Abstract

Background

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed and potentially irreversible motor complication arising in patients chronically exposed to centrally-active dopamine D2 receptor antagonists, including antipsychotic drugs and metoclopramide. The classical dopamine D2 receptor supersensitivity hypothesis in TD, which stemmed from rodent studies, lacks strong support in humans.

Methods

To investigate the neurochemical basis of TD, we chronically exposed adult capuchin monkeys to haloperidol (median 18.5 months, N=11) or clozapine (median 6 months, N=6). Six unmedicated animals were used as controls. Five haloperidol-treated animals developed mild TD movements, and no TD was observed in the clozapine group. Using receptor autoradiography, we measured dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptor levels. We also examined the D3 receptor/preprotachykinin mRNA co-expression, and quantified preproenkephalin mRNA levels, in striatal sections.

Results

Unlike clozapine, haloperidol strongly induced dopamine D3 receptor binding sites in the anterior caudate-putamen, particularly in TD animals, and binding levels positively correlated with TD intensity. Interestingly, D3 receptor upregulation is observed in striatonigral output pathway. In contrast, D2 receptor binding was comparable to controls, and dopamine D1 receptor binding was reduced in the anterior (haloperidol and clozapine) and posterior (clozapine) putamen. Enkephalin mRNA widely increased in all animals, but to a greater extent in TD-free animals.

Conclusions

These results suggest for the first time that upregulated striatal D3 receptors correlate with TD in non-human primates, adding new insights to the dopamine receptor supersensitivity hypothesis. The D3 receptor could provide a novel target for drug intervention in human TD.

Keywords: dopamine receptors, antipsychotic drugs, basal ganglia, tardive dyskinesia

Introduction

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an unsolved and potentially disabling condition encompassing all delayed, persistent, and often irreversible abnormal involuntary movements arising in a fraction of subjects during long-term exposure to centrally-acting dopamine receptor-blocking agents such as antipsychotic drugs (APDs) and metoclopramide.1 It remains prevalent worldwide even in children,2 although a prospective study yielded an adjusted TD incidence rate-ratio one-third less for adults treated with newer-generation (“atypical”) APDs alone compared to first-generation (conventional) agents.3 Treatment options are non specific and produce mixed results.

The pathogenesis of TD has proved complex. Very few, well controlled, clinicopathological studies have been published, and none of the proposed hypotheses, namely dopamine D2 receptor supersensitivity, striatal neurodegeneration, maladaptive synaptic plasticity, and enhanced serotonin 5-HT2 receptor signaling, have been satisfactorily confirmed in monkeys and humans.4–5 The classic hypothesis of the existence of dopamine D2 receptor supersensitivity in TD stemmed from rodent studies in which short-term exposure to conventional APDs was almost constantly associated with increased numbers of D2 receptors6–8 and increased mRNA levels.8–9 Single administration of haloperidol also enhanced receptor responsiveness to the dopamine agonist apomorphine.10 Yet those data failed to explain TD occurrence in a fraction of APD-exposed human subjects, and the delay necessary for induction. Protracted (6–8 months) APD treatments in rats have produced increased striatal D2 binding,11 mRNA levels,12 and affinity to ligands,13 but unchanged D2 binding has also been reported.14 Further, in some chronic rat experiments, striatal D2 receptor density15 and mRNA levels12 were found similar between animals with or without oral TD-like movements. Positron emission tomography (PET) studies did not show a difference in D2 receptor density between APD-treated patients with or without TD,16–17 and no post-mortem evidence for striatal dopamine D2 receptor upregulation was found in TD patients.18–20

In the past decade, the dopamine D3 receptor has drawn attention as a possible mediator of hyperkinetic movement disorders, including levodopa-induced dyskinesia.21–22 Several groups proposed that there might be a genetic predisposition to TD in some ethnic groups carrying the gly9 polymorphism in the dopamine D3 receptor gene,23–24 which reportedly enhances the affinity to dopamine compared to the ser9 receptor.25 This polymorphism is also present in capuchin monkeys used experimentally.26 While traditionally not seen as a prime target of APDs in vivo in humans,27 the D3 receptor displays strong affinity in vitro for these drugs, which could then contribute to the response profile. One PET study in baboons using the D3-preferring ligand (+)-PHNO also suggested that both haloperidol and clozapine acutely bind to D3 receptors in vivo.28 Behavioural studies conducted in monkeys using partially selective D3 receptor agents have suggested an involvement of this receptor subtype in TD.29

Given the variability in rodent data, we chronically exposed Cebus apella monkeys to typical or atypical APDs to revisit the dopamine receptor supersensitivity hypothesis, in an attempt to correlate TD induction and severity with dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptor levels measured by autoradiography, a technique allowing detailed anatomic dissection of the basal ganglia and use of a highly D3-selective ligand unavailable for in vivo imaging. We also examined markers of direct and indirect striatal output neurons,30–31 as part of an over-arching goal to find novel therapeutic targets and drugs that could be readily translated from primates to humans with TD.

