Abstract

Ethylene glycol (EG) and methanol are responsible for life-threatening poisonings. Fomepizole, a potent alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) inhibitor, is an efficient and safe antidote that prevents or reduces toxic EG and methanol metabolism. Although no study has compared its efficacy with ethanol, fomepizole is recommended as a first-line antidote. Treatment should be started as soon as possible, based on history and initial findings including anion gap metabolic acidosis, while awaiting measurement of alcohol concentration. Administration is easy (15 mg/kg-loading dose, either intravenously or orally, independent of alcohol concentration, followed by intermittent 10 mg/kg-doses every 12 hours until alcohol concentrations are <30 mg/dL). There is no need to monitor fomepizole concentrations. Administered early, fomepizole prevents EG-related renal failure and methanol-related visual and neurological injuries. When administered prior to the onset of significant acidosis or organ injury, fomepizole may obviate the need for hemodialysis. When dialysis is indicated, 1 mg/kg/h-continuous infusion should be provided to compensate for its elimination. Side-effects are rarely serious and with a lower occurrence than ethanol. Fomepizole is contraindicated in case of allergy to pyrazoles. It is both efficacious and safe in the pediatric population, but is not recommended during pregnancy. In conclusion, fomepizole is an effective and safe first-line antidote for EG and methanol intoxications.

Keywords: ethanol, hemodialysis, metabolic acidosis

Introduction

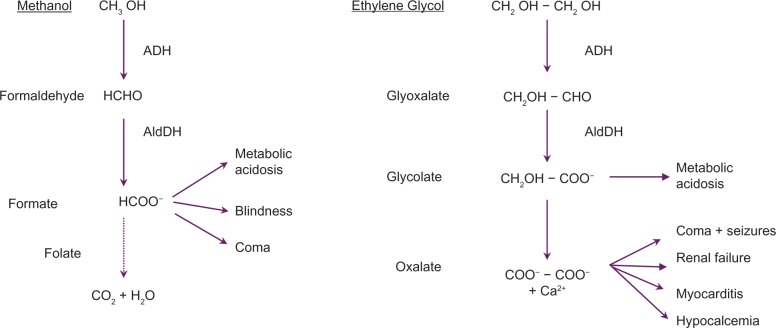

Although relatively uncommon, ethylene glycol (EG) and methanol poisonings remain important causes of suicide and epidemic poisonings, resulting in multiple deaths and serious sequelae.1–4 In 2008, the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System reported 922 cases of EG and 825 cases of methanol exposures resulting in a total of 20 deaths.1 However, this undoubtedly underestimated the real number of cases.5 Poisonings may occur through self-harm, misuse, or potentially malicious ingestions. Toxicity of both alcohols is related to the production of toxic metabolites by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase, resulting in anion gap metabolic acidosis as well as specific organ injuries (Figure 1). Calcium oxalate, derived from EG successive oxidations, may precipitate in tissues,6 mainly in the renal tubules resulting in acute renal failure. Formic acid, derived from methanol oxidation, is responsible for retinal as well as optic nerve damage resulting in poorly reversible visual impairments.7 Recommended management8–10 includes:

supportive care

sodium bicarbonate to correct metabolic acidosis, to increase renal elimination of glycolate and formate, and to inhibit precipitation of calcium oxalate crystals

antidotes, such as a competitive ADH substrate (ethanol) or inhibitor (fomepizole) to block ADH metabolism of the toxic alcohol

dialysis to remove the alcohol and its toxic metabolites, to correct acidosis, and, in the case of methanol poisonings, to shorten the course of hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of methanol and ethylene glycol toxicity. Symptoms are related to the toxic metabolites resulting from successive oxidations by alcohol (ADH) and aldehyde (AldDH) dehydrogenases. The primary site of metabolism is the liver although some methanol metabolism may occur within the retina.

The objectives of this review are to examine the current recommendations regarding fomepizole in the management of toxic alcohol poisonings.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of EG and methanol poisoning

EG is generally responsible for accidental poisonings in young children, generally due to automotive antifreeze misuse due to its bright color and sweet taste. Methanol is a component readily available in many household products such as windshield-washers, paint removers, carburetor cleaners, de-icing and embalming fluids. It is responsible for self-harm and non-intentional intoxications including in chronic alcoholics, as well as in outbreaks due to the marketing of illegal smuggled spirits.2–4,7 Immediately following ingestion, patients generally remain asymptomatic. Some degree of inebriation or mental status alteration may be observed in the first hours following massive ingestions. The major delayed (about 6 to 12 hours or more) effect, related to metabolic acidosis, is a hyperventilation known as Kussmal breathing. Anion gap results from the accumulation of glycolate in EG poisoning or formate in methanol poisoning. Oxalate crystalluria, renal failure, and clinical hypocalcemia are characteristic of EG poisoning. Methanol ingestion results in visual impairment, progressive blindness, and neurological abnormalities (eg, putaminal necrosis), plus several more diffuse symptoms such as dyspnea, chest pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms including vomiting and pain.2,3,8,10 Either alcohol may cause life-threatening arrhythmias, coma, seizures, shock, multiorgan failure, and death.11–13 Methanol-related ocular and neurological injuries are generally irreversible.7

