Abstract

An important strategy for promoting voluntary movements after motor system injury is to harness activity-dependent corticospinal tract (CST) plasticity. We combine forelimb motor cortex (M1) activation with co-activation of its cervical spinal targets in rats to promote CST sprouting and skilled limb movement after pyramidal tract lesion (PTX). We used a two-step experimental design in which we first established the optimal combined stimulation protocol in intact rats and then used the optimal protocol in injured animals to promote CST repair and motor recovery. M1 was activated epidurally using an electrical analog of intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS). The cervical spinal cord was co-activated by trans-spinal direct current stimulation (tsDCS) that was targeted to the cervical enlargement, simulated from finite element method. In intact rats, forelimb motor evoked potentials (MEPs) were strongly facilitated during iTBS and for 10 minutes after cessation of stimulation. Cathodal, not anodal, tsDCS alone facilitated MEPs and also produced a facilitatory aftereffect that peaked at 10 minutes. Combined iTBS and cathodal tsDCS (c-tsDCS) produced further MEP enhancement during stimulation, but without further aftereffect enhancement. Correlations between forelimb M1 local field potentials and forelimb electromyogram (EMG) during locomotion increased after electrical iTBS alone and further increased with combined stimulation (iTBS + c-tsDCS). This optimized combined stimulation was then used to promote function after PTX because it enhanced functional connections between M1 and spinal circuits and greater M1 engagement in muscle contraction than either stimulation alone. Daily application of combined M1 iTBS on the intact side and c-tsDCS after PTX (10 days, 27 minutes/day) significantly restored skilled movements during horizontal ladder walking. Stimulation produced a 5.4-fold increase in spared ipsilateral CST terminations. Combined neuromodulation achieves optimal motor recovery and substantial CST outgrowth with only 27 minutes of daily stimulation compared with 6 hours, as in our prior study, making it a potential therapy for humans with spinal cord injury.

Introduction

Motor systems injury produces weakness and paralysis. Interruption of corticospinal tract (CST) connections between motor cortex (M1) and spinal motor circuits is thought to underlie this impairment. Injury typically does not completely lesion the CST; spared connections remain, evidenced by persistent high-threshold transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)-evoked responses (Edwards et al., 2013; Perez and Cohen, 2009). A key question for CST repair and rehabilitation is how best to strengthen spared CST connections to improve function.

Current upper limb rehabilitation approaches for corticospinal system injuries depend on the ability to produce arm movements voluntarily, precluding use in patients or animal models with severe weakness or paralysis. Neural activation approaches can overcome this limitation and promote function by relying less on active movement production and more on motor systems stimulation. M1 electrical stimulation intends to promote “top down” voluntary control mediated by the corticospinal system both in animal (Adkins et al., 2006; Carmel et al., 2010; Carmel et al., 2014; Kleim et al., 2003) and human (Conforto et al., 2012; Di Lazzaro et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2005; Nouri and Cramer, 2011) models. After pyramidal tract lesion (PTX), stimulation of the intact M1 in rats promotes spared CST axon sprouting (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007; Carmel et al., 2013; Carmel et al., 2014) and restores voluntary motor function (Carmel et al., 2010; Carmel et al., 2014). Also after PTX, constraining the unimpaired forelimb in rats produces sprouting and behavioral improvement (Maier et al., 2008), suggesting stimulation and behavioral intervention tap into similar mechanisms.

The problem addressed in this study is to develop a translational neuromodulatory strategy in rats to repair the damaged CST and restore forelimb function after injury that ultimately can be used in humans with brain or spinal cord injury. Since M1 and CST are essential for skilled forelimb control, we hypothesized that co-activation of M1 and the spinal targets of the CST would promote plasticity of the motor pathway better than either stimulation alone. And, if so, application of this approach to an injury model would help ensure a better functional outcome. A limitation of present M1 stimulation approaches is that it is prolonged—6 hours/day, for 10 days—resulting in over 106 stimuli (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007; Carmel et al., 2013; Carmel et al., 2014). Such stimulation is too long for practical development of non-invasive therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, long stimulation periods can lead to homeostatic down-regulation of local neuronal excitability, which could affect plasticity (Turrigiano and Nelson, 2004). To overcome this limitation, we use intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS)(Larson et al., 1986). Several minutes of iTBS, implemented using TMS, leads to ~20 minutes of facilitated motor output (Huang et al., 2005). iTBS reduces fast spiking intracortical inhibition in M1 (Benali et al., 2011; Stagg et al., 2009), possibly contributing to plasticity. Because TMS not only activates CST, but also directly activates brain stem pathways in rats (Nielsen et al., 2007), we developed an electrical analog of iTBS using epidural stimulation to activate M1 selectively.

To activate the spinal cord, we use trans-spinal direct current stimulation (tsDCS). tsDCS modulates spinal neuron excitability (Ahmed, 2011; Bolzoni and Jankowska, 2015) and amplifies CST and afferent signals (Ahmed, 2013; Bolzoni and Jankowska, 2015). With a particular electrode configuration, tsDCS can be targeted to the cervical enlargement for forelimb spinal cord neuromodulation (Song et al., 2015). Importantly, cathodal tsDCS (c-tsDCS) augments the M1 forelimb motor map (Song et al., 2015), suggesting that enhancing spinal circuit excitability promotes corticospinal system movement functions.

In intact rats, by using M1 local field potential (LFP) and electromyogram (EMG) recordings, we demonstrate that combined M1-spinal cord stimulation enhanced CST-to-muscle functional connections more than either stimulation alone. Applying the combined neuromodulatory approach in PTX rats, we show robust CST axon sprouting and, importantly, motor recovery. This combined neuromodulatory protocol thus achieves durable enhancement of CST connections and function. Our study demonstrates a clinically-feasible combined M1 and spinal cord therapeutic strategy for motor systems activation to promote function after injury.

Methods

Fifty adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (250~300g) were used for data collection in this study. Six chronically-implanted rats were excluded as they died before completion of the experiment. Table 1 lists the animals used in each experimental condition. We examined the effects of M1 and spinal cord stimulation on CST motor function in intact animals (Table 1; protocols 1, 2, and 3; n=35) and animals that received complete unilateral pyramidal tract lesions (PTX; protocol 4; n=15). For injured animals, 8 rats were chronically implanted with both cortical stimulation and tsDCS electrodes after motor training, and then they received PTX. CST tracing was performed in all of these animals after completion of the behavioral testing; 6 received combined stimulation and 2 served as controls. Data for an additional 7 controls (3 for behavioral testing and 4 for CST tracing) were reanalyzed from our early study, which experienced the identical behavioral training, surgical, and CST tracing procedures as the other animals except without sham tsDCS electrodes (Carmel et al., 2010; Carmel et al., 2014). Then the rats were divided into stimulated or non-stimulated control groups in behavior and tracing tests. The stimulated M1 corresponded to the origin of the intact CST. Care and treatment of the animals conformed to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the City College of New York.

Table 1.

Animals for each group

| Protocol | Animal group | N |

|---|---|---|

| 1&2 iTBS & tsDCS | Anesthetized, acutely prepared | 17 |

| Chronically instrumented (anesthetized/awake) | 9 (9/7) | |

| 3 M1-EMG correlations | Spontaneous locomotion | 9 |

| 4 Pyramidal tract lesion | 15 | |

| Behavior/CST tracing | Injury + stimulation | 6 |

| Behavior/CST tracing | Injury only controls | 2 |

| CST tracing | Injury only controls | 4* |

| Behavior | Injury only controls | 3* |

animals were reanalyzed from our prior study (Carmel et al., 2010)

Stimulation and recording electrodes

We used the same cortical epidural stimulating electrode as in our previous studies (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007; Carmel et al., 2013; Carmel et al., 2014) (Plastics One) and a 12 channel cortical recording electrode array with the reference wire connected to a skull screw. The epidural electrode was used to deliver the phasic stimulation as well as to evoke motor evoked potentials (MEPs) using double pulses (0.2ms duration, interstimulus interval 3 ms). MEPs were used to test corticospinal system excitability, which most likely was mediated by direct activation of the CST. However, there may be additional indirect spinal activation via corticofugal projections to brain stem motor systems. Bipolar EMG electrodes were made with Teflon-coated 7 strand stainless steel. tsDCS electrodes were either modified surface electrodes (StimTent Com; 15 mm by 20 mm; −1.5 to −2 mA; 0.5 mA/mm^2; one pole placed over the C4-T2 vertebrae and the other over the chest) or stainless steel subcutaneous electrode (10 mm by 15 mm) implanted at the same location as the surface electrodes (current: −1.0 mA). We used Finite Element Method (FEM) to simulate that this electrode configuration results in maximal current density within the cervical enlargement (see Supplemental Figure 1; Song et al 2015). The dorsal neck electrode was used as the cathodal electrode. During the awake conditions, the tsDCS surface electrodes were covered by a jacket to ensure stable contact with the skin during behavior. An electrical conductive spray was used to maintain conduction with the skin. Rats were pre-trained to wear the jacket and showed no signs of distress during experiments. tsDCS was delivered using an isolated stimulator (A-M Systems, 2100). tsDCS was applied during M1 phasic stimulation.

