Abstract

In biological energy conversion, cross-membrane electron transfer often involves an assembly of two hemes b. The hemes display a large difference in redox midpoint potentials (ΔEm_b), which in several proteins is assumed to facilitate cross-membrane electron transfer and overcome a barrier of membrane potential. Here we challenge this assumption reporting on heme b ligand mutants of cytochrome bc1 in which, for the first time in transmembrane cytochrome, one natural histidine has been replaced by lysine without loss of the native low spin type of heme iron. With these mutants we show that ΔEm_b can be markedly increased, and the redox potential of one of the hemes can stay above the level of quinone pool, or ΔEm_b can be markedly decreased to the point that two hemes are almost isopotential, yet the enzyme retains catalytically competent electron transfer between quinone binding sites and remains functional in vivo. This reveals that cytochrome bc1 can accommodate large changes in ΔEm_b without hampering catalysis, as long as these changes do not impose overly endergonic steps on downhill electron transfer from substrate to product. We propose that hemes b in this cytochrome and in other membranous cytochromes b act as electronic connectors for the catalytic sites with no fine tuning in ΔEm_b required for efficient cross-membrane electron transfer. We link this concept with a natural flexibility in occurrence of several thermodynamic configurations of the direction of electron flow and the direction of the gradient of potential in relation to the vector of the electric membrane potential.

Keywords: cytochrome, electron transfer, oxidation-reduction (redox), photosynthesis, respiratory chain, heme iron ligation

Introduction

Redox midpoint potential (Em) is a key property of any redox active cofactor in proteins. It regulates biological functions via thermodynamic and kinetic control of electron exchange reactions. Because these reactions must take place in a variety of cellular compartments, both outside and inside the biological membrane, the structures of redox proteins have evolved to meet physicochemical requirements of these various environments to achieve assemblies that secure functionally competent Em values.

Within the group of cytochromes, molecular factors that modulate Em include types of heme axial ligation (1–3). The residues that are most commonly recruited as axial ligands for the heme iron are His and/or Met (4). A binding of hemes b within the membranous proteins is accomplished by an assembly of transmembrane α-helices that provide His axial ligands for the heme-iron. In fact, the heme binding α-helix bundle represents a common motif of several bioenergetic complexes (5–7). It has even been used as a prototype to construct human-made versions of heme binding proteins (protein maquettes) (8–10).

The α-helix bundle can bind one or two hemes b. In several proteins, an assembly of two b type hemes, each facing different sides of the membrane, supports electron transfer across biological membranes crucial for energy conservation in many systems. Intriguingly, the two hemes differ largely in their redox midpoint potentials (the Em difference, ΔEm_b, is typically in the range of 100 mV); however, the thermodynamic rationale behind the existence of ΔEm_b remains unclear. This is because no general rule for the direction of ΔEm_b with respect to the direction of the electric field generated by the membrane potential or the direction of physiological electron transfer is evident (Fig. 1).

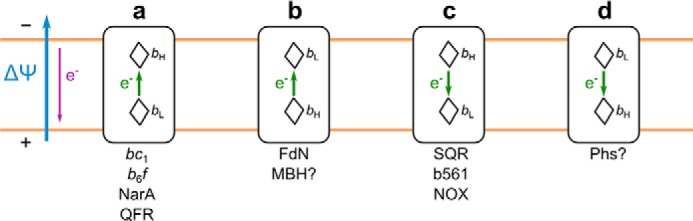

FIGURE 1.

Possible thermodynamic configurations for cross-membrane electron transfer in cytochromes b. a, electron is transferred against ΔΨ and involves energetically favorable reduction of heme bH by heme bL. b, electron is transferred against ΔΨ and additionally involves energetically unfavorable reduction of heme bL by heme bH. c, energetically unfavorable reduction of heme bL by heme bH is facilitated by ΔΨ. d, energetically favorable reduction of heme bH by heme bL is additionally facilitated by ΔΨ. bL and bH denote low potential and high potential heme, respectively. The blue arrow refers to ΔΨ (membrane electric potential); the purple arrow indicates the direction of ΔΨ-induced electron transfer; and the green arrows indicate direction of electron transfer between hemes. Configuration a can be found in cytochrome bc1 (11, 12), cytochrome b6f (37), nitrate reductase A (NarA) (39, 40), and fumarate reductase (QFR) (41, 42); configuration b can be found in formate dehydrogenase N (FdN) (40, 43) and perhaps in membrane-bound [Ni-Fe] hydrogenase (MBH) (45, 46); configuration c can be found in succinate dehydrogenase (SQR) (47, 48), cytochromes b561 (b561) (52–54), and NADPH oxidase (NOX) (51); and configuration d probably exists in thiosulfate reductase (Phs) (55).

The cytochrome b subunit of cytochrome bc1 (mitochondrial complex III) is a well known example of a protein supporting cross-membrane electron transfer by using an assembly of two hemes b, named heme bH and heme bL, where subscripts H and L refer to high and low potential, respectively (for recent reviews see Refs. 11 and 12). During the catalytic cycle, the electron transfer from heme bL to heme bH connects the quinol oxidation site (Qo)2 and the quinone reduction site (Qi). In addition, in dimeric structure of an enzyme, intermonomer electron transfer parallel to the membrane plane involving two hemes bL is possible (13–16). In living cells, the cross-membrane electron flow from heme bL to heme bH may face the barrier of the membrane potential (Fig. 1a). Thus, the fact that electrons are transferred from the cofactor of lower Em to the cofactor of higher Em provided a basis for a general assumption that ΔEm_b is one of the factors that facilitate cross-membrane electron transfer and perhaps is important in overcoming the barrier of potential (17, 18). However, the contribution of ΔEm_b to the overall electron flow has not been verified experimentally. Prerequisites for such verification are variants of cytochrome bc1 with large changes in the Em of hemes b and, consequently, large changes in ΔEm_b. However, the mutations of cytochrome b tested so far either had a relatively small effect on the Em of hemes b (19, 20) or resulted in the absence of the heme (21, 22).

Here we mutated the native bis-His coordination pattern for heme bL and/or heme bH into the His-Lys pattern, to our knowledge, providing the first His-Lys coordinated hemes b in a transmembrane protein. The hemes remain low spin as in a native enzyme but have markedly elevated Em values and thus effectively modulate ΔEm_b: an increase in the Em of heme bH by 50 mV increased ΔEm_b setting the Em of heme bH above the Em of the quinone pool in the membrane, whereas an increase in the Em of heme bL by 155 mV decreased ΔEm_b to the point that the two hemes b were almost isopotential. This provided an unprecedented set of large changes in ΔEm_b for functional testing. The results offer a new perspective toward understanding the natural engineering of the cross-membrane electron transfer in cytochromes b.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

Rhodobacter capsulatus and Escherichia coli (HB101, DH5α) were grown in liquid or solid MPYE (mineral-peptone-yeast extract) and LB (Luria Bertani) media, at 30 and 37 °C, respectively, supplemented with appropriate antibiotics as needed. Respiratory growth of R. capsulatus strains was achieved at 30 °C in the dark under semiaerobic conditions. Photosynthetic growth abilities of mutants were tested on MPYE plates using anaerobic jars (GasPakTM EZ Anaerobe Container System; BD Biosciences) at 30 °C under continuous light. The R. capsulatus strains used were: pMTS1/MTRbc1 which overproduces wild-type cytochrome bc1 from the expression vector pMTS1 (contains a copy of petABC operon coding for all three subunits of cytochrome bc1), and MTRbc1 which is a petABC operon deletion background (23). The mutagenized pMTS1 derivatives were introduced to R. capsulatus MTRbc1 via triparental crosses as described (23). Plasmid pPET1 (a derivative of pBR322 containing a wild-type copy of petABC) was used as a template for PCR and in some of the subcloning procedures.

