Abstract

Current sexual assault risk reduction programs do not target alcohol use despite the widespread knowledge that alcohol use is a risk factor for being victimized. The current study assessed the effectiveness of a web-based combined sexual assault risk and alcohol use reduction program using a randomized control trial. A total of 207 college women between the ages of 18 and 20 who engaged in heavy episodic drinking were randomized to one of five conditions: full assessment only control condition, sexual assault risk reduction condition, alcohol use reduction condition, combined sexual assault risk and alcohol use reduction condition, and a minimal assessment only condition. Participants completed a 3-month follow-up survey on alcohol-related sexual assault outcomes, sexual assault outcomes, and alcohol use outcomes. Significant interactions revealed that women with higher incidence and severity of sexual assault at baseline experienced less incapacitated attempted or completed rapes, less incidence/severity of sexual assaults, and engaged in less heavy episodic drinking compared to the control condition at the 3-month follow-up. Web-based risk reduction programs targeting both sexual assault and alcohol use may be the most effective way to target the highest risk sample of college students for sexual assault: those with a sexual assault history and those who engage in heavy episodic drinking.

Keywords: sexual assault, sexual revictimization, alcohol, college women, web-based intervention

Sexual assault and alcohol use are common experiences for college women, with approximately 20% of women experiencing sexual assault while in college (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2007) and approximately 40% of college students engaging in heavy episodic drinking (HED; Mitka, 2009). Sexual assault is nonconsensual sexual contact ranging from sexual touching to penetration and HED is 4 drinks or more over a 2-hour period for women (NIAAA, 2004). Sexual assault and alcohol use often co-occur, with 50 to 70% of sexual assaults involving alcohol use (Abbey et al., 2004; Reed et al., 2009). Further, sexual assault victimization risk occurs when engaging in HED (Parks et al., 2008). Sexual assault and HED are particularly common for college women under the age of 21. In regards to sexual assault, high risk times include between the ages of 16 and 19 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006) and within the first year of college (Humphrey & White, 2000). Rates of HED have continued to increase for women under the age of 21 (Grucza, Norberg, & Bierut, 2009).

Sexual assault and alcohol use co-occurrence are prevalent and women who are intoxicated are more likely to be victimized (for a review, see Testa & Livingston, 2009) perhaps because they are targeted. Men’s perceptions of intoxicated women may increase a woman’s vulnerability to sexual assault because men may perceive intoxicated women to be more sexual (e.g., Abbey, Zawacki, & McAuslan, 2000; George et al., 1997). When men are intoxicated they are more likely to perceive ambiguous interactions with women to be more sexual than when sober (Farris, Treat, & Viken, 2010). Finally, some men use intoxication as a tactic for sexual assault, referred to as incapacitated rape. Additionally, alcohol use may increase a woman’s risk of sexual assault in part due to the cognitive impairments that can occur (e.g., alcohol myopia, Steele & Josephs, 1990) that can lead to less effective risk perception and lower likelihood of using effective resistance strategies (Norris et al., 2006; Stoner et al., 2007; Testa, Livingston, & Collins, 2000). Further, the environmental contextual risk of where drinking typically occurs (e.g., bars or college parties) can in itself put women at risk for sexual victimization (e.g., Fillmore, 1985; Parks & Miller, 1997).

Because of the high rates and co-occurrence of HED and sexual assault in college women under the age of 21, targeting this high-risk group of college women under the age of 21 who engage in HED to reduce sexual assault risk is warranted (Testa & Livingston, 2009). Two studies targeted alcohol use only in college women and reduced incapacitated sexual assault experiences (Clinton-Sherrod et al., 2011; Testa, Hoffman, Livingston, & Turrisi, 2010). However, targeting both alcohol and sexual assault risk perception and resistance strategies may be a more effective way to reduce all forms of sexual assault.

Sexual assault risk reduction (SARR) programs for college women

Existing SARR programs have two important limitations. First, there has been insufficient tailoring and targeting. SARR programs typically include general sexual assault education but do not target those at highest risk like women with a sexual assault history (Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Breitenbecher, 2000; Vladutiu et al., 2011). Further, women who engage in HED are not targeted in SARR programs and SARR programs are not tailored to individuals who engaged in HED to reduce alcohol use with evidence-based methodology. SARR programs also do not sufficiently target and tailor to the high-risk group of women who consume alcohol and have a sexual assault history.

Second, college SARR programs targeting female audiences are effective in changing sexual assault-related constructs (e.g., sexual assault knowledge, behavioral intent, and attitudes; Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Breitenbecher, 2000; Vladutiu et al., 2011), but are generally ineffective at decreasing sexual assault incidence or increasing use of SARR strategies. Moreover, women with a sexual assault history have had differential outcomes for SARR programs compared to women with no sexual assault history. Some studies have found that women with a sexual assault history do not benefit from the SARR programs (e.g., Hanson & Gidycz, 1993) and others have found that they do benefit (e.g., Gidycz et al., 2001; Mouilso, Calhoun, & Gidycz, 2011). When assessing the effectiveness of a SARR program, it is essential to consider the potential effects of sexual assault history. It is also essential to focus on theoretically-based components including sexual assault risk perception, resistance strategies, and barriers to resistance (Norris, Nurius, & Dimeff, 1996). The two most prominent theories regarding sexual assault victimization are the Cognitive Mediational Model (CMM; Nurius & Norris, 1996) and assess, acknowledge, and act (AAA; Rozee & Koss, 2001). Both of these theories posit that sexual assault risk perception (for a review, see Rich, Combs-Lane, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2004) and resistance (for a review, see Ullman, 2007) are important factors in sexual assault victimization and that although the perpetrator is at fault for the assault women can learn skills to increase their risk perception and use of effective resistance strategies. Nonetheless, because sexual assault is not the fault of the victim, sexual assault risk perception skills are not always associated with actual changes in victimization (for a review, see Gidycz, McNamara, & Edwards, 2006). According to these theories, there are several steps involved in effectively responding to a sexual assault. The first is the ability to perceive risk, or sexual assault risk perception. After perceiving risk, resistance strategies can be used if barriers to resistance do not get in the way (e.g., social pressure or alcohol use). The current SARR addresses risk perception, resistance strategies, and barriers to resistance.

Brief alcohol interventions for college students

It is imperative to target alcohol in SARR programs. Brief personalized feedback interventions are efficacious in reducing college student drinking and related harms (Dimeff et al., 1999; Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Miller et al., 2013; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, Elliot, Garey, & Carey, 2014). Feedback in these interventions includes a personalized summary of drinking and related consequences, moderation education, alcohol expectancies, and other didactic information using the spirit of motivational interviewing (e.g., Dimeff et al., 1999). Social norms are addressed in personalized feedback interventions where individuals are presented with a comparison of the individual’s drinking behavior, perceived drinking norms, and actual drinking norms. Given that previous research targeting alcohol use has effectively reduced incapacitated sexual assault experiences in college women (Clinton-Sherrod et al., 2011; Testa et al., 2010), brief alcohol interventions should be included as a component of sexual assault risk reduction programming.