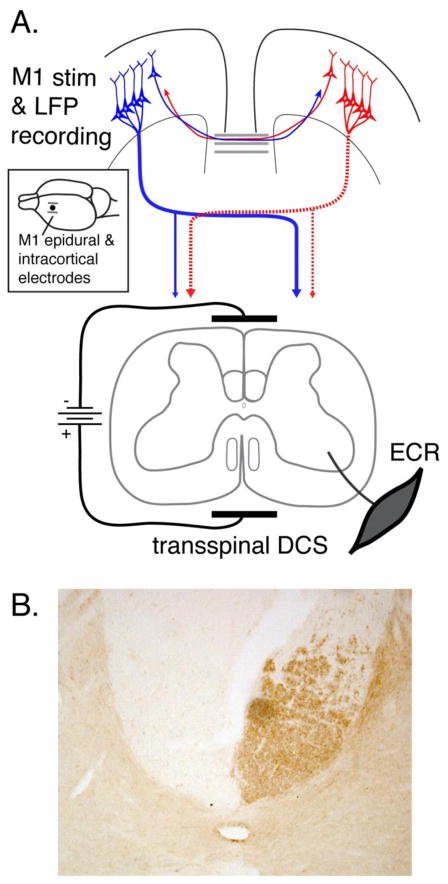

Electrode implantation

For chronic stimulation experiments, animals were anesthetized using the Ketamine (90 mg/Kg) - Xylazine (10 mg/Kg) mixture. Animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame and a craniotomy (4mm by 4mm) was made over the left M1 to expose the forelimb representation. The cortical stimulating electrode was placed over the M1 area epidurally with the two L-shaped electrode wires 2 mm and 4 mm to the midline. The intracortical recording electrodes, which were four tetrodes, each built of 12μm nichrome wires, were inserted between the two stimulation electrodes (1.0 mm anterior from bregma; 2.5 mm mediolateral; 1.0–1.5 mm depth from dura) (Figure 1A). A small opening was made in the dura with a hypodermic needle to facilitate electrode insertion. The position of both the stimulating and the recording electrodes was confirmed by evoked contralateral forelimb movement when passing current via the electrodes (stimulus duration: 45 ms, pulse width: 0.2 ms, intensity: approximately 1.0 mA for epidural and 30uA for the intracortical electrodes). All currents produced only contralateral forelimb responses indicating that our stimulation was selective for forelimb M1, without spread to hind limb M1 or subcortical structures. EMG electrodes were implanted into the extensor carpi radialis (ECR) muscles bilaterally. We focused on ECR because it is a muscle used in skilled distal movements and it is well-represented in motor cortex. After surgery, animals were returned to a holding cage that was set on a heating pad, and observed until ambulatory. An analgesic (Buprenorphine, 0.1mg/Kg) and antibiotic (Ampicillin, 37.5mg/Kg) were administered for two and three days post-surgery, respectively.

Figure 1.

A. Schematic of experimental setup. A bipolar epidural cortical stimulating electrode (see inset) was implanted over the fore limb representation of caudal M1. Recording electrodes (inset; single dot) were implanted between the two stimulating electrodes. tsDCS was delivered through patch electrodes with cathode placed dorsally over the C4 to T1 vertebrae and the anode placed over chest. EMG activity was recorded from the ECR muscle contralaterally. The corticospinal system on the left side of the figure (dotted) highlights that after PTX all CST projections from one hemisphere are eliminated. For the affected contralateral side, the only innervation is the spared ipsilateral CST. B. PKCγ staining marks CST axons in the dorsal column. The micrograph is from a representative PTX animal showing unilateral PKCγ loss due to the lesion.

Neural and EMG recording

Testing started 7 days after surgery when animals were fully recovered. LFPs and EMGs were recorded with a commercial system (CED Power 1401, SPIKE2; Cambridge Electronic Design Ltd.). A unity gain head-stage (Neuralynx) was connected to electrode interface board via flexible cables, and LFPs were amplified (X 1000), band-pass filtered (0.1 – 250 Hz) and digitized at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz. LFPs were further filtered with an offline software notch filter (irrnotch, MATLAB R2012) to remove the line noise. Line noise was removed from EMG activity in real time (60 Hz; Humbug, Quest Scientific) and differentially amplified (X 1000), band-pass filtered (100Hz – 3 KHz) and digitized at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz.

Ladder training and scoring paw placement errors

Rats were trained to walk along a horizontal ladder (Metz and Whishaw, 2002), from one side to the other without stopping, until their forelimb error rate was approximately 10%. Rats were run on the ladder for 10 trials in each direction. Rung positions were changed randomly every five runs to prevent learning a particular pattern. Trials were videotaped by laboratory personnel blind to animal group and scored by a blinded observer. As described previously (Carmel et al., 2010), each step was scored as either good (forepaw palm contacted the ladder rung between the wrist and the digits) or errant (over-step, under-step, or miss). The percentage of errors within a session was used as the behavioral performance outcome measure. Performance was typically accessed twice within 5 days before making the pyramid lesion (baseline) and then every 7 days after injury without additional training in between. The low frequency of testing after injury made it unlikely that the animals derived therapeutic benefit from these sessions.

Pyramidotomy

The pyramid contralateral to the cortex with the epidural stimulating electrode (right pyramid; left M1 electrical stimulation) was transected at the rostral medulla (Carmel et al., 2010). The ventral surface of the occipital bone was exposed at the midline and a small craniotomy was made to access the pyramid tract on the ventral medullary surface. The pyramid on one side was cut with a fine iridectomy scissor to a depth of 1.2 mm below the pial surface immediately adjacent to the basilar artery. To ensure a complete lesion, a 27 gauge needle was passed through the cut. Lesions were verified histologically by transverse sections and cervical spinal PKCγ immunohistochemistry (see Figure 1B).

CST axon tracing and histology

In PTX animals, the CST on the intact side (left M1) was anterogradely traced. At the end of the last session of ladder testing, rats were anaesthetized and placed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments) and body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a heating blanket. The epidural electrode implant was removed to expose the dura over M1, a procedure that does not produce M1 trauma (Carmel et al., 2010). The dura was incised and 7 pressure injections (300nl/each) of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA; 10,000 MW; Molecular Probes; 10% in 0.1M PBS) was made in the forelimb M1 (depth 1.5mm, lateral 2.5 to 3.5mm; rostral: 0.5 to 2.5mm; separated by 0.5mm each injection site). Two weeks later, rats were euthanized by an anesthetic overdose and transcardially perfused (300 ml saline followed by 500ml 4% paraformaldehyde). Tissue containing the lesion site and cervical spinal cord were dissected post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours and transferred to 20% sucrose (overnight at 4°C). Transverse sections of brain stem and spinal cord (around C6) were cut in40 μm thickness. Pyramid lesions were examined using Nissl staining at the site of injury or immunostained the CST below the lesion site with PKCγ to verify loss of CST axons (rabbit anti-PKCγ, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). To visualize BDA-labeled CST axons, sections at C6 spinal segments were incubated in phosphate-buffered (pH 7.4) saline containing 1% avidin–biotin complex reagent (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma), for 2 h at room temperature. After rinsing, sections were incubated with diaminobenzidine (Sigma) for 20 min. After rinsing again, sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air-dried overnight, and cover slipped.

Axon density map and axon length estimation

To monitor changes in ipsilateral (to stimulated/BDA-injected M1 hemisphere) CST axon length from regions of interest within the gray matter, we used an unbiased stereological estimate Stereo Investigator; ‘Spaceball;’ MBF Bioscience Williston Vermont USA), similar to our earlier study (Carmel et al., 2010). Measurements were made by laboratory personnel that were blind to animal group. Briefly, the ipsilateral gray matter border was traced at 20 X magnification under microscope with the above software. The program divided the region into 5 μm by 5 μm squares. Within each measurement square a sampling sphere of 20 um diameter (‘space ball’) was established by the program. Intersections between labeled axons and the sampling sphere were marked under 100 X magnification. An intersection is defined as a contact or crossing of an axon with the cross-section of the sphere, and is saved as a single-pixel dot in an image TIFF file. The number of intersections within each 50 μm square volume was used to estimate local axon length based on sphere volume and tissue thickness (Mouton et al., 2002). TIFF files of individual sections representing intersections as single pixels were then aligned with each other based on tissue orientation and landmarks. The density of marked pixels for each sections were smoothed (2-D low pass filter; filter2, MATLAB R2012) to create a probability heatmap of local axon length after correction for tracer efficacy (see below), as well as the one dimensional projections along dorsoventral and mediolateral axes. Areas without labeling are plotted indigo. Total axon length for each animal was estimated based on the total number of interactions within the gray matter averaged across sections (4/animal). To correct for tracer efficacy, the estimated axon length of each animals (Li) was further adjusted by a correction factor (Ci)

i is the animal number, and Ni is the CST mean axon number across slides for animal i, which was estimated from BDA-labeled axons within the dorsal column opposite to M1 injection side by using the Optical Dissector (Stereo Investigator) under 100X magnification. N is the average axon number across all animals. Finally the adjusted axon length for animal i was calculated as Li/Ci. This stereological sampling and correction allows accurate estimation of axon length, and thus allows to compare how stimulation affects axon outgrowth within the target area. Color-coded maps of corrected regional axon density and axon density p values were constructed using Matlab and registered with the ipsilateral gray matter border.

Experiment design protocols

Four experimental design protocols were used in this study.