Construction of Lys Mutants

Spontaneous Ps+ revertant of the H212N mutant originally described in Ref. 22 was obtained on MPYE plate containing tetracycline after ∼7 days of cultivation under photosynthetic conditions. The DNA sequence analysis of the plasmid DNA isolated from the revertant strain revealed a single base pair change replacing the mutated Asn into Lys at position 212 of cytochrome b. The XmaI/SfuI fragment containing the reversion (mutation H212K), and no other mutations was exchanged with its counterpart on expression vector pMTS1 carrying the wild-type copy of the petABC operon. Expression of this vector in the MTRbc1 background strain confirmed that cells bearing single mutation H212K display the photosynthetically competent Ps+ phenotype. The Ps+ reversion H212K occurred also in the double mutant A181T/H212N cultivated on MPYE plate containing kanamycin (in this case H212N in the cytochrome b subunit was accompanied by a mutation A181T in cytochrome c1 described originally in Ref. (24)). Because A181T/H212N, unlike original H212N, contained cytochrome b already equipped with the Strep-tag II attached to its carboxyl end, the plasmid obtained from the revertant of A181T/H212N was used to construct the mutants used in further analysis. First, the XmaI/SfuI fragment containing the reversion (H212K) and the sequence coding for Strep-tag II (ST), and no other mutations were exchanged with its counterpart on expression vector pMTS1 carrying the wild-type copy of the petABC operon. This created pMTS1-ST-H212K. Second, the same XmaI/SfuI fragment was cloned into pPET1 creating pPET1-ST-H212K. Mutation H198K and the double mutation H212K/H198K were constructed by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene using pPET1-ST (25) and pPET1-ST-H212K plasmids as templates, respectively, and the mutagenic forward H198K-F (5′-GGGCAGCAGATATTTCAGCGAGAAGAAGCGG-3′) and reverse H198K-R (5′-TTCTTCTCGCTGAAATATCTGCTGCCCTTCG-3′) oligonucleotides. After sequencing, XmaI/SfuI fragments of pPET1 plasmids bearing the desired mutations, and no other mutations were exchanged with their wild-type counterparts in pMTS1. This created the plasmids pMTS1-ST-H198K and pMTS1-ST-H212K/H198K. Plasmids pMTS1-ST-H212K, pMTS1-ST-H198K, and pMTS1-ST-H212K/H198K were inserted into R. capsulatus MTRBC1 cells, creating mutants H212K, H198K, and H212K/H198K, respectively. These mutants are listed in Table 1. In each case, the presence of introduced mutations was confirmed by sequencing the plasmid DNA reisolated from the mutated R. capsulatus strains.

TABLE 1.

Selected properties of wild-type and Lys mutants

| Form of bc1 | Phenotype |

Em7 |

EPR gz value |

Rates of hemes b reduction |

Steady-state activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bL | bH | bL | bH (+antimycin) | pH 6 | pH 7 | pH 9 | |||

| mV | s−1 | s−1 | |||||||

| WT | Ps+ | −92 | 80 | 3.78 | 3.44 (3.47) | 566 | 1051 | 1791 | 149 ± 7 |

| H212K | Ps+ | −86 | 130 | 3.78 | 3.22/3.15 (3.26) | 479 | 822 | 121 ± 6 | |

| H198K | Ps+ | 65 | 58 | 3.22 | 3.44 (3.47) | 392 | 770 | 1506 | 118 ± 5 |

| H212K/H198K | Ps+ | ∼72 | ∼3.2 | ∼3.2 (∼3.24) | 420 | 706 | 1548 | 91 ± 6 | |

Isolation of Membranes and Proteins

Chromatophore membranes were isolated from R. capsulatus as described previously (26). The cytochrome bc1 complexes were isolated from detergent-solubilized chromatophores by affinity chromatography using the procedure described previously (27). SDS-PAGE of purified complexes was performed as described before (28).

Optical and EPR Spectroscopy

Optical spectra measurements of isolated complexes and determination of protein concentration were performed on UV-2450 Shimadzu spectrophotometer. Cytochrome bc1 samples were suspended in 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 0.01% (m/m) dodecyl maltoside, and 1 mm EDTA, an appropriate amount of ferricyanide was added to fully oxidize complexes; then solid ascorbate and solid sodium dithionite were added to reduce samples, and spectra were recorded right after oxidation and after each step of reduction. Concentration of cytochrome bc1 was determined as described (26). EPR measurements were performed on Bruker Elexys E580 spectrometer. X-band CW-EPR spectra of hemes were measured at 10 K, using SHQE0511 resonator combined with ESR900 Oxford Instruments cryostat unit, using 1.595 mT modulation amplitude, and 1.543 milliwatt of microwave power. For EPR measurements, cytochrome bc1 samples were dialyzed against 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 20% glycerol (v/v), 0.01% (m/m) dodecyl maltoside, and 1 mm EDTA. Final concentration of cytochrome bc1 in EPR samples was 50 μm. Antimycin A was used in 5-fold molar excess over the concentration of cytochrome bc1.

Redox Potentiometry

Midpoint potentials of hemes b were determined by dark equilibrium redox titrations on chromatophores according to the method described in Ref. (29). Chromatophores were suspended in argon-equilibrated 50 mm MOPS buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mm KCl and 1 mm EDTA. Immediately before the titration, the following redox mediators were added: 100 μm tetrachlorohydroquinone, 100 μm 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl phenylenediamine (Em7 260 mV), 100 μm 1,2-naphtoquinone-4-sulfonate (Em7 210 mV), 100 μm 1,2-naphtoquinone (Em7 130 mV), 50 μm phenazine methosulfate (Em7 80 mV), 50 μm phenazine ethosulfate (Em7 50 mV), 100 μm duroquinone (Em7 5mV), 30 μm indigotrisulfonate (Em7 = −90 mV), 100 μm 2-hydroxy-1,4-napthoquinone (Em7 = −152 mV), 100 μm anthroquinone-2-sulfonate (Em7 = −225 mV), and 100 μm benzyl viologen (Em7 = −374 mV). Dithionite and ferricyanide were used to adjust ambient redox potential. During the titrations, samples of 150–200 μl were taken and transferred to EPR tubes anaerobically and frozen by immersion into cold ethanol. The Em7 values of hemes b were determined by fitting the amplitudes of appropriate EPR gz transitions to the Nernst equation for one-electron couple (for WT, H212K, and H198K) or for two one-electron couples (in case of H212K/H198K mutant).

Flash-induced Electron Transfer Measurements

Measurements of flash-induced turnover kinetics of cytochrome bc1 were performed on a home-built double wavelength time-resolved spectrophotometer as described in previous work (24). Chromatophores for measurements were suspended in 50 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 100 mm KCl, 3.5 μm valinomycin, and redox mediators: 7 μm 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, 1 μm phenazine methosulfate, 1 μm phenazine ethosulfate, 5.5 μm 1,2-naphthoquinone, and 5.5 μm 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (valinomycin and redox mediators were added immediately before the measurement). Dithionite and ferricyanide were used to adjust ambient redox potential. Inhibitors antimycin A and myxothiazol were used at final concentration of 7 μm. Transient hemes b reduction kinetics were followed at 560–570 nm (for WT and H198K) or 557–570 nm (for H212K and H212K/H198K). Transient hemes c oxidation and rereduction kinetics were followed at 550–540 nm. Single flash activation measurements were initiated by a short saturating flash (10 μs) from a xenon lamp, and multiple flash activation measurements were initiated by a series of short (10 μs) saturating flashes every 20 ms. In order to measure kinetics in the presence of the membrane potential, valinomycin was omitted. Rates of flash-induced heme b reduction were determined by fitting transient kinetics data to a single exponential equation.

Steady-state Kinetics Measurements

Steady-state enzymatic activities of cytochrome bc1 complexes in chromatophores were determined spectroscopically by the decylubiquinol-dependent reduction of bovine heart cytochrome c (Sigma-Aldrich) as described before (23). Conditions used in assays were as follows: 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 100 mm NaCl, 20 μm decylubiquinol, 20 μm oxidized cytochrome c. Errors were calculated as standard deviation of the mean of nine measurements. Chromatophores were treated with KCN (final concentration in sample was 0.5 mm) before experiments. Decylubiquinol was obtained as described (30).

