Abstract

Three types of contaminated soil from three geographically different areas were subjected to a constant supply of benzene or benzene/toluene/ethylbenzene/xylenes (BTEX) for a period of 3 months. Different from the soil from Brazil (BRA) and Switzerland (SUI), the Czech Republic (CZE) soil which was previously subjected to intensive in situ bioremediation displayed only negligible changes in community structure. BRA and SUI soil samples showed a clear succession of phylotypes. A rapid response to benzene stress was observed, whereas the response to BTEX pollution was significantly slower. After extended incubation, actinobacterial phylotypes increased in relative abundance, indicating their superior fitness to pollution stress. Commonalities but also differences in the phylotypes were observed. Catabolic gene surveys confirmed the enrichment of actinobacteria by identifying the increase of actinobacterial genes involved in the degradation of pollutants. Proteobacterial phylotypes increased in relative abundance in SUI microcosms after short-term stress with benzene, and catabolic gene surveys indicated enriched metabolic routes. Interestingly, CZE soil, despite staying constant in community structure, showed a change in the catabolic gene structure. This indicates that a highly adapted community, which had to adjust its gene pool to meet novel challenges, has been enriched.

INTRODUCTION

Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and the isomers of xylene (BTEX) are of major concern for human health and are classified as priority pollutants (http://water.epa.gov/scitech/swguidance/standards/criteria/current/index.cfm) (1). It is of utmost importance that these chemicals be prevented from entering the environment. Nevertheless, losses of contaminants during industrial and commercial operations, municipal and industrial waste treatment, oil extraction and derivative production, retail distribution of petroleum products, and inadequate storage and sale are the main sources of BTEX contamination of the environment (2).

Several microorganisms have evolved specialized pathways to use aromatic compounds like BTEX as their sole carbon and energy source (3). The analysis of aromatic degradation by isolates gives a valuable understanding of metabolic pathways, where the key steps are the ring activation and the ring cleavage (4, 5). Some important monoaromatic degradation pathways described are the TOD pathway of Pseudomonas putida F1, where the aromatic ring is activated by a Rieske nonheme iron oxygenase (6), the TOM pathway of Burkholderia cepacia G4, where the aromatic ring is activated by two hydroxylations catalyzed by toluene 2-monooxygenase (7), and the TOL pathway encoded on plasmid pWW0 of P. putida mt2, where the degradation is initiated by the oxidation of the methyl substituent by a xylene monooxygenase (8, 9) (Fig. 1). However, even though a huge set of information has been generated using microorganisms enriched in the laboratory, it is known that they often do not play an important role in in situ biodegradation of pollutants (10, 11).

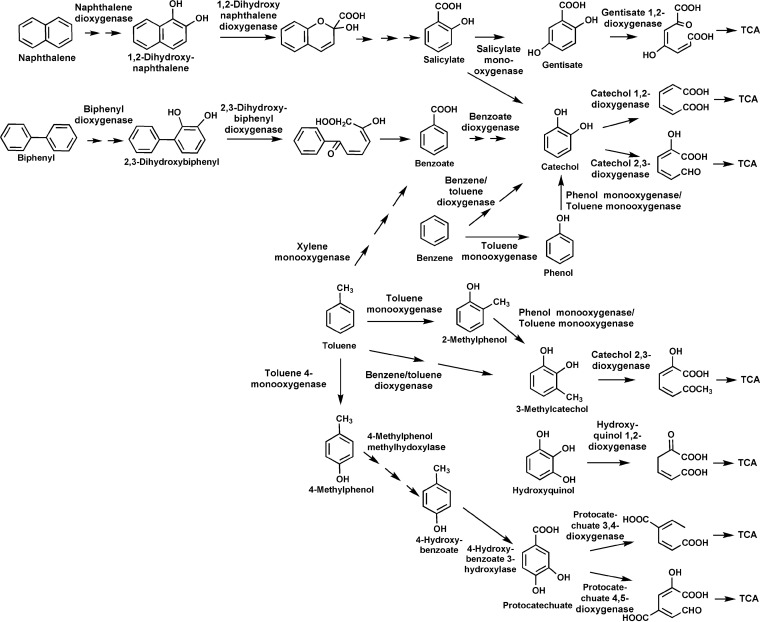

FIG 1.

Major pathways for the aerobic metabolism of toluene, benzene naphthalene, and biphenyl. Activation is usually achieved by Rieske nonheme iron oxygenases typically catalyzing a dioxygenation (27). Rearomatization is then catalyzed by dihydrodiol dehydrogenases (reactions not shown). Alternatively, benzene and toluene can be activated through subsequent monooxygenations catalyzed by soluble diiron monooxygenases (toluene monooxygenase and/or phenol monooxygenase) to form the respective catechols (25). Toluene can be additionally activated through oxidation of the methylsubstituent initiated by xylene monooxygenase or through toluene 4-monooxygenation with 4-methylphenol as an intermediate. Central di- or trihydroxylated intermediates are subject to ring cleavage by intradiol dioxygenases (26) or extradiol dioxygenases of the vicinal chelate superfamily, the LigB superfamily, or the cupin superfamily (25, 26, 69). Ring cleavage products are channelled to the tricarboxylic acid cycle via central reactions.

Studying complex communities and their involvement in bioremediation is challenging and requires multifaceted approaches. Several experimental designs and various techniques have been used for identifying key players in pollutant degradation in the environment or for profiling specific contaminated environments. However, experiments have often focused on isolating the bacteria responsible for degradation after contaminant depletion, usually after short-term incubation (12). Various studies have tried to identify key players in situ using stable isotope probing through the incorporation of labeled atoms into metabolically active microorganisms (13–15); however, community structure analysis has usually been performed with small-scale clone libraries by relatively low-resolution fingerprinting methods. Others studies have focused on the long-term monitoring of contaminated ecosystems in situ through profiling microbial communities and targeting specific catabolic genes assumed to be important (16). As a matter of fact, most research has been focused on describing the degradation rates of pollutants and degrading organisms by the use of clone libraries or fingerprinting methods. Moreover, very little is known about the microbial community response during experimental long-term contamination and pollutant pressure.

Recent studies have characterized microbial communities from contaminated environments using next-generation sequencing (17, 18), and the applicability of the Illumina technology for affordable high-throughput amplicon deep sequencing has been reported (19–21), allowing the identification of key players at contaminated sites (22). Molecular techniques also allow the study of microbial diversity and key catabolic genes in situ. Whereas primer-based approaches typically target only a few groups of genes assumed to be important based on information from cultured organisms (23), functional microarrays targeting a huge set of genes involved in important environmental processes have been reported (24). Recently, a novel catabolic array was described and successfully applied to environmental samples (25). The array is based on upgraded and manually curated databases of key aromatic catabolic genes (26, 27) and thereby avoids massive numbers of misannotations. The array comprises 1,500 probes, and the design facilitates the assignment of positive signals to the respective protein subfamilies, thereby directly inferring function and substrate specificity. Thus, this array is a powerful genomic technology that generates massive amounts of information from single organisms but also from environmental samples, and it solves the limitations of former fingerprinting techniques using primer-based approaches.