Methods and Materials

Animals and treatments

Handling of primates proceeded in accordance to the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approval of the local Animal Care Committee. Twenty-three adult ovariectomized female capuchin (Cebus apella) monkeys were used, in order to match the endocrine status and purported high TD risk of postmenopausal women. A detailed description of treatments and behavioral measures can be found elsewhere.32 Briefly, 11 animals were injected on a weekly basis with a depot preparation of haloperidol decanoate (0.1–0.9 mg/kg i.m.) (estimated dose between 28–252 mg/month in humans). In the absence of direct pharmacokinetic studies comparing drug handling in capuchins and humans, doses were first selected according to those used by research groups in the field, and individually adjusted to avoid acute dystonic reactions and excessive motor slowing. In the TD group, the mean (±SD) latency of onset of TD was 19 (±12) months (range 7–35 months). In the TD-free animals, mean duration of drug exposure was 19 (±4.5) months (range 16–27 months). Six control animals received the atypical APD clozapine at clinically relevant doses, individually titrated to avoid adverse effects (overt sedation or motor slowing), given twice daily at 5–8 mg/kg/dose (estimated dose between 700–1120 mg/day in humans) in a fruit 5 days a week for 6 months (cumulative doses ranging from 600–960 mg/kg). This duration of exposure to clozapine was deemed sufficient to achieve chronic drug impregnation, as this study was not an attempt to compare the dyskinesigenic potential between clozapine and haloperidol. During the last weeks of exposure, the depot haloperidol group was switched to an oral preparation (0.125–0.3 mg/kg twice daily in a fruit) (estimated dose between 16–42 mg/day in humans) in order for all drug-exposed animals to receive their last medication dose 3 h prior to sacrifice. Six animals served as untreated controls.

TD measure

The orofacial (forehead, lips, tongue, jaw), neck, trunk, and limb movements were scored along a primate equivalent of the Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale, with each body segment scored between 0–4 points from absent to severe TD, for a maximum score of 40 points. A similar scale (ratings between 0–3 points) is used in non-human primate studies of levodopa-induced dyskinesia.33 During drug exposure, the presence of TD was deemed unequivocal when persistent over time (>3 months) and a minimum of two separate body segments scored at least 1 point, or a minimum of one body part scored 2 points or more, at least part of the time. Motor rating took place over 15 min each hour for 4 consecutive hours. The cumulative score obtained for all 4 observations is used, and a total score of 0 required for TD-free animals.

Tissue preparation

Following sacrifice and body perfusion with physiologic saline, the brains were removed, immersed in 2-methylbutane at −50°C for 15 sec, and then kept frozen at −80°C. Hemisected brains were cut into coronal sections of 12 μm on a cryostat (−20°C). The slices were thaw-mounted onto SuperFrostPlus (Fisher Scientific Ltd, Nepean, ON, Canada) 75 × 50 mm slides and stored at −80°C until use.

Receptor autoradiography

[3H]SCH23390 binding autoradiography to dopamine D1 receptor was adapted from previous reports with minor modifications.34 Slides were incubated with 2 nM [3H]SCH23390 (specific activity 91 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada) and non-specific binding was evaluated in the presence of 1 μM SCH23390, as customarily done due to the lack of other D1-selective ligands. [125I]iodosulpride binding was used to label dopamine D2 receptors. [125I]iodosulpride autoradiography protocol was adapted with minor modifications.35 Brain sections were incubated with 0.2 nM [125I]iodosulpride (specific activity 2200 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada). Non-specific binding was evaluated in the presence of 2 μM raclopride. [125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding to dopamine D3 receptor autoradiography was adapted with minor modifications.36 Brain sections were incubated with 0.2 nM [125I]7-OH-PIPAT (specific activity 2200 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada). Non-specific binding was evaluated in the presence of 1 μM dopamine. Additional information on dopamine receptor autoradiography experimental conditions can be found in supplementary material on the website.

In situ hybridization

Preproenkephalin (PPE) probe preparation

A cDNA oligonucleotide probe complementary to bases 388–435 (GenBank accession no. NM_006211) of the human PPE sequence of the cloned PPE-A cDNA was labeled at the 3′-end by terminal transferase (New England Biolabs, Whitby, ON, Canada) with a [35S]-dATP (1250 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada) using a 3′-terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase enzyme kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d’Urfé, QC, Canada). The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 30 min and labeled oligonucleotide was purified on a QIAquick Nucleotide removal Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada).

PPE mRNA hybridization

In situ hybridization of the PPE probe was performed as previously described.37 In brief, sections were fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. After pre-hybridization steps, [35S]-labeled oligonucleotide probe was added in the hybridization buffer to reach a concentration of 1 × 107 cpm/slide. The hybridization buffer was composed of 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 0.25 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 0.5 mg/ml denaturated salmon sperm DNA, and 4X SSC and incubated at 37°C for 15 h in a humid chamber. After several washings, the slide-mounted tissue sections were exposed to BioMax MR films (Kodak, New Haven, CT) for 15 days at room temperature. The films were developed and autoradiograms analyzed by densitometry.

Quantification of autoradiograms

Quantification of the autoradiograms was performed using computerized analysis (ImageJ 1.45s software, Wayne Rasband, NIH). Digital brain images were taken using a Grayscale Digital Camera (Model CFW-1612M, Scion Corporation, Maryland, USA). Optical gray densities were transformed into nCi/g of tissue equivalent using standard curves generated with 14C- or 3H-microscales (ARC 146A-14C or ARC 123A-3H standards, American Radiolabelled Chemicals Inc., St-Louis). The brain areas under examination included anterior and posterior parts of the caudate nucleus (CD) and putamen corresponding to Bregma 2.70 to 0.45 (anterior caudate-putamen) and Bregma −6.30 to −8.10 (posterior caudate-putamen), respectively.38 Anterior and posterior putamen regions have been subdivided into medial (PM) and lateral (PL) portions. Quantifications were also performed in nucleus accumbens (Acc), globus pallidus internal segment (GPi) and external segment (GPe), and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and pars reticulata (SNr) levels. Average levels of labeling for each area were calculated from three to four adjacent brain sections of the same animal. Background intensities were taken in white matter tracts for each section and were subtracted from every measurement.