Results

His-Lys Ligation for Hemes b in a Low Spin State Is Possible in Transmembrane Cytochrome b

Changes in the coordination pattern of heme iron are expected to exert a large influence on the redox properties of hemes (1). Thus, to impose large shifts in Em values of hemes b in cytochrome b, we created three variants in which one of the His ligands to heme iron was replaced by Lys (Lys mutants): single mutants H212K (for heme bH) and H198K (for heme bL) and the double mutant H212K/H198K combining both single mutations (Fig. 2a).

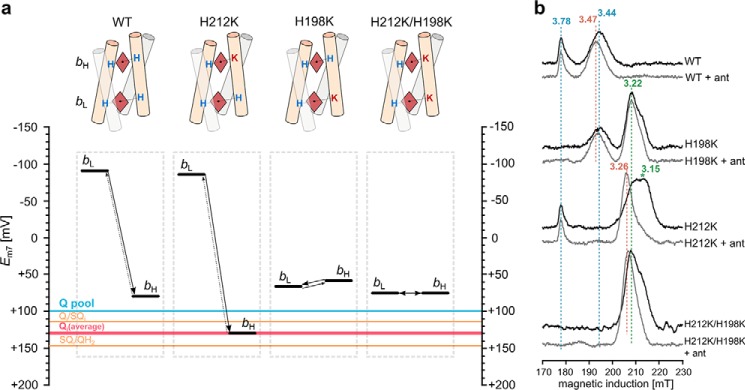

FIGURE 2.

His-Lys coordinated hemes b contain low spin heme iron and have markedly increased Em. a, schematic representation of four-helix bundles (tubes) binding two hemes b (brown diamonds) and introduced changes in the ligation pattern; H and K denote His and Lys ligands of heme iron, respectively. The respective Em diagrams are shown below the schemes. Black bars refer to Em7 of hemes, the blue line indicates Em7 of Q pool, orange lines indicate calculated Em7s of Qi/SQi and SQi/Qi couples (upper and lower line, respectively), and the red line indicates the resulting average Em7 of Q at the Qi catalytic site. b, EPR spectra of hemes b in isolated complexes in the absence of inhibitors and presence of antimycin (black and gray, respectively). The numbers above the spectra and dotted lines denote values and positions of gz transitions.

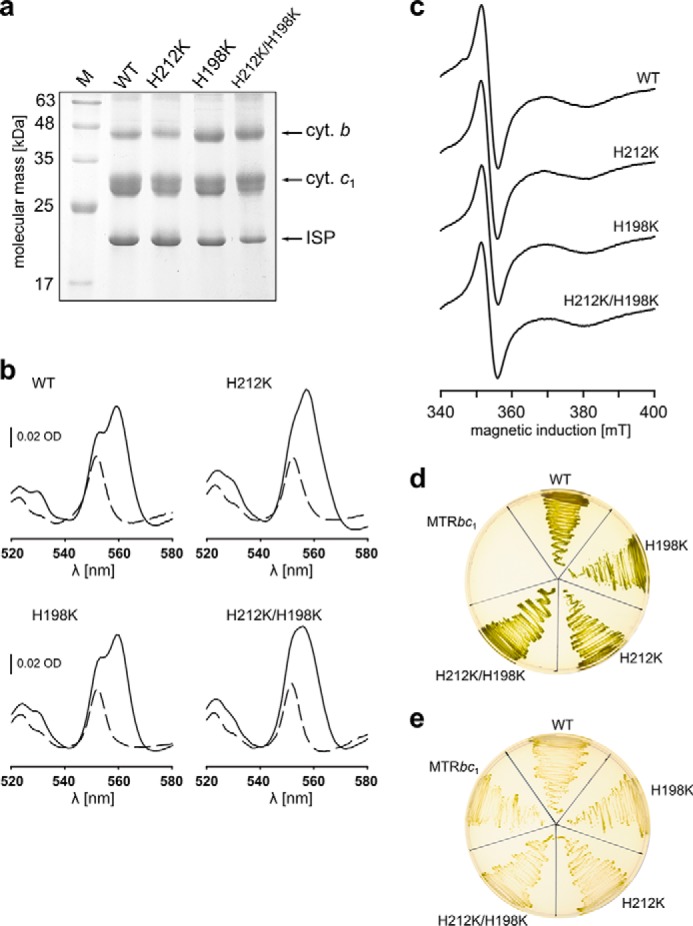

The mutated complexes contained all three catalytic subunits, as indicated by the SDS electrophoretic profiles (Fig. 3a). Optical (UV-visible), and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) showed that the mutants contained all redox active cofactors: heme c1, hemes b (bL and bH) and 2Fe-2S cluster (Figs. 2b and 3, b and c). Although the spectral and redox properties of 2Fe-2S and heme c1 remained unchanged in the mutants, the properties of hemes b were modified. We emphasize the results of EPR analysis (Fig. 2b), which in this case is most informative because, unlike UV-visible spectroscopy, it allows for a complete spectral separation of g transitions originating from each of the hemes b: in native enzyme g = 3.78 and 3.44, corresponding to gz transition of heme bL and heme bH, respectively (31).

FIGURE 3.

SDS-PAGE profiles, spectral analyses, and growth capability of Lys mutants of cytochrome bc1. a, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE profiles of complexes isolated from solubilized membranes. b, optical absorption spectra of isolated complexes: dashed lines, ascorbate-reduced samples; solid lines, dithionite-reduced samples. c, X-band CW-EPR spectra of reduced 2Fe-2S clusters present in samples of isolated complexes. Spectra were recorded at 20 K, 1.7 mT modulation amplitude, and 2.015 milliwatts of microwave power. d, photosynthetic growth under anaerobic conditions at pH 7. MTRbc1 (R. capsulatus strain lacking cytochrome bc1 operon) was used as negative control. e, heterotrophic growth in aerobic dark conditions (cytochrome bc1-independent) at pH 7 was used as positive control.

The mutationally imposed changes in ligation pattern resulted in the disappearance of the gz transition of the targeted heme at the position characteristic for a native enzyme with concomitant appearance of new transitions at g = 3.22 and 3.15 (Fig. 2b, black). More specifically, these new transitions replaced g = 3.78 in H198K, g = 3.44 in H212K, and both g = 3.78 and 3.44 in the double mutant H212K/H198K. In general, these shifts reflect a lowering of the symmetry and changes from a highly axial to a more rhombic low spin heme (32). The new transitions g = 3.22 and 3.15 are assigned to gz transitions of low spin hemes b coordinated by His-Lys. Support for this assignment comes from the differential effect of antimycin, an inhibitor that binds to the Qi site in the proximity of heme bH, and is known to affect the EPR spectrum of heme bH (33). Antimycin clearly affects the g = 3.22 and 3.15 of heme bH in H212K and H212K/H198K, whereas in H198K it has a weak or no effect (Fig. 2b, gray). In H212K/H198K, for which both hemes bL and bH contribute to 3.22 and 3.15 transitions, the effect of antimycin is intermediary between the largest and smallest effect seen in H212K and H198K, respectively.