Suspicion of EG or methanol poisoning is based on a history of exposure, physical examination, and blood chemistry tests including arterial blood gases. Evidenced anion gap metabolic acidosis (anion gap = (Na+ + K+) − (HCO3− + Cl−), N < 17 mmol/L), where accumulation of lactate can be expected in the most severe cases due to inhibition of the oxidative metabolism in the mitochondria, reflects the accumulation of either glycolate (EG poisoning) or formate (methanol poisoning). The lactate level can easily be subtracted in a 1:1 manner from the anion gap. Measurement of EG and methanol concentrations in plasma (usually using gas chromatography) is important to confirm the diagnosis. However, these specific assays are not rapidly available in the majority of institutions. Thus, the osmol gap is used routinely as a screening test for the presence of exogenous osmotically active substances such as toxic alcohols, particularly when the ability to measure plasma concentrations of the substances is not available. The osmolal gap is the difference between the measured osmolality and the calculated osmolarity, usually within a range of 5.2 ± 7 mOsm/kg H2O. Osmolality should be measured by freezing point depression. The calculated osmolarity is obtained as follows: serum osmolality (mOsm/l) = 2xNa+ + blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL)/2.8 + glucose (mg/dL)/18. The contribution to the osmolal gap of methanol (1 g/l corresponds to 34 mOsmol/kg H2O), EG (1 g/l corresponds to 17 mOsmol/kg H2O), and ethanol (1 g/l corresponds to 23 mOsmol/kg H2O) are different.

Both osmolal and anion gaps are useful for diagnosis and triage of toxic alcohol-exposed subjects.14 They may be present simultaneously, but as more of the toxic alcohol is metabolized, serum osmolality will fall whereas anion gap will continue to rise.10,14 Confounders are numerous and include low alcohol concentrations (late phase) and concomitant ethanol ingestion. Similarly, presentation with non-anion gap metabolic acidosis should not exclude the diagnosis.15 Lactic acidosis can be present in both poisonings, but is more prominent in the case of very elevated serum glycolate concentrations and may be falsely elevated and confounded with EG if measured using a lactate oxidase-based method.16 Finally, formate can be used as a cheap, simple, and fast diagnostic tool of methanol intoxication, with a high sensitivity and specificity.17

In patients with severe EG intoxication, coma, seizures, severe acidosis (serum HCO3− ≥ 5 mmol/L or pH < 7.00), and hyperkalemia carry a dismal prognosis.11 Poor prognosis in methanol poisonings is associated with coma, seizures, severe acidosis pH < 7.00 and >24 h-delay from intake.12,13 Methanol-poisoned patients with residual visual sequelae have more prolonged acidosis than those with complete recovery.12 Moreover, there seems to be an inverse relationship between surviving and the ability to hyperventilate on admission: patients with a severe metabolic acidosis with a normal or even a high PaCO2 on admission seem to have a poor prognosis compared to the ones hyperventilating. There was a highly significant difference shown in two recent outbreaks:2,4 PaCO2 appears to be a simple tool to evaluate prognosis on admission. Survivors usually present with lower methanol concentrations,3,12 while blood EG levels for the patients who died and those who survived are not significantly different.11 Interestingly, serum glycolate levels above 8 to 10 mmol/L are more likely to develop acute renal failure or die.18

Management of EG and methanol poisoning

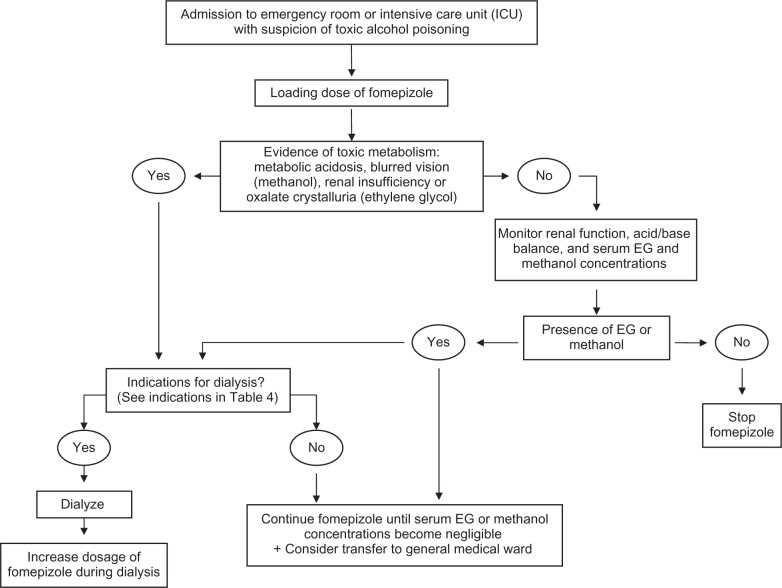

In a case of EG or methanol exposure, the patient should be immediately referred to an emergency department, a poison center, or a consultation with a medical toxicologist (Figure 2).5,19 A facility that can quickly obtain a measurement of the toxic alcohol concentration and has available antidote therapy, is preferred. Gastrointestinal decontamination with gastric lavage (unless within the first hour since ingestion), activated charcoal, or ipecac syrup is not recommended.19 Intentional inhalation of methanol fumes, mainly from carburetor cleaning fluid, may produce elevated plasma concentrations of methanol and formic acid, and should thus be referred, although at low risk of significant metabolic and visual complications.20,21 In contrast, in patients with EG inhalation exposures, will generally not develop systemic toxicity and can be managed out-of-hospital if asymptomatic19 In EG poisoning, referral is not needed if it has been >24 hours since a potentially toxic unintentional exposure, the patient has been asymptomatic, and no alcohol was co-ingested.19 A witnessed taste or lick only by a child or adult who unintentionally drinks and then expectorates the product without swallowing, does not need referral.19

Figure 2.