Double in situ hybridization procedure

The double in situ hybridization procedure was performed as described previously,39 with [35S]UTP-labeled D3 receptors and non-radioactive dioxygenin (Dig)-labeled preprotachykinin (PPT), which produces substance P.40 The substance P neuropeptide is expressed in the same cell population as dynorphin and was chosen as a marker of the direct striatal efferent pathway activity because it displays higher basal expression than dynorphin.41 For the dopamine D3 receptor probe, a complementary DNA fragment (from nucleotides 167 to 830) was amplified from striatal monkey total RNA. The fragment was then subcloned into pCRII/TOPO plasmid. The antisense cRNA probe was obtained by plasmid linearization with XhoI and polymerization with the SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of [35S]UTP (1250 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada), The PPT probe (200 bp fragment from nucleotides 78 to 277) was prepared and Dig-labeled as previously described.39 The Dig cRNA probe (PPT, 0.75 ng/μl) was added in the hybridization mix with the D3 receptor radioactive-labeled probe (4–5 × 106 cpm/μl). After overnight incubation and washing procedures, slides were processed for Dig revelation. When an adequate staining was obtained, reaction was stopped and slides were dipped in LM-1 photographic emulsion (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) previously melted at 42°C for 3 h. Two months later, emulsion was developed in D-19 developer (3.5 min) and fixed (5 min) in Rapid Fixer solution (Kodak, New Haven, CT). Slides were mounted using a water-soluble mounting medium. Single- and double-labeled cells were visualized and manually counted with an Axio Imager A.1 photo microscope (Carl Zeiss Canada Ltd, Montreal, QC, Canada) at 400X magnification. Neuron counting was performed in 5–10 different fields within the anterior dorsal putamen. Double-labeled cells were identified by the apposition of more than 10 silver grains with the colored product of the Dig reaction. Neuron counting was estimated on 4 different sections obtained from a total of 4 animals per group investigated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All data were expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. Statistical comparison of mRNA levels in controls, haloperidol- and clozapine-treated groups was performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We first performed a test of homogeneity using Bartlett’s test, followed by a logarithmic transformation (when Bartlett’s test was significant) and finally applied a one-way ANOVA on transformed data. When the ANOVA revealed significant differences, a Tukey’s test was performed as post hoc analysis. Comparison between dyskinetic and non dyskinetic haloperidol-treated animals was performed using an unpaired t-test with a two-tailed p value. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Five out of 11 capuchins treated with haloperidol developed lasting spontaneous TD. TD scores (±SD) have been reported elsewhere (mean of 16.5 (±8.5) points for the group).32 The resulting abnormal purposeless movements were similar to those found in humans and typically mild and stereotyped in nature, involving the oral and axial/limb musculature, at times admixed with dystonic features. The selected doses of clozapine were well tolerated and caused neither acute dystonic reactions nor TD within 6 months.

Effect of antipsychotic drugs on dopamine receptor binding

[3H]SCH23390 specific binding distribution was homogenous throughout anterior and posterior caudate-putaman subterritories (Fig. S1). Chronic haloperidol and clozapine treatments reduced [3H]SCH23390 specific binding to dopamine D1 receptors in the anterior medial putamen region, whereas clozapine, but not haloperidol, also reduced binding levels in posterior caudate and posterior lateral putamen (Fig. S1).

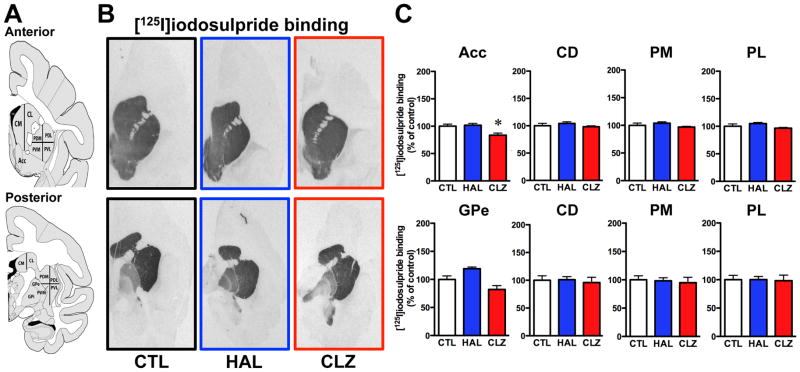

[125I]iodosulpride specific binding levels were high in nucleus accumbens, and all anterior and posterior caudate-putamen areas (Fig. 1A, B). [125I]Iodosulpride binding displayed a posterior putamen medial-to-lateral gradient of expression (Fig. 1B). Lower [125I]iodosulpride specific binding was found in the GPe, whereas almost undetectable labeling was observed in the GPi in untreated animals (Fig. 1B). Chronic APD exposure was associated with caudate-putamen dopamine D2 receptor binding site levels largely comparable to unmedicated controls (Fig. 1C), regardless of the motor status of the animals. Dopamine D2 receptor binding capacities were not altered by APD in the GPe (Fig. 1C), but a strong haloperidol-induced iodosulpride binding capacity upregulation was observed in the GPi (CTL = 100 ± 12%; HAL = 226 ± 9% [p<0.01 vs CTL group]; CLZ = 97 ± 39%).

Figure 1.

[125I]iodosulpride binding at D2 receptors. A) The left panels illustrate schematic representations of monkey brain coronal sections taken at anterior (top) and posterior (bottom) levels of the basal ganglia subdivision areas used for quantification. B) Representative autoradiograms in anterior (top panels) and posterior (bottom panels) of [125I]iodosulpride binding in unmedicated control (CTL), haloperidol (HAL)- and clozapine (CLZ)-exposed groups. C) Histograms showing binding results expressed in percentages relative to CTL group values. (*p<0.05 vs CTL group). Abbreviations: Acc, nucleus accumbens; CD, caudate nucleus; PM, medial putamen; PL, lateral putamen; GPe, external globus pallidus.

