Abstract

This study highlights how Familias Unidas, a Hispanic-specific, evidence-based, family centered preventive intervention, progressed from intervention development (type 1 translation; T1) through rigorous evaluation (T2) and examines the role of intervention fidelity—adherence and competence—in a T3 trial. Effects of participant, provider, and organizational variables on direct (observational) and indirect (self-reported) fidelity were examined as were effects of fidelity. Two structural equation models were estimated using data from 367 Hispanic parent-adolescent dyads randomized to Familias Unidas. Facilitator perceptions of parental involvement in schools, school performance grade, and school socioeconomic status predicted indirect adherence ratings, which were positively related to adolescent substance use. Facilitator openness to evidence-based practices was associated with indirect competence ratings, school performance grade and size were associated with direct competence ratings, and direct competence ratings were negatively associated with substance use. Findings highlight unique contributions of direct and indirect fidelity ratings in the implementation of Familias Unidas.

Keywords: Translation, Fidelity, Preventive intervention, Hispanic, Adolescent, Substance use

Family based preventive interventions have been shown to be efficacious and effective in preventing and reducing adolescent problem behaviors, including substance use [1]. For evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to have a positive impact at the population level, however, they must be translated into real-world settings. Translation, or the process through which EBIs are brought to scale, has been associated with numerous challenges, many of which are related to ensuring an intervention is delivered as intended, or with fidelity to its core components [2]. As interventions move along the research to practice continuum from efficacy and effectiveness to implementation trials, drift from the original protocol can often occur, making the need to monitor intervention fidelity increasingly important [3]. Despite the need to better understand intervention fidelity for the continued process of translation, research on what factors impact fidelity and the extent to which fidelity impacts the effectiveness of family based preventive interventions is not completely understood. This study thus moves the field of translation forward by examining “real world” factors that affect fidelity, and in turn, how fidelity is related to the effectiveness of Familias Unidas, a family based preventive intervention for Hispanics.

Familias Unidas is a culture-specific, parent-centered intervention, shown to be both efficacious and effective in preventing or reducing a number of adverse health behaviors (e.g., substance use, sexual risk behaviors) in Hispanic adolescents [4–6]. It has been cited by the Institute of Medicine as an efficacious intervention ready to move through more advanced stages in the translational research process [7]. This process, from basic biopsychosocial research to translation into global communities, has been described as occurring across several stages [8] (Table 1). As a program of research, Familias Unidas has moved from initial intervention development (“type 1 (T1) translation”) through rigorous testing with well-defined populations (“T2 translation”) and most recently, to a trial examining its effectiveness (“T3 translation”) [5]. Familias Unidas is continuing to move across the stages of translation (“T4–T5 translation”) and is currently being adapted for both online and international use in South America.

Table 1.

Translational research stages

| Type | Type 0 translation (T0) | Type 1 translation (T1) | Type 2 translation (T2) |

| Definition | The fundamental process of translating findings and discoveries from social, behavioral and biomedical sciences into research applied to prevention intervention. | Moving from bench to bedside. Translation of applied theory to methods and program development. | Moving from bedside to practice and involves translation of program development to implementation. |

| Type | Type 3 translation (T3) | Type 4 translation (T4) | Type 5 translation (T5) |

| Definition | Determining whether efficacy and effectiveness trial outcomes can be replicated under real-world settings. | Wide-scale implementation, adoption and institutionalization of new guidelines, practices, and policies. | Translation to global communities. Involves fundamental, universal change in attitudes, policies, and social systems. |

Because a more detailed summary of the Familias Unidas program of research from T1–T3 has been previously published [4], the translational process is briefly described below. During T1, community stakeholders identified conduct problems and substance use as key concerns among local parents. Given risk and protective factors associated with adolescent risky behaviors are present at multiple levels of the social environment, the ecodevelopmental framework [9] was used to guide intervention development. This framework organizes risk and protective factors from the macrosystem (i.e., broad societal factors, such as Hispanic cultural values) to the microsystem (i.e., contexts in which youth participate directly, such as family, peers, and school). Focus groups with Hispanic parents additionally highlighted the role of acculturation as contributing to youth problem behaviors. As such, problem-posing and participatory learning exercises were built into each session to address a number of relevant cultural issues raised by participants, such as those related to having to raise children in a foreign country (e.g., immigration stress, acculturation, lack of social support). This process, whereby participants are encouraged to raise personally relevant cultural issues, has facilitated the translation of the intervention across diverse contexts and Hispanic populations, including those living outside the USA. During T2, Familias Unidas was rigorously tested across three randomized controlled trials and found to be efficacious in preventing and reducing substance use and sexual risk-taking in universal, selected, and indicated samples. The present study is characteristic of T3 in that parameters associated with the implementation of the Familias Unidas effectiveness trial, conducted in a real-world practice setting by school counselors, are examined to inform the continued process of “scaling up.”

