Abstract

Bacteria have developed resistance against every antibiotic at an alarming rate, considering the timescale at which new antibiotics are developed. Thus, there is a critical need to use antibiotics more effectively, extend the shelf life of existing antibiotics, and minimize their side effects. This requires understanding the mechanisms underlying bacterial drug responses. Past studies have focused on survival in the presence of antibiotics by individual cells, as genetic mutants or persisters. In contrast, a population of bacterial cells can collectively survive antibiotic treatments lethal to individual cells. This tolerance can arise by diverse mechanisms, including resistance-conferring enzyme production, titration-mediated bistable growth inhibition, swarming, and inter-population interactions. These strategies can enable rapid population recovery after antibiotic treatment, and provide a time window for otherwise susceptible bacteria to acquire inheritable genetic resistance. Here, we emphasize the potential for targeting collective antibiotic tolerance behaviors as an antibacterial treatment strategy.

Introduction

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria have emerged as a global crisis, resulting in increased morbidity rates, mortality rates, and healthcare costs. The time interval between the introduction of a new antibiotic and the emergence of resistance has rapidly decreased since the 1930s, largely due to antibiotic overuse and misuse1. Concurrently, a lack of financial incentive has led pharmaceutical companies to decrease antibiotic research and development2. Given the drying antibiotic pipeline, it is critical to develop a detailed understanding of how bacteria survive antibiotic treatment. Doing so can uncover new treatment strategies and enable us to use existing antibiotics more effectively3.

Bacteria can survive antibiotics via many different mechanisms (Figure 1a). Genetic resistance can arise from de novo mutations or horizontal gene transfer4. Expression of resistance proteins can allow individual bacteria to survive antibiotic treatment by deactivating the antibiotic, altering the antibiotic’s target, or preventing its intracellular accumulation1, 4.

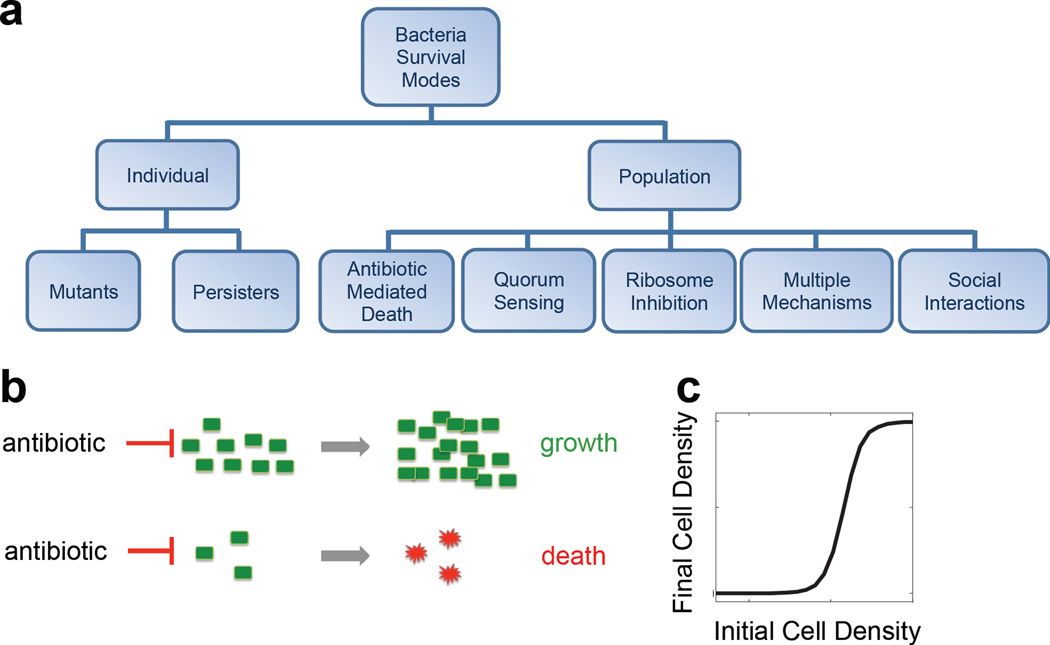

Figure 1. Bacterial survival modes.

a. Bacterial survival modes can be at the individual or population level. Populations can use different mechanisms to survive antibiotic collectively.

b. Collective antibiotic tolerance emerges when a population at a sufficiently high density can survive an antibiotic dose that would be lethal to a low density population.

c. Initial cell density determines the outcome of a population treated by an antibiotic. For each antibiotic concentration, there is a critical initial density above which the population will recover; below this, the population will die.

Bacteria can also exhibit phenotypic tolerance, whereby they survive antibiotic treatment without acquiring new mutations5. For example, a predominantly sensitive population often has a very small fraction of non- or slow-growing bacteria (persisters). These persisters may emerge stochastically, in response to stress, or due to errors in replication and cell metabolism6, 7. They are genetically identical to susceptible cells but are tolerant to antibiotics7, 8. In the absence of antibiotics, persisters can switch back to the growing state, leading to population recovery. As a result, persisters can cause post-treatment relapses and enable development of genetic resistance8. Unlike genetic resistance, persistence is non-inheritable, though the frequency of persisters in a population can be genetically determined8, 9.

In contrast, a population at a sufficiently high density can survive an antibiotic dose that is lethal to a low-density population (Figure 1b&c). This collective antibiotic tolerance (CAT) can arise from diverse mechanisms, including collective synthesis of resistance-conferring enzymes, antibiotic titration, and social interactions within and between populations10–12. CAT enables a population to recover faster than persisters, and provides a time window for otherwise susceptible bacteria to acquire genetic resistance12(Box 1, Figure 2). Here, we review mechanisms underlying CAT, their characteristic dynamics, and potential strategies to inhibit or exploit these mechanisms for antibacterial treatment.

Box 1.