The era of next-generation sequencing, in particular via the Illumina platform and microarray technology, has provided us the necessary tools to study the communities as a whole (28). The aim of this work was to analyze microbial community structure and catabolic gene diversity in contaminated soils of different origins under constant and specific long-term contamination with benzene and BTEX in microcosm experiments over time and to identify shifts in community structure and prevalence of key genes for catabolic pathways. To reach this goal, the concentration of the contaminants was considered a fixed parameter instead of a variable during the entire experiment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil samples.

Three different contaminated soil samples were used in this study. The Czech (CZE) soil sample was provided by AECOM CZ s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic, and was derived from a former army airbase at Hradcany, Czech Republic (29). The CZE soil had been under bioremediation treatment and contained residual concentrations of alkanes (C10 to C40; 96 mg/kg), benzene (0.02 mg/kg), toluene/ethylbenzene/xylenes (TEX; 330.6 mg/kg), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs; 0.22 mg/kg). A second soil sample (SUI soil) was provided by Belair Biotech S.A., Geneva, Switzerland. It was collected at a soil treatment station in the city of Geneva, Switzerland, and was heavily contaminated with industrial waste and comprised mainly alkanes (C10 to C40; 9,500 mg/kg) and PAHs (2,300 mg/kg) in addition to minor concentrations of benzene (3.3 mg/kg) and TEX (22 mg/kg). The third soil (BRA soil) was provided by Braskem S.A. (São Paulo, Brazil) and was collected in the south of Brazil at a petrol station, where the ground soil was contaminated with fuel, mainly gasoline. No quantitative data were available for this soil. For more information on soil characteristics, see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Experimental design.

Soil samples (4 g) were deposited in Erlenmeyer flasks (150 ml, total volume), in which benzene or a BTEX mixture was supplied via the vapor phase by evaporation from a glass tube placed through the screw caps closing the Erlenmeyer flasks. Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene isomers were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Steinheim, Germany). The amount of contaminants inside the flasks was kept constant during the entire experiment. To do this, either benzene (26.6 μl) or BTEX (26.6 μl each of benzene, toluene, and ethylbenzene and 8.9 μl of each xylene isomer) was added to the glass tubes in a volume of 500 μl using heptamethylnonane as a solvent. The concentrations of pollutants in the gas phase corresponded to 0.7 mM benzene, 0.2 mM toluene, 0.2 mM total xylenes, and 0.1 mM ethylbenzene relative to authentic standards. Due to evaporation, the glass tubes were exchanged every 4 days. One control microcosm from each soil, for each time point, was incubated under the exact same conditions, without benzene or BTEX treatment.

BTEX components in gas phase were determined by capillary gas chromatography (GC), on a model 6890N GC from Agilent Technologies equipped with an Optima5 capillary column (5% diphenylpolysiloxane-95% dimethylpolysiloxane; length, 50 m; inner diameter, 0.32 mm; film thickness, 0.25 μm). The carrier gas was hydrogen with a flow rate of 70 ml/min. The oven temperature was maintained at 60°C for 1 min, then increased 3°C/min until 80°C was reached, and finally increased 25°C/min until 150°C was reached. A 10-μl gas-tight syringe was used to inject a 2.5-μl volume directly through the GC septum. The injector temperature was set at 220°C, and the detector temperature was set at 300°C (flame ionization detection [FID]).

The microcosms were incubated at 15°C for a period of 90 days, and samples were taken after 2, 4, 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 days of incubation. Original soils were used as time zero controls.

Catabolic gene analysis using microarray.

DNA was extracted, amplified, digested, and labeled, and samples were hybridized and slides were washed as previously described (25). After scanning with a high-resolution microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies, Life Sciences and Chemical Analysis Group, Santa Clara, CA), spots corresponding to the internal control 50-mers A to D were used to generate a standard curve (25), and those samples where a linear curve could not be observed were discarded. Finally, 35 out of 63 microarrays were further analyzed. Signal intensities were normalized against the background using the formula NI = [(probe intensity − background intensity)/background intensity], where NI is the normalized signal intensity, and the average intensity and standard deviation of three experimental replicas were determined. Only probes with a standard deviation of <10% of the average intensity were considered for further analysis. Microarray data, including the sequences of the probes and the intensity recorded, are publicly available in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material.

Community analysis using 16S rRNA gene amplicon preparation.

The community analysis was performed by a modification of a previously described method (21). The V5 and V6 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using primers 807F and 1050R (30) (Table 1) with 1 μl soil DNA as the template in a total volume of 20 μl 5× PrimeSTAR buffer, containing each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 2.5 mM, each primer at a concentration of 0.2 μM, 1 μl of template DNA, and 0.2 μl of PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (2.5 U). An initial denaturation step of 95°C for 3 min was followed by 20 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 51°C for 10 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. One microliter of the first reaction mixture served as the template in a second PCR performed under the same conditions as described above, but for 15 cycles and using the 807F primer containing a 6-nucleotide (nt) error-correcting barcode. Both primers comprised sequences complementary to the Illumina-specific adaptors to the 5′ ends. In a third amplification reaction (10 cycles), 1 μl of the second reaction mixture was used as the template with PCR primers designed to integrate the sequence of the specific Illumina multiplexing sequencing primers and index primers. PCR amplicons were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using 96-well plate purification kits (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, and quantified with the Quant-iT Pico Green double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) reagent and kit (Invitrogen). Libraries were prepared by pooling equimolar ratios of amplicons (200 ng of each sample) derived from each time sample from each soil, all having been tagged with a unique barcode. To remove single nucleotides and concentrate the sample, each library (626 to 1,169 μl in volume) was precipitated on ice for 30 min after the addition of 20 μl of NaCl (3 M) and 3 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol. The precipitated DNA was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was air dried, resuspended in 30 μl of double-distilled water, and separated on a 2% agarose gel. PCR products of the correct size were extracted and recovered using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Negative controls with water as the template were used and were free of any amplification products after all rounds of PCR.