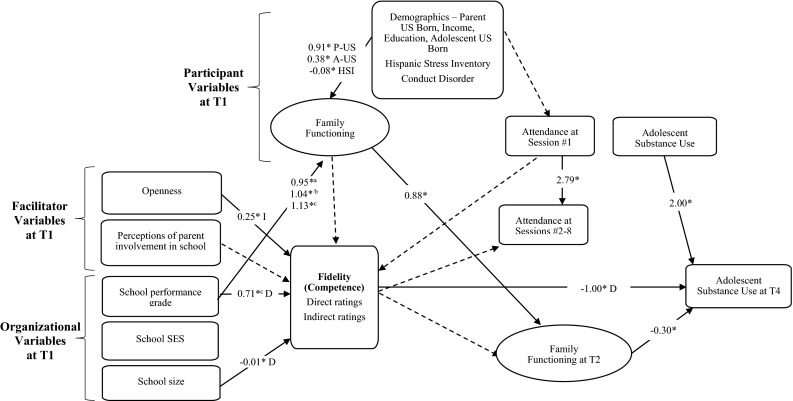

The models that provided the conceptual basis for this study (Figs. 1 and 2) suggest (a) a range of participant, provider, and organizational variables at baseline impact intervention fidelity, and (b) intervention fidelity impacts participant attendance, family functioning, and adolescent substance use, measured up to two and a half years post baseline.

Fig. 1.

Model for adherence. The reported values are unstandardized path coefficients rounded to two decimal places. Dotted lines represent non-significant hypothesized pathways. Model fit without the pathway from school performance grade to family functioning at T1 was unacceptable (CFI = 0.85). This pathway was thus added in accordance with modification indices to improve overall model fit. A-US adolescent US born, D direct ratings of competence, HSI Hispanic Stress Inventory, I indirect ratings of competence, P-US parent US born, SES socioeconomic status, School performance grade was dummy coded with “D” schools as the reference group aA vs. D schools, bB vs. D schools, cC vs. D schools; *p < 0.05

Fig. 2.

Model for competence. The reported values are unstandardized path coefficients rounded to two decimal places. Dotted lines represent non-significant hypothesized pathways. Model fit without the pathway from school performance grade to family functioning at T1 was unacceptable (CFI = 0.85). This pathway was thus added in accordance with modification indices to improve overall model fit. A-US adolescent US born, D direct ratings of competence, HSI Hispanic Stress Inventory, I indirect ratings of competence, P-US parent US born, SES socioeconomic status. School performance grade was dummy coded with “D” schools as the reference group aA vs. D schools, bB vs. D schools, cC vs. D schools; *p < 0.05

THE INFLUENCE OF INTERVENTION FIDELITY ON STUDY MEDIATORS AND OUTCOMES

Intervention fidelity represents a critical aspect of implementation that includes both adherence and competence [10, 11]. Adherence reflects the degree to which an intervention is implemented in accordance with the overarching framework, and competence is related to the level of clinical, or facilitator, skill in promoting behavior change. These indicators of fidelity may be assessed using “direct,” observational measures completed by independent raters and/or “indirect,” self-reported measures completed by interventionists [12]. EBIs for reducing child behavior problems and substance abuse have used fidelity rating systems that jointly account for adherence and competence [10, 11, 13]. For both the Parent Management Training Oregon (PMTO) and Family Check-Up programs, higher direct ratings of competent adherence have predicted increases in effective parenting practices [10, 11, 13], a key intervention mediator, as well as improvements in the primary outcome, child problem behavior [14]. A similar multiple observational framework has been shown to predict outcomes in a school-focused prevention program [15]. More commonly, effects of adherence and competence on intervention mediators and outcomes are evaluated separately. Direct ratings of leader competence have predicted greater changes in observed positive parenting following the Incredible Years Intervention, which in turn, resulted in improvements in child behavior [16]. Contrastingly, higher direct ratings of adherence, but not competence, have been associated with greater declines in adolescent substance use and parent-reported externalizing behaviors in individual and family therapy [17]. Given the importance of maintaining fidelity to the content and process of Familias Unidas, this study examines the separate effects of adherence and competence on family functioning (mediator) and adolescent substance use (outcome). Furthermore, although direct assessments of fidelity currently reflect the gold standard, assessing more cost-effective methods for monitoring fidelity are necessary for translation into practice settings [18]. As such, the present study assesses adherence and competence based on direct and indirect methods.

PARTICIPANT, PROVIDER, AND ORGANIZATIONAL PREDICTORS OF INTERVENTION FIDELITY

Given the importance of implementation for study outcomes, a thorough understanding of factors that affect real-world implementation are critical to moving along translational stages. A systems-contextual approach to understanding implementation and dissemination highlights the role of variables at the participant, provider, and organizational levels [19].