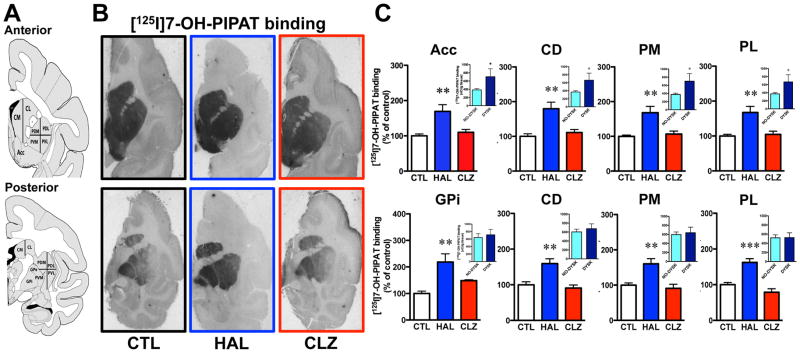

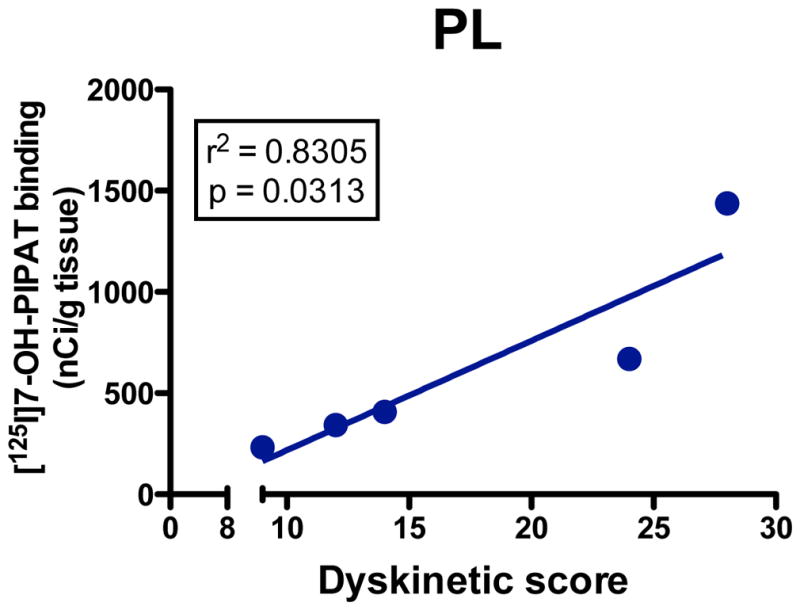

[125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding displayed an anterior-to-posterior gradient of labeling in caudate-putamen subterritories in control animals (Fig. 2A, B). Within posterior putamen, [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding capacity was found higher medially than laterally (Fig. 2B). This gradient is reverse to that observed with [125I]iodosulpride. Thus, receptor distribution is consistent with the notion that [125I]iodosulpride binds to both D2 and D3 receptors, with a D2:D3 ratio more prominent in the anterior striatum of untreated animals in our experimental conditions. High levels of [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding were observed in the GPi in untreated animals (Fig. 2B). [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding distribution is also consistent with previous reports on the distribution of dopamine D3 receptors in both monkeys and humans.42 Unlike clozapine, haloperidol strongly upregulated [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding to dopamine D3 receptors in all regions examined relative to controls (Fig. 2C). We also compared [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding in haloperidol-treated animals with or without TD. Monkeys with TD had significantly higher D3 receptor binding capacities compared to TD-free animals in the anterior striatal areas examined, but not posteriorly (Fig. 2C, insets). Interestingly, D3 receptor levels also correlated with TD intensity in the lateral putamen area (Fig. 3) but not with total duration of drug exposure, given the goodness of fit obtained (calculated r2=0.064) and lack of a significantly different slope from zero (p=0.51) among all haloperidol-exposed monkeys. [125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding levels were also upregulated in both GP segments, GPi (Fig. 2C) and GPe (CTL = 100 ± 9%; HAL = 219 ± 31% [p<0.01 vs CTL group]; CLZ = 148 ± 3%). In SNr, both haloperidol and clozapine significantly upregulated [125I]7-OH-PIPAT specific binding (Fig. S2D–F available on website).

Figure 2.

[125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding at D3 receptors. A) Coronal sections taken as in figure 1. B) Representative autoradiograms from controls (CTL), haloperidol-treated (HAL) and clozapine-treated (CLZ) animals. C) Histograms showing binding results expressed in percentages relative to CTL group values (**p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs CTL groups). Insets: comparison of [125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding in haloperidol-treated monkeys without (No-dysk) and with (Dysk) tardive dyskinesia (*p<0.05 vs No-dysk respective group). Abbreviations: Acc, nucleus accumbens; CD, caudate nucleus; PM, medial putamen; PL, lateral putamen; GPi, internal globus pallidus.

Figure 3.

Linear regression curve showing correlation between [125I]7-OH-PIPAT binding (nCi/mg tissue) in lateral putamen (PL) and tardive dyskinesia scores in 5 monkeys chronically exposed to haloperidol. Regression analysis indicates that the correlation explains about 80% of the variance in the group.