Algorithm for treatment of EG and methanol poisoned patients.

Poisoned patients should be admitted to a medical ward and in case of life-threatening situation, to an intensive care unit. Sodium bicarbonate is required in case of severe academia (pH < 7.3). Hemodialysis, mechanical ventilation, fluids, and vasopressors may be indicated in severe poisonings. Calcium salts are only recommended in EG poisoning if hypocalcemia significantly contributes to symptoms (muscle spasms or seizures), due to the concern about precipitating calcium oxalate crystals. Other adjunctive treatments have been suggested, however with limited demonstration of benefit: pyridoxine in EG poisoning as cofactor of glycolic acid metabolism to glycine; and folinic acid in methanol poisoning as cofactor of formic acid metabolism to carbon dioxide by tetrahydrofolate synthetase due to the small folate pool in humans.5,8,22

Because of serious morbidity and potential mortality, an antidote to block ADH metabolism of toxic alcohol should be started as soon as possible when indicated, based on history and initial physical findings while awaiting laboratory results.23 The absence of symptoms shortly after ingestion does not exclude a potentially toxic dose and should not be used as a triage criterion.19 The criteria of antidote initiation has been determined by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (Table 1).24,25 The decision to start the treatment cannot be solely based on the result of an assay for toxic alcohols, as this may not be readily available. The current recommendation to treat with a toxic alcohol concentration above 20 mg/dL is protective, although a higher threshold may be as safe.5 Prior to the availability of fomepizole, ethanol was routinely used as an antidote to treat toxic alcohol ingestion. Today, in North-American and Western-European countries, fomepizole is considered as the first-line antidote, based on its efficacy and safety. Thus, in suspected toxic alcohol ingestion or in presence of anion gap metabolic acidosis unexplained by a corresponding increase in serum lactate concentration, we suggest the administration of a loading dose of fomepizole while awaiting definitive diagnosis.

Table 1.

Criteria for initiating fomepizole in case of suspected EG or methanol poisoning

| – Documented recent history of ingestion of a toxic amount of toxic alcohol and osmol gap >10 mosmol/l |

| – Documented plasma concentration ≥20 mg/dL (3.2 mmol/L for ethylene glycol and 6.2 mmol/L for methanol) |

| – Suspected ingestion with at least 3 (for ethylene glycol poisoning) or 2 (for methanol poisoning) of the following criteria: |

| Arterial pH < 7.3 |

| Serum bicarbonate concentration <20 mmol/L |

| Osmolal gap >10 mOsm.l |

| Oxalate crystalluriaa |

Notes:

Consider this criteria only for ethylene glycol exposure.

Fomepizole pharmacological properties

Fomepizole (4-methylpyrazole) is a potent competitive inhibitor of ADH (>8000 times higher affinity than that of ethanol) with limited toxicity. Fomepizole interacts with ADH zinc element and coenzyme nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide, preventing its binding to the toxic alcohol.

Biochemical properties of human liver ADH as well as its role in EG and methanol metabolism have been assessed since 1964. Whilst searching in 1969 for potent ADH inhibitors, Li, Theorell and Yonetani showed that fomepizole inhibited ADH activity in human hepatocytes. In parallel, fomepizole antidotal activity was assessed in animal models by McMartin (for methanol)31 and Clay and Murphy (for EG). In the 1970s, Blomstrand and Theorell first administered fomepizole to human volunteers, aiming to study its consequences on ethanol biological effects. In the 1980s, Jacobsen assessed the safety of repeated doses in humans. Accordingly, fomepizole has been successfully used in France in EG26,27 and methanol28 poisonings, since 1981. In the US, fomepziole was granted FDA marketing approval in 1997 for EG poisoning treatment, while an extension of indication was obtained in 2000 for methanol poisonings. Finally, in 1999 and 2001, two U.S. multi-center prospective clinical trials were published, definitively assessing fomepizole’s efficacy in the treatment of both toxic alcohols.29,30

Fomepizole pharmacokinetics have been extensively studied. Fomepizole’s volume of distribution is in the range of 0.6–1.0 l/kg and its plasma protein binding is low. Fomepizole has four metabolites: 4-hydroxymethylpyrazole, the only active metabolite, with approximately 1/3 the potency of the parent compound, 4-carboxypyrazole, and glucuronide conjugates of both metabolites.23,31 Fomepizole is virtually entirely eliminated by saturable hepatic metabolism, with a Km of 0.94 μmol/L, a concentration always markedly exceeded during therapeutic use.23,32,33 The currently accepted minimum effective plasma concentration, derived from studies assessing the complete inhibition of formate accumulation in methanol-poisoned monkeys, is 10 μmol/L (= 0.8 μg/mL).31 In the US studies, complete inhibition was reached in each case, with plasma fomepizole concentrations exceeding 10 μmol/L.31,32 Accordingly, although mostly administered by intravenous route, fomepizole is rapidly and almost completely absorbed orally, resulting in nearly identical blood levels as well as identical time above the target concentration of 10 μmol/L with both routes.32,33 Elimination is characterized by dose-dependent, non-linear zero order kinetics, with a rate of 4–15 μmol/L/h.32,34 All four metabolites are present in the urine, with a predominance of 4-carboxypyrazole.