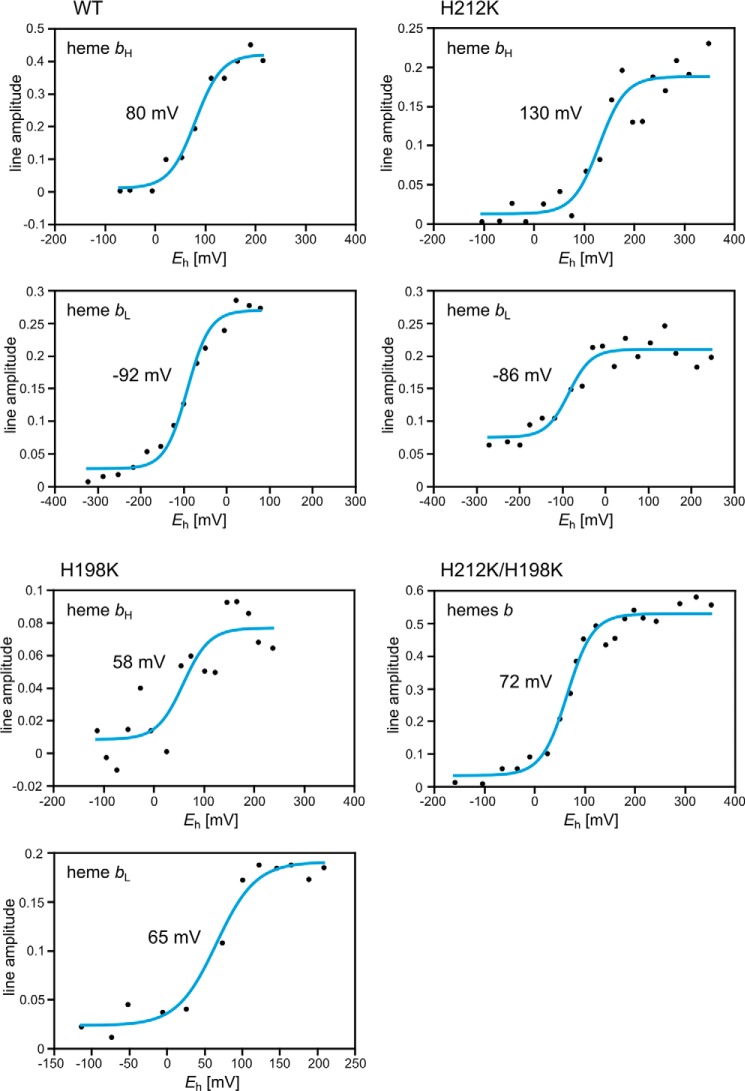

His-Lys Coordinated Hemes b Have Markedly Elevated Em, Effectively Modulating ΔEm_b

Dark equilibrium redox titrations revealed that changing the ligation pattern from bis-His to His-Lys in hemes b leads to a significant increase in their Em values. This increase reaches 50 mV for heme bH in H212K and almost 160 mV for heme bL in H198K (Fig. 4 and Table 1). At the same time, there was no significant change of Em (only ∼10 mV increase was observed in Em for heme bL in H212K or 20 mV decrease of Em for heme bH in H198K) in the heme that was not subject to modification in these mutants. A large increase in the Em of just one heme (bL or bH) effectively modulated ΔEm_b in those mutants (Fig. 2a). In H212K ΔEm_b was increased, and Em of heme bH rose above the Em of quinone pool in the membrane (34, 35). In H198K ΔEm_b was decreased to the point that both hemes became almost isopotential. In H212K/H198K, both His-Lys ligated hemes showed Em of ∼72 mV. This means that only heme bL elevated its Em. Consequently, the ΔEm_b in this mutant is similar to that of H198K.

FIGURE 4.

Midpoint potentials of hemes b determined via EPR-monitored redox titrations. Each blue line represents the Nernst titration curve. The respective Em values are given in the middle of each plot. Titrations were performed on isolated chromatophores at pH 7.0. Amplitudes of heme bL and heme bH were monitored at respective g values: 3.78 and 3.44 in WT, 3.22 and 3.44 in H198K, 3.78 and 3.2 in H212K, and 3.2 in H212K/H198K.

Mutants with Large Changes in ΔEm_b Are Functional in Vitro and in Vivo

Remarkably, all mutants showed the capability to grow under cytochrome bc1-dependent photoheterotrophic conditions (i.e. exhibited the Ps+ phenotype), which indicated that mutated cytochromes bc1 are functional in vivo (Table 1 and Fig. 3, d and e). The functional competence of these mutants was confirmed by light-induced electron transfer measurements that allow monitoring of individual reactions associated with the catalytic cycle. In brief, these reactions include oxidation of quinol at the Qo site, which delivers one electron to one cofactor chain (the c chain) consisting of a 2Fe-2S cluster, heme c1 and heme c2. The other electron is used to reduce heme bL in a separate chain (the b chain), followed by cross-membrane electron transfer to heme bH, which then reduces the occupant of the Qi site.

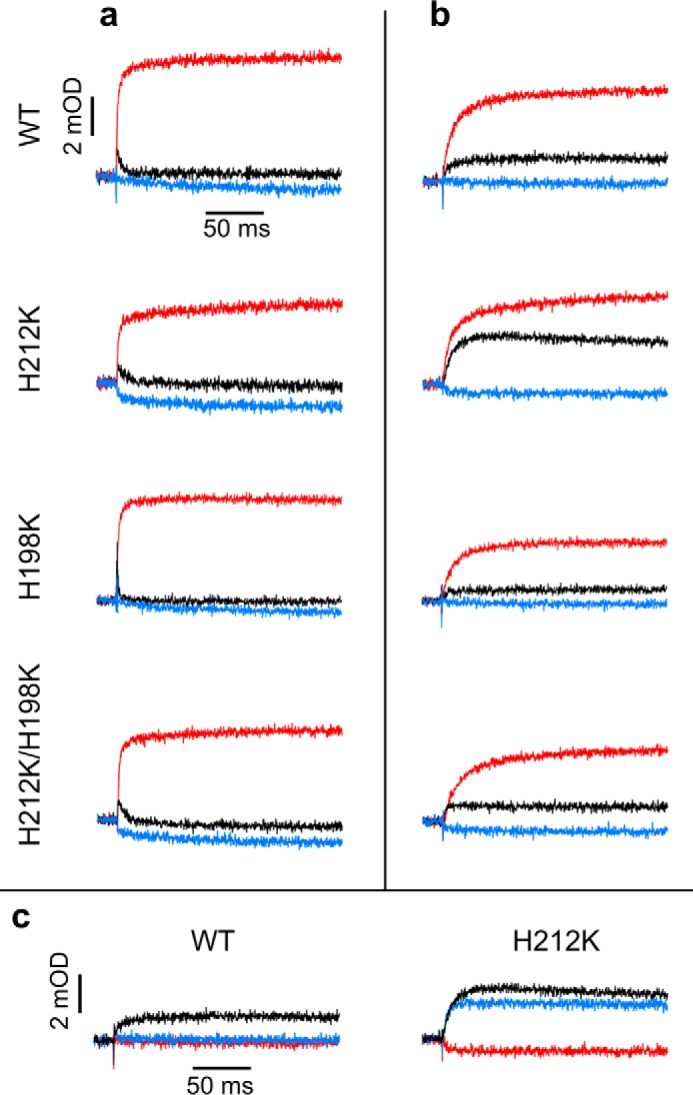

The kinetic transients shown in Fig. 5 monitored changes in the oxidation state of heme bH associated with electron transfer through the b chain. When the quinone (Q) pool is poised half-reduced before light activation (ambient potential of 100 mV at pH 7) (Fig. 5a), cytochrome bc1 in native chromatophores and in the absence of any inhibitors displays a fast reduction of heme bH followed by its fast reoxidation (WT, black trace). The reduction phase is mediated by an electron from the Qo site, whereas the reoxidation phase results from electron transfer to the occupant of the Qi site. In the presence of antimycin, the reoxidation phase is blocked, and heme bH remains reduced within the time domain monitored in the experiment (WT, red trace). The rate of this reduction (measured at pH 7), as well as the rates measured at two other pH values (pH 6 and 9, which test conditions of different driving force provided by substrates) are listed in Table 1. All phases of the electron transfer described above and involving heme bH (in the absence of any inhibitors and in the presence of antimycin) are observed in all Lys mutants, and the measured rates of heme bH reduction at pH 6, 7, or 9 are only slightly lower than the corresponding rates in wild type (Fig. 5a and Table 1). This reveals a full competence of catalytic reactions of Qo and Qi sites in the mutants. We note the smaller amplitude of heme bH reduction in the presence of antimycin in H212K mutant. This is an effect of a partial prereduction of this heme before activation, which is a consequence of an elevated Em exceeding the Em of the Q pool.