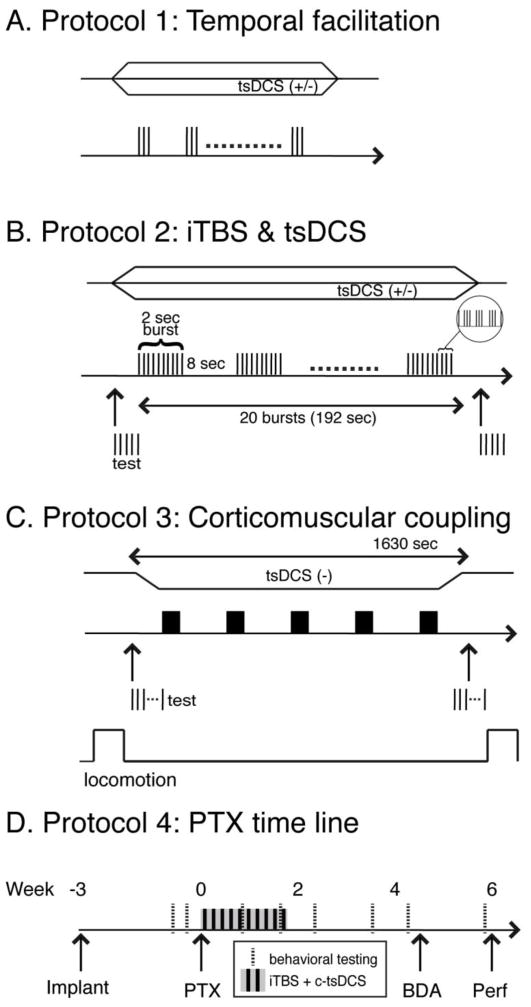

Acute testing of intact animals under anesthesia: Protocols 1 and 2

Protocol 1 was used to determine the optimal inter-stimulus interval (ISI) that would be used for optimizing the timing of pulses within the iTBS and the modulatory effect of tsDCS (cathodal versus anodal). These experiments were conducted in anesthetized rats (see Fig. 2A). A burst of 3 stimuli with different ISIs (3ms, 20ms, 50ms and 100ms) was delivered every 3s through the M1 electrode. Then, by using the optimal ISI (50ms), the DC polarity-dependent effect was tested by c-tsDCS or anodal tsDCS (a-tsDCS) or without tsDCS. MEPs were recorded and their amplitude, area and latency (time from stimulation onset to the first deflection of the evoked potential) were measured and compared under different conditions.

Figure 2.

Experimental protocols. A. Protocol 1 was used to test optimal ISIs for producing facilitation. Cathodal (−) or anodal (+) tsDCS, represented as either the downward or upward directed trapezoids, was applied during the period of phasic M1 stimulation. B. Protocol 2 was used to test the effect of patterned M1 electrical stimulation (iTBS) and the effect of concurrent tsDCS. C. Protocol 3 was used in awake animals during locomotion to test the affect of iTBS, with and without c-tsDCS, on cortico-muscular coupling (R-square value of LFP-EMG relationship). This protocol is similar to Protocol 2 except that 5 epochs of iTBSs (3000 pulses total) were delivered within 1630 second. D. The timeline of protocol 4, which was used to test the effect of the combined stimulation (iTBS/c-tsDCS) on motor recovery and CST ipsilateral sprouting in the PTX subgroup. Stimulation for this protocol is the same used in Protocol 3.

Protocol 2 was used to develop the electrical iTBS (Fig. 2B), based on the parameters optimized in Protocol 1 and to determine the effects of tsDCS. To mimic the protocols used for transcranial magnetic stimulation and to facilitate translation to clinical application, we kept the electrical stimulation parameters similar to those used in magnetic stimulation (Huang et al., 2005). The electrical iTBS consists of delivering a burst of 3 pulses (ISI: 50ms), repeated 10 times, for 2s followed by 8s off; this was repeated 20 times. To summarize pulse number, each burst (as shown in Fig 2B) consisted of 30 pulses. This was repeated 20 times, for a total of 600 pulses. This comprised the basic iTBS stimulation block. The stimulation intensity for iTBS was chosen as 90% of motor threshold level, defined as the intensity inducing a minimal muscle responses (50μV minimal amplitude) in 5 out of 10 testing stimulation trains (2 pulses at 333Hz). We typically observed MEP facilitation during stimulation and, as a consequence, overt muscle responses were often produced by each 3-pulse stimulus burst. The stimulation intensity for MEP evaluation was set at 120% of the threshold established before any modulatory stimulation (iTBS or tsDCS). Since single M1 epidural stimulating pulses did not reliably induce responses, double testing pulses (3ms interval, 200μs duration) were used both before and after the intervention to test MEPs for each session. In some rats we measured limb force produced by stimulation by attaching a force sensor (Grass FT03C; sensitivity range: 2mg – 2 kg) to the forepaw to verify that that a MEP increase was associated with a force increase.

Both Protocol 1 and Protocol 2 were tested under light Ketamine anesthesia (70mg/kg), and in a subset of animals the anesthesia level was monitored by recording the heart rate and verified to be stable. Additional doses (10 mg/kg) were administered if the heart rate increased over 5% of baseline. When multiple testing sessions were conducted in chronically implanted rats, several days were allowed to elapse between sessions.

Awake testing of intact animals: Protocol 3

We used Protocol 3 to test the effect of stimulation on the excitability of the motor output and the functional connection between the cortex and muscle during normal locomotion and quiet resting (see Fig. 2C). Because a single magnetic iTBS session, or continuously delivering iTBS, does not optimally increase excitability or plasticity (Rothkegel et al., 2010; Rothkegel et al., 2009), we used five electrical iTBS epochs as in other studies (Benali et al., 2011). This resulted in a 1630 second stimulation period (~27 min). To determine response facilitation, we compared MEP amplitude after treatment with the pre-treatment amplitude. For this analysis we used average MEP values. The effects of iTBS were examined with or without c-tsDCS. iTBS stimulation intensity was ~90% of threshold. In seven rats, we also measured MEP amplitude before and after the iTBS+c-tsDCS to determine the relationship between Protocol 3 stimulation and motor output during quiet rest.

We used locomotion to test functional connections between forelimb M1 and muscle. During locomotion testing, rats were put in a clean open field (1m by 0.5m) and allowed to freely move within the field for 3 min. To motivate rats to walk continuously, food pellets were scattered within the field. Each session was composed of three periods: pre-stimulation, stimulation, post-stimulation. LFP spectral power was regressed with ECR EMG during the 3 min locomotion epochs before and after iTBS+c-tsDCS. The same handling procedure was used for the control rats, but stimulation was only on for 10s to mimic tsDCS ramping period.

Therapeutic effect of combined stimulation in animals with PTX: Protocol 4

We used protocol 4 to test the therapeutic effect of the combined stimulation (iTBS+c-tsDCS) in PTX rats (Fig 2D). Rats were first implanted with the M1 electrode and then were trained on ladder walking for 2 weeks. When animals reached criterion performance (~10% error rate), they received PTX. Rats receiving treatment underwent the combined stimulation (iTBS+c-tsDCS; as protocol 3) for ten days. The motor threshold in response to M1 stimulation (pulse duration 200us; frequency: 333Hz; train length: 45ms) was assessed immediately before the combined stimulation from the second through tenth session. Motor threshold is defined as the minimum current intensity to produce a contralateral forelimb movement. The ladder score was assessed on the third day after the PTX and then every seven days for one month. The control rats experienced the same procedure except without iTBS+c-tsDCS. After the last ladder testing session, the CST was traced, as described above.

Motor evoked potential analysis

To evaluate the excitability and plasticity of the corticospinal system, we monitored changes in peak-to-peak MEP amplitude (Delvendahl et al., 2012; Sala et al., 2004). As MEPs from the ECR muscle ipsilateral to the side of the stimulating electrode were not reliably induced during M1 stimulation, we only present data from the contralateral ECR muscle. Trials that showed EMG activity during the baseline period (2s before stimuli) were removed from analysis. In a subset of awake animals, we recorded the MEPs when animals remained in a relaxed condition (n=9 animals; Protocol 3).

Regression of LFPs on EMGs during walking

To examine the functional relationship between M1 and muscle, we regressed the M1 LFPs to the contralateral ECR EMG in intact rats during a 3-minute period of overground locomotion (as described above) for the different treatment conditions. M1 LFPs encode both muscle and movement intent during reaching (Flint et al., 2012; Hwang and Andersen, 2013). Compared with single unit activity, LFPs show larger signal and noise correlations across channels (Hwang and Andersen, 2013). Although there is slightly decreased neural decoding performance when using multichannel LFPs than using multichannel spikes, LFPs yield more channel numbers and provides stable long-term recording. Following a similar published procedure (Flint et al., 2013), the functional connection between M1 and ECR was calculated as a multiple linear regression. EMGs were first digitally high-pass filtered at 50 Hz, full-wave rectified, and then low-pass filtered at 10 Hz. Next, LFPs were detrended and line noise removed digitally with a 60Hz notch filter (notch, MATLAB R2012). A non-causal zero-phase digital filter was used by processing the LFP and EMG data in both the forward and reverse directions. Then the power spectra of each channel of LFPs was calculated by using a short-time Fourier transform with a Hamming window (length: 256, step: 20 ms), which results in a power sampling frequency of 50 Hz. Finally, the pre-processed EMGs were down-sampled to the same LFP sampling frequency (50 Hz), and the relation between the above-processed EMGs and the mean spectral power of LFPs within different frequency band was fitted with the multiple linear regression function shown below. Instead of taking the inputs from the mean spectral power of multiple non-overlapping frequency bands for each channel (Flint et al., 2013), we used the mean spectral power of the full frequency band (1 Hz to 250 Hz) of each channel as,

| (1) |

where y is the pre-processed EMG of ECR muscle, and X is the mean spectral power (described above) of LFPs in M1 from the electrode wires. The goodness of fit was estimated by R2 statistics,

| (2) |

where ŷi is the fitted value, yi is the observed value, and ȳ is the average of the observed values. R2 close to 1 indicates a well-fit regression. The correlation coefficient between MEPs during rest and the R-squared values during locomotion was assessed both before and after treatment (iTBS alone, iTBS+c-tsDCS, or control) across each session. The R-squared value is commonly used to evaluate encoding/decoding performance in brain machine interface research and to examine the functional relationship between neural activity (single unit activity or LFP) and behavioral measures (EMG, kinematics and intention) (Flint et al., 2013; Hwang and Andersen, 2013; Song et al., 2009). We tested whether the correlations were significantly different using a bootstrap function (bootstrap, MATLAB R2012).