Based on animal studies, even a single dose may induce cytochrome P450 2E1, resulting in an increase in its own elimination rate within a short time frame (after 48 hours of administration).32 However, the exact mechanism of such an autoinduction remains unclear, although a mechanism based on post-translational modifications (protein stabilization or translation) appears more possible than a transcriptional increase of the enzyme synthesis.23

When associated with ethanol, therapeutic doses of fomepizole were shown in human volunteers, to result in a 40%-reduction in the rate of elimination of ethanol. Pretreatment with fomepizole significantly prolonged ethanol neurobehavioral toxicity in a mice model.35 Conversely, ethanol was demonstrated to inhibit fomepizole metabolism, consequently increasing its blood concentration.34 Thus, previous ethanol intake or administration before fomepizole therapy does not decrease its efficacy as an antidote. However, the clinical relevance of the fomepizole effect on ethanol elimination remains to be determined.

Clinical use of fomepizole in EG and methanol poisonings

Although no controlled studies exist, available data clearly demonstrates that fomepizole is safe and effective for the treatment of EG and methanol poisoning. Prognosis of these poisonings is therefore dependent on the delay from ingestion to fomepizole initiation and on the amount of parent compound at the time of treatment.5 In all the studies, no lethality or significant morbidity has occurred with either alcohol when patients were treated before significant toxic metabolism occurred; all patients recovered from their poisonings. Rapid resolution of acidosis accompanied clinical improvement, with no new symptoms of poisoning after the initiation of therapy. Treatment with fomepizole efficiently prevented glycolate and formate formation. Both EG and methanol toxicokinetics were altered, with a first order elimination and prolonged half-life, respectively around 20 and 52 h, for EG and methanol.28–30,36–39

No significant interaction of fomepizole with any pharmaceutical has been reported. Contraindication of fomepizole administration is allergy to pyrazole derivates such as phenylbutazone although never associated with any of pyrazole’s serious toxicities. Case studies and clinical trials indicate that fomepizole is well tolerated, although headache (12%), nausea (11%), dizziness (7%), and injection site irritation have been reported.29,30 Other adverse reactions included rash, lymphangitis, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, tachycardia, hypotension, vertigo, slurred speech, inebriation, fever, mild transient eosinophilia and slight increases in hepatic transaminases. None of these reactions required discontinuation of therapy. However, in one reported case, fomepizole precipitated bradycardia and/or hypotension during hemodialysis.40 During pregnancy, fomepizole is still not recommended in the absence of safety data. Although not formally studied in children, several pediatric cases suggest its clinical efficacy without unusual side effects other than nystagmus.41–48

Current dosing recommendations include a 15 mg/kg loading dose followed by four 10 mg/kg doses every 12 hours during the first 48 hours and then 15 mg/kg doses every 12 hours for the remainder of the therapy.5 An increase to 15 mg/kg over 48 h was recommended by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology, to account for a presumed enhance of fomepizole clearance due to CYP2E1 autoinduction.24,25 However, in the presence of EG or methanol, decreased fomepizole elimination was also reported, contributing to prolonging its therapeutic effects.23,34 Standard-dose regimen resulted in fomepizole concentrations considerably exceeding the minimum therapeutic concentration (>10 μmol/L).5 Therefore, a different regimen (15 mg/kg loading dose followed by 10 mg/kg each 12 hours with tapering doses until alcohol concentration is ≤30 mg/dL), is currently used in France (Table 2).9 Interestingly, other authors have suggested a higher initial 20 mg/kg dose to easily overcome the possibility of metabolism induction and to negate any need for dose adjustment during treatment without dialysis therapy.23 Finally, therapy should be discontinued when plasma concentrations are ≤30 mg/dL (4.8 mmol/L for EG and 9.4 mmol/L for methanol).

Table 2.

European dosage regimen of fomepizole in ethylene glycol poisoning: fomepizole is administered every 12 hours, by oral or intravenous route, according to plasma ethylene glycol concentrations

| Ethylene glycol plasma concentration

|

Fomepizole (mg/kg)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/dL | mmol/L | Loading dose | 2nd dose T + 12 h | 3rd dose T + 24 h | 4th dose T + 36 h | 5th dose T + 48 h | 6th dose T + 60 h |

| 600 | 96 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7.5 | 5 |

| 300 | 48 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7.5 | |

| 150 | 24 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 7.5 | ||

| 75 | 12 | 15 | 10 | 7.5 | |||

| 35 | 5.6 | 15 | 7.5 | ||||

| 20–30 | 1.6–5.5 | 15 | |||||

No dose adjustment is required in case of renal or hepatic diseases. In case of combined hemodialysis, two different protocols were proposed to compensate for fomepizole extraction. The U.S. manufacturer recommends a reduction in the dosing interval from 12 h to 4 h, while European authors have proposed a continuous IV infusion of 1–1.5 mg/kg/h for the entire duration of the hemodialysis session following the initial loading dose.49,50 Since hemodialysis duration depends on initial EG or methanol concentration, a continuous infusion protocol appears simpler and sufficient to maintain fomepizole above the minimally effective concentration.