FIGURE 5.

Single flash-activated transients reveal fast heme b reduction and changes in equilibria of partial reactions in Lys mutants. a, transients in the absence of inhibitor (black) after addition of antimycin (red) and subsequent addition of myxothiazol (blue) recorded at pH 7 and ambient potential of 100 mV (Q pool half-reduced). b, same as in a, except that ambient potential was 200 mV (Q pool oxidized). c, same as in b, except that the order of addition of inhibitors was inverted: antimycin (red) was subsequent to myxothiazol (blue). Transient hemes b reduction kinetics for WT and H198K were followed at 560–570 nm and for H212K and H212K/H198K at 557–570 nm.

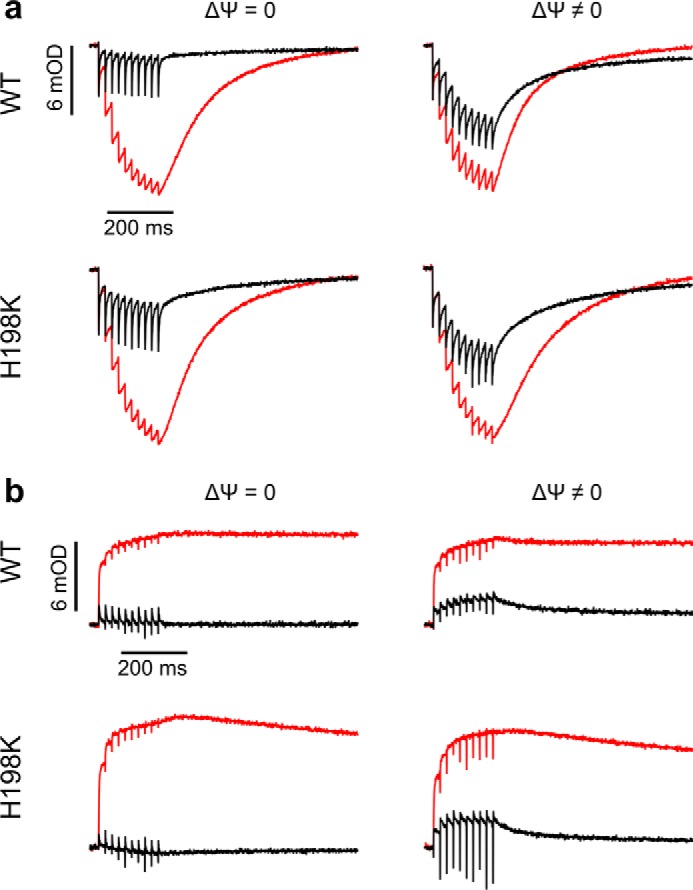

Kinetic competence of the mutants was also evident in the response of cytochrome bc1 to multiple flash activation in both the absence and presence of membrane potential. In the absence of inhibitors, hemes c in native enzyme and H198K undergo several cycles of fast oxidation and rereduction (Fig. 6a, black), and hemes b undergo several cycles of fast reduction and reoxidation (Fig. 6b, black). As expected, antimycin impedes the rereduction phase of hemes c (Fig. 6a, red) and blocks the reoxidation phase of hemes b (Fig. 6b, red). The membrane potential diminishes the effectiveness of the rereduction of hemes c and reoxidation of hemes b, leading to partial accumulation of oxidized hemes c and reduced hemes b, but the magnitude of this effect in native enzyme and H198K is similar. In multiple flash experiments, H212K behaved similarly to H198K.

FIGURE 6.

Multiple flash-activated competence of enzyme with isopotential hemes b in the absence and presence of electric membrane potential. a, transients for hemes c oxidation and rereduction in WT and H198K activated by 10 flashes separated by 20 ms in the absence of inhibitors (black) and in the presence of antimycin (red), in the absence (ΔΨ = 0) or presence (ΔΨ ≠ 0) of the membrane potential, recorded at pH 7 and ambient potential of 100 mV. b, transients for hemes b recorded as in a.

Enzymatic competence of the Lys mutants is evident in the measured steady-state turnover rates, which remain in good correlation with the results of light-induced electron transfer measurements. As listed in Table 1, the turnover rates in H212K or H198K single mutants and in H212K/H198K double mutant decrease by 20 and 40%, respectively, compared with WT. Clearly, all Lys mutants retain significant enzymatic activity.

Changes in ΔEm_b Affect Equilibria of Partial Reactions

Kinetic traces measured when the Q pool is fully oxidized before activation (ambient potential of 200 mV at pH 7) are compared in Fig. 5b. Under these conditions, the amount of quinol molecules after activation is limited, and consequently, approximately only one quinol is oxidized in every Qo site. It follows that a difference between the level of reduction of heme bH in the absence and presence of antimycin reports equilibration of electron between heme bH3+/bH2+ and quinone/semiquinone (Q/SQ) couples at the Qi site. In native enzyme and H198K mutant, this difference is large, indicating that the electron resides mostly on semiquinone at the Qi site (∼80%). However, in H212K mutant, the amplitude of reduced heme bH in the absence of inhibitors is significantly larger than in wild type. This indicates that equilibrium between heme bH3+/bH2+ and Q/SQ is shifted so that the electron resides mostly on heme bH (at the expense of semiquinone). This shift is a consequence of an elevated Em of heme bH in H212K, which exceeds the Em of Q/SQ at pH 7 (Fig. 2a).

Another way to monitor electron equilibration between heme bH and the occupant of the Qi site benefits from the occurrence of reverse reaction in the Qi site (Fig. 5c). When the Q pool is fully oxidized before light activation, and the Qo site is blocked by an inhibitor (myxothiazol), light-induced reduction of heme bH reports electron transfer from quinol that entered the Qi site to heme bH. However, in a native enzyme, this reaction cannot be observed at pH 7 (Fig. 5c, blue), which seems consistent with the fact that Em of heme bH is lower than Em of the Q pool. On the other hand, at this pH, the reverse electron transfer from Qi site quinol to heme bH is prominent in H212K (Fig. 5c, blue). Furthermore, the amplitude of heme bH reduction in this reaction (i.e. in the presence of myxothiazol) is almost as large as the amplitude of heme bH reduction in the absence of any inhibitor.

Equilibration of electrons between heme bH and the occupant of the Qi site in H212K mutant under the conditions described in Fig. 5 (b and c) allowed us to estimate the Em values for the SQ/QH2 and Q/SQ redox couples at the Qi site at pH 7. The extent of forward reaction (electron transfer from heme bH to Q) monitored in Fig. 5b will reflect the difference between the Em of heme bH3+/bH2+ and the Em of Q/SQ couples, whereas the extent of the reverse reaction (electron transfer from quinol to heme bH) monitored in Fig. 5c will reflect the difference between the Em of heme bH3+/bH2+ and the Em of SQ/QH2 couples. Based on these assumptions, and considering Em7 = 130 mV for heme bH in an H212K mutant, we estimate values of Em7 for the Q/SQ couple to be ∼114 mV, and Em7 for the SQ/QH2 couple to be 147 mV. The average redox midpoint potential for Q/QH2 (Em7 for Q/QH2) is then 130 mV, which makes it isopotential with the bH3+/bH2+ couple in an H212K mutant and ∼30 mV higher than the Em of Q in the Q pool reported in the literature. The split in quinone redox couples defines the stability constant for SQ (35, 36); thus, our estimates of Em7 for Q/SQ and Em7 for SQ/QH2 indicate the stability constant (log(Ks) = [Em(Q/SQ) − Em(SQ/QH2)]/60) for SQi at the level of 3 × 10−1.