Web-Based Interventions

Web-based personalized feedback interventions can be particularly useful for college students. Web-based interventions are easier to disseminate than in person interventions due to cheaper costs and less participant demands. Many universities require incoming students to participate in education programs and currently there are no regulations on what must be presented. There is evidence that web-based formats are useful in reducing alcohol use (for a review, see Larimer & Cronce, 2007) and in reducing sexual-risk behaviors (e.g. Lewis et al., 2014) in college students. Thus, a web-based SARR program for college women may be useful. Survey research suggests that participants are likely to report private information, like sexual experiences, in a computer-based format (Turner et al., 1998). Therefore, web-based SARR programs may facilitate honest responding and active participation which may help facilitate learning, especially for women with a sexual assault history.

Combined Interventions

Targeting both alcohol use and sexual assault risk may be the most effective way to reduce sexual assault on college campuses. Interventions that target two health outcomes (e.g., alcohol use and sexual-risk behaviors) suggest that combined interventions can be effective in reducing targeted behaviors (e.g. Lewis et al., 2014). Furthermore, excluding alcohol use from SARR provides an incomplete picture regarding how to reduce risk of being targeted for sexual assault in college. Combining personalized feedback for alcohol use with a SARR program may be an effective approach for decreasing sexual assault.

Current Study

The current study was a randomized control trial targeting both sexual assault risk and alcohol use in college women who engage HED using web-based personalized feedback. Three personalized feedback conditions (alcohol only, SARR only, and combined alcohol and SARR) and a minimal assessment only condition were compared to control condition (assessment only) on drinking related and sexual assault risk factors.

It was hypothesized (Hypothesis 1) that participants in the combined condition would have greater changes in alcohol-related sexual assault outcomes than the full assessment only control condition and that the effects would be stronger for women with higher sexual assault severity at baseline.

It was hypothesized (Hypothesis 2) that participants in the conditions with SARR components (SARR condition and combined condition) would have greater changes in sexual assault-related outcomes compared to the full assessment only control condition and that the effects would be stronger for women with higher sexual assault incidence/severity at baseline.

It was hypothesized (Hypothesis 3) that participants in the conditions with alcohol components (alcohol only condition and combined condition) would have greater changes in drinking-related outcomes compared to the full assessment only control condition.

Method

Participants

A total of 674 participants began the web-based screening assessment, 264 (39.17%) were eligible and enrolled in the study. Participants were eligible for the larger study if they were a) female, b) reported consumption of 4 drinks over a 2 hour period at least once in the past month, and c) were between the ages of 18 and 20. Participants were recruited from introductory psychology courses for a study about “drinking and sexual behaviors.” Students in these courses are generally representative both demographically and in terms of alcohol use of the campus (Neighbors et al., 2004).

Analyses included those who began the follow-up survey (N = 207; 78.41%) whether or not they viewed the personalized feedback. Those that participated in the follow-up survey were considered completers. Completers compared to non-completers did not significantly differ on baseline measures except that completers drank less (M = 9.25; SD = 7.28) than non-completers (M = 11.57; SD = 7.78), t(261) = 2.10, p = .037. At baseline, the participants were on average 18.77 years old (SD =.76). The majority of participants reported they were freshman (61.10%), were not members of a sorority (65.00%), lived on campus or in a sorority house (72.90%), and were not in a serious relationship (71.50%). Participants identified as 57.60% White, 20.50% Asian American/Pacific Islander, 14.10% multiracial, 3.90% Black/African American, 2.90% other, 1.00% Native American, and 9.50% Hispanic/Latina.

Measures

Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault: Intoxicated Attempted or Completed Rape

Items from the revised Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; see Koss et al., 2007) assessed intoxicated attempted or completed rape at follow-up. Participants were asked to indicate how many times (0, 1, 2, or 3 or more) they have had attempted or completed penetrative sex by incapacitation in the past 3 months. The original SES was a reliable and valid measure (Koss & Gidycz, 1985) and the revised SES was developed by a team of experts (Koss et al., 2007).

Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault: Risk Perception of Alcohol-Involved Rape

Participants estimated the likelihood in a percentage that they will experience nonconsensual sex while being incapacitated by alcohol by a man that they know while in college using a question developed by the research team. Estimations were made both at baseline and at follow-up and participants could enter numbers ranging from 0 to 100 to estimate percentage likelihood.

Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault: Alcohol Use before Sexual Activity

Participants were also asked how often they consume alcohol prior to or during sexual activity using a question developed by the research team. Answer choices were on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 1 = about a quarter of the time, 2 = about half of the time, 3 = about three quarters of the time, and 4 = always). Alcohol use before sexual activity was reported both at baseline and at follow-up indicating behavior in the past 3 months.

Sexual Assault: Sexual Assault Incidence/Severity

Using the SES (see Koss et al., 2007), participants indicated if they have had coerced sexual experiences at three time points: after their 14th birthday but before entering college (baseline), since entering college (baseline), and in the past 3 months (follow-up). Baseline experiences were combined. The SES is a behaviorally specific assessment and it includes experiences perpetrated by verbal coercion, incapacitation, threats of physical force, and physical force. Sexual assault experiences include sexual contact, attempted penetration, and completed penetration. Participants were asked to indicate the number of times that a tactic or multiple tactics were used for each of the experiences (0 = 0 times, 1 = 1 time, 2 = 2 times, and 3 = 3 or more times). The original SES was a reliable and valid measure (Koss & Gidycz, 1985) and the revised SES was developed by a team of experts (Koss et al., 2007).

Sexual assault incidence and severity was scored using a 63-point scale (Davis et al., 2014) for each time point (baseline and follow-up), with high scores indicating more severe sexual assault experiences and zeros indicating no sexual assault experiences. This scoring procedure takes into account both frequency of experiences and severity of experiences. It was calculated using the procedures outlined in Davis et al. (2014) by multiplying a severity score by number of times each has been experienced.

Sexual Assault: Verbally Coerced Sexual Assault Risk Perception

Participants estimated the likelihood (percentage) of experiencing verbally coerced nonconsensual sex by a man that they know while in college at baseline and follow-up using an open-ended question developed by the research team where participants wrote an estimated percentage. Participants could enter numbers ranging from 0 to 100 to estimate percentage likelihood.

Sexual Assault: Protective Behavioral Strategies

Sexual assault PBS were assessed using a revised version of the Dating Self-Protection against Rape Scale which consisted of 15 items (Moore & Waterman, 1999; Breitenbecher, 2008). Participants indicated how often they engaged in behaviors (e.g., “provide your own transportation” and “meet in a public place instead of a private place”) when they were with a date (and revised to include “or someone who is sexually interested in you”). Answer choices ranged on a 5-point scale (1 = Never and 5 = Always). Scores were computed by creating an average of all items for baseline and follow-up. Items had excellent internal consistency (α = .88). This measure has been found to be reliable and valid (Breitenbecher, 2008; Moore & Waterman, 1999).

Alcohol Use: Drinks per Week

Participants indicated the number of drinks typically consumed each day of their average week in the past 30 days using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) at baseline. Average drinks per week were calculated by summing the drinks consumed each day.

