Abstract

Objective: To clarify the histopathological characteristics of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) resulting in lethal pulmonary thromboembolism (PE).

Subjects and Methods: We investigated 100 autopsy cases of PE from limb DVT. The distribution and chronology of DVT in each deep venous segment were examined. Venous segments were classified into three groups: iliofemoral vein, popliteal vein and calf vein (CV). The CV was subdivided into two subgroups, drainage veins of the soleal vein (SV) and non drainage veins of SV.

Results: Eighty-nine patients had bilateral limb DVTs. CV was involved in all limbs with DVT with isolated calf DVTs were seen in 47% of patients. Fresh and organized thrombi were detected in 84% of patients. SV showed the highest incidence of DVTs in eight venous segments. The incidence of DVT gradually decreased according to the drainage route of the central SV. Proximal tips of fresh thrombi were mainly located in the popliteal vein and tibioperoneal trunk, occurring in these locations in 63% of limbs.

Conclusions: SV is considered to be the primary site of DVT; the DVT then propagated to proximal veins through the drainage veins. Lethal thromboemboli would occur at proximal veins as a result of proximal propagation from calf DVTs.

Keywords: pulmonary thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, soleal vein, calf vein, autopsy

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) can induce a variety of clinical consequences, including venous stagnation in the leg and pulmonary thromboembolism (PE), as a result of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Among these consequences, massive PE is one of the most serious outcomes with a high mortality rate.1,2) In the majority of PE cases, the embolic source is considered to be the deep veins of the lower extremitiesy.3–6) However, the detailed incidence and distribution of leg DVT in cases of massive PE are unclear because most acute massive PE patients die suddenly without definitive diagnosis or leg examinations during their lifetime.

Autopsy investigations of leg DVT in patients with massive PE have been performed previously.4–9) However, most previous reports focused on proximal limb DVTs, which are considered to have a direct relationship to massive PE.8,9) Calf DVT has not been adequately studied using autopsy material. However, clinical investigations have shed new light on calf DVT as a possible embolic source leading to PE.10–15)

We have previously studied medicolegal autopsy cases of patients who died of massive PE using histopathological methods.1,2,16,17) Among them, we reported a high frequency of DVT in calf veins, especially in the soleal vein and related drainage veins.16) However, we could not perform statistical analysis on the distribution and chronology of DVT in each deep venous segment in our previous study. Moreover, the location of residual fresh thrombi in the limbs, which would be useful information in the clinical setting was not considered in our previous study. Therefore, we increased the number of the cases to 100 from 60 cases in the present study and performed detailed statistical analysis.

The present study was carried out to clarify the histopathological characteristics of limb DVT resulting in lethal massive PE. For this purpose, we examined bilateral limb deep veins from patients who died of massive PE. The detailed distribution and chronology of DVT in each deep venous segment was histopathologically evaluated. Based on our results, the suspected etiology of limb DVT from occurrence to growth resulting in massive PE is proposed.

Subjects and Methods

Selection of patients

One-hundred patients who died from acute massive PE and were identified as having DVTs of the lower extremities by autopsy were enrolled in the study. This study contained 55 patients who were reported in our previous study.16) The patients included 41 men and 59 women, and their mean age (±SD) was 58.5 (±16.3) years. Cause of death was diagnosed based on the results of medicolegal autopsies performed at the Tokyo Medical Examiner’s Office between August 1999 and February 2007. During the same period as the present study, 18992 medicolegal autopsies were performed; 347 resulted in a diagnosis of PE. Medicolegal autopsy was performed to determine the patients’ cause of sudden unexpected death. The patients included 85 outpatients who were found dead at home or died soon after emergency arrival to the hospital. The remaining patients comprised 15 in-hospital patients; 10 had psychiatric disorder, three had PE after surgery, two had leg injury without operation, respectively. Patients who had pre-fatal examinations or any treatment for VTE were excluded from this study. PE patients who did not receive leg investigations at autopsy and patients in whom limb DVT could not be confirmed, despite autopsy investigations, were also excluded. We experienced two patients who did not have limb DVT despite a detailed leg examination during this study period; one of these patients had upper limb DVT due to angioma. Another patient had isolated internal iliac vein thrombosis after a caesarean operation. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Tokyo Medical Examiner’s Office.