Participant variables

At the participant level, some previous parenting interventions have found that higher fidelity scores are associated with lower baseline parenting scores [11], and Cross et al. [15] tested whether child behavior affected fidelity, finding null results. As noted by Forgatch et al. [11], some family characteristics may make it more or less difficult for facilitators to competently adhere to intervention protocols. Because preventive interventions are likely to have greater variability in participants’ need for assistance than are treatment interventions, more distressed, lower functioning families at baseline (e.g., those with greater levels of stress and problem behaviors, lower skills) may require more structure from a given intervention. As such, facilitators may need to maximize their use of clinical skills and adherent delivery of intervention content based on individual participant characteristics. For Hispanic families, unique risk factors associated with immigration (e.g., adapting to a new culture, language barriers) may compromise family functioning, an important buffer against negative adolescent behavioral outcomes [20].

Characteristics of the family may also impact intervention attendance, which has been positively associated with ratings of fidelity [21]. In previous Familias Unidas efficacy trials, family characteristics (e.g., stress, income, and adolescent behavior problems) were significantly associated with initial engagement to the intervention [22]. Initial engagement and within-group cohesion at the first group session were subsequently related to retention to the intervention [22].

Provider variables

Characteristics of those delivering interventions, including positive attitudes towards EBIs, have also been associated with high-quality implementation [23]. Similar to participants making behavioral changes within preventive interventions, community providers adopting EBIs may differ in their readiness to engage in new practices [24]. While community mental health providers have indicated concerns regarding the relevance of highly controlled (efficacy) studies, they have expressed greater openness to effectiveness research due to its increased external validity [25]. Overall, those more open towards EBIs are more likely to report using them [26].

In the context of the school setting, provider perceptions of school culture, including levels of parental involvement in school, may also be related to how well an EBI is implemented [27]. For example, teacher perceptions of parental involvement in school have been associated with student achievement [28]. Because school counselors were delivering the present intervention, their perceptions of parental involvement were assessed as a predictor of their own practices for delivering the intervention.

Organizational variables

Unique school contextual variables may also impact implementation quality [29]. School size and climate are characteristics linked to fidelity. Providers working in larger schools may have a more difficult time implementing an intervention with fidelity due to competing demands [30, 31]. Because Miami Dade County public schools is the fourth largest school district in the nation and serves a high proportion of low-income ethnic minority families, school counselors may have increased demands placed on their time, which affect their ability to deliver EBIs.

THIS STUDY

This study informs the continued process of translating Familias Unidas by examining how participant, facilitator, and organizational variables impact intervention fidelity (adherence, competence), and in turn, how fidelity impacts family functioning and adolescent substance use within an effectiveness trial. The following was hypothesized: (a) baseline family functioning will have a negative relationship with direct and indirect fidelity ratings; (b) facilitator variables (e.g., openness to EBIs) will be positively related to direct and indirect fidelity ratings; (c) school socioeconomic status (SES) and size will be negatively related, while school performance grade will be positively related to direct and indirect fidelity ratings; and (d) direct and indirect fidelity ratings will be positively associated with attendance and family functioning and negatively associated with substance use, with direct ratings more strongly related to substance use.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 367 adolescents (52 % males, 13.9 ± 0.66 years old, 54 % US born) and their parents (49 % college/graduate school, 34 % income ≥US$30,000/year) recruited from 18 middle schools and randomly assigned at the family or individual level to the intervention condition of the Familias Unidas effectiveness trial [5]. Families were eligible to participate if they had an adolescent in the 8th grade, there was one Hispanic (self-identified) primary caregiver living in the same household as the adolescent willing to participate, they lived within the catchment area of the participating middle schools, and planned to live in South Florida for the duration of the study.

Procedures

The study was approved by the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board and the Miami-Dade County Public Schools Research Ethics Board. Participants completed assessments at 6, 18, and 30 months post baseline.

Intervention description

A detailed description of Familias Unidas can be found elsewhere [4]. Briefly, Familias Unidas is delivered in 12 weekly sessions comprised of eight parent group sessions (where only parents participate) and four family visits (where both parents and adolescents participate). The intervention aims to involve parents in adolescent peer and school activities, facilitate parent-adolescent cohesion, build supportive relationships among parents, and reduce/prevent problem behavior by improving family functioning. School counselors served as facilitators in this trial (52 % delivered the intervention in their school; 48 % at a different school).

Measures

Participant variables

Demographic data included country of birth for parents and youth, parents’ educational level, and household income. Reliable and valid measures were used to assess parent stress (Hispanic Stress Inventory [32]) and adolescent conduct disorder (Revised Behavior Problem Checklist [33]). Finally, parental self-report of three indicators were used to create a latent construct of family functioning, assessed at baseline and the 6-month follow-up: (1) peer monitoring (Parent Relationship with Peer Group Scale [34]), (2) positive parenting (Parenting Practices Scale [35]), and (3) family communication (Family Relations Scale [36]).

Provider variables

Openness towards adopting EBIs was measured at baseline with the openness subscale of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale [37]. Facilitator perceptions of parental involvement in their schools were assessed at baseline using a 20-item measure [28].