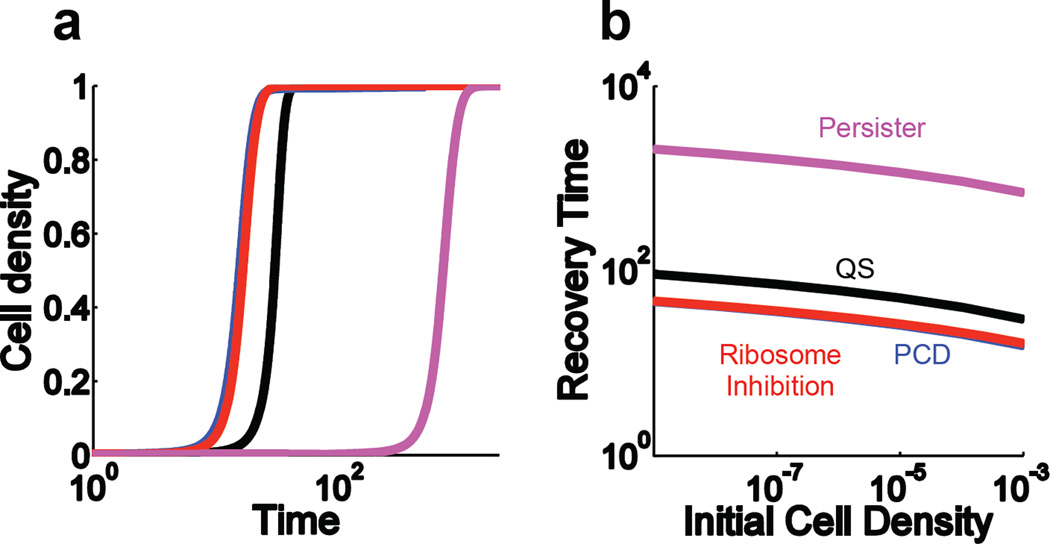

The mechanism by which bacteria survive antibiotic treatment can significantly influence the speed of their recovery. Here, we use previously published models to compare the recoveries of populations dependent on different forms of CAT or persistence9, 10, 24, 64. Figure 2a shows the three CAT populations recover significantly faster than the persister-dependent population. The recovery times decrease as the initial population density increases (Figure 2b). Populations surviving by enzyme-dependent CAT actively degrade antibiotic; thus, the antibiotic concentration is quickly reduced to sub-inhibitory levels, enabling recovery. In the case of bistable ribosome inhibition, at high cell densities, the intracellular antibiotic concentration is insufficient to overcome the positive feedback in ribosome synthesis, again leading to rapid recovery. Conversely recovery via persisters requires a relatively long time period due to the dependence on the slow, intrinsic removal of the antibiotic and the low frequency of persister formation.

Figure 2. [within Box 1]. Comparison of population level responses due to different forms of CAT or persistence.

a. Time course simulations. After being treated with an antibiotic, the bacteria actively tolerating antibiotics through bistable ribosome inhibition, PCD, or QS recover much faster than persisters.

b. Recovery times. For persisters and CAT bacteria alike, increasing the initial cell density decreases the time it takes for a population to recover from antibiotic treatment.

Mechanisms underlying CAT

Antibiotic-mediated altruistic death

Genetic antibiotic resistance arises from the expression of resistance-conferring proteins, which often degrade or modify the antibiotic4. However, expression levels of the resistance protein may be insufficient to provide single-cell level protection, depending on the antibiotic concentration. If so, the fate of a bacterial population will depend on its density (Figure 3a): population survival is determined by the relative rates of antibiotic-mediated killing and population-mediated antibiotic degradation. The population will initially decline due to antibiotic-mediated killing of some bacteria. This death is altruistic because the subsequent release of resistance proteins will benefit the surviving cells by contributing to antibiotic degradation13, 14. If the initial population density is too low, the population will be eradicated before the antibiotic is degraded to a sub-lethal level. Conversely, if the initial population density is sufficiently high, the total resistance protein can clear the antibiotic before complete eradication of the population, allowing the survivors to repopulate. The interplay between cell growth, antibiotic-mediated killing, and antibiotic degradation by the resistance protein from cells (live or dead) will result in CAT. Indeed, smaller inocula of pathogens expressing β-lactamases (Bla) are more susceptible to β-lactams than larger inocula15. Such CAT often arises from constitutive expression of Bla and other resistance proteins16. Alternatively, many pathogens’ Bla expression is up-regulated through the induction of ampC in the presence of β-lactam antibiotics16.

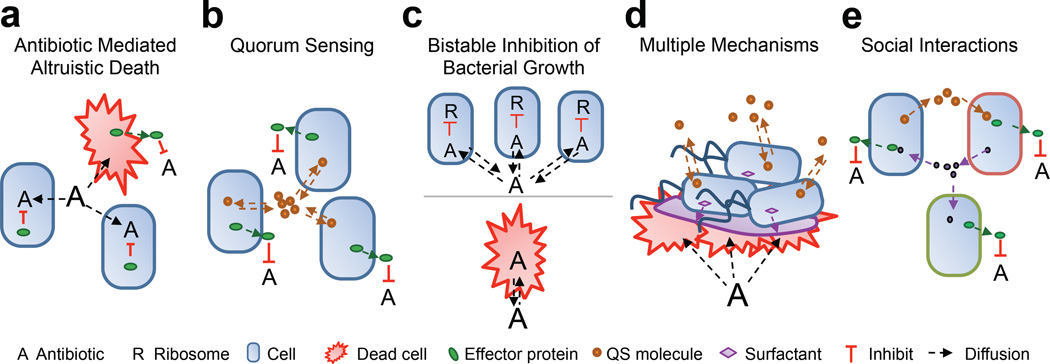

Figure 3. Underlying mechanisms of CAT.

a. Antibiotic mediated altruistic death involves a subpopulation lysing to release effector proteins that benefit the remainder of the population. CAT can only emerge if the population is large enough to generate a collective effector protein concentration sufficient to inhibit the antibiotic before the antibiotic kills all of the population.

b. Quorum sensing is often involved in regulating the expression of effector proteins or the maturation of biofilm formation, both of which can lead to CAT.

c. Bistable inhibition of bacterial growth arises as a function of intracellular antibiotic concentration and bistable ribosome inhibition. Sufficiently dense populations can titrate the antibiotic such that the intracellular concentration does not inhibit ribosome synthesis. However, low density populations cannot titrate the antibiotic to a sublethal level, thus, ribosome synthesis will be inhibited.

d. Multiple mechanisms can be used by a clonal population to survive antibiotic treatment. For example, swarming is a function of phenotype, QS, and PCD that confers antibiotic tolerance.

e. Social interactions can facilitate the survival of multiple subpopulations (denoted by different colored cell outlines). For instance, one subpopulation can produce a signaling molecule necessary to upregulate a second subpopulation’s resistance mechanism and vice versa. There are also situations where one subpopulation donates a signaling molecule that protects a second population, without deriving any benefit in return.