Alcohol Use: HED Frequency

HED frequency was assessed by asking “How often did you have 4 or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a 2 hour period” in the past month at baseline and in the past 3 months at follow-up. Answer choices ranged from 0 times in the past month to everyday.

Alcohol Use: Drinking Norms

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991) was used to determine participants’ perception of alcohol use at the participant’s university. Participants were asked how many drinks they perceived the typical female student at the participant’s university drinks on each day of the week at baseline and follow-up. Average perceived drinks per week were calculated by adding the number of perceived drinks per day.

Alcohol Use: Protective Behavioral Strategies

Participants were asked 15 items from the Protective Behavioral Strategies (Martens, Ferrier, Sheehy, Corbett, Anderson, & Simmons, 2005), with answer choices ranging on a 5-point scale (1 = always and 5 = never). Items were reverse scored (1 = never and 5 = always). Participants were asked while using alcohol or “partying” whether they engaged in behaviors (e.g. “determine not to exceed a set number of drinks,” “avoid mixing different types of alcohol,” and “know where your drink had been at all times”). Items were averaged for a total drinking PBS score (α = .94) at baseline and follow-up rather than using subscale scores given that we were primarily interested in overall use of drinking protective behavioral strategies. This measure has been found to be valid (Martens et al., 2005).

Study Conditions

SARR Only Condition

The current sexual assault risk reduction program adapted evidence- and theory-based components to a web-based format. These components were chosen based on the CMM and AAA, therefore, there was a heavy focus on sexual assault risk perception and resistance strategies in the current web-based sexual assault risk reduction program. The first component of the intervention was sexual assault education. This included campus- and state-specific definitions of sexual assault as well as risk factors for sexual assault (e.g., information on high risk locations and research on potential perpetrator characteristics). The education component also included personalized feedback regarding estimated likelihood of being sexually assaulted while in college directly compared with actual sexual assault rates at their university in a graph form. For example, participants were given feedback like “According to the information you gave us in the survey, you believe that 10% of (insert university) female students who drink have been raped. According to the students surveyed, 25% of (insert university) female students who drink have been raped” and a graph was presented. The second component was sexual assault risk reduction strategies and skills. In this component, a sexual assault scenario (Messman-Moore & Brown, 2006) was presented and participants chose what sexual assault resistance strategy they would be most likely to use in the situation and were given personalized feedback on that strategy and a list of active resistance strategies (Ullman, 2007) that could be used. An example of feedback was “In the survey you indicated that you would try: Tell him clearly and directly that I want him to stop, this IS an active resistance strategy” and then provided with other active resistance strategies as examples. They were also given feedback on particular parts of the story that indicated sexual assault risk to target sexual assault risk perception. Because the CMM posits that cognitive barriers to sexual assault resistance may interfere with a woman’s use of active resistance strategies, barriers to resist sexual assault were addressed in the current risk reduction program. Individuals were given a list of common barriers to resistance including having friends in common with the perpetrator and provided with potential ways to address these barriers. For example, “Not knowing how: We provided you with some tips, feel free to click back to re-read them!” and “Fear of making things worse: It is a commonly believed myth that resisting sexual assault leads to worse outcomes. Resisting sexual assault can actually lead to better outcomes – women are less likely to be raped and they are less likely to be physically hurt! But as in every situation, women should use their best judgment.” Finally, participants were given local information regarding sexual assault and counseling resources.

Alcohol Only Condition

The current alcohol use reduction program was an already developed and tested web-based personalized feedback intervention using gender specific feedback (Neighbors et al., 2010). This web-based program included psychoeducation on alcohol including definitions of a standard drink, gender differences in blood alcohol content, explanation of alcohol expectancies and alcohol myopia, and personalized information about blood alcohol content and associated risks. It also included personalized feedback about alcohol-related negative consequences and drinking protective behavioral strategies. Finally, based on the social norms approach, participants were given feedback regarding their drinking behavior as compared to their perceived drinking norms and actual drinking norms at their university to correct misperceptions regarding normative drinking behavior.

Combined Alcohol and SARR Condition

A web-based combined alcohol use and sexual assault risk reduction program was developed by combining components from both the alcohol use and sexual assault risk reduction programs described earlier (see Figure 3 for an example). All components from both programs were used and information was integrated where possible. For example, sexual assault examples were used in the alcohol psychoeducation components and statistics for alcohol-involved sexual assault was presented in the sexual assault statistics components.

Figure 3.

Combined feedback example.

Assessment Only Conditions

The current study included two assessment only conditions. For both of these conditions, participants received no feedback. The main control group was a full assessment control condition where participants completed the same baseline assessment as those in the intervention conditions. A second assessment only condition was included as a comparison to the control condition. This was a minimal assessment only condition, which was included to control for the possibility of extended assessment regarding alcohol use in itself changing alcohol use. This minimal assessment only condition did not include questions about drinking norms and drinking PBS.

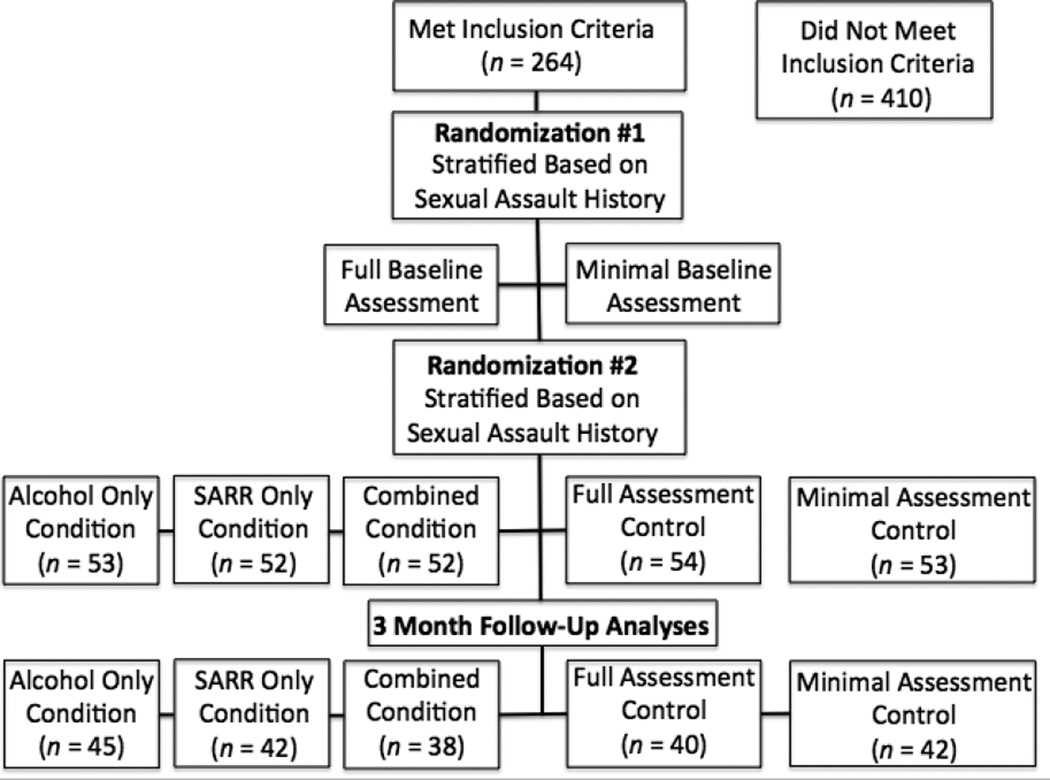

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the university’s IRB. Participants completed the baseline screening survey online and were given course credit. Once participants had been deemed eligible to participate in the study, they were randomly assigned stratified by sexual assault history to either a minimal assessment (20%) or a full assessment (80%). Participants assigned to complete the full assessment and were then randomly assigned stratified by sexual assault history to one of four conditions: 1. Alcohol Only Condition 2. SARR Only Condition 3. Combined Condition 4. Full Assessment Only Control Condition. Those in the Alcohol Only, SARR Only, and Combined conditions received the web-based intervention immediately following the completion of the survey. All participants were contacted 3 months after completing the survey to complete the follow-up survey and were given a $25 electronic gift card for participation (see Figure 1). The follow-up survey was the same for all conditions.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of procedures.