Organizational variables

School SES. School SES was assessed using the percentage of students receiving free or reduced school lunch. School performance grades (ranging from “A” (best performing) to “F” (poorest performing) based on academic performance and learning gains) and size were obtained from a publicly available database (www.oada.dadeschools.net). Performance grades among schools in the present study were: “A” (55.6 %), “B” (16.7 %), “C” (22.2 %), and “D” (5.6 %). The average school size was 1020 students (SD = 293).

Attendance

Attendance at the first group session was coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes based on whether or not the participant parent(s) were present. Attendance at group sessions 2–8 was measured by summing across the total number of those sessions attended. Average attendance across the full intervention, including group sessions and family visits was 6.4 ± 4.2 sessions.

Fidelity

Ratings of adherence and competence were conducted using structured, session-specific forms. These forms were completed by facilitators following each group session as well as by trained, independent raters coding videotaped sessions. Facilitators used a 7-point Likert scale to rate each session, with higher scores indicating greater fidelity. Observers used the same 7-point Likert scale to rate sessions in four 30-min segments during each 2-h group session. Twenty percent of all sessions were also coded by a second rater (Kappa > 0.80). Separate scores for direct and indirect measures of adherence and competence were calculated by averaging across group sessions. Adherence. Adherence was measured using 2–7 session-specific items related to how well the facilitator presented content in accordance with the facilitators’ manual. Sample items from the first group session included, “To what extent did the facilitator: process the homework assignment, inform parents about the importance of effective parent-adolescent communication, and coach parent(s) to use communication skills.” Competence. Facilitator competence was measured by the same four items each session: “To what extent did the facilitator: join all members of the group, establish group member alliances, utilize problem-posing and participatory learning methods, and act as a switchboard and/or speak for long periods of the activities.” Item four (switchboard) was reverse scored.

Adolescent substance use

Substance use at baseline and 30 months was assessed using three Y/N items. A binary variable was created to indicate whether adolescents had smoked tobacco, drank alcohol, or used an illicit drug in the past 90 days.

Analytic plan

To test the hypothesized models, a latent family functioning variable at baseline and 6 months was created using peer monitoring, positive parenting, and family communication. The factor loadings and intercepts of family functioning at baseline and 6-month assessments were freely estimated because a repeated measures analysis on family functioning was not conducted, which requires measurement invariance across time points. Second, the hypothesized models were estimated using SEM. Model fit was ascertained using the chi-square index (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Study hypotheses were tested using Mplus (7.2). The default estimator, the mean and variance adjusted weighted least square estimator was used to estimate parameters and standard errors.

RESULTS

Overall fidelity ratings

The average overall fidelity ratings were 3.61 (SD = 0.56) for direct observations and 5.10 (SD = 0.58) for indirect facilitator ratings. Across group sessions, average overall fidelity ratings ranged from 2.04 to 4.30 (M = 3.67, SD = 0.86) for direct observations and 4.86 to 5.25 (M = 5.06, SD = 0.13) for indirect facilitator ratings. Across interventionists, average overall fidelity ratings ranged from 2.40 to 4.75 (M = 3.70, SD = 0.53) for direct observations and 3.80 to 6.0 (M = 5.00, SD = 0.60) for indirect facilitator ratings.

Measurement model

Family functioning

Results from the CFA suggested that the three indicators of family functioning loaded significantly onto a single construct at baseline and 6-month assessments. Standardized loadings at baseline and 6 months, respectively, were as follows: family communication, λ = .50, .59; peer monitoring, λ = .52, .55; and positive parenting, λ = .42, .39.

Correlations between direct and indirect ratings of adherence and competence

Indirect ratings of adherence were negatively associated with direct ratings of competence (r = −.42, p < .05). Indirect ratings of adherence were positively related to indirect ratings of competence (r = .74, p < .05). No other correlations were significant.

Structural equation model: hypothesized “adherence” model

The model for adherence (Fig. 1) provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (164) = 189.75, p = .08; CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.02). Results for the hypothesized paths of interest are discussed in the following sections.

Predictors of adherence

Participant variables: Family functioning at baseline and attendance at the first group session were not significantly related to direct or indirect ratings of adherence. Provider variables: Facilitator perceptions of parental involvement in school were positively associated with indirect ratings of adherence (b = .008, p < .05, 95 % confidence interval (CI) [.001, .015]). Facilitator openness to EBIs was not significantly associated with direct or indirect ratings of adherence. Organizational variables: School size was positively associated with direct ratings of adherence (b = 0.023, p < .05, 95 % CI [.015, .030]). School SES (b = −0.051, p < .05, 95 % CI [−.096, −.007]) and school performance grade (b = −0.791, p < .05, 95 % CI [−.1.565, −.017]) were negatively associated with indirect ratings of adherence. For school performance grade, facilitators delivering the intervention in “C” schools had lower indirect ratings of competence than did those delivering the intervention in “D” schools.