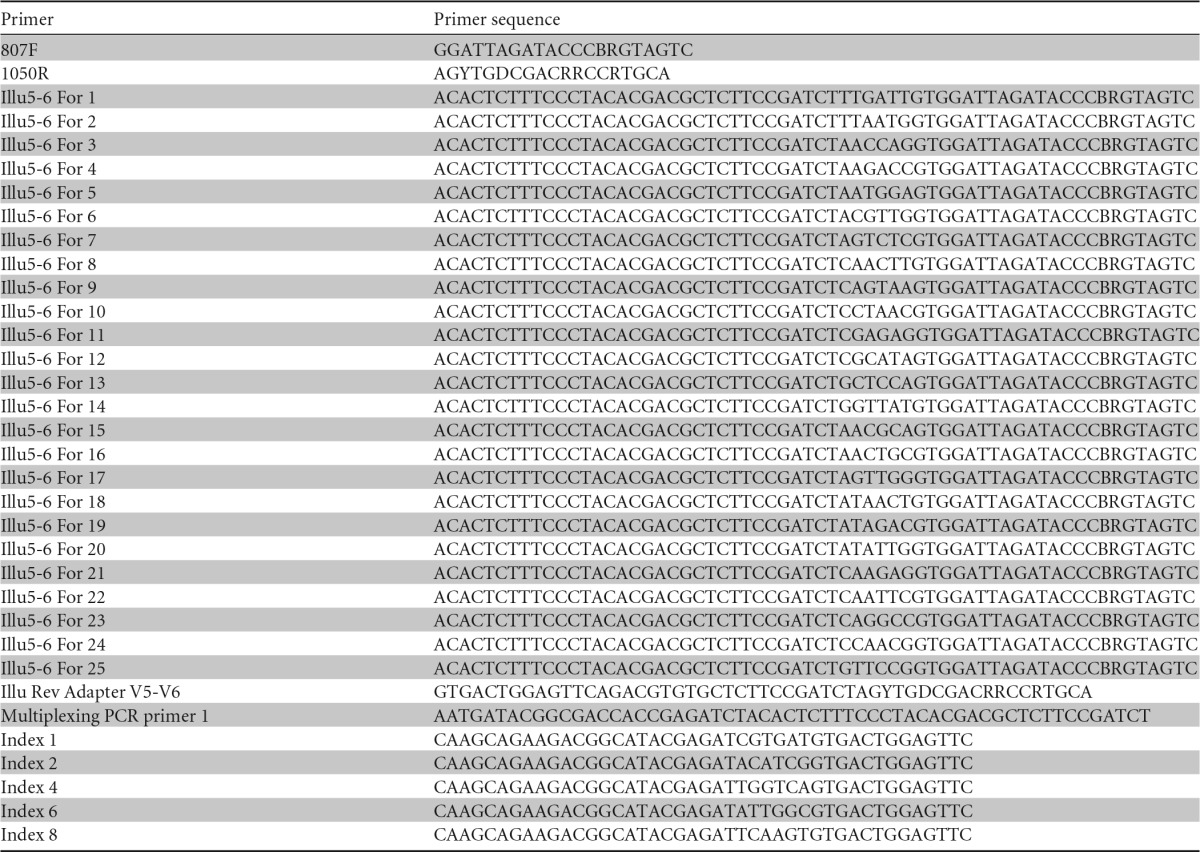

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

Bioinformatic analysis of Illumina data.

For this study, only the forward end sequence reads were processed. In total, 2,003,786 sequence reads were obtained. A quality filter program that runs a sliding window of 10% of the read length over the read and calculates the local average score based on the Illumina quality line of the fasta file trimmed the 3′ ends of the reads that fell below a quality score of 10 (http://wiki.bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/index.php/Trim.pl). Only reads of a minimum of 115 nt in length (29 nt of primer and barcode sequence and 86 nt of 16S rRNA gene sequence) were further analyzed. All truncated reads that had an N character in their sequence, any mismatches within primers and barcodes, or more than 8 homopolymer stretches were discarded. All sequences from each sample were split into different files according to their unique barcode.

A total of 61 samples were further processed, totaling 1,367,917 sequence reads. This data set was collapsed into unique representative reads. These reads were clustered into unique representative reads allowing one mismatch using mothur (31). A representative read was further considered if (i) it was present in at least one sample in a relative abundance of >0.1% of the total sequences of that sample, (ii) it was present in at least 3 samples, or (iii) it was present in a copy number of at least 10 in at least one sample. This reduced the number of representative reads to 486 phylotypes. All phylotypes were assigned a taxonomic affiliation based on naive Bayesian classification (RDP classifier) (32). All 486 phylotypes were then manually analyzed against the RDP database using the Seq Match function as well as against the NCBI database to define the discriminatory power of each sequence read. For read annotation, a species name was assigned to a phylotype when only 16S rRNA gene fragments of previously described isolates of that species showed ≤2 mismatches with the respective representative sequence read. Similarly, a genus name was assigned to a phylotype only when 16S rRNA gene fragments of previously described isolates belonging to that genus and 16S rRNA gene fragments originating from uncultured representatives of that genus showed ≤2 mismatches.

Further analyses were performed in R with the vegan (33) and the phyloseq packages (34). Only samples with more than 7,643 reads (50 samples out of 61) were considered for calculating environmental indices (phylotype richness [S], Pielou's evenness [J′], and Shannon diversity [H′]). Indices were calculated after normalization to the minimum sequencing depth (7,643 reads). A total of 460 phylotypes remained after normalization.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Soil community structure as revealed by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

Three different contaminated soils originating from a former army airbase contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons (CZE soil), a soil contaminated with industrial waste (SUI soil), and a soil contaminated with fuel, mainly gasoline (BRA soil) were analyzed in the current study for their catabolic gene structure and microbial community shifts during long-term contamination with benzene or BTEX. Analysis of the V5 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene indicated the presence of a total of 486 phylotypes, out of which 457 could be identified to the phylum level, 426 to the class level, 374 to the order level, and 336 to the family level.

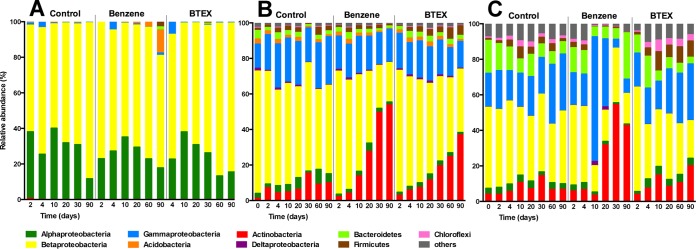

Regarding the class/phylum level composition, the BRA and SUI soils were dominated by members of the Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. Members of these classes were also observed in the CZE soil; however, specifically those of the Gammaproteobacteria were present in lower abundance. The bioremediated CZE soil differed from the other soils by its low diversity (see below), in which members of the Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria accounted for more than 97% of sequence reads (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Microbial community adaptation over time in CZE soil samples (A), BRA soil samples (B), and SUI soil samples (C), treated with benzene and BTEX, and of an untreated control. The relative abundance of sequence reads representing bacterial phyla or classes is given.

Microbial community and catabolic gene shifts upon benzene and BTEX stress in CZE soil.

Analysis of the community based on normalized sequence read data showed a relatively low phylotype richness in the CZE soil which never exceeded 74 phylotypes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Also, the diversity as assessed by the Shannon index (H′) was the lowest of all three soils (H′ < 1.61). The diversity slightly decreased in the untreated soil over the first 30 days (H′30days = 1.35) of incubation but recovered toward the end of the experiment (H′90days = 1.50). Incubation in the presence of benzene or BTEX had only a negligible effect on diversity, and similar to what was observed in untreated soil microcosms, a slight decrease in diversity was observed over the first 30 to 60 days of incubation (see Fig. S1).

Analysis of the community structure over time on the phylotype level also showed only a slight effect of the incubation conditions on the community structure. After 10 days of incubation, an increase of one phylotype (phylotype 108 [Phy108]) indicating the presence of Acidobacteria was observed in the benzene-treated microcosms. After 90 days, this unique phylotype reached roughly 13% of the relative abundance (Fig. 2A).

According to molecular studies, members of the Acidobacteria are among the most abundant bacteria in soil (35) and may represent up to 20% of the total bacteria in soil communities (36). Recent genome sequencing projects targeting bacteria belonging to this group promoted insights into their lifestyle and revealed them to be best suited to low-nutrient conditions (37–39). Holophaga foetida TMBS4T was even capable of degrading several aromatic compounds, such as gallate, phloroglucinol, and pyrogallol, under anaerobic conditions (37, 40), and members of the Acidobacteria have also been identified as abundant in a gasoline spill (41) and even discussed as benzene degraders (15). How far Acidobacteria may be involved in the degradation of pollutants under analysis here remains to be elucidated.