Statistical analysis

We ascertained differences between protocols with parametric (ttest, MATLAB R2012) and non-parametric tests (ranksum or signrank, MATLAB R2012) for data sets with normal and non-normal distributions, respectively. A two-way analysis of variance was used to test the influence of categorical independent variables (including pulse sequence, ISI, and tsDCS polarity) on MEP changes (ANOVA2, MATLAB R2012), and post-hoc analysis was used for pair comparisons with correction. The significance level was set at 0.05. All data analyses were performed using MATLAB R2012 (MathWorks Inc.).

Results

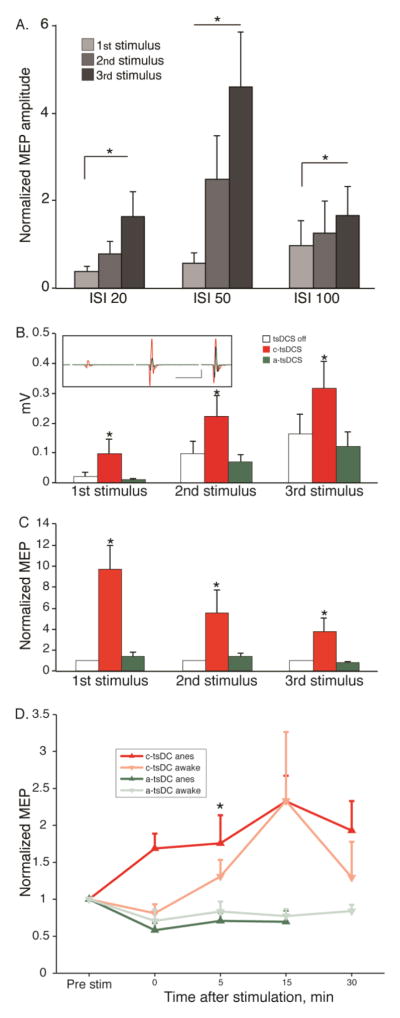

Electrical analog of intermittent TBS augments M1-evoked responses

We first determined the optimal ISI (3ms, 20ms, 50ms and 100ms) for TBS (Fig 3A). Supplemental Figure 2 shows examples of MEPs evoked at the four ISIs. At ISIs greater than 3 ms the MEP was a single biphasic response. The amplitude of the responses were normalized to the shortest interval studied, which corresponds to the frequency used in classical intracortical microstimulation studies (Asanuma and Sakata, 1967). There were significant effects of both stimulation frequency (F(2,2)=4.43, p=0.0137) and pulse sequence (F(2,2)=6.17, p=0.0027), without interaction (F(2,2)=1.66, p=0.163) on MEP amplitude (two-way ANOVA; normalized to the peak amplitude of the first positive and negative responses; i.e., peak-to-peak) evoked by the 3 ms ISI burst. An ISI of 50ms (20Hz) produced the largest overall facilitation, and the response to the third pulse was significantly greater than responses to the first and second pulses (Fig. 3A; p<0.05, signrank). This frequency was used for subsequent phasic stimulation.

Figure 3.

MEP facilitation and effect of tsDCS on MEP facilitation. A. Effect of 3-pulse electrical stimulation of M1 on EMG output (Protocol 1). Average MEP response ± SE to the first, second, and third of the 3 stimuli within the burst at different ISIs. Data are normalized to the response to a 3 ms ISI. The response evoked by the 50ms ISI was significantly larger (measured as the peak-to-peak) than other ISIs (12 sessions from 6 rats; *p<0.05, signrank; error bar: mean + S.E). B. Polarity-dependent effect of tsDCS on the average (+S.E) peak to peak amplitude of evoked MEP (Protocol 2). (*p<0.05, signrank) Inset shows a representative average of the MEP amplitude/waveform without tsDCS (black), with anodal tsDCS (green), and c-tsDCS (red). C. To eliminate the contribution of facilitation due to the multipulse M1 stimulation, each average MEP amplitude was divided by the response without tsDCS. (Data in A and B are from 12 sessions from 6 rats; *p<0.05, signrank; error bar: mean + S.E). D. Aftereffect of c-tsDCS and a-tsDCS. Data are presented for anesthetized (darker lines) and awake animals (lighter lines). (anesthetized: n=9 sessions in 6 rats; awake: n= 6 sessions in 2 rats; signrank, * p<0.05).

Modulation of MEP amplitude during cervical tsDCS

We next determined if the 20 Hz facilitation of M1 stimulation was further augmented by tsDCS. We first determined the group effect with two way ANOVA. There were significant effects of polarity (F(2,2)=6.54; p<0.01) and pulse sequence (F(2,2)=6.97; p<0.01), but there was no significant interaction between these two factors (ANOVA2; F(2,2)=0.29; p>0.05) (Fig 3B). c-tsDCS (Fig 3B, inset; (−); single representative experiment) further increased MEP amplitude to near-threshold M1 stimulation beyond what was produced by simple 3-pulse facilitation (DC off). Post-hoc compassion shows that, across all animals, there was a consistent increase in MEP amplitude during c-tsDCS stimulation than during either DC off or anodal stimulation (signrank, p<0.05, Fig 3B). By contrast, anodal stimulation (DC (+)) had little or no effect (no effect compared to DC off (signrank, p>0.05; Fig 3B).

To identify the component of MEP facilitation specifically related to tsDCS modulation, not to temporal facilitation, we normalized the response to each pulse produced during tsDCS to the same pulse produced in the tsDCS off condition (Fig 3C). After normalization to the tsDCS off condition, the effect was significant for tsDCS polarity (F(2,2)=21.48, p<0.0001), whereas the effect of pulse sequence was close to significant (F(2,2)=2.83, p=0.064) and there was no interaction between the two factors (ANOVA2; F(2,2)=2.27, p>0.05). Interestingly, there was a progressive diminution in facilitation with the second and third pulses. The response amplitudes were not only increased during c-tsDCS, compared with anodal stimulation, but response latency became shorter (Off DC: 11.4 ms ± 0.5 ms; DC(−): 10.6 ms ±0.3 ms; DC (+): 11.9 ms± 0.6 ms; signrank for DC off versus DC(−): p<0.001; signrank for DC off versus DC(+): p<0.05). These results demonstrate in anesthetized rats that during the period when cervical c-tsDCS is being delivered there is a strong augmentation of M1-evoked responses, not just the response to a single stimulus but also the response to a brief train of stimuli. The facilitation with anodal stimulation (Fig 3B) is explained by the temporal facilitation. We also determined that tsDCS facilitates evoked responses after current is turned off (aftereffect; protocol 1; Fig 3D). Similar to reports for single stimuli (Ahmed and Wieraszko, 2012), c-tsDCS produced a positive aftereffect, whereas a-tsDCS produced a negative aftereffect. Furthermore, these magnitude and direction of effects were similar in awake and anesthetized animals (3D).

Sequential M1-evoked MEPs are progressively augmented by iTBS and further enhanced by c-tsDCS

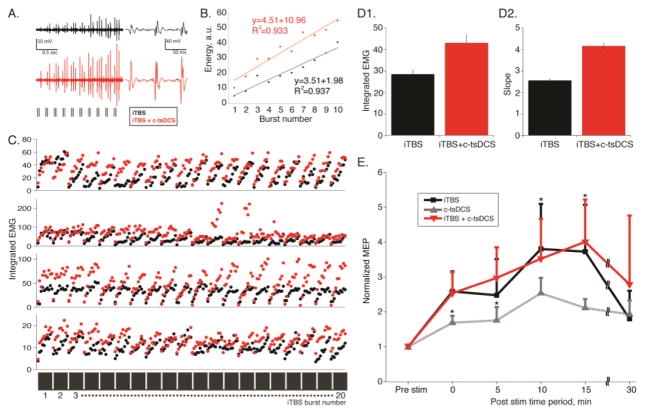

Each 2 second stimulation epoch in iTBS is comprised of 10 high frequency (20Hz) bursts of three stimuli (Fig 2B). Responses evoked by the first few stimulus bursts are smaller than those evoked by the last few bursts (Figure 4A, black). The integrated response to each stimulus burst (Fig 4B, black) shows a progressive increase during the 2 second epoch. Data for the four animals (Fig. 4C; black dots plot integrated EMG to each stimulus burst) revealed similar progressive response facilitation throughout the iTBS block showing that subsequent presentation of the stimuli during the entire 190 sec iTBS period did not show progressive augmentation.

Figure 4.