Attendance

Participant demographic characteristics, Hispanic stress, and conduct disorder were not significantly associated with attendance at group session 1. Attendance at group session 1 was positively associated with attendance at group sessions 2–8 (b = 2.821, p < .05, 95 % CI [2.197, 3.446]). Attendance at group sessions 2–8 was not significantly related to family functioning at 6 months.

Effects of adherence

Attendance: Direct ratings of adherence were positively associated with participant attendance at group sessions 2–8 (b = 1.653, p < .05, 95 % CI [.594, 2.712]). Family functioning: Neither direct nor indirect ratings of adherence were related to family functioning at the 6-month assessment. Substance use: Indirect ratings of adherence were positively associated with adolescent substance use at 30 months (b = 0.531, p < 0.05, CI [.153, .910]). The direct measure of adherence was not related to substance use (b = −0.28, p = .50).

Structural equation model: hypothesized “competence” model

The model for competence (Fig. 2) provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (164) = 199.14, p < .05; CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.02). Results for the paths of interest are discussed in the following sections.

Predictors of competence

Participant variables: Family functioning at baseline and attendance at the first group session were not significantly related to direct or indirect ratings of competence. Provider variables: Facilitator openness to EBIs was positively associated with indirect ratings of competence (b = .249, p < .05, 95 % CI [.182, .316]). Facilitator perceptions of parental involvement in school were not significantly associated with direct or indirect ratings of competence. Organizational variables: School performance grade was positively associated with direct ratings of competence (b = .710, p < .05, 95 % CI [.157, 1.263]), such that facilitators delivering the intervention in “C” schools had higher direct ratings of competence than did those delivering the intervention in “D” schools. School size was negatively associated with direct ratings of competence (b = −0.014, p < .05, 95 % CI [−.026, −.003]). School SES was not significantly associated with direct or indirect ratings of competence.

Attendance

Hispanic stress and conduct disorder were not significantly associated with attendance at group session 1. Attendance at group session 1 was positively associated with attendance at group sessions 2–8 (b = 2.787, p < .05, 95 % CI [2.163, 3.310]). Attendance at group sessions 2–8 was not significantly related to family functioning at 6 months.

Effects of competence

Attendance: Neither direct nor indirect ratings of competence were associated with participant attendance at group sessions 2–8. Family functioning: Neither direct nor indirect ratings of competence were significantly related to family functioning at 6 months. Substance use: Direct ratings of competence were negatively associated with adolescent substance use at 30 months (b = −.999, p < 0.05, 95 % CI [−1.682, −.315]).

DISCUSSION

Following the progression of the Familias Unidas program of research from T1 to T3 translation, this study examined the role of fidelity, including adherence and competence, in the implementation of the Familias Unidas effectiveness trial. Participant, provider, and organizational predictors of intervention fidelity (measured using direct, observational ratings and indirect, self-reported ratings) were examined as was the impact of fidelity on family functioning, the intervention’s mediator, and adolescent substance use. Separate models for adherence and competence each provided an adequate fit to the data, with approximately half of the pathways of primary interest (i.e., those to and from fidelity) found to be significant. These models each demonstrated different associations among variables. For adherence, results indicated that perceptions of parental involvement in schools and school SES predicted indirect adherence ratings in the expected directions. Contrary to hypotheses, school size was positively associated with direct adherence ratings, whereas indirect adherence ratings were negatively related to school performance grade and positively related to substance use. The relationship between direct adherence ratings and substance use, though not significant, was in the expected direction (i.e., negative). For competence, facilitator openness to EBIs was associated with indirect competence ratings, whereas school performance grade and school size were associated with direct competence ratings, all in the expected directions. Direct competence ratings, in turn, were negatively associated with substance use. These results have important implications for monitoring intervention fidelity as interventions like Familias Unidas move beyond T3 translation.

The most noteworthy findings in this study are related to differences observed between direct and indirect ratings of adherence and competence and their respective associations with adolescent substance use. Whereas direct ratings of competence negatively predicted substance use, indirect ratings of adherence were positively associated with this outcome. These findings speak to (1) the advantages and disadvantages of using observational vs. self-reported measures for assessing fidelity, (2) differences inherent to the measures of adherence and competence used in this study, and (3) the importance of competent intervention delivery.

Observational data are generally more accurate than self-report data [38]. As interventions are brought to scale, however, it may not be feasible to use traditional observational methods for monitoring fidelity as they are more costly and time intensive [18, 39]. Researchers have reported taking ~40 h to appropriately train observers to monitor intervention fidelity [11]. Hogue and colleagues [18] argue that reliable, resource-efficient therapist self-report methods are urgently needed to monitor implementation. As part of a family based preventive intervention delivered to inner-city adolescents at risk for substance use, these authors demonstrated high reliability between self-reported therapist ratings of fidelity and those of nonparticipant coders when using a rating system based on the number of minutes dedicated to predefined intervention targets and foci [18]. Substituting self-report measures of intervention extensiveness for those that more closely approximate “billable clinical hours” used in practice settings may thus be a potential strategy for increasing the overall utility of self-reported measures. This more objective, self-report strategy may also decrease social desirability responding, which could have accounted for an overestimation of indirect ratings of adherence in the present study. In addition to developing more reliable/valid self-report measures, future research should examine other aspects of facilitator self-report (e.g., openness to EBIs assessed at multiple time points) that might be useful for monitoring implementation.