Partial population death is a natural consequence of bactericidal antibiotic action. In other contexts, antibiotic-mediated death is genetically programmed13. For example, some antibiotics affect bacterial death by interfering with toxin-antitoxin systems17. The mazEF system can result in programmed cell death (PCD) when an antibiotic, such as chloramphenicol, inhibits the transcription/translation of the MazE antitoxin18. Without the labile MazE antitoxin, the stable MazF toxin accumulates and triggers PCD. Other antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones, trigger PCD by inducing an SOS response19. During a stress response, PCD can benefit survivors by directly or indirectly relieving stress13, 14. When this occurs, the use of antibiotic can promote the survival of a pathogen and aggravate its virulence. For instance, antibiotics induce PCD in Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7. Encoded in a bacteriophage20, Stx is assembled and released upon cell lysis. Stx kills nearby eukaryotic predators, thereby enabling STEC growth and survival21. Death here is altruistic and required for the release of Stx. The population must be large enough to afford the cost of lysing the bacteria necessary to release sufficient Stx for survival.

Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation

If a resistance protein’s production is costly, it may be advantageous to delay synthesis until the cell density is high enough so the overall benefit of the protein outweighs its production cost. This delay can be realized by quorum sensing (QS), which enables bacteria to coordinate gene expression in a density-dependent manner22, 23. In QS, individual cells produce a signaling molecule that increases in extracellular concentration with cell density. By sensing the signal concentration, bacteria can coordinate gene expression according to their density22. Using a synthetic gene circuit, QS has been demonstrated to represent an optimal strategy for controlling the expression of a costly protein that benefits the entire population24.

QS could control the expression of resistance-conferring enzymes (Figure 3b). In Providencia stuartii, a Gram-negative pathogen that causes urinary catheter infections, QS controls the expression of an acetyltransferase, which inactivates aminoglycoside antibiotics25,26. Low-density populations express minimal levels of acetyltransferase, rendering them sensitive to aminoglycosides; high cell density triggers acetyltransferase expression, yielding CAT.

QS can also contribute to CAT by modulating biofilm formation, which enhances antibiotic tolerance27. Although the specifics of biofilm formation vary by species, the general steps are similar23, 28. Planktonic bacteria first attach to a surface at a low density and begin to form microcolonies, while producing basal levels of QS signals. Once the population reaches a sufficiently high density, the accumulated QS signals activate genes involved in biofilm formation22. Depending on the antibiotic and bacterial specie, the surface layer of biofilms may serve as a protective barrier for resident bacteria by reducing the penetration rate of some antibiotics29, 30. Moreover, some antibiotics, such as piperacillin or ampicillin, can induce antibiotic-deactivating enzymes in biofilms, which can further reduce antibiotic penetration and the killing of biofilmresiding bacteria31, 32. Biofilms also have limited nutrients at their core, which diminishes internal cell growth. These slow growing cells tend to be less sensitive to certain antibiotics33.

Bistable inhibition of the replication machinery

When bacterial populations produce a resistance-conferring protein, density-dependence may be intuitive: increasing cell density increases total protein production, thus increasing the likelihood that a population will survive treatment34. However, CAT has also been observed in response to antibiotics that inhibit ribosome activity and protein synthesis (e.g. gentamicin) without requiring production of degrading enzymes35.

A previous study has established a mechanism for CAT in the absence of active antibiotic degradation: intra-population antibiotic titration coupled with bistable ribosome inhibition10 (Figure 3c). In each cell, ribosome synthesis is controlled by positive feedback: ribosomes translate mRNA into proteins, including ribosome components, resulting in ribosome synthesis36. This feedback can be inhibited by intracellular antibiotic, resulting in a bistable response37.

Within a population, the extracellular antibiotic is allocated to individual cells according to the import and export rates across the cell membrane. When import is faster than export, the intracellular antibiotic will be higher than the extracellular concentration, and will decrease slightly with increasing cell density. This decrease is amplified by ribosomal positive feedback, leading to bistable growth inhibition: at high cell densities, the average intracellular antibiotic concentration is relatively low (below minimum inhibitory concentrations), positive feedback overcomes antibiotic inhibition and enables population survival. Modeling suggests that density dependence can be modulated by altering various processes, such as drug uptake and binding. However, the critical condition required for CAT in this scenario is the rapid degradation of ribosomes, which can be triggered by antibiotics that target ribosomal components. These antibiotics induce heat-shock response38, which leads to upregulation of proteases and faster degradation of ribosomal components39. If the ribosome degradation rate remains slow, as with chloramphenicol treatment, the population fate is density-independent: populations either grow (low antibiotic concentrations) or die (high antibiotic concentrations). When coupled with direct induction of heat shock, however, these antibiotics can also cause bistable inhibition of population growth, leading to CAT.

Mixed strategies

In nature, CAT often arises from traits that are controlled by combinations of the mechanisms discussed above. For example, when PCD is coupled with density-dependent gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus, lysis is tightly controlled and can result in CAT through biofilm formation. CidA and LrgA expressions turn lysis ON and OFF at specified stages of cell growth, respectively40. Lysis releases genomic DNA, resulting in enhanced biofilm formation41, 42. These genes have been linked to regulation of antibiotic tolerance: mutations disrupting CidA or LrgA enhance or reduce population survival, respectively40, 43.