The place of hemodialysis when fomepizole is used

Hemodialysis is considered as an integral part of the treatment of toxic alcohol poisonings to expedite removal of the alcohol and its metabolites, thus reducing the duration of antidotal treatment. EG and methanol are efficiently cleared by dialysis (Table 3).9 Hemodialysis effectively clears glycolate, with an elimination half-life of 155 ± 474 min, compared to the spontaneous elimination half-life of 625 ± 474 min.51 In contrast, although clearing formate, hemodialysis effectiveness in significantly increasing formate elimination (half-lives: 150 ± 37 min versus 205 ± 90 min;37 1.7 h versus 2.6 h;38 1.80 ± 0.78 h versus 6.04 ± 3.26 h)39 is debated. Conflicting results are related to the small cohorts of patients while an unexpectedly great inter-individual variation of formate half-life exists.22,52

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of ethylene glycol and methanol and their alteration in relation to fomepizole and hemodialysis

| Ethylene glycol | Methanol | |

|---|---|---|

| Lethal dose | 1.4–1.6 mL/kg | 1.2 mL/kg (risk of blindness: 10–15 mL) |

| Elimination | Zero or 1st order | Zero order |

| Total body clearance | 70 mL/min | 11 mL/min |

| Renal clearance* | 17–39 mL/min | 1 mL/min |

| Half-life + fomepizole | ~20 h | ~52 h |

| Half-life under dialysis | 150–210 min | 197–219 min |

| Dialysis clearance** | 192–210 mL/min | 95–176 mL/min |

| Metabolite clearance*** | 254 mL/min | 223 mL/min |

Notes:

Dependent on renal function.

Dependent on blood flow during hemodyalisis.

Glycolate for ethylene glycol and formate for methanol.

The current criteria for hemodialysis in EG poisonings include severe metabolic acidosis, renal failure, electrolyte imbalances unresponsive to conventional therapy, and deterio-rating vital signs despite intensive supportive care (Table 4).9,24 EG-poisoned patients treated with fomepizole prior to the onset of significant acidosis did not require hemodialysis.27 An EG concentration above 50 mg/dL (8.1 mmol/L) should no longer be considered as an independent criterion for hemodialysis in patients treated with fomepizole.53 Initial serum glycolic acid concentration appears to be a good indicator for hemodialysis, however, this measurement is not readily available in most hospitals. Initial glycolic acid >10 mmol/L predicts acute renal failure, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 94% and an efficiency of 98%.18 Dialysis is unnecessary, regardless of EG level, if glycolic acid is ≤8 mmol/L in patients receiving antidote. Anion gap >20 mmol/L or pH < 7.30, but not EG concentration, are predictive of acute renal failure.18 In one patient with a very elevated EG concentration and despite adequate fomepizole administration, hyperosmolality and its subsequent electrolyte imbalances required hemodialysis.54

Table 4.

Recommendations for hemodialysis in ethylene glycol and methanol poisoning

| – Arterial pH < 7.10 |

| – Drop in arterial pH > 0.05 resulting in a pH outside the normal range despite bicarbonate infusion |

| – Inability to maintain arterial pH > 7.3 despite bicarbonate therapy |

| – Decrease in bicarbonate concentration >5 mmol/L, despite bicarbonate therapy |

| – Renal failure (serum creatinine concentration >265 μmol/L or rise in the serum creatinine by >90 μmol/L) |

| – Deteriorating vital signs despite intensive supportive care |

| – Visual or neurological impairment in case of methanol poisoning |

| – Initial plasma methanol concentration ≥50 mg/dL (15.6 mmol/L)a |

| – Rate of methanol decline < 10 mg/dL (3.1 mmol/L) per 24 hours (delayed hemodialysis) |

The current criteria for hemodialysis in methanol poisonings include severe metabolic acidosis, renal failure, electrolyte disturbance unresponsive to conventional therapy, visual symptoms, deteriorating vital signs despite intensive care, and plasma methanol concentration ≥50 mg/dL (15.6 mmol/L) (Table 4).25,38 Due to methanol’s long elimination half-life when ADH is inhibited (about 52 h),22,28 antidote administration must be prolonged, whereas normal renal clearance of EG appears sufficient to avoid a prolonged course of fomepizole. Prolonged fomepizole administration may obviate the need to dialyze poisonings involving high methanol concentrations (≥50 mg/dL and far above, up to 146 mg/dL in one successfully treated case), without severe acidosis or visual impairment.5,25,38 Delayed hemodialysis or even no hemodialysis may be an option in selected cases.22 Visual impairment is traditionally considered an absolute indication for dialysis, supported by possible recovery of visual impairment despite initial alteration in electrophysiological examinations.55,56 Fomepizole appears safe in patients exhibiting retinal toxicity, despite its potential to inhibit retinol dehydrogenase (ADH isoenzyme, essential to vision).55