Autopsy investigation of limb DVT

An autopsy investigation of limb DVT was performed as follows. After confirmation of massive PE by autopsy, the iliofemoral veins (iliac vein and femoral vein) were opened for macroscopic examination. Histopathological sections were collected if DVT was found. A midline incision of the back side of the leg was then made from the knee joint to the ankle. The popliteal vein and five segments of the calf vein were extracted with the calf muscles as one block for formalin fixation (Fig. 1A). All venous segments of the calf vein included three crural branches (posterior tibial vein, peroneal vein, and the anterior tibial vein) and two calf muscular veins (gastrocnemius vein and soleal vein) (Figs. 1B, 1C), and the popliteal vein was observed in serial 5-mm transverse sections. Every fifth section of each of the described venous segments was collected for processing into paraffin blocks. Histological sections were cut and stained using hematoxylin and eosin, elastica van Gieson, and phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin methods. DVTs were classified into two types (fresh thrombi and organized thrombi) based on histopathological chronology, referring to the results of a previous investigation.7) Fresh thrombi are composed of erythrocytes, platelets and fibrin. The proximal tip of fresh thrombi indicated residual fatal thromboemboli or the leading point of an embolus (Fig. 1D). Organized thrombi were eccentric collagen or elastin elements that completely replace the erythrocytes and fibrin, which indicate a previous history of DVT (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

A representative case. (A) Extracted popliteal vein and calf veins with calf muscle. The arrows indicate each calf venous segment. (B) Transverse sections of gastrocnemius muscle. Intramuscular thrombi were macroscopically observed (arrows). (C) Transverse sections of soleal muscle. Intramuscular thrombi were macroscopically observed (arrows). (D) Histological section of soleal muscle stained by the elastica van Gieson method (magnification ×1). One soleal artery accompanied by a pair of soleal veins was observed. One soleal vein was occluded by organized thrombi (left arrow) and the other soleal vein was dilated with fresh thrombi (right arrow).

Classification of limb deep venous segments for assessment of DVT

The laterality and distributions of DVT in each limb were examined. Limb deep venous segments were divided into three main groups: the iliofemoral veins, popliteal vein and calf veins. The iliofemoral veins and popliteal vein were also considered together as one group called the proximal veins. The incidence and chronology of DVT in the three venous groups were investigated.

The incidence of DVT in each of eight leg deep venous segments including three segments of proximal veins and five of calf veins were observed. The calf venous segments were further divided into two subgroups based on blood flow from the central soleal vein, as shown by our previous study.16) The posterior tibial vein, peroneal vein and soleal vein were defined as a subgroup called the drainage veins of the soleal vein. The anterior tibial vein and the gastrocnemius vein were defined as another subgroup called the non-drainage veins of the soleal vein.

Finally, we classified limb deep veins into four groups, namely, the iliofemoral veins, popliteal vein, tibioperoneal trunk and soleal veins, to detect the locations of the proximal tips of fresh thrombi.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Non-ordinal categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test. The laterality and distributions of limb DVTs in each deep venous segment were assessed by multiple logistic regression using dummy variables. The results are presented as estimated odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests of significance were two-tailed.

Results

Distribution and chronology of limb DVT in 100 patients who died from massive PE

DVT was detected in 189 limbs (95%) among 200 limbs of 100 massive PE patients. Eighty-nine patients had bilateral DVTs, whereas seven patients had unilateral DVTs in the right limb and four patients had unilateral DVTs in the left limb. The chronology of DVTs of five patients was composed only of fresh thrombi, and those of ten patients were composed only of organized thrombi. The other 85 patients had both fresh and organized thrombi.