Another strategy to survive antibiotic treatment involves a combination of phenotypically shifting from a "swimming" state (planktonic growth) to a “swarming” state (surface growth), QS, and altruistic death (Figure 3d). Swarming is flagella-driven group-migration of bacteria over a semi-solid surface and happens exclusively at the leading edge of a population44, 45. Although the underlying mechanisms are species dependent and not fully elucidated, some swarming species have been observed to rely on QS to upregulate the production of biosurfactants, such as rhamnolipids, which are necessary for reducing surface tension44. Swarmers exhibit increased tolerance to a variety of antibiotics, including aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones45, 46. Altruistic death may contribute to this survival advantage. It is speculated that cells dying from prolonged direct contact with the antibiotic form a protective platform that prevents other swarmers from coming into direct contact45. Thus, the population has to have a high enough density to upregulate QS-mediated swarming genes45 and afford the cost of individuals that are directly exposed to the antibiotic. While swarming and biofilm formation involve similar mechanisms, such as altruistic death and QS, the two states are inversely regulated47, 48. As a result, biofilms contain a population of sessile cells while swarms disperse a population of active cells48.

The mechanisms underlying swarming-mediated motility and density-dependent survival appear to vary between species; QS has been implicated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa44, but not in Salmonella45. Other studies have examined the impact of biofilm creation45 and increased efflux pump expression49. Swarming motility has been observed to strongly correlate with the expression of the pmrHFIJKLM operon46. This operon encodes the lipid A portion of LPS, which reduces the binding strength of various antimicrobial peptides50. A previous study shows pmrK expression is upregulated in conditions that promote swarming. Expression decreases as cells dedifferentiate from the swarming phenotype, and knockout results in the loss of swarming ability46.

Social interactions

In a mixed population, CAT can be facilitated by “charitable” actions, wherein one subpopulation produces a product that helps another subpopulation, without receiving any benefit from the latter (Figure 3e). For example, a recent study demonstrated how a population of drug sensitive E. coli can tolerate antibiotic with the aid of a few highly resistant population members51. In the absence of antibiotic, the entire population produces indole, a signaling molecule generated by growing bacteria. In the presence of an antibiotic, however, only a subpopulation with mutated efflux pumps has the resistance necessary to continue producing large amounts of indole. The released indole upregulates efflux pump expression and oxidative-stress mechanisms, thus enabling the entire population to tolerate the antibiotic. This survival tactic will fail if the fraction of mutant indole producers is too small to support a large population of sensitive cells or if the metabolic cost of production is too high.

CAT can also arise from mutualistic interactions, where two or more bacterial populations depend on one another to survive. For instance, an engineered system can demonstrate how two populations can collaborate to survive different antibiotics12. Each engineered population produced the QS signal molecule needed by the other to upregulate the production of a resistance protein. Increasing either population’s initial density increased QS signal accumulation, resulting in higher final densities following antibiotic treatment.

Similarly, multispecies swarms can arise due to the communal nature of QS signals. For example, Serratia ficaria do not produce biosurfactants, but they do produce QS signals necessary for S. liquefaciens QS-deficient mutants to upregulate their own biosurfactant production. Once sufficient signaling molecules accumulate, S. liquefaciens’ biosurfactant production facilitates the swarming52 and, presumably, the CAT of both populations.

Another example of mutualism-mediated CAT can be found in multi-species biofilms53. For example, species can work together to decrease antibiotic penetration of biofilms. Burkhodia cepacia and P. aeruginosa, both associated with cystic fibrosis, produce polysaccharides that interact to increase biofilm viscosity and decrease antibiotic activity54.

Implications for antimicrobial treatment strategies

The diverse mechanisms underlying CAT have implications for developing new treatment strategies. In particular, different mechanisms can lead to unique population and evolutionary dynamics that can be exploited for better treatment efficacy or serve as a cautionary tale against simplistic treatment strategies.

Timing in antibiotic dosing

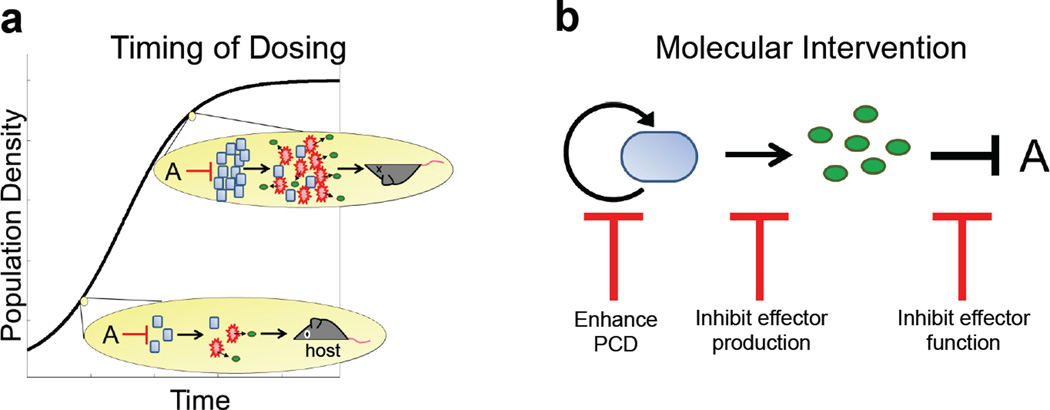

A common property of CAT mechanisms is that a bacterial population is most vulnerable at low densities. This suggests the potential to inhibit bacterial growth by controlling the timing of antibiotic doses. One method would be to detect and treat infections at earlier stages of development, when insufficient bacteria are present to realize CAT (Figure 4a). A mouse study on treating STEC infections showed early treatment (1–3 days after infection) with a lysis-inducing antibiotic resulted in zero mortality, while late treatment (3–5 days) resulted in 95% mortality55. The improved outcome by early treatment may have resulted from suppression of bacterial growth or virulence factor production. Targeting early stage infections is also effective in treating biofilms; studies have demonstrated that immature biofilms are more susceptible to antibiotic treatment56, 57.