The traditional end-point of dialysis is a plasma concentration of the toxic alcohol <20 mg/dL, with resolution of acid-base disturbances and the osmolar gap.24,25 A simple method to estimate the required dialysis time has been validated.57 The required time (RDT) to reach a 5 mmol/L toxicant concentration is estimated as follows: RDT (h) = [−V.Ln(5/A)]/0.06k, with V (l) representing the Watson estimation of total body water, A (mmol/L) the initial toxicant concentration, and k (mL/min) 80% of the manufacturer-specified dialyser urea clearance. When alcohol concentration is not known, an 8 h-duration hemodialysis should generally be sufficient. However, after an initial hemodialysis in methanol poisonings, persistence of ocular abnormalities should not be considered as an indication for continued dialysis. Methanol-induced optic nerve injury usually persists once the acute phase of toxicity has resolved.5,7

Why use fomepizole instead of ethanol?

While a comparison of fomepizole with ethanol (with or without hemodialysis) would be of interest, such a study has never been done. Interestingly, using a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model, fomepizole was shown, if administered early enough, to be more effective than ethanol or hemodialysis in preventing EG metabolism to toxic metabolites.58

There are several reasons for prefering fomepizole: it is a more potent ADH inhibitor with a wider therapeutic index, a longer duration of action, easier dosing, and more predictable kinetics. Its administration regimen is easy, including a fixed loading dose independent of baseline alcohol concentration followed by intermittent bolus doses every 12 hours with no need for continuous infusion. Fomepizole is better tolerated, even during prolonged administration (up to 8 days), than ethanol (adjusted hazard ratio for drug event rates: 0.16 [95%-confidence interval 0.06, 0.40]).59 No significant central nervous system, hypoglycemia, liver toxicity or pancreatitis occurs with fomepizole, in contrast with ethanol therapy.60 There is no need for blood concentration monitoring, as therapeutic concentrations are reliably achieved with the proposed dosing regimens. In contrast, ethanol therapy requires blood concentration monitoring (antidote-targeting concentrations ≥100 mg/dL) and intravenous glucose administration, in an intensive care unit, especially for pediatric poisonings.46 Studies have shown that up to 85% of patients had ethanol concentrations above the therapeutic limit.22 While dialysis is often mandatory, adjustment of maintenance ethanol infusion rate represents an additional difficulty.

Moreover, based on a small series, we showed that asymptomatic adult patients referred to the emergency department for evaluation after ingesting a potentially toxic quantity of toxic alcohol received oral fomepizole safely and efficiently.61 Therefore we had sufficient time to obtain the plasma concentration of the alcohol, as delayed treatment may be deleterious. Given its safety, especially in patients who may subsequently be found not to be poisoned, fomepizole permits a margin of diagnostic error. Similarly, based on prehospital diagnosis using a portable blood gas analyzer, early fomepizole administration may be safely considered in the out-of-hospital setting.62 Finally, in selected EG as well as methanol patients, fomepizole may obviate the need for hemodialysis.5,9,22,27,28

There are frequent references to the minimal cost of parenteral ethanol in comparison with the relatively high cost of fomepizole ($800 per 1.5 g).5 Hospitals seeing only occasionally EG or methanol poisonings and hospitals with easily available hemodialysis,63 may prefer ethanol antidote therapy. Fomepizole shelf life (about 3 years), replacement at no charge after expiration in some cases, and limiting inappropriate use, determine the ongoing budget more than acquisition costs.9,64 To date, the costs of ethanol for intravenous use and generic fomepizole tend to be similar.5 Moreover, any comparison between both antidotes should not ignore the critical issue of laboratory costs for monitoring serum ethanol and blood glucose, the increased nursing care required for inebriated patients, and the requirement for intensive care. The risks, costs and inconvenience of prolonged hospitalization if fomepizole alone is used, must be weighed against those of hemodialysis, if ethanol is preferred. Hemodialysis represents an invasive technique with risks of adverse effects, and is not universally available, especially in cases of epidemic poisonings.3,4 Thus, we believe that ethanol combined with hemodialysis should be administered only when fomepizole is unavailable or contraindicated. However in the US, despite all these advantages, treatments with fomepizole still suffer from significant delays and is used less frequently than recommended by poison center staff.65