Distribution and chronology of DVT in the iliofemoral vein, popliteal vein and calf vein

Calf veins were involved in all 189 limbs with DVTs. Among them, isolated calf DVT occurred in 47% of patients (Table 1). Isolated iliofemoral or popliteal vein DVT was not observed.

Table 1.

Laterality and distribution of deep vein thromboses in the iliofemoral vein, popliteal vein and calf vein among 189 legs of individuals with fatal pulmonary thromboembolism

| Segments | Limbs, no. (%) | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|---|

| IF + pop + calf | 33 (17%) | 15 | 18 |

| Pop + calf | 65 (34%) | 32 | 33 |

| Calf | 89 (47%) | 45 | 44 |

| IF + calf | 2 (1%) | 1 | 1 |

| Total limbs, no. | 189 | 93 | 96 |

IF: iliofemoral vein; pop: popliteal vein; calf: calf vein

Most of the thrombi in iliofemoral veins were fresh thrombi. The popliteal vein also showed a relatively higher incidence of fresh thrombi than did calf veins. By contrast, the majority of calf DVTs contained both fresh and organized thrombi (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chronology of deep vein thromboses in the iliofemoral vein, popliteal vein and calf vein

| Segments | Total limb no | Limb no (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT | FT + OT | OT | ||

| Iliofemoral vein | 35 | 29 (83%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (12%) |

| Popliteal vein | 98 | 61 (62%) | 16 (16%) | 21 (21%) |

| Calf vein | 189 | 33 (17%) | 117 (62%) | 39 (21%) |

| p-value | <.0001 | <.0001 | .37 | |

FT: fresh thrombi; OT: organized thrombi

Laterality and distribution of limb DVTs in each deep venous segment

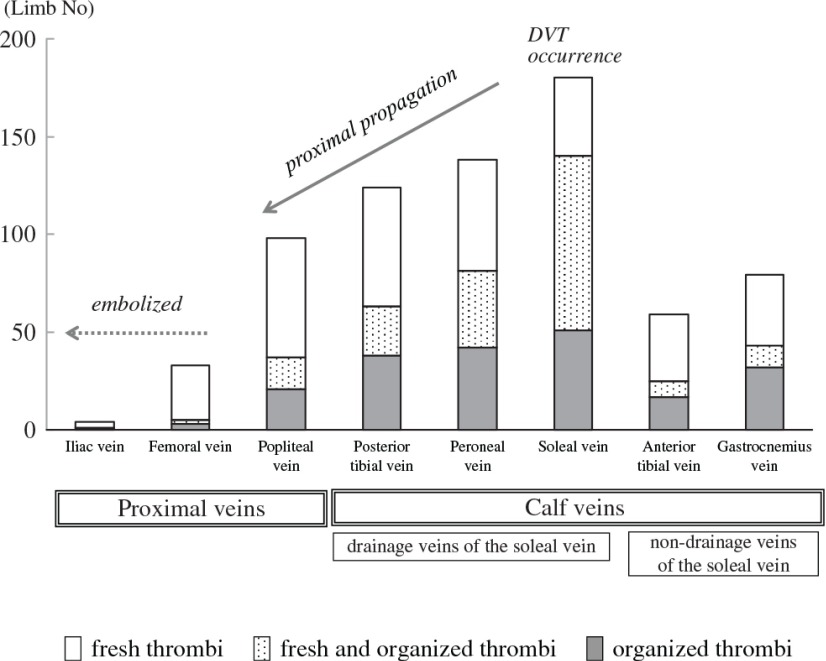

The laterality and distribution of DVTs showed similar tendencies in fresh and organized thrombi. The incidence of DVT was highest in the soleal vein and gradually decreased according to the drainage route of the central soleal vein in the following order: the peroneal vein, the posterior tibial vein and the popliteal vein (Fig. 2). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the detection rate of DVT in all deep venous segment was significantly high in the soleal vein and the odds ratio was relatively higher at the drainage veins of the soleal vein than the non-drainage veins of the soleal vein. The iliofemoral veins showed relatively lower odds ratios of DVT than the other veins, and rarely had organized thrombi.