Discussion

We have examined the effect of large changes in ΔG on electron transfer between hemes b in cytochrome bc1. These changes were implemented by significant increases in the Em values of the hemes, which came as a result of mutating the native bis-His coordination of the heme iron into the His-Lys coordination. Our results indicate that the natural difference in Em values of the two hemes b (ΔEm_b) of 170 mV can be increased to 210 mV (in H212K) or diminished to almost 0 (in H198K and double mutant H212K/H198K), and the complex still remains functional in vivo, retaining the catalytically relevant electron transfer from the Qo to Qi sites measured in vitro under the absence or presence of membrane potential. The electron flow through cofactor chains of cytochrome bc1 in all those mutants proceeded from the primary electron donor (QH2 in the Qo site) to the final electron acceptor (Q or SQ in the Qi site) at physiologically and mechanistically competent rates, although changes in ΔEm_b affected equilibrium levels of partial reactions in the coupled electron transfer chains. Clearly, these changes did not introduce any significant barrier to electron transfer from donor to final acceptor. It thus appears that cytochrome bc1 can accommodate large changes in ΔEm_b without hampering catalysis, as long as these changes do not impose overly endergonic steps on the route of electron transfer from substrate to product. The previously reported moderate decrease in Em for heme bH in yeast cytochrome bc1 falls into this category of changes, i.e. ones not imposing overly endergonic steps, and thus, consistent with our observations, did not affect significantly the measured turnover rate of the enzyme (20).

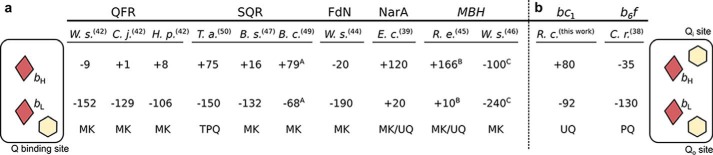

Considering the direction of electron flow and the direction of the gradient of Em in relation to the vector of the electric membrane potential, four configurations are possible (Fig. 1). In cytochrome bc1 (11, 12), cytochrome b6f (37, 38), nitrate reductase A (39, 40), and quinol-fumarate reductase (41, 42), the high potential heme b is located at the negative side of the membrane (Fig. 1a), which at first would seem to be in line with the concept of the obligatory difference in Em to overcome membrane potential. However, in formate dehydrogenase N (40, 43, 44) and probably in membrane-bound [Ni-Fe] hydrogenase (45, 46), the low potential heme is located at the negative side of the membrane, and the electron is transferred against both the electric membrane and the redox potential of hemes b (Fig. 1b), which remains at odds with the concept presented above. The third possibility found in succinate-quinone reductase (47–50), NADPH oxidase (51), or cytochrome b561 family (52–54) is simply an inversion of the case in Fig. 1a with electron transfer from high to low potential facilitated by the presence of electric membrane potential (Fig. 1c). The fourth possibility (Fig. 1d) perhaps concerns proton motive force-driven electron transfer in thiosulfate reductase, if heme bL in this enzyme is located close to the menaquinone binding site, as in formate dehydrogenase N (which seems likely, based on sequence similarities between the cytochrome b subunits of these complexes) (55).

The occurrence of all these configurations suggests that there is no a universal rule for the arrangement of Em values of hemes b among various transmembrane cytochromes b. This, however, becomes understandable in light of our observation that large ΔEm_b and fine tuning of Em values of hemes b of cytochrome bc1 are not required for efficient cross-membrane electron transfer. Another example of tolerance for changes in ΔEm_b for cross-membrane electron transfer concerns Bacillus subtilis succinate-quinone reductase. In this case, the mutant with the His-Met ligated heme bL having the Em increased by at least 100 mV is expected to diminish the barrier for the uphill step of electron transfer from heme bH to heme bL (Fig. 1c) but, at the same time, to introduce a barrier for electron transfer from heme bL to menaquinone. However, such modification, despite lowered enzymatic activity, did not eliminate the function of the enzyme in vivo. Furthermore, its activity to reduce ubiquinone was not significantly affected (48).

Extrapolating all these observations to other cytochromes b, it can be proposed that, in all those proteins, hemes b simply act as electronic connectors for the catalytic sites with no fine tuning in ΔEm_b required for efficient electron transfer. It follows that the existence of ΔEm_b in transmembrane embedded hemes b is not an element in the control of electron flow across the membrane. Rather, it may be a consequence of a higher probability of coexistence of two cofactors having different Em in comparison to the case when the two cofactors have similar Em. Intriguingly, we found one resemblance for enzymes with one quinone binding site: from two hemes b of different potentials, the one with the lower potential is adjacent to the quinone binding site (Fig. 7) (38, 39, 42, 44–47, 49, 50). Further studies are required to verify whether this has any functional relevance or is just a consequence of structural constraints. Nevertheless, this resemblance may be useful in predicting the location of low and high potential heme b in quinol-binding cytochromes, for which such assignments are yet to be made.

FIGURE 7.

Localization of low and high potential hemes b with respect to the quinone binding site in cytochrome b subunits of enzymes involved in cross-membrane electron transfer. a, in cytochromes b with one Q binding site, low potential heme (bL) is adjacent to the Q binding site, whereas high potential heme (bH) faces the opposite side of the membrane. b, in cytochromes bc, the cytochrome b subunit contains two Q binding sites and heme bL is adjacent to one site (Qo), whereas heme bH is adjacent to the other (Qi). Brown diamonds, hemes b; yellow hexagons, Q binding sites. Numbers indicate Em values (in mV) for pH 7. Superscripts A, B, and C refer to Em values for pH 7.6, 7.2, and 7.5, respectively. Types of natively used quinones are given below the Em values. Localization of hemes in membrane-bound [Ni-Fe] hydrogenase (MBH) is presumable; thus, its name is given in italic. Protein names abbreviations as in Fig. 1. Other abbreviations as follow: B. c., Bacillus cereus; B. s., Bacillus subtilis; C. j., Campylobacter jejuni; C. r., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii; E. c., Escherichia coli; H. p., Helicobacter pylori; R. e., Ralstonia eutropha; R. c., Rhodobacter capsulatus; T. a., Thermoplasma acidophilum; W. s., Wolinella succinogenes; MK, menaquinone; TPQ, thermoplasmaquinone; PQ, plastoquinone; UQ, ubiquinone.

The demonstrated robustness of cytochrome b to changes in ligation pattern and associated changes in ΔEm_b raises an interesting question as to whether variation in the heme ligation patterns exists in natural membrane proteins of similar design and/or function. Such variation is evident in the group of cytochromes c for which bis-His (4, 56, 57), His-Met (4, 56, 57), His-Lys (58), His-Cys (59–61), or even His-Tyr (62, 63) patterns ligating heme iron are observed. However, in most known cytochromes c, the heme binding domains are water-soluble or solvent-exposed (so far, the heme cx from cytochrome b6 is the only known exception (5, 64, 65)), whereas in cytochromes b these domains can be located either in membrane or in aqueous phase (5). It may seem that the location of the heme binding motifs outside the membrane environment is one of the factors increasing structural flexibility to accommodate diverse heme ligation. Indeed, all rare cases of His-Met (66, 67), Lys-Met (68), or bis-Met (69, 70) ligations in cytochromes b are relevant only to water-soluble domains. In fact, to our knowledge, no cases have been reported so far of Met or Lys serving naturally as axial ligands for hemes bound within the integral membrane proteins.

However, our Lys mutants prove that His-Lys ligation for hemes b can occur within the transmembrane helix bundle of cytochrome b, yielding functional hemes that contain a low spin form of iron ion. Notably, the H212K mutant was originally isolated as a reversion for H212N, the so-called heme bH knock-out, with impaired electron transfer at the level of the heme bH/Qi site. Likewise, the His-Met heme b mutant of B. subtilis succinate-quinone reductase was isolated as a reversion of nonfunctional Leu mutant (48). This all indicates that an assembly of functionally active low spin heme b present within the transmembrane segment of the protein and coordinated by His and Lys or Met is feasible from a protein engineering perspective. If this is the case, one should expect that there are natural cases of His-Lys and His-Met ligation patterns for membranous heme proteins (71) that still await identification, especially because the range of scrutinized heme proteins is currently continuously widening.