Findings from this study also emphasize the need for more practical observational methods. One possibility for moving forward is the use of computational linguistics methods for fidelity assessment, which would automate ratings and increase the ability to monitor and provide timely supervision [40]. Indeed, a proof of concept for the use of computational linguistics has been conducted for Familias Unidas [41]. Specifically, one of the indicators of competence (“joining”) was examined in a third of family visits in this trial using a specified decision tree algorithm that categorized transcribed facilitators’ Spanish and/or English-language utterances (e.g., use of open-ended questions) as characteristic of low or high joining with families [41]. This algorithm, developed with input from Familias Unidas developers and the lead clinical supervisor, was designed to rate “what/why” questions as more favorable for joining than other types of questions and/or utterances and demonstrated high reliability (kappa = 0.83) with human observers. Use of these or similar innovative technology-based methods may reduce high costs, improve the speed with which feedback is provided to facilitators, and strengthen associations between fidelity and outcomes.

Careful consideration must also be given to the items used to measure fidelity. Current measures of fidelity are either specific to a given intervention or more global ones used across multiple interventions [39]. The measure of adherence in this study was not only intervention-specific, but also session-specific. In other words, the number and content of items was contingent on material covered during a given session. As such, adherence at one group session may not have corresponded to adherence at another group session. Cross et al. [15] showed that multiple session fidelity ratings could correct for “difficult” sessions and provide a better overall measure of delivered fidelity. Contrastingly, competence was assessed using the same four items each week. This is similar to the fidelity rating system used in the PMTO intervention, which rates the same five dimensions (i.e., knowledge of PMTO, structure, teaching, clinical process, and overall quality) across sessions [11]. As Familias Unidas continues to move along the translation stages, it may be beneficial to revise the measure of adherence such that intervention-specific content is still captured while using items that remain consistent across sessions. For example, items may be related more broadly to how well facilitators maintained session structure by following the agenda and engaging in outlined activities. This revision of items may enhance the measure’s utility and improve its predictive validity, especially for lay populations more likely to implement and monitor interventions as they are brought to scale.

Discrepant findings between direct and indirect measures of adherence and competence also highlight the important role of competent intervention delivery in producing desired study outcomes. Competent intervention delivery in this intervention is characterized by facilitators’ use of joining, group cohesion-building, and participatory learning techniques, all of which represent core process elements of Familias Unidas [20]. Beyond Familias Unidas, these findings have implications for other group-based interventions for which similar competencies are central to the success of the intervention. Specifically, if limited resources are available for monitoring fidelity, it may be important to prioritize direct ratings of competence over adherence. With regard to indirect ratings of adherence, on the other hand, findings suggest facilitator perceptions of rigid adherence to session content may actually be counterproductive to study outcomes. Barber and colleagues [42] found that moderate adherence to drug counseling was more predictive of positive outcomes than perfect adherence. Finding ways for facilitators to have flexibility within the structure of EBIs may improve the relationship between self-reported adherence and outcomes. Furthermore, achieving a better understanding of how direct and indirect ratings of adherence and competence interact in predicting outcomes is warranted. In the present study, follow-up analyses examining indirect ratings of adherence as a moderator of the relationship between direct ratings of competence and substance use were conducted. Though not found to be statistically significant, these types of analyses may provide information regarding the most and least optimal combinations of direct vs. indirect ratings of adherence and competence in future studies. Overall, special supervisory attention should be given to those facilitators who consider themselves highly competent and/or adherent but whose direct measures indicate otherwise.

Other key findings from this study are related to systems-contextual factors that impact intervention adherence and competence. While parent and adolescent nativity status and parental stress were related to family functioning at baseline, neither family functioning nor attendance at the first session were related to fidelity. Several variables at the facilitator and organizational levels, however, were found to impact direct and indirect adherence and competence ratings. These findings are generally consistent with previous literature indicating that positive provider attitudes and perceptions are positively related to intervention fidelity [23]. School size and other indicators of the school climate (i.e., SES, school performance grade), also impacted either adherence or competence [30, 31]. Contrary to hypotheses, school performance grade and size were negatively and positively related to direct ratings of adherence, respectively. These findings may be explained by the fact that 47 % of facilitators conducted sessions outside of the schools employing them as counselors and may thus not accurately reflect their work demands. Overall, knowledge of these relationships may aid in the use of more proactive technical assistance provided throughout the translation process [43]. For example, knowing in advance that facilitator openness positively impacts competence may indicate the need for tailored technical assistance provided to those scoring low on this indicator. Similarly, prioritizing technical assistance to providers at larger, lower-resourced schools may also be beneficial.