Fig. 2.

Distribution and chronology of DVTs in eight deep venous segments in 189 limbs and the suspected mechanism of VTE resulting in lethal PE. DVT: deep vein thrombosis; VTE: venous thromboembolism; PE: pulmonary thromboembolism

There was no significant laterality of leg DVT in fresh and organized thrombi (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of multiple logistic analysis of the venous segment and laterality of fresh thrombi and organized thrombi

| Fresh thrombi | Organized thrombi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Venous segment | ||||

| Proximal vein | ||||

| Iliac vein | 0.01 (0.003–0.03) | <.0001 | 0.002 (0.003–0.02) | <.0001 |

| Femoral vein | 0.10 (0.06–0.16) | <.0001 | 0.01 (0.004–0.03) | <.0001 |

| Popliteal vein | 0.34 (0.23–0.52) | <.0001 | 0.10 (0.06–0.15) | <.0001 |

| Calf vein | ||||

| Drainage veins of the soleal vein | ||||

| Posterior tibial vein | 0.41 (0.28–0.62) | <.0001 | 0.20 (0.13–0.30) | <.0001 |

| Peroneal vein | 0.51 (0.34–0.76) | .001 | 0.29 (0.19–0.44) | <.0001 |

| Soleal vein | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Non-drainage veins of the soleal vein | ||||

| Anterior tibial vein | 0.15 (0.09–0.23) | <.0001 | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) | <.0001 |

| Gastrocnemius vein | 0.17 (0.11–0.26) | <.0001 | 0.12 (0.07–0.18) | <.0001 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Left leg | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Right leg | 1.13 (0.90–1.43) | .29 | 1.18 (0.91–1.54) | .21 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence intervel

Proximal tips of residual fresh thrombi

DVT containing fresh thrombi was detected in 155 limbs. Among them, one limb was excluded from analysis because the location of the limb’s proximal tips of residual fresh thrombi was in the anterior tibial vein, which is not one of our four defined locations. The proximal tips of fresh thrombi were located in the iliofemoral veins in 20%, in the popliteal vein in 32%, in the tibioperoneal trunk in 31%, and in the soleal vein in 17% of patients.

Discussion

Clinical significance of calf DVT in patients who died from massive PE

This study showed a remarkably high incidence of calf DVT in acute PE patients. The calf vein was involved in all limbs with DVT, 47% of which had isolated calf DVT. Clinical investigations paid little attention to calf DVT until an improvement in venous imaging technology enabled routine examinations of in the calf vein. The reported incidence of isolated calf DVT in PE patients is relatively low; it is 14% by ultrasound,18) 20% by venography19) and 13%–15% by autopsy.5,6) These previous investigations of calf veins mainly focused on a part of the crural veins such as the peroneal vein or the posterior tibial vein; therefore, calf muscular veins have not been adequately investigated.9,20,21) Investigations of whole calf venous segments including calf muscular veins have increased the detection rate of calf DVT. Nichimi et al. showed that 64% of VTE patients had calf vein involvement and that 48% of VTE patients had isolated calf DVT.19) Labropoulos et al. reported that 40% of cases of isolated calf DVT would have been missed without investigation of calf muscular veins.22) These findings indicate that detailed examination of calf veins, including calf muscular veins, is needed to determine the hidden presence of calf DVT.

High detection rate of DVT in the soleal vein and its drainage veins

In our study, among the calf veins, the soleal vein showed the highest incidence of DVT, with fresh and organized thrombi. Many clinical and autopsy reports have indicated that the soleal vein is the most frequent site of isolated calf DVT, especially in cases of single vein involvement.8,10,11,14,23–25) One reason for the high incidence of DVT in the soleal vein may be its dilated nature of the soleal vein, which increases with age.23) We suspected that another reason could be the anatomical characteristics of the soleal muscle and the soleal vein.16) The soleal vein is prone to a stagnant, thrombotic status in cases of immobilization without constriction of the soleal muscle. Therefore, the soleal vein tends to be a site of occurrence of limb DVT.16)