The high stability of the microbial community in the CZE soil was expected, given that it has been under bioremediation for years (29, 42), and consequently the community in this soil should have been adapted to the degradation of aromatic compounds. In agreement, catabolic genes detected on the microarray are related to those observed in proteobacteria (Fig. 3), and signals were observed in the benzene/toluene/isopropylbenzene dioxygenase-encoding genes as well as those encoding enzymes of the EXDO-D branch of catechol 2,3-dioxygenases, as previously described (42–44). In addition, signals of probes indicating the presence of proteobacterial catechol 1,2-dioxygenases and soluble diiron monooxygenases supported the taxonomic results of a community dominated by Proteobacteria.

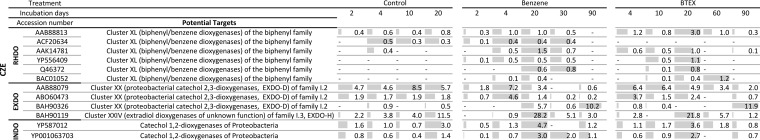

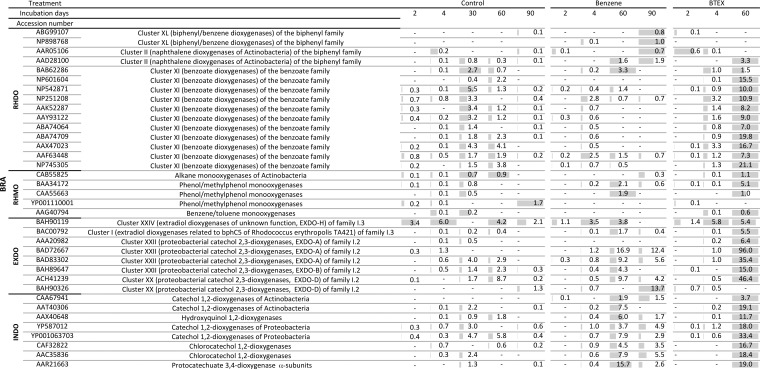

FIG 3.

Microarray hybridization profiles of CZE soil samples. Soils were incubated for 90 days in the presence of benzene or BTEX or without the addition of contaminants (control), and probes showing hybridization in at least one sample of the respective soil are indicated by the accession number of the target gene. Probes were sorted according to the metabolic function of the enzyme encoded by target gene as RHDO (Rieske nonheme iron oxygenase, ring hydroxylating dioxygenase), RHMO (soluble diiron monooxygenases, ring hydroxylating monooxygenase), EXDO (extradiol dioxygenase), or INDO (intradiol dioxygenase). The normalized signal intensities (NI) of probes showing hybridization after the indicated incubation time are given, with a dash indicating the absence of a hybridization signal. Gray bars show the relative intensities, with the highest intensity detected per row being given as a full-length gray bar.

A comparison to the control microcosms incubated without additional pollutant suggests that the BTEX stress results in the selection of genes encoding benzene/toluene/isopropylbenzene dioxygenases related to α-subunits of biphenyl dioxygenases from Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 (WP_011494299.1), Pandoraea pneumenusa B-356 (Q46372), and Comamonas testosteroni TK102 (BAC01052) (Fig. 3) (45). However, after long-term contamination, no signals could be recorded from this subfamily of genes, suggesting that other catabolic genes encoding enzymes capable of aromatic activation, which are not represented on the array, have been selected. Supporting this hypothesis, one probe (BAH90326) encoding a catechol 2,3-dioxygenase related to those of Gamma- and Betaproteobacteria, including extradiol dioxygenase from Cupriavidus sp. strain BIS7 (WP_019451462 ) (46), showed a hybridization signal that was 10-fold the intensity in the microcosm supplemented with benzene and 12-fold the intensity in the microcosms supplemented with BTEX after long-term contamination, compared to the control microcosm. This extradiol dioxygenase-encoding gene in BIS7 is preceded by genes encoding a phenol monooxygenase, which in turn are preceded by genes encoding a toluene monooxygenase in the same operon (WP_019451463 to WP_019451475 ). Since this gene information just recently became available, probes covering the respective monooxygenases were not printed on the array. Thus, even though the taxonomic composition of the soil remained constant, the hybridization pattern suggests an adaptation of the catabolic route responsible for benzene or BTEX degradation. None of the probes targeting genes encoding proteins involved in anaerobic metabolism of aromatics (benzylsuccinate synthases and benzoyl coenzyme A reductases) showed hybridization. This was also true for the experiments using distinct soils described below.

Microbial community and catabolic gene shifts upon benzene and BTEX stress in BRA soil.

Compared to the CZE soil, the BRA soil exhibited a higher phylotype richness, which, independent of the incubation conditions remained constant at S values of 156 ± 18, 159 ± 15, and 163 ± 6 in untreated microcosms and microcosms incubated in the presence of benzene or BTEX, respectively. The diversity of the BRA soil was also higher, as indicated by a Shannon diversity index (H′) roughly double that observed in the CZE soil. No influence of the incubation conditions (H′ = 3.14 ± 0.21, 3.04 ± 0.18, and 3.27 ± 0.14 in untreated microcosms and microcosms incubated in the presence of benzene or BTEX, respectively) was observed. However, in contrast to the absence of an effect of benzene or BTEX treatment on the diversity, the community structure of the BRA soil, as analyzed at the phylotype level, reacted dramatically to incubation with benzene, and a clear increase in the relative abundance of members of the Actinobacteria from 1 to 54% was observed, which correlates with a decrease in the relative abundance from 69 to 22% of those of the Betaproteobacteria, specifically of members of the Comamonadaceae and Hydrogenophilaceae families. A similar trend was observed during BTEX incubation, where actinobacterial phylotypes were also enriched from 1 to 37% and betaproteobacterial phylotypes decreased from 69 to 36% (Fig. 2B).

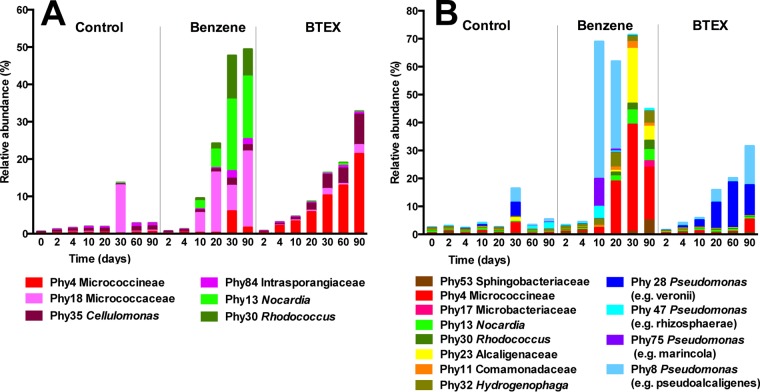

A detailed analysis of phylotypes being enriched (Fig. 4A) during incubation with benzene showed six actinobacterial phylotypes which increased in relative abundance, four belonging to the Micrococcineae suborder and two to the Nocardiaceae family. Phy18, indicative of the presence of bacteria from the Micrococcaceae family, was present in the original soil at a relative abundance as low as 0.006% but increased to a relative abundance of >20% after 90 days of incubation with benzene. Members of the Arthrobacter genus of the Micrococcaceae family have been described to degrade pollutants like methylpyridine (47) and benzene (48). Phy30, indicative of the presence of Rhodococcus spp., present in the original soil even at a relative abundance of 0.003%, increased to a relative abundance of >10% of the total community. Various Rhodococcus strains are well documented for their outstanding abilities to degrade aromatics, among them Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, a versatile biphenyl degrader (49). Phy30 shows a 16S rRNA gene sequence identical to that of R. jostii RHA1. Phy13, indicative of the presence of Nocardia spp., increased in abundance from 0.02% to roughly 19%, and Phy4, which could only be classified as a suborder Micrococcinae bacterium, increased in abundance from 1% to roughly 6% in 30 days and from then on diminished slightly.