Participants were invited to complete a brief feedback survey after baseline to assess participants’ behavior during the procedures since they were not in the lab and 221 (83.71%) completed this survey. The majority of participants reported not using drugs or alcohol during the study (92.42%) and reported not being distracted (M = 2.10, SD = 1.32; 1 = Not distracted at all, 7 = Highly distracted).

Data Analytic Plan

Each condition (minimal assessment control condition, combined condition, alcohol only condition, and sexual assault only condition) was compared with the full assessment only control condition for each of the drinking, sexual assault, and combined outcomes separately using hierarchical regressions. For all hierarchical regressions, sexual assault incidence/severity was controlled for in the first step along with the baseline measure of the outcome variable. Additionally, for outcomes that were not alcohol-related, drinks consumed per week were controlled for in the first step (alcohol-related variables included the relevant alcohol-related baseline variable as a control variable). In the second step, each condition was entered to compare to the full assessment only control condition. In the third step, interactions by sexual assault incidence/severity at baseline were included. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted over other analytic strategies to examine interactions with each intervention condition and to facilitate interpretation of graphed interactions. To ensure that randomization occurred successfully as outlined above, each outcome variable was examined at baseline for differences by condition.

Results

Descriptive Results and Initial Analyses

On average, it took 112.93 days (SD = 45.29) to complete the follow-up survey after the baseline survey. Because participants completed the follow-up survey at different times, days between baseline and follow-up were controlled for in the analyses.

Participants in the minimal assessment only condition did not receive baseline questions regarding drinking norms or drinking PBS, therefore, that group was excluded from the analyses for those outcomes only. The minimal assessment only condition was compared to the full assessment only condition for all other outcomes. Initial ANOVAs revealed no differences at baseline between conditions (see Tables 1 and 2 for descriptive information). Data were checked for normality and multicollinearity. In cases where variables that did not have a normal distribution, analyses were re-run with transformed data. However, results did not change and we therefore only presented non-transformed data in the current paper.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault Outcomes and Sexual Assault Outcomes by Condition

| Full Assessment Control |

Alcohol Only Condition |

SARR Only Condition |

Combined Condition |

Minimal Assessment Control |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Assessment | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Incapacitated Attempted or Completed Rape |

Baseline | .65 | 1.00 | .62 | 1.09 | .74 | 1.19 | .55 | .95 | .69 | 1.24 |

| Follow-Up | .31 | .80 | .35 | .87 | .18 | .60 | .02 | .16 | .15 | .533 | |

| Perceived Likelihood of Incapacitated Rape |

Baseline | 3.76 | 6.71 | 15.21 | 23.66 | 12.55 | 20.56 | 11.23 | 18.54 | 9.85 | 17.78 |

| Follow-Up | 6.38 | 10.45 | 10.16 | 17.70 | 16.46 | 22.14 | 12.06 | 13.45 | 9.18 | 20.24 | |

| Use of Alcohol before Sex | Baseline | 1.02 | 1.12 | .96 | .88 | 1.05 | 1.13 | .89 | .92 | .81 | .83 |

| Follow-Up | 1.05 | 1.34 | .98 | .97 | .98 | 1.21 | .95 | 1.04 | .63 | .83 | |

| Sexual Assault Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Sexual Assault Incidence and Severity |

Baseline | 8.05 | 10.45 | 9.89 | 13.71 | 8.86 | 13.72 | 9.08 | 12.26 | 8.90 | 13.00 |

| Follow-Up | 3.10 | 6.54 | 5.72 | 15.66 | 3.62 | 10.05 | 1.27 | 2.80 | 3.08 | 9.27 | |

| Perceived Likelihood of Verbally Coerced Rape |

Baseline | 12.28 | 18.93 | 21.27 | 26.39 | 16.07 | 22.10 | 17.81 | 28.02 | 14.07 | 22.67 |

| Follow-Up | 11.27 | 18.06 | 17.37 | 26.44 | 22.79 | 26.03 | 16.03 | 18.73 | 16.51 | 24.51 | |

| Use of Sexual Assault PBS | Baseline | 2.43 | 1.05 | 2.54 | .85 | 2.61 | .86 | 2.36 | .76 | 2.44 | .97 |

| Follow-Up | 2.78 | 1.09 | 2.47 | 1.04 | 2.68 | 1.36 | 2.55 | .88 | 2.51 | 1.46 | |

| Alcohol Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Frequency of HED | Baseline | 2.48 | 1.38 | 2.44 | 1.27 | 2.33 | 1.26 | 2.32 | 1.51 | 2.60 | 1.42 |

| Follow-Up | 2.23 | 1.50 | 1.78 | 1.17 | 1.73 | 1.32 | 2.03 | 1.59 | 1.88 | 1.57 | |

| Drinking Norms | Baseline | 17.05 | 11.94 | 16.16 | 7.86 | 15.07 | 6.41 | 15.35 | 8.94 | - | - |

| Follow-Up | 14.84 | 8.63 | 10.61 | 5.96 | 16.53 | 11.81 | 12.78 | 8.69 | 13.59 | 7.90 | |

| Use of Drinking PBS | Baseline | 3.20 | .42 | 3.28 | .50 | 3.42 | .45 | 3.27 | .52 | - | - |

| Follow-Up | 2.77 | .62 | 2.53 | .59 | 2.57 | .60 | 2.70 | .60 | 2.50 | .73 | |

Table 2.

Correlations of Main Outcome Variables at Follow-Up

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Incapacitated Attempted or Completed Rape |

- | ||||||||

| 2. Perceived Likelihood of Incapacitated Rape |

0.182* | - | |||||||

| 3. Use of Alcohol before Sex | 0.201** | 0.294** | - | ||||||

| 4. Sexual Assault Severity | 0.824** | 0.204** | 0.248** | - | |||||

| 5. Perceived Likelihood of Verbally Coerced Rape |

0.133* | 0.709** | 0.285** | 0.169* | - | ||||

| 6. Use of Sexual Assault PBS | −0.193** | −0.094 | −0.150* | −0.214** | −0.095 | - | |||

| 7. Frequency of HED | 0.223** | 0.133 | 0.434** | 0.268** | 0.157* | −0.229** | - | ||

| 8. Drinking Norms | −0.025 | −0.032 | 0.160* | 0.000 | −0.007 | −0.064 | 0.227** | - | |

| 9. Use of Drinking PBS | −0.201** | −0.161* | −0.395** | −0.246** | −0.164* | 0.367** | −0.416** | −0.029 | - |

Note:

indicates p < .05,

indicates p < .01.