These results should be considered in light of study limitations. Substance use was assessed with self-reported vs. an objective indicator. In addition, no data were collected on other potentially important and more wide-ranging provider (e.g., personality traits, attitudes about healthcare and prevention programs, beliefs about help seeking, attributions regarding the causes of adolescent risk taking) and systems-contextual factors associated with the implementation of EBIs (e.g., organizational support for program delivery) as has been done in previous studies [44]. Finally, the predominant Hispanic subcultural group in the USA (i.e., Mexicans) was not well-represented in the current sample which limits generalizability of findings beyond Miami, FL, to the larger US Hispanic population. Despite these limitations, this study has numerous notable strengths, including the examination of factors impacting implementation of an effectiveness trial using a large sample of Hispanic parent-adolescent dyads, the use of SEM to understand complex relations among variables, and assessment of the primary outcome at 30 months post baseline.

As family centered, evidence-based preventive interventions are scaled both up and out to diverse settings, ensuring they are implemented with fidelity in the real world may maximize positive outcomes. Understanding factors associated with intervention fidelity and how fidelity relates back to key study mediators and outcomes is critical for the process of translation. This study highlights how Familias Unidas moved from T1 to T3 translation and contributes more specifically to the literature on T3 translation by examining parameters associated with the implementation of a highly replicated program with consistent positive effects across time and context. As this program of research moves to more advanced stages in the translational process, ongoing next steps involve testing both international and online adaptations of the intervention. The online adaptation, in particular, will likely be more transportable and may thus be integrated into a wider range of contexts, including primary care [45]. In addition to having important implications for researchers, these findings also offer important insights for communities and organizations looking to adopt EBIs. Beyond obtaining an understanding of the actual intervention, learning more about factors found to facilitate or impede the translation of the EBI under consideration (e.g., characteristics of facilitators, available resources, and size of the organization) as well as resource-efficient methods for monitoring fidelity may be equally as important to the success of the intervention and may aid in prioritizing resources. Overall, given many community practitioners adapt evidence-based programs to fit with their cultures, orientations, and funding, more needs to be learned about the promotion of intervention fidelity and its association with long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This was an investigator-initiated study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA025192 to Guillermo Prado, PhD; P30 DA027828 to C. Hendricks Brown) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 DA025192S1 to Guillermo Prado, PhD). The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the paper or decision to submit the paper for publication. The researchers were independent from the funders. All authors had full access to all data and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures for this study, including the informed consent process, were performed in accordance with ethical standards and protection for human subjects.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Community practitioners should learn more about factors found to facilitate or impede the translation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) and use observational methods for monitoring intervention fidelity.

Research: Researchers should exercise caution when using self-reported measures to monitor intervention fidelity and should further examine resource-efficient observational methods.

Policy: Policy makers should facilitate the process of bringing preventive EBIs to scale and ensure they are appropriately implemented through the use of observational methods for monitoring fidelity.

References

- 1.Griffin KW, Botvin GJ. Evidence-based interventions for preventing substance use disorders in adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):505–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasgow RE. Critical measurement issues in translational research. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009.

- 3.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF, Etz RS, Balasubramanian BA, Donahue KE, Leviton LC, Clark EC, Isaacson NF, Stange KC, Green LW. Fidelity versus flexibility: translating evidence-based research into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5):S381–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prado G, Pantin H. Reducing substance use and HIV health disparities among Hispanic youth in the USA: the Familias Unidas program of research. Psychosoc Interv. 2011;20(1):63–73. doi: 10.5093/in2011v20n1a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estrada, Y, Huang S, Tapia M., Velázquez MA, Pantin H, Ocasio M, Vidot D, Molleda L, Villamar J, Stepanenko BA, Brown CH, Prado G. Evaluating an efficacious drug use and sexual behavior preventive intervention in a real world setting: Results from a randomized effectiveness trial. Am J Public Health. under review.

- 6.Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, Sullivan S, Tapia MI, Sabillon E, Lopez B. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(6):914–26. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people:: progress and possibilities. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Mary Ellen O’Connell, Thomas Boat, and Kenneth E. Warner, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 8.Fishbein D, Sussman S, Ridenour T, Stahl M. The potential for transdisciplinary translational research, practice and policy to reduce individual and population level disorder burden. Translational Behavioral Medicine. under review.