FIG 4.

Microbial community adaptation over time of BRA (A) and SUI (B) soil samples. The relative abundances of sequence reads of selected actinobacterial (A) and proteobacterial and actinobacterial (B) phylotypes are given.

Similarly, actinobacterial phylotypes were also enriched in microcosms treated with BTEX. Specifically, Phy4 mentioned above and Phy18, both indicative of the enrichment of organisms of the Micrococcineae suborder, increased constantly in relative abundance from 1 to 21% and from 0.006 to 2.4%, respectively. Phy35, indicative of the presence of a Cellulomonas sp., was also enriched in the benzene microcosm and increased in abundance from 0.4 to 8%. A Cellulomonas sp. has also been previously indicated as capable of degrading aromatic compounds and even biphenyl (50). The enrichment of Actinobacteria during incubation of soil with benzene or BTEX was also reflected in the catabolic gene content (Fig. 5). According to this, probes indicating the presence of genes encoding enzymes related to naphthalene dioxygenase of Rhodococcus sp. strain NCIMB 12038 (AAD28100) (51) and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (BAC00792) of the dibenzofuran degrader Rhodococcus sp. strain YK2 (52) showed enrichment in both types of microcosms, those supplemented with benzene and those supplemented with BTEX.

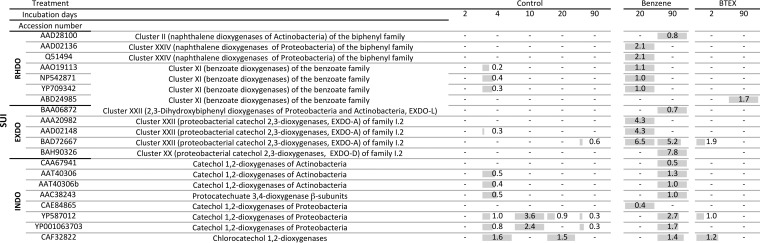

FIG 5.

Microarray hybridization profiles of BRA soil samples. Soils were incubated for 90 days in the presence of benzene or BTEX or without the addition of contaminants (control), and probes showing hybridization in at least one sample of the respective soil are indicated by the accession number of the target gene. The normalized signal intensities (NI) of probes showing hybridization after the indicated incubation time are given, with a dash indicating the absence of a hybridization signal. Gray bars show the relative intensities, with the highest intensity detected per row being given as a full-length gray bar.

Moreover, during extended incubation with benzene, genes encoding actinobacterial biphenyl or isopropylbenzene dioxygenases, related to R. jostii RHA1 (WP_011599002.1 ) and Rhodococcus erythropolis BD2 (NP898768), were highly enriched, suggesting that additional dioxygenases were recruited to attack benzene. Furthermore, various catabolic gene probes indicating the presence of central metabolic routes of actinobacteria showed increased levels of hybridization in microcosms supplemented with benzene or BTEX. For instance, two probes (CAA67941 and AAT40306) indicating the enrichment of genes encoding catechol 1,2-dioxygenases related to those of Rhodococcus opacus 1CP and R. erythropolis SK121, respectively, showed increased hybridization, as well as probe NP601604, indicating the enrichment of genes encoding benzoate dioxygenases related to the enzyme of Corynebacterium glutamicum (53), probe AAX40648, indicating the enrichment of genes encoding hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenases related to the enzyme of Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6 (54), and probe ABA61848, indicating the enrichment of genes encoding maleylacetate reductases related to the enzyme of Pimelobacter simplex strain 3E (55).

Microbial community and catabolic gene shifts upon benzene and BTEX stress in SUI soil.

Overall, the SUI soil showed the highest phylotype richness (S = 283 ± 11) and diversity (H′ = 3.72 ± 0.28) in untreated control microcosms. However, drastic decreases in phylotype richness (S10days = 184), phylotype diversity (H′10days = 2.73), and phylotype evenness (J′10days = 0.46) were observed in microcosms incubated with benzene (see Fig. S1). Both diversity and evenness increased again during extended incubation conditions (H′90days = 3.74; J′90days = 0.65), whereas phylotype richness still declined (S90days = 154).

The overall changes at the phylum/class level (Fig. 2C) in SUI soil over time are as rapid as the reactions observed in the BRA microcosms. However, in contrast to benzene-treated BRA soil microcosms, there was an extensive increase in the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in SUI soil from 18 to 70% during the first 10 days of the experiment. Subsequently, similarly to what was observed in the BRA microcosms, actinobacterial phylotypes increased from 6 to 54% in the first 30 days, whereas betaproteobacterial phylotypes decreased from 45 to 17%.

In the benzene-treated microcosms, an interesting succession of phylotypes were observed (Fig. 4B). Phylotypes indicating the presence of Pseudomonas spp. were enriched during the first days of incubation and reached more than 70% of the total abundance in 10 days. This enrichment in Pseudomonas phylotypes correlated with the decreases in species richness, diversity, and evenness described above. Phy8, indicating the presence of Pseudomonas strains related to Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, was the most abundant phylotype and accounted for 49 and 32% of sequence reads after 10 and 20 days of treatment, respectively. Members of the Pseudomonas genus are in fact widespread in BTEX-contaminated sites (43, 44), and different BTEX metabolic pathways have been previously described (9, 56, 57).

Although the overall relative abundance of betaproteobacterial phylotypes decreased from 45 to 17% in benzene-treated microcosms, a detailed analysis showed that 3 phylotypes were enriched during incubation with benzene (Fig. 4B). These phylotypes indicate the presence of members of the Alcaligenaceae (Phy23), and Comamonadaceae (Phy11 and Phy32) families. Members of these families have previously been described as degraders of pollutants such as naphthalene, biphenyl, and chlorobenzene or even as key players in degradation at contaminated sites (5, 58, 59). As examples, Hydrogenophaga, a genus of the Comamonadaceae family, was identified by stable isotope probing as one of the phylotypes assimilating carbon from benzene in a contaminated site (13), and Achromobacter of the Alcaligenaceae family was identified as a predominant biphenyl mineralizer (60).

After 10 to 20 days, actinobacterial phylotypes started to increase in relative abundance. Even though some of those phylotypes were shared between BRA and SUI soils, such as Phy30 and Phy13 indicating the presence of Rhodococcus and Nocardia spp., respectively, the soil communities being enriched were clearly different. The most abundant actinobacterial phylotype (Phy4), which was also enriched in BRA microcosms treated with BTEX, belongs to the Micrococcineae suborder. It increased more than 100 times in 30 days (from 0.3% to 38%). Other phylotypes increasing in relative abundance also belong to the Micrococcineae suborder but could be classified as belonging to the Microbacteriaceae family and together comprise >15% of relative abundance after 90 days of incubation with benzene.