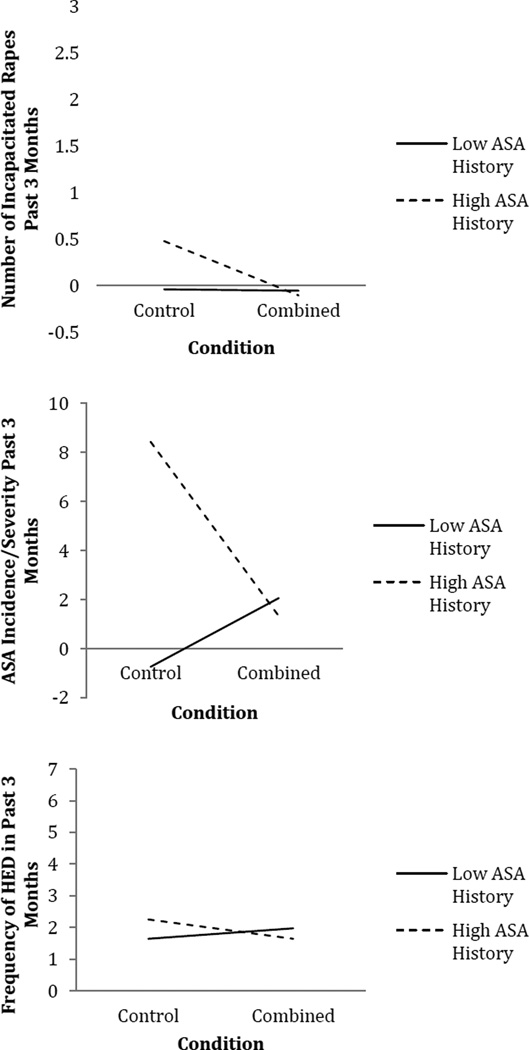

Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault

In regards to incapacitated attempted or completed rape, women with more severe ASA histories reported less incapacitated attempted or completed rape in the past 3 months (see Table 3). Women in the combined condition reported less incapacitated attempted or completed rape in the past 3 months than women in the full assessment only control condition. There was a significant interaction between the combined condition and severity of ASA history (see Figure 2). Tests of simple slopes revealed that the difference between combined condition and full assessment control condition was significant for women with more severe ASA histories (t = −2.997, p = .003) but not for women with less severe ASA histories (t = −.093, p = .926).

Table 3.

Alcohol-Related Sexual Assault Outcomes

| Incapacitated Attempted or Completed Rape Frequency | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | F | df | R2 | B | SE | t | β | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

|

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 12.461*** | (2,194) | 0.114 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 3.996 | 0.283*** | 0.008 | 0.023 |

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | 0.010 | 0.006 | 1.671 | 0.118 | −0.002 | 0.022 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 5.282*** | (6,190) | 0.143 | 0.020 | 0.137 | 0.150 | 0.013 | −0.249 | 0.290 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | −0.102 | 0.141 | −0.725 | −0.062 | −0.381 | 0.176 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −0.289 | 0.142 | −2.040 | −0.172* | −0.569 | −0.010 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | −0.156 | 0.139 | −1.119 | −0.096 | −0.430 | 0.119 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 4.666*** | (8,188) | 0.166 | −0.004 | 0.010 | −0.369 | −0.033 | −0.023 | 0.016 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.021 | 0.009 | −2.257 | −0.206* | −0.040 | −0.003 | |||

|

Perceived Likelihood of Experiencing Incapacitated Rape in College | ||||||||||

| 1 | Baseline Perceived Likelihood | 11.884*** | (3,183) | 0.163 | 0.256 | 0.065 | 3.915 | 0.276*** | 0.127 | 0.385 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.093 | 0.102 | 0.911 | 0.066 | −0.108 | 0.293 | |||

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | 0.476 | 0.168 | 2.834 | 0.204** | 0.145 | 0.807 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 6.068*** | (7,179) | 0.192 | 0.508 | 3.716 | 0.014 | 0.014 | −6.742 | 7.922 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | 0.590 | 3.868 | 0.185 | 0.185* | 0.689 | 15.954 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | 3.797 | 3.837 | 0.084 | 0.084 | −3.774 | 11.368 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | 1.301 | 3.756 | 0.030 | 0.030 | −6.110 | 8.712 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 5.030*** | (9,177) | 0.204 | 0.281 | 0.258 | 1.088 | 0.099 | −0.229 | 0.791 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.232 | 0.249 | −0.933 | −0.086 | −0.723 | 0.259 | |||

|

Frequency Use of Alcohol Before Sex | ||||||||||

| 1 | Baseline Use of Alcohol before Sex | 42.494*** | (3,199) | 0.390 | 0.098 | 0.069 | 8.080 | 0.501*** | 0.424 | 0.698 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.561 | 0.005 | 0.329 | 0.019 | −0.008 | 0.012 | |||

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | 0.029 | 0.009 | 3.234 | 0.205** | 0.011 | 0.047 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 18.580*** | (7,195) | 0.400 | −0.055 | 0.188 | −0.295 | −0.021 | −0.425 | 0.315 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | −0.068 | 0.194 | −0.351 | −0.025 | −0.450 | 0.314 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −0.047 | 0.195 | −0.240 | −0.017 | −0.432 | 0.338 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | −0.303 | 0.192 | −1.576 | −0.112 | −0.681 | 0.076 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 14.664*** | (9,193) | 0.406 | −0.011 | 0.013 | −0.856 | −0.063 | −0.038 | 0.015 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.017 | 0.013 | −1.266 | 0.207 | −0.096 | −0.042 | |||

Figure 2.

Interactions of combined condition and sexual assault incidence/severity at baseline on outcomes.

In regards to alcohol-involved rape risk perception, baseline perceived risk was significantly positively associated with perceived risk at follow-up (see Table 3). Women who drank more at baseline reported higher perceived likelihood of experiencing incapacitated rape in college. Women in the SARR only condition reported higher perceived likelihood of experiencing incapacitated rape while in college compared to women in the full assessment only control condition.

In regards to alcohol use before sexual activity, frequency of use of alcohol before sex at baseline and drinks per week were significantly positively associated with alcohol use before sex at follow-up (see Table 3). No significant main effects or interactions were found.

Sexual Assault

In regards to sexual assault severity, women with more severe ASA histories and who drank more at baseline experienced more incidence of and severity of ASA in the past 3 months at follow-up compared to those with less severe ASA histories and who drank less (see Table 4). There were no main effects of condition on sexual assault severity. There was a significant interaction between the combined condition and ASA severity history (see Figure 2). Women with more severe ASA histories reported less sexual assault severity in the past 3 months in the combined condition than in the full assessment only control condition. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that there was a significant difference between combined and full assessment only control condition for women with more severe ASA histories (t = −2.442, p = .016), but no difference for women with lower incidence and severity of sexual assault history (t = .963, p = .337).

