes M, Delaney B. Systematic review and economic evaluation of Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Dyspepsia Review Group. BMJ. 2000;321:659–664. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talley NJ, Vakil N, Ballard ED, Fennerty MB. Absence of benefit of eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1106–1111. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Fedorak RN, Lambert J, Cohen L, Vanjaka A. Absence of symptomatic benefit of lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin triple therapy in eradication of Helicobacter pylori positive, functional (nonulcer) dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1963–1969. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Ott EA, Barros SG, Francesconi CF, Polanczyk CA, Wortmann AC, Theil AL, Fritscher LG, Rivero LF, et al. Clinical outcomes of eradication of Helicobacter pylori in nonulcer dyspepsia in a population with a high prevalence of infection: results of a 12-month randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miwa H, Hirai S, Nagahara A, Murai T, Nishira T, Kikuchi S, Takei Y, Watanabe S, Sato N. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection does not improve symptoms in non-ulcer dyspepsia patients-a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:317–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh-Naeeni M, Saberi-Firoozi M, Pourkhajeh A, Taheri H, Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Massarrat S. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication or of ranitidine plus metoclopramide on Helicobacter pylori-positive functional dyspepsia. A randomized, controlled follow-up study. Digestion. 2002;66:92–98. doi: 10.1159/000065589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Artaza Varasa T, Valle Muñoz J, Pérez-Grueso MJ, García Vela A, Martín Escobedo R, Rodríguez Merlo R, Cuena Boy R, Carrobles Jiménez JM. [Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on patients with functional dyspepsia] Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:532–539. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley NJ, Janssens J, Lauritsen K, Rácz I, Bolling-Sternevald E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial with 12 months’ follow up. The Optimal Regimen Cures Helicobacter Induced Dyspepsia (ORCHID) Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:833–837. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7187.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Tseng HH, Lo GH, Lo CC, Lin CK, Cheng JS, Chan HH, Ku MK, Peng NJ, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents ulcer development in patients with ulcer-like functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskenpato J, Farkkilä M, Sipponen P. Helicobacter pylori eradication and standardized 3-month omeprazole therapy in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2866–2872. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Francesconi CF, Mazzoleni F, Uchoa DM, De Bona LR, Milbradt TC, Von Reisswitz PS, Berwanger O, Bressel M, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication in functional dyspepsia: HEROES trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1929–1936. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malfertheiner P, MOssner J, Fischbach W, Layer P, Leodolter A, Stolte M, Demleitner K, Fuchs W. Helicobacter pylori eradication is beneficial in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:615–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Hildebrand P, Schneider C, Saraga E, Beglinger C, Vader JP. Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment does not benefit patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2329–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ang TL, Fock KM, Teo EK, Chan YH, Ng TM, Chua TS, Tan JY. Helicobacter pylori eradication versus prokinetics in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind study. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:647–653. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gisbert JP, Cruzado AI, Garcia-Gravalos R, Pajares JM. Lack of benefit of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with functional dyspepsia. Randomized one-year follow-up study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum AL, Talley NJ, O’Moráin C, van Zanten SV, Labenz J, Stolte M, Louw JA, Stubberöd A, Theodórs A, Sundin M, et al. Lack of effect of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Omeprazole plus Clarithromycin and Amoxicillin Effect One Year after Treatment (OCAY) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1875–1881. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg PD, Cello JP. Lack of effect of treatment for Helicobacter pylori on symptoms of nonulcer dyspepsia. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2283–2288. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.19.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sodhi JS, Javid G, Zargar SA, Tufail S, Shah A, Khan BA, Yattoo GN, Gulzar GM, Khan MA, Lone MI, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the effect of its eradication on symptoms of functional dyspepsia in Kashmir, India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:808–813. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwee KA, Teng L, Wong RK, Ho KY, Sutedja DS, Yeoh KG. The response of Asian patients with functional dyspepsia to eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:417–424. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328317b89e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhali GK, Garg PK, Sharma MP. Role of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment in H. pylori-positive and cytoprotective drugs in H. pylori-negative, non-ulcer dyspepsia: results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in Asian Indians. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:523–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu S, Wan X, Zheng X, Zhou Y, Song Z, Cheng M, Du Y, Hou X. Symptom improvement after helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with functional dyspepsia-A multicenter, randomized, prospective cohort study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6:747–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan L, Yu J, Chen YL, Zhong YL, Zhang H, Jia CH, Yuan Y, Liu BW. Symptom-based tendencies of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3242–3247. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McColl K, Murray L, El-Omar E, Dickson A, El-Nujumi A, Wirz A, Kelman A, Penny C, Knill-Jones R, Hilditch T. Symptomatic benefit from eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1869–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruley Des Varannes S, Fléjou JF, Colin R, Zaïm M, Meunier A, Bidaut-Mazel C. There are some benefits for eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1177–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiba N, Van Zanten SJ, Sinclair P, Ferguson RA, Escobedo S, Grace E. Treating Helicobacter pylori infection in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: the Canadian adult dyspepsia empiric treatment-Helicobacter pylori positive (CADET-Hp) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324:1012–1016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7344.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koelz HR, Arnold R, Stolte M, Fischer M, Blum AL. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia resistant to conventional management: a double blind randomised trial with a six month follow up. Gut. 2003;52:40–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19 Suppl 1:1–5. doi: 10.1111/hel.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Sherman PM. Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer and nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic overview. CMAJ. 1994;150:177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potamitis GS, Axon AT. Helicobacter pylori and Nonmalignant Diseases. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:26–29. doi: 10.1111/hel.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki H, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori infection in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarnelli G, Cuomo R, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptom patterns and pathophysiological mechanisms in dyspeptic patients with and without Helicobacter pylori. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2229–2236. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000007856.71462.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.el-Omar E, Penman I, Dorrian CA, Ardill JE, McColl KE. Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection lowers gastrin mediated acid secretion by two thirds in patients with duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1993;34:1060–1065. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miwa H, Nakajima K, Yamaguchi K, Fujimoto K, Veldhuyzen VAN Zanten SJ, Kinoshita Y, Adachi K, Kusunoki H, Haruma K. Generation of dyspeptic symptoms by direct acid infusion into the stomach of healthy Japanese subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee KJ, Vos R, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of duodenal acidification on the sensorimotor function of the proximal stomach in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G278–G284. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00086.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee KJ, Demarchi B, Demedts I, Sifrim D, Raeymaekers P, Tack J. A pilot study on duodenal acid exposure and its relationship to symptoms in functional dyspepsia with prominent nausea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1765–1773. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki H, Iwasaki E, Hibi T. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:79–87. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venerito M, Vasapolli R, Rokkas T, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori and Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:36–39. doi: 10.1111/hel.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wildner-Christensen M, Hansen JM, De Muckadell OB. Risk factors for dyspepsia in a general population: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cigarette smoking and unemployment are more important than Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:149–154. doi: 10.1080/00365520510024070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Georgopoulos SD, Papastergiou V, Karatapanis S. Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapies in the Era of Increasing Antibiotic Resistance: A Paradigm Shift to Improved Efficacy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:757926. doi: 10.1155/2012/757926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zendehdel N, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Malekzadeh R, Massarrat S, Sotoudeh M, Siavoshi F. Helicobacter pylori reinfection rate 3 years after successful eradication. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:401–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Persoons P, Demyttenaere K, Fischler B, Tack J. Relationship between anxiety and gastric sensorimotor function in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:455–463. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180600a4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Talley NJ, Herrick L, Locke GR. Antidepressants in functional dyspepsia. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:5–8. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haag S, Senf W, Häuser W, Tagay S, Grandt D, Heuft G, Gerken G, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Impairment of health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia and chronic liver disease: the influence of depression and anxiety. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:561–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, Creed F. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faramarzi M, Azadfallah P, Book HE, Rasolzadeh Tabatabai K, Taherim H, Kashifard M. The effect of psychotherapy in improving physical and psychiatric symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. Iran J Psychiatry. 2015;10:43–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]