Compared to the response to benzene treatment, the response of the SUI soil community to BTEX stress seems to be slower. Phy8, indicating the presence of microorganisms related to P. pseudoalcaligenes, increased in abundance over time in the BTEX-treated microcosms and after extended incubation for 90 days accounted for 14% of the community. The same phylotype increased in relative abundance after 10 days in the microcosm incubated with benzene. A distinct phylotype (Phy28) indicating the presence of members of the Pseudomonas fluorescens group was observed to increase exclusively during BTEX treatment. These organisms increased in relative abundance from <0.1% to 16% in 60 days and thereafter started to decline. Interestingly, Pseudomonas veronii strains belonging to this group were previously described as abundant in a BTEX-contaminated area (11). Actinobacterial phylotypes started to increase only after extended incubation.

Analysis of the catabolic gene landscape also indicated that Pseudomonas strains became abundant after 10 days of incubation with benzene, as evidenced by the high abundance of signals indicating the presence of genes encoding proteins similar to catechol 1,2-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10 (CAE84865) or benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain S-47 (AAO19113) (Fig. 6). Concomitant with the obvious enrichment of Pseudomonas strains, two probes indicating the presence of genes encoding catechol 2,3-dioxygenases with similarity to those of P. stutzeri AN10 (AAD02148) (61) and Pseudomonas sp. strain IC (AAA20982) showed hybridization, as well as probes targeting genes encoding naphthalene dioxygenases related to those of P. stutzeri AN10 (AAD02136) (62) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PaK1 (Q51494), indicating that Pseudomonas strains with the ability of degrading hydrophobic aromatic pollutants had become abundant.

FIG 6.

Microarray hybridization profiles of SUI soil samples. Soils were incubated for 90 days in the presence of benzene or BTEX or without the addition of contaminants (control), and probes showing hybridization in at least one sample of the respective soil are indicated by the accession number of the target gene. The normalized signal intensities (NI) of probes showing hybridization after the indicated incubation time are given, with a dash indicating the absence of a hybridization signal. Gray bars show the relative intensities, with the highest intensity detected per row being given as a full-length gray bar.

Similarly, the enrichment of actinobacterial phylotypes during long-term contamination with benzene is also underlined by the enrichment of actinobacterial catabolic protein-encoding genes, such as genes encoding catechol 1,2-dioxygenases similar to those of Rhodococcus opacus 1CP (CAA67941) (63) or Nocardia sp. H17-1 (AAT40306). However, in addition to such genes that were most probably fortuitously enriched, genes encoding enzymes probably involved in hydrophobic pollutant degradation, such as those encoding enzymes similar to 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase of R. jostii RHA1 (BAA06872) (49) or naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase of Rhodococcus sp. strain NCIMB 12038 (AAD28100) (51) were also enriched during extended incubation with benzene, indicating that Actinobacteria were active in the degradation of added pollutants.

Overall soil microcosm assessment.

The reaction in CZE microcosms is slight compared to the reactions in BRA and SUI microcosms. Due to long-term remediation (29, 42), the community is stable and mainly composed of Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria; however, evidence for an adaptation of the metabolic web to the novel pollutant mixtures could be given. BRA and SUI soil harbored similar bacterial communities, and in both soils, extended incubation resulted in an enrichment of members of the Actinobacteria, which was also reflected in the enrichment of genes supposedly characterizing the core genome but also specific oxygenases dedicated to the metabolism of hydrophobic pollutants.

However, whereas in BRA microcosms, Actinobacteria obviously directly took over the lead in biodegradation, a succession of bacterial communities was clearly observed in SUI microcosms, where gammaproteobacterial phylotypes related to Pseudomonas spp. were initially enriched but, after extended incubation, were replaced by betaproteobacterial and actinobacterial phylotypes. This observation may be at least partially explained by the enrichment of fast-growing proteobacterial strains, followed by the growth of strains best suited for degradation under environmental conditions. Even though different phylotypes were enriched in BRA and SUI microcosms, there were also important similarities in the enriched phylotypes and catabolic genes, probably indicative of their environmental fitness.

Clearly different responses of the soil communities to the stress exerted by incubation with benzene and BTEX were observed. This may reflect, on the one hand, their different toxicities. It is well documented that hydrophobic compounds dissolve in the cell membrane and disturb its integrity, with hydrophobicity of a compound being a good indicator of toxicity (64). Accordingly, benzene usually exhibits the highest toxicity of the BTEX compounds (65), which can be overcome by Rhodococcus strains (66). On the other hand, different BTEX compounds are degraded by different metabolisms despite similar structures. As an example, initial oxidation of the aromatic side chain, evidenced as an important mechanism for the degradation of toluene (8) and xylenes (9), is not possible for benzene, and activation through successive monooxygenations is obviously the main mechanisms by which o-xylene is degraded (67). Interestingly, the response to benzene stress was generally faster than the response to BTEX stress. If this is due to metabolic interactions (68) or substrate misrouting remains to be elucidated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Agnes Waliczek for technical assistance and Enga Luye (Belair Biotech SA, Switzerland) and Monika Kralova (AECOM CZ s.r.o., Czech Republic) for supply of soil samples, Philip Breugelmans (KU Leuven, Belgium) for soil analysis, and Michael Jarek for support in sequencing.