Conclusion

Fomepizole is an effective and safe first-line antidote in preventing or diminishing EG and methanol toxicity. Its availability in developing countries and its optimal use in developed countries still represent important concerns. While antidotal therapy without hemodialysis is efficacious in selected cases of uncomplicated poisonings, further experience is still needed to clearly define the indications for associated hemodialysis.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Heard SE. American Association of Poison Control Centers. 2007 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46(10):927–1057. doi: 10.1080/15563650802559632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hovda KE, Hunderi OH, Tafjord AB, Dunlop O, Rudberg N, Jacobsen D. Methanol outbreak in Norway 2002–2004: epidemiology, clinical features and prognostic signs. J Intern Med. 2005;258(2):181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brahmi N, Blel Y, Abidi N, et al. Methanol poisoning in Tunisia: report of 16 cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(6):717–720. doi: 10.1080/15563650701502600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paasma R, Hovda KE, Tikkerberi A, Jacobsen D. Methanol mass poisoning in Estonia: outbreak in 154 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(2):152–157. doi: 10.1080/15563650600956329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brent J. Fomepizole for ethylene glycol and methanol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2216–2223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0806112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Froberg K, Dorion RP, McMartin KE. The role of calcium oxalate crystal deposition in cerebral vessels during ethylene glycol poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44(3):315–318. doi: 10.1080/15563650600588460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paasma R, Hovda KE, Jacobsen D. Methanol poisoning and long term sequelae – a six years follow-up after a large methanol outbreak. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen D, McMartin KE. Antidotes for methanol and ethylene glycol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(2):127–143. doi: 10.3109/15563659709001182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mégarbane B, Borron SW, Baud FJ. Current recommendations for treatment of severe toxic alcohol poisonings. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(2):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraut JA, Kurtz I. Toxic alcohol ingestions: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(1):208–225. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03220807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hylander B, Kjellstrand CM. Prognostic factors and treatment of severe ethylene glycol intoxication. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(6):546–552. doi: 10.1007/BF01708094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu JJ, Daya MR, Carrasquillo O, Kales SN. Prognostic factors in patients with methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(3):175–181. doi: 10.3109/15563659809028937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Pajoumand A, Dadgar SM, Shadnia SH. Prognostic factors in methanol poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26(7):583–586. doi: 10.1177/0960327106080077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovda KE, Hunderi OH, Rudberg N, Froyshov S, Jacobsen D. Anion and osmolal gaps in the diagnosis of methanol poisoning: clinical study in 28 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(9):1842–1846. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soghoian S, Sinert R, Wiener SW, Hoffman RS. Ethylene glycol toxicity presenting with non-anion gap metabolic acidosis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;104(1):22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan TJ, Clark C, Clague A. Artifactual elevation of measured plasma L-lactate concentration in the presence of glycolate. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(10):2177–2179. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199910000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hvoda KE, Urdal P, Jacobsen D. Increased serum formate in the diagnosis of methanol poisoning. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29(6):586–588. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter WH, Rutter PW, Bush BA, Papas AA, Dunnington JE. Ethylene glycol toxicity: the role of serum glycolic acid in hemodialysis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2001;39(6):607–615. doi: 10.1081/clt-100108493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caravati EM, Erdman AR, Christianson G, et al. Ethylene glycol exposure: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2005;43(5):327–345. doi: 10.1080/07313820500184971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace EA, Green AS. Methanol toxicity secondary to inhalant abuse in adult men. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47(3):239–242. doi: 10.1080/15563650802498781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bebarta VS, Heard K, Dart RC. Inhalational abuse of methanol products: elevated methanol and formate levels without vision loss. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(6):725–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hovda KE, Jacobsen D. Expert opinion: fomepizole may ameliorate the need for hemodialysis in methanol poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(7):539–546. doi: 10.1177/0960327108095992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bestic M, Blackford M, Reed M. Fomepizole: a critical assessment of current dosing recommendations. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49(2):130–137. doi: 10.1177/0091270008327142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barceloux DG, Krenzelok EO, Olson K, Watson W. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1999;37(5):537–560. doi: 10.1081/clt-100102445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barceloux DG, Bong GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology ad Hoc Committee on the Treatment Guidelines for Methanol Poisoning. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40(4):415–446. doi: 10.1081/clt-120006745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baud FJ, Galliot M, Astier A, et al. Treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning with intravenous 4-methylpyrazole. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:97–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807143190206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borron SW, Mégarbane B, Baud FJ. Fomepizole in treatment of uncomplicated ethylene glycol poisoning. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):831. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mégarbane B, Borron SW, Trout H, et al. Treatment of acute methanol poisoning with fomepizole. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1370–1378. doi: 10.1007/s001340101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brent J, McMartin K, Phillips S, et al. Fomepizole for the treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning. Methylpyrazole for Toxic Alcohols Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(11):832–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brent J, McMartin K, Philipps S, Aaron C, Kulig K, Methylpyrazole for Toxic Alcohols Study Group Fomepizole for the treatment of methanol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(6):424–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMartin KE, Hedström KG, Tolf BR, Ostling-Wintzell H, Blomstrand R. Studies on the metabolic interactions between 4-methylpyrazole and methanol using the monkey as an animal model. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1980;199(2):606–614. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(80)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobsen D, Barron SK, Sebastian CS, Blomstrand R, McMartin KE. Non-linear kinetics of 4-methylpyrazole in healthy human subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;37(6):599–604. doi: 10.1007/BF00562552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marraffa J, Forrest A, Grant W, Stork C, McMartin K, Howland MA. Oral administration of fomepizole produces similar blood levels as identical intravenous dose. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46(3):181–186. doi: 10.1080/15563650701373796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobsen D, Sebastian CS, Dies DF, et al. Kinetic interactions between 4-methylpyrazole and ethanol in healthy humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(5):804–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Páez AM, Shannon M, Maher T, Quang L. Effects of 4-methylpyrazole on ethanol neurobehavioral toxicity in CD-1 mice. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(8):820–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivilotti ML, Burns MJ, McMartin KE, Brent J. Toxicokinetics of ethylene glycol during fomepizole therapy : implications for management. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;36(2):114–125. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.107002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerns W, 2nd, Tomaszewski C, McMartin K, Ford M, Brent J, META Study Group Methylpyrazole for Toxic Alcohols: Formate kinetics in methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40(2):137–143. doi: 10.1081/clt-120004401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hovda KE, Andersson KS, Urdal P, Jacobsen D. Methanol and formate kinetics during treatment with fomepizole. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2005;43(4):221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hantson P, Haufroid V, Wallemacq P. Formate kinetics in methanol poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24(2):55–59. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht503oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepik KJ, Brubacher JR, DeWitt CR, et al. Bradycardia and hypotension associated with fomepizole infusion during hemodialysis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46(6):570–573. doi: 10.1080/15563650701725128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harry P, Jobard E, Briand M, Caubet A, Turcant A. Ethylene glycol poisoning in a child treated with 4-methylpyrazole. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3):E31. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baum CR, Langman CB, Oker EE, Goldstein CA, Aviles SR, Makar JK. Fomepizole treatment of ethylene glycol poisoning in an infant. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1489–1491. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benitez JG, Swanson-Biearman B, Krenzelok EP. Nystagmus secondary to fomepizole administration in a pediatric patient. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38(7):795–798. doi: 10.1081/clt-100102394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyer EW, Mejia M, Woolf A, Shannon M. Severe ethylene glycol ingestion treated without hemodialysis. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):172–173. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown MJ, Shannon MW, Woolf A, Boyer EW. Childhood methanol ingestion treated with fomepizole and hemodialysis. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):77–79. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy M, Bailey B, Chalut D, Senécal PE, Gandreault P. What are the adverse effects of ethanol used as an antidote in the treatment of suspected methanol poisoning in children. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41(1):155–161. doi: 10.1081/clt-120019131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caravati EM, Heileson HL, Jones M. Treatment of severe pediatric ethylene glycol intoxication without hemodialysis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(3):255–259. doi: 10.1081/clt-120037424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Detaille T, Wallemacq P, Clément de Cléty S, et al. Fomepizole alone for severe infant ethylene glycol poisoning. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(5):490–491. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000128600.17670.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faissel H, Houze P, Baud FJ, Scherrmann JM. 4-methylpyrazole monitoring during hemodialysis of ethylene glycol intoxicated patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;49(3):211–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00192381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jobard E, Harry P, Turcant A, Roy PM, Allain P. 4-methylpyrazole and hemodialysis in ethylene glycol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34(4):379–381. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moreau CL, Kerns W, II, Tomaszewski CA, et al. Glycolate kinetics and hemodialysis in ethylene glycol poisoining. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(7):659–666. doi: 10.3109/15563659809162613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hovda KE, Mundal H, Urdal P, McMartin K, Jacobsen D. Extremely slow formate elimination in severe methanol poisoning: a fatal case report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(5):516–521. doi: 10.1080/15563650701354150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson WA. Ethylene glycol toxicity: closing in on rational, evidence-based treatment. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(2):139–141. doi: 10.1067/mem.2000.108655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pizon AF, Brooks DE. Hyperosmolality: another indication for hemodialysis following acute ethylene glycol poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44(2):181–183. doi: 10.1080/15563650500514582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sivilotti ML, Burns MJ, Aaron CK, McMartin KE, Brent J. Reversal of severe methanol-induced visual impairment: no evidence of retinal toxicity due to fomepizole. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2001;39(6):627–631. doi: 10.1081/clt-100108496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Essama Mbia JJ, Guerit JM, Haufroid V, Hantson P. Fomepizole therapy for reversal of visual impairment after methanol poisoning: a case documented by visual evoked potentials investigation. Am J Ophtalmol. 2002;134(6):914–916. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirsch DJ, Jindal KK, Wong P, Fraser AD. A simple method to estimate the required dialysis time for cases of alcohol poisoning. Kidney Int. 2001;60(5):2021–2024. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corley RA, McMartin KE. Incorporation of therapeutic interventions in physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of human clinical case reports of accidental or intentional overdosing with ethylene glycol. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85(1):491–501. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lepik KJ, Levy AR, Sobolev BG, et al. Adverse drug events associated with the antidotes for methanol and ethylene glycol poisoning: a comparison of ethanol and fomepizole. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hantson P, Mahieu P. Pancreatic injury following acute methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2000;38(3):297–303. doi: 10.1081/clt-100100935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mégarbane B, Houzé P, Baud FJ. Oral fomepizole administration to treat ethylene glycol and methanol poisonings: advantages and limitations. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46(10):1097. doi: 10.1080/15563650802310911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amathieu R, Merouani M, Borron SW, Lapostolle F, Smail N, Adnet F. Prehospital diagnosis of massive ethylene glycol poisoning and use of an early antidote. Resuscitation. 2006;70(2):285–286. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anseeuw K, Sabbe MB, Legrand A. Methanol poisoning: the duality between ‘fast and cheap’ and ‘slow and expensive’. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):107–109. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3282f3c13b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mycyk MB, DesLauriers C, Metz J, Wills B, Mazor SS. Compliance with poison center fomepizole recommendations is suboptimal in cases of toxic alcohol poisoning. Am J Ther. 2006;13(6):485–489. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000208878.53856.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sivilotti ML. Ethanol: tastes great! Fomepizole: less filling! Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(4):451–453. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]