Author Contributions

S. P. performed most of the biochemical and spectroscopic experiments and analyzed data; P. K. performed light-induced electron transfer measurements; E. C. constructed mutants and contributed preliminary results; A. B. performed enzymatic activity assays; and S. P., M. S., and A. O. designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and cowrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wolfgang Nitschke for useful discussions and Dr. Robert Ekiert for technical assistance.

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust International Senior Research Fellowship (to A. O.). The Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology of Jagiellonian University is a partner of the Leading National Research Center (KNOW) supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- Qo

- quinol oxidation site

- Qi

- quinone reduction site

- EPR

- electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- Q

- quinone

- QH2

- quinol

- SQ

- semiquinone.

References

- 1. Wallace C. J., and Clark-Lewis I. (1992) Functional role of heme ligation in cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3852–3861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Battistuzzi G., Borsari M., Cowan J. A., Ranieri A., and Sola M. (2002) Control of cytochrome c redox potential: axial ligation and protein environment effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 5315–5324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mao J., Hauser K., and Gunner M. R. (2003) How cytochromes with different folds control heme redox potentials. Biochemistry 42, 9829–9840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fufezan C., Zhang J., and Gunner M. R. (2008) Ligand preference and orientation in b- and c-type heme-binding proteins. Proteins 73, 690–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koch H.-G., and Schneider D. (2007) Folding, assembly, and stability of transmembrane cytochromes. Curr. Chem. Biol. 1, 59–74 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volkmer T., Becker C., Prodöhl A., Finger C., and Schneider D. (2006) Assembly of a transmembrane b-type cytochrome is mainly driven by transmembrane helix interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1815–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berry E. A., and Walker F. A. (2008) Bis-histidine-coordinated hemes in four-helix bundles: how the geometry of the bundle controls the axial imidazole plane orientations in transmembrane cytochromes of mitochondrial complexes II and III and related proteins. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 13, 481–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertson D. E., Farid R. S., Moser C. C., Urbauer J. L., Mulholland S. E., Pidikiti R., Lear J. D., Wand A. J., DeGrado W. F., and Dutton P. L. (1994) Design and synthesis of multi-haem proteins. Nature 368, 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koder R. L., Anderson J. L., Solomon L. A., Reddy K. S., Moser C. C., and Dutton P. L. (2009) Design and engineering of an O2 transport protein. Nature 458, 305–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farid T. A., Kodali G., Solomon L. A., Lichtenstein B. R., Sheehan M. M., Fry B. A., Bialas C., Ennist N. M., Siedlecki J. A., Zhao Z., Stetz M. A., Valentine K. G., Anderson J. L., Wand A. J., Discher B. M., Moser C. C., and Dutton P. L. (2013) Elementary tetrahelical protein design for diverse oxidoreductase functions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 826–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xia D., Esser L., Tang W.-K., Zhou F., Zhou Y., Yu L., and Yu C.-A. (2013) Structural analysis of cytochrome bc1 complexes: implications to the mechanism of function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1278–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarewicz M., and Osyczka A. (2015) Electronic connection between the quinone and cytochrome c redox pools and its role in regulation of mitochondrial electron transport and redox signaling. Physiol. Rev. 95, 219–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Swierczek M., Cieluch E., Sarewicz M., Borek A., Moser C. C., Dutton P. L., and Osyczka A. (2010) An electronic bus bar lies in the core of cytochrome bc1. Science 329, 451–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lanciano P., Lee D.-W., Yang H., Darrouzet E., and Daldal F. (2011) Intermonomer electron transfer between the low-potential b hemes of cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry 50, 1651–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lanciano P., Khalfaoui-Hassani B., Selamoglu N., and Daldal F. (2013) Intermonomer electron transfer between the b hemes of heterodimeric cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry 52, 7196–7206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ekiert R., Czapla M., Sarewicz M., and Osyczka A. (2014) Hybrid fusions show that inter-monomer electron transfer robustly supports cytochrome bc1 function in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 451, 270–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shinkarev V. P., Crofts A. R., and Wraight C. A. (2001) The electric field generated by photosynthetic reaction center induces rapid reversed electron transfer in the bc1 complex. Biochemistry 40, 12584–12590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicholls D. G., and Ferguson S. J. (2013) Bioenergetics, 4th Ed., Academic Press, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brasseur G., Sariba A. S., and Daldal F. (1996) A compilation of mutations located in the cytochrome b subunit of the bacterial and mitochondrial bc1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275, 61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rotsaert F. A., Covian R., and Trumpower B. L. (2008) Mutations in cytochrome b that affect kinetics of the electron transfer reactions at center N in the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yun C. H., Crofts A. R., and Gennis R. B. (1991) Assignment of the histidine axial ligands to the cytochrome bH and cytochrome bL components of the bc1 complex from Rhodobacter sphaeroides by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 30, 6747–6754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Osyczka A., Moser C. C., Daldal F., and Dutton P. L. (2004) Reversible redox energy coupling in electron transfer chains. Nature 427, 607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Atta-Asafo-Adjei E., and Daldal F. (1991) Size of the amino acid side chain at position 158 of cytochrome b is critical for an active cytochrome bc1 complex and for photosynthetic growth of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 492–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cieluch E., Pietryga K., Sarewicz M., and Osyczka A. (2010) Visualizing changes in electron distribution in coupled chains of cytochrome bc1 by modifying barrier for electron transfer between the FeS cluster and heme c1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 296–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Czapla M., Borek A., Sarewicz M., and Osyczka A. (2012) Fusing two cytochromes b of Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome bc1 using various linkers defines a set of protein templates for asymmetric mutagenesis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 25, 15–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Valkova-Valchanova M. B., Saribas A. S., Gibney B. R., Dutton P. L., and Daldal F. (1998) Isolation and characterization of a two-subunit cytochrome b-c1 subcomplex from Rhodobacter capsulatus and reconstitution of its ubihydroquinone oxidation (Qo) site with purified Fe-S protein subunit. Biochemistry 37, 16242–16251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Czapla M., Borek A., Sarewicz M., and Osyczka A. (2012) Enzymatic activities of isolated cytochrome bc1-like complexes containing fused cytochrome b subunits with asymmetrically inactivated segments of electron transfer chains. Biochemistry 51, 829–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Osyczka A., Dutton P. L., Moser C. C., Darrouzet E., and Daldal F. (2001) Controlling the functionality of cytochrome c1 redox potentials in the Rhodobacter capsulatus bc1 complex through disulfide anchoring of a loop and a b-branched amino acid near the heme-ligating methionine. Biochemistry 40, 14547–14556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dutton P. L. (1978) Redox potentiometry: determination of midpoint potentials of oxidation-reduction components of biological electron transfer systems. Methods Enzymol. 54, 411–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sarewicz M., Dutka M., Pintscher S., and Osyczka A. (2013) Triplet state of the semiquinone-Rieske cluster as an intermediate of electronic bifurcation catalyzed by cytochrome bc1. Biochemistry 52, 6388–6395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finnegan M. G., Knaff D. B., Qin H., Gray K. A., Daldal F., Yu L., Yu C. A., Kleis-San Francisco S., and Johnson M. K. (1996) Axial heme ligation in the cytochrome bc1 complexes of mitochondrial and photosynthetic membranes. A near-infrared magnetic circular dichroism and electron paramagnetic resonance study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1274, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zoppellaro G., Bren K. L., Ensign A. A., Harbitz E., Kaur R., Hersleth H.