Figure 4. Inhibition strategies.

a. Timing control of antibiotic dosing is critical for optimizing efficacy of periodic antibiotic treatments. By timing the application of antibiotic doses with when the population is at a low density, the amount of public good and/or toxin released would be insufficient to allow the population to recover or harm the host.

b. Molecular-level interventions of CAT could be used to trigger PCD and inhibit the production and/or the function of an effector protein.

Timing control is intrinsic in the design of periodic antibiotic dosing protocols, which can be determined by the dynamic response of a population exhibiting CAT. A previous study demonstrated that different periodic dosing frequencies have drastically different outcomes when treating a population capable of generating CAT due to bistable ribosome inhibition10. When antibiotic doses were delivered at high frequency, populations had insufficient time to recover. Conversely, when doses were delivered at low frequency, the antibiotic eradicated the population to such an extent that it could not recover. For intermediate frequencies, however, treatment was ineffective; populations recovered between doses. Furthermore, the frequency range over which populations were able to survive can be modulated by changing the fraction of each period spent at a high antibiotic concentration. In general, the optimal dosing protocol will likely depend on the specific types of mechanisms by which CAT arises, representing a significant direction for quantitative biology research.

Molecular interventions to Disrupt CAT

Different mechanisms underlying CAT also suggest potential targets for molecular-level intervention (Figure 4b). CAT facilitated by enzyme expression can be reduced by inhibiting either the production or the action of the enzyme. These strategies are often adopted for treating bacteria that produce Bla. Weak inducers of AmpC Bla production, e.g. cefepimes and piperacillin, have been shown to have lower MICs when treating inducible pathogens58. Alternatively, a Bla-inhibitor, such as clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam, is frequently used in conjuction with a β-lactam antibiotic to treat Bla-producing bacteria59. It should be noted that some bacteria have already evolved resistant mechanisms to Bla inhibitors60.

This strategy can also be applied to target CAT resulting from PCD. Studies have begun to screen antimicrobial peptides that have increased efficacy in activating killing by triggering bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems61, 62. For some pathogens, however, activation of PCD alone may be undesirable as it can enhance bacterial survival and virulence. Instead, PCD inhibition can reduce virulence by suppressing the release of effectors that promote bacterial survival or virulence. For example, in Streptococcus pneumoniae, release of a virulence factor to extracellular space is mediated by autolysis of a subpopulation of cells63, which in turn can benefit survivors. Serum from mice immunized with autolysin inhibited autolysis and reduced bacterial virulence63. It will be interesting to examine how such strategies will impact overall bacterial survival. As demonstrated using synthetic gene circuits64, reduced lysis can paradoxically lead to overall worse bacterial survival.

Similar strategies that inhibit either the production or the action of an enzyme have been applied to target QS pathogens. Targeting QS is appealing as it can reduce virulence without directly targeting the immediate survival of cells. For example, azithromycin has been shown to inhibit QS signaling, leading to inhibition of biofilm formation and virulence in P. aeruginosa65,66. Likewise, enzymes, such as AiiA that hydrolyze QS signal molecules67 and synthetic molecules that prevent AHL receptor activation68, can also block QS signaling and lead to decreased virulence and increased susceptibility to antibiotic treatment in QS pathogens69. Drugs that target the function of QS-mediated proteins have also been studied. Oseltamivir is a drug originally developed to inhibit viral production of neuraminidase. As neuraminidase is also a QS-mediated enzyme essential for P. aeruginosa’s initial colonization process and subsequent biofilm formation, oseltamivir has been tested for its ability to inhibit biofilm formation. Indeed, a dose-dependent decrease in biofilm formation was observed when oseltamivir was applied70.

Rapid ribosome turnover is a prerequisite to generate CAT against antibiotics that target ribosomes10. As the rate of ribosome turnover increases, the range of antibiotic concentrations over which CAT occurs shrinks and shifts towards lower values. To reduce or eliminate CAT, future drug development could focus on alternative avenues to disrupt ribosome efficacy, such as interfering with subunit assembly71. Targeting pathways involved in the stringent response could also eliminate CAT. In response to various stresses, many bacterial species reduce rRNA transcription and ribosome synthesis while up-regulating amino acid synthesis72. These metabolic shifts can promote bacterial survival and virulence73. Inhibition of such metabolic shifts could prevent CAT at high population densities. These pathways may thus represent potential targets for new drugs74.

A prior study observed that a fundamental requirement for swarming is the production of extracellular surfactants, particularly lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which lubricate cells’ local environment so they can “slide” past each other46. Therefore, the increased antibiotic tolerance exhibited by swarmers could be avoided by inhibiting LPS production75. Previous studies have shown that LPS inhibition by antimicrobial peptides results in the loss of swarming motility50. A caveat is that inhibiting swarming motility could lead to increased biofilm formation76, as these phenotypes are often linked.

Finally, mixed populations can be inhibited by targeting the keystone members. In the case of charitable interactions, treatments should target the subpopulation producing the resistant protein that protects producers and non-producers alike. For instance, penicillin treatment of tonsillitis is often ineffective due to mixed populations of Bla producing pathogens that protect Streptococci. However, the infections were effectively treated upon the introduction of a Bla inhibitor, clavulanic acid77. In a mutual relationship, such as in the aforementioned synthetic system12, survival depends on both subpopulations being present. For such systems, a viable treatment strategy could be to disable one subpopulation such that all participating subpopulations are more susceptible to treatment. To this end, Clustered Regulatory Interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas systems could represent an ideal antimicrobial strategy to directly target the specific sub-populations that promote CAT. This genome-editing tool utilizes targeted guide RNA sequences that can be designed to recognize desired bacterial DNA and induce nucleic acid breaks, which can disrupt gene function in the target. Indeed, recent studies demonstrate the ability to customize antimicrobial treatments by the targeted inactivation or killing of specific bacteria within a population through CRISPR delivery78, 79.