Facilitation of iTBS is augmented by c-tsDCS (Protocol 2). In this figure black traces, plot lines, and data points are for iTBS only and red, iTBS+c-tsDCS. A. Average of each stimulus presentation during the 2 second iTBS stimulation period (left), aligned with the onset of stimulation. The vertical tic marks below the averages on the left correspond to the triple-pulse stimuli (ISI 50 ms) evoking each set of MEPs. These averages show the changes that occur in MEP amplitude during the 2 second duration of the burst, for the entire period of stimulation (192 sec). The traces to the right are single averages of the 3-pulse stimulation for the entire 192 sec period. B. Scatter plot of MEP integrated rectified EMG response evoked by the 3 stimuli for each burst. We summed the measurements for each stimulus to obtain a combined index of EMG for each triple-pulse stimulus. This graph quantifies the changes in MEP amplitude during the 2 second stimulation period. Linear regression data are indicated in the figure (iTBS only, p<0.001; iTBS+c-tsDCS; p<0.001). C. Amplitude of MEPs to each triple-pulse stimulus during the 192 seconds of iTBS for 4 different rats. The dark gray bars (bottom of part C) represent each 2 second burst (i.e., as in A) and the gaps represent the 8 second interval without stimulation. D. Bar graphs showing changes in MEP rectified and integrated MEP (D1) and the change in slope of linear fit for each 2 second stimulus period shown in part C (D2) (ttest; *p<0.05, ttest). E. Aftereffects of iTBS and modulation by cathodal tsDC under anesthetized condition. Mean change (+S.E) in MEP peak-to-peak amplitude during the 30 minute period following a single epoch of iTBS. Values are relative to MEP amplitude during the pre-stimulation period. (iTBS: n=5 sessions in 4 rats; c-tsDC: n= 9 sessions in 6 rat; iTBS+c-tsDC: n=3 sessions in 3 rats; * p<0.05; signrank).

We next determined that c-tsDCS further augments these responses. The progressively larger responses to the burst sequence are enhanced with c-tsDCS (Fig 4A, B; red). This augmentation was similarly present during the entire iTBS period for the 4 rats examined (Fig 4C). Note in Figs 4B and C that the evoked responses during c-tsDCS were larger overall than with iTBS alone (i.e., iTBS+tsDCS responses (red) are shifted up and to the left compared with iTBS response only (black)). Both the response amplitude (Fig 4D1), and the slope of the regression line, which represents the facilitation speed, (D2)were significantly enhanced with c-tsDCS (ttest, p<0.05). These data show that c-tsDCS further augments the already strong temporal facilitation produce by the patterned M1 stimulation.

We next determined if electrical iTBS produces aftereffects and if c-tsDCS potentiates the aftereffects like it potentiates the direct effects of patterned M1 stimulation. Aftereffects grew during the post-iTBS stimulation period, peaking at about 10–15 minutes (protocol 2; Fig 4E). Compared with iTBS, the positive aftereffect due to c-tsDCS alone was smaller (singrank, p<0.05). Surprisingly, combined (iTBS+c-tsDCS) stimulation did not enhance the iTBS aftereffect (E) (signrank, p>0.05). Although c-tsDCS enhances the direct evoked effect of iTBS, it does not further potentiate the aftereffects produced by iTBS.

Effects of chronic combined tsDCS and iTBS on functional connections from M1 to contralateral muscles

Enhancement of the capacity of the corticospinal system to evoke a response after iTBS, either alone or in combination with c-tsDCS, is consistent with stronger connections between M1 and spinal motor circuits. We hypothesize that if CST connections are stronger, motor-related neuronal activity in M1 should be better correlated with muscle activity. To test this hypothesis, we recorded LFPs in the caudal forelimb M1 and regressed the spectral power of LFPs to rectified EMG activity in the contralateral ECR muscle by multiple linear regression. We sampled LFP and EMG during a 3 minute period of spontaneous, open field, locomotion in animals instrumented for chronic recording.

We conducted multiple experiments in each animal during which either iTBS alone, iTBS+c-tsDCS, or the no stimulation condition was examined. In these experiments in awake animals, we also verified that there were no untoward behavioral effects of either electrical iTBS or cervical tsDCS. Combined M1 and spinal stimulation did not produce seizures or behavioral distress during and after stimulation sessions. Rats remained calm and relaxed or groomed in their cage during stimulation and testing. We computed R-squared values by using a multiple linear regression between recorded LFP activity and recorded EMG activity during a 3 minute period of spontaneous locomotor behavior before and after a 25 minute period of either no stimulation (resting in cage), iTBS alone, or combined iTBS and c-tsDCS. To maximize the potential augmenting effects of iTBS in these experiments, we used a protocol in which iTBS was delivered during 5 sequential periods, each separated by 170 seconds, similar to TMS studies that use multiple sequential epochs (Benali et al., 2011).

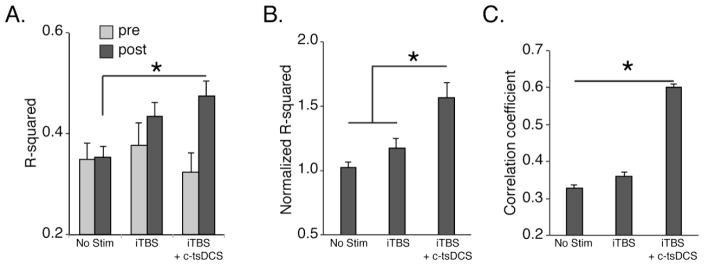

Across the sessions studied, there was a significant correlation between LFP power and EMG during overground locomotion (Fig 5A, open bar; regress, p<0.01). We found no change in the R-squared values across all pre-stimulated sessions (Fig 5A). iTBS alone resulted in an approximately 17% increase in the R-squared values relative to control and a 57% increase when iTBS and c-tsDCS were combined (Fig 5A, B). There was a significantly larger effect after combined stimulation than either iTBS only or control without treatment (Fig 5B; ttest, p<0.05). Our data in behaving animals show that after each iTBS training session corticospinal system connections with spinal motor circuits become more strongly correlated with muscle activity during overground locomotion and the correlation strengthens substantially when iTBS and c-tsDCS are combined.

Figure 5.

Regression of local field potential (LFP) in M1 to EMG in ECR muscle during overground locomotion (Protocol 3). A. Effect of iTBS alone and in combination with c-tsDCS on the computed R-squared value of the regression between LFP and EMG. B. R-squared values normalized to the no stimulation condition. C. Correlation between MEP amplitude and R-squared value for each testing day. The correlation coefficient between MEP and R-squared value changes was significantly different among different conditions (bootstrapping, n=1000 times). (*p<0.05, signrank).

Our experimental paradigm also permitted comparison between stimulation-induced increases in MEPs in awake rats, similar to anesthetized rats (n=9 sessions for each condition in 7 rats in which the animal’s behavioral state was confirmed to be resting quietly). Similar to a recent report that MEP amplitude in humans after iTBS had a large variance across subjects and sessions(Hamada et al., 2013), we also found a large variance in MEP amplitude in awake rats after electrical iTBS; we only observed a significant increase in the combined stimulation compared with controls (ANOVA, F=3.82, p<0.05). To associate the MEP changes with the functional analysis, we determined if the increase in LFP-EMG R-square value is correlated with an increase in MEP amplitude. We calculated the correlation coefficient between the change in MEP amplitude (i.e., post-stimulation divided by pre-stimulation) during rest and during locomotion. For the no stimulation condition, the correlation coefficient was 0.365 and for iTBS alone, 0.440. There was a larger effect with combined stimulation; the correlation coefficient was 0.562. We tested the significance by using a bootstrapping method in which each experimental group (no stimulation, iTBS only, and iTBS+c-tsDCS) was resampled randomly 1000 times (Fig. 5C). We found that the correlation coefficient was the significantly larger for iTBS combined with tsDCS and followed by iTBS only (Fig 5C; ANOVA, F=220.3, p=0.001).

To summarize, forelimb M1 activity is more highly correlated with forelimb EMG after iTBS and that this relationship became stronger when combined with tsDCS. Further, the increases in M1-evoked MEP amplitude were significantly correlated with these increases in functional connections between M1 activity and muscle. This suggests that iTBS combined with c-tsDCS leads to stronger functional connections between M1 and muscle than that of iTBS alone or the non-stimulated control condition.