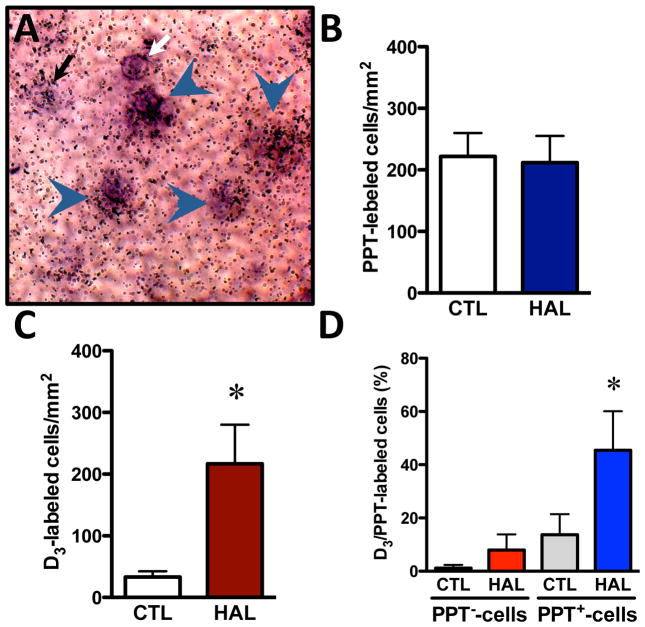

Localization of dopamine D3 receptors in striatal cell subpopulations

We measured localization of the dopamine D3 receptor mRNA in PPT-negative and PPT-positive cells of the striatum using a double in situ hybridization procedure in which the D3 receptor 35S-labeled probe can be visualized by silver grain accumulations, whereas the PPT Dig-labeled probe appears as cellular brown deposits (Fig. 4A). Quantification of single Dig-labeled cells (PPT-positive cells) in controls and haloperidol-treated animals indicated similar PPT mRNA levels in both experimental conditions (Fig. 4B). In the anterior lateral putamen area, haloperidol significantly increased the number of cells expressing D3 receptor mRNA (Fig. 4C), and selectively increased (3.3-fold) the fraction of D3 receptor labeling in PPT-positive cells (Fig. 4D). Haloperidol treatment did not modulate the D3 receptor labeling in PPT-negative cells (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Double in situ hybridization procedure with [35S]UTP-labeled D3 receptors and non-radioactive dioxygenin (Dig)-labeled preprotachykinin (PPT), which produces substance P. Neuron counting was measured in 5–10 different fields within the anterior dorsal putamen, on 4 different sections obtained from a total of 3 animals per group. A) Examples of D3-labeled cell (black arrow), PPT-labeled cell (white arrow), and double-labeled D3/PPT cells (arrowheads) identified by the apposition of more than 10 silver grains with the colored product of the Dig reaction (photograph magnification 400X). B) Histograms showing number of single-labeled cells/mm2 for the PPT probe in controls (CTL) and haloperidol-treated (HAL) animals. C) Histograms showing number of single-labeled cells/mm2 for the D3 receptor probe in controls (CTL) and haloperidol-treated (HAL) animals (*p<0.05 vs CTL group). D) Histograms showing the percentage of D3 receptor-labeled cells in PPT−-cells and PPT+-cells in controls (CTL) and haloperidol-treated (HAL) animals (*p<0.05 vs CTL SP+-cells group).

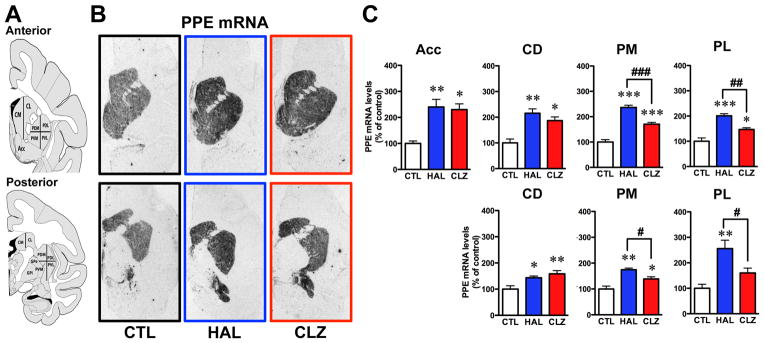

Effect of antipsychotic drugs on enkephalin expression

[35S]-PPE-labeled probe showed strong signal throughout nucleus accumbens and caudate-putamen subterritories (Fig. 5A, B). The PPE mRNA signal, expressed in indirect striatopallidal output neurons, was increased by haloperidol and clozapine in all striatal subregions (Fig. 5C). However, haloperidol-exposed animals displayed significantly higher PPE mRNA levels compared to clozapine-treated monkeys in the putamen (Fig. 5C). An additional analysis of the haloperidol group indicated that TD monkeys expressed lower PPE mRNA levels compared to TD-free animals in the posterior dorsolateral putamen (No-Dysk = 263 ± 35 and Dysk = 159 ± 23 nCi/g tissue, p=0.0352).

Figure 5.

Preproenkephalin (PPE) mRNA hybridization. A) Coronal sections taken as in figure 1. B) Representative autoradiograms obtained from untreated controls (CTL), haloperidol-treated (HAL) and clozapine-treated (CLZ) animals. C) Histograms showing densitometry results expressed in percentages relative to CTL group values (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs CTL respective groups; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 and ###p<0.001 vs HAL group). Abbreviations: Acc, nucleus accumbens; CD, caudate nucleus; PM, medial putamen; PL, lateral putamen.

Discussion

Chronic APD impregnation in capuchins caused distinct changes on dopamine D2-like receptors. In accordance with some rodent data,14 striatal D2-labeled [125I]iodosulpride binding sites were found at comparable levels between unmedicated and chronically medicated capuchins under haloperidol, regardless of TD status. Evidently, these results should not be construed as reflecting lack of regulation of dopamine D2 receptors by APDs, but provide no support for the dopamine D2 receptor supersensitivity hypothesis of TD. However, in stark contrast to previous protocols of APD exposure conducted in rats that yielded no D3 receptor upregulation in the motor striatum, with mRNA levels8–9,43 and binding density8,11 generally found unchanged, we observed for the first time in monkeys that long-term haloperidol exposure causes a robust upregulation in D3 receptors in striatonigral neurons, selectively in the presence of TD. This increase also correlates with TD intensity in the lateral putamen, not with the total duration of haloperidol exposure. Interestingly, chronic clozapine administration spared D3 receptors, but we acknowledge the fact that the duration of exposure (6 months) may be insufficient to be conclusive in that regard. The foregoing results obtained with haloperidol raise an important caveat in the reliance of experimental TD data restricted to rodents, and the possibility of fundamental inter-species differences in terms of D3 receptor biology. Methodological issues alone are unlikely involved, given that D1 receptor binding results following APD exposure appear not so dissimilar between rats and monkeys.