Treatment Considerations

Depending on the underlying mechanisms, complex treatment responses could arise from populations capable of CAT. One counterintuitive response is the Eagle effect, a phenomenon wherein increasing antibiotic concentration promotes bacterial recovery80. Whether and to what extent the Eagle effect happens in the clinical setting remains to be tested; however, the Eagle effect has been observed to result from PCDmediated tolerance in vitro64.

Another example is the counterintuitive effect of inhibiting different aspects of QS. Inhibiting QS signal synthesis effectively increases the cell density threshold required to trigger downstream gene expression, such as virulence factor production81. However, QS inhibition also alleviates the metabolic burden placed on each cell, resulting in faster growth24. Despite this caveat, the overall outcome of QS signaling inhibition ultimately depends on bacterial survival and virulence development. The treatment would likely be considered successful if the target bacteria are rendered non-pathogenic82.

While QS inhibition can attenuate virulence in the short term, it can promote the selection of more virulent pathogens in the long term83. For example, long-term inhibition of QS signaling in P. aeruginosa by azithromycin can select for more cooperative and virulent individuals66, 83. Azithromycin inhibits general protein synthesis; however, it has been shown that QS-regulated genes are among the most severely inhibited by this drug84. Over an 11 day course of azithromycin in patients, a slight decrease in the frequency of QS-deficient mutants was observed; the QS-deficient mutant frequency in the placebo group increased approximately 2-fold83. One possible explanation for this counterintuitive response is, when uninhibited, the cooperative nature of QS is prone to cheaters: cells that do not produce virulence factors exploit the benefit while avoiding the cost of public good production85. Cheaters, therefore, are less virulent, but have a fitness advantage. For instance, P. aeruginosa cheaters that are QS-deficient due to LasR mutations have a growth advantage over the wildtype66, 86. When the QS signal is inhibited and no public goods are synthesized, the fitness advantage by the cheaters will be reduced, making it more difficult for them to outcompete cooperators. The negative consequences of direct inhibition of enzyme production may be avoided by inhibiting the enzyme after it is produced87. This strategy aims to maintain the cost of enzyme production while eliminating the benefits, leaving virulent bacteria at a metabolic disadvantage and more vulnerable to treatment. This method may also reduce the selective pressure induced by antibiotic treatment, slowing pathogens’ adaptive response.

Although resistance has been well studied, predicting long term consequences on bacterial dynamics has proved elusive. Bacteria have already developed strategies to survive QS inhibition83 and combination treatments involving Bla inhibitors60 and will likely develop strategies to survive other inhibition methods. A better understanding of bacterial population and evolutionary dynamics under different treatment strategies can help us optimize treatment strategy. More quantitative studies are needed to better establish the evolutionary dynamics involved in QS-mediated cooperation and the impact of inhibition on different aspects of QS. For instance, the discussion above only considers QS effectors that are public goods. The evolutionary outcomes can be significantly different if the effectors are private goods, which only benefit the cell that produces them,88 or species-specific goods, which only benefit a particular population of cells89. The same challenge is applicable for the population and evolutionary dynamics of other mechanisms leading to CAT. To this end, the use of well-defined model systems90, both natural10, 88, 91, 92 and engineered24, 64, 89, will be valuable for the development of better quantitative understanding of a population’s response to antibiotics. This understanding can serve as the critical foundation to design ‘evolution proof’ treatment strategies that select against resistance93.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Related research in our lab is in part funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. HRM acknowledges the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, JKS acknowledges a Duke Center for Biomolecular and Tissue Engineering graduate fellowship.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Levy SB, Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nature medicine. 2004;10:S122–S129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Projan SJ. Why is big Pharma getting out of antibacterial drug discovery? Current opinion in microbiology. 2003;6:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishman N. Antimicrobial stewardship. American journal of infection control. 2006;34:S55–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;74:417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuomanen E, Durack D, Tomasz A. Antibiotic tolerance among clinical isolates of bacteria. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1986;30:521. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2006;5:48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson PJ, Levin BR. Pharmacodynamics, population dynamics, and the evolution of persistence in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003123. This study demonstrates that persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus can be modulated by sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations. The authors argue that persistence can arise as the result of replication errors and variation in metabolic activity, as opposed to being an evolved characteristic.

- 8.Levin BR, Rozen DE. Non-inherited antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2006;4:556–562. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 2004;305:1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. This study uses microfluidics to examine growth rate differences between persistent and proliferative cells. The authors demonstrate the emergence to two classes of persisters: those that are non-growing at stationary phase, and those that are formed by spontaneous switching from a proliferative state during exponential growth.

- 10. Tan C, et al. The inoculum effect and band-pass bacterial response to periodic antibiotic treatment. Molecular systems biology. 2012;8 doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.49. Integrating mathematical modeling and experiments, the authors show that antibiotics that inhibit bacterial replication machinery and induce a heat shock response can result in density-dependent population survival. Furthermore, they demonstrate that periodic dosing can lead to a bandpass filtering response, wherein populations can survive under intermediate dosing frequencies.

- 11.Lee JH, Lee J. Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2010;34:426–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu B, Du J, Zou R-y, Yuan Y-j. An environment-sensitive synthetic microbial ecosystem. PloS one. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010619. This manuscript uses a synthetic system to show how mutualism can result in collective antibiotic tolerance. Individually, the bacterial strains would be sensitive to an antibiotic; however, when they are together, they upregulate each other’s antibiotic tolerance mechanisms.

- 13.Tanouchi Y, Lee AJ, Meredith H, You L. Programmed cell death in bacteria and implications for antibiotic therapy. Trends in microbiology. 2013;21:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nedelcu AM, Driscoll WW, Durand PM, Herron MD, Rashidi A. On the paradigm of altruistic suicide in the unicellular world. Evolution. 2011;65:3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomson KS, Moland ES. Cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam, and the inoculum effect in tests with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2001;45:3548–3554. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3548-3554.2001. This study investigates the efficacy of several β-lactam antibiotics against various extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing strains. The authors found that higher inocula exhibited at least an 8-fold higher MIC for the drugs tested, implying that β-lactamase production can be a mechanism for density-dependent survival.