-P., Ryde U., Hederstedt L., and Andersson K. K. (2009) Studies of ferric heme proteins with highly anisotropic/highly axial low spin (S = 1/2) electron paramagnetic resonance signals with bis-histidine and histidine-methionine axial iron coordination. Biopolymers 91, 1064–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robertson D. E., Ding H., Chelminski P. R., Slaughter C., Hsu J., Moomaw C., Tokito M., Daldal F., and Dutton P. L. (1993) Hydroubiquinone-cytochrome c2 oxidoreductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus: definition of a minimal, functional isolated preparation. Biochemistry 32, 1310–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takamiya K. I., and Dutton P. L. (1979) Ubiquinone in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides: some thermodynamic properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 546, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang H., Chobot S. E., Osyczka A., Wraight C. A., Dutton P. L., and Moser C. C. (2008) Quinone and non-quinone redox couples in complex III. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Osyczka A., Moser C. C., and Dutton P. L. (2005) Fixing the Q cycle. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 176–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saif Hasan S., Yamashita E., and Cramer W. A. (2013) Transmembrane signaling and assembly of the cytochrome b6f-lipidic charge transfer complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1295–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alric J., Pierre Y., Picot D., Lavergne J., and Rappaport F. (2005) Spectral and redox characterization of the heme ci of the cytochrome b6f complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15860–15865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rothery R. A., Blasco F., Magalon A., and Weiner J. H. (2001) The diheme cytochrome b subunit (Narl) of Escherichia coli nitrate reductase A (NarGHI): structure, function, and interaction with quinols. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3, 273–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jormakka M., Byrne B., and Iwata S. (2003) Protonmotive force generation by a redox loop mechanism. FEBS Lett. 545, 25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haas A. H., and Lancaster C. R. (2004) Calculated coupling of transmembrane electron and proton transfer in dihemic quinol:fumarate reductase. Biophys. J. 87, 4298–4315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mileni M., MacMillan F., Tziatzios C., Zwicker K., Haas A. H., Mäntele W., Simon J., and Lancaster C. R. (2006) Heterologous production in Wolinella succinogenes and characterization of the quinol:fumarate reductase enzymes from Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni. Biochem. J. 395, 191–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jormakka M., Törnroth S., Byrne B., and Iwata S. (2002) Molecular basis of proton motive force generation: structure of formate dehydrogenase-N. Science 295, 1863–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kröger A., Winkler E., Innerhofer A., Hackenberg H., and Schägger H. (1979) The formate dehydrogenase involved in electron transport from formate to fumarate in Vibrio succinogenes. Eur. J. Biochem. 94, 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Frielingsdorf S., Schubert T., Pohlmann A., Lenz O., and Friedrich B. (2011) A trimeric supercomplex of the oxygen-tolerant membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase from Ralstonia eutropha H16. Biochemistry 50, 10836–10843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gross R., Pisa R., Sänger M., Lancaster C. R., and Simon J. (2004) Characterization of the menaquinone reduction site in the diheme cytochrome b membrane anchor of Wolinella succinogenes NiFe-hydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hägerhäll C., Fridén H., Aasa R., and Hederstedt L. (1995) Transmembrane topology and axial ligands to hemes in the cytochrome b subunit of Bacillus subtilis succinate:menaquinone reductase. Biochemistry 34, 11080–11089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Matsson M., Tolstoy D., Aasa R., and Hederstedt L. (2000) The distal heme center in Bacillus subtilis succinate:quinone reductase is crucial for electron transfer to menaquinone. Biochemistry 39, 8617–8624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. García L. M., Contreras-Zentella M. L., Jaramillo R., Benito-Mercadé M. C., Mendoza-Hernández G., del Arenal I. P., Membrillo-Hernández J., and Escamilla J. E. (2008) The succinate:menaquinone reductase of Bacillus cereus: characterization of the membrane-bound and purified enzyme. Can. J. Microbiol. 54, 456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gärtner P. (1991) Characterization of a quinole-oxidase activity in crude extracts of Thermoplasma acidophilum and isolation of an 18-kDa cytochrome. Eur. J. Biochem. 200, 215–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu L., Quinn M. T., Cross A. R., and Dinauer M. C. (1998) Gp91phox is the heme binding subunit of the superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7993–7998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Desmet F., Bérczi A., Zimányi L., Asard H., and Van Doorslaer S. (2011) Axial ligation of the high-potential heme center in an Arabidopsis cytochrome b561. FEBS Lett. 585, 545–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kamensky Y., Liu W., Tsai A.-L., Kulmacz R. J., and Palmer G. (2007) Axial ligation and stoichiometry of heme centers in adrenal cytochrome b561. Biochemistry 46, 8647–8658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lu P., Ma D., Yan C., Gong X., Du M., and Shi Y. (2014) Structure and mechanism of a eukaryotic transmembrane ascorbate-dependent oxidoreductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 1813–1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stoffels L., Krehenbrink M., Berks B. C., and Unden G. (2012) Thiosulfate reduction in Salmonella enterica is driven by the proton motive force. J. Bacteriol. 194, 475–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bewley K. D., Ellis K. E., Firer-Sherwood M. A., and Elliott S. J. (2013) Multi-heme proteins: nature's electronic multi-purpose tool. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 938–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bertini I., Cavallaro G., and Rosato A. (2006) Cytochrome c: occurrence and functions. Chem. Rev. 106, 90–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rodrigues M. L., Oliveira T. F., Pereira I. A., and Archer M. (2006) X-ray structure of the membrane-bound cytochrome c quinol dehydrogenase NrfH reveals novel haem coordination. EMBO J. 25, 5951–5960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kappler U., Aguey-Zinsou K.-F., Hanson G. R., Bernhardt P. V., and McEwan A. G. (2004) Cytochrome c551 from Starkeya novella: characterization, spectroscopic properties, and phylogeny of a diheme protein of the SoxAX family. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6252–6260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kilmartin J. R., Maher M. J., Krusong K., Noble C. J., Hanson G. R., Bernhardt P. V., Riley M. J., and Kappler U. (2011) Insights into structure and function of the active site of SoxAX cytochromes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24872–24881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suga M., Lai T. L., Sugiura M., Shen J. R., and Boussac A. (2013) Crystal structure at 1.5Å resolution of the PsbV2 cytochrome from the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus. FEBS Lett. 587, 3267–3272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jensen L. M., Meharenna Y. T., Davidson V. L., Poulos T. L., Hedman B., Wilmot C. M., and Sarangi R. (2012) Geometric and electronic structures of the His–Fe(IV)=O and His–Fe(IV)–Tyr hemes of MauG. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 17, 1241–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jensen L. M., Sanishvili R., Davidson V. L., and Wilmot C. M. (2010) In crystallo posttranslational modification within a MauG/pre-methylamine dehydrogenase complex. Science 327, 1392–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kurisu G., Zhang H., Smith J. L., and Cramer W. A. (2003) Structure of the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis: tuning the cavity. Science 302, 1009–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stroebel D., Choquet Y., Popot J.-L., and Picot D. (2003) An atypical haem in the cytochrome b6f complex. Nature 426, 413–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mathews F. S., Bethge P. H., and Czerwinski E. W. (1979) The structure of cytochrome b562 from Escherichia coli at 2.5 A resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 1699–1706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rotsaert F. A., Hallberg B. M., de Vries S., Moenne-Loccoz P., Divne C., Renganathan V., and Gold M. H. (2003) Biophysical and structural analysis of a novel heme b iron ligation in the flavocytochrome cellobiose dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33224–33231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kloer D. P., Hagel C., Heider J., and Schulz G. E. (2006) Crystal structure of ethylbenzene dehydrogenase from Aromatoleum aromaticum. Structure 14, 1377–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cheesman M. R., Thomson A. J., Greenwood C., Moore G. R., and Kadir F. (1990) Bis-methionine axial ligation of haem in bacterioferritin from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nature 346, 771–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ran Y., Zhu H., Liu M., Fabian M., Olson J. S., Aranda R. 4th, Phillips G. N. Jr., Dooley D. M., and Lei B. (2007) Bis-methionine ligation to heme iron in the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp facilitates rapid hemin transfer to HtsA of the HtsABC transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31380–31388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bérczi A., Desmet F., Van Doorslaer S., and Asard H. (2010) Spectral characterization of the recombinant mouse tumor suppressor 101F6 protein. Eur. Biophys. J. 39, 1129–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]