In the current study, the incidence of limb DVT was highest in the soleal vein, with a decreasing incidence in the order of the peroneal vein, the posterior tibial vein, and the popliteal vein. We did not investigate the detailed distribution of soleal vein thrombi among the three branches in all the cases of this study. However, the distribution of thrombi among the soleal venous branches, which was investigated in approximately one-third of the cases in this study, showed that the central soleal vein had the highest incidence of DVT (data not shown). Ohgi reported that isolated soleal vein thrombosis was frequently located at the central soleal vein.26) Therefore, the drainage veins of the central soleal vein could become a route for propagation of DVT. A high incidence of limb DVT in the soleal and peroneal veins and proximal propagation involving these drainage veins has been shown by previous investigations,22,25,27) which are consistent with our results.

By contrast, our results and the results of previous studies have shown that the non-drainage veins of the soleal vein have a relatively lower incidence of DVT, even in the calf veins.18,22,24) Such a discrepancy in calf venous segments has not been previously described, and the reason for this finding is unclear. We speculate that the non-drainage veins of the soleal vein are not thrombosed until soleal vein thrombosis is propagated and fully thrombosed at the popliteal trunk, resulting in retrograde propagation to the non-drainage veins.17) Our results strongly suggest the existence of a pathological relationship between development of calf DVT and anatomical characteristics relating to the soleal vein.

Proximal propagation of calf DVT

An autopsy study indicated that approximately 60% of cases of massive PE result from recurrent DVT.7) We reported that 92% of patients who died from acute PE had a recurrent history of PE.2) The present study also showed that 85% of cases had fresh and organized thrombi, suggesting a recurrent history of DVT. Previous DVT detected as organized thrombi were predominantly found in the calf veins. We consider that limb DVTs in patients who died from massive PE primarily occurs in the calf veins and then propagate to the proximal veins.

We speculated that propagated proximal thrombi from calf DVT tend to form free-floating thrombi.1,16,17) Free-floating thrombi have little attachment to the venous wall and are anchored by distal organized thrombi. Therefore, they can rapidly grow without leading to leg symptoms caused by vascular occlusion. By contrast, primary proximal thrombi, which are mainly caused by a pelvic mass or May-Thurner syndrome, are prone to grow as occlusive thrombi inducing leg symptoms.2) The incidence of isolated pelvic DVT with PE patients is 9.8%19)–30%.5) However, isolated pelvic DVT was has seldom been found in our institution. One of the suspected reasons for this low observed incidence of isolated pelvic DVT is the low incidence of in-hospital patients in medicolegal autopsy. Additionally, none of our cases had anatomical obstructions of the iliac veins known as venous spurs, in this study. Therefore, propagated proximal thrombi are associated with a higher risk of PE than primary proximal DVT. This is the reason why large life-threatening embolic source can grow in the limb veins with only a few leg symptoms.

Embolic source of massive PE

Many clinical and autopsy studies have noted the significance of proximal DVTs in cases of massive PE.5,6,12,18,20) In the present study, approximately half of the proximal tips of residual fresh thrombi were located in the proximal veins. We believe that the embolic source of lethal PE is located at the nearest proximal group of veins that are continuous with the location of the proximal tips of residual fresh thrombi. Therefore, the finding of residual thrombi in the tibioperoneal trunk (31% out of 49% of the patients who had proximal tips of thrombi in calf DVT) suggested the existence of lethal embolic material in the proximal veins as well as in the iliofemoral vein and popliteal vein. Our finding indicated that lethal embolic material was dominantly located at proximal veins.

Some investigators have reported that as many as 74%3)–75%8) of the proximal tips of limb thrombi are located in proximal veins in PE patients. Moser and LeMoine reported that patients with isolated calf DVTs have no complications of PE; However, approximately half of patients with both proximal and calf DVTs are affected by PE.12) Our results also support the importance of proximal DVT as a probable source of massive PE. For the reasons described above, proximal DVTs are considered to result from proximal propagation from calf DVTs.