- 16.Sykes R, Matthew M. The β-lactamases of gram-negative bacteria and their role in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1976;2:115–157. doi: 10.1093/jac/2.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolodkin-Gal I, Sat B, Keshet A, Engelberg-Kulka H. The communication factor EDF and the toxin–antitoxin module mazEF determine the mode of action of antibiotics. PLoS biology. 2008;6:e319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelberg-Kulka H, Sat B, Reches M, Amitai S, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death systems as targets for antibiotics. Trends in microbiology. 2004;12:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGannon CM, Fuller CA, Weiss AA. Different classes of antibiotics differentially influence Shiga toxin production. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2010;54:3790–3798. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01783-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plunkett G, Rose DJ, Durfee TJ, Blattner FR. Sequence of Shiga Toxin 2 Phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157: H7: Shiga Toxin as a Phage Late-Gene Product. Journal of bacteriology. 1999;181:1767–1778. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1767-1778.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lainhart W, Stolfa G, Koudelka GB. Shiga toxin as a bacterial defense against a eukaryotic predator, Tetrahymena thermophila. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191:5116–5122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00508-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annual Reviews in Microbiology. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Molecular microbiology. 2003;50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai A, Tanouchi Y, You L. Optimality and robustness in quorum sensing (QS)-mediated regulation of a costly public good enzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:19810–19815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211072109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robicsek A, et al. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nature medicine. 2005;12:83–88. doi: 10.1038/nm1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding X, Baca-DeLancey RR, Rather PN. Role of SspA in the density-dependent expression of the transcriptional activator AarP in Providencia stuartii. FEMS microbiology letters. 2001;196:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Juhas M, Eberl L, Tümmler B. Quorum sensing: the power of cooperation in the world of Pseudomonas. Environmental microbiology. 2005;7:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00769.x. This review discusses the role of quorum sensing in P. aeruginosa virulence, particularly the coupled Las and Rhl motifs. The authors also discuss the potential of interfering with quorum sensing systems as an antimicrobial strategy.

- 28.Davies DG, et al. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishida H, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of levofloxacin against biofilm-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1998;42:1641–1645. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh R, Ray P, Das A, Sharma M. Penetration of antibiotics through Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2010;65:1955–1958. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderl JN, Franklin MJ, Stewart PS. Role of antibiotic penetration limitation in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm resistance to ampicillin and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2000;44:1818–1824. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1818-1824.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giwercman B, Jensen E, Høiby N, Kharazmi A, Costerton J. Induction of beta-lactamase production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1991;35:1008–1010. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.5.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costerton J, Stewart PS, Greenberg E. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Craig WA, Bhavnani SM, Ambrose PG. The inoculum effect: fact or artifact? Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2004;50:229–230. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Udekwu KI, Parrish N, Ankomah P, Baquero F, Levin BR. Functional relationship between bacterial cell density and the efficacy of antibiotics. Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2009;63:745–757. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tadmor AD, Tlusty T. A coarse-grained biophysical model of E. coli and its application to perturbation of the rRNA operon copy number. PLoS computational biology. 2008;4:e1000038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thron C. Bistable biochemical switching and the control of the events of the cell cycle. Nonlinear Analysis: Theory, Methods & Applications. 1997;30:1825–1834. [Google Scholar]

- 38.VanBogelen RA, Neidhardt FC. Ribosomes as sensors of heat and cold shock in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1990;87:5589–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sykes MT, Shajani Z, Sperling E, Beck AH, Williamson JR. Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Ribosome Assembly and Turnover <i>In Vivo</i>. Journal of molecular biology. 2010;403:331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rice KC, et al. The Staphylococcus aureus cidAB operon: evaluation of its role in regulation of murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:2635–2643. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2635-2643.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice KC, et al. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:8113–8118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayles KW. The biological role of death and lysis in biofilm development. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groicher KH, Firek BA, Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:1794–1801. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1794-1801.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Köhler T, Curty LK, Barja F, van Delden C, Pechère J-C. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:5990–5996. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.5990-5996.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Butler MT, Wang Q, Harshey RM. Cell density and mobility protect swarming bacteria against antibiotics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:3776–3781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910934107. This work shows that a swarming phenotype promotes bacterial survival of antibiotic treatment. They demonstrate that this survival advantage is not due to quorum sensing or induced resistance pathways, but rather at a cost to cells directly exposed to antibiotic.

- 46.Kim W, Killam T, Sood V, Surette MG. Swarm-cell differentiation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in elevated resistance to multiple antibiotics. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:3111–3117. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.10.3111-3117.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verstraeten N, et al. Living on a surface: swarming and biofilm formation. Trends in microbiology. 2008;16:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Ditmarsch D, et al. Convergent evolution of hyperswarming leads to impaired biofilm formation in pathogenic bacteria. Cell reports. 2013;4:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.026. This study shows that a swarming phenotype is inversely correlated with biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa, suggesting an evolutionary tradeoff between these two mechanisms of antibiotic tolerance.

- 49.Overhage J, Bains M, Brazas MD, Hancock RE. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a complex adaptation leading to increased production of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:2671–2679. doi: 10.1128/JB.01659-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunn JS. Bacterial modification of LPS and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Journal of endotoxin research. 2001;7:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee HH, Molla MN, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Bacterial charity work leads to population-wide resistance. Nature. 2010;467:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature09354. This study demonstrates how collective tolerance can arise in a mixed population. Specifically, a population largely consisting of antibiotic-sensitive bacteria can survive treatment if a fraction of the population is resistant mutants that produce enough signaling molecule for the entire population to increase tolerance.