Table 4.

Sexual Assault Outcomes

| ASA Incidence and Severity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | F | df | R2 | B | SE | t | β | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

|

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 19.438 | (2,194) | 0.167 | 0.273 | 0.056 | 4.872 | 0.334*** | 0.163 | 0.384 |

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | 0.205 | 0.090 | 2.270 | 0.156* | 0.027 | 0.383 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 7.245 | (6,190) | 0.186 | 0.207 | 0.091 | 1.105 | 0.093 | −1.769 | 6.273 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | 2.252 | 2.038 | 0.498 | 0.041 | −3.105 | 5.203 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −1.970 | 2.115 | −0.931 | −0.077 | −6.141 | 2.202 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | 0.049 | 2.077 | 0.024 | 0.002 | −4.047 | 4.146 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 6.475 | (8,188) | 0.216 | −0.049 | 0.144 | −0.339 | −0.025 | −0.332 | 0.235 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.369 | 0.139 | −2.660 | −0.196** | −0.643 | −0.095 | |||

|

Perceived Likelihood of Experiencing Verbally Coerced Rape in College | ||||||||||

| 1 | Baseline Perceived Likelihood | 8.610 | (3,184) | 0.123 | 0.180 | 0.071 | 2.547 | 0.189* | 0.041 | 0.319 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.301 | 0.141 | 2.128 | 0.161* | 0.022 | 0.580 | |||

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | 0.408 | 0.227 | 1.802 | 0.132 | −0.039 | 0.855 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 4.355 | (7,180) | 0.145 | 4.010 | 4.991 | 0.803 | 0.072 | −5.838 | 13.858 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | 10.943 | 5.204 | 2.103 | 0.183* | 0.675 | 21.212 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | 3.865 | 5.195 | 0.744 | 0.065 | −6.386 | 14.116 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | 4.820 | 5.050 | 0.954 | 0.084 | −5.145 | 14.785 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 3.827 | (9,178) | 0.162 | −0.015 | 0.360 | −0.041 | −0.004 | −0.726 | 0.696 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.635 | 0.340 | −1.865 | −0.177 | −1.307 | 0.037 | |||

|

Use of Sexual Assault PBS | ||||||||||

| 1 | Baseline Use of Sexual Assault PBS | 30.968*** | (3,190) | 0.328 | 0.755 | 0.081 | 9.306 | 0.566*** | 0.595 | 0.915 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | −0.002 | 0.006 | −0.342 | −0.021 | −0.014 | 0.010 | |||

| 1 | Weekly Drinking | −0.003 | 0.010 | −0.295 | −0.019 | −0.022 | 0.016 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 13.304*** | (7,186) | 0.334 | −0.257 | 0.220 | −1.168 | −0.090 | −0.692 | 0.177 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | −0.123 | 0.226 | −0.543 | −0.041 | −0.569 | 0.323 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −0.108 | 0.227 | −0.475 | −0.036 | −0.557 | 0.341 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | −0.176 | 0.225 | −0.781 | −0.060 | −0.619 | 0.268 | |||

| 3 | SARR Condition x ASA History | 10.550*** | (9,184) | 0.340 | −0.001 | 0.016 | −0.049 | −0.004 | −0.032 | 0.030 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | 0.020 | 0.015 | 1.324 | 0.109 | −0.010 | 0.050 | |||

In regards to risk perception of sexual assault by verbal coercion, perceived likelihood of experiencing verbally coerced rape at baseline was significantly positively associated with risk perception at follow-up (see Table 4). There was a main effect for SARR condition with women in the SARR condition reporting higher perceived likelihoods of experiencing verbally coerced rape in college compared to those in the full assessment only condition. No other significant main effects or interactions were found.

In regards to use of sexual assault PBS, use of sexual assault PBS at baseline was significantly associated with more use of PBS at follow-up (see Table 4). No significant main effects or interactions were found.

Alcohol Use

In regards to HED frequency, frequency of HED at baseline and ASA history severity were positively associated with frequency of HED at follow-up (see Table 5). There was a significant interaction between the combined condition and ASA history (see Figure 2). Women with more severe ASA histories reported engaging in HED less frequently in the combined condition compared to the full assessment control condition. Tests of the simple slopes indicated an approaching significant slope for women with more severe ASA histories (t = −1.881, p = .061) but no difference for women with less severe ASA histories (t = 1.052, p = .294).

Table 5.

Drinking Outcomes

| HED Frequency | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | F | df | R2 | B | SE | t | β | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

|

| 1 | Baseline HED | 39.200*** | (2,202) | 0.280 | 0.499 | 0.064 | 7.807 | 0.475*** | 0.373 | 0.625 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.018 | 0.007 | 2.578 | 0.157* | 0.004 | 0.031 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 13.929*** | (6,198) | 0.297 | −0.475 | 0.266 | −1.787 | −0.138 | −0.999 | 0.049 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | −0.428 | 0.272 | −1.575 | −0.120 | −0.964 | 0.108 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −0.147 | 0.277 | −0.532 | −0.040 | −0.693 | 0.399 | |||

| 2 | Minimal Assessment Only Control | −0.429 | 0.270 | −1.590 | −0.122 | −0.962 | 0.103 | |||

| 3 | Alcohol Condition x ASA History | 11.247*** | (8,196) | 0.315 | −0.012 | 0.016 | −0.726 | −0.061 | −0.043 | 0.020 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.041 | 0.018 | −2.253 | −0.183* | −0.078 | −0.005 | |||

|

Drinking Norms | ||||||||||

| 1 | Baseline Drinking Norms | 10.313*** | (2,157) | 0.116 | 0.352 | 0.077 | 4.541 | 0.341*** | 0.199 | 0.505 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.003 | 0.058 | 0.043 | 0.003 | −0.111 | 0.116 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 6.601*** | (5,154) | 0.176 | −4.124 | 1.864 | −2.213 | −0.201* | −7.805 | −0.442 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | 1.838 | 1.901 | 0.967 | 0.087 | −1.917 | 5.594 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −1.764 | 1.923 | −0.917 | −0.082 | −5.563 | 2.035 | |||

| 3 | Alcohol Condition x ASA History | 5.295*** | (7,152) | 0.159 | 0.078 | 0.130 | 0.596 | 0.067 | −0.180 | 0.335 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | 0.271 | 0.142 | 1.914 | 0.210 | −0.009 | 0.551 | |||

|

Use of Drinking PBS | ||||||||||

| 1 | Use of Drinking PBS at Baseline | 30.878*** | (2,156) | 0.284 | −0.662 | 0.090 | 7.313 | −0.522*** | −0.840 | −0.483 |

| 1 | ASA Severity Baseline | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.433 | 0.031 | −0.005 | 0.008 | |||

| 2 | Alcohol Only Condition | 13.010*** | (5,153) | 0.298 | −0.185 | 0.114 | −1.627 | −0.137 | −0.409 | 0.040 |

| 2 | SARR Only Condition | −0.071 | 0.118 | −0.598 | −0.050 | −0.304 | 0.163 | |||

| 2 | Combined Condition | −0.022 | 0.118 | −0.189 | −0.016 | −0.256 | 0.211 | |||

| 3 | Alcohol Condition x ASA History | 9.438*** | (7,151) | 0.304 | −0.008 | 0.008 | −1.103 | −0.113 | −0.023 | 0.007 |

| 3 | Combined Condition x ASA History | −0.001 | 0.008 | −0.108 | −0.011 | −0.018 | 0.016 | |||

Note. Minimal assessment condition was not included in drinking norms or use of sexual assault PBS because these variables were not assessed at baseline but was included in the analyses of HED.