We also found the D3 receptor widely distributed in striatal and extrastriatal regions, in agreement with previous results obtained in monkeys,44 in human post-mortem brain tissues,42 and in PET-based in vivo brain imaging using the D3-preferring ligand (+)-PHNO.45 Strong basal expression of D3 receptor binding sites (labeled with [125I]7-OH-PIPAT) in the GPi is consistent with localization along the direct striatonigral output pathway, given the preferential expression of D3 receptor mRNA in PPT-positive cells. Very low levels of iodosulpride binding were observed in the GPi, as opposed to 7-OH-PIPAT binding, in untreated animals. To our surprise, haloperidol induced strong iodosulpride binding in the GPi, perhaps reflecting D3 rather than D2 receptor labeling. Such explanation would agree with primate PET imaging data suggesting that the (+)-PHNO signal in the GP mainly represents binding at the dopamine D3 receptor subtype.46–47

Importantly, haloperidol upregulated D3 receptors selectively in PPT-positive neurons of origin of the direct striatal efferent pathway. While haloperidol modulates molecular components in cells expressing D2 receptors,48–50 the drug also displays affinity for D3 receptors, which are mainly co-localized with D1 receptors in the striatum.51 It is still unclear how dopamine D3 receptor upregulation might contribute to TD at the cellular or circuit level, but D3 receptors have been associated with behavioral sensitization52–53 and levodopa-induced dyskinesia,21,54 possibly suggesting common mechanisms. Furthermore, overactivation of the dopamine D1-expressing direct striatonigral pathway has been linked with hyperkinetic movements.52,55 Although, studies have generally found no correlation between dopamine D1 receptors labeling or gene expression and oral TD-like movements in rats,11,56–57 our study indicates that clozapine reduced D1 receptor binding sites in the posterior putamen, a finding of unknown significance at present, but of potential interest in view of the antidyskinetic properties of the drug in humans.58–59

Finally, despite the apparent lack of variations in D2 receptor density between our experimental groups, APDs still cause distinct changes along the indirect striatal efferent pathway. For instance, haloperidol, not clozapine, upregulated striatal adenosine A2a receptors in rats.60 Both typical (haloperidol) and atypical (clozapine) APDs enhanced enkephalin mRNA levels in all the striatal regions we examined, but to a larger magnitude in the haloperidol group, as reported previously.30,61–62 Importantly, this elevation was more noticeable in TD-free animals. In the past, striatal enkephalin overexpression resulting from APDs in rats has been interpreted as reflecting increased activity along the indirect striatopallidal pathway contributing to TD.63 Previous observations generated in murine and primate models of TD suggested that the nuclear receptor Nur77 is induced in central dopaminoceptive pathways as part of a neuroadaptive response.32 Indeed, Nur77 knockout mice displayed enhanced vacuous chewing to haloperidol compared to wild-type littermates,64 and TD monkeys had significantly lower Nur77 mRNA levels than TD-free animals.32 While haloperidol-induced Nur77 expression is selectively observed in enkephalin-expressing cells of the striatum,31 haloperidol-induced enkephalin expression is totally blunted in Nur77 knockout mice, suggesting that this neuropeptide is a target of Nur77-dependent transcriptional activity. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the rise in enkephalin mRNA levels along the indirect striatopallidal pathway might be part of the adaptive response mounted against TD, as proposed for experimental levodopa-induced dyskinesia.65

In conclusion, the foregoing results suggest that the dopamine receptor supersensitivity hypothesis of TD should not entirely be dismissed, but that upregulated striatal D3 not D2 receptors are associated with the motor complication in a non-human primate model. The D3 receptor could provide a novel target for drug intervention in human TD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mrs. Marie-T. Parent, as well as the staff of the animal care facilities at Université de Montréal and Institut National de Recherche Scientifique (Armand-Frappier Institute, Laval, Canada), for their assistance and expertise during the animal experiments. This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR, MOP-81321). S.M. holds a doctoral studentship from “Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQ-S)”.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: Dr. Blanchet reports having received lecture fees from Novartis Pharma Canada Inc., and consultation fees from UCB Pharma. Dr. Mahmoudi and Dr. Lévesque declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Roles