- 52.Andersen JB, et al. gfp-based N-acyl homoserine-lactone sensor systems for detection of bacterial communication. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2001;67:575–585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.575-585.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moons P, Michiels CW, Aertsen A. Bacterial interactions in biofilms. Critical reviews in microbiology. 2009;35:157–168. doi: 10.1080/10408410902809431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allison D, Matthews M. Effect of polysaccharide interactions on antibiotic susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of applied bacteriology. 1992;73:484–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb05009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurioka T, Yunou Y, Harada H, Kita E. Efficacy of antibiotic therapy for infection with Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157: H7 in mice with protein-calorie malnutrition. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 1999;18:561–571. doi: 10.1007/s100960050348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumon H, Ono N, Iida M, Nickel JC. Combination effect of fosfomycin and ofloxacin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa growing in a biofilm. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1995;39:1038–1044. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schultz G, Phillips P, Yang Q, Stewart P. Biofilm maturity studies indicate sharp debridement opens a time-dependent therapeutic window. Journal of wound care. 2010;19:320. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.8.77709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacoby GA. AmpC β-lactamases. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2009;22:161–182. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Drawz SM, Bonomo RA. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2010;23:160–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00037-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chaibi E, Sirot D, Paul G, Labia R. Inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases: phenotypic, genetic and biochemical characteristics. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1999;43:447–458. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mutschler H, Meinhart A. ε/ζ systems: their role in resistance, virulence, and their potential for antibiotic development. Journal of molecular medicine. 2011;89:1183–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0797-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lioy VS, Rey O, Balsa D, Pellicer T, Alonso JC. A toxin–antitoxin module as a target for antimicrobial development. Plasmid. 2010;63:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berry AM, Lock RA, Hansman D, Paton JC. Contribution of autolysin to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infection and immunity. 1989;57:2324–2330. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2324-2330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tanouchi Y, Pai A, Buchler NE, You L. Programming stress-induced altruistic death in engineered bacteria. Molecular systems biology. 2012;8 doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.57. This study uses a synthetic system to demonstrate the conditions under which programmed cell death can benefit a population. In particular, a population has to be producing sufficient amounts of a public good (such as β-lactamase) to benefit from lysing; otherwise the population will go extinct.

- 65.Tateda K, et al. Azithromycin inhibits quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2001;45:1930–1933. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.6.1930-1933.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Delden C, et al. Azithromycin to prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia by inhibition of quorum sensing: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive care medicine. 2012;38:1118–1125. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong Y-H, Xu J-L, Li X-Z, Zhang L-H. AiiA, an enzyme that inactivates the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal and attenuates the virulence of Erwinia carotovora. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:3526–3531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060023897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O’Loughlin CT, et al. A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:17981–17986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316981110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brackman G, Cos P, Maes L, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Quorum sensing inhibitors increase the susceptibility of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011;55:2655–2661. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Soong G, et al. Bacterial neuraminidase facilitates mucosal infection by participating in biofilm production. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2297–2305. doi: 10.1172/JCI27920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehta R, Champney WS. 30S ribosomal subunit assembly is a target for inhibition by aminoglycosides in Escherichia coli. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2002;46:1546–1549. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1546-1549.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maisonneuve E, Gerdes K. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Bacterial Persisters. Cell. 2014;157:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dalebroux ZD, Svensson SL, Gaynor EC, Swanson MS. ppGpp Conjures Bacterial Virulence. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;74:171–199. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A Common Mechanism of Cellular Death Induced by Bactericidal Antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toguchi A, Siano M, Burkart M, Harshey RM. Genetics of swarming motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: critical role for lipopolysaccharide. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:6308–6321. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.22.6308-6321.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mireles JR, Toguchi A, Harshey RM. Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Swarming Mutants with Altered Biofilm-Forming Abilities: Surfactin Inhibits Biofilm Formation. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:5848–5854. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5848-5854.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brook I, Pazzaglia G, Coolbaugh JC, Walker RI. In-vivo protection of group A β-haemolytic streptococci from penicillin by β-lactamase-producing Bacteroides species. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1983;12:599–606. doi: 10.1093/jac/12.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Citorik RJ, Mimee M, Lu TK. Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases. Nature biotechnology. 2014:1141–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bikard D, et al. Exploiting CRISPR-Cas nucleases to produce sequence-specific antimicrobials. Nature biotechnology. 2014:1146–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eagle H, Musselman AD. The rate of bactericidal action of penicillin in vitro as a function of its concentration, and its paradoxically reduced activity at high concentrations against certain organisms. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1948;88:99–131. doi: 10.1084/jem.88.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hentzer M, et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hentzer M, Givskov M. Pharmacological inhibition of quorum sensing for the treatment of chronic bacterial infections. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:1300–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Köhler T, Perron GG, Buckling A, Van Delden C. Quorum sensing inhibition selects for virulence and cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000883. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000883. This work presents clinical evidence that inhibiting quorum sensing counterintuitively selects for virulent pathogens in the long term.

- 84.Nalca Y, et al. Quorum-sensing antagonistic activities of azithromycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: a global approach. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2006;50:1680–1688. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1680-1688.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schuster M, Joseph Sexton D, Diggle SP, Peter Greenberg E. Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing: from evolution to application. Annual review of microbiology. 2013;67:43–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sandoz KM, Mitzimberg SM, Schuster M. Social cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:15876–15881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.André JB, Godelle B. Multicellular organization in bacteria as a target for drug therapy. Ecology Letters. 2005;8:800–810. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dandekar AA, Chugani S, Greenberg EP. Bacterial quorum sensing and metabolic incentives to cooperate. Science. 2012;338:264–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1227289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chuang JS, Rivoire O, Leibler S. Simpson's paradox in a synthetic microbial system. Science. 2009;323:272–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1166739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tanouchi Y, Smith RP, You L. Engineering microbial systems to explore ecological and evolutionary dynamics. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2012;23:791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Darch SE, West SA, Winzer K, Diggle SP. Density-dependent fitness benefits in quorum-sensing bacterial populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:8259–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118131109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yurtsev EA, Chao HX, Datta MS, Artemova T, Gore J. Bacterial cheating drives the population dynamics of cooperative antibiotic resistance plasmids. Molecular systems biology. 2013;9 doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Allen RC, Popat R, Diggle SP, Brown SP. Targeting virulence: can we make evolution-proof drugs? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2014;12:300–308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3232. This review highlights some of the counterintuitive outcomes of antivirulence antibiotic treatments and discusses whether or not it is possible to prevent resistant mechanisms from arising.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.