In regards to drinking norms, drinking norms at baseline were positively associated with drinking norms at follow-up (see Table 5). There was a significant main effect for alcohol condition such that women in the alcohol condition reported lower perceived normative drinking behavior than those in the full assessment control condition. There were no other main effects or interactions.

In regards to drinking PBS, use of drinking PBS at baseline was positively associated with use of drinking PBS at follow-up (see Table 5). No significant main effects or interactions were found.

Discussion

The current paper focused on testing the effectiveness of targeting both sexual assault risk and alcohol use among college women who are at high risk of experiencing sexual assault. The combined condition was effective at reducing number of incapacitated rapes, sexual assault incidence and severity, and frequency of HED for women with more severe sexual assault histories. These findings indicate that a brief web-based personalized feedback intervention that targets both sexual assault risk and alcohol use can effectively reduce sexual assault experiences for women who are at highest risk: underage college women who engage in HED with a more severe sexual assault history. Although efforts should be developed to reduce sexual assault risk for all college women, those at highest risk are in need of a readily available intervention that can be easily disseminated.

These reductions are important for college women for three primary reasons. First, sexual assault rates are high amongst college women. This is alarming given that women with a sexual assault history are at the highest risk of experiencing a sexual assault. Secondly, SARR are generally ineffective in reducing sexual assault incidence rates. This may be because previously assessed SARR typically do not directly target alcohol use and barriers to resistance. Third, this web-based personalized feedback combined condition can be easily disseminated on college campuses. The costs of web-based interventions are extremely low compared to in-person interventions and the personalized nature of this intervention may help participants digest the information rather than dismiss it due to optimistic bias.

We did not find changes in drinking or sexual assault PBS with the intervention conditions, however, we speculate several possible reasons why the combined condition was effective at reducing sexual assault rates among women with more severe sexual assault histories. First, it is possible that women with more severe sexual assault histories were drinking to cope with the assault, which is one type of drinking motive or reasons for drinking. Perhaps a combined intervention targeting drinking and sexual assault altered drinking motives. Second, it’s possible that the combined condition was validating by providing information regarding alcohol use and sexual assault given that approximately half of sexual assaults involve alcohol. For example, information regarding alcohol’s effects on sexual assault experiences like being targeted for victimization based on alcohol consumption or information regarding alcohol myopia effects may be presented in a way where participants feel understood rather than blamed for their assault. This could be different from other programs that do not target alcohol use as overtly and also a difference from how others reacted if they disclosed an assault. Feeling understood could potentially reduce the likelihood of using maladaptive coping strategies. Future research should examine drinking motives and other potential factors to understand the mechanisms of change in the combined intervention.

We also found that sexual assault history severity and average drinking were associated with sexual assault severity at follow-up. Although this is not new information, it is important to note that even within a high risk group of underage college women who engage in HED, sexual assault history severity and average drinking are consistent risk factors for experiencing sexual assault at a later time point and interventions should target these risk factors to protect women from being targeted for these reasons.

Consistent with previous research, the alcohol only condition was effective at reducing drinking norms compared to those in the full assessment only control condition. Drinking norms were directly targeted in the intervention, suggesting that the mechanism that was targeted in the intervention was effective in that drinking norms were targeted and that is what was changed. However, previous research has found that when drinking norms are targeted in larger samples, web-based alcohol use reduction programs are effective.

The perceived likelihood of experiencing verbally coerced rape by an acquaintance while in college was also higher among individuals in the SARR only condition compared to the full assessment only control. This may be because sexual assault risk perception was directly targeted in the SARR program. Participants were shown the discrepancies between their perceived risk and their actual risk while in college. Similar to changes in drinking norms, this is what was targeted in the intervention and that was what changed. Future research should include larger samples and more time points to determine if this is a mediator of outcome change.

It is important to note that sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS did not change in this study based on condition. Previous research suggests that both sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS are associated with sexual assault in college. The use of sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS are associated with less incidence and severity of sexual assaults and less number of incapacitated attempted and completed rape. However, this intervention was ineffective at increasing the use of these PBS. In both sexual assault PBS and drinking PBS, the only significant predictors of use of PBS at the follow-up were baseline use of PBS. It may be that more personalized examinations of PBS is necessary, for example, it may be possible that participants did change which PBS that were used but it was not reflected in the average use of PBS. It may also be possible that providing individuals with a list of PBS that they currently use while providing others that they can use in the future is an ineffective way of changing use of PBS. Future research should examine how to effectively target the use of PBS for both sexual assault and drinking PBS given that both have been shown to be effective strategies of decreasing sexual assault risk and problematic alcohol use. Future research should also examine face-to-face deliveries of PBS for both alcohol use and sexual assault to determine if that is a more effective way to change PBS.

Previous research has suggested that alcohol use interventions can reduce incapacitated rape (Clinton-Sherrod et al., 2011; Testa et al., 2010), however, our findings did not support this. It may be because this was a web-based intervention and those that have found reductions were in person interventions. It may also be because sexual assault history was controlled for in the current study in two ways: participants were stratified to conditions based on sexual assault history and sexual assault history incidence and severity was controlled for in all of the analyses. Because sexual assault incidence and severity is so strongly associated with future sexual assaults, it is possible that if previous research controlled for sexual assault history, differences in treatment conditions may not exist. This needs to be assessed with future research.

Finally, this intervention program was not particularly effective for women with less severe sexual assault histories. It may be that women without a severe sexual assault history are at lower risk, and therefore, the number of assaults occurring within a 3-month time frame may be too low to find any significant change. It also may be possible that women with less severe sexual assault histories require a different type of intervention.

Limitations

Although the current study has many strengths, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. The first is that there are dosage differences, or length of intervention, among the conditions. Individuals who were in the full assessment only condition and the minimal assessment only condition did not receive any personalized information. Therefore, the time it took to participate was inherently less than if they were randomized to one of the personalized feedback interventions. Similarly, those who were assigned to the combined condition received twice as much information, making the time it took to participate inherently longer than those who were assigned to the alcohol only or SARR only conditions. This is potentially problematic given that differences in conditions may be due to dosage effects. However, despite the length of the intervention condition, it would be expected that targeting both alcohol use and sexual assault would likely still be the most effective intervention for high-risk women. This study is the first of its kind to target both alcohol use and sexual assault risk and future research should control for this discrepancy in conditions.

The current study includes only approximately 200 participants. Although this is a large sample size for the first study to determine if future research should examine the effects of these conditions further, these findings should be replicated using a larger sample. This is particularly necessary when examining low base rate events such as sexual assault victimization experiences in the past 3 months, with approximately one-fourth of the current sample reporting any sexual assault experience in the past 3 months.