This work was funded by BACSIN (project no. 211684) from the European Commission to D.H.P. D.L.-M. was supported by a grant from the CNPq-Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico-Brazil (project no. 290020/2008-5).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03482-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keith L, Telliard W. 1979. ES&T special report: priority pollutants: I—a perspective view. Environ Sci Technol 13:416–423. doi: 10.1021/es60152a601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolden AL, Kwiatkowski CF, Colborn T. 2015. New look at BTEX: are ambient levels a problem? Environ Sci Technol 49:5261–5276. doi: 10.1021/es505316f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Pantoja D, Gonzalez B, Pieper DH. 2009. Aerobic degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons, p 800–837. In Timmis KN. (ed), Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandera E, Samiotaki M, Parapouli M, Panayotou G, Koukkou AI. 2015. Comparative proteomic analysis of Arthrobacter phenanthrenivorans Sphe3 on phenanthrene, phthalate and glucose. J Proteomics 113:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagi JM, Sims D, Brettin T, Bruce D, Madsen EL. 2009. The genome of Polaromonas naphthalenivorans strain CJ2, isolated from coal tar-contaminated sediment, reveals physiological and metabolic versatility and evolution through extensive horizontal gene transfer. Environ Microbiol 11:2253–2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson DT, Koch JR, Schuld CL, Kallio RE. 1968. Oxidative degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons by microorganisms. II. Metabolism of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. Biochemistry 7:3795–3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman LM, Wackett LP. 1995. Purification and characterization of toluene 2-monooxygenase from Burkholderia cepacia G4. Biochemistry 34:14066–14076. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greated A, Lambertsen L, Williams PA, Thomas CM. 2002. Complete sequence of the IncP-9 TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 4:856–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey JF, Gibson DT. 1974. Bacterial metabolism of para- and meta-xylene: oxidation of a methyl substituent. J Bacteriol 119:923–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeon CO, Park W, Padmanabhan P, DeRito C, Snape JR, Madsen EL. 2003. Discovery of a bacterium, with distinctive dioxygenase, that is responsible for in situ biodegradation in contaminated sediment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13591–13596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735529100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witzig R, Junca H, Hecht HJ, Pieper DH. 2006. Assessment of toluene/biphenyl dioxygenase gene diversity in benzene-polluted soils: links between benzene biodegradation and genes similar to those encoding isopropylbenzene dioxygenases. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3504–3514. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3504-3514.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahy A, McGenity TJ, Timmis KN, Ball AS. 2006. Heterogeneous aerobic benzene-degrading communities in oxygen-depleted groundwaters. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58:260–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jechalke S, Franchini AG, Bastida F, Bombach P, Rosell M, Seifert J, von Bergen M, Vogt C, Richnow HH. 2013. Analysis of structure, function, and activity of a benzene-degrading microbial community. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 85:14–26. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schurig C, Mueller CW, Hoschen C, Prager A, Kothe E, Beck H, Miltner A, Kastner M. 2015. Methods for visualising active microbial benzene degraders in in situ microcosms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:957–968. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie S, Sun W, Luo C, M CA. 2011. Novel aerobic benzene degrading microorganisms identified in three soils by stable isotope probing. Biodegradation 22:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10532-010-9377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tancsics A, Farkas M, Szoboszlay S, Szabo I, Kukolya J, Vajna B, Kovacs B, Benedek T, Kriszt B. 2013. One-year monitoring of meta-cleavage dioxygenase gene expression and microbial community dynamics reveals the relevance of subfamily I.2.C extradiol dioxygenases in hypoxic, BTEX-contaminated groundwater. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason OU, Hazen TC, Borglin S, Chain PS, Dubinsky EA, Fortney JL, Han J, Holman HY, Hultman J, Lamendella R, Mackelprang R, Malfatti S, Tom LM, Tringe SG, Woyke T, Zhou J, Rubin EM, Jansson JK. 2012. Metagenome, metatranscriptome and single-cell sequencing reveal microbial response to Deepwater Horizon oil spill. ISME J 6:1715–1727. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton NB, Maphosa F, Morillo JA, Abu Al-Soud W, Langenhoff AA, Grotenhuis T, Rijnaarts HH, Smidt H. 2013. Impact of long-term diesel contamination on soil microbial community structure. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:619–630. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02747-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, Gormley N, Gilbert JA, Smith G, Knight R. 2012. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degnan PH, Ochman H. 2012. Illumina-based analysis of microbial community diversity. ISME J 6:183–194. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camarinha-Silva A, Jauregui R, Chaves-Moreno D, Oxley AP, Schaumburg F, Becker K, Wos-Oxley ML, Pieper DH. 2014. Comparing the anterior nare bacterial community of two discrete human populations using Illumina amplicon sequencing. Environ Microbiol 16:2939–2952. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayamani I, Cupples AM. 2015. A comparative study of microbial communities in four soil slurries capable of RDX degradation using Illumina sequencing. Biodegradation 26:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s10532-015-9731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilchez-Vargas R, Junca H, Pieper DH. 2010. Metabolic networks, microbial ecology and ‘omics’ technologies: towards understanding in situ biodegradation processes. Environ Microbiol 12:3089–3104. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stralis-Pavese N, Abell GC, Sessitsch A, Bodrossy L. 2011. Analysis of methanotroph community composition using a pmoA-based microbial diagnostic microarray. Nat Protoc 6:609–624. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vilchez-Vargas R, Geffers R, Suarez-Diez M, Conte I, Waliczek A, Kaser VS, Kralova M, Junca H, Pieper DH. 2013. Analysis of the microbial gene landscape and transcriptome for aromatic pollutants and alkane degradation using a novel internally calibrated microarray system. Environ Microbiol 15:1016–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez-Pantoja D, Donoso R, Junca H, Gonzalez B, Pieper DH. 2009. Phylogenomics of aerobic bacterial degradation of aromatics, p 1356–1397. In Timmis KN. (ed), Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duarte M, Jauregui R, Vilchez-Vargas R, Junca H, Pieper DH. 2014. AromaDeg, a novel database for phylogenomics of aerobic bacterial degradation of aromatics. Database 2014:bau118. doi: 10.1093/database/bau118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeon CO, Madsen EL. 2013. In situ microbial metabolism of aromatic-hydrocarbon environmental pollutants. Curr Opin Biotechnol 24:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machackova J, Wittlingerova Z, Vlk K, Zima J, Linka A. 2008. Comparison of two methods for assessment of in situ jet-fuel remediation efficiency. Water Air Soil Pollut 187:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohorquez LC, Delgado-Serrano L, Lopez G, Osorio-Forero C, Klepac-Ceraj V, Kolter R, Junca H, Baena S, Zambrano MM. 2012. In-depth characterization via complementing culture-independent approaches of the microbial community in an acidic hot spring of the Colombian Andes. Microb Ecol 63:103–115. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9943-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. 2007. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oksanen J, Guillaume-Blanchet F, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O'Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Henry M, Stevens H, Wagner H. 2015. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.3-2. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