Possible mechanism of calf DVT resulting in massive PE

Based on these results, we suggest a possible mechanism for lower limb DVT resulting in lethal massive PE (Fig. 2, Supplemental Figure). First, DVT originates in the soleal vein mainly due to excessive venous stasis. The calf DVT then propagates to the proximal veins through the drainage veins of the soleal vein. Propagated proximal DVTs form free-floating thrombi, which finally become detached by knee flex or other triggers, producing large thromboemboli that occlude the pulmonary artery.

Clinical implications

The best treatment strategy for isolated calf DVTs, especially isolated muscular vein thromboses, requires clarification.11,27) Previous investigations have indicated that isolated calf DVTs have better prognosis, with a relatively lower incidence of complications of proximal propagation (3%–32% of cases10,13–15,24,27,28,29)) and PE (2%–21% of cases10,11,13–15,30)). However, an epidemiological study revealed that the prognosis of patients with bilateral distal DVT is as poor as that of patients with bilateral proximal DVT in terms of mortality and the recurrence rate of DVT.28) Another study reported that the incidence of associated VTE related to isolated calf muscular DVTs is dramatically reduced with therapeutic anticoagulation.29) Our results emphasize the clinical importance of calf DVTs, especially those in the soleal vein and its drainage veins, from the viewpoint of lethal PE prophylaxis.

Study limitations

This study investigated only patients with massive PE because of the limitation that this was a retrospective study of autopsy examinations of deep veins in the legs in our institution. A complete examination of leg veins requires additional incisions for both legs, and this sometimes causes cosmetic problems. Therefore, invasive autopsy examinations of vein in the legs are permitted only for diagnostic necessity such as in the case of lethal massive PE or leg fractures.

This was a retrospective study of massive lethal PE. Therefore, clinical features of the occurrence and growth of leg DVT at an early stage or the effectiveness of clinical prophylaxis could not be determined from our data. Management for isolated calf DVT cannot be established until the propagation rate according to the patients’ risks is clarified by a clinical prospective study. However, we believe that detailed characteristics of leg DVT with histopathological chronology are sufficient to provide a possible mechanism of leg DVT from its occurrence to embolization with variable clinical implications.

Conclusion

Patients with lethal massive PE show a high incidence of DVT in calf veins. The distribution and chronology of limb DVTs in each venous segment show that the soleal vein would be the primary site of calf DVTs, and that soleal vein thromboses propagate through the drainage veins of the soleal vein. Lethal thromboemboli are thought to form as free-floating DVTs at proximal veins as a result of proximal propagation of calf DVTs. These findings suggest that, in the clinical setting, careful observation of the soleal vein and its drainage veins is important for primary prophylaxis against lethal PE.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Study conception: AR

Data collection: all authors

Analysis: AR

Investigation: all authors

Writing: AR

Critical review and revision: all authors

Final approval of the article: all authors

Accountability for all aspects of the work: all authors

Acknowledgment

We sincerely appreciate the advice and expertise of late Dr. Masahito Sakuma.

References

- 1).Ro A, Kageyama N, Tanifuji T, et al. Pulmonary thromboembolism: overview and update from medicolegal aspects. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2008; 10: 57-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Ro A, Kageyama N, Tanifuji T, et al. Autopsy-proven untreated previous pulmonary thromboembolism: frequency and distribution in the pulmonary artery and correlation with patients’ clinical characteristics. J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9: 922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Girard P, Musset D, Parent F, et al. High prevalence of detectable deep venous thrombosis in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 1999; 116: 903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Hunter WC, Krygier JJ, Kennedy JC. Etiology and prevention of thrombosis of the leg deep veins: a study of 400 cases. Surgery 1945; 17: 178-90. [Google Scholar]