Web-based interventions targeting alcohol use are effective at changing HED and drinking PBS with a small effect size. The current study only had power to detect a medium to large effect size, and it may be possible that a larger sample would yield significant differences. However, ideally, we’d like to be able to change these outcomes in a clinically significant way, even in smaller populations. In regards to PBS, it may be that a more fine tuned examination of changes is necessary. For example, rather than examining potential change in overall PBS, it is possible that participants did change use of particular PBS as a result of the intervention. Future studies examining PBS change could assess change in PBS in an idiographic way, which would allow for understanding if any new PBS were added into one’s repertoire as a result of the intervention or if they continued to use PBS they had engaged in prior to the intervention.

Participants in the study were recruited from Psychology courses and it is possible that these students differ in receptiveness to interventions like the one presented in the current study. The sample is also limited to students who are underage and engage in HED. The combined condition may not be applicable to students who are older and who do not engage in HED. Future research should include a random sample of college students to replicate the current findings. Additionally, these findings are limited to one university. It is possible that colleges and universities differ; thus, future research should include a multisite examination of the effectiveness of the current interventions. Participants were also not included or excluded based on their sexual orientation and future interventions should make interventions tailored based on specific issues associated with sexual orientation.

The results should also be interpreted with caution given that participants included in the analyses were those who completed the follow-up survey. It was found that those who completed the follow-up survey engaged in less drinking at baseline than those who did not complete the follow-up survey. A strength is that the completer analyses did include all participants whether or not they viewed the feedback.

Conclusions

Typically, interventions targeting sexual assault are ineffective in reducing sexual assault incidence when they are presented in a brief format and yet they are effective in changing cognitions (Vladutiu et al., 2011). The findings from this preliminary study suggest that web-based personalized feedback programs targeting sexual assault may be a more cost effective option for college campuses given that the combined condition reduces sexual assault risk among women with a sexual assault history compared to face-to-face risk reduction programs.

These preliminary results are exciting given that this is the first intervention to target both alcohol use and sexual assault risk in college women. It is interesting that the combined intervention was only effective in reducing sexual re-assault rates and not first sexual assault experiences. This combined web-based intervention could be easily disseminated in colleges to women with a sexual assault history to help reduce HED and sexual assaults among women at high risk of experiencing sexual assault in college.

Highlights.

We targeted alcohol use and sexual assault risk in college women

Web-based personalized feedback was used in the intervention conditions

Targeting both alcohol use and sexual assault risk reduced sexual re-victimization

Dissemination of this intervention is promising for college campuses

Acknowledgements

Data collection and manuscript preparation was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31AA020134) and a grant from the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington to the first author. This manuscript was written for partial completion of the first author’s dissertation. Thank you to all of the research assistants on the project and valuable feedback from the dissertation committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Koss MP. The effects of frame of reference on responses to questions about sexual assault victimization and perpetration. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 2005;29(4):364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, McAuslan P. Alcohol’s effects on sexual perception. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2000;61(5):688–697. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Whiston SC. Sexual assault education programs: A meta-analytic examination of their effectiveness. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 2005;29(4):374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbecher K. Sexual assault on college campuses: Is an ounce of prevention enough? Applied & Preventive Psychology. 2000;9(1):23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbecher K. The convergent validities of two measures of dating behaviors related to risk for sexual victimization. Journal Of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(8):1095–1107. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Criminal victimization in the United States, 2005 statistical tables: National crime victimization survey. US Department of Justice. 2006 (NCJ215244) [Google Scholar]

- Clinton-Sherrod M, Morgan-Lopez AA, Brown JM, McMillen BA, Cowells A. Incapacitated sexual violence involving alcohol among college women: The impact of a brief drinking intervention. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(1):135–154. doi: 10.1177/1077801210394272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Parks GA, Marlatt G. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2011;34(2):210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Gilmore AK, Stappenbeck CA, Balsan MJ, George WH, Norris J. How to score the sexual experiences survey? A comparison of nine methods. Journal of Violence. in press doi: 10.1037/a0037494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Farris C, Treat TA, Viken RJ. Alcohol alters men’s perceptual and decisional processing of women’s sexual interest. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:427–432. doi: 10.1037/a0019343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore KM. The social victims of drinking. British Journal of Addiction. 1985;80(3):307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1985.tb02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Lehman GL, Cue KL, Martinez LJ. Postdrinking sexual inferences: Evidence for linear rather than curvilinear dosage effects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:629–648. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Lynn S, Rich CL, Marioni NL, Loh C, Blackwell L, Pashdag J. The evaluation of a sexual assault risk reduction program: A multisite investigation. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1073–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, McNamara JR, Edwards KM. Women’s risk perception and sexual victimization: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Norberg KE, Bierut LJ. Binge drinking among youths and young adults in the United States: 1979–2006. Journal Of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(7):692–702. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a2b32f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KA, Gidycz CA. Evaluation of a sexual assault prevention program. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(6):1046–1052. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal Of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(6):419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(4):357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual experiences survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. The campus sexual assault (CSA) study. Department of Justice. 2007 (DOJ 221153) [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Patrick ME, Litt DM, Atkins DC, Kim T, Blayney JA, …Larimer ME. Randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-related risky sexual behavior among college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:429–440. doi: 10.1037/a0035550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2005;66(5):698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitka M. College binge drinking still on the rise. JAMA: Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2009;302(8):836–837. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Waterman CK. Predicting self-protection against sexual assault in dating relationships among heterosexual men and women, gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Journal Of College Student Development. 1999;40(2):132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, …Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Palmer RS, Larimer ME. Interest and participation in a college student alcohol intervention study as a function of typical drinking. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2004;65(6):736–740. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA (National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism) NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004;3:3. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, George WH, Stoner SA, Masters N, Zawacki T, Davis K. Women’s responses to sexual aggression: The effects of childhood trauma, alcohol, and prior relationship. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14(3):402–411. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Nurius PS, Dimeff LA. Through her eyes: Factors affecting women’s perception of and resistance to acquaintance sexual aggression threat. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 1996;20(1):123–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh YP, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Miller BA. Bar victimization of women. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 1997;21(4):509–525. [Google Scholar]

- Reed E, Amaro H, Matsumoto A, Kaysen D. The relation between interpersonal violence and substance use among a sample of university students: Examination of the role of victim and perpetrator substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CS, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner SA, Norris J, George WH, Davis K, Masters N, Hessler DM. Effects of alcohol intoxication and victimization history on women’s sexual assault resistance intentions: The role of secondary cognitive appraisals. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(4):344–356. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA, Turrisi R. Preventing college women’s sexual victimization through parent based intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science. 2010;11(3):308–318. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44(9–10):1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Collins R. The role of women’s alcohol consumption in evaluation of vulnerability to sexual aggression. Experimental And Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8(2):185–191. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Fu L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladutiu CJ, Martin SL, Macy RJ. College- or university-based sexual assault prevention programs: A review of program outcomes, characteristics, and recommendations. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2011;12(2):67–86. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]