S. Mahmoudi: 1) Research project: C; 2) Statistical analysis: B; 3) Manuscript: B.

D. Lévesque: 1) Research project: ABC; 2) Statistical analysis: AB; 3) Manuscript: B.

P. Blanchet: 1) Research project: ABC; 2) Statistical analysis: C; 3) Manuscript: A.

References

- 1.Blanchet PJ. Antipsychotic drug-induced movement disorders. Can J Neurol Sci. 2003;30(Suppl 1):S101–S107. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wonodi I, Reeves G, Carmichael D, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in children treated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1777–1782. doi: 10.1002/mds.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods SW, Morgenstern H, Saksa JR, et al. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with atypical versus conventional antipsychotic medications: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:463–474. doi: 10.4088/JCP.07m03890yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creed-Carson M, Oraha A, Nobrega JN. Effects of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists on acute and chronic dyskinetic effects induced by haloperidol in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2011;219:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waln O, Jankovic J. An update on tardive dyskinesia: From phenomenology to treatment. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2013;3 doi: 10.7916/D88P5Z71. http://tremorjournal.org/article/view/161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klawans HL, Rubovits R. An experimental model of tardive dyskinesia. J Neural Transm. 1972;33:235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF01245320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt DR, Creese I, Snyder SH. Antischizophrenic drugs: chronic treatment elevates dopamine receptor binding in brain. Science. 1977;196:326–328. doi: 10.1126/science.847477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lévesque D, Martres MP, Diaz J, et al. A paradoxical regulation of the dopamine D3 receptor expression suggests the involvement of an anterograde factor from dopamine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1719–1723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Souza U, McGuffin P, Buckland PR. Antipsychotic regulation of dopamine D1, D2 and D3 receptor mRNA. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1689–1696. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martres M-P, Costentin J, Baudry M, Marcais H, Protais P, Schwartz J-C. Long-term changes in the sensitivity of pre- and postsynaptic dopamine receptors in mouse striatum evidenced by behavioural and biochemical studies. Brain Res. 1977;136:319–337. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florijn WJ, Tarazi FI, Creese I. Dopamine receptor subtypes: differential regulation after 8 months treatment with antipsychotic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachus SE, Yang E, Sukontarak McCloskey S, Nealon Minton J. Parallels between behavioral and neurochemical variability in the rat vacuous chewing movement model of tardive dyskinesia. Behav Brain Res. 2012;231:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clow A, Jenner P, Marsden CD. An experimental model of tardive dyskinesias. Life Sci. 1978;23:421–424. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waddington JL, Cross AJ, Gamble SJ, Bourne RC. Spontaneous orofacial dyskinesia and dopaminergic function in rats after 6 months of neuroleptic treatment. Science. 1983;220:530–532. doi: 10.1126/science.6132447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirakawa O, Tamminga CA. Basal ganglia GABAA and dopamine D1 binding site correlates of haloperidol-induced oral dyskinesias in rat. Exp Neurol. 1994;127:62–69. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blin J, Baron JC, Cambon H, et al. Striatal dopamine D2 receptors in tardive dyskinesia: PET study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:1248–1252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.11.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson U, Eckernäs SA, Hartvig P, Ulin J, Langström B, Häggström JE. Striatal binding of 11C-NMSP studied with positron emission tomography in patients with persistent tardive dyskinesia: no evidence for altered dopamine D2 receptor binding. J Neural Transm [GenSect] 1990;79:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01245132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riederer P, Jellinger K, Gabriel E. 3H-spiperone binding to post-mortem putamen in paranoid and non-paranoid schizophrenics. In: Pichot P, editor. Psychiatry: The State of the Art. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornhuber J, Riederer P, Reynolds GP, Beckmann H, Jellinger K, Gabriel E. 3H-Spiperone binding sites in post-mortem brains from schizophrenic patients: relationship to neuroleptic drug treatment, abnormal movements, and positive symptoms. J Neural Transm. 1989;75:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01250639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds GP, Brown JE, McCall JC, Mackay AVP. Dopamine receptor abnormalities in the striatum and pallidum in tardive dyskinesia: a post mortem study. J Neural Transm [GenSect] 1992;87:225–230. doi: 10.1007/BF01245368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bezard E, Ferry S, Mach U, et al. Attenuation of levodopa-induced dyskinesia by normalizing dopamine D3 receptor function. Nat Med. 2003;9:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nm875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visanji NP, Fox SH, Johnston T, Reyes G, Millan MJ, Brotchie JM. Dopamine D3 receptor stimulation underlies the development of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steen VM, Lovlie R, MacEwan T, McCreadie RG. Dopamine D3-receptor gene variant and susceptibility to tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenic patients. Molec Psychiatry. 1997;2:139–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakker PR, van Harten PN, van Os J. Antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia and the Ser9Gly polymorphism in the DRD3 gene: a meta analysis. Schizophr Res. 2006;83:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundstrom K, Turpin MP. Proposed schizophrenia-related gene polymorphism: expression of the Ser9Gly mutant human dopamine D3 receptor with the Semliki Forest virus system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225:1068–1072. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werge T, Elbaek Z, Andersen MB, Lundbaek JA, Rasmussen HB. Cebus apella, a nonhuman primate highly susceptible to neuroleptic side effects, carries the GLY9 dopamine receptor D3 associated with tardive dyskinesia in humans. The Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3:97–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick PN, Wilson VS, Wilson AA, Remington GJ. Acutely administered antipsychotic drugs are highly selective for dopamine D2 over D3 receptors. Pharmacological Res. 2013;70:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girgis RR, Xu X, Miyake N, et al. In vivo binding of antipsychotics to D3 and D2 receptors: A PET study in baboons with [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:887–895. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malik P, Andersen MB, Peacock L. The effects of dopamine D3 agonists and antagonists in a nonhuman primate model of tardive dyskinesia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:805–810. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong JS, Yang H-YT, Gillin JC, Costa E. Effects of long-term administration of antipsychotic drugs on enkephalinergic neurons. In: Cattabeni F, Racagni G, Spano PF, Costa E, editors. Long-Term Effects of Neuroleptics. Advances in Biochemical Psychopharmacology. Vol. 24. New York: Raven Press; 1980. pp. 223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ethier I, Beaudry G, St-Hilaire M, Milbrandt J, Rouillard C, Lévesque D. The transcription factor NGFI-B (Nur77) and retinoids play a critical role in acute neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal effect and striatal neuropeptide gene expression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:335–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmoudi S, Blanchet PJ, Lévesque D. Haloperidol-induced striatal Nur77 expression in a non-human primate model of tardive dyskinesia. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:2192–2198. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez-Mancilla B, Bedard PJ. Effect of D1 and D2 agonists and antagonists on dyskinesia produced by L-DOPA in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1991;259:409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savasta M, Dubois A, Scatton B. Autoradiographic localization of D1 dopamine receptors in the rat brain with [3H]SCH 23390. Brain Res. 1986;375:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martres M-P, Bouthenet M-L, Sokoloff P, Schwartz J-C. Widespread distribution of brain dopamine receptors evidenced with [125I]iodosulpride, a highly selective ligand. Science. 1985;228:752–755. doi: 10.1126/science.3838821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanwood GD, Artymyshyn RP, Kung M-P, Kung HF, Lucki I, McGonigle P. Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of rat brain dopamine D3 binding with [125I]7-OH-PIPAT: Evidence for the presence of D3 receptors on dopaminergic and nondopaminergic cell bodies and terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:1223–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morissette M, Goulet M, Soghomonian JJ, et al. Preproenkephalin mRNA expression in the caudate-putamen of MPTP monkeys after chronic treatment with the D2 agonist U91356A in continuous or intermittent mode of administration: comparison with L-DOPA therapy. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;49:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxinos G. The rhesus monkey brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Boston: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmoudi S, Samadi P, Gilbert F, et al. Nur77 mRNA levels and L-Dopa-induced dyskinesias in MPTP monkeys treated with docosahexaenoic acid. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause JE, Chirgwin JM, Carter MS, Xu ZS, Hershey AD. Three rat preprotachykinin mRNAs encode the neuropeptides substance P and neurokinin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:881–885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerfen CR, Young WS., 3rd Distribution of striatonigral and striatopallidal peptidergic neurons in both patch and matrix compartments: an in situ hybridization histochemistry and fluorescent retrograde tracing study. Brain Res. 1988;460:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J, Xu J, Cairns NJ, Perlmutter JS, Mach RH. Dopamine D1, D2, D3 receptors, vesicular monoamine transporter type-2 (VMAT2) and dopamine transporter (DAT) densities in aged human brain. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang W, Hahn KH, Bishop JF, Gao DQ, Jose PA, Mouradian MM. Up-regulation of D3 dopamine receptor mRNA by neuroleptics. Synapse. 1996;23:232–235. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199607)23:3<232::AID-SYN13>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morissette M, Goulet M, Grondin R, et al. Associative and limbic regions of monkey striatum express high levels of dopamine D3 receptors: effects of MPTP and dopamine agonist replacement therapies. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2565–2573. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Searle G, Beaver JD, Comley RA, et al. Imaging dopamine D3 receptors in the human brain with positron emission tomography, [11C]PHNO, and a selective D3 receptor antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graff-Guerrero A, Mamo D, Shammi CM, et al. The effect of antipsychotics on the high-affinity state of D2 and D3 receptors. A positron emission tomography study with [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:606–615. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girgis RR, Xu X, Miyake N, et al. In vivo binding of antipsychotics to D3 and D2 receptors: a PET study in baboons with [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:887–895. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller JC. Induction of c-fos mRNA expression in rat striatum by neuroleptic drugs. J Neurochem. 1990;54:1453–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beaudry G, Langlois MC, Weppe I, Rouillard C, Lévesque D. Contrasting patterns and cellular specificity of transcriptional regulation of the nuclear receptor nerve growth factor-inducible B by haloperidol and clozapine in the rat forebrain. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1694–1702. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, et al. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z. Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J Neuroscience. 1996;16:6579–6591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bordet R, Ridray S, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Involvement of the direct striatonigral pathway in levodopa-induced sensitization in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2117–2123. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillin O, Diaz J, Carroll P, Griffon N, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. BDNF controls dopamine D3 receptor expression and triggers behavioural sensitization. Nature. 2001;411:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35075076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu A, Togasaki DM, Bezard E, et al. Effect of the D3 dopamine receptor partial agonist BP897 [N-[4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazinyl)butyl]-2-naphthamide] on L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-induced dyskinesias and parkinsonism in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:770–777. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guigoni C, Aubert I, Li Q, et al. Pathogenesis of levodopa-induced dyskinesia: focus on D1 and D3 dopamine receptors. Parkinsonism Rel Disord. 2005;11:S25–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sasaki T, Kennedy JL, Nobrega JN. Regional brain changes in [3H]SCH 23390 binding to dopamine D1 receptors after long-term haloperidol treatment: lack of correspondence with the development of vacuous chewing movements. Behav Brain Res. 1998;90:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petersen R, Finsen B, Andreassen OA, Zimmer J, Jorgensen HA. No changes in dopamine D1 receptor mRNA expression neurons in the dorsal striatum of rats with oral movements induced by long-term haloperidol administration. Brain Res. 2000;859:394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Littrell K, Magill AM. The effect of clozapine on preexisting tardive dyskinesia. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1993;31:14–18. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19930901-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spivak B, Mester R, Abesgaus J, et al. Clozapine treatment for neuroleptic-induced tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism, and chronic akathisia in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:318–322. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parsons B, Togasaki DM, Kassir S, Przedborski S. Neuroleptics up-regulate adenosine A2a receptors in rat striatum: Implications for the mechanism and the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2057–2064. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Normand E, Popovici T, Fellmann D, Bloch B. Anatomical study of enkephalin gene expression in the rat forebrain following haloperidol treatment. Neurosci Lett. 1987;83:232–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andreassen OA, Waage J, Finsen B, Jørgensen HA. Memantine attenuates the increase in striatal preproenkephalin mRNA expression and development of haloperidol-induced persistent oral dyskinesias in rats. Brain Res. 2003;994:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Egan MF, Hurd Y, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, Wyatt RJ, Kleinman JE. Alterations in mRNA levels of D2 receptors and neuropeptides in striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons of rats with neuroleptic-induced dyskinesias. Synapse. 1994;18:178–189. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ethier I, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Rouillard C, Lévesque D. Docosahexaenoic acid reduces haloperidol-induced dyskinesias in mice: involvement of Nur77 and retinoid receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Samadi P, Bédard PJ, Rouillard C. Opioids and motor complications in Parkinson’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.