- 5).Giachino A. Relationship between deep-vein thrombosis in the calf and fatal pulmonary embolism. Can J Surg 1988; 31: 129-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Sevitt S, Gallagher N. Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A clinico-pathological study in injured and burned patients. Br J Surg 1961; 48: 475-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Raeburn C. The natural history of venous thrombosis. Br Med J 1951; 2: 517-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Havig O. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. An autopsy study with multiple regression analysis of possible risk factors. Acta Chir Scand Suppl 1977; 478: 1-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).McLachlin J, Paterson JC. Some basic observations on venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1951; 93: 1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Kakkar VV, Howe CT, Flanc C, et al. Natural history of postoperative deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1969; 2: 230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Ohgi S, Tachibana M, Ikebuchi M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with isolated soleal vein thrombosis. Angiology 1998; 49: 759-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Moser KM, LeMoine JR. Is embolic risk conditioned by location of deep venous thrombosis? Ann Intern Med 1981; 94: 439-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Labropoulos N, Kang SS, Mansour MA, et al. Early thrombus remodelling of isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002; 23: 344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Lohr JM, Kerr TM, Lutter KS, et al. Lower extremity calf thrombosis: to treat or not to treat? J Vasc Surg 1991; 14: 618-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Masuda EM, Kessler DM, Kistner RL, et al. The natural history of calf vein thrombosis: lysis of thrombi and development of reflux. J Vasc Surg 1998; 28: 67-73; discussion 73-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Kageyama N, Ro A, Tanifuji T, et al. Significance of the soleal vein and its drainage veins in cases of massive pulmonary thromboembolism. Ann Vasc Dis 2008; 1: 35-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Ro A, Kageyama N, Tanifuji T, et al. The mechanism of thrombi formation, propagation and embolization of calf-type deep vein thrombosis resulting in massive pulmonary thromboembolism. Jpn J Phlebol 2006; 17: 197-205. [in Japanese with English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Elias A, Colombier D, Victor G, et al. Diagnostic performance of complete lower limb venous ultrasound in patients with clinically suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2004; 91: 187-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Nchimi A, Ghaye B, Noukoua CT, et al. Incidence and distribution of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis at indirect computed tomography venography in patients suspected of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost 2007; 97: 566-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Monreal M, Ruíz J, Olazabal A, et al. Deep venous thrombosis and the risk of pulmonary embolism. A systematic study. Chest 1992; 102: 677-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Ouriel K, Green RM, Greenberg RK, et al. The anatomy of deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity. J Vasc Surg 2000; 31: 895-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Labropoulos N, Webb KM, Kang SS, et al. Patterns and distribution of isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg 1999; 30: 787-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Kerr TM, Cranley JJ, Johnson JR, et al. Analysis of 1084 consecutive lower extremities involved with acute venous thrombosis diagnosed by duplex scanning. Surgery 1990; 108: 520-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Lohr JM, James KV, Deshmukh RM, et al. Calf vein thrombi are not a benign finding. Am J Surg 1995; 170: 86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Nicolaides AN, Kakkar VV, Field ES, et al. The origin of deep vein thrombosis: a venographic study. Br J Radiol 1971; 44: 653-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Ohgi S, Ohgi N. Relation between Isolated Venous Thrombi in Soleal Muscle and Positive Anti-Nuclear Antibody. Ann Vasc Dis 2012; 5: 321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Macdonald PS, Kahn SR, Miller N, et al. Short-term natural history of isolated gastrocnemius and soleal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg 2003; 37: 523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Parisi R, Visonà A, Camporese G, et al. Isolated distal deep vein thrombosis: efficacy and safety of a protocol of treatment. Treatment of Isolated Calf Thrombosis (TICT) Study. Int Angiol 2009; 28: 68-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Lautz TB, Abbas F, Walsh SJ, et al. Isolated gastrocnemius and soleal vein thrombosis: should these patients receive therapeutic anticoagulation? Ann Surg 2010; 251: 735-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Gillet JL, Perrin MR, Allaert FA. Short-term and mid-term outcome of isolated symptomatic muscular calf vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 513-9; discussion 519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]