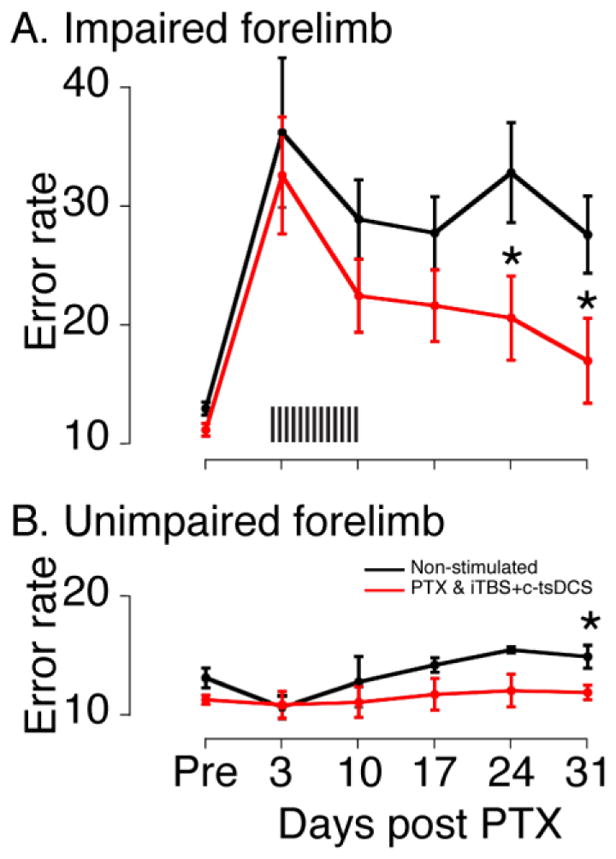

Recovery of skilled movements after combined stimulation in injured rats

We then determined if combined stimulation (iTBS+c-tsDCS) is effective for motor rehabilitation after PTX injury. We examined functional recovery of skilled locomotion in rats that were trained to a criterion error level of 10% before injury for horizontal ladder walking (see Fig 2D for timeline in protocol 4). PTX significantly impaired forelimb performance on the injured side but not the intact side (Fig 6A,B) tested 3 days after PTX, as previously shown (Carmel et al., 2010; Maier et al., 2008). Combined stimulation produced significant improvement in performance by day 24 and by day 31, when error rates were different for the two groups and not significantly different from pre-lesion (Fig 6A; ttest, p<0.05). For the intact forelimb, the ladder score was significantly higher for the control group than the stimulated group at the last session (Fig 6B). Walking speed did not show a significant between-group difference; both showed a similar improvement after 10 days (data not shown). Crossing speed likely reflects an unskilled feature of locomotion, which is not dependent on the motor cortex/CST (Beloozerova and Sirota, 1993).

Figure 6.

Behavioral performance during ladder crossing (Protocol 4). A. Ladder error scores for the impaired forelimb. Unilateral PTX significantly imparied ladder crossing performance of the forelimb contralateral to the lesion, which is ipsilateral to the M1 stimulation electrode. Althougth there was no significant improvement in the ladder score during the ten days of treatment sessions, the combined stimulation significantly improved the performance beginning on day 24 days. B. Ladder error scores of the unimpaired forelimb. No significant differences were found on the unimpared forelimb immediately following the unilateral PTX for both groups (<day 24), although stepping errors were significantly better for the stimulated rats then non-stimulated control rats for the last testing session (day 31). Error bars are mean ± S.E (n=6 for stimulated; n=5 for control). (*p<0.05, ttest).

Electrophysiological changes of combined stimulation in injured rats

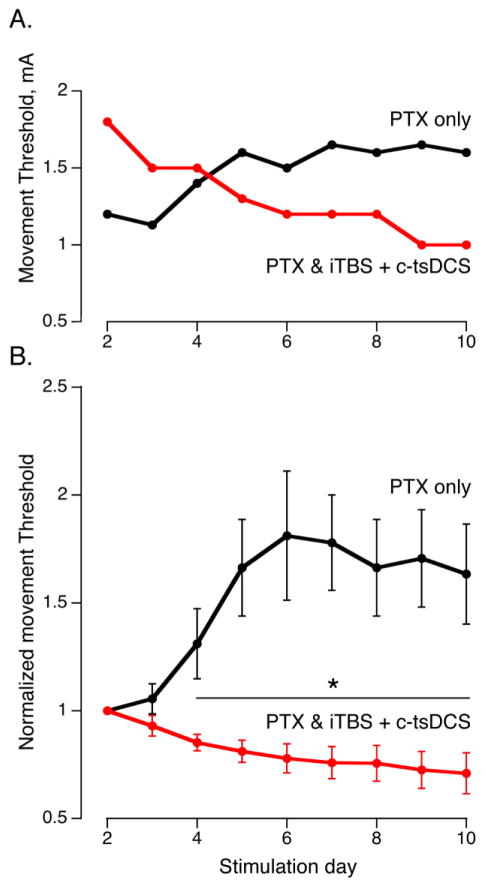

To monitor changes in connection strength associated with therapeutic stimulation, we determined if animals receiving combined stimulation had lower thresholds to evoke limb movement from the stimulated M1 compared with controls. Since ipsilateral forelimb movement is normally produced only at high multiples of the contralateral threshold (greater than 5mA), and not at all after PTX (Brus-Ramer et al., 2009), we monitored the contralateral movement threshold. A representative control animal showed a progressive increase in the normalized movement threshold over the 10 days following PTX, whereas an animal that received combined stimulation showed a decrease during the stimulation period (Fig 7A). After normalization to the movement threshold on day 2 post-injury, there was a clear and significant difference between the two groups beginning on day 4 (Fig 7B). This provides further evidence that the stimulated corticospinal system was strengthened by the combined stimulation and that this early change might underlie the later performance differences between the two groups.

Figure 7.

M1 movement threshold changes after PTX (Protocol 4). A. Movement thresholds (minimal current to produce a movement before each therapeutic stimulation period) for representative stimulated and non-stimulated rats. The movement threshold decreased in the stimulated rat while increase in the non-stimulated control rat. B. Normalized movement thresholds. To correct for variability across animals, the movement threshold was normalizd to the second testing session (evaluation was not made on the first day because of possible residual effects of anesthesia during surgery). The normalized threshold for the stimulated group decreased and increased for the non-stimulated group. There were significant differences beginning on day 4. Error bars are mean ± S.E (n=6 for stimulated; n=3 for control). (*p<0.05, ttest).

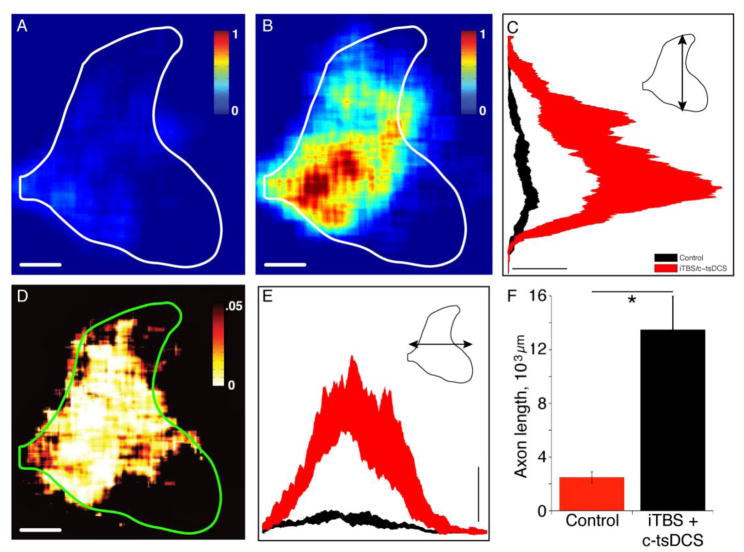

Ipsilateral CST axon changes within the spinal cord after combined stimulation in injured rats

We next determined if combined neuromodulatory stimulation resulted in CST sprouting from the intact side into the denervated ipsilateral gray matter. We estimated the total CST axon length within the spinal cord gray matter on the ipsilateral side in the injury only and injury plus stimulated groups using an unbiased and blinded approach. Averaged color-coded maps of axon length within ROIs show a sparse CST density in the controls and a substantial increase in stimulated animals (Fig. 8A,B). Whereas this outgrowth extends dorsally into the mechanosensory laminae (3–5), the densest outgrowth is within lamina 7, which would be the region with the largest CST denervation with a pyramidal tract lesion and, hence, the most to gain with sprouting (Carmel et al., 2013). The probability map (Fig. 8D) indicates that the medial portions of laminae 3–7 experienced significant increases in CST outgrowth. This demonstrates the high degree of consistency in the topography of outgrowth across animals. Dorsoventral and mediolateral axon length distributions (Fig 8C and E) further show significant differences between groups as evidenced by the lack of overlap of confidence intervals. Overall, there was a 5.4-fold increase in CST axon length in the stimulated over the control group (13,491±1951 μm axon length/40 μm section versus 2490±410 μm axon length/40 μm section; Fig 8F; unpaired t-test, p<0.05). This CST outgrowth likely contributes to motor recovery.

Figure 8.

Ipsilateral CST axon terminal ourgrowth (Protocol 4). A, B. Regional axon density maps plotted using the same color scales from the group mean data for injury only (A) and injury + stimulation (B) show that the combined stimulation promoted axonal outgrowth. Outgrowth was not uniformaly distributed within the ipsilateral gray matter. Calibration: 500 μm. Color scale bars are in arbitrary units and are the same for A and B. C, E. The dorsoventral (C) and mediolateral (E) projections of the 2-D heatmaps. Band represents ± 95% confidence interval. Calibration: 1×10−’4mm axon/pixel. D. Significance map, based on t-statistic values for each pixel. Calibration: 500 μm. F. Total axon length was significantly higher (5.4-fold) in the stimulated group than the non-stimulated control group. Error bars and line are mean ± S.E (n=6 for stimulated; n=6 for control). (*p<0.05, ttest).

Discussion

With neuromodulatory approaches routinely used in human movement studies, we show robust activity-dependent CST sprouting after PTX and significant full recovery of skilled locomotion. We used iTBS, which by itself strongly facilitates MEPs, and further enhanced its capacity to promote CST output with c-tsDCS of the cervical spinal cord. This finding, together with the greater efficacy in potentiating M1-EMG correlations with iTBS + c-tsDCS rather than either one alone, determined our decision to use combined stimulation as a rehabilitation strategy. Importantly, the presence of enhanced correlations between forelimb M1 LFPs and EMG during locomotion provide evidence for stronger functional connections between M1 and spinal motor circuits during motor behavior and increased functional capacity. Combined stimulation of the origin and termination of the corticospinal tract maximally facilitates M1-to-muscle connections in intact rats and promotes CST outgrowth and motor recovery after PTX, suggesting that this neuromodulation approach may be effective clinically for functional rehabilitation after stroke or spinal cord injury.