- 34.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janssen PH. 2006. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1719–1728. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1719-1728.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naether A, Foesel BU, Naegele V, Wust PK, Weinert J, Bonkowski M, Alt F, Oelmann Y, Polle A, Lohaus G, Gockel S, Hemp A, Kalko EK, Linsenmair KE, Pfeiffer S, Renner S, Schoning I, Weisser WW, Wells K, Fischer M, Overmann J, Friedrich MW. 2012. Environmental factors affect acidobacterial communities below the subgroup level in grassland and forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7398–7406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01325-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson I, Held B, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Lucas S, Tice H, Del Rio TG, Cheng JF, Han C, Tapia R, Goodwin LA, Pitluck S, Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Pagani I, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Pati A, Chen A, Palaniappan K, Land M, Brambilla EM, Rohde M, Spring S, Goker M, Detter JC, Woyke T, Bristow J, Eisen JA, Markowitz V, Hugenholtz P, Klenk HP, Kyrpides NC. 2012. Genome sequence of the homoacetogenic bacterium Holophaga foetida type strain (TMBS4T). Stand Genomic Sci 6:174–184. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2746047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamps BW, Losey NA, Lawson PA, Stevenson BS. 2014. Genome sequence of Thermoanaerobaculum aquaticum MP-01T, the first cultivated member of Acidobacteria subdivision 23, isolated from a hot spring. Genome Announc 2:e00570-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00570-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward NL, Challacombe JF, Janssen PH, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Wu M, Xie G, Haft DH, Sait M, Badger J, Barabote RD, Bradley B, Brettin TS, Brinkac LM, Bruce D, Creasy T, Daugherty SC, Davidsen TM, DeBoy RT, Detter JC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Ganapathy A, Gwinn-Giglio M, Han CS, Khouri H, Kiss H, Kothari SP, Madupu R, Nelson KE, Nelson WC, Paulsen I, Penn K, Ren Q, Rosovitz MJ, Selengut JD, Shrivastava S, Sullivan SA, Tapia R, Thompson LS, Watkins KL, Yang Q, Yu C, Zafar N, Zhou L, Kuske CR. 2009. Three genomes from the phylum Acidobacteria provide insight into the lifestyles of these microorganisms in soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2046–2056. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02294-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liesack W, Bak F, Kreft JU, Stackebrandt E. 1994. Holophaga foetida gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, homoacetogenic bacterium degrading methoxylated aromatic compounds. Arch Microbiol 162:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00264378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feris KP, Hristova K, Gebreyesus B, Mackay D, Scow KM. 2004. A shallow BTEX and MTBE contaminated aquifer supports a diverse microbial community. Microb Ecol 48:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s00248-004-0001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennerova MV, Josefiova J, Brenner V, Pieper DH, Junca H. 2009. Metagenomics reveals diversity and abundance of meta-cleavage pathways in microbial communities from soil highly contaminated with jet fuel under air-sparging bioremediation. Environ Microbiol 11:2216–2227. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stapleton RD, Bright NG, Sayler GS. 2000. Catabolic and genetic diversity of degradative bacteria from fuel-hydrocarbon contaminated aquifers. Microb Ecol 39:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabelitz N, Machackova J, Imfeld G, Brennerova M, Pieper DH, Heipieper HJ, Junca H. 2009. Enhancement of the microbial community biomass and diversity during air sparging bioremediation of a soil highly contaminated with kerosene and BTEX. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82:565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pieper DH. 2005. Aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 67:170–191. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong KW, Thinagaran D, Gan HM, Yin WF, Chan KG. 2012. Whole-genome sequence of Cupriavidus sp. strain BIS7, a heavy-metal-resistant bacterium. J Bacteriol 194:6324. doi: 10.1128/JB.01608-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Loughlin EJ, Sims GK, Traina SJ. 1999. Biodegradation of 2-methyl, 2-ethyl, and 2-hydroxypyridine by an Arthrobacter sp. isolated from subsurface sediment. Biodegradation 10:93–104. doi: 10.1023/A:1008309026751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fahy A, Ball AS, Lethbridge G, McGenity TJ, Timmis KN. 2008. High benzene concentrations can favour Gram-positive bacteria in groundwaters from a contaminated aquifer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65:526–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLeod MP, Warren RL, Hsiao WW, Araki N, Myhre M, Fernandes C, Miyazawa D, Wong W, Lillquist AL, Wang D, Dosanjh M, Hara H, Petrescu A, Morin RD, Yang G, Stott JM, Schein JE, Shin H, Smailus D, Siddiqui AS, Marra MA, Jones SJ, Holt R, Brinkman FS, Miyauchi K, Fukuda M, Davies JE, Mohn WW, Eltis LD. 2006. The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:15582–15587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hernandez BS, Koh SC, Chial M, Focht DD. 1997. Terpene-utilizing isolates and their relevance to enhanced biotransformation of polychlorinated biphenyls in soil. Biodegradation 8:153–158. doi: 10.1023/A:1008255218432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larkin MJ, Allen CCR, Kulakov LA, Lipscomb DA. 1999. Purification and characterization of a novel naphthalene dioxygenase from Rhodococcus sp. strain NCIMB12038. J Bacteriol 181:6200–6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iida T, Mukouzaka Y, Nakamura K, Yamaguchi I, Kudo T. 2002. Isolation and characterization of dibenzofuran-degrading actinomycetes: analysis of multiple extradiol dioxygenase genes in dibenzofuran-degrading Rhodococcus species. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 66:1462–1472. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen XH, Zhou NY, Liu SJ. 2012. Degradation and assimilation of aromatic compounds by Corynebacterium glutamicum: another potential for applications for this bacterium? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nordin K, Unell M, Jansson JK. 2005. Novel 4-chlorophenol degradation gene cluster and degradation route via hydroxyquinol in Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus A6. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:6538–6544. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6538-6544.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golovleva LA, Pertsova RN, Evtushenko LI, Baskunov BP. 1990. Degradation of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid by a Nocardioides simplex culture. Biodegradation 1:263–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00119763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yen KM, Karl MR, Blatt LM, Simon MJ, Winter RB, Fausset PR, Lu HS, Harcourt AA, Chen KK. 1991. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J Bacteriol 173:5315–5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibson DT, Koch JR, Kallio RE. 1968. Oxidative degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons by microorganisms. I. Enzymatic formation of catechol from benzene. Biochemistry 7:2653–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gross R, Guzman CA, Sebaihia M, dos Santos VA, Pieper DH, Koebnik R, Lechner M, Bartels D, Buhrmester J, Choudhuri JV, Ebensen T, Gaigalat L, Herrmann S, Khachane AN, Larisch C, Link S, Linke B, Meyer F, Mormann S, Nakunst D, Ruckert C, Schneiker-Bekel S, Schulze K, Vorholter FJ, Yevsa T, Engle JT, Goldman WE, Puhler A, Gobel UB, Goesmann A, Blocker H, Kaiser O, Martinez-Arias R. 2008. The missing link: Bordetella petrii is endowed with both the metabolic versatility of environmental bacteria and virulence traits of pathogenic Bordetellae. BMC Genomics 9:449. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fukuda K, Hosoyama A, Tsuchikane K, Ohji S, Yamazoe A, Fujita N, Shintani M, Kimbara K. 2014. Complete genome sequence of polychlorinated biphenyl degrader Comamonas testosteroni TK102 (NBRC 109938). Genome Announc 2:e00865-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00865-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sul WJ, Park J, Quensen JF III, Rodrigues JL, Seliger L, Tsoi TV, Zylstra GJ, Tiedje JM. 2009. DNA-stable isotope probing integrated with metagenomics for retrieval of biphenyl dioxygenase genes from polychlorinated biphenyl-contaminated river sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5501–5506. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00121-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cladera AM, Bennasar A, Barcelo M, Lalucat J, Garcia-Valdes E. 2004. Comparative genetic diversity of Pseudomonas stutzeri genomovars, clonal structure, and phylogeny of the species. J Bacteriol 186:5239–5248. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5239-5248.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bosch R, Garcia-Valdes E, Moore ERB. 1999. Genetic characterization and evolutionary implications of a chromosomally encoded naphthalene-degradation upper pathway from Pseudomonas stutzeri AN10. Gene 236:149–157. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eulberg D, Golovleva LA, Schlomann M. 1997. Characterization of catechol catabolic genes from Rhodococcus erythropolis 1CP. J Bacteriol 179:370–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heipieper HJ, Weber FJ, Sikkema J, Keweloh H, de Bont JAM. 1994. Mechanisms of resistance of whole cells to toxic organic solvents. Trends Biotechnol 12:409–415. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duldhardt I, Nijenhuis I, Schauer F, Heipieper HJ. 2007. Anaerobically grown Thauera aromatica, Desulfococcus multivorans, Geobacter sulfurreducens are more sensitive towards organic solvents than aerobic bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 77:705–711. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paje MLF, Neilan BA, Couperwhite I. 1997. A Rhodococcus species that thrives on medium saturated with liquid benzene. Microbiology 143:2975–2981. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cafaro V, Izzo V, Scognamiglio R, Notomista E, Capasso P, Casbarra A, Pucci P, Di Donato A. 2004. Phenol hydroxylase and toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1: interplay between two enzymes. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:2211–2219. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2211-2219.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jung IG, Park CH. 2004. Characteristics of Rhodococcus pyridinovorans PYJ-1 for the biodegradation of benzene, toluene, m-xylene (BTX), and their mixtures. J Biosci Bioeng 97:429–431. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(04)70232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eltis LD, Bolin JT. 1996. Evolutionary relationships among extradiol dioxygenases. J Bacteriol 178:5930–5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.