- 9.Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Prado G, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental HIV prevention programs for Hispanic adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(4):545–58. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Sustaining fidelity following the nationwide PMTO™ implementation in Norway. Prev Sci. 2011;12(3):235–46. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behav Ther. 2005;36(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenwald SK, Garland AF. A review of treatment adherence measurement methods. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(1):146–56. doi: 10.1037/a0029715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(6):962–74. doi: 10.1037/a0033950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hukkelberg SS, Ogden T. Working alliance and treatment fidelity as predictors of externalizing problem behaviors in parent management training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(6):1010–20. doi: 10.1037/a0033825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross W, West J, Wyman PA, Schmeelk-Cone K, Xia Y, Tu X, Teisl M, Brown CH, Forgatch M. Observational measures of implementer fidelity for a school-based preventive intervention: development, reliability, and validity. Prevention Science. 2014: Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s11121-014-0488-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Eames C, Daley D, Hutchings J, Whitaker C, Jones K, Hughes J, Bywater T. Treatment fidelity as a predictor of behaviour change in parents attending group‐based parent training. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(5):603–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogue A, Henderson CE, Dauber S, Barajas PC, Fried A, Liddle HA. Treatment adherence, competence, and outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(4):544. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogue A, Dauber S, Henderson CE, Liddle HA. Reliability of therapist self-report on treatment targets and focus in family-based intervention. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2014;41:697–705. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0520-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence‐based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems‐contextual perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: an ecodevelopmental, parent-centered approach. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25(4):469–500. doi: 10.1177/0739986303259355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitenstein SM, Fogg L, Garvey C, Hill C, Resnick B, Gross D. Measuring implementation fidelity in a community-based parenting intervention. Nurs Res. 2010;59(3):158–65. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbb2e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prado G, Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Lupei NS, Szapocznik J. Predictors of engagement and retention into a parent-centered, ecodevelopmental HIV preventive intervention for Hispanic adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(9):874–90. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne AA, Eckert R. The relative importance of provider, program, school, and community predictors of the implementation quality of school-based prevention programs. Prev Sci. 2010;11(2):126–41. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haug NA, Shopshire M, Tajima B, Gruber V, Guydish J. Adoption of evidence-based practices among substance abuse treatment providers. J Drug Educ. 2008;38(2):181–92. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.2.f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson TD, Steele RG, Mize JA. Practitioner attitudes toward evidence-based practice: themes and challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2006;33(3):398–409. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson TD, Steele RG. Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2007;34(4):319–30. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domitrovich CE, Bradshaw CP, Poduska JM, Hoagwood K, Buckley JA, Olin S, Romanelli LH, Leaf PJ, Greenberg MT, Ialongo NS. Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: a conceptual framework. Adv School Mental Health Promotion. 2008;1(3):6–28. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2008.9715730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakker J, Denessen E, Brus‐Laeven M. Socio‐economic background, parental involvement and teacher perceptions of these in relation to pupil achievement. Educ Stud. 2007;33(2):177–92. doi: 10.1080/03055690601068345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ringwalt CL, Ennett S, Johnson R, Rohrbach LA, Simons-Rudolph A, Vincus A, Thorne J. Factors associated with fidelity to substance use prevention curriculum guides in the nation's middle schools. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(3):375–91. doi: 10.1177/1090198103030003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne AA, Gottfredson DC, Gottfredson GD. School predictors of the intensity of implementation of school-based prevention programs: results from a national study. Prev Sci. 2006;7(2):225–37. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregory A, Henry DB, Schoeny ME. School climate and implementation of a preventive intervention. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;40(3–4):250–60. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological assessment: a journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1991;3(3):438. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rio AT, Quay HC, Santisteban DA, Szapocznik J. Factor-analytic study of a Spanish translation of the revised behavior problem checklist. J Clin Child Psychol. 1989;18(4):343–50. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1804_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pantin H. Ecodevelopmental measures of support and conflict for Hispanic youth and families. Miami, FL: University of Miami School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10(2):115–29. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zelli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: a measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(3):212–23. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6(2):61–74. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237–56. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community‐based interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(2):164–73. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown CH, Mohr DC, Gallo CG, Mader C, Palinkas L, Wingood G, Prado G, Kellam SG, Pantin H, Poduska J. A computational future for preventing HIV in minority communities: how advanced technology can improve implementation of effective programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(0 1):S72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829372bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallo C, Pantin H, Villamar J, Prado G, Tapia M, Ogihara M, Cruden G, Brown CH. Blending qualitative and computational linguistics methods for fidelity assessment: Experience with the Familias Unidas preventive intervention. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2014:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Barber JP, Gallop R, Crits-Christoph P, Frank A, Thase ME, Weiss RD. Beth Connolly Gibbons M. The role of therapist adherence, therapist competence, and alliance in predicting outcome of individual drug counseling: results from the National Institute Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Psychother Res. 2006;16(02):229–40. doi: 10.1080/10503300500288951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wandersman A, Chien VH, Katz J. Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50:445–59. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klimes-Dougan B, August GJ, Lee C-YS, Realmuto GM, Bloomquist ML, Horowitz JL, Eisenberg TL. Practitioner and site characteristics that relate to fidelity of implementation: the Early Risers prevention program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40(5):467–75. doi: 10.1037/a0014623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prado G, Pantin H, Estrada Y. Integrating evidence-based interventions for adolescents into primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):488–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]