Electrical analog of transcranial magnetic iTBS

iTBS shows promise for clinical application (Hsu et al., 2013). TMS studies in rodents have been essential for elucidating mechanism (Benali et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). However, since we studied CST projections and behavior we needed M1 stimulation to be selective for M1; hence electrical iTBS. This stimulation is expected to not only activate spinal circuits directly via the CST but also indirectly via cortical projections to brain stem centers that give rise to spinal pathways. As with magnetic iTBS in human and rat (Benali et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2005; Suppa et al., 2008), we too find strong aftereffects. Importantly, our study is the first to show strong direct effects on the evoked MEPs with each high-frequency stimulus train during the iTBS treatment phase. This facilitation could result from synaptic and non-synaptic effects within the spinal cord (Ardolino et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2007). We propose that combined stimulation increases spinal motor circuit excitability—especially during stimulation, but afterwards as well—and this leads to enhanced M1-EMG correlations and larger MEPs. In turn, this promotes injury-dependent CST outgrowth ipsilaterally (Figure 8), enabling effective ipsilateral CST control (Carmel et al., 2010; Carmel et al., 2014; Maier et al., 2008).

Modulating spinal excitability using tsDCS and the impact on CST plasticity

tsDCS has been used to modulate lumbar spinal circuits to promote function after injury and modulate spinal ascending sensory transmission (Aguilar et al., 2011; Ahmed, 2013). Our tsDCS-only experiments in the cervical spinal cord, many of which were conducted in awake animals, provide further support for the utility of tsDCS to modulate spinal cord activity non-invasively. Whereas the mechanism of action of tsDCS is not well-understood, it is dependent on glutamate release (Ahmed and Wieraszko, 2012) and augmentation of the H-reflex (Song et al., 2015) depends on postsynaptic response enhancement (Bolzoni and Jankowska, 2015). With the electrode configuration used in our study, the actions of spinal stimulation are preferentially localized to the cervical enlargement (see Supplemental Figure 1), based on modeling current flow (Song et al., 2015). At the segmental level, it is not yet known which dorsoventral regions of the spinal cord are activated by tsDCS and the extent to which the differential effects of anodal and cathodal stimulation are due to a reversal in current flow or activation of different neural elements/populations. Although an effect on ascending sensory pathways has been demonstrated (Aguilar et al., 2011), modulating ascending signals with cervical c-tsDCS does not appear to contribute significantly to enhancing M1 output (Song et al., 2015). Furthermore, although our modeling study showed substantially higher current density in the cervical enlargement than the brain, there also is predicted current flow in the caudal brain stem owing to the presence of the foramen magnum and a return current path to the cathode (Song et al., 2015). It is possible that this current path could lead to activation of descending monoamine pathways, which can affect motoneuron function (Heckmann et al., 2005).

The modulatory direct effect of c-tsDCS on evoked MEPs is akin to gain control, whereby cortical signals are made more effective during c-tsDCS. This could contribute to longer term strengthening of CST connections with spinal motor circuits, similar to but more robust than what we have observed with CST stimulation alone (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007). We were surprised that the weak positive aftereffect of c-tsDCS did not interact with the stronger positive aftereffect of iTBS. The presence of robust interactions between the directly-evoked actions of iTBS and c-tsDCS, but no interaction with the aftereffects, suggests a simple tsDCS gain effect.

Combined cortical and segmental activation of corticospinal system enhances functional connectivity

We have shown that electrical iTBS augments MEPs in anesthetized as well as awake animals, similar to iTBS using TMS. Importantly, we found that the augmented MEPs can be further enhanced with c-tsDCS. Whereas a commonly-used and important physiological assay of corticospinal system connection strength, the change of MEP amplitude is a physiological not necessarily a functional measure. MEP amplitude changes may reflect primarily the excitability of CST projections, but this does not necessarily represent a motor control function. It should also be recognized that, because a MEP is a stimulus-evoked response, it is influenced by multiple factors not just output connection strength. Local cortical excitability could reduce the threshold for stimulus-produced network activation. In contrast, a highly-regarded standard for functional/motor behavioral assessments is the correlation between neuronal activity and movement/muscle activity; for example, correlated M1 neuron discharge during a particular motor task or in relation to kinematic or temporal features of movement(Ajemian et al., 2008; Georgopoulos et al., 1982; Song et al., 2009). We used LFP rather than single unit recording because it is well suited to chronic recoding. Chronic single unit recordings across multiple days continues to be a challenge (Oweiss, 2010). Further, since LFPs reflect local synaptic activity and the integration of neighboring spiking activity (Buzsaki et al., 2012), they are well-suited for assessment of behavioral correlations with a population of neurons across long term (Flint et al., 2013).

As neurons in M1, including pyramid tract neurons, modulate their activity with the step cycle during stereotypic and adaptive locomotion (Drew, 1993; Drew et al., 2008; Zelenin et al., 2011), we found correlated activity during the period engaged in locomotion. The correlation increased after a period of 5 epochs of iTBS and increased further after the combined stimulation, providing evidence of enhanced engagement of M1 in performance after neuromodulatory stimulation. And further, there was a significant correlation between evoked MEP amplitude and the enhanced functional connectivity. Our experiments suggest that this strengthening of functional connections reflects the direct effect of tsDCS, not the aftereffect because the magnitude of the aftereffect for iTBS alone and in combination with c-tsDCS was not different. Again, this points to a dominant gain control effect of tsDCS.

Combined stimulation promotes motor function after injury

Similar to our previous cortical M1 epidural stimulation study (Carmel et al., 2010), the new combined stimulation (iTBS + c-tsDCS) showed motor function improvement in pyramidal tract lesion animals and robust CST axon outgrowth within the ipsilateral spinal cord. Remarkably, the same recovery we observed with 6 hours of daily stimulation in our earlier study was achieved in this study with approximately two orders of magnitude fewer stimuli and only 27 minutes of stimulation each day. Intracellular motoneuron recordings during c-tsDCS show enhanced 1a EPSPs (Bolzoni and Jankowska, 2015), suggesting that excitatory synapses on motoneurons are important loci for plasticity. This short daily period of stimulation produced significant CST outgrowth in the intermediate zone where last-order interneurons and motoneuron distal dendrites are located in rodents (Asante and Martin, 2013). We hypothesize that c-tsDCS especially activates motoneurons and this, in turn, leads to stronger CST-evoked responses and anatomical connections.

Daily iTBS + c-tsDCS after injury produced a decrease in the contralateral motor threshold before motor function improvement was observed. This could reflect increased CST outgrowth at this early time point (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007). We were surprised that without therapeutic stimulation, contralateral thresholds became significantly elevated (see Fig. 7). This was a substantial effect, with nearly a doubling in threshold. This implies a regressive change in spared corticospinal system function post injury, which has not heretofore been documented. We also observed a late significant control impairment, which could reflect such a regressive change originating from the spared corticospinal system.

Mechanisms of plasticity with iTBS alone and combined with c-tsDCS

iTBS most likely directly modulates the excitability of the CST (and other corticofugal projections), and not spinal circuits. Although it should be recognized that iTBS produced muscle responses that could lead to activation of proprioceptive afferents and, in turn, activate spinal and supraspinal circuits. iTBS could also modulate local M1 neural activity and connectivity, and this could also promote recovery. We envisage the opposite for c-tsDCS, to activate spinal neurons preferentially and not M1 (Song et al., 2015). Spinal neuronal activation, in turn, would increase the likelihood that descending signals from M1 activate spinal neurons. Combined iTBS and c-tsDCS is not likely to act through timing-dependent plasticity, which is thought to underlie which is thought to underlie spike-timing dependent changes observed between the cortex and cervical spinal cord in the primate (Nishimura et al., 2013). tsDCS generates a persistent electrical field that modulates neuronal excitability. There is no timing inherent in this approach.

We show that local spinal stimulation can be combined with M1 stimulation to promote corticospinal motor function, and motor systems repair and rehabilitation after injury. Combined stimulation uniquely resulted in maximal engagement of M1 neural activity (Fig. 5B) and this, in turn, is uniquely associated with stronger effective M1-to-muscle activation (Fig. 5C). This likely underlies the strong sprouting response that we observed, where injury-dependent sprouting is substantially augmented by activation. Significant outgrowth is located within the intermediate zone where many last-order interneurons are located (Asante and Martin, 2013). Compared with sparse ipsilateral CST projections in uninjured animals, this could provide a robust new path by which M1 control signals can contribute to motoneuron function.

Most injuries are incomplete and spared connections are insufficient to mediate significant function. A challenge is to promote functional incorporation of these spared connections into circuitry for motor control, not just to strengthen their connections. For M1, we know the importance of large-scale population coding of movement parameters (Georgopoulos et al., 1982; Song et al., 2009). When the connections of such populations are trimmed to a small number after injury, basic functional coding may not work effectively. Combined iTBS and c-tsDCS could be implemented both to strengthen corticospinal system connections and enhance M1 neuron engagement during movement, with the outcome of promoting motor function during the moment-to-moment movement control by M1 after injury.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cathodal tsDCS enhanced the facilitatory effects of iTBS of motor cortex on muscle evoked potentials

Combined neuromodulation optimally increased motor cortex engagement during task performance

Combined neuromodulation produced corticospinal tract structural plasticity

Combined neuromodulation produced skilled locomotor recovery after pyramidal tract lesion

Combined neuromodulation protocol has translational potential for CST repair.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefanie Henry for help with tetrode construction, and Drs. Lice Ghilardi and Dylan Edwards for critically reading an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the NIH (JHM: 2R01NS064004), the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (JHM: 261214), and the New York State Spinal Cord Injury Board (JHM: C030172; C030091)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins DL, Campos P, Quach D, Borromeo M, Schallert K, Jones TA. Epidural cortical stimulation enhances motor function after sensorimotor cortical infarcts in rats. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:356–370. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar J, Pulecchi F, Dilena R, Oliviero A, Priori A, Foffani G. Spinal direct current stimulation modulates the activity of gracile nucleus and primary somatosensory cortex in anaesthetized rats. J Physiol. 2011;589:4981–4996. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z. Trans-spinal direct current stimulation modulates motor cortex-induced muscle contraction in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:1414–1424. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01390.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z. Electrophysiological characterization of spino-sciatic and cortico-sciatic associative plasticity: modulation by trans-spinal direct current and effects on recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4935–4946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4930-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Wieraszko A. Trans-spinal direct current enhances corticospinal output and stimulation-evoked release of glutamate analog, D-2,33H-aspartic acid. J Appl Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00967.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajemian R, Green A, Bullock D, Sergio L, Kalaska J, Grossberg S. Assessing the function of motor cortex: single-neuron models of how neural response is modulated by limb biomechanics. Neuron. 2008;58:414–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardolino G, Bossi B, Barbieri S, Priori A. Non-synaptic mechanisms underlie the after-effects of cathodal transcutaneous direct current stimulation of the human brain. J Physiol. 2005;568:653–663. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante CO, Martin JH. Differential joint-specific corticospinal tract projections within the cervical enlargement. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma H, Sakata H. Functional organization of a cortical efferent system examined with focal depth stimulation in cats. J Neurophysiol. 1967;30:35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Beloozerova IN, Sirota MG. The role of the motor cortex in the control of accuracy of locomotor movements in the cat. Journal of Physiology. 1993;461:1–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benali A, Trippe J, Weiler E, Mix A, Petrasch-Parwez E, Girzalsky W, Eysel UT, Erdmann R, Funke K. Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation alters cortical inhibition. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1193–1203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1379-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolzoni F, Jankowska E. Presynaptic and postsynaptic effects of local cathodal DC polarization within the spinal cord in anaesthetized animal preparations. J Physiol. 2015;593:947–966. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Chakrabarty S, Martin JH. Electrical Stimulation of Spared Corticospinal Axons Augments Connections with Ipsilateral Spinal Motor Circuits After Injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13793–13801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Martin JH. Motor cortex bilateral motor representation depends on subcortical and interhemispheric interactions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:6196–6206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5852-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents--EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nrn3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Berol l, Brus-Ramer M, Martin JH. Chronic Electrical Stimulation of the Intact Corticospinal System After Unilateral Injury Restores Skilled Locomotor Control and Promotes Spinal Axon Outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10918–10926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1435-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Kimura H, Berrol LJ, Martin JH. Motor cortex electrical stimulation promotes axon outgrowth to brain stem and spinal targets that control the forelimb impaired by unilateral corticospinal injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel JB, Kimura H, Martin JH. Electrical stimulation of motor cortex in the uninjured hemisphere after chronic unilateral injury promotes recovery of skilled locomotion through ipsilateral control. J Neurosci. 2014;34:462–466. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforto AB, Anjos SM, Saposnik G, Mello EA, Nagaya EM, Santos W, Jr, Ferreiro KN, Melo ES, Reis FI, Scaff M, Cohen LG. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in mild to severe hemiparesis early after stroke: a proof of principle and novel approach to improve motor function. J Neurol. 2012;259:1399–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6364-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvendahl I, Jung NH, Kuhnke NG, Ziemann U, Mall V. Plasticity of motor threshold and motor-evoked potential amplitude--a model of intrinsic and synaptic plasticity in human motor cortex? Brain Stimul. 2012;5:586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Ranieri F, Profice P, Pilato F, Mazzone P, Capone F, Insola A, Oliviero A. Transcranial direct current stimulation effects on the excitability of corticospinal axons of the human cerebral cortex. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:641–643. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T. Motor cortical activity during voluntary gait modifications in the cat. I. Cells related to the forelimbs. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:179–199. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Andujar JE, Lajoie K, Yakovenko S. Cortical mechanisms involved in visuomotor coordination during precision walking. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DJ, Cortes M, Thickbroom GW, Rykman A, Pascual-Leone A, Volpe BT. Preserved corticospinal conduction without voluntary movement after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:765–767. doi: 10.1038/sc.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint RD, Ethier C, Oby ER, Miller LE, Slutzky MW. Local field potentials allow accurate decoding of muscle activity. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:18–24. doi: 10.1152/jn.00832.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint RD, Wright ZA, Scheid MR, Slutzky MW. Long term, stable brain machine interface performance using local field potentials and multiunit spikes. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:056005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/5/056005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP, Kalaska JF, Caminiti R, Massey JT. On the relations between the direction of two-dimensional arm movements and cell discharge in primate motor cortex. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1527–1537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-11-01527.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M, Murase N, Hasan A, Balaratnam M, Rothwell JC. The role of interneuron networks in driving human motor cortical plasticity. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1593–1605. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann CJ, Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ. Persistent inward currents in motoneuron dendrites: implications for motor output. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:135–156. doi: 10.1002/mus.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YF, Huang YZ, Lin YY, Tang CW, Liao KK, Lee PL, Tsai YA, Cheng HL, Cheng H, Chern CM, Lee IH. Intermittent theta burst stimulation over ipsilesional primary motor cortex of subacute ischemic stroke patients: a pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Chen RS, Rothwell JC, Wen HY. The after-effect of human theta burst stimulation is NMDA receptor dependent. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron. 2005;45:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang EJ, Andersen RA. The utility of multichannel local field potentials for brain-machine interfaces. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:046005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/4/046005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Bruneau R, VandenBerg P, MacDonald E, Mulrooney R, Pocock D. Motor cortex stimulation enhances motor recovery and reduces peri-infarct dysfunction following ischemic insult. Neurol Res. 2003;25:789–793. doi: 10.1179/016164103771953862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Wong D, Lynch G. Patterned stimulation at the theta frequency is optimal for the induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1986;368:347–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier IC, Baumann K, Thallmair M, Weinmann O, Scholl J, Schwab ME. Constraint-induced movement therapy in the adult rat after unilateral corticospinal tract injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9386–9403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Whishaw IQ. Cortical and subcortical lesions impair skilled walking in the ladder rung walking test: a new task to evaluate fore- and hindlimb stepping, placing, and coordination. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton PR, Long JM, Lei DL, Howard V, Jucker M, Calhoun ME, Ingram DK. Age and gender effects on microglia and astrocyte numbers in brains of mice. Brain Res. 2002;956:30–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JB, Perez MA, Oudega M, Enriquez-Denton M, Aimonetti JM. Evaluation of transcranial magnetic stimulation for investigating transmission in descending motor tracts in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:805–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Perlmutter SI, Eaton RW, Fetz EE. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity in primate corticospinal connections induced during free behavior. Neuron. 2013;80:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri S, Cramer SC. Anatomy and physiology predict response to motor cortex stimulation after stroke. Neurology. 2011;77:1076–1083. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822e1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oweiss KG. Statistical Signal Processing for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology. Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Cohen LG. The corticospinal system and transcranial magnetic stimulation in stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16:254–269. doi: 10.1310/tsr1604-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkegel H, Sommer M, Paulus W. Breaks during 5Hz rTMS are essential for facilitatory after effects. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkegel H, Sommer M, Rammsayer T, Trenkwalder C, Paulus W. Training effects outweigh effects of single-session conventional rTMS and theta burst stimulation in PD patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009;23:373–381. doi: 10.1177/1545968308322842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala F, Lanteri P, Bricolo A. Motor evoked potential monitoring for spinal cord and brain stem surgery. Advances and technical standards in neurosurgery. 2004;29:133–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0558-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Ramakrishnan A, Udoekwere UI, Giszter SF. Multiple types of movement-related information encoded in hindlimb/trunk cortex in rats and potentially available for brain-machine interface controls. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2009;56:2712–2716. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2026284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Truong DQ, Bikson M, Martin JH. Transspinal direct current stimulation immediately modifies motor cortex sensorimotor maps. Journal of neurophysiology. 2015;113:2801–2811. doi: 10.1152/jn.00784.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg CJ, Wylezinska M, Matthews PM, Johansen-Berg H, Jezzard P, Rothwell JC, Bestmann S. Neurochemical effects of theta burst stimulation as assessed by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2872–2877. doi: 10.1152/jn.91060.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppa A, Ortu E, Zafar N, Deriu F, Paulus W, Berardelli A, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation induces after-effects on contralateral primary motor cortex excitability in humans. J Physiol. 2008;586:4489–4500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Crupi D, Liu J, Stucky A, Cruciata G, Di Rocco A, Friedman E, Quartarone A, Ghilardi MF. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances BDNF-TrkB signaling in both brain and lymphocyte. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11044